BLOOD FEUD: THE LEWIS-LYONS

“GO-AS-YOU-PLEASE MATCH”

(1882)

Sophie Lyons may just be the wickedest woman in Detroit history. A career criminal by the time she reached eighteen, Lyons relocated from the mean streets of New York to Detroit and became such a nuisance that police took drastic measures to remove her from the scene.

Lyons’s nemesis was Theresa Lewis, one of the first female undercover detectives in Detroit history. But Lewis’s sketchy reputation came back to haunt her when, during the course of her investigation, she found herself on the wrong side of the cell bars.

The infamous Lewis-Lyons feud evolved into an epic confrontation between a zealous undercover agent and a woman dubbed “The Queen of the Underworld.” On three separate occasions, they went toe-to-toe in court, and on two separate occasions, they went toe-to-toe, literally, in street brawls that left both battered and bloody.

Drops of frozen rain struck the courtroom windows with the sound of a hundred fingernails tapping against glass. Coal and firewood became valuable commodities as a cold front descended on Detroit in January 1882. Inside the frosted widows, however, the heat would soon become intense. Sophie Lyons would take the witness stand, where she would do her best to smear her arch-rival, Theresa Lewis. It was the type of odd situation that made terrific headlines: the suspect testifying against the investigator for theft.

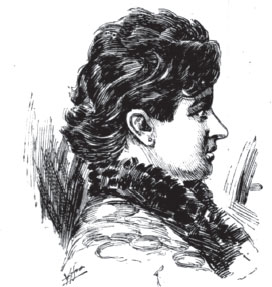

The rustling of papers and hushed chatter ceased, creating an eerie silence as Sophie Lyons walked into the courtroom. Reporters, sent by their newspapers to cover the showdown between Lyons and Lewis, began scribbling descriptions of Lyon’s black dress and matching veil, which concealed her eyes. One correspondent began to sketch the infamous queen of underworld Detroit.

As she sauntered down the aisle, Lyons smirked, her mouth curled up at one end in an expression of self-assuredness. She glanced at her nemesis and smiled.

Theresa Lewis leered at Lyons. As she frowned, a deep furrow appeared between her eyebrows, and lines radiated outward from the corners of her eyes. Her entire face tensed and took on the appearance of a clenched fist. Lewis could not survive on the same stage with a gifted actress like Lyons, and she knew it.

As a little girl, Sophie Lyons dreamed of a career in vaudeville, but she never made it under the limelight. Instead, the courtroom would become her stage. To an audience of twelve men in the jury box and a gallery filled with curious onlookers and reporters, Lyons put on a performance that generated more ink in the papers than shows of the most famous vaudevillians. A talented and accomplished role player, Lyons could take off one guise and slip into another like some women changed shoes. She could play innocent, spiteful, wronged or witty.

She could play a socialite or a girl from the gutter, all with a charm and charisma that could persuade twelve men.

Sophie Lyons was already a legend in the criminal underworld by the time she moved to Detroit in 1877. She had an early start, beginning her life of crime as an impish purse snatcher exploited by a seedy stepmother in a grim fairy tale without the happy ending.

A native of New York City’s Lower East Side, Sophie entered a life of crime at age six when her stepmother, Anne Levy, allegedly forced her to take to the streets as a purse snatcher and shoplifter. The wicked stepmother imposed a quota of three purses a day. Caught shoplifting in 1869, twelve-year-old Sophie began the first of an estimated forty stints behind bars.

Doe-eyed Sophie Lyons flirts with the police photographer’s camera in this mug shot. A former New York City detective included this photograph in his epic 1886 study of malfeasance titled Professional Criminals of America. Byrnes described Lyons as “Pickpocket and Blackmailer.” Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

At sixteen, she married Ned Lyons—a bank robber of national repute—and went to work as an operative in his gang. Together, they pulled off a Manhattan bank heist, a crime that netted them an estimated $3 million and made national headlines. Police faced enormous pressure to make a bust. They turned the city upside down looking for Ned and his attractive young wife. They kicked in the doors of known hideouts, strong-armed informers and bullied known acquaintances.

Eventually, they collared both. Sophie got five years in Sing Sing’s women’s wing. Ned got four but shortened his sentence to a few months when he sawed through the bars of his cell.

