On 30 September and 1 October 1988, during the final days of the Seoul Olympics, live snakes were discovered on the floor of three movie theatres in Seoul screening Adrian Lyne’s Fatal Attraction. Multiple screenings were cancelled, yet the film’s distributor UIP declined to push for an investigation and the incident was not reported in the press. Several months later, on 16 February 1989, four young men carrying knives cut gashes in the screen at Sinyeong Theatre, which was presenting another UIP release, the James Bond film The Living Daylights. Then on 27 May, a cleaning woman discovered ten snakes and four containers of ammonia on the floor of the Cinehouse Theatre between screenings of UIP’s third release, Rain Man. This time, police opened an investigation and the US Embassy lodged an official complaint with the South Korean government. Later in the summer, President George H. Bush responded to a letter from Korean film directors and warned against further acts of sabotage (see Lee Hyeong-gi 1989). However, on 13 August, a string of further incidents took place at six theatres in Seoul screening the UIP releases Batteries Not Included and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. At 4:30am, a Molotov cocktail thrown in an empty screening room at the Cinehouse Theatre destroyed ten seats and caused two million won ($2,300) worth of damage. Then at various times throughout the day, tear gas powder was dispersed at five theatres, sending viewers rushing for the exits (see Lee Yeon-ung 1989).

The Motion Pictures Association of Korea, which had been organising peaceful protests in front of Seoul movie theatres since September 1988, denied any connection with these incidents; however, it did release a statement saying, ‘Until these theatres cancel their contracts with Hollywood branch offices, which are impeding the development of Korean cinema, such incidents will continue to occur’ (quoted in Lee Yeon-ung 1989: 14). The following year, one director and one screenwriter were arrested in connection with the crimes; they were eventually released after serving seven months of a two-and-a-half year sentence.

Just as in the previous year activists had waged battles on the streets against the authoritarian power of the state, in 1988 filmmakers took up what they believed to be a life and death struggle over the fate of Korean cinema. Although the industry was facing multiple challenges at this time, from cooling audience interest to a crisis in film financing, most filmmakers believed the direst threat to be competition from Hollywood. And the nature of that competition had just shifted radically, with a change in film policy that permitted Hollywood branch offices to operate on Korean soil.

In the past, local films had been protected to some degree from competition against Hollywood through import quotas and other government regulations. The local market was closed to foreign distributors, who instead had to sell release rights to Korean companies. From 1988, however, US distributors such as UIP (which handled international distribution for Paramount, Universal and MGM/UA), Warner Bros., Twentieth Century Fox, Columbia and Disney received permission to establish branch offices in Seoul and to operate in the Korean market without restrictions. The Hollywood studios were well known for their aggressive distribution strategies, marketing know-how and seemingly unlimited financial resources. Many Korean film companies, by contrast, were on their last legs, as the system that had shaped their development since the early 1960s had started to crumble.

The old system

A close look at the policies that governed the Korean film industry from the 1960s to the mid-1980s paints a telling picture of how an authoritarian government exerts control. A year after taking power in the May 1961 coup, Park Chung Hee enacted the Motion Picture Law (Yeonghwa-beop), which served as the film industry’s regulatory blueprint. The law covered various aspects of filmmaking, but one of its primary effects was to consolidate the film industry into a limited number of companies, and to make them dependent on the government for their long-term success. To make films, production companies were required to hold a licence from the government. Independent production was outlawed. Stringent requirements were also placed on the licensing process such that only the largest and best capitalised companies in the industry could comply. For example, the law (seemingly taking the old Hollywood studio system as its model) required film companies to own studio space, sound recording and laboratory facilities, a lighting system, at least three 35mm cameras and to have at least two full time directors and several full time actors under contract. Each company was also required to produce a minimum of 15 films per year (see Standish 1994: 73). As a result, only a few large companies were able to meet the requirements, and those that did took care to maintain a good relationship with the government.

