This chapter describes the checks that should be made on the substructure (for instance, brickwork and joinery work) before starting and how to identify and solve potential problems. It also contains a checklist for planning the work through to the disposing of the waste and explains some setting-out principles common to all covering materials (that is, slates and tiles).

CHECKING THE ROOF

Checking the Roof for Square

All straight roofs (that is, verge-to-verge or verge to abutment) should be checked for square early in the process to avoid problems later on. Here are the checks that you should make and why you should make them.

Rafter Lengths

Rafter lengths should normally be of equal length at both ends of the roof, especially on roofs that have been formed by using modern factory-made trusses. Traditional ‘cut’ roofs rely much more heavily on the skill and accuracy of the person cutting and fixing the timbers, and so even the best examples may be slightly out. Old roofs in particular may be out by quite a way due to the movement and distortion that can occur over the years. In any case, it is always wise to check the rafter lengths for consistency. The price for not doing so may be the necessity to strip back some or all of the battens that you have so carefully fixed in place (and, as an unwelcome side effect, the underlay will be full of holes where the nails have been).

By using a tape measure, note the length of the left-hand rafter from the ridge down to the edge of the fascia board. Alternatively, it is acceptable to fix the first course batten and measure to the top edge of that instead of the fascia board. Repeat the process on the right-hand side and compare the measurements. If the difference is only slight (a few millimetres) you will not need to make any adjustments to the battening gauges and the top course of battens will finish parallel to the ridge, thus ensuring a correct finish when the roof is tiled. However, any significant difference in the measurements will result in the top batten slanting towards or away from the ridge rather than being parallel to it. Apart from the obvious visual problem, this can cause difficulties when it comes to fixing the tiles. Later, in the product-specific chapters, I shall describe exactly how to deal with this situation for each type of tile or slate, but, in general, the difference is split evenly throughout a number of gauges by reducing the gauge slightly on one end. This ensures that the battens can then be fixed in such a way that the gradual adjustment is not visible to the naked eye.

Ridge and Eaves’ Lengths

This applies to straight roofs only. On a straight verge-to-verge roof it is unlikely that the ridge length will be exactly equal to the eaves’ length and it is important to know how much difference there is before we begin to lay any roof tiles. As with the rafter lengths, a few millimetres here or there are not going to make much difference, but, if there is a significant difference, then adjustments to the joinery work may be necessary.

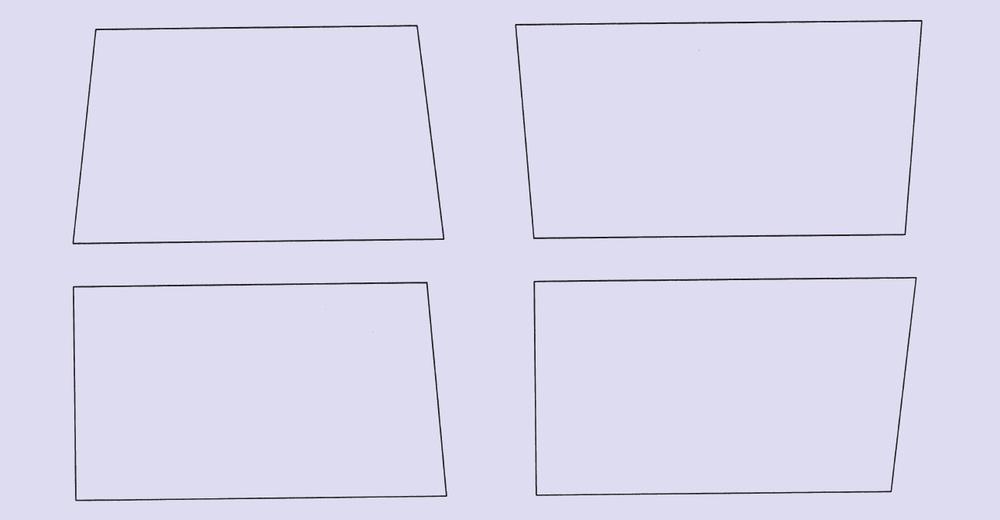

Out of square roofs (exaggerated for clarity).

