Narrative Concerns

Cinema has provided poetry with many points of reference, from Hart Crane’s The Bridge to Frank O’Hara’s “Ave Maria” and John Ashbery’s “Daffy Duck.” Less familiar are avant-garde cinema’s contributions to poetics, from the modernist period to the present. Warren Sonbert (1947–95) was a San Francisco experimental filmmaker with close ties to poetry, particularly New York School and Language writers. His essay, as part of the “Symposium on Narrative” (PJ 5), addresses his limited use of narrative in nonnarrative films: narrative may provide images with emotional power, but images should be kept from being overdetermined by plot. Influenced by Soviet directors such as Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov, by the French New Wave, by a selective canon of Hollywood masters and genre films, and by the avant-garde from Andy Warhol to Stan Brakhage, Sonbert’s films are complex realizations of the material and affective possibilities of cinema. His thinking on cinematic technique—from shot selection to larger combinatory principles—owes much to Eisenstein and Vertov’s theories of montage. However, it is his use of these techniques to produce visual sequences that are both intellectually complex and emotionally rich that makes his films of particular interest to poets. Sonbert’s poetic cinema anticipated the recent emergence of “Neo-Benshi” performances, where avant-garde poetry is read with film and often music, in the Bay Area and elsewhere.

The strengths of narrative as well entail its limitations. On one level narrative could be defined as the eventual resolution of all elements introduced. This classical balance is always satisfying: when the various strands are climacti-cally tied together. But this also implies a grounding that may often enough be deadening.

A fairly interesting Jacques Tourneur film, Nightfall (1956), illustrates this point. At the opening, a man, ostensibly the hero, since he’s also the star (Aldo Ray), walks into a city bar at night. He is being watched, unawares, by two men in a car. Once in the bar a third man also begins to observe him. While seated at the bar Aldo is approached by a woman (Anne Bancroft) to borrow some money to pay for her drink as she’s mistakenly left her money at home. At this juncture the possibilities are rampant: three different sets of strangers have either approached or are observing the protagonist. What could they all want from him? What is below the surface of this rather ordinary-looking hero? Then, are any of the three sets involved with one another or are they working separately? Is Bancroft’s plea a ruse or the truth? If a ruse, is it a sexual pickup or something more ominous? At this moment when anything can happen, narrative is at its most fascinating. (In my own films I generally try to include an image of forward motion on train tracks in which several lines converge but cut before any actual track or direction is taken—it’s a metaphor for possibilities open.) In Nightfall’s case the questions are answered all too soon perhaps. Bancroft is telling the truth, the single trailing man is on his side, the men in the car are against him and none of these initial strangers are working together. But the frissons with which the first scene of the film are filled almost carry over into the entire unraveling of the work. Though settling down into a very good, standard thriller, nothing quite matches this opening assault of question marks.

Beyond this initial barrage of possibilities open, narrative can partake of shiftings in value identification as another one of its strong suits. The opening chapter of Balzac’s Splendors and Miseries of Courtesans has this in spades, in that the author always seems two moves ahead of the reader: the focus of viewpoint remains unanchored amidst a wide variety of conflicting identity figures. This avoidance of set bearings is all to the good as it supplies one of the prerequisites of art. The changing stress between comedy and tragedy in Renoir’s Rules of the Game is another instance of a profound, unsettling, architectonic strategy. Again, the major works of Hitchcock brim with this tension of paying for your laughs. (In my Noblesse Oblige shots of a “cute” kitten at play is immediately followed by an image of someone being wheeled into an ambulance, and briefly enough displayed to hopefully be disturbing). Any given must fairly soon be qualified to preclude smugness and an easily assumed attitude: Balzac and Stendhal were prime investors in this policy. Psycho and Splendors in fact partake of the same function of cheating the anticipations of the receiver (viewer/reader). In both works an identity figure is posited (Marion in Psycho, Esther in Splendors), then removed and replaced by another identity figure (Arbogast and Lucien, respectively), to which the receiver is cannily made to make a complete emotional transference, only to be removed and replaced once again by what turns out to be both works’ archvillains (Norman and Herrera). Such discomforting sleights of hand regarding character identification seem to be one of narrative’s most effective calling cards.

When narrative settles down and becomes domesticated, when a given just stays that way throughout the length of the work, it becomes inert and predictable.

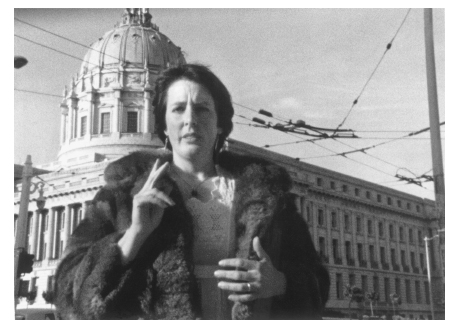

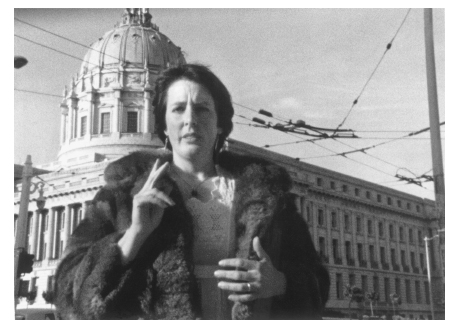

From A Woman’s Touch, © 1983 by Warren Sonbert.