If the licensing system was the stick, then the right to import foreign films was the carrot that kept film executives focused on the government’s priorities. Only a small number of imports were allowed into the country each year; in the early 1980s, the annual average was about 20–25 films. Virtually all these films performed well at the box office, given that the restricted flow of Hollywood and foreign cinema created a pent-up demand. However the government provided companies with import permits for only one film at a time, and only after certain conditions were met. Although the specific terms changed almost on a yearly basis, some of the conditions companies had to meet in order to import one foreign film included: producing and releasing three Korean features; winning the top prize at the local Grand Bell Awards; winning an award at an international film festival; producing a film that earned the highest export dollars in a given year; or, in the 1970s especially, producing a ‘quality film’ (usu-yeonghwa) made to reflect government policies or priorities (see Bak Ji-yeon 2005: 241).

The basic philosophy behind the system was to force companies to reinvest their profits from imports back into local production. The measures were successful in ensuring that a large number of Korean films were produced in each year; however, it also gave producers no incentive to invest in infrastructure or to improve the quality of local films. If, as was the case with many film companies, the only reason to produce a Korean film was to move one step closer to securing an import permit, then it only made sense to produce it as quickly and cheaply as possible. The system failed to encourage the raising of technical standards (post-dubbing of dialogue tracks remained the norm all the way to the mid-1980s), and created a mindset that local films were fundamentally inferior to foreign cinema.

If there was one silver lining, it was that directors who were prepared to deal with rushed schedules and low production values that were endemic to the system – and to avoid trouble with censors – were free to shoot films with little interference from above or pressure to conform to commercial expectations. Some of the most interesting Korean films of the 1970s and 1980s, such as Kim Ki-young’s Iodo (Ieodo, 1977, a work which ironically was classified as a ‘quality film’), Kim Soo-yong’s Night Voyage (Yahaeng, 1977) or Lee Jang-ho’s Declaration of Fools display a creative energy and unpredictability that more than compensate for their low production values and lack of craftsmanship. Director Im Kwon-taek, for his part, found the freedom to distance himself from genre filmmaking and explore a new film aesthetic with the ‘quality films’ The Genealogy (Jokbo, 1978) and The Hidden Hero (Gitbareomneun gisu, 1979). Nonetheless, these were exceptional cases, and the majority of films produced in this period were little seen and soon forgotten. The local industry’s failure to maintain even a minimal level of commercial quality was one of the factors behind a precipitous drop in annual theatrical admissions, from 166 million in 1970 to 44 million in 1984.

Policy revisions and the new producer

The Motion Picture Law was amended in 1963, 1966, 1970 and 1973, either to fix perceived faults in the system or (in 1973 especially) to strengthen government control even further, but the nature of the relationship between the government and the film industry remained constant. However, two more amendments adopted in the 1980s would, in contrasting ways, pave the way for the birth of a new film industry. The fifth revision, passed in December 1984 and put into effect in July 1985, freed up regulations concerning production and opened the door for a new generation of producers to enter the film industry. These reforms, which young producers had been requesting for years, did not represent a sudden change of heart on the part of the Chun administration; instead they served as a concession to the local industry in advance of the sixth revision, enacted in 1987, which opened the Korean film market to foreign competition. Both of these policy reforms would have a transformative effect in the long term, in ways that few observers could have predicted at the time.

The fifth revision of the Motion Picture Law contained three important reforms. The first was to replace the licensing system for production companies with a simple registration system, under which producers were required only to fill out certain forms and a provide a cash deposit (150 million won, reduced to 50 million in 1986). Companies were required to produce one feature film per year or else their registration would be annulled, but otherwise the government ceased to be involved in deciding which companies would be allowed to engage in production. Secondly, the revision legalised independent film production for companies or individuals who did not have the means or desire to officially register with the government. Up to one independent film per year could be produced, if a notice was submitted to authorities and certain capital requirements were met. Censorship procedures, of course, remained in place for independent films, but at one stroke this reform drastically lowered the barriers to entry for outsiders who wished to become involved in filmmaking. Finally, the third major change was to sever the link between film imports and local production, ending the days of the ‘quota quickie’. In the coming years, virtually all official restrictions on film imports would be lifted.

