Country of origin: United Kingdom (in Belgium)

Date of construction: c. 1917

Location: Archaeological site, near Ieper, Belgium

THE MILITARY MANUALS supplied to the warring nations at the outbreak of war were full of advice in the construction of trenches. Differing only in detail, these texts expected and predicted that the digging of trenches would be a temporary defensive measure only. In fact, trenches had long formed an important part of the history and science of warfare. In siege operations in particular, trenches were significant. Dug as close to the footings of castle walls as possible, they provided protection for the men who were digging shallow tunnels or saps that were to undermine and breach the defences. They would also serve to house the assaulting infantry intent on that moment when they could surge into the fray. This principle, developed in medieval times, would be re-enacted in unrest in the longest and largest siege operations in history, fought on the Western Front from 1914 to 1918.

The development of this type of trench warfare was an inevitable consequence of the improvement in weaponry, and in particular rifled weaponry, which could fire – with great accuracy, range and velocity – projectiles from as small as the rifle bullet to as large as the artillery shell. Unprotected, the infantryman was vulnerable to devastating firepower at longer ranges, and with the advent of quick-firing weapons such as the latest field guns and machine guns, the only way to ‘bite and hold’ a position was to ensure that men got to ground as soon as possible, digging into the earth to gain the maximum protection that could be afforded. Rifled weapons had contributed to the development of trench warfare in the American Civil War of 1861–65, which had gone from Napoleonic ranks to trench operations over its five years; and its appearance in modern warfare was heralded in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05.

Excavations in Flanders in 2005 expose A-frames and corrugated iron revetments.

In the First World War, entrenchment of the Western Front was an inevitable consequence of the fight for position that took place during the ‘Race for the Sea’ in the autumn and winter of 1914. From this point onwards the engineers of all the protagonists worked to develop and improve trench fortifications within unfavourable ground conditions, and to protect the infantry from both the attentions of the enemy and from the elements. The best positions were quickly taken and the lines set in position that would become the zone of trench warfare for some four long years.

Engineer trench design needed consideration of ground conditions. The trench illustrated was one that was excavated in the Ypres Salient in 2005 and demonstrates in some detail how these specialist soldiers coped with the difficult ground – and show how unexpected challenges of extended siege warfare became a high science in itself. Recent archaeological studies in northern France and in Flanders have allowed scientists and historians to add further dimensions to our understanding of trench warfare provided by accounts, official histories and photographs. Here, engineers have tried to combat the inevitability of water collecting in the bottom of the trench, thereby promoting ‘trench feet’ – a condition akin to frostbite – as men struggled through the water-logged trench. Prefabricated wooden A-frames were sunk into the ground. The crossbar of the ‘A’ provides a support for an elevated walkway or duckboard. Water could accumulate below and could be drained away, if skilfully done. The rising timbers of the frame provided rigid support for the trench sides, known as slopes, which were important if the sides were not to collapse in on the trench garrison. This revetment differed from trench to trench, from army to army. In the case illustrated from the Ypres Salient, corrugated steel was used; however, sandbags, wattle hurdles, timber – all were tried according to whatever was available. Trench construction varied between nations – in many cases wattle was used as a natural revetment type.

In many cases, the depth of trenches was limited by the local geological conditions, with water-bearing layers often close to the surface. In such situations, sandbags were used to build up the trench to an acceptable height of parapet. Building up the parapet meant using the A-frame in such a way as to support construction of ‘high command’ trenches, or simple sandbag breastworks.

In all cases, the trench lines showed increasing sophistication as the war moved from temporary trenches to those intended to house a garrison committed to a lengthy stay. With the British and French adherence to the doctrine of the offensive – with trenches little more than a ‘phase’ – the development of the A-frame represents a recognition that trench warfare was here to stay.

German barbed wire.

Country of origin: Germany

Date of manufacture: c. 1915–16

Location: Private collection

BARBED WIRE HAS become as much a metaphor for the suffering of the First World War as trenches and gas. As one contemporary writer, Reginald Farrer, put it in 1918: ‘remember the work that every length of this wicked weed has done – the dead and dying caught in its merciless mesh, and kept hanging on its thorns for hours and days.’ For the soldiers themselves, the grim humour practised in the trenches would include reference to missing soldiers ‘hanging on the old barbed wire’, incorporated in a popular ironic song: ‘If you want to find the old battalion, I know where they are, They’re hanging on the old barbed wire.’

This twisted, rusty sample of barbed wire was recovered from the fields of France, where fragments of the battles that scarred them still abound. It is German; we know this because of its peculiar form – a single wire twist with a square cross section, and a particularly fearsome set of barbs. Such wire is encountered wherever the Germans set their hand to building field defences or fortifications, or in the construction of prisoner-of-war camps. It is seen in the fields of France and Flanders, on the shores of Gallipoli, and still marking the boundary of long-gone POW camps. This specimen came from Gommecourt, a salient or bulge in the German front line on the Somme, jutting forward pugnaciously towards the British. Gommecourt was the scene of an ill-fated diversionary attack by the British 56th and 46th Divisions on 1 July 1916, an attack that left more than 2,000 men dead, five times that suffered by the German defenders. The barbed wire had played its part.

