8

Keeping Things Confidential

O'Hara's brush with Confidential magazine in 1957 was one of the weirdest experiences of her life, but not because the story it printed about her was true (it wasn't) or even shocking (in fact, it was rather mild). What made the incident unusual was her excessive reaction to it, and then how that reaction seemed to mobilize others who'd been smeared by the scandal sheet in worse ways over the years, eventually resulting in its demise.

In many ways, Confidential was the National Enquirer of its day—not that this was necessarily a bad thing. Today we know much more about stars than we need to; every time they blow their noses it gets a headline somewhere. But in the 1950s they were protected by their press agents and the studios, so it was probably inevitable that a magazine like Confidential would come along as a kind of corrective. It let the greater public know that its idols had feet of clay.

Confidential first came out in late 1952 and caused an immediate sensation in an industry that had always airbrushed anything smacking of scandal. It was published every two months, and at a cost of a mere quarter an issue, it was highly affordable among those whose reading tastes didn't run to Dostoevsky or Sartre. Printed on red and yellow pulp paper, it left no doubt about its intention: to take down the high and mighty of Tinseltown's hallowed halls. Confidential's founder was Robert Harrison, a Lithuanian Jew from New York's Lower East Side. He had a history of publishing girlie magazines with titles like Titter and Wink. He had, in one writer's view, “the face of a lordly asthmatic falcon.”1

The first issue of Confidential sold a whopping 150,000 copies. It featured a story on a gay wedding, an article with the enticing title “I Was Tortured on a Chain Gang,” and an array of photographs culled from Harrison's pornographic magazines. The chain-gang story was false, and the gay wedding, allegedly set in Paris, was actually filmed in Harrison's own apartment. (Many of his “exclusives” were anything but, and the accompanying photographs often featured Harrison in disguise, to save money on models.) Harrison upped the ante in August 1953 with a story that claimed Joe Schenck, then chairman of Twentieth Century–Fox, had tried to block Marilyn Monroe's wedding to Joe DiMaggio. The magazine flew off the shelves, selling a record 800,000 copies.

Harrison made it his ambition to bring Hollywood's dream factory to its knees. He had a lot of material to work with in an industry notorious for its deceptions. He knew that once stars came to prominence, they often had their biographies modified to look exotic and their eight-by-ten glossies touched up. Interviews consisted of prearranged questions that studiously avoided any whiff of past misbehavior. Being asked to name their favorite color was about as invasive as the questions got.

In many ways, the stars were prisoners of self-imposed gilded cages. Ava Gardner liked to say, “We were the only pieces of merchandise allowed to leave the factory.” O'Hara admitted, “If I was told to go somewhere, I went. Even parties were business. You have to dress for business, make yourself up for business.” Show business was the business of show.2

With O'Hara, the spin doctors pumped the Irish angle. There had been a special relationship between the United States and the Emerald Isle ever since the famine of the late 1840s resulted in large numbers of Irish immigrants, and a pretty continuous flow thereafter. Female Irish stars were thin on the ground (Maureen O'Sullivan, Greer Garson), but there were many male A-listers with Irish blood, including James Cagney, Gregory Peck, Spencer Tracy, and Gene Kelly.

O'Hara's theatrical past was often alluded to as well. Dublin's Abbey Theater was world famous, and her association with it, however brief, didn't do her any harm. She also had “pedigree” in her family tree: her mother had been an operatic contralto, and her father was a successful businessman who owned a share of a football team. Such credentials weren't to be sneezed at, but she was still vulnerable. She'd led a double life with George Brown—her secret husband. Now she was leading one with Enrique Parra as well, and coming to the end of one with the secretly alcoholic Will Price. Confidential could have had a field day with such stories.

The fanzines turned a blind eye to anything unsavory about movie stars. As one writer put it: “Theirs was supposed to be a life of sunshine, pleasure and endless lovemaking, where the living was easy amid orange blossoms and sea breezes, and everyone stayed eternally young and devastatingly beautiful.”3 Nobody needed a picture in the attic, like Dorian Gray—just the phone number of their local plastic surgeon.

