Poets Theater Two Versions of Collateral

RAISING COLLATERAL KIT ROBINSON

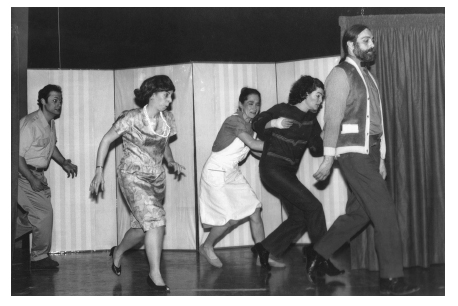

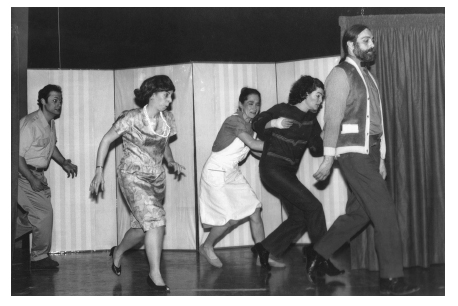

San Francisco Poets Theater, founded in 1979, was preceded by several prior incarnations. In the early 1950s, Frank O’Hara and his friends wrote and produced plays as Poets’ Theater in Cambridge, Mass.; poets of Jack Spicer’s circle did likewise in San Francisco; and the Judson Church Poets Theater flourished in New York in the 1960s. The following essays from Poetics Journal’s symposium on Poets Theater (1985) focus on Kit Robinson’s Collateral, directed by Eileen Corder (1982), as representative of the compositional methods and performance values of San Francisco Poets Theater.1 Borrowing from many sources (Bertolt Brecht, Vsevolod Meyerhold, El Teatro Campesino, improvisatory techniques, and New York School and Language School poetries), its productions were always highly conceptual and often hilariously funny. Central to its methods was the construction of illusionistic sequences from the interpretation, through improvisation, of abstract, elliptical, nonnarrative scripts. In the resulting performances, fragments of language strike poses and acquire agency even as persona and voice become arbitrary. Poets Theater has been a creative resource for the writing of Steve Benson, Charles Bernstein, cris cheek, Carla Harryman, Kevin Killian, C. S. Giscombe, Leslie Scalapino, Rodrigo Toscano, and Edwin Torres, and it continues to thrive with the development of work by younger writers. An anthology of writing for Poets Theater, edited by Killian and David Brazil, was published in 2009.

In writing the play Collateral, I had the advantage of knowing not only that it would be produced, but that it would be produced by a group willing to take on any challenge to the director and actors I might care to throw their way. I had license to write a problematic work.

Scouring a notebook, I lifted lines for a play, to be built up from particular instants, realized in writing, toward a whole to be realized on stage. So the themes were derived, not from a sole idea or plot, but directly from disparate, daily experience. And I tried to shape the materials to give them dramatic form—scenes, characters, conflict, resolution, fast and slow pacing, cumulative emotional pressure and release. I imagine this is the inverse of the way plays are normally written.

To develop characters, I looked for distinct tones in the writing and assigned each a name. The first two character types to emerge this way were Bell and Lopez. Bell’s tone is sharp, exuberant, and extravagant. In scene 1, he personifies the revolutionary Russian Futurist Velimir Khlebnikov. While taking shots at conventional wisdom (“What’s clear and distinct to you and me may look like smog to an Aleutian”), he seems to suggest that literally anything is possible and that he’s the man whose say-so makes it so. If he’s living way beyond his means—heavily in debt to language for the reality he so elastically delineates—he grounds his confidence in the dramatic artifice (“For collateral take stages left and right”). Bell’s sidekick and foil, Lopez, speaks with a slightly sour, fatalistic tone. I imagine him as a cynical old warrior, someone who’s “seen it all.” His skepticism tempers Bell’s flamboyant visceral ideologistics.

Other characters attained more or less definition in the writing. Patel has a droning, sing-song, continuous speech pattern, whereas Fang’s speech is sometimes broken by abrupt hesitations every five words, a series of false starts. They form a pair, with Fong watching Patel read the news on television and vice versa, and they are not always in character. Beck talks to Keller a lot about views, present or from memory. Jameson, the scholar, reads quotations from Shklovsky, Marx, and Wittgenstein, as well as a cabinetry manual. Dumas—the secret agent?—issues cryptic one-liners dubiously related to the action.

While putting my materials into dialogue form, I added speeches that would refer directly to the apparatus of the theater. To begin with, I had all the characters introduce themselves by name. The names are surnames only, so the characters’ sexes are not prescribed by the script. By not defining specific hierarchical relations, I aimed for an institutional collectivity. I wanted to represent individuals as members of a group none of them directs and which is subject to forces beyond its control.

The play had already been handed over to the director for auditions before it was completed. Then several scenes were inserted near the end, where it seemed to need more weight. The long speeches by Patel and Fong were meant to slacken the breakneck pace and give the audience an opportunity to relax before the accelerated conclusion.

Collateral is a performance text that demands of the director and actors a maximum of interpretation.2 The Poets Theater production went through about two months of rehearsal under the direction of Eileen Corder. I viewed the auditions, one early improvisation, and, a few nights before opening, a dress rehearsal. What Eileen had done with the script was hilarious, dazzling, and darkly brooding.

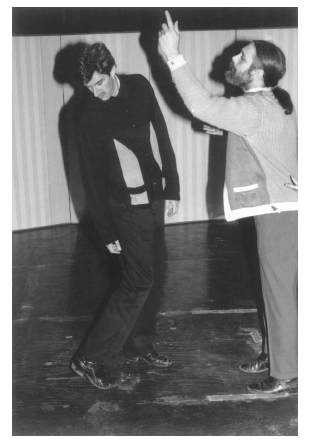

The ambiguities of the text—who, for instance, is talking to whom in the group scenes—were compounded by physical blocking that added further levels of possible interaction. Props literalizing abstract lines of dialogue undercut metaphysical projections. Dumas says, “Press and this world gives,” squeezes a foam ball painted to represent the earth, “Press on this world, it gives.”

My sense of the play is very much informed by the Poets Theater production, so much so that I now have trouble distinguishing my ideas from those that were developed in production. I even added some of the actions into the final version of the play for publication in Hills 9. For instance, in scene 10 the original script read:

Bell: … Let me show you something.

Lopez: That’s very interesting….

The space between these lines was left as an opening for action. I was shocked when I learned that for action the director had Bell suddenly turn and stab Keller, killing him. But the possibility for such violent action was suggested in the script when, several moments later, Lopez says, “Stabbing in Tenderloin Hotel / Plaintiff lodger in defendant hotel stabbed.” In performance, Lopez shouted this headline from the newspaper Keller had been holding. The gratuitously victimized Keller returns in the next scene, a “new man,” distracted from death by a member of the audience.

The beautifully lit and painted sets functioned variously, as shifting contexts suggested various scenes—a museum tour, a cocktail party, a hotel room, a pool hall, a prison visit, a train ride, a TV room, a dressing room, and the theater itself.

The props—masks, newspaper, suitcase, photographs, bed, books, television screen (a cut-out cardboard frame)—were used repeatedly in variation, just as the words of the play were. (Nearly every word in Collateral is said at least twice, each time in altered context, usually by a different speaker.) Often the props were used to extend rather than illustrate the meanings of the words. For example, when Bell said, “We don’t have salad plates. We do have this though. Click click click. Big wooden spoons,” he produced from his suitcase not spoons but masks, widening further the range of meanings. (Spoons are like masks in shape. If masks are spoons, faces must be served up like soup, as Bell’s menacing tone seemed to imply.) Later, Keller wore one of these masks as he sat reading a newspaper. In that scene, it seemed to mark him as a target for Bell’s vicious attack.

In scene 13, Lopez answers Bell’s soliloquy by repeating its verbs in order. In performance, the set was a cheap hotel room lit at night by a flashing colored light from the window. Bell stood by the window while Lopez lay asleep on the bed. His response to Bell’s speech was spoken in sleep, a set of verbal twitches suggesting dream states.

In the script, Jameson’s lengthy speeches are followed by separately numbered scenes dedicated to one-liners by Dumas. In the production, Jameson addressed Dumas, reading to him from a book and gesticulating emphatically, while Dumas, the bad student, winced, squirmed, put his fingers in his ears, and finally stood up to holler a terse non sequitur in reply. The ridicule Dumas threw on Jameson’s pompous manner set the didactic messages in perspective. While the ideas expressed—on craft, art, ideology, and intention—reflect on the nature of the play, they can’t transcend or speak from outside it.

Circumscribing the zany sight gags and off-base rejoinders was a dark sense of impending collective danger, graphically fleshed out in scene 17, when the white-gloved Dumas drew an invisible rope around the entire cast and appeared to hoist them en masse, by pulley, skyward at the blackout. Chilly dread formed the scrim before which the players matched their lucky wits. But Collateral played too fast and loose to be simply booming doom. This was no static stalemate clogged with ennui à la Beckett. The push-pull of enthusiasm and resistance created a time that was all action.

The script calls for forty separate scenes, but these were lumped together to form several longer scenes in which various interactions overlapped or took place simultaneously. The numbered scenes were used as modules to make bigger temporal structures, defined by set changes and blackouts. The script is a toolkit for making a play. The Poets Theater production took full advantage of the liberties so proposed.

SUBTEXT IN COLLATERAL NICK ROBINSON

Two levels of narrative can be traced in the Poets Theater production of Kit Robinson’s Collateral (San Francisco, 1982), in which I played the role of Bell. The more substantial and prominent is the score of physical actions created by the director Eileen Corder. Given a script which contains virtually no staging directions and no clearly delineated story line, Corder initiated a collaborative process in which author, director, and actors took part. In early rehearsals we investigated the play’s rhythmic dynamics and physicalized our encounter with the text—strategies typical of a methodology proposed by the Russian director Vsevolod Meyerhold:

There is a whole range of questions to which psychology is incapable of supplying the answers. A theatre built on psychological foundations is as certain to collapse as a house built on sand. On the other hand, a theatre which relies on physical elements is at the very least assured of clarity. All psychological states are determined by specific physiological processes. By correctly resolving the nature of his state physically, the actor reaches the point where he experiences the excitation which communicates itself to the spectator and induces him to share in the actor’s performance: what we used to call ‘gripping’ the spectator. It is this excitation which is the very essence of the actor’s art. From a sequence of physical positions and situations there arise those ‘points of excitation’ which are informed with some particular emotion.3

Within the framework of this “sequence of physical positions and situations” articulated by the director, the actors are free to create individual scores or subtexts. The subtext proceeds by narrative means which are largely interior: personal associations, memories, imaginary objectives and obstacles. It is a field of possible meanings and intentions; it can remain fluid and improvisatory within the structures of the text and the mise-en-scène. It is also a private creation whose terms and organizational principles are seldom presented directly to the audience. Meyerhold describes subtext as “the ‘inner dialogue’ which the spectator should overhear, not as words but as pauses, not as cries but as silences, not as soliloquies but as the music of plastic movement.”4The subtext I developed for Bell contained several discrete narrative threads which were variously complementary, overlapping, and contradictory. A conventional approach would have been to discard all but those which bore the most literal and linear relation to the narrative interpretation advanced by the director. But since Corder’s direction seemed designed to tease meaning from the text on a scene by scene basis rather than coerce the play into a singular narrative structure, I let my subtext remain loosely jointed and multiple. Brecht provides some encouragement for such an approach to story-making in the theater:

For a genuine story to emerge it is most important that the scenes should to start with be played quite simply one after another, using the experience of real life, without taking account of what follows or even of the play’s overall sense. The story than unreels in a contradictory manner; the individual scenes retain their own meanings; they yield (and stimulate) a wealth of ideas; and their sum, the story, unfolds authentically without any cheap all-pervading idealization (one work leading to another) or directing of subordinate parts to an ending in which everything is resolved.5

What follows is a description of scene 1 of Collateral. A general outline of the physical score appears in italics. Bell’s lines are immediately followed by an account of some of the subtextual resources I drew upon in performance.

Lopez whimpers offstage. Bell enters carrying suitcase. Lopez follows.

WHEN I SOUND A VAPOR I FEEL SECURE. SOUNDING VAPORS SECURES ME.

“Sound a vapor” at its most literal means “talk,” “vibrate breath.” It can also be played as referring to one of several activities: performing a scientific experiment (imagine sending sound waves through a gas-filled tube); taking drugs; engaging in fraud (maybe high-tech computer bank fraud). Each meaning carries a freight of associations relevant to Bell’s occupation and character. The possible roles of actor, scientist, decadent, and criminal first encountered here may be echoed and extended throughout the play.

Bell opens suitcase and removes two neckties. Bell and Lopez put them on. I OCCUR AT INTERVALS. SOME DAYS PASS ME BY ENTIRELY.

As a sarcastic come-back to Lopez’s “I don’t see how you do it, Bell,” these lines indicate Bell’s stance as wise guy to Lopez’s straight man. They set up the two as stock character types: Bell as quick-witted, light, positive; Lopez thoughtful, bulky, negative. These basic characteristics of tempo and physicality may be maintained through a variety of circumstances and subtextual choices.

At another level these lines announce and describe the function of character in Collateral. “I,” my stage persona, emerges from a field of associations by rhyme and rhythm to foreground a particular configuration, which is then allowed to dissolve back into the field, perhaps to be echoed or opposed in “my” next occurrence. It seems Bell is a theater theorist, or an actor explaining his method of taking on masks.

WHEN I TALK, WHAT I SAY MEANS ME.

A condescending jibe at Lopez: “When I talk …,” as opposed to when you talk.

Bell is boasting about his facility at inventing personae. Bell as a successful entertainer, adept at artifice for every occasion. Or as a con-man.

As a reversal of the cliché “I mean what I say” this line reveals Bell’s position on a central theatrical problem: the creation or construction of character. To “mean what you say” is the acting method of the dominant theatrical trend of this century, best exemplified and articulated by the work of Constantin Stanislavsky. How to fully inhabit a role, living the life of a character moment-to-moment—this is the goal which Stanislavsky moved toward with astonishing accuracy, founding a tradition whose basis is the fostering of empathy. In his early period Stanislavsky’s methods stressed a movement from internal processes to external manifestations, building a character from the inside out.

[The artist] must fit his own human qualities to the life of this other, and pour into it all of his own soul. The fundamental aim of our art is the creation of this inner life of a human spirit, and its expression in an artistic form.

That is why we begin by thinking about the inner side of a role, and how to create its spiritual life through the help of the internal process of living the part. You must live it by actually experiencing feelings that are analogous to it, each and every time you repeat the process of creating it.6

“What I say means me” proposes an alternative method (and ideology), perhaps best articulated by Vsevolod Meyerhold. Meyerhold’s theory of biomechanics advocated building a role from the outside in.

Constructivism challenged the artist to become an engineer. Art must have a basis in scientific knowledge, for all artistic creativity should be conscious. The art of the actor consists in organizing his materials, that is in properly utilizing his body with all its means of expression.7

This line rhymes with “I occur at intervals” in supporting a concept of character which is constructed and contingent. Instead of asking the audience to suspend its disbelief in his performance. Bell invites the audience to observe how the language of the play shapes the artifice of his role. He probably reads Brecht.

The bourgeois theater’s performances always aim at smoothing over contradictions, at creating false harmony, at idealization. Conditions are reported as if they could not be otherwise; characters as individuals, incapable by definition of being divided, cast in one block, manifesting themselves in the most various situations, likewise for that matter existing without any situations at all. If there is any development it is always steady, never by jerks; the developments always take place within a definite framework which cannot be broken through.

None of this is like reality, so a realistic theater must give it up.8

ORDINARY LANGUAGE POINTS TO ITSELF EQUALLY.

Failing any big ideas, this line can always be tossed off as “obvious”:

CONSIDER THE EARTH AS A SOUNDING PLATE, AND THE CAPITALS AS COLLECTING THE DUST INTO BUNDLES OF STANDING WAVES.

This line has a scientific ring which rhymes with the reading of “sound a vapor” (first line of the scene) as an experimental process. I visualize a demonstration of magnetic fields using carbon particles on glass.

As critical commentary on the structuring devices in Collateral, this line offers a metaphor which extends the concept of character posed in “I occur at intervals.” Consider the play (“earth”) as a musical/vibrational field (“sounding plate”), and the actors (“capitals”) as collecting textual particles (“the dust”) into characters (“bundles of standing waves”). The “bundles” suggest a process of knotting—a term Brecht uses in his discussions of character and story. Knotting joins independent and dissimilar episodes or aspects while leaving the knots visible to the audience. “The episodes must not succeed one another indistinguishably but must give us a chance to interpose our judgement.”9“Standing waves” proposes character as a musical phenomenon: a polyphonic composition of various rhythmic units.

ENGLAND AND JAPAN KNOW THIS VERY WELL.

High-class gangster talk. Reference to industrialized capitalist nations keys “criminal” narrative. Bell and Lopez as international entrepreneurs practicing high-finance fraud and extortion. In hotel room, suiting up for job.

Whistle offstage. Dumas enters. Lopez goes to Dumas. Dumas hands Lopez a note.

WHAT’S CLEAR AND DISTINCT TO YOU AND ME MAY LOOK LIKE SMOG TO AN ALEUTIAN.

A one-liner in the repertoire of Bell the comic.

This line acknowledges the partnership of Bell and Lopez in relation to some “others,” one of whom has just entered. Aleutians are: the audience, the law, other scientists.

Lopez reads note and gives it to Bell. Bell reads note.

(SHOUTS) PAGING MILLENNIA MINOR!

An exclamation of delight. The note is a tip in a crime venture.

LOPEZ, MY DARK PLASTIC WOOD!

Bell calls for his gun.

“Dark plastic wood” could be plot glue needed at this juncture to join events into a credible sequence.

VAPOR! IT CAN BE APPLIED!

Bell closes suitcase. Lopez and Bell begin to leave. Bell stops, turns back, leaves a dollar bill on stage. Bell and Lopez exit.

This brings us back to the first line, making scene 1 a loop. Lopez’s negative response to the previous line throws Bell onto his own resources. For “vapor” read “language.” Bell’s confidence springs from his ability to apply his text to describe (invent) various theatrical illusions—character, story, subtext—without being bound or determined by his inventions. This is the primary narrative statement of scene 1.

Bell is in debt to the stage for his freedom of action. He leaves a dollar as a tip for whoever cleans up after scene 1.

On paper this analysis looks like a plan for acting Bell upon which physical choices such as posture, gesture, and tempo would depend. The opposite is true. These ideas and associations occurred during rehearsal in response to the physical tasks given by the director, and in relationship with the other actors. They are readings of the text whose ground is the stage.

These readings operate on two basic levels of meaning, each containing fissures and variations. On one level they refer to a developing action narrative. Bell prepares for and commits a burglary (scenes 1 and 3), disguises himself (scene 6), appears as a speaker at a convention where he meets his victim (scene 8), commits theft and murder (scene 10), discovers he’s bungled the job (scene 12), vents his anguish (scene 13), dreams of a simple life (scene 14), is interrogated (scene 20), is tortured (scene 22), confesses (scene 26), and ends in philosophic beatitude in a public looney bin (scene 32), or perhaps a theater (scene 40).

On the second level the lines refer to the process of creating the first level of meaning. They are about acting, asserting a character, inventing and justifying motives and actions. They reveal, make conscious the processes of generating meaning in the theater. As Eileen Corder put it, “Your characters are creating characters.” In Brechtian lingo these two levels of meaning are empathy and demonstration. Both are advocated:

However dogmatic it may seem to insist that self-identification with the character should be avoided in the performance, our generation can listen to this warning with advantage. However determinedly they obey it they can hardly carry it out to the letter, so the most likely result is that truly rending contradiction between experience and portrayal, empathy and demonstration, justification and criticism, which is what is aimed at.

The contradiction between acting (demonstration) and experience (empathy) often leads the uninstructed to suppose that only one or the other can be manifest in the work of the actor (as if the Short Organum concentrated entirely on acting and the old tradition entirely on experience). In reality it is a matter of two mutually hostile processes which fuse in the actor’s work; his performance is not just composed of a bit of the one and a bit of the other. His particular effectiveness comes from the tussle and tension of the two opposites, and also from their depth.10

The particular achievement of Collateral lies in its formal precision as a vehicle for contradiction and change. It is a latticework of scenes with clearly articulated stresses, points of intersection, divergent interests. Its structure provides maximum stimulus and support for the playing out of a dramatic torque. It is active and contemplative. It fulfills Mayakovsky’s dream of a play which is capable of continual transformation, and is therefore constantly topical. Each company that performs Collateral will discover its own stories and its own ways of telling them.

NOTES

1 As originally published in Poetics Journal, this symposium on one of the San Francisco Poets Theater productions was titled “Three Versions of Collateral” and included an essay by director Eileen Corder, who did not grant permission to republish it. —Eds.

2 COLLATERAL, SCENE 1

Bell: When I sound a vapor I feel secure. Sounding vapors secures me.

Lopez: I don’t see how you do it, Bell.

Bell: I occur at intervals. Some days pass me by entirely. When I talk, what I say means me. Ordinary language points to itself equally. Consider the earth as a sounding plate, and the capitals as collecting the dust into bundles of standing waves. England and Japan know this very well. What’s clear and distinct to you and me may look like smog to an Aleutian.

Lopez: My memory banks off to the left. Still, I’m here and can breathe. My condition built this single strand of hair.

Bell: (Shouts) Paging Millenia Minor! Lopez, my dark plastic wood!

Lopez: That’s shit, Bell.

Bell: Vapor! It can be applied!

3 Vsevolod Meyerhold, Meyerhold on Theatre, trans. and edited Edward Braun (New York: Hill and Wang, 1969), 199.

4 Ibid., 36.

5 Bertolt Brecht, Brecht on Theatre, trans. and ed. John Willet (New York: Hill and Wang, 1964), 278–79.

6 Constantin Stanislavsky, An Actor Prepares, trans. Elizabeth R. Hapgood (New York: Theater Arts, 1936), 14.

7 Meyerhold, Meyerhold on Theatre, 198.

8 Brecht, Brecht on Theatre, 277.

9 Ibid., 201.

10 Ibid., 277–78.

PUBLISHED: Excerpted from Non/Narrative (1985), 5:122–38.

KEYWORDS: Language writing; performance; material text; readings.

LINKS: Michael Amnasan, from Joe Liar (PJ 10); Steve Benson, “Close Reading: Leavings and Cleavings” (Guide; PJ 2); Benson and Carla Harryman, “Dialogue: Museo Antropología, Mexico” (PJ 8); Alan Bernheimer, “The Simulacrum of Narrative” (PJ 5); cris cheek, “… they almost all practically …” (PJ 5); Abigail Child and Sally Silvers, “Rewire//Speak in Disagreement” (PJ 4); Harryman, “What In Fact Was Originally Improvised” (PJ 2); George Lakoff, “Continuous Reframing” (Guide; PJ 1); Jackson Mac Low, “Pieces o’ Six–XII and XXIII” (PJ 6); Tom Mandel, “Codes/Texts: Reading S/Z” (PJ 2); Bob Perelman, “Plotless Prose” (PJ 1); Kit Robinson, “Bob Cobbing’s Blade” (PJ 1); Leslie Scalapino, “War/Poverty/Writing” (PJ 10); Fiona Templeton, “My Work Telling the Story of Narrative in It” (PJ 5); Rodrigo Toscano, “Early Morning Prompts for Evening Takes; or, Roll ’Em” (PJ 10); Barrett Watten, “The XYZ of Reading: Negativity (And)” (PJ 6); John Woodall, detail from Gimcrack (performance) (PJ 9).

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY: Plays and Other Writings, ed. Bob Perelman, Hills 9 (1983); Kenning Anthology of Poets Theater: 1945–1985, ed. Kevin Killian and David Brazil (Chicago: Kenning, 2009); Steve Benson, Blindspots (Cambridge, Mass.: Whale Cloth, 1981); Carla Harryman, Animal Instincts: Prose Plays Essays (Oakland: This, 1989); Memory Play (Oakland: O Books, 1994); Killian, Island of Lost Souls (Vancouver, B.C.: Nomados, 2003); Jackson Mac Low, The Pronouns: A Collection of Forty Dances for the Dancers, 3 February–22 March 1964 (Barrytown, N.Y.: Station Hill, 1979); Leslie Scalapino, Goya’s L.A. (Elmwood, Conn.: Potes & Poets, 1994); Fiona Templeton, You—The City (New York: Roof, 1990); Rodrigo Toscano, Collapsible Poetics Theater (Albany, N.Y.: Fence, 2008).