The concrete effects of the fifth revision can be seen in the statistics: the number of domestic film production companies registered with the government jumped from 25 to 98 in the years 1985 to 1989. These figures do not include independents, so it is clear that a vast number of new producers entered the film industry in this period (see Jo 2005: 153).

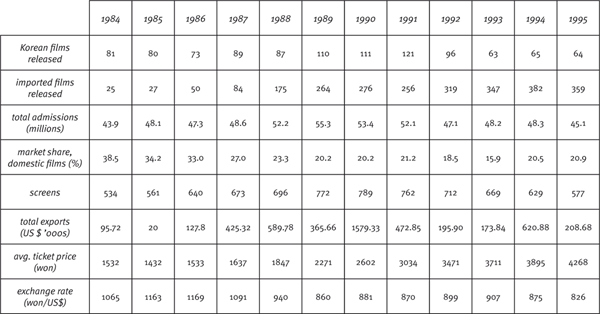

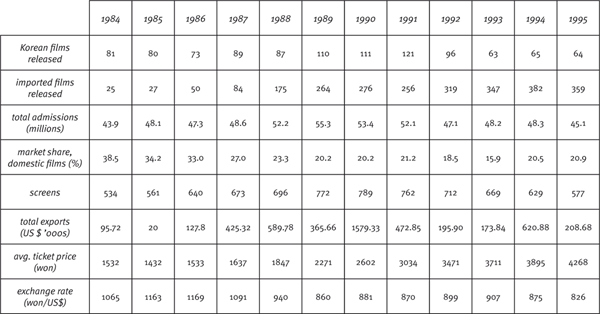

Meanwhile, the number of imported films exploded. While only 25 foreign features were imported in 1984, by 1989 there were 264, more than a ten-fold increase. The higher numbers also resulted in a greater diversity in the origins, genres and styles of films. Among the 25 titles imported in 1984 were four from Hong Kong (including Project A and Wheels on Meals), one from Taiwan (The Young Hero of Shaolin), one Italian-US co-production (Once Upon a Time in America) and 19 from the US, including E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial and Terminator. The totals from 1989 include 96 films from the US, 89 from Hong Kong, 26 from Italy, 13 from France, ten from Taiwan, six each from the UK and West Germany, two each from Argentina, China, Spain, Sweden and the USSR, and one each from Australia, Denmark, Indonesia, the Netherlands, Poland, Switzerland and Turkey.

Table 1: Film industry statistics, 1984–95. Source: Korean Cinema Yearbook

However, one of the most far-reaching effects of the fifth revision was to open the door to a younger generation of producers, many of whom would bring new ideas and working methods that would be instrumental in modernising the industry. It may be instructive to compare and distinguish between the new producers and the new directors of this period. Both were, in a sense, trying to overcome the legacies of authoritarian rule: the New Wave directors were aiming to break free of old ideologies and launch a new, socially relevant cinema, while the producers had inherited a broken industry that had been misshaped by decades of harmful film policies. Producer Shin Chul asserts that in the late 1980s, ‘Nobody was thinking about how to develop the film industry, the issue was merely to fight for survival’ (interview with author, November 2008). But as time passed, producers and other industry figures would devote themselves with zeal to the building of a modern, smoothly functioning infrastructure that could support local cinema.

Shortly after the adoption of the fifth revision, another major reform shook the industry. Passed in December 1986 and enacted in July 1987, the sixth revision was the end result of a long process of negotiation with US trade representatives. The Motion Picture Export Association of America (MPEAA) had been lobbying for the opening of the Korean film market since the 1970s; however, it was only in the mid-1980s when – anxious to secure Korean automobile manufacturers greater access to the US market, and threatened with trade retaliation under the United States’ infamous ‘Super 301’ clause – the Chun administration struck a deal.