O'Hara sidestepped the surgeon's scalpel. That's not to say her appearance was perfect. She always thought her face was too square and her jawline too narrow, and she had a crooked tooth. The studio wanted to remove it and replace it with a false one, but she refused. When she was informed her nose was too big, she also refused to have anything done with that. Sophia Loren had the same problem. Hollywood liked retroussé noses, but neither of these women wished to indulge such a silly whim. O'Hara told the moguls in no uncertain terms, “My nose comes with me. I've got a big square face and I need my big nose. If you don't like it I'll go back where it came from.” The ploy worked, and the nose stayed. On issues like this, she wasn't to be tampered with. It was only when it came to choosing films—and husbands—that she faltered.4

She fell afoul of Confidential in March 1957 when it carried a story headlined “It Was the Hottest Show in Town When Maureen O'Hara Cuddled in Row 35.” The gist of it was that she'd been in the balcony of Grauman's Chinese Theater with a “south-of-the-border sweetie,” but not to watch The Robe, which was playing at the time. The incident had supposedly occurred the previous November and been witnessed by the assistant manager at Grauman's. (In fact, two Grauman employees, assistant managers James Craig and Michael Patrick Casey, claimed they saw the erotic grope, although they gave different dates for it. Craig sold the story to Michael Mordaunt-Smith, a London-based representative of Confidential.) O'Hara had entered the theater, the article stated, “wearing a white silk blouse neatly buttoned. Now it wasn't.” Her date's “spruce blue suit” had also been removed. Further, she had taken “the darnedest position to watch a movie in the whole history of the theater. She was spread across three seats—with the happy Latin American in the middle seat.”5

O'Hara was probably targeted because she hadn't been stung before. With this magazine, content had little to do with evidence and everything to do with naming names. Even Harrison admitted, “We were running out of people.”6 It was simply O'Hara's turn. Up until now she'd been a protected species—possibly because, being such a homebody, she wasn't featured in the “Out and About” columns of the tabloid papers that fed the industry and therefore wasn't seen as hot copy. But that was about to change.

According to the article, the manager coughed repeatedly as a gentle hint to the woosome twosome to stop their canoodling, but “for all the reaction he got from Maureen and her rumpled boyfriend, he could have had double pneumonia.” What they were doing “threatened to short-circuit the air-conditioning system.” Eventually, he had to issue the admonition, “It might be better if you left the theater.”7 Row 35 had never felt hotter.

The story was obviously concocted to exploit O'Hara's relationship with Parra, which was well known to Hollywood insiders. Its source is widely believed to have been gossip columnist Mike Connolly, who wrote elsewhere: “Word wafts up from Mexico City that Maureen O'Hara is having a whirl.” He added that if she had her heart set on “that Mexican,” she should bear three things in mind: “(1) He's married and has a 17 year-old daughter, (2) Mexicans don't divorce easily in Mexico, and (3) He doesn't own that hotel or that bank but merely works for the people who own them.”8 The implication was obvious: she was after his money.

One of the reasons O'Hara was so shocked by the allegations was that she'd been treated so well by the press up to this time. Almost every article printed about her extolled her beauty, her charm, the fact that she wasn't a diva and didn't go gallivanting around Bel Air to wild parties. She was, if you like, the full package: an actress who didn't throw tantrums yet was forthright, who stood up for her rights yet “knew her place,” who didn't threaten the established order yet wasn't intimidated by it, who was neither prudish nor outré—at least until Robert Harrison came along.

She was understandably furious about the article and immediately filed a $5 million suit against the magazine. Soon afterward, two FBI agents were sent to stay in her house because they'd heard through the grapevine that Confidential intended to send a naked man into her boudoir and photograph them together to bolster the earlier story. That fortified her resolve more than ever.

By this point, a number of other lawsuits were pending, most notably one from Lizabeth Scott, based on the allegation that she was a lesbian, and one from Robert Mitchum, who'd been the subject of an almost Pythonesque smear in a 1955 story with the appetizing header: “Robert Mitchum…The Nude Who Came to Dinner!” At a wrap party for the Charles Laughton movie The Night of the Hunter, hosted by the director, Mitchum had allegedly stripped down to his socks, sprinkled his whole body with catsup, and proclaimed to the assembled gathering, “This is a masquerade party, isn't it? Well I'm a hamburger.”9

The young Maureen FitzSimons on the cusp of stardom.

