The boom began with a crash. Confidence in the Korean economy had withered in the autumn of 1997, with the nation’s chaebol struggling under gargantuan levels of debt, banks weighed down by non-performing loans, and many individual companies (including, most prominently, carmakers Kia and Samsung Motors) facing bankruptcy. A full-blown financial crisis in Thailand over the summer had stoked fears that the contagion might spread across Asia and, sure enough, in November the Korean financial system experienced meltdown. The stock market plunged as it became clear that Korean banks were unable to pay back billions of dollars worth of short-term foreign debt, and that the government lacked the resources to rescue them. After several weeks of trying to hide the full extent of the problem, the Kim Young Sam administration announced on 22 November that, in order to avoid a default, it would ask the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a massive bailout.

The following months were a time of chaos. Ratings agency Moody’s downgraded Korea’s sovereign debt rating to junk status on 22 December. That same week, the Korean currency sank to an all-time low of 1640 won to the dollar, from 965 at the start of November. On 1 January, the government asked its citizens to donate gold and jewellry to help it repay its debts; according to organisers, ten tons of gold were collected in the first two days (Anon. 1998). Meanwhile the IMF, which had assembled the record $57 billion rescue package, attached strict conditions to the loans. Interest rates were pushed as high as 30%, causing many companies to go bankrupt, and the IMF dictated broad restructuring of the corporate and banking sectors, as well as changes to labour laws. Unemployment rose from 2.8% to 8.2% in less than a year. Some international economists would later criticise the IMF for prescribing overly harsh medicine that may have only made the situation worse.

As the crisis raged, Korea held its third presidential election of the democratic era on 18 December. After losing the previous two contests, opposition leader Kim Dae Jung prevailed, pulling out a narrow 39.7% victory in a three-way contest. Kim’s inauguration in February 1998 marked the first peaceful transfer of power between ruling and opposition parties in modern Korean history.

Thus began the ‘IMF era’, a time of wrenching economic pain and humiliation that put millions out of work and noticeably thinned the ranks of Korea’s middle class. An estimated 20,000 companies went bankrupt in 1998, and the nation’s economy shrank by 5.8% (see Robinson 2007: 173). Among the thirty largest chaebol, eleven would eventually collapse, including Daewoo in 1999 with $80 million in unpaid debt. A deep pessimism for Korea’s future prospects settled over the populace.

The financial crisis also proved to be the death knell for many of the chaebol’s film divisions. Feeling political and economic pressure to shed unneeded subsidiaries and focus on core businesses, SKC closed its video and film divisions in January 1998, followed by Daewoo in January 1999 and Samsung in May 1999. The IMF crisis had seemingly robbed the film industry of its biggest investors at one stroke. However, as Hwang Dong-mi notes, even before the crisis hit, rumours were circulating that many chaebol were planning an exit (2001: 29–30). Profits, both for traditional theatrical/video releases and for new windows like cable television, had failed to meet original expectations. Imports, which in the early years had provided the film divisions with their most stable source of revenue, had become less profitable after fierce competition between Korean buyers pushed up prices by 50%. The box-office failure of several big-budget productions like CJ Entertainment’s Inch’Allah, Daewoo’s Firebird (Bulse, 1997) and SKC’s Ivan the Mercenary (Yongbyeongiban, 1997) had caused many chaebol to switch from majority to minority investing in local films. Indeed, LG had already pulled out of the film industry in late 1996.

With the chaebol on their way out, only 43 local features were released in 1998, the lowest level since 1957. However, in contrast to the early 1990s, the mood in the film industry was cautiously buoyant. Optimists could point to several factors. For one, despite a slide in production, admissions to Korean films continued to rise. Boosted by hits such as Chang Youn-hyun’s Internet romance The Contact (Jeopsok, 1997) and Lee Jeong-guk’s melodrama The Letter (Pyeonji, 1997), which was enjoying a strong run in theatres even as the financial crisis was playing out, 59 local releases sold 12.1 million tickets in 1997 for a 25.5% market share. The following year, a mere 43 features sold 12.6 million tickets for a 25.1% share. Furthermore, a majority of the hit films in these years had secured financing not from the chaebol but from other sources, such as Kang Woo-suk’s Cinema Service or Ilshin Investment, the first venture capital company to invest in Korean film.

Secondly, when the Korean currency crashed, the comparative costs and merits of domestic and imported films suddenly shifted. For example, SKC had purchased Korean rights to the Hollywood film Seven Days in Tibet in early 1997 for $3.5 million. When the contract was signed, this was equivalent to 2.8 billion won, but at the time payment was due it took 5 billion won to purchase the same amount of dollars. Not surprisingly, many large and small Korean companies wasted no time in closing their film acquisition departments. Local films, in contrast, began to seem like a more stable investment. Although the cost of making them had not lowered, the average 1998 budget of 1.2 billion won ($900,000) before print and advertising fees began to look more reasonable compared to the cost of acquiring a foreign film, and investors had no need to worry about currency fluctuations. In addition, any export revenues the films earned would be worth more in local currency. Exports of Korean films were still rare in the late 1990s, but the figures were rising: The Gingko Bed (Eunhaengnamu chimdae, 1996), for example, earned $500,000 from sales to Hong Kong, China, Singapore and other Asian countries (see Nam 1997).

The age of debut directors: 1996–2000

The biggest grounds for optimism, however, lay in the content. By 1998 it was becoming clear that a younger generation of directors was bringing a distinctly new aesthetic to Korean cinema. Youth-oriented, genre-savvy, visually sophisticated and not ashamed of its commercial origins, the New Korean Cinema of the late 1990s was perceived by Korean audiences as being something entirely different from the works that preceded it.

Kim Jee-woon’s debut film, the horror-comedy The Quiet Family (1998)

The Quiet Family (Joyonghan gajok, 1998), the debut feature by director Kim Jee-woon, is a representative example of how the new films contrasted with the old. Set in a family-run lodge located alongside a hiking trail, the film focuses on the increasingly desperate actions of the owners when their lodgers keep turning up dead. Shifting back and forth between comedy, suspense and a dull sense of dread as the bodies pile up, the film exhibits a playful, carefree attitude at the same time as it shows how one act of violence can quickly lead to more. Meanwhile, a misprint on a signboard early in the film identifies the lodge as a ‘safe house’, a 1970s term referring to homes used by intelligence agents for interrogations and other secret operations. Film critic Kim Hyung-seok argues that, given this and other references, the eerie space of the lodge is meant to evoke the horrors of 1970s Korean politics (2008: 27–9).

On a visual level, The Quiet Family looked markedly different from its cinematic predecessors. Shot in rich, saturated colours, the film prioritised the use of lighting and set design to create memorable visual compositions rather than to capture the locale in any realistic manner. The opening shot, an exhilarating Steadicam sequence that meanders from the second floor down the stairs and onto the first before turning and retracing its steps, introduces the layout of the lodge but also clearly revels in its own technical bravado. If the visuals of the Korean New Wave functioned to ground the work in reality, the new directors were more likely to view visual expression in abstract terms, or as an end in itself.

Most notable about the film in the context of its time was its eclectic approach to genre. The Quiet Family’s casual appropriation and juxtaposition of genre conventions – from the lighting effects of horror to the broad physical movements of slapstick comedy – set it apart from both the commercial and art-house traditions of Korean filmmaking. Kim was not the only one practising such genre alchemy: in its wrap-up of the year 1998, film magazine Cine21 named ‘genre diffusion’ as the first of ten key issues that had defined the year (Anon. 1999). On one level, New Korean Cinema grew out of a sincere love for genre films of all sorts. And yet for directors such as Kim, genre remained an object to be manipulated rather than a model to be followed. The enigmatic and open-ended conclusion of The Quiet Family violates the conventions of both the horror and comedy genres. Kim was borrowing from genre cinema, but also felt comfortable in adopting a narrative structure that was closer to art-house cinema than to mainstream commercial filmmaking.