Out of square roofs – how to ‘run’ the undercloak.

But, before you set about altering the joinery work, it may be possible to fix the problem during the ‘setting/marking out’ process by fixing the undercloak at a slight ‘running’ angle to square the roof back up. For example, if we overhang the undercloak 38mm over at the bottom and 50mm over at the top, we have squared the roof up by 24mm (12mm each side). While ‘running’ the undercloak in/out can come in handy, it should only be used to get you out of a problem; where possible it is better to keep the overhangs equal and open/close or in some cases cut the slates or tiles (see product-specific sections).

Right Angles Check

You would probably think that, if the rafters are the same length and the eaves and ridge are equal, then the roof would be square. Not necessarily, the roof could be shaped like any of the examples in the illustrations above. It is important that the verges (bargeboards) are running at right angles to the eaves (fascia) so that the battens are fixed square and parallel, ready for the slates or tiles. A verge which is not at 90 degrees (running off ) can result in an unsightly twisting of the slates or tiles when laid, sometimes referred to as ‘sore-toothing’. On pediments and valley sections it is the ridge line that needs to be square, rather than the eaves.

Builder’s Square

If you have a builder’s square or any flat, rectangular object that you know has right angles on it, the checking process will take only a few seconds. Simply place the square in the bottom corners of the roof, with one edge on the fascia board and the other in line with the bargeboard and perform a quick visual check for square.

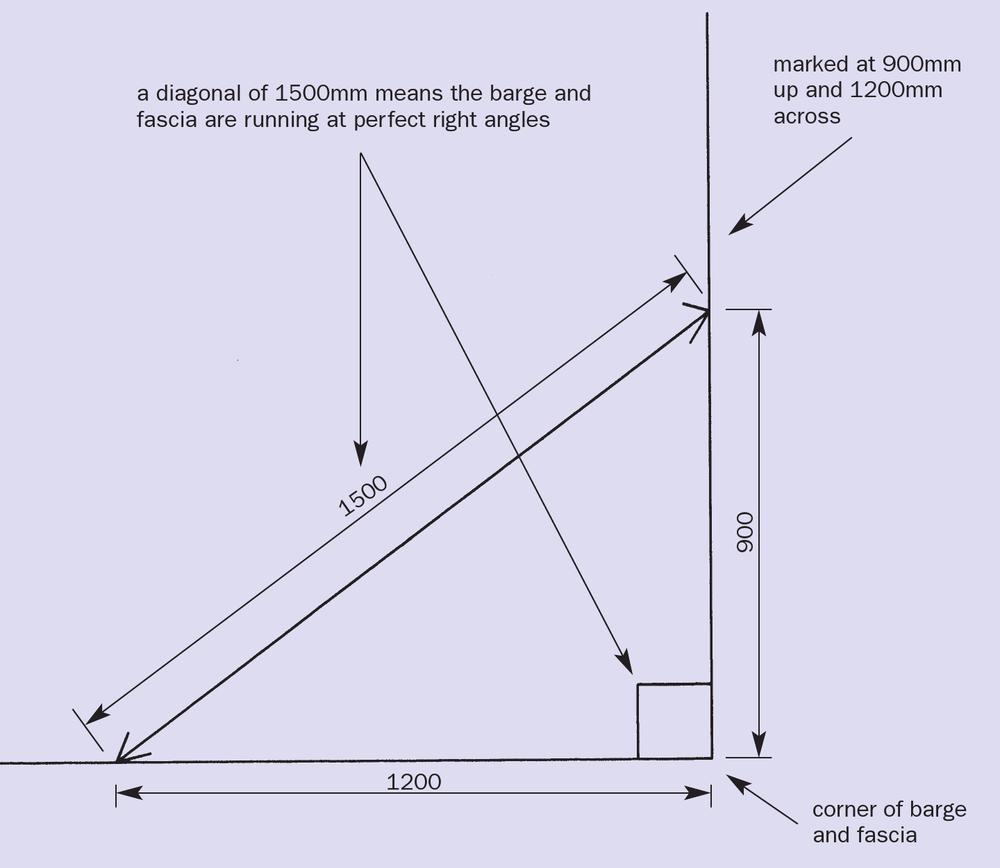

The 3, 4, 5 Method

Another tried and tested way of checking for right angles is to use the 3, 4, 5 method, based on Pythagoras’s theory. I shall avoid going into mathematics because this would just confuse the issue, suffice it to say that this method has long been known and is used in many operations across construction, and this is how we are going apply it.