An early studio still shows her in “sultry siren” mode. This image wouldn't last long.

A dramatic scene from The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

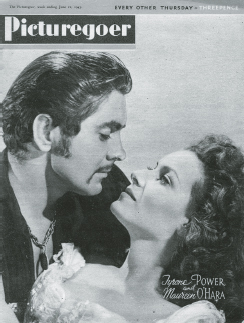

A hirsute Tyrone Power looks somewhat like Rhett Butler as he cradles “Scarlet” O'Hara in his arms in a posed publicity still from The Black Swan. (Courtesy Sales Production)

She appeared opposite a rougher-than-usual Tyrone Power in The Black Swan.

Staving off Power's romantic advances in The Black Swan.

Looking every inch the happily married woman—though this was far from the case.

O'Hara groomed to perfection against a luxurious backdrop.

She may not have done “leg art,” but this shot of her plunging neckline more than satisfied hot-blooded males.

At home with her beloved dogs.

Posed studio still with Joel McCrea from Buffalo Bill in 1944.

A smoldering O'Hara shows off those famous green eyes, with her hair uncharacteristically parted in the middle.

A relaxed pose that didn't match her fiery screen persona.

Another stunning mid-1940s portrait.

O'Hara gazes adoringly at Henry Fonda, one of her favorite costars, in The Immortal Sergeant. (Courtesy Sales Production)

A fairly typical 1940s pose emphasizing her stubborn demeanor and strong character. (Courtesy Sales Production)

In heated discussion with Anthony Quinn and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. in Sinbad the Sailor in 1947.

Displaying a more triumphant mood with Fairbanks.

In Miracle on 34th Street (1947) O'Hara starred opposite the young Natalie Wood.

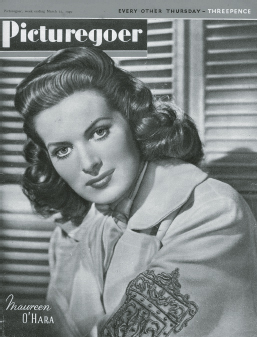

O'Hara's Celtic mood on a 1949 magazine cover. (Courtesy Sales Production)

The “come hither” look usually promised more than it delivered. (Courtesy Sales Production)

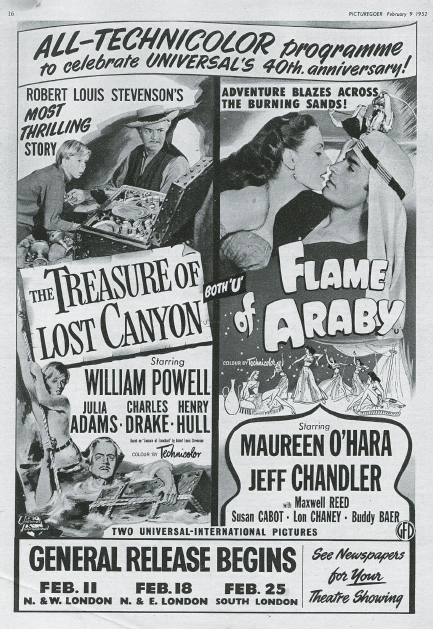

Poster from Flame of Araby, one of her “Maureen Sahara” outings. (Courtesy Sales Production)

Poster from Kangaroo, one of her less felicitous assignments. (Courtesy Sales Production)

The scowling firebrand.

With John Wayne in her favorite and most famous movie, The Quiet Man.

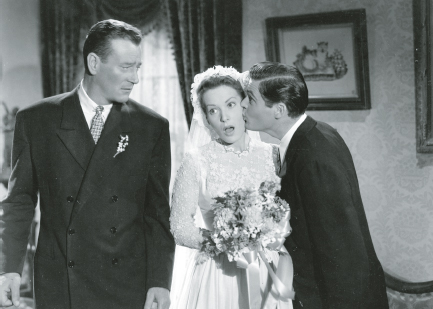

The wedding scene from The Quiet Man.

O'Hara's classic “don't mess with me” expression that became her trademark.