In short, the new directors were cinephiles. Having been active participants in the cinephile movement of the early- to mid-1990s, which encompassed a broad range of cinema from European auteurs to Hong Kong action films, Taiwanese art cinema and Hollywood B-movies, they were now ready to incorporate these influences into local films. Audiences, for their part, proved highly receptive to such an approach. The sudden spread of foreign cinema in domestic film culture a decade earlier had found its way back into Korean cinema.

Korean film critic Kim Young-jin has referred to the energy that animated this movement as ‘the adventurous spirit of children without fathers’ (2007b: ix). Compared to countries like France or Japan where a rich and well-preserved film heritage maintains a strong hold on the national imagination, in Korea local classics exerted only a weak influence at best. Younger generation filmmakers ‘are unable to claim affiliation to any lineage within film history, but at the same time they show a sponge-like resilience where they can assume whichever lineage suits them’, says Kim (ibid.).

This is not to say that older Korean films had no influence on the new generation. Major filmmakers including Bong Joon-ho and Park Chan-wook (who in this period was better known as a film critic writing in support of underappreciated B-movies and art-house works) have acknowledged a strong debt to the maverick Korean director Kim Ki-young, who under the military regime produced such brilliant classics as The Housemaid (Hanyeo, 1960), Insect Woman (Chungnyeo, 1972) and Iodo (1978). 1970s Korean genre films, including spy flicks and so-called ‘Manchurian Westerns’, would also influence directors such as Ryoo Seung-wan and Kim Jee-woon. However, the key point is that these directors approached these works as cinephiles in search of inspiration, and not as filmmakers struggling to find a place for themselves within a dominant national tradition.

Another quality that set the new directors apart from the previous generation was a sense of distance from the traumas of the 1980s. E J-yong (Yi Jae-yong), director of An Affair (Jeongsa, 1998), Asako in Ruby Shoes (Sunaebo, 2000) and Untold Scandal, touched on the difference between the two movements when he said, ‘Filmmakers from the 80s and 90s, like Park Kwang-su, Jang Sun-woo and Chung Ji-young, carry a great burden on their shoulders, in terms of history and politics. So they make very “heavy” films, and they can’t free themselves from the weight of their generation’s social issues. But directors in my generation feel free of such pressures. They pursue individual interests, rather than make films that speak for Korean society’ (in Paquet 2003). This is not to imply that the new directors did not take on socially relevant themes or revisit the events of recent history. Indeed, this was a vein that was mined often, and Kim Young-jin asserts that ‘though they might make films in a manner that appears playful, they also aim at a spirit of rebellion capable of provoking the group consciousness of the times’ (2007b: ix). Usually, however, the social concerns of new generation directors were concealed within a genre framework or else, like The Quiet Family, were presented to audiences in a veiled fashion.

The young directors of this era had chosen an auspicious time to make their debut. Given the troubled history of local films, and their long-standing weakness at the box office, producers gave young directors a clear mandate to break from the past and forge a new identity for Korean cinema. Particularly interested in targeting the large youth market (viewers in their mid-30s or above made up a comparatively small percentage of moviegoers), producers encouraged new themes and a diversification of subject matter, and proved generally willing to tolerate experimentation in form and genre. Given this atmosphere of creative licence, it is probably no coincidence that almost all of the biggest names in New Korean Cinema debuted within this five year period: Hong Sang-soo, Kim Ki-duk and Kang Je-gyu in 1996; Lee Chang-dong in 1997; Kim Jee-woon and Im Sang-soo in 1998; and Bong Joon-ho in 2000. In contrast, no Korean director who debuted between 1990 and 1995 would go on to build a major international career, with the exception of Park Chan-wook, who did not establish himself until his third feature Joint Security Area in 2000.

Changes in film education

Another development that led to a diversification of styles and approaches in New Korean Cinema was the spread of film schools in the 1990s. Previously, most directors received their training under an apprentice system that involved working as an assistant to a more established filmmaker before making one’s debut. Although several university-level film production departments existed in the 1970s and early 1980s (in 1980 there were four: Dongguk University, Chung-Ang University, Hanyang University and the Seoul Institute of the Arts), director Park Kwang-su explains that the curricula at such schools were focused on abstract and experimental film, and therefore graduates rarely, if ever, entered the mainstream film industry (interview with author, August 2008).

In 1984, the creation of the state-supported Korean Academy of Film Arts (KAFA), which offered a two-year programme in practical filmmaking skills, opened up a new path to joining the industry. The first graduating class included many future directors including Park Chong-won (Kuro Arirang) and Kim Ui-seok (Marriage Story). In the 1990s especially KAFA would emerge as the industry’s leading source of talent, with a list of alumni that includes Bong Joon-ho (Memories of Murder), Im Sang-soo (The President’s Last Bang), Hur Jin-ho (Christmas in August) (Palworui keuriseumaseu, 1998), Jang Joon-hwan (Save the Green Planet) (Jigureul jikyeora, 2003) and Choi Dong-hoon (Tazza: The High Rollers) (Tajja, 2006). The example set by KAFA also encouraged the opening of new university film programmes and the adoption of more practical-based approaches at existing departments. The number of film production departments at Korean universities stood at nine in 1989, 17 in 1996, 29 in 1999 and 52 in 2007 (see the Korean Film Council’s Korean Cinema Yearbook). One particularly influential programme would be in the film department at the Korean National University of Arts, which opened in 1995 and which would turn out directors such as Jeong Jae-eun (Take Care of My Cat) (Goyangireul butakae, 2001) and Na Hong-jin (The Chaser) (Chugyeokja, 2008). At the same time, an increasing number of young Korean directors went abroad to receive their training, including Hong Sang-soo at the Art Institute of Chicago, Song Il-gon and Moon Seung-wook at the Polish National Film School in Lodz and Min Boung-hun at the Russian State Institute of Cinematography (VGIK).

The shift from an apprentice-based system of film training to more formal education in film schools helped to create a higher level of technical expertise among debut directors and cinematographers. It also gave film school graduates the opportunity to showcase their talent through short films. Producers, as well as directors looking for capable assistants, began to attend short film festivals and public screenings of graduation films from KAFA or the Korean National University of Arts in order to scout talent. It was the steady production of new filmmaking talent that allowed Korea to turn out an eye-opening number of debut directors each year. Many producers displayed a preference for working with first-time directors, partly because of their lower salaries and partly because they were perceived as being more likely to compromise over the final cut, in an industry that traditionally granted the director strong creative control. The year 2002 was typical: of 59 major theatrical releases, 31 or 53% were by debut directors.

The new system also proved to be more open to women. Excluding documentaries, only three women made their debut in the commercial film industry in the 1990s: Lim Soon-rye with the critically acclaimed Three Friends in 1996, 301/302 scriptwriter Lee Seo-gun with Rub Love (Reobeureobeu) in 1997 and KAFA graduate Lee Jeong-hyang with the popular hit Art Museum by the Zoo (Misulgwanyeop dongmurwon) in 1998. However, from 2001 to 2007 no less than 22 female directors saw their feature debut receive a commercial release. The new system promoted diversity in other ways as well. Director E J-yong, whose KAFA graduation short Homo Videocus (co-directed with Daniel H. Byun) won awards at the Clermont-Ferrand and San Francisco film festivals in 1990, argues that he too would have been unlikely to make his debut under the old system, given producers’ propensity to favour extroverted, ‘macho’ personality types (in Paquet 2003).