Ned would come back for Sophie.

On December 19, 1871, he engineered a daring escape for his wife during a blizzard. In the guise of a fruit seller, Ned parked a carriage in front of the women’s prison. Sophie, a trustee, pushed her way past the guard on duty and made a break for the carriage. Before anyone knew what had happened, the couple had raced away through the snowstorm. They made a beeline for the border and spent the next few months running a confidence game in Montreal.

The power couple of crime returned to New York, where they began to fleece vacationers on Long Island. Recognized by a detective, Ned and Sophie went back to Sing Sing in handcuffs to finish their sentences.

Woodward Avenue streetcars are frozen in time on this stereograph image, circa 1880, taken during the era of Sophie Lyon’s Detroit. Robert N. Dennis Collection of Stereoscopic Views, New York Public Library.

A New York Herald artist rendered this sketch of Sophie Lyons, “Queen of Criminals.”

Sophie decided that she had had enough of Ned; she vowed not to return to him.

Likewise, the State of New York made a vow to get rid of Sophie and released her on one condition: she must leave New York.

Ned-less, the Queen of the Underworld arrived in Detroit in 1877.

By the end of her first year in the city, Sophie had run afoul of the law when constables nabbed her pilfering lace from a Woodward Avenue haberdashery. The crafty con artist concocted a way to avoid a jail sentence. While awaiting trial, she knotted together the bedsheets on her cell cot and hanged herself just before the guard made his rounds. Sophie had timed the incident perfectly; the guard revived her, and the judge took mercy on her with a suspended sentence.

From Detroit, Sophie traveled to St. Louis, where she used the promise of sex to lure an older, married man to a hotel room and tried to blackmail him into writing her a sizable check to go away quietly. He refused; she lost her temper and, in a maniacal frenzy, tossed his clothes out of their hotel room window. The scene created such a ruckus, police arrested both Sophie and her older paramour, who as predicted refused to press charges. From St. Louis, Lyons traveled to Boston where, under the alias “Kate Lorangie,” she sweet-talked an aged lawyer named Charles Allen to her room at the Revere Hotel and threatened to expose him if he didn’t write a her check. Allen pressed charges for extortion, but the slippery Lyons beat the rap with a hung jury.

Back in Detroit, Sophie set up shop as the queen-pin of a theft ring that radiated out of Detroit to surrounding cities as far as Cleveland. Dozens of worker bees pilfered from their employers, shoplifted and grafted in smallscale confidence games. Lyons funneled all of the stolen merchandise to her fence, Bob McKinney, who pawned the hot items in various places throughout Detroit.

One of Sophie’s most trusted confidantes and part of her Detroit entourage, thirty-eight-year-old widow Theresa Lewis occupied a room in her boardinghouse.

The widow had a secret: she was an undercover agent for the Detroit Metropolitan Police.

By the time Sophie returned to Detroit following her St. Louis and Boston gambits, authorities had cooked up a scheme to remove her from the scene for good. They hired a female operative and planted her in Sophie Lyons’s overgrown garden of thieves.

Enter “Detective” Theresa Lewis.

By 1881, longtime Detroiter Theresa Lewis had survived a series of agonizing misfortunes. In the previous two years, Lewis had lost her husband, Robert, who died in an insane asylum, and thirteen-year-old son, Frank, who died of a congenital heart defect. To make ends meet, she ran a boardinghouse on Jefferson Avenue.

Like Sophie Lyons, Lewis was an adept actress who could slip into and out of a role as quickly and as effortlessly as changing her clothes. It would be a skill that would serve her well in the coming months.

During the summer of 1881, she went to work for Police Superintendent Andrew Rogers, who hired her to keep tabs on the activity of Sophie Lyons. Lewis rented a room in Lyons’s boardinghouse on Twenty-Third Street, bringing with her several blank notebooks that she planned to use to jot down evidence. With a fictitious sob story of being deprived of her home by thieving family members, Lewis quickly earned her landlady’s confidence and witnessed, from the “Lion’s Den” as she called it, Sophie’s criminal enterprise in action. Each night, under the kerosene lamp in her room, she made copious notes of what she had seen and heard.