The agreed-upon reforms were initially included in the first Korea-US Film Agreement of 1985, and later incorporated into the sixth revision. The biggest change, as noted above, was to grant foreign film companies the right to operate branch offices on Korean soil. This not only made it possible for the Hollywood studios to release their own films in Korea, it also gave them the opportunity to push for the modernisation of the Korean system from the inside. In addition to this concession, a government-imposed ceiling on prices paid for imported films was abolished, as well as a regulation that limited film companies to importing only one film per year. Various fees were also eliminated, including an import tax originally set at 150 million won per film, which was paid into the Domestic Film Promotion Fund. Finally, Korea agreed to gradually phase out a ten-print limit on the scale of theatrical releases, with a full liberalisation scheduled for 1994.

With the passage of these laws, what had formerly been one of the most regulated film markets in the non-Communist world was suddenly thrown open to foreign competition. Although local filmmakers had welcomed the deregulation of local production in the fifth revision, many were frightened that such a sudden market opening would overwhelm local industry. The film community first mobilised to campaign against the Korea-US Film Agreement, then lobbied for a delay so that the industry could find its feet before the full market opening. In the end, the government turned a blind eye to the petitions and rallies, and the reforms went ahead on schedule.

The one regulatory safeguard left in place at this time was a Screen Quota system that required all theatres in Korea to screen domestic films for a minimum number of days per year (106–146 days, depending on various factors). The aim of the quota was to ensure that local films received adequate screen time to reach their box-office potential. Although theatre owners opposed the system, since it obligated them to screen Korean films in place of higher-earning foreign titles, supporters argued that the quota was necessary to give local investors reassurance that the finished work would receive a reasonably-sized commercial release (see Yecies 2007). A decade later, the Screen Quota would re-emerge as a key point of contention between the Korean film industry and the MPEAA.

Changes wrought by the branch offices

The opening of branch offices by the Hollywood studios took place over a five-year period, beginning with UIP in March 1988, and followed by Twentieth Century Fox (August 1988), Warner Bros. (December 1989), Columbia Tristar (October 1990) and Buena Vista International/Disney (January 1993). Their presence in the Korean film market, together with the deregulation of film imports, would hasten the collapse of several aspects of the old system. In particular, the distribution sector – and by implication, the financing of Korean films – would never look the same again.

In previous decades, Korea’s distribution/financing system had evolved in ways that that were not particularly efficient, but which allowed for business risk to be shared among multiple parties. The major filmmaking companies were based in the capital Seoul, and each operated one major theatre in the city centre that acted as a primary source of revenue. For example, Taehung Pictures, which produced films by Im Kwon-taek, Jang Sun-woo and others, leased and operated Korea’s oldest theatre Danseongsa. The company would release the Korean films it produced, as well as any foreign titles it was allowed to import, in this venue and retain the profits from ticket sales. However Taehung did not distribute nationwide. South Korea was divided up into six other regional markets, based around the outer regions of Seoul, Gyeonggi/Gangwon, Chungcheong, Honam/Jeju, Gyeongbuk and Gyeongnam, which included Korea’s second largest city Busan. In each of these markets, a number of regional distributors (typically 5–7 per region) would book films into local theatres and arrange for marketing/publicity. For a typical release such as Lee Jang-ho’s Between the Knees, Taehung would pre-sell the film to a regional distributor in each market while the work was in pre-production. After gathering payment from the six regions, it would use this money to finance the film’s production. Subsequently, upon its theatrical release, the local distributors would keep the profits earned in each region (see Paquet 2005: 36).

The advantage of this system was that, from the Seoul-based producer’s point of view, films could be made for less money up front, and the regional distributors would share in the risk that the work would fail commercially. Another issue was that companies in Seoul had little recourse to check the accuracy of admission figures supplied by the regional distributors, whose murky and aggressive business dealings were the stuff of industry lore. While profit-sharing arrangements involved a real danger of being cheated, the pre-sell system (referred to derogatively by Korean commentators as ipdo-seonmae or the ‘pre-harvest sale of rice’) eliminated any need for transparency or trust.