Austrian barbed wire entanglement.

Though we often associate barbed wire with the Great War, its origins lie in the American West, and it is amongst the most significant inventions of the late nineteenth century. Anyone who has visited the endless rolling plains of Wyoming or Montana in the United States cannot fail to be impressed by the grandeur of the landscape, and to imagine the vast herds of bison so essential to the Native American way of life. This lifestyle was to meet its end with the relentless move of American families westwards, an opportunity for ‘homesteaders’ to take up the US government’s offer of 160 acres of free land on those very prairies. With the homesteaders came an alien concept to the native peoples: enclosure. Well known, though, is that the enclosure of this wild grassland was accomplished through a simple device – barbed wire. With huge plains to cordon off, and no hope of using natural stone walling or the split-rail fencing so common in the eastern states, a technological solution was required. And that solution was the wire that became known as ‘the Devil’s rope’.

Invented in 1873 – and patented a year later – by Midwest farmer J.F. Glidden, barbed wire in its earliest incarnation differed from all other types of wire for fencing. Of paramount importance were the small double-strand twists that had sharp, unforgiving barbs set in opposite directions. The intention behind these was obviously to create a barrier to movement, the barbs warning straying animals to keep to their side of the fence. But anchoring the small bunched barbs was difficult, and Glidden’s approach was to bind them in place with a second piece of wire twisted over the first, locking the barbs in place. From this point barbed wire attained its fearsome reputation, and with it came a host of competitors and alternatives. It is estimated that there are at least 2,000 different types of barbed wire, and a host of collectors to boot.

With the western prairie cordoned off by fence posts and barbed wire, the possibility arose of the use of the invention in the protection of field works and the production of military obstacles, such as trench warfare itself. Military obstacles such as this had a long history prior to the opening of the Great War. Pallisades were well used, as was the medieval obstacle provided by stakes in the ground or reversed trees – both known as ‘abates’. According to the standard British text Military Engineering (Part 1) Field Defences (1908), such obstacles were to be ‘used in conjunction with defensive works, but may also be employed in the open to impede an advance of troops, or to increase the difficulties of a night attack’. The use of barbed wire as one of those obstacles has tentative beginnings in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Though the possibilities of trip wires or entanglements of plain wire intended to ‘impede the enemy’ were understood at this point, it was arguably the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 that saw the first thoroughgoing use of barbed wire entanglements as we know them from the Great War. Perhaps learning from this experience, the British Army was to sagely comment, in its 1908 manual, that such obstacles ‘should not be liable to serious damage from the enemy’s artillery’, noting that ‘Against entanglements and abatis, artillery fire has very little effect’. Finally, it judged, ‘wire entanglement is the best of all obstacles, because it is easily and quickly made, difficult to destroy, and offers no obstruction to view’. So it was that barbed wire made its way onto the roster of military materials of the First World War.

British barbed wire pickets.

It is possible to follow the thickening of barbed wire entanglements through the history of the war. In the opening months, barbed wire was an encumbrance to the retreating troops, retreating in the face of the German thrust through Belgium. A few strands were to be encountered here and there; a few strands more specifically associated with the protection of horse lines and the creation of warnings. But with the fixation of the trench lines in what became known as the ‘Race to the Sea’, as both sides tried to avoid being trapped behind their defensive positions there came the need to create obstacles to ‘impede the progress of the enemy’.

Barbed wire formed a significant component of the field defences of the Great War; it was to need constant attention. Wiring parties on both sides would enter no-man’s-land under the cover of darkness, in patrols of two to three men to inspect the integrity of the defences or cut paths through their own wire in preparation for a raid or in larger fatigue parties to repair and improve the front-line wire. Wire was brought up the lines by fatigue parties who, usually under the instruction of a sapper officer or NCO, would carry out the work in darkness. Such parties would be in a constant state of readiness; any noise would trigger off a flurry of star shells and Very lights intended to illuminate the interlopers, picking them out in stark silhouette against the night sky, an easy target for a sweeping machine gun or targeted artillery barrage. It was the invention of the screw picket – which spread like wildfire on both sides of no-man’s-land – that meant complex wire barriers could be constructed relatively noiselessly, soldiers literally winding them into the ground. As the defences got stronger, the barriers seemed almost impervious; the actual limit of attack often stuttered and faded at the barbed barrier. A wartime tune recalls:

If you want to find the old battalion,

I know where they are, I know where they are,

I know where they are

If you want to find the old battalion,

I know where they are,

They’re hanging on the old barbed wire,

I’ve seen ’em, I’ve seen ’em,

hanging on the old barbed wire.

I’ve seen ’em, I’ve seen ’em,

hanging on the old barbed wire.

Country of origin: Australia (in Ottoman Turkey)

Date of manufacture: 1915

Location: Australian War Memorial, Canberra, Australia

THE DEVELOPMENT OF trench warfare led to the proliferation of individual trenches. There were, after all, many types – zig-zag or traversed trenches for fighting; longer trenches intended as thoroughfares to allow troops to get to the front and wounded soldiers to get away from it; trenches designed to house garrisons so that they were not in the front line; and, trenches in the rear areas to be held if the enemy broke through. From inconclusive scrapes in the ground in