Of all the merchandise palmed by Lyons and her gang of sticky-fingered thieves, her undoing in Detroit came down to three gold watches.

On September 24, 1881, the remains of President James Garfield visited Cleveland during a sort of postmortem whistle-stop tour. Sizable crowds gathered as people came from all over the Midwest to pay their respects to the slain president. For pickpockets like Lyons and her gang, the festivities provided an irresistible opportunity; they could bump into whomever they wanted without raising suspicion and then fade into the crowd with a pocketful of jewelry.

Lyons and Lewis made the railroad trip from Detroit to Cleveland, where Lyons circulated among the crowds and picked the pockets of unsuspecting mourners. Among the day’s haul were two gold watches, which she boxed up and sent to her housekeeper, Sarah Brew.

The housekeeper locked the watches in a drawer of Lyons’s bureau.

Back in Detroit, Lewis sneaked into Lyons’s room and found the gold watches. She took the hot goods straight to police headquarters and presented them to Rogers, who wrote down a detailed description of each watch, including any notable physical characteristics, before ordering Lewis to return them to the bureau drawer and keep watch for any suspicious activity.

Back at the boardinghouse, Lewis witnessed Lyons giving the watches to Bob McKinney with orders to sell them, which he did to local pawnbroker Jacob Smit. Lewis sent word to Rogers, who dispatched Detective Jesse Williams to Smit’s pawnshop, where he found the pilfered merchandise.

This chain of evidence—recorded by Lewis in one of her journals—would become a problem for both Lyons and McKinney.

On October 5, 1881, Lewis’s acumen as a private eye became evident. That afternoon, she saw Lyons and McKinney walking with Sarah Brew. Her suspicions raised, she decided to tail the trio.

When they boarded a streetcar and headed down Michigan Avenue, Lewis hired a carriage and followed them for a while. Along the way, she darted into her sister’s house to borrow a blonde wig, hopped back into the carriage and ordered the driver to catch up with the streetcar. When the streetcar stopped, she climbed aboard. Now in disguise, she could blend into the crowd without Sophie recognizing her. She even shoved a handful of pebbles into her mouth to disguise her voice with a gravelly tone.

Lewis slipped behind Lyons in line at the Grand Trunk Railroad and eavesdropped on her conversation with the ticket agent. She overheard Lyons say she planned to visit Ann Arbor the next day, October 6. Lyons had something planned.

On October 6, 1881, a dense crowd crammed into Floral Hall in Ann Arbor during the county fair to watch the hot air balloon demonstration. With so many bodies huddled together in one place, the scene was perfect for a pickpocket. As all eyes followed the balloon’s ascension, a woman resembling Sophie Lyons bumped into elderly Harriet Cornwell and nicked her gold watch.

A few days later, Sarah Brew received a letter from the postman. Since Brew could not read, she handed the letter to Theresa Lewis, who read it aloud. “Sarah, go to the express office, get the watch and chain and put them in my box. Don’t let anyone see it. Sophie.” The note was written in Sophie Lyons’s distinct scrawl. After Lewis read the note, Brew plucked it from her hands and tossed it into the fire.

Lewis subsequently witnessed a heated discussion between Brew, Sophie Lyons and Bob McKinney. Both Lyons and McKinney were upset because Brew went to the express office, as directed, but erred in giving the clerk the address of Lyons’s boardinghouse. It would be a critical error.

Acting on Lewis’s tip, Andrew Rogers went to the express office, where he found the package. Inside was Cornwell’s stolen timepiece.

Sophie Lyons faced two separate charges stemming from the theft of two watches in Cleveland and a third in Ann Arbor. These legal troubles mystified Lyons, who did not understand how police had managed to crack her system. She had stolen the watches under perfect conditions and sent them to an illiterate housekeeper who subsequently passed them off to her fence, McKinney, who sold the merchandise under assumed names. The information had to have come from someone inside her sphere. Someone, she now realized, had betrayed her.

By December 1881, the street-smart Sophie had smelled a rat, and she made overtures to Lewis about moving out of her boardinghouse. Lewis gathered as much property as she could carry and took it to Rogers’s office, where she turned over the merchandise as likely stolen.