She could also show great charm.

Distaff knight-errant opposite Errol Flynn in Against All Flags in 1952.

Squaring up to Flynn with typical arrogance in Against All Flags. (Courtesy Sales Production)

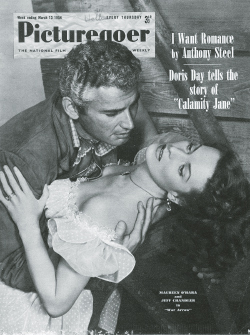

Although she seems to be feeling the heat of Jeff Chandler's ardor, in reality she likened the experience to “acting with a broomstick.” (Courtesy Sales Production)

The (anti)climactic would-be nude scene from the ill-fated Lady Godiva.

An earlier shot from Lady Godiva.

Wrapping up for the Irish weather in the late 1950s.

O'Hara made a transition from comely maiden to trendy mother for The Parent Trap.

With her good friend Brian Keith in The Parent Trap.

In a dramatic scene with Keith from The Parent Trap.

Sparring with the Duke in one of their late “spoof” westerns, McLintock!

O'Hara made a controversial return to movies in 1991 to star in Only the Lonely after a twenty-year hiatus.

O'Hara was confident she'd win her case, as she'd been out of the country at the time of the alleged incident. (A stamp on her passport testified to that fact.) She was also aware that Confidential was suffering under the weight of the other suits. After nearly five years of taking sucker punches from the scandal sheet, Hollywood was finally starting to fight back. O'Hara had always been somewhat litigious, and she probably would have sued even in the absence of a profusion of other angry stars. But the timing of the story, printed when the hunted were poised to become the hunters (including Tab Hunter), made it even more likely that she'd sue.

On March 27 Los Angeles district attorney William McKesson launched a general action against the scandal magazines on the grounds that they flagrantly conspired to libel people. Shortly afterward, California governor Goodwin Knight called for such magazines to be banned outright. O'Hara welcomed these developments and offered to testify on any related matter that concerned her. So did others who felt they'd been besmirched by Confidential and other rags. O'Hara's alleged cuddle with her “south-of-the-border sweetie” was the first case on the roster. One filed by Dorothy Dandridge was scheduled to follow it, as were other cases involving Mitchum, Gary Cooper, Mae West, Liberace, and June Allyson.

O'Hara's case began on August 7. Assistant district attorney Clarence Linn gave his opening statement to a jury of five women and seven men in the Los Angeles Hall of Justice. He described Harrison as the “Mr. Big” of an operation that used prostitutes to lure celebrities into compromising positions; Harrison then followed such “stings” by recklessly publishing falsehoods about the stars. Art Crowley, for the defense, responded by telling the jurors that Confidential's reports were published without malice and were true in all important particulars.

The first witness for the state was Howard Rushmore, a leading anticommunist columnist for William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal-American. Rushmore had worked for Confidential but left after Harrison suggested his writing was too right wing and would have to be toned down. (Rushmore, a former member of the Communist Party, had turned against anyone with “red” affiliations after he became friendly with J. Edgar Hoover. In time, he became one of Senator Joseph McCarthy's key witnesses at the House Committee on Un-American Activities hearings.) Rushmore testified that Harrison urged his staff to resort to any means necessary to dig up juicy tidbits on Hollywood celebrities, including paying prostitutes and known homosexuals to put stars in compromising positions. His testimony, though convincing, didn't sit well with the jurors. They probably saw him as a turncoat as well as an ex-member of the operation he was now impugning.

The day before O'Hara testified, prosecution witness Polly Gould was found dead in her apartment from an overdose of sleeping pills. Was it suicide? Murder? Gould was an interesting figure who had been playing both ends against the middle. She'd been on Harrison's payroll, keeping him informed of impending legal moves against him, while simultaneously liaising with the district attorney and acting as a “stoolie” for him.10 The plot thickened.