- Start at the outer corner of the fascia/barge junction and measure back 1200mm along the fascia and mark this point.

- Then measure up the bargeboard 900mm and mark that point.

- Now simply measure between the points and, if the junction is square, the diagonal measurement should be 1500mm.

How to check for square using the 3, 4, 5 method.

This is just an example; you can use any measurements you like as long as they stay in the 3:4:5 ratio. Do not get too concerned if this is slightly out, the tiles or slates will still lay perfectly well provided the junctions are reasonably square. If your checks show that the roof is significantly out of square, you may need to consider correcting this before carrying on. However, depending on the materials being used, there are a few tricks of the trade, which can be used so we shall look at how to deal with out-of-square roofs in the product-specific sections.

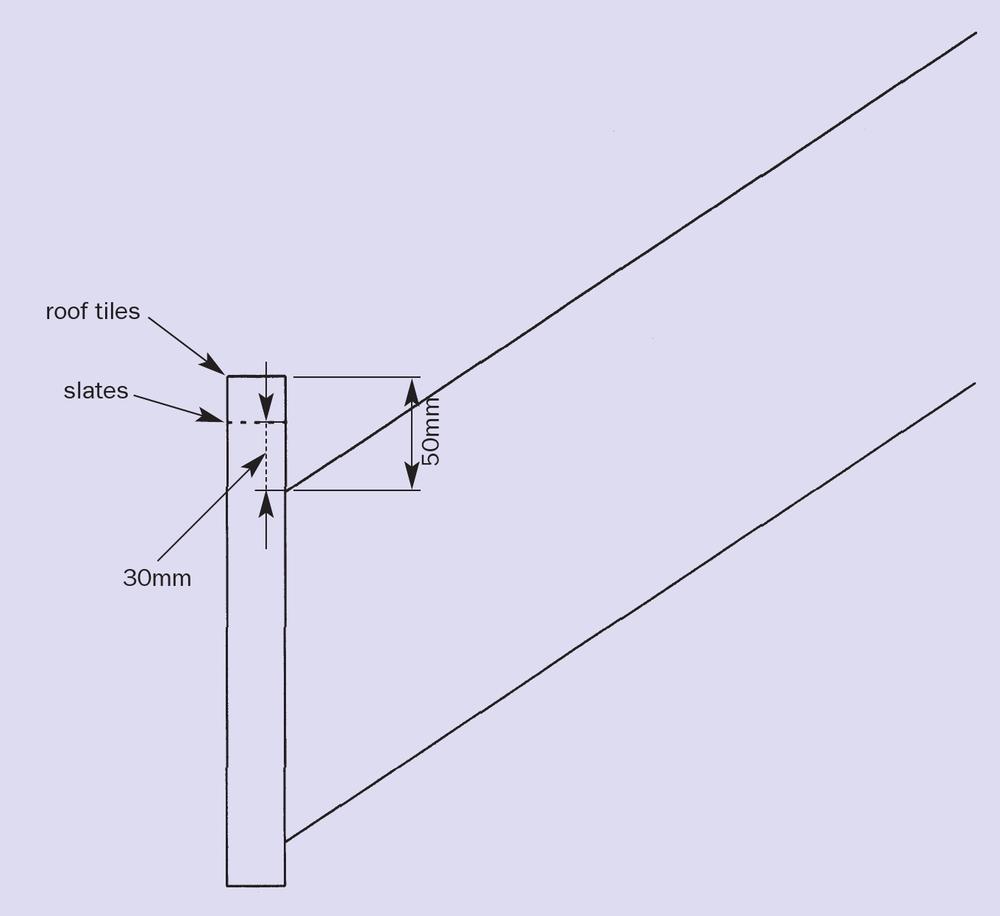

Fascia board heights for different materials.