However, after the passage of the fifth and sixth revisions, the old system quickly entered a period of upheaval. Firstly, the market became much more difficult to navigate for many of the regional distributors. In the past, virtually any of the foreign films allowed into the country could be expected to earn a decent return; however, after the deregulation of imports it became much more difficult to predict which films had a chance of success. At the same time, the number of local production and import companies expanded greatly, meaning that new business relationships and partnerships had to be established. By the late 1980s, many of the less savvy regional distributors were going out of business; for example the city of Gwangju saw its number of distributors shrink from six to three between 1987 and 1989 (see Jo 2005: 158–9).

The more fundamental challenge to the system was the gradual move towards nationwide distribution. The Hollywood branch offices had plenty of capital and were more interested in maximising their profits than in doling out risk. Nationwide distribution also potentially offered them more control over how their films would be marketed to audiences. As in other areas, UIP was the pioneer in this effort. Bypassing the regional distributors, UIP sought to establish direct and trustworthy business relationships with theatre owners across the country who would release their films. Although the process took longer than expected, by 1992 the company had assembled a nationwide distribution line made up of forty screens.

The other branch offices, for their part, tried out different sorts of partnerships and contracts with the older Seoul-based companies who were more experienced in distribution. One company in particular, Seoul Theatre, headed by Gwak Jeong-hwan, formed long-term partnerships with Warner Bros., Buena Vista and later Twentieth Century Fox, giving it an unmatched lineup of films that helped it to assemble its own strong nationwide distribution network. (In the mid-1990s, Seoul Theatre would form an alliance with Korean company Cinema Service, creating a powerful distributor that would eventually play a major role in local cinema’s commercial renaissance.)

Such developments in distribution edged the Korean film sector closer to international business norms; however, it was also pushing Korean cinema into crisis. The flood of imports meant that domestic films were facing much steeper competition. At the same time, the regional distributors who had served as an important source of finance for Korean cinema over previous decades were moving towards irrelevancy. Whereas in 1984, domestic films sold 16.9 million tickets for a 38.5% share of the market, by 1993 (despite the success of Sopyonje) they had sunk to a modern-day low of 7.7 million tickets and a 15.9% market share. The branch offices, for their part, saw their share of the local market increase dramatically from year to year. A quote by critic Kim Hwa from the 1993 Korean Cinema Yearbook captures the despair felt by many local filmmakers in this era:

The Korean film industry began the year 1992 without a single coin to inherit from the past, and in a state of self-examination, set off on a lonely battle for its existence. It was a year marked by grim determination and a lonely, desperate struggle for survival. (1993: 41)

Enter the ‘chaebol’

Since the 1960s, South Korea’s economy had been dominated by large, family-owned conglomerates known as chaebol. Sharing much in common with Japan’s prewar zaibatsu (the two words also come from the same Chinese root), the chaebol prospered thanks to close ties to the government and easy access to state-guaranteed loans. Although active in a bewildering array of fields, by the 1980s the conglomerates were shifting their focus from chemicals, defence and heavy industries to electronics and high tech. It was the chaebol’s emergence as manufacturers of videocassette recorders that would eventually lead them to the film industry.

Korea put its first domestically-produced VCR on the market in 1979; however, by the mid-1980s it was clear that a lack of software (that is, pre-recorded videotapes) was holding back sales. Three of the chaebol – Samsung, Daewoo and SKC – responded by launching their own video divisions in 1984. Initially, the three companies sourced much of their content through exclusive video distribution deals with Hollywood studios, whereby the studios would sell the rights for a fixed price and the chaebol would produce the tapes and keep whatever profits were made (theatrical distribution was handled separately). However, this arrangement, lucrative for the chaebol, came unwound after the establishment of the branch offices. In 1988, UIP launched its own video distribution arm under the name CIC. Other branch offices were slower to follow UIP’s lead, but by the early 1990s they had restructured their business partnerships with the chaebol so that the former would produce videos under their own label, and the chaebol would merely distribute to wholesalers for a small percentage of profits, typically 12–13% (see Hwang 2001: 81).