The O'Hara case became more like slapstick than sleaze when James Craig was called to testify. He said O'Hara appeared to be drunk on the night in question and was sitting across the lap of a short, dark man. When the jurors were unable to form a mental picture of the scenario, one of them, LaGuerre Drouet, asked Judge Walker if they could visit Grauman's and act out the grope. Astonishingly, Walker went for the idea, so the entire courtroom—bailiffs, lawyers, judge, and jurors—boarded a bus and headed for Hollywood. The spectacle drew a crowd, and reporter Theo Wilson wrote that the highlight of the event was watching a bailiff try to free the seriously overweight Drouet from a seat in row 35, where he'd become lodged. He had to be prized out in the end. It was arguably funnier (and more dramatic) than any of O'Hara's recent movies. Harrison must have been delighted at the publicity.

The slapstick-style developments gave O'Hara pause, and she considered dropping her case. She wasn't sure what to do until George Murphy, president of the Screen Actors Guild, expressed his belief in her innocence and urged her to press ahead. “I saw myself as Joan of Arc,” she blared afterward. But then Murphy dropped a bombshell: the film industry wasn't going to back her. She was shocked but thought: “To hell with them, I'll go by myself. And I did.”11 Well, not quite. Her two brothers flanked her each day as she walked to and from the court. So did her sister Peggy, the nun, whom she'd flown from the convent to vouch for O'Hara's “spotless character.”12

As she took the stand, O'Hara chirped “Up the Irish!” to nobody in particular. This was a Macdonald Carey line from Fire over Africa, the film that was her alibi. She informed the defense attorney that the article had devastated her as well as Bronwyn, who cried herself to sleep at night “because children at school were talking about the scandal.”13 That personal detail seemed to get the spectators on her side. She spoke confidently throughout her testimony, admitting that she had a Mexican boyfriend in 1954, but when asked whether the two of them had gone to Grauman's, she replied defiantly, “Never!” Several defense witnesses contradicted her on this, including one who testified she had practically had sexual intercourse in her lover's lap. A clerk who worked at Grauman's candy counter disputed her testimony that she'd been to the theater only twice, both times with her brother. The clerk stated that after one of O'Hara's visits to the theater, the ushers were all abuzz about what had happened in row 35.

In her autobiography, O'Hara chronicles the moment she debunked such piffle:

The dramatic courtroom climax came when Confidential testified, on the record, and gave the precise date and time the incident in the theater supposedly occurred. That proved fatal for them and we were ready for it. In a moment of great drama, I promptly whipped out my passport and showed it to the judge. The official dated stamps proved that I wasn't in the United States of America then. I was in Spain making Fire over Africa for Columbia pictures. (No one connected with the picture ever came forward in my defense.) The courtroom broke into applause and the judge had to quiet it. My passport proved my innocence. Confidential was found guilty of conspiring to publish obscenity and libel. My victory was the first time a movie star had won against an industry tabloid. Confidential magazine would never survive the loss in court and shortly thereafter passed into history.14

This is stirring stuff, but there are a few problems with her interpretation of events. First of all, the magazine wasn't found “guilty,” and she didn't gain a “victory.” She also neglects to mention that the so-called witnesses to her indiscretion dug in their heels, even after she produced the “irrefutable” passport evidence. Although the assistant manager backtracked, admitting it might have been more of an “affectionate embrace” than an orgiastic display, he otherwise stood by his version of events.15 A subsequent lie detector test also proved inconclusive.16 Matters dragged on long after this, both in and out of court.

The incident allegedly occurred on November 9, 1953, but O'Hara's passport proved she had left the United States a month earlier and didn't return until January of the following year. According to an August 1957 article in the Irish Times, the manager of the Dorchester Hotel in London claimed O'Hara had stayed there from November 20 to December 22, 1953, but these dates are largely irrelevant.17

Things started to go wrong for O'Hara when both Liberace and Dandridge decided to settle their claims out of court. It's unknown why they chose this course of action, as they both had strong cases. Was it fear of the unknown? A reluctance to take on Harrison, who could seemingly concoct a scandal if somebody upset him? Or was there a tacit acceptance in the industry that scandal sheets were a fact of life, so it was better not to tussle with them?