The battle over the Screen Quota

Meanwhile controversy was brewing over Korea’s Screen Quota system. Although on the books in various forms since 1966 (for a detailed examination see Yecies 2007), the quota emerged as the film industry’s central protective measure against imported films in the mid-1980s, when other import barriers were removed. The system was designed to ensure that Korean films as a whole received a minimum amount of screening time in local theatres. Exhibitors were required to show domestic films on each screen for at least 30–40% of the year, or else face suspensions. Specifically, the base quota was set at 146 days per year (40%), but the Ministry of Culture and Tourism was at liberty to provide a reduction of twenty days each year (which it consistently granted), and each theatre could lower its individual quota by a further twenty days by screening local films during peak seasons, such as the summer and winter school vacations.

A Screen Quota protest in mid-1999 (Photo courtesy of Cine21)

As the audience for local films continued to shrink in the early 1990s, observers suspected that, with the culture ministry showing little inclination to enforce the measure, most theatres were not fulfilling their quota obligations. Taking matters into their own hands, in January 1993 film industry activists formed a group called the Screen Quota Watchers, which sent members out to major theatres each day to check in person which films were being screened. At the end of the year, the group announced that the average theatre had over-reported the extent to which it had screened Korean films by 48 days. In the coming years, the Screen Quota Watchers would use such statistics to publicise the issue and to pressure the government to enforce the measure. In 1994, the gap between the average theatre’s reported number of screening days for Korean films and the actual number was 51.7 days, followed by 37.6 days in 1996, 20.5 days in 1997, and 10.8 days in 1998 (Anon. 2001: 8; no figures published for 1995). This steady decline can be attributed to the Quota Watchers’ efforts, although the rising popularity of Korean cinema surely played a major role as well.

However, throughout this period Hollywood lobbyists, led by the MPA’s (formerly MPEAA) Jack Valenti, were pushing forcefully for the abolition of the Screen Quota. Arguing that the system was a violation of free trade principles, in 1998 US trade officials placed the quota on a list of items to be discussed in negotiations for a South Korea-US bilateral investment treaty. In July of that year, Korea’s trade minister indicated that the government was leaning towards abolishing the quota. Members of the film industry reacted at once, forming an emergency committee, holding press conferences and staging protests in front of theatres.

Then in November, Korean trade negotiators proposed a reduction of the quota to 92 days – which their US counterparts rejected, hoping for a full repeal. In response, filmmakers took to the streets for the first time in a decade. Close to one thousand actors, directors, crew members and students participated in a march through central Seoul on 1 December, while on the same day, a group of top producers began a series of sit-ins at Myeongdong Cathedral (epicentre of the 1987 pro-democracy movement) which would ultimately last more than two months. The protests received wide coverage in the local press, not the least due to the star power involved, and polls showed that the public sympathised with the filmmakers. A group of twenty citizens’ groups and NGOs also made public statements on behalf of the Screen Quota.

President Kim Dae Jung later announced his intention to keep the quota at its current level, which partially diffused the sense of crisis. However, in the coming months (and years), protests would continue at intervals as further announcements by various government figures seemed to hint at an imminent decision. The following June, in an even more photogenic display, 117 producers and directors including Im Kwon-taek and Kang Je-gyu shaved their heads in a rally held across the street from the US Embassy. Supporters of the quota, in keeping with similar cultural diversity movements across the globe, insisted that film as a cultural product should be excluded from trade negotiations. Demonstrators also argued (likely expecting it would never happen) that the quota should be kept at its current level until Korean cinema captured a 40% share of the local market.

The birth of the Korean blockbuster: Shiri and JSA

The projected image of Korean cinema in the Screen Quota protests was of a fragile, vulnerable industry. One of the most memorable photos from the December 1998 rally, reproduced on the cover of Cine21, was of actress Shim Eun-ha and other top stars dressed in black, carrying their own funeral portraits (an image that also recalled the critically acclaimed Christmas in August, released earlier that year). However, in February 1999 Korean cinema would present a very different image of itself to the world with the release of Kang Je-gyu’s action blockbuster Shiri (Swiri, 1998).

Depicting a face-off between South Korean intelligence agents and a renegade group of North Korean special forces who are plotting a terrorist attack in Seoul, Shiri quickly established itself as a must-see film: Korea’s first bona fide event movie since Sopyonje. It offered big-budget spectacle, special effects, star power (primarily in the casting of the lead from The Contact, Han Suk-kyu, though it also featured future stars Song Kang-ho, Choi Min-sik and Kim Yun-jin), and a politically resonant theme. Its box-office performance was unprecedented – the film vaulted over Sopyonje’s domestic record in 22 days and ended its four-month run with 6.21 million tickets sold nationwide (equivalent to $27.6 million). It had been made for 2.7 billion won ($2.3 million), which although high by the standards of the day would leave investors awash in profits.

Distributed by Samsung Entertainment as one of its final releases, Shiri featured shootouts on urban streets, exploding buildings, car chases, ticking bombs and other narrative/visual clichés of big-budget action films from Hollywood or Hong Kong. At the same time it incorporated a melodramatic love story between a South Korean agent and a North Korean spy that played off of Korea’s collective anxiety over its long-standing political division. The film borrowed liberally from the model of the Hollywood blockbuster, but in addressing Korean themes it sought to be recognised and accepted as a local work.

Here, perhaps, was the sort of product envisioned by Kim Young Sam after hearing the Jurassic Park/Hyundai cars presentation in 1994. Not only did it break records in Korea, but it secured a highest-ever sale to Japan for $1.3 million, and it performed well in commercial releases throughout Asia. Shiri had achieved blockbuster status not only through its style and content but in the way in which (helped by a wide release and an aggressive marketing campaign) it was experienced as a shared cultural/media event. Indeed, in future years the phenomenon surrounding Shiri’s release would remain far more discussed than the film itself.

Many also viewed the work as a political text. Although the North Korean special forces were depicted as ruthless killing machines, the film allowed viewers a glimpse into their perspective, most famously in a monologue delivered by Choi Min-sik (‘How can you, who grew up eating Coke and hamburgers, understand that your brothers in the North are starving?’), and in the sympathetic character of the undercover North Korean agent who infiltrates the South’s operations. To that date, Korean filmmakers had still not yet taken advantage of relaxed censorship to present rounded characters from modern-day North Korea. At a time when president Kim Dae Jung was moving forward with his ‘Sunshine Policy’ built on engagement with the North, the film came across as both timely and relevant. (Jang Jin’s The Spy (Gancheop richeoljin, 1999), released a month later, was also notable in this respect.)

In its cinematic style, marketing and its ultimate success Shiri left an unmistakable mark on Korean film history. Director Kang Je-gyu, who had already scored a box-office hit with The Gingko Bed in 1996, became recognised as one of the industry’s commercial titans (and he took this opportunity to launch his own production/distribution/exhibition company KangJeGyu Films). However, Shiri’s most lasting effect may have been to impart to the industry a sense of expanding possibilities and self-confidence. Projects that may have seemed overly risky or ambitious a year earlier began to be perceived as lying within reach.

Meanwhile, a second Korean blockbuster would emerge in September 2000. Directed by the little known critic/filmmaker Park Chan-wook, Joint Security Area (or JSA) structured its narrative around a shooting incident at the border between North and South Korea. After a Swiss investigator named Sophie Jean (Lee Young-ae) arrives to mediate between North and South and their conflicting reports of the incident, the film moves into an extended flashback which reveals that two Northern and two Southern soldiers had met in secret and formed a close friendship in the weeks leading up to the deadly shootings. With both sides throwing obstacles in her path, Jean soon realises that she is charged with uncovering a truth that neither side wants to acknowledge.