In my last completed work, A Woman’s Touch (1983), which lasts 23 minutes, there is a given and then a series of qualifications, almost like a Theme and Variations. The initial set is a number of images of women involved in solitary action. All is presented positively, benignly, almost too complacently: women at work, at play, constructing, striving, succeeding—a paean to their independence. The first variation is the introduction of men: singly active as well and intercut with the women. The men here are initially conceived as threats and tinged with negative associative imagery: men drinking, men gambling, men ordering, pointing, bossing. There is a very brief (hence again hopefully disturbing) image of a man sharpening a knife. Other images show men carrying guns or dominating others within their sphere. After all this, no wonder the women might prefer to be on their own. The second variation softens the first two sets: men become less of a threat. The elements of couples, of domesticity, of sweet family existence invade the pattern of images. The same man who earlier was briefly shown sharpening a knife is now seen in a much longer shot (obviously a chef) scooping up ice cream. See? It’s not so bad. Throughout the film (in which an image of one man or woman performing an activity is always seen/felt as a surrogate for any other, different man or woman respectively performing another activity).

A specific man and a specific woman have constantly been intercut with one another though they never appear within the same frame. The woman is confident, a worker, assured, the epitome of Independence. The man is shown in contained spaces—usually a chauffeured car or in an office—and invariably giving orders and directions to others. He’s obviously a dominating force, perhaps one of repression. The first two images of the film are a woman on the phone then another woman on the phone. The last four shots of the film: 1) the independent, working woman opens a mirrored door and answers a phone, smiling and nodding her head in agreement—obviously glad to accept an offer. The mirrored door behind her closes, but it is as well in movement/flux and therefore as a metaphor suggests the situation/predicament of the viewing audience. 2) The dominating man is on the phone in what seems to be his office. He has certainly softened. His suit coat is off and he’s more relaxed than in his previous images. By the juxtaposition of these two images the viewer registers that these two “characters” have finally come together: the man is asking the woman out, or they’re married and he’s checking in, or whatever—some bond is present. Other factors: he has called her, made the move—reenforcing the traditional aggressor role. She complies, capitulates, gives in. Throughout the film there has been a movement towards domestication: an image of a woman hailing a (offscreen) cab on a city street is followed by (in an apparently different location) an image of a mobile home being transported down a road on an enormous truck. So 3) a very brief fade-in fade-out (almost like the flicker of an eye) image of the interior of a comfortable vine-covered cottage. Clichés certainly come in handy to build visual arguments. 4) In long shot, symmetrically framed, at a significant distance, the exterior of an impressively grand ranch house as a man leaves the front door and gets into his limousine and slams the door. The lines of the driveway converge in a path that leads to the house: but it is also a cul-de-sac, a dead end. The man does have the last word. All the independence that the women in the film have throughout evinced, and as well the straining towards home and domesticity, here both converge in a narrative summation of tying together the threads within a devastating conclusive context. This final surrogate man is in a suit—just like our dominating hero. The slamming of the car door is the opposite of Nora’s exit in A Doll’s House. The enclosures of the house and car represent safety, insularity, complacency and, at the same time, wealth and power. Man is still calling the shots. In A Woman’s Touch the men have the last word from the force built up via montage into this lost image. The converging lines of the driveway represent a road, a passage, an escape—to flee (like the converging lines of the railway station at the beginning of Marnie), but the cul-de-sac at the end of these lines diverts/inundates/cancels this attempt at escape, at Independence.

PUBLISHED: Non/Narrative (1985), 5:107–10.

KEYWORDS: cinema; nonnarrative; avant-garde; visuality.

LINKS: Rae Armantrout, “Silence” (PJ 3); Abigail Child, “The Exhibit and the Circulation” (PJ 7); Child, “Outside Topographies: Three Moments in Film” (PJ 8); Michael Gottlieb, five poems (PJ 10); P. Inman, “Narrating (Moving) People” (PJ 9); “Poets Theater: Two Versions of Collateral” (Guide; PJ 5); Larry Price, “Harryman’s Balzac” (PJ 4); Jed Rasula, “What Does This Do with You Reading?” (PJ 1).

SELECTED FILMOGRAPHY/BIBLIOGRAPHY: Where Did Our Love Go (1966); Hall of Mirrors (1966); Amphetamine (1966); Truth Serum (1967); The Tenth Legion (1967); Ted and Jessica (1967); Connection (1967); The Bad and the Beautiful (1967); Holiday (1968); The Tuxedo Theatre (1968); Carriage Trade (1971); Rude Awakening (1975); Divided Loyalties (1978); Noblesse Oblige (1981); A Woman’s Touch (1983); The Cup and the Lip (1987); Honor and Obey (1987); Friendly Witness (1990); Short Fuse (1991); Whiplash (1995; posthumously completed, 1997); Alan Bernheimer, "What Happens Next," in Rae Armantrout et al., The Grand Piano 8:187–204; Steve Anker, Kathy Geritz, and Steve Seid, eds., Radical Light: Alternative Film and Video in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1945–2000 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010).