O'Hara's lawsuit, along with the others, was referred to as “Hollywood vs. Confidential.” In a general defense of himself, Harrison dictated this message from his New York office: “California has accused us of a crime, the crime of telling the truth. Hollywood is in the business of lying. Falsehood is a stock in trade. They use vast press-agent organizations and advertising expenditures to build up their stars. They glamorize and distribute detailed—and often deliberately false—information about them…. They have the cooperation of practically every medium except Confidential. They can't influence us. So they want to ‘get’ us.”18

Fred Meade, the husband of Harrison's niece, took the stand for the defense. He argued that many of the litigants couldn't reasonably complain because the stories about them hadn't negatively impacted their careers. “Take Robert Mitchum,” he began. “He's a convicted narcotics user, has served time on a Georgia chain gang, and was tossed out of his last picture for being obnoxious.” Notwithstanding these facts, “his income continues to increase since the Confidential story.”19 As for O'Hara, Meade charged that her husband had accused her of “openly consorting with a married man, while she herself was married and [had] her own child with her. She has not been hurt.”20

These arguments were clever and, to a large extent, true. As a result, the prosecution decided not to call most of its celebrity witnesses to testify. But in the third week of the trial, a group of organizations including the Writers Guild, the Screen Actors Guild, the Society of Cinema Photographers, and the Association of Motion Picture Producers joined forces to put their side of the story across.

The trial dragged on for six weeks, after which the jury deliberated for another fortnight. The result was a deadlock, with only seven jurors favoring conviction, so the judge declared a mistrial. Both sides claimed victory, but the state attorney general recommended a retrial, which would be funded by the taxpayers on the state's side, but not on Harrison's. It was a deliberate ploy to rattle the publisher, and it worked. He was loath to fund another trial, so he compromised. He agreed to pay a fine of $10,000 and to back off celebrity scandalmongering in the future, concentrating instead on more general issues such as consumer fraud and insurance scams. This was a bitter pill for him to swallow, but he knew he had no choice. Harrison's legal fees alone had cost him $500,000. He later settled out of court with O'Hara, Liberace, and Dandridge to avoid the expense of another protracted hearing.

O'Hara liked to think she put Confidential out of business. Tab Hunter agreed. In his view, she turned out to be “the crucial witness for the prosecution,” the one that caused the pillars of the Confidential empire to crumble. “Leave it to a fiery Irish redhead,” he exulted in the trial's aftermath.21 O'Hara's case finally ended in July 1958 when she settled out of court for an undisclosed sum. A caption in the Irish Press simply stated that she'd “dropped” her million-dollar suit, but the terms of “any settlement O'Hara might have received remained secret.”22

A more worrying upshot of the case was that O'Hara became persona non grata with the studio chiefs, for some reason. The fact that she underwent an operation for a slipped disk didn't help her chances of landing plum roles either. For four months after the operation she had to wear a neck-to-ankle brace.23 Action movies would be out of the question for her now. She used the time off to take voice lessons (she would eventually release two musical CDs) and to move her parents to California, where she'd bought a house for them. She wouldn't get another film offer until Our Man in Havana came up in 1959. Was there a connection between this dry spell and her court case? Nobody knew for sure. She wasn't blacklisted because of it, but one could say she was “graylisted,” having suffered negative personal publicity for the first time in her career.

Robert Harrison surveyed other publishing options after Confidential closed down, but none of them came to anything. He spent his last days in a Manhattan hotel under an assumed name. Howard Rushmore suffered a much more horrific fate, as did his wife, Frances. After the trial she experienced problems with drink and depression, at one point throwing herself into Manhattan's East River in an unsuccessful attempt to drown herself. In December 1957 her husband chased her from their New York home with a shotgun, and her psychiatrist advised her to leave him. She did, but in January 1958 Howard asked her to meet him for lunch, and she agreed. After lunch an argument broke out between them and continued when they got into a cab. A few minutes later, Rushmore drilled two bullets into Frances's head and then turned the gun on himself. The news broke on the radio while Harrison was in another cab at the other end of town. The misinformed driver said to him, “Did you hear that? The publisher of Confidential just shot himself in a cab.” Harrison experienced a weird sensation: he was the publisher of Confidential, and he was in a cab—it was as if the driver was talking about him. He outlived Rushmore by twenty years, but O'Hara's case had caused his empire of sleaze to come tumbling down around them all like a house of cards.