The chaebol, deprived of what had once been their greatest revenue source, instead had to compete with each other to secure rights to Korean productions, other foreign films or US titles that were not affiliated with a studio. Meanwhile, the video market as a whole entered a period of explosive growth from 1989–92. Total revenues from the rental market rose from 196 billion won in 1989 to 600 billion won (approximately $670 million) in 1992, while outright sales of videos (sell-through) rose from 40 billion won to 250 billion won ($280 million). Prices paid for video rights jumped accordingly, particularly for Korean films.

The ‘planned film’ Marriage Story (1992), partly financed by Samsung

It was a matter of calculation that led Samsung to invest in its first Korean feature. Kim Ui-seok’s Marriage Story (Gyeorhon iyagi, 1992), about a new generation couple whose marriage plunges into crisis as the wife’s career takes off, was produced on a budget of 600 million won ($670,000). Samsung invested 150 million won, or 25%, in return for video rights, while producer Ikyoung Films retained theatrical, television and other rights. By investing before the film was made, Samsung was taking on the risk that the film would turn out to be a commercial flop; however, it obtained video rights for significantly less than the going rate for completed films. Marriage Story then turned out to be the top grossing Korean film of the year with a massive 520,000 admissions in Seoul. In the wake of this success story, Daewoo (which had considered but ultimately declined to invest in Marriage Story) and other conglomerates quickly followed suit, so that by mid-decade virtually all of the top-grossing Korean films had a chaebol investor.

Meanwhile, the chaebol found capable partners in the new generation of producers who had moved into the film industry following the fifth revision of the Motion Picture Law. It is unlikely that workable partnerships could have been formed with the old guard of producers who had dominated the industry during military rule, given concerns over the latter’s trustworthiness and lack of fiscal transparency. Young, innovative and financially literate, the new producers were committed to making a new kind of film.

As time passed, the chaebol became more and more active in the film industry. After initially participating as partial investors, by 1995 they were providing 50% or 100% financing for many Korean films. Some examples of features that were 100% financed by the chaebol include Lee Min-yong’s A Hot Roof, Kim Sang-jin’s Take the Money and Run (Doneul gatgo twieora, 1995) and Lim Soon-rye’s Three Friends (Se chingu, 1996) by Samsung; Park Kwang-su’s A Single Spark and Lee Myung-Se’s Their Last Love Affair by Daewoo; Kim Tae-kyun’s The Adventures of Mrs. Park (Bakbonggon gachulsageon, 1996) by SKC; and Park Chul-soo’s Farewell My Darling by Jinro (see Jo 2005: 186–8). As majority investors, the chaebol were now controlling all rights to their films, from the theatrical release to international sales. This was a significant change, because rather than simply providing finance and handling the video release, the chaebol were now intimately involved in all aspects of a film’s commercial life span.

In this way, larger conglomerates started to expand into other sectors of the film business. Both Samsung and Daewoo built up nationwide distribution operations, which hastened even further the demise of the regional distributors. The two companies also leased, purchased or built theatres in Seoul and regional cities to operate themselves, and both were active in the cable television sector. The chaebol also formed strategic partnerships with young producers, which allowed the latter to launch and operate their own production companies. Examples include Uno Films (later renamed Sidus), Myung Films and Cinema Service with Samsung; Cine2000 with Daewoo; and Ahn’s World Productions with SKC.