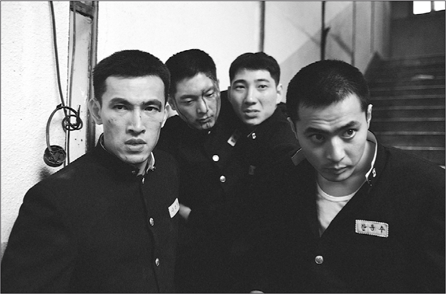

The blockbuster Joint Security Area (2000) launched the career of Park Chan-wook

Like Shiri, JSA featured a well-known cast (Song Kang-ho, Lee Byung-hun, Lee Young-ae), a large budget (3 billion won before print and advertising costs, close to one third of which was spent on a 90% replica of the border village Panmunjeom), and a politically timely theme centred on North-South relations. It also duplicated Shiri’s success at the box office, with 5.83 million tickets sold after four months on release. (In 1999, Shiri’s total admissions were calculated as 5.8 million, but in April 2001 KangJegyu Films revised its estimate of Shiri’s total to 6.2 million.) A flood of news stories covered every aspect of the film’s production and box-office performance, and the following February it was invited to screen in competition at the Berlin International Film Festival, where journalists drew comparisons to Germany and Berlin’s own history as divided entities.

If Shiri more obviously utilised Hollywood conventions to stage and explore Korea-specific themes, JSA (which was based on a bestselling novel) displays a wider range of influences in presenting its complex story. The narrative itself is structured as a mystery; however, Park himself refers to this as a ‘MacGuffin’ meant to temporarily distract viewers from the heart of the story (quoted in? Kim Young-jin 2007b: 80). By the time the mystery’s secret is revealed, it carries little emotional force because the characters have come to dominate the story.

Politically, JSA goes far beyond Shiri in humanising characters from the North. The nuanced acting of Song Kang-ho as Sergeant Oh and Shin Ha-kyun as Private Jung cause the viewer to forcefully identify with their characters, perhaps to an even greater extent than with the Southern soldiers. In doing so, the film creates a tension between the realm of the personal, in which the soldiers forge a close friendship, and the political, in which both sides remain sworn enemies. It is the seeming irreconcilability between these two realms that gives the film’s dramatic conclusion its potency. At the same time it inevitably leads viewers to question the existing political framework.

The makers of JSA benefited from fortuitous timing, in that just three months prior to the film’s release a historic summit took place in Pyongyang between South Korean president Kim Dae Jung and North Korean leader Kim Jong Il. The meeting represented the most dramatic warming in North-South relations in the two countries’ history, and raised hopes that more than four decades of open aggression might finally be nearing an end. Later developments would dash such hopes, but JSA arrived in theatres just as many South Koreans were rethinking their attitudes towards the North, and the film functioned as a site of reflection upon such issues.

Julian Stringer describes the word ‘blockbuster’ as ‘a moving target – its meaning is never fixed or clear, but changes according to who is speaking and what is being said’ (2003: 2). Although some general notions surrounding the blockbuster are enduring, such as their size in relation to other films, their positioning as ‘event movies’ and their use of spectacle, Stringer argues that they are best understood as a genre. In this sense they are subject to the same kinds of internal and external struggles as other genres over their defining characteristics and boundaries.

In Korea as well, the meaning of the term blockbuster (transliterated from English into Korean and adopted as a loan word) has evolved over time, especially when referring to local productions. The first domestic film to lay claim to the term ‘Korean-style blockbuster’ in its marketing was Park Kwang-choon’s The Soul Guardians (Toemarok) in 1998. Financed by Samsung, the film was based on a popular Internet novel about a young woman who had the ability to resurrect an evil supernatural force. Although notable for its advances in the field of computer-generated imagery (and many of the artists who rendered its CGI shots went on to found leading special effects companies in the coming years), the poorly-reviewed film fell short of expectations at the box office, and its marketers’ efforts to define the work as a new type of film failed.

It was with Shiri and JSA, both of which staked early claims to blockbuster status in their pre-release marketing, that the concept of the Korean blockbuster began to take shape. Chris Berry (2003) argues that in both South Korea and China, filmmakers have attempted to ‘de-Westernise’ the concept of the blockbuster. In Korea, this has manifested itself in efforts to produce local versions at the same time that competition with Hollywood and the controversy over the Screen Quota system have resulted in a heightened awareness of the qualities (and especially the ‘bigness’) of US blockbusters. Nonetheless, the reception of Korean blockbusters by critics, journalists and audiences has been highly ambivalent. Although it is clear that, as Berry asserts, ‘the blockbuster is no longer American owned’ (2003: 218) Korean filmmakers’ appropriation of the blockbuster model would remain a topic of intense debate in the coming decade.

Government support and film investment funds

During his campaign for president, Kim Dae Jung promised to give strong financial and regulatory support to the cultural industries. After being elected, he largely followed through on his pledge: the year 2000 marked the first time that culture accounted for more than 1% of the government’s total budget. In the realm of cinema, Kim initiated a vast overhaul and expansion of support policies, most notably with the launch of the Korean Film Council (KOFIC) and the government’s encouragement of, and participation in, specialised film investment funds. In the next few years, South Korean support of the film industry would grow to vastly exceed that of any other Asian country.

In previous decades, the government body responsible for carrying out film policy was the Korean Motion Picture Promotion Corporation (KMPPC). Launched in 1973, the KMPPC oversaw a handful of programmes to support local filmmakers; one example was the ‘Good Films’ competition, launched in the 1980s, in which cash awards were presented to the ten best films of the year, as chosen by a group of journalists and critics. Under the Kim Young Sam administration, the body instituted a loan programme for selected film projects: 17 loans totalling 2.88 billion won in 1994, eleven loans totalling 1.85 billion won in 1995 and 14 loans totalling 2.72 billion won in 1996 (see Yi 2005: 412). More significantly, in November 1997 the KMPPC opened the Seoul Studio Complex (later renamed the Namyangju Studio Complex), which provided filmmakers with professional quality soundstages, recording facilities and other amenities for the first time in decades.

After Kim Dae Jung took office, the KMPPC was restructured as a civilian-run organisation and relaunched in May 1999 as the Korean Film Council. The new body received its funding from the Ministry of Culture and Tourism but was largely independent in drafting and carrying out the nation’s film policies. It was headed by a group of ten commissioners, including filmmakers, professors and other figures from the film industry, with one among them chosen as a full-time chair. Its funding was also boosted: by its second year, in 2000, KOFIC’s total budget of 69.5 billion won ($61 million) was more than double the highest amount granted to the KMPPC under Kim Young Sam.

Nonetheless, in the first year of its existence KOFIC was witness to an intense power struggle between the film industry’s older generation, headed by veteran actress Kim Ji-mi who was serving as a KOFIC commissioner, and younger generation producers and directors who had entered the film industry in the late 1980s. Sharp disagreements arose over the allocation of support funds, culminating in public denunciations, lawsuits and the mass resignation of seven of the ten commissioners. Finally, the government sided with the younger members of the film industry, who assumed control of KOFIC and embarked on a decisive overhaul of Korea’s film policies. The successful efforts of younger generation filmmakers to gain control over the drafting of film policy stands as an important milestone in the development of New Korean Cinema.