Once Sophie learned about the police department’s plant, her vindictive side emerged. She marched straight to police headquarters and reported to Patrolman James McDonnell that Theresa Lewis had stolen various items from her, including an opera glass, a gold thimble, assorted jewelry and some bolts of fine cloth. She presented an itemized list of missing things and demanded Lewis’s arrest. A search of Lewis’s trunks revealed several of the items on Lyons’s list, so McDonnell clamped a pair of “bracelets” on Lewis’s wrists and dragged her to Rogers’s office.

Rogers believed that Lyons’s complaint against Lewis was a “put-up job.” Regardless, the complaint led to a highly publicized examination that took place in mid-January 1882. Justice John Miner had the unenviable job of trying to sift fact from fiction.

The courtroom swelled with the curious who wanted to watch the first official match between the local widow-turned-detective and the infamous Queen of the Underworld. Theresa Lewis came to the courtroom with several books containing notes she took during her investigation, and Detroit Police superintendent Andrew Rogers came to court ready to defend his operative.

Witnesses contradicted one another. One witness claimed to have seen the gold thimble in Lewis’ possession years prior to her association with Sophie Lyons; another swore she saw the same thimble at Sophie Lyons’ boardinghouse.

Several witnesses testified that Theresa Lewis had a bad reputation “for truth and veracity.” An equal number testified that they never knew her to lie. In an ironic twist, Sophie Lyons took the stand to testify against the woman sent to gather information against her. She wore a veil that shielded the top portion of her face from the gallery. When asked about the veil, she explained that she was ashamed of her past and did not want the public to see her face. As the items from Theresa Lewis’s trunk were placed in front of her, she identified each one as her property.

“I have had the opera glass in my possession for thirteen or fourteen years, and the ring for about one year,” Sophie testified. “I missed them from my house on October 10, and found them in Mrs. Lewis’ baggage. The pin is also mine; my husband made me a present of it. The solitaire diamond stud is my property.”

Sophie gave an emotional history of the diamond stud. Her late husband, Ned, gave it to her and made her promise to never part with it. The story made an impact on several in the courtroom, although her act did not fool the Free Press correspondent, who later wrote, “Her tale was so affecting that one shyster was seen to wipe a drop of suspicious looking water from the corner of his eye, and three others went out to get a drink.”

On the stand in her own defense, Theresa Lewis also claimed the diamond stud with an equally moving story involving a dead husband, testifying that she plucked it from her late husband’s shirt as he lay in his coffin. The Free Press correspondent was equally suspicious of this tale. “Fortunately, she has had more than one husband,” he sardonically quipped, “and it was perhaps equally fortunate that one of them is dead. Her story of how she removed the glittering bauble from the shirt front that lay above the pulseless heart of her dead and gone hubby was simply thrilling.”

Of all the witnesses who testified, Julia Thompson was the most valuable to Lewis’s defense. Unlike the other witnesses—a group that consisted of an alleged fence, a convicted fence, a woman known as a career criminal and others of questionable character—Mrs. Thompson enjoyed a spotless reputation. She testified to having seen several of the allegedly hot items in Theresa Lewis’s possession years earlier. She went on to identify the more expensive items, including the diamond stud, by specific physical characteristics like scratches.

Two faces of Sophie Lyons. Sophisticated society lady (left) and dreamy-eyed scammer with bedroom eyes (right). When she first came to Detroit, Sophie was known as a heavy user of morphine, a habit that earned her the epithet “the notorious Detroit morphine eater.” On a few occasions, she used her sex appeal to entice respectable men to her hotel room and then blackmailed them with exposure if they didn’t pay up. Left: Sophie Lyons, James Alba Bostwick, after unidentified artist. Albumen silver print; Right: Sophie Lyons, unidentified artist circa 1887. Albumen silver print. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Pinkerton’s Inc.

In his summation, Lewis’s attorney William B. Jackson attacked the character of Sophie Lyons in language so strong, she began to weep.

Jackson’s rhetoric paid off; Justice Miner tossed out the case against Lewis. Theresa Lewis had beaten the venerable Sophie Lyons in court.

Lyons’s legal troubles, however, had just begun.