Thus by mid-decade, the biggest chaebol shared much in common with their primary competitors, the Hollywood branch offices. They were vertically integrated businesses that had a hand in nearly all aspects of a film’s life cycle from investment and production to distribution, exhibition and ancillary markets like video and cable television. They used their considerable financial resources to give their product increased prominence in the marketplace, while at the same time attempting to shape and develop the film market as a whole. Their efforts to secure imported films for their lineup even led them to invest in the US. In early 1996 Samsung purchased a $60 million, 7.6% stake in New Regency, producer of Michael Mann’s Heat (1995), giving it access to all the mini-major’s films (see the Korea Motion Picture Promotion Corporation’s Korean Cinema Yearbook 1996: 223), while in 1995 Cheil Jedang’s new film division CJ Entertainment bought a $300 million, 11% founding stake in major studio DreamWorks (see Russell 2008).

The activities of the chaebol brought many changes to Korean cinema. One was a rise in film budgets, which was perhaps part intentional and part the natural result of an increased amount of capital in the industry. The average film cost roughly 500–600 million won to shoot in 1992, but by 1996 this had risen to 1.5–2 billion won. This was accompanied by a drop in the number of films produced in Korea each year, partly due to the difficulties faced by smaller, non-chaebol affiliated film companies. After producing about one hundred films a year from 1989 to 1992, the annual average fell to about sixty, where it would remain for the next decade.

The chaebol’s approach also magnified the importance of the local star system. Given their generally conservative approach to investing, many chaebol insisted on the casting of name stars in an effort to reduce risk. With top actors like Shim Eun-ha and Han Suk-kyu more in demand, salaries began to rise. From a creative standpoint, this also created a predisposition towards narratives that focused on one or two strong central characters rather than ensemble casts.

Although the chaebol would invest in many works by the better known auteurs of the Korean New Wave, they also showed a strong interest in genre cinema. The success of Marriage Story in 1992 inspired a string of further sex-war comedies, such as Kim Ui-seok’s follow-up That Woman, That Man (Geu yeoja, geu namja, 1993) and Kang Woo-suk’s How to Top My Wife (Manura jugigi, 1994). A large number of dramas about marriage and family, many starring the actress Choi Jin-sil, also appeared, including Mom’s Got a Lover (Eommaege aeini saenggyeosseoyo, 1995), Ghost Mama (Goseuteu mama, 1996) and Baby Sale (Beibi seil, 1997). Nonetheless, the chaebol’s film divisions were often criticised for taking an overly formulaic approach that failed to significantly diversify commercial Korean cinema.

Shin Chul and the ‘planned film’

One of the ways in which Korea’s young producers attempted to survive in the now highly competitive local market was to introduce new methods of developing and producing films. One of the most influential figures in this regard was Shin Chul, a member of the ‘cultural centre generation’ who, while overseeing marketing at the Piccadilly Theatre in Seoul in the mid-1980s, was able to meet and interview large numbers of ordinary viewers. This experience, which he called ‘eye-opening’, led him to push for a new model of commercial filmmaking that would incorporate a far more detailed knowledge of viewers’ perspectives and tastes into the screenwriting process. Observers would eventually refer to this type of work as the ‘planned film’ (gihoek yeonghwa).

The planned film involved the early identification of a target audience, the use of market research and a long period of script development and pre-production (none of which was widely practised at the time) to improve a film’s chances of success. An increased focus was also placed on marketing from the early stages of a project. The first feature to be labelled as a planned film was Kang Woo-suk’s Happiness Does Not Depend on School Records (Haengbogeun seongjeok suni anijanayo, 1989), starring Lee Mi-yeon as a high school girl at the top of her class who commits suicide due to pressure over grades. Shin’s company Shincine, launched in 1988 as a dedicated planning company, partnered with production house HwangKiSung Films on the project. Shin then interviewed over 500 high school students over a year-and-a-half and worked with screenwriter Kim Seong-hong to incorporate many of their ideas and experiences into the script. Shin describes how midway through development producer Hwang Ki-sung nearly pulled out of the project:

Hwang had originally liked the concept, but as time passed and no screenplay appeared (because we continued to rewrite it), he began to lose faith in it. The regional distributors were also telling him there was no demand for this type of film. I tried to persuade him to keep the project running, but he refused, so finally I picked ten of the high school kids we had interviewed and I asked Hwang simply to buy them dinner, and then I’d stop bothering him. He took them to a nearby pork restaurant and had a two-hour talk with them, and after it was done he came to me and said, ‘I think we need to make this movie.’ (Interview with author, November 2008)

The film was a commercial success, with over 155,000 Seoul admissions, and soon other companies began to give greater weight to planning. As Shin notes, the production system in use at that time placed the majority of responsibility on three figures: the director, the line producer who would oversee the shoot and the executive producer who would secure financing. In most cases, the director would have to assume responsibility for both the aesthetic quality and the commercial marketability of the final product. Under the new system, the individual who was given a ‘planning’ (gihoek) credit took on increased responsibility for developing the film’s commercial potential. ‘We were not working off any foreign models at the time, but eventually I realised that in standard filmmaking practice, this was basically the role of the producer,’ says Shin (interview with author, November 2008).

It was with Shincine’s next project, the aforementioned Marriage Story, that the planned film enjoyed its highest profile success. Targeting female viewers, Shin interviewed countless numbers of young married couples and employed eight screenwriters to perform 16 rewrites of the script. After the huge success of the project, Shincine began producing films on its own, rather than complement the work of other production companies. Its first in-house production, the Daewoo-financed Mister Mama (Miseuteo mama, 1992), about a husband left to raise his baby daughter after his wife runs off, was a solid hit with 230,000 Seoul admissions. The success of that work helped to establish two more companies: producer/director Kang Woo-suk launched Cinema Service, which would later evolve into a major studio, and co-producer Yu In-taek launched Keyweck-shidae (literally, ‘Age of Planning’), which would produce A Single Spark, Resurrection of the Little Match Girl and May 18 (Hwaryeohan hyuga, 2007). In general, Shincine’s early films are famous for gathering together figures who would eventually become the industry’s most powerful producers. Tcha Seung-jae, future head of Sidus FNH, served as production manager on Mister Mama; Shim Jae-myung (aka Jaime Shim), who would co-launch Myung Films and produce JSA, The Isle (Seom, 2000) and A Good Lawyer’s Wife (Baramnan gajok, 2003), oversaw marketing on Marriage Story; and Oh Jung-wan, who would launch b.o.m. Film Productions and produce Untold Scandal (Seukaendeul, 2003), A Bittersweet Life (Dalkomhan insaeng, 2005) and Night and Day (Bamgwa nat, 2007), was producer on Marriage Story.

Ultimately, the introduction of planned films can be seen as representing not just a reform of standard production methods, but also an effort to reconnect with mainstream viewers. Many of the films of the 1970s and 1980s were made with different audiences in mind. The ‘quality films’ of the 1970s, and many of the ‘quota quickies’ of the 1980s, were essentially made for government bureaucrats. Some critics charged that many of the period-set dramas of the 1980s were designed to appeal to international film festival programmers. The films of the Korean New Wave were ostensibly made for the minjung, but their formal experimentation and political orientation served to alienate many ordinary viewers. In this sense, not only the method but also the mindset behind planned films – perhaps best encapsulated by Shin’s anecdote about Hwang’s dinner with the students – was something new.

On the whole, local cinema continued to be held in low regard by most of the populace throughout the mid-1990s. In an effort to attract viewers, producers and directors experimented, attempting difficult-to-produce genres (period sci-fi epic The Gate of Destiny (Gwicheondo, 1996)), overseas locations (Inch’Allah (Insyalla, 1996), set in Algeria and shot in Morocco) or special effects (Shincine’s The Fox With Nine Tails (Gumiho, 1994), Korea’s first film to feature computer-generated imagery). Although many of these failed to turn a profit, they helped young producers gain experience and establish a foothold within the industry. On a technical level, young crew members improved their skills and learned from their mistakes. The Korean film industry had not enjoyed especially strong success in the early- to mid-1990s, but it had set the stage for a startling commercial revival that would arrive sooner than anyone expected.