Fascia and Bargeboard Heights

Fascia Boards

The minimum upstand height at the fascia board (plus any over-fascia ventilation strips, if used) needs to be about 30mm for slates and 50mm for roof tiles. The angle of the slates or tiles on the bottom course should be at least the same as those on the main roof, or there should be a slight upwards tilt at the eaves, often referred to as a kick.

Perhaps the most reliable way to check fascia boards for height is actually to pin (that is, nailed but not fully driven) a couple of short pieces of batten into place and see how the bottom two courses look when laid. If the bottom course drops away, you may need to increase the fascia height. Often the simplest way to do this is to fix a batten to the top edge of the fascia (often called a kick-lath or batten).

If the opposite problem exists and the roof kicks up sharply, the bottom course may end up too flat, which means that water will not run off properly and the area could leak. In this case the fascia may need to be replaced or dropped down to improve the run-off into the gutter. If adjustments are required they should be done place before you fix any permanent battens, because alterations afterwards will affect how much the tiles or slates overhang into the gutter.

Bargeboards

Bargeboards should finish flush (level) with the line of the rafters. This can be easily checked by eye, or by running a straight edge along to check the alignment. A flush finish means that the batten ends will be fully supported and allow any undercloak (if used) to sit at the correct angle. If the bargeboard is below the line of the rafter it will fall away slightly, but this is not necessarily a problem and, in fact, it may actually help to drain water that runs down the verge away from the building. Having the bargeboards too high has the opposite effect and therefore should be avoided.

Although technically incorrect in most circumstances, in some areas it is fairly common practice to set the bargeboards up by 25mm above the end rafter so that the top edge is in line with the battens once they are fixed. This means that the undercloak (if applicable) goes on top of the battens rather than under them. If you encounter this, you will have to take one of the tile nibs off to get the tile to sit properly (right-hand side one for right verge, left-hand for left verge). The alternative, of course, is to have the joinery work corrected.

Brickwork

In most standard forms of construction there will be brickwork or some other masonry at the gable ends and party walls between the properties, if they are terraced or semi-detached. It is important to ensure that none of the brickwork is above the rafter line since this can damage the underlay or interfere with the battens. As with the bargeboards, this can be checked by eye or by running a straight edge down the rafters and over the brickwork.

Planning the Job

Most slating and tiling jobs should follow the same pattern of scaffold erection (by a competent person only), felting (underlay) and battening, setting or marking out, the fixing of any background components (such as undercloak or valley liners), loading out followed by the fixing of the slates or tiles and finally any mortar work or dry fix details. The final part of the process is the tidying up and the safe disposal of any waste.

This may all seem quite straightforward, but it is well worth going through the job in your mind first to ensure that:

- the working platform (scaffold) is erected on time and is fully complete and to your needs;

- a suitable skip is on hire or, if you are tipping the waste, that you have contacted the local authorities to do this in line with the regulations;

- any plant you may require is available and suitable for your needs (such as disc cutters or mixers);

- you avoid foot traffic on the slates or tiles once laid; there are too many possibilities to go into, but typically you should try to avoid tiling or slating the whole roof in and coming back to it, instead, try to complete details such as hips, valleys or ridge as the slates or tiles are brought through as this normally allows you to work off the battens; there will times when this might not be practicable or possible and in this case you should use a roofer ladder.

Materials Check

This again is a fairly obvious thing to do, but I have seen many jobs delayed and working hours lost because the materials were not checked first. It is a simple matter of checking the materials delivered against the list that you need to do the work. I recommend something along the lines of:

- roof tiles (or slates): check quantity and colour or finish and breakages (if possible);

- fittings (ridge tiles, verge tiles, for instance): as above;

- battens: check size and quantities;

- underlay (felt): check number of rolls and for any damage;

- mortar materials (if used): check that cement has no hard lumps, availability of a clean water supply and plasticizer and check ratio of sand to cement (3:1);

- dry fix and ventilation components: check that there are instructions, fixing kits (screws, clips, for instance) and enough of each component, including any stop ends and end capping pieces, for example;

- fixings: check that the nails and clips, for example, are correct for the materials you are using and are sufficient in quantity;

- lead (if used): check that the code is correct and for size and quantities (see chapter 10 on basic flashings).