Support programmes initiated in those years were various, including the first ever grants for short and independent films, the creation of regional media centres (‘MediACT’) to provide education and equipment rental to amateur filmmakers, production support for art-house and low-budget feature films, loans to commercial feature film projects, support for digital films, the production of subtitled prints of selected features and shorts, an expansion of KOFIC’s in-house research division, loans and grants to theatres specialising in art-house cinema, and more (See Davis & Yeh 2008: 21–4).

However, one of the most lasting initiatives of the Kim Dae Jung era was KOFIC’s active support of specialised investment funds. In partnership with the state-run Small Business Corporation (SBC), with which it had signed a cooperation agreement in 1998, KOFIC turned to Korea’s growing venture capital sector to enlist investors in five- to six-year funds that would devote 50–70% of their capital to film financing. By investing in a slate of films, rather than individual titles, it was hoped that risk could be lessened and spread among the fund’s various participants. To sweeten the pot, both KOFIC and the SBC agreed to participate themselves, with the latter taking on a greater share of losses should the funds fail to turn a profit.

From 1998 to the end of 2005, the film industry witnessed the launch of 48 funds worth a combined $535 million. Of this total the SBC contributed $121 million and KOFIC $46 million (see Paquet 2007a). Such efforts played a major role in the expansion and diversification of Korea’s film finance sector, with venture capital companies (both independently and in the funds described above) emerging as the film industry’s most active investors.

Friend, nostalgia and the new male hero

Julian Stringer notes: ‘Some movies are born blockbusters; some achieve blockbuster status; some have blockbuster status thrust upon them’ (2003: 10). Kwak Kyung-taek’s Friend (Chingu, 2001) ranks in the final category. Based on the director’s own experiences, the film centres around four high school boys whose bonds remain unshakable as they pass through adolescence: hanging out at the roller skating rink, fighting students from rival high schools, dealing with broken families, abusive teachers and economic hardship. Later in life, however, two of the men join rival gangs and the group is torn apart. Released in March 2001, the modestly budgeted film stunned observers by soaring past Shiri and JSA’s totals to record 8.2 million admissions (worth $37.6 million at 2001 exchange rates). Friend seemed to contain few of the standard building materials of a blockbuster. Although lead actor Jang Dong-gun would later be recognised as one of the industry’s biggest stars, at the time of Friend’s release he was not considered an unusually strong box-office draw. Likewise, director Kwak, a New York University graduate, was considered a dubious box-office prospect after the flop of his first two films, 3PM Bathhouse Paradise (Eoksutang, 1996) and Dr. K (Dakteokei, 1999).

The 1980s re-imagined in the smash hit Friend (2001)

Friend nonetheless introduced two novel elements to Korean cinema, one of which was a richly detailed portrait of Korea’s second city Busan. Although the city of 3.7 million had formed the backdrop to other recent films such as firefighting drama Libera Me (Ribera me, 2000), Friend was the first to highlight and even revel in the city’s distinctive regional character. This was done visually, with evocative portraits of Busan’s crowded streets and fish markets, but even more so linguistically, with a heavy but authentic-feeling use of local dialect and slang. Several memorable lines of dialogue, made up of words that many Koreans were hearing for the first time, became catchphrases in the wake of the film’s success. From this point on the highlighting of South Korea’s many distinctive dialects became a common feature in many Korean films, particularly comedies.

Friend also stands as one of the first Korean films to recast the experiences of the 1970s and 1980s in a personal and highly nostalgic light. After the Korean New Wave drew to a close in 1996 with the release of A Petal, some time passed before directors showed an interest in revisiting the politically charged decades of the 1970s and 1980s (Lee Chang-dong’s anguished Peppermint Candy being one notable exception). When at last they did, it was through coming-of-age films and nostalgic personal recollections of the era. Romantic comedy Ditto (Donggam, 2000), scripted by well-known playwright/film director Jang Jin, was the first in this lineage, depicting a time-warp HAM radio correspondence between a woman living in 1979 and a man living in 1999. Although the juxtaposition of the two eras highlighted their political differences, the portrayal of the earlier period was marked by strong overtones of nostalgia.

The first half of Friend reconstructed as well as de-politicised the early 1980s. The use of pop music (Robert Palmer’s ‘Bad Case of Loving You’), iconic imagery of the era (shots of the fumigation truck that accompany the opening credits) and universal tropes of adolescence (teen romance, fistfights) induced viewers to recall their own youth. Being such a phenomenal success, Friend helped to kick off a trend of 1980s youth films, with other examples including My Nike (Mutjima paemilli, 2002), Bet on My Disco (Haejeok diseuko wang doeda, 2002), Conduct Zero (Pumhaengjero, 2002), Mr. Gam’s Victory (Syupeoseuta gamsayong, 2004) and Bravo My Life (Saranghae malsunssi, 2005). Virtually all such films highlighted the relative poverty of the earlier era, and some proved more willing than others to reference political issues, directly or indirectly.

Korean filmmakers’ depictions of the 1980s only underscored how much Korean cinema had changed since that time. On a different level, this ever-widening gap also manifested itself in the characterisations of film protagonists. In his groundbreaking book The Remasculinization of Korean Cinema, Kyung Hyun Kim (2004) argues that while portrayals of women in Korean cinema did not undergo a fundamental change between the 1980s and the present, depictions of men went through a noticeable transformation. The traumas of the 1970s and 1980s, and ordinary citizens’ powerlessness in the face of authoritarian rule, were reflected in 1980s cinema in a pervading sense of threatened masculinity. The typical male hero of that era, such as the thin, shy college student Byeong-tae from Bae Chang-ho’s smash hit Whale Hunting, was characterised by his lack of power, and solicited viewer identification and pity. Such depictions served as a critique and counterpoint to the highly masculinised strain of nationalism pushed by the military regime, though Kim argues that in structuring many narratives around the quest and ultimate attainment of masculine power, such films ended up reaffirming the status quo. Other male protagonists, from the angry young men of Fine Windy Day and Chilsu and Mansu, to the intellectual writers in White Badge, To You, From Me and A Single Spark, also grapple with the aftermath of trauma and seek release from anxiety.

The industrialised, global age of the early 2000s produced a new kind of male hero, as epitomised by the sleek, muscled protagonists of Friend played by Jang Dong-gun and Yoo Oh-sung. Freed of anxiety and fear, the self-confident, articulate men of New Korean Cinema emerged as objects of desire. And yet there also lay within these characterisations a new capacity for aggression and sadism. Such idealised heroes were, in Kim’s words, ‘confidently violent’ (2004: 232).

High concept comedies and the 50% market share

With the triumphant success of Shiri, JSA and then Friend, venture capital companies were soon clamouring for more big-budget, genre orientated projects in which to invest. However, the next few years would not be kind to the Korean blockbuster. A string of expensive genre films including futuristic action movie Yesterday (Yeseuteotei, 2002), family adventure R U Ready? (A yu redi?, 2002), subway-set action film Tube (Tyubeu, 2003), science fiction feature Natural City (Naechyureol siti, 2003) and most spectacularly Jang Sun-woo’s fascinating but commercially disastrous cyber action film Resurrection of the Little Match Girl all flopped at the box office, putting their investors deeply into debt. Such titles were marketed on the basis of their genre credentials, high budgets and advanced special effects. Nonetheless, they were not as localised as Shiri and JSA, which, in retrospect, may have contributed to their undoing: all of the above films lacked A-list stars and did not engage significantly with local issues. Notably, the one commercially successful (if critically lambasted) blockbuster of 2002, sci-fi action film 2009 Lost Memories (2009 roseuteu memorijeu, 2002), featured top star Jang Dong-gun and a plot focused on Japanese-Korean relations. Set in an alternate future, it imagined that Korea had remained a colony of Japan into the early twenty-first century.

Meanwhile, another kind of film was rapidly gaining popularity among viewers. The high concept comedy, targeted at youth audiences and featuring an easy to describe central premise, had been gaining momentum since the breakout hit Attack the Gas Station! (Juyuso seupgyeok sageon) in 1999. Directed by Kim Sang-jin, the film depicted four rowdy young hooligans who rob a gas station and, finding no money in the cash register, decide to take the staff hostage and pump gas all night, keeping the proceeds for themselves (‘This is a cash and full-tank only day’, they inform puzzled customers). Shot on a single set, the film draws its laughs from the way that power relations shift among the various characters who show up on that chaotic night. Key to the film’s sensibility is the reason given by the four protagonists for robbing the station in the first place: ‘geunyang’, translatable as ‘just because’ or ‘just for the hell of it’.

Nancy Abelmann and Jung-ah Choi (2005) argue that the word geunyang in this context works as a rejection of coherent narration, in keeping with the film’s romanticised anti-establishment attitude – but is also linked to broader social transformations in the 1990s. Under authoritarian rule, South Korea had been dominated by grand narratives (‘development’ and ‘anti-communism’ at one end of the political spectrum; at the other, ‘anti-state activism’), which demanded subordination of the personal for the greater good. In the 1990s, grand narratives began to lose much of their pull, and a backlash arose against this type of collective logic. The carefree, self-directed and somewhat callous attitude behind the word geunyang was thus ‘emblematic of changed times’ (2005: 134).

A similar mindset underwrites the most popular sub-genre to emerge in the early 2000s: the gangster comedy. Although the influential No. 3 (Neombeo 3, 1997) served as an important model, the gangster comedy came into its own in the second half of 2001 with a string of runaway hits including Kick the Moon (Sillaui dalbam) (4.4 million nationwide admissions), My Wife Is a Gangster (Jopong manura) (5.2 million), Hi Dharma (Dalmaya nolja) (3.7 million) and My Boss, My Hero (Dusabuilche) (3.3 million). Whereas Friend had portrayed the world of organised crime in a sombre and almost reverential light, the gangsters who populate the comedies display a pugnacious, self-centred impudence that becomes an open target for ridicule. Needless to say, they feel no compulsion to subordinate the personal for the greater good – quite the opposite. However, the directors of these films often juxtapose the behaviour of the gangsters with that of authority figures in Korean society. In Kim Sang-jin’s Kick the Moon, a gangster and a high school physical education teacher compete for the attentions of a beautiful woman, and in the process the teacher is shown to be the more thug-like personality. In My Boss, My Hero, a dim-witted middle-ranking gangster is sent back to high school by his boss to earn his diploma; however, he soon discovers that the school administration is corrupt on a grand scale, leading to an ironic final showdown between school officials and organised criminals who fight to restore fairness to the educational system. In Hi Dharma, a group of gangsters forced into hiding demand refuge at a remote Buddhist monastery. This time it is the monks who set the moral example for the gangsters, but not before the former prove to be just as skilled at fighting as the latter.

The most commercially successful film of the group was Jo Hyun-jin’s My Wife Is a Gangster, starring actress Shin Eun-kyung as a ruthless crime boss who is persuaded by her terminally ill sister to find a husband. Eventually settling on a naive government clerk who suspects nothing about her true profession, she marries and continues her criminal activities in secret until an unexpected pregnancy ensues. Juxtaposing middle-class family life and the more sensational life of a gang leader, the film undercuts stereotypes and traditional gender roles in a teasingly provocative manner before (continuing a long tradition in Korean comedy) reasserting patriarchal values in its final reel.

The runaway success of Friend and the gangster comedy helped Korean cinema to capture an unprecedented 50.1% market share in 2001. Three years earlier, even a 40% market share had seemed impossibly out of reach, so this achievement had a profound psychological effect on the industry.

Significantly, producers had found box-office success with not one but several different filmmaking models. Film magazine Cine21 observed that the more commercial projects that were driving the development of New Korean Cinema fell into three broad categories. The first, the producer-orientated project, including the high concept comedies mentioned above, were typically built around a catchy central premise and shot with mid-level stars. Less expensive than the other two categories, they cost an average of $2 million to produce and were shot in three to four months. Other prominent examples include Sex Is Zero (Saekjeuksigong, 2002), a sex comedy set in a university, and Marrying the Mafia (Gamunui yeonggwang, 2002), about a gangster family who plot to marry off their daughter to a young lawyer.

In contrast, director-orientated projects were built around a well-developed screenplay and a director’s authorial style. More expensive to make ($3 million on average), they employed highly experienced crew members and big-name stars, who often preferred working on projects that tested their acting abilities. Director-orientated projects included infidelity drama Happy End (Haepi endeu, 1999) and Park Chan-wook’s follow-up to JSA, Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (Boksuneun naui geot, 2002). The third category was the Korean blockbuster, which cost about $6 million to make, much of it spent on mise-en-scène and special effects. As noted above, at this time many producers felt that A-list stars would not be necessary to attract viewers, who would instead be drawn by the film’s effects and technical qualities. In later years, however, stars would come to be seen as an essential part of the blockbuster package.

Throughout the commercial boom years of 1999 to 2006, each of these three commercial models would experience rises and falls in fortune. In 2001 and 2002, Korean critics began to lament the success of producer-orientated projects at the expense of director-orientated cinema, and worried aloud that investors would shift the vast majority of their funds to the former. However, as noted in the next chapter, director-orientated projects staged an eye-opening commercial comeback in 2003, just as high concept comedies began to struggle. Similarly, many pundits were ready to announce the death of the Korean blockbuster in 2003, but later events would prove them wrong. The unpredictable nature of viewers’ tastes in the first decade of the twenty-first century went a long way towards ensuring that no one model of production became dominant, with positive results for the overall diversity of Korean cinema.

Meanwhile, dramatic developments in commercial film did not mean that auteur cinema was dead. Some of the names best associated with New Korean Cinema occupy a space that is partially removed and partially connected with the movement’s dominant trends. One hesitates to distinguish unilaterally between art-house and commercial cinema in any aesthetic or qualitative sense, since on closer analysis such distinctions usually rest on unstable foundations. It is also worth noting that art-house films sometimes have real box-office clout: Oasis (Oasiseu), the third film by director Lee Chang-dong, spent three weeks at number one at the box office in autumn 2002. However, the works of Hong Sang-soo, Lee Chang-dong and Kim Ki-duk, among many others, spring from a different model of production from those described above, and given the strong individual character of their films they will be considered separately below.

New auteurs: Hong Sang-soo

The debut of Hong Sang-soo in May 1996 with The Day a Pig Fell into the Well (Dwaejiga umure ppajin nal) was, as described in film magazine Cine21, ‘a gunshot that shook Korean film history’ (quoted in Huh 2007a: 3). Told in four segments, each focusing on a different character (a frustrated novelist, his married lover, her timid husband and a ticket vendor in love with the novelist), the film was made of languid, everyday scenes but it was the manner in which they were shot and presented that drew notice. On one level, Hong’s sensitivity to behaviour and gift for language imparted to even the simplest exchanges between characters a vivid (or, perhaps, an enhanced) realism. At the same time the camera’s objective viewpoint and the director’s refusal to emphasise any one aspect of the image or story over another left viewers labouring to construct meaning out of what they saw. Finally, and somewhat surprisingly, when viewers stepped back to consider the film as a whole they discovered a complex interlocking structure in which details and lines of dialogue from one part of the film, which may have initially seemed unimportant, echoed and reinforced those from another. According to film critic Huh Moonyung, ‘The cinematic language spoken in this film was unprecedented in Korean film history. Korean movie critics thought of names like Robert Bresson and Luis Buñuel, but they agonised over the genealogy of a movie that was completely unique’ (2007a: 3). Hong’s cinematic style would emerge in clearer terms in his subsequent films, yet in some ways the puzzle remained. Although not granted the international recognition of Asia’s most famous auteurs, his works display a level of originality that demand, and sometimes elude, explanation.

David Bordwell argues that Hong’s films fit broadly into the minimalist tradition taken up by Asian filmmakers such as Hou Hsiao-hsien, Tsai Ming-liang and Kore-eda Hirokazu, in adopting episodic rather than goal-orientated narratives; in focusing on mundane, everyday occurrences; and in omitting important scenes or background information, leaving viewers unsure about characters’ motivations. Visually as well, Hong shares with Asian minimalist films an austerity in camerawork that forces the viewer to focus on small details. However, Bordwell argues that Hong ‘has developed a strikingly original approach to overall narrative architecture’ (2007: 22).

Hong’s first three films in particular adopt an almost geometric approach to narrative. The Power of Kangwon Province (Gangwondoui him, 1998), structured in two major parts, initially focuses on Jisuk (Oh Yoon-hong), a woman who travels to the east coast of Korea with her friends after breaking up with a married university instructor named Sang-gwon (Baek Jong-hak). The second part centres on Sang-gwon, who, without realising it and unbeknownst to Jisuk, takes the same train to Kangwon Province and passes time in the same locations, though they never meet. Hong, who in interviews has referred to this story of separated lovers as a (2-1)+(2-1)=2 structure (quoted in Huh 2007b: 54), complicates the relationship by playing with time (for example, by showing Jisuk erasing some graffiti off a wall, and then later in the film presenting the scene when Sang-gwon wrote it), and by withholding information so that we do not realise that Sang-gwon is Jisuk’s former lover until the film’s final reel.

The relationship between two major narrative segments is even more complex in Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (O! sujeong, 2000). This film, shot in black-and-white, juxtaposes two extended flashbacks: one seemingly based on the memories or perspective of Jae-hun (Jung Bo-seok), a wealthy single man; and another on the perspective of Su-jeong (Lee Eun-ju), who meets him by chance and gradually acquiesces to his sexual advances. Significantly, the two flashbacks often overlap so that we see the same scene presented twice, each time subtly different. The personality of each character also varies in each segment, filtered through the lenses of selective memory and ego. And yet the segments are not shot strictly according to point of view: some of the scenes presented could not have been witnessed by the character in question, and ultimately the nature of the flashbacks remains unclear. Hong also includes three scenes that take place in the present, placed at the beginning, the middle and the end of the film.

Beginning with his fourth film Turning Gate (Saenghwarui balkkyeon, 2002) Hong’s narratives have followed more familiar, chronological patterns of development. Yet they remain just as complex, with their echoes and repetitions expressed in the work’s details, rather than unusual narrative structures. Astute viewers may also notice links between different films. As Bordwell notes, ‘the later films tease us with the possibility that at any moment we will swerve into an echo chamber’ (2007: 28).

Hong, who studied at the California College of Arts and Crafts and the Art Institute of Chicago, has adopted an unusual approach to shooting that favours intuition and on-site inspiration over planning out scenes in advance. Working from a detailed treatment rather than a script, he writes out the dialogue for each scene on the set, on the morning of the day it is to be shot. Similarly, camera placement and angles are decided not in advance but on the set in consultation with the cinematographer. Hong works closely with his cast in developing each character, yet at the moment of shooting he does not solicit improvisation, giving his actors very precise instructions down to the smallest details and inflections.

This may account for the fact that the complex patterns that emerge in his works seem to replicate psychological rather than abstract or physical structures. Hong claims that vague feelings or unconscious preferences serve as the basis for many of the elements in his films. He explains: ‘I do calculate, but the decisions are made by intuition. It is easy to calculate once the structure is set. It’s intuition that decides where to draw the line’ (quoted in Huh 2007b: 59).

A suicide initiates a travel back through 20 years of Korean history in Lee Chang-dong’s Peppermint Candy (2000)

New auteurs: Lee Chang-dong

As the world celebrated on the night of 31 December 1999, die-hard Korean cinephiles marked the start of the new millennium in a different way. As the clock struck midnight, Lee Chang-dong’s second film Peppermint Candy officially launched its commercial release with a late-night screening. Although far from celebratory in its content, the film was nonetheless a fitting observation of Korea’s move into the twenty-first century.

Inspired by the Harold Pinter play Betrayal (1978), Lee’s film is told in reverse chronological order, progressing backwards through the life of its protagonist, but also (in both symbolic and literal fashion) revisiting two decades in recent Korean history. The first chapter, titled ‘Outdoor Excursion, 1999’, introduces us to the protagonist Yeong-ho (Sul Kyung-gu), a man in a crumpled suit who turns up unexpectedly at a riverside reunion of former factory workers. Yeong-ho frightens everyone with his crazed and erratic behaviour, then clambers up onto a railroad bridge. One concerned man pleads with him to come down, but Yeong-ho throws himself in front of an oncoming train, shouting, ‘I want to go back!’ – a phrase that will resonate throughout the film. The next chapter takes place three days before the suicide, with Yeong-ho buying a gun and then visiting a hospital to see a woman in a coma. Chapter three presents Yeong-ho as a small business owner in summer 1994, though we know from a line of dialogue in the previous chapter that his venture will end in financial ruin. Chapter four shows him as a police detective torturing student dissidents in spring 1987; a scene where he dunks a man’s head in the water recalls the death of Park Jong-cheol, which helped spark the massive protests that year. In chapter five, set in autumn 1984, he is a new recruit to the police force. Chapter six sees him as a military conscript in May 1980, when he finds himself sent with his fellow soldiers on an assignment to Gwangju to suppress the popular uprising. The final chapter depicts a picnic in autumn 1979 alongside the same river which opened the film. Meanwhile, in between each chapter is a brief insert, shot from the perspective of a running train and presented in reverse – the receding figures suggest a trip backwards in time.

As noted by Hye Seung Chung and David Scott Diffrient (2007), Peppermint Candy’s unusual narrative structure derives its power from the contrast between the implied chronological chain of events (the story, or in Russian formalist terms the fabula – progressing from 1979 to 1999), and the arrangement of the story in cinematic time (the plot or syuzhet, moving from 1999 to 1979). As a result, many of the objects, actions or lines of dialogue encountered in the film – such as a camera which seems to make Yeong-ho uncomfortable, the comment ‘life is beautiful’ and a jar of peppermint candies – appear initially to the viewer as riddles or enigmas, before they are given deeper meaning in subsequent chapters. Chung and Diffrient contend that the ultimate effect of this is not the shock of surprise we associate with the revelation of mysteries, but a sense of bitter irony. In this film, knowledge of the future only makes the past more painful to watch.

Now canonised as a modern classic, Peppermint Candy confirmed the promise shown by Lee in his debut film Green Fish (Chorogmulgogi, 1997), about a man in a quickly developing suburb of Seoul who seeks employment and purpose in organised crime. As a director Lee has become known for confronting sensitive topics in an austere, rigorous manner. He says, ‘Some audiences complain that my films are so tightly knit together and intentional that there is no place for them to escape. I admit this is true, but I don’t think it’s something I should avoid. If a film is to capture an audience, then [having] no way of escape is a virtue’ (quoted in Kim Young-jin 2007a: 66). His third film Oasis, which won a best director award at the Venice Film Festival, depicts a love affair between an ex-convict, Jong-du (Sul Kyung-gu) and Gong-ju (Moon So-ri), a woman with severe cerebral palsy. In its form, the film resembled a traditional melodrama, with two lovers struggling to maintain their relationship in a hostile world, but Lee’s austere style denied viewers any usual sense of emotional release. Although less epic in scope than Peppermint Candy, Oasis ranks as one of his strongest works, never romanticising the protagonists’ plight but depicting the neglect and discrimination they receive with a sober intensity. The outstanding, absolutely convincing performances Lee coaxed from his lead actors Sul and Moon were particularly notable.

Lee, who began his career as a successful novelist, took an unusual detour in early 2003. At the request of newly elected president Roh Moo Hyun, he took up the position of Minister of Culture and Tourism – the first film director in Korea ever to do so. His appointment was greeted with wide expectation, though ultimately his ambition to bring about lasting change in the nation’s cultural policies would become mired in political deadlock. Lee’s return to filmmaking after his resignation in mid-2004 was Secret Sunshine (Miryang, 2007), based on a short story about a woman who turns to religion after her son is kidnapped. The acclaimed work was invited to the Cannes Film Festival where the film’s lead, Jeon Do-yeon, one of Korea’s most talented performers, was presented with a Best Actress award for her performance. Lee’s bleakest and most emotionally devastating film to date, Secret Sunshine appears at first to be taking aim at the excesses of Korean Christian groups, but it ultimately becomes more focused on abstract, philosophical questions (and Lee himself denies any anti-religious agenda). The film is in some ways like a twenty-first-century, cinematic version of a Matthew Arnold poem, pondering the emptiness of a world where religion has lost its legitimacy. However, while the beauty of Arnold’s language and imagery act as a kind of salve to his readers, Lee’s tightly-bound filmic style offers no such consolation.

New auteurs: Kim Ki-duk

Director Kim Ki-duk entered the industry as an outsider, and although he has been supported in his rise to prominence by the Pusan International Film Festival, the Korean Film Council and local distributors/investors such as Sponge Entertainment, he remains in many ways removed from dominant trends in Korean cinema. Born in 1960 in the village of Bonghwa in North Gyeongsang Province, Kim dropped out of high school and spent his twenties serving in the marines, working in factories and volunteering at a church for the visually impaired. Having long pursued painting as a hobby, in 1990 he flew to Paris and spent two years selling his paintings on the street. Kim says it was at this time that he went to a movie theatre for the first time in his life.

After returning to Korea, Kim won a government-sponsored screenplay contest and then made his debut with Crocodile (Ageo, 1996), a crudely directed but visually inventive film about a man who fishes the bodies of suicides out of the Han River in Seoul and holds them for ransom. The director’s early works, including the Paris-set Wild Animals (Yasaengdongmul bohoguyeok, 1997) and Birdcage Inn (Paran daemun, 1998), focus on marginalised characters at the bottom of the social ladder, of a completely different sort than those evoked by the term minjung: pimps, low-ranking gangsters, prostitutes. Imbued with strong violence and a predatory sexuality, Kim’s narratives displayed a visceral feel for cruelty and class conflict. Cédric Lagandré observes: ‘People don’t talk to each other in Kim Ki-duk’s films, people hit each other. Relationships are always frontal, direct, decoded, never mediated through language which would neutralise the violence and allow individualities to meet in the neutrality of a shared space’ (2006: 60). Neither local viewers nor critics warmed to Kim’s early films. Feminists in particular were enraged at the lack of agency granted to female characters in his films, calling him a ‘monster’, a ‘psycho’ and a ‘good-for-nothing filmmaker’ (quoted in Lee 2001).

Controversy surrounds several of his best-known works from this period. The Isle (2000) takes place on a remote lake dotted with floating cabins where lodgers sleep, fish and buy sex from the reclusive woman, Hee-jin (Suh Jung), who serves them. One of her customers, Hyun-shik (Kim Yu-seok) is on the run from the police after killing his lover. After Hee-jin stops him from committing suicide, the two enter into a wordless but intense sexual relationship marked by sudden bursts of violence and self-mutilation. One particularly gruesome scene involving fish hooks caused an Italian journalist to faint during the official screening at the Venice Film Festival. The film creates a vivid sense of space, and is also a primary example of Kim’s curiously unconcerned approach to traditional character development. Many of the characters in his films seem to act not according to their own internal dynamics, but to satisfy the broader aims of the film. When, on the set, actress Suh Jung accused him of affording less importance to her character than to the dog that appears in the film, Kim replied that no, he considered her character to be on an equal footing with the dog – but to be less important than the boat she rows (see Lee 2001). Bad Guy (Nappeun namja, 2002) is about a pimp who abducts a university student and forces her into prostitution. Although registering the full scale of the horror visited upon the woman, the film also increasingly sides with its male hero, who has fallen in love with her. By the film’s end they are travelling the country and practising prostitution from the back of a truck: an ostensibly happy ending. While not apologising for the unethical behaviour or misogyny portrayed in Kim’s films, Steve Choe argues that their circulation through the international film festival circuit served to produce a crisis around the very issue of ethics. Such filmmaking, he notes, ‘seems to unsettle liberal tastes with images that violently force viewers to reconsider their familiar modes of cinema going’ (2007: 69).

Kim shifted into a more reflective, less controversial mode in 2003 to 2004, when he began basing his films on such themes as redemption and forgiveness. Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter … and Spring (Bom yeoreum gaeul gyeoul geurigo bom, 2003) is set on a remote lake and depicts progressive stages in the life of a Buddhist monk. Although not, as it sometimes appears to be, a film grounded in actual Buddhist doctrine, it showcased Kim’s visual creativity and his ability to tell stories with a bare minimum of dialogue. At its premiere at the Locarno International Film Festival the film was afforded breathless praise by many critics and enjoyed subsequent commercial success in Germany, Spain, the US and other territories.

The following year would see Kim win two high-profile festival awards: a best director award from the Berlin International Film Festival in February for Samaritan Girl (Samaria, 2004) and another best director award from the Venice Film Festival in September for 3-Iron (Bin jip, 2004). Both films were shot in the space of roughly two weeks on minimal budgets, funded almost entirely by pre-sales to foreign countries. 3-Iron in particular gained a reputation as one of Kim’s strongest works. Tae-suk (Jae Hee) is a man who lives his life breaking into empty houses, living there for a time (sometimes fixing broken appliances) and then departing, leaving everything in its place. In one home he comes across a woman named Sun-hwa (Lee Seung-yun) who suffers from marital abuse, and the two set off together to live their curious, alternative lifestyle. The simple and almost wordless story is in part a philosophy of living, with its critique of the idea of possession (both of physical objects and the husband’s possessive desire for his wife). In the film’s abstract final act, viewers begin to question whether the characters even exist, or if they are disembodied spirits, but Kim’s imagery is suggestive enough to support multiple interpretations.

Kim’s festival accolades and overseas success have turned him into a household name in Korea; nonetheless, his works have largely failed to find commercial success at home. His relationship with the local press and audience reached a low point in 2006 before the release of his thirteenth film Time (Sigan). Bemoaning Korean viewers’ lack of interest in art-house cinema, Kim vowed not to release any more of his films domestically if Time failed to sell 300,000 tickets. Although ultimately retracting his threat (the film sold just over 28,000 tickets), the incident highlighted the at-times wide gap between the domestic reception of Korean films and their commercial and critical reputation abroad.