Just after the case against Lewis concluded, Justice Miner summoned Bob McKinney to the front of the courtroom. While Sophie Lyons’s mouth dropped open, Miner informed the alleged fence that he now faced two counts of selling stolen merchandise—the two gold watches Sophie Lyons stole in Cleveland.

Sophie’s eyes widened when Miner called her name next. He informed her that she faced two counts of theft stemming from allegedly stealing the two gold watches.

Then, the two Cleveland watch owners—Elizabeth Sheldon and Fanny Zak—testified.

“I remember the 24th of September last,” Zak recalled. “There was a large crowd in the city. While going through the market, between 9 and 10 a.m., with a lady friend, I missed my watch, which I valued at $50. The watch was snapped off at the ring. It contained the initials ‘E.H.L.’ I missed the watch a half hour later. I went immediately to the jeweler who had repaired it for me and got its number.” Zak said she next saw her watch in the hands of a Detroit detective, who asked her to come to Detroit to testify against Sophie Lyons.

The testimony of Sheldon and Zak convinced Justice Miner, who set a date for the McKinney/Lyons examinations in Detroit Police Court. In the interim, Lyons would face her arch-enemy in an Ann Arbor courtroom, where she would try to convince a jury she didn’t steal Mrs. Crawford’s pocket watch. To do that, her attorney would need to discredit the widow-turned-detective. This set up a second epic confrontation in court. The Lyons-Lewis show was headed west.

Both Lyons and Lewis had claimed the diamond stud, and both had provided, under oath, a different postmortem provenance for it.

Dead men tell no tales, but living jewelers do. While both women wanted the valuable bauble, it actually belonged to neither of them—a fact that became clear in the most bizarre, and most telling, incident in the entire drama.

After Lewis’s examination, Sophie wanted the diamond stud back, but no one knew who it belonged to, which led to some head-scratching. Thanks to a little legal wrangling by her attorney, Sophie Lyons won the right to obtain the piece if she paid a bond of indemnity in the sum of twice its value.

So, Wayne County sheriff Clippert took the diamond stud to local jewelers Roehm & Wright for an appraisal.

Roehm scrutinized the piece. “Where did you get this?”

“Why do you ask?”

“Because it is ours. It was stolen from us over a year ago,” Roehm claimed.

“How do you know it is yours?” the stunned sheriff asked.

“Because it has a flaw in its side and has my private mark upon it.”

Roehm pulled a slim volume from the bookcase behind his desk. “In this I enter every stud I purchase,” he explained, “designating it by a private number which is scratched upon the setting. Opposite the corresponding number in the book I write a description of the jewel. This one is 149. Now take this glass, and you will find the number 149 upon the gold beneath the stone, and, upon its side, a flaw that is perceptible to the naked eye.” He handed a magnifying glass to Clippert.

Clippert’s jaw dropped open as he spied the telltale marks.

The diamond stud offered the best testimony about the veracity of statements made by Sophie Lyons in court. And by Theresa Lewis. Both evidently lied about owning it—even conjuring up sympathetic fictions that they knew would score points with the all-male court—and one of them likely stole it. In the end, neither would possess it.

The stud, valued at $185, wound up back in the showcase at Roehm & Wright, and Theresa Lewis’s reputation took another hit. The district attorney considered pressing charges but decided against it; he needed Lewis to testify against Sophie Lyons.

Lewis escaped the controversy, but the man who hired her did not.

The feud may have provided the last nail in the coffin containing Andrew Rogers’s career. Dogged by political adversaries and the press alike (the Detroit Post repeatedly labeled him a drunk), he resigned as superintendent of Detroit Police. Although he would later deny that his resignation stemmed from his association with Theresa Lewis, he couldn’t deny that the timing suggested otherwise; he left office at approximately the same time as Lewis’s examination on larceny charges.

On the evening of Tuesday, February 7, 1882, the two key figures in the upcoming trial—the defendant and the key witness against her—just happened to board the same train headed to Ann Arbor.

Almost immediately, Sophie noticed Theresa Lewis standing on the platform. She quickly approached the unsuspecting woman, pointed to her gloves and claimed Lewis stole them from her, too. Sophie clawed at her eyes, but Lewis managed to turn her head just in time and wound up with red scratches down her cheek. The two women grabbed each others’ hair and began tugging. The shrieks were loud enough to echo throughout the busy terminal. A crowd of curious onlookers formed a circle as the two combatants kicked and pawed at each other.

Following the din, a night watchman pushed his way through the circle and pulled them apart. They wobbled aboard separate cars of the train, each with a face crisscrossed by bright-red lines.

It would be much ado about a gold watch as the courtroom in Ann Arbor filled to capacity in February 1882. Everyone wanted to catch a glimpse of the infamous Sophie Lyons, unveiled. Curious housewives rubbed elbows with Detroit reporters, who anticipated the feud would come to a head when Theresa Lewis took the stand.

Lyons’s defense followed a line that Detroit Police didn’t hire Theresa Lewis to find evidence to convict Sophie Lyons—they hired her to manufacture it. The lawyers put forth a theory that Lewis’s story about tailing Lyons around town was fabricated and that a woman who resembled Sophie Lyons—not the Queen of the Underworld herself—stole Mrs. Cornwell’s watch. To prove their case, they put witnesses on the stand who swore they saw Sophie Lyons in Detroit on October 6. The prosecution called a handful of eyewitnesses who likewise swore they saw Sophie Lyons on the train to Ann Arbor and, later, at the fair on October 6.

As expected, the case hinged on star witness Theresa Lewis. For over four hours, both the prosecuting and defense attorneys grilled her about every minute detail of her story, but she did not waver. Following her epic turn on the stand, a parade of prosecution witnesses testified about her reputation for honesty; an equal number testified for the defense about her reputation for telling yarns.

At the end of the five-day trial, the twelve gentlemen in the jury box sifted through the conflicting testimony and decided to believe Theresa Lewis. They found Lyons guilty of larceny, and the court sentenced her to four years in the Detroit House of Correction.

Theresa Lewis had finally won the feud, or so it seemed.

Upon review, the state supreme court reversed the conviction. Lyons and Lewis were headed back to court. The second Ann Arbor watch trial would take place the following January.

Between the first and second Ann Arbor watch trials, Lewis took the stand against Lyons’s fence, Bob McKinney, in April 1882. McKinney faced larceny charges for his role in pawning the Cleveland watches to J.M. Smit under the alias “Harry Woodburn.”

Lewis explained that whenever Lyons was on one of her theft tours, McKinney would always show up at her boardinghouse the day before she returned. Like clockwork, he dropped by the Twenty-Third Street boardinghouse on Thursday, September 29, 1881, and asked Sarah Brew if any packages had come for him from Lyons in Cleveland. Lewis watched as Brew handed McKinney a small parcel containing the gold watches.

While on the stand, Lewis identified the watches recovered from Smit. The serial numbers proved they belonged to Fanny Zak and Elizabeth Sheldon of Cleveland.

Lewis’s testimony doomed McKinney, whose career as a fence ended later that afternoon when Justice Miner sentenced him to four years at the state prison in Jackson.

The second Ann Arbor trial took place in January 1883 and was a virtual duplicate of the first. Theresa Lewis took the stand and told the same story. The same witnesses swore they saw Lyons in Ann Arbor, and the same witnesses swore they didn’t.

The defense did manage to produce a surprise witness who raised more than a few eyebrows: Police Superintendent Andrew Rogers, who resigned his post in February 1882 amid rumors that he was asked to leave because Theresa Lewis faced charges stemming from her feud with Sophie Lyons. The chief denied it, but everyone knew that he had hired an agent with a sketchy reputation.

On the stand, Rogers characterized Lewis’s reputation for honesty as bad. “I can name a hundred instances that bear me up,” he said. Evidently, he felt very strongly about Theresa Lewis. Several times during his testimony, he lost his temper, triggering stern warnings from the court.

Rogers’s repeated emotional outbursts hurt his credibility with the jury, who once again chose to believe Theresa Lewis. Her story didn’t change; she didn’t waver in her testimony, and she was a sympathetic witness. And this time, Lyons’s lawyer Colonel John Atkinson’s attempts to discredit her seemed more like character assassination than viable efforts to get at the truth. Besides, the jurors reasoned, even if Lewis had a bad reputation, Lyons’s was worse.

Once again, the jury found Sophie Lyons guilty. Convicted a second time for the same offense, she was sentenced to four years by the court.

She went, kicking and screaming, to the Detroit House of Correction to serve her time.

By May 1883, Sophie Lyons had spent three months in the Detroit House of Correction. Still a person of interest to the press and public alike, Sophie agreed to sit for a brief interview with a reporter.

Hard time had taken its toll on the Queen of the Underworld. She had just emerged from a serious illness that gave her a gaunt, skeletal appearance.

The reporter described her as

no longer the attractive and rather pretty looking woman she was when walking about the streets of Detroit some months ago. Her complexion is very sallow, her once shapely and well cared for hands have lost their symmetry and look rough and coarse. A coquettish sparkle of the eyes and a girlish arching of the neck and shrug of the shoulder when greatly pleased at some remark, only remain to remind one of the woman who has had a strange and erratic career…

Lyons assumed the role of an innocent woman wrongly convicted, framed by the Detroit Police. There was little doubt whom she blamed for her unjust incarceration. Even the reporter was surprised by her reaction when he mentioned the name “Theresa Lewis.”

“This was sufficient to excite her to anger to the highest pitch,” he wrote. “Every sentence she uttered against her was wormwood and gall. Every muscle of her face and body suddenly grew rigid, her hands became firmly clenched and her frame fairly trembled with suppressed passion and hate.”

She sneered when the reporter noted that Theresa Lewis wanted to write a biography of “The Life and Times of Sophie Lyons” and used the opportunity to smear her antagonist. She remarked that Lewis’s autobiography would make more exciting reading than her own but swore to beat Lewis to the punch and write her own life story.

Lyons turned away, apparently embarrassed, as other convicts passed by and said, with a hint of sadness creeping into her tone, that she missed her veil.

The reporter finished his article with a description of Lyons peering out of the prison’s barred window. “Looking back he [the reporter] caught sight of Sophie standing near the window looking out upon the fresh, green grass in the prison yard, and fancied she was longing for that liberty which will probably not be hers for some time to come.”

He was wrong. For Sophie Lyons, history would repeat itself—again.

The Michigan Supreme Court reviewed Lyons’s reconviction and once again reversed it, leading to yet another trial, scheduled for October 1883, and yet another confrontation with Theresa Lewis. Sophie Lyons was thrilled. She would get another chance to publicly discredit her bitterest enemy.

By October 1883, however, the state’s linchpin had become seriously ill when she began a lengthy fight with breast cancer. As the trial date approached, it became clear that Lewis would be in no condition to take the witness stand, so the court postponed the third Ann Arbor watch trial and rescheduled it for the next session, to take place in March 1884.

The third Ann Arbor watch trial, originally planned for October 1883 but delayed due to the illness of Theresa Lewis, finally got underway in mid-March, 1884. At great expense to the state, jurors heard what had now become the same, sad saga from the same witnesses. The trial’s novelty came when Lyons’s attorney described an elaborate theory, he said, to put Sophie Lyons inside a frame.

Colonel Atkinson, in his two-hour closing statement, described a conspiracy theory in which millionaires from Jackson, aided and abetted by the police commissioners of Detroit, wanted to convict Lyons at any cost and framed her with evidence fabricated by their plant, Theresa Lewis.

The entire case, he argued, depended on Lewis’s story, which was full of holes. There was simply no way that she could have disguised her identity enough to fool Sophie Lyons. The note Lyons allegedly sent to Sarah Brew, with instructions to destroy it, made little sense; the housekeeper could not read. And none of the eyewitnesses could conclusively place Sophie Lyons in Ann Arbor on the day Mrs. Cornwell’s watch was stolen.

In his closing statement, Washtenaw County prosecuting attorney Whitman pointed out that the conspiracy envisioned by Colonel Atkinson would be preposterous. Such a theory would involve a Sophie Lyons lookalike, since several eyewitnesses saw someone remarkably similar in appearance prowling the campgrounds on October 6. The lookalike then sent the purloined watch to Detroit, where the package was picked up by Lyons’s housekeeper, Sarah Brew.

Despite Atkinson’s farfetched conspiracy theory, the jury did not believe Theresa Lewis. This time, they voted to acquit Sophie Lyons. The ordeal over a $300 watch, which cost thousands of dollars in court fees, had finally ended.

Lyons had won the day, but she still wanted her pound of flesh, which she would attempt to get on a Detroit street corner.

Just a week after the third Ann Arbor trial ended, the feud between Lyons and Lewis climaxed on the corner of Woodward Avenue and State Street. Lyons spied her mortal enemy walking past the Finney House and pounced on her.

She grabbed a fistful of Lewis’s hair and yanked with all of her might, popping the pins and sending her hat fluttering down the street. Before Lewis could react, Lyons kicked her in the stomach, a blow that dropped her to the ground.

The melee caused a crowd to form, and when it became clear that the two pugilists were the infamous press darlings, the onlookers decided to let them settle their feud without intervention.

Lewis, stunned from the blow to her midsection, swung her arms wildly in the air; in a frenzy, Lyons continued to kick her, the points of her boots digging into the fallen woman’s sides and chest, until passersby decided to step in and end the fray.

Driblets of blood ran from both sides of Lewis’s mouth as two men helped her to her feet. Her eyes glazed over and her head slumped down, so they carried her into the drugstore next to the Finney House while Lyons skipped away untouched.

The attack compounded Lyons’s legal problems with an assault charge; from her bed at No. 62 Madison Avenue, Theresa Lewis vowed legal revenge. “She took her boot heel and kicked me,” Lewis groaned to a reporter from her bedside. She would have one last opportunity when Lyons went to court for the Cleveland thefts—the examination continuously delayed pending the outcome of the on-again, off-again, Ann Arbor fiasco.

Battered and bruised, Lewis managed to square off with her old adversary for one final time during Lyons’s examination on larceny charges stemming from watches Lyons allegedly stole during the Cleveland funeral of President Garfield.

Despite failing health, she gave a lively and spirited turn on the witness stand. She proudly lauded her achievements as a detective and claimed that Rogers hired her to obtain evidence against not just Lyons but other thieves working in Detroit as well—evidence that she kept in a dozen written ledgers.

As Lyons’s lawyer Colonel John Atkinson cross-examined Lewis, she accused him of accepting stolen property—notably gold watches—as payment for services rendered. Her tone chafed Atkinson, who snorted that he wasn’t the one on trial. Weary of trying to break Lewis’s resolve and expose a crack in her story, Atkinson dismissed the wily witness.

Theresa Lewis stepped down from the stand for the last time. Once again, she had prevailed. The court found sufficient evidence against Lyons and ordered a trial, but the state’s linchpin had become deathly ill.

By the end of the year, Theresa Lewis was losing her battle with breast cancer. A doctor at the College Hospital operated in December 1884 and removed a large tumor. Her health briefly improved before she relapsed a month later.

With his star witness bedridden, prosecuting attorney Robison had little choice but to hold off on the funeral watch trial. His chance to prosecute Lyons for the Cleveland thefts would never come.

On May 11, 1886, Theresa Lewis finally succumbed to breast cancer. As she lay dying at St. Mary’s Hospital, Lewis expressed her belief that the second physical altercation with her bitter enemy, when Lyons jumped her and ruthlessly kicked her in the chest, aggravated her cancer—a common belief of the time echoed by contemporary newspapers.

Sophie Lyons never did any real time for the assault on Theresa Lewis. She would later claim that Lewis started the fight, and with the only witness six feet under, the case disintegrated. Lewis’s death also deprived the state of its only real witness against Lyons for theft in Cleveland, so once again she beat the rap. But Sophie’s time in Detroit had come to an end. With her fence in prison and her likeness known by every beat cop in the city, she had little choice but to move on.

In early 1886, the infamous Sophie Lyons left Detroit and returned to her native New York. Within six months, she notched another conviction for shoplifting and with it another prison stint of six months.

Sophie Lyons hated Theresa Lewis so much that the mere mention of her name caused her to fly into a rage. This emotion may have remained with her for the rest of her life. In her 1913 memoir, aptly titled Why Crime Does Not Pay, she does not once mention the name “Theresa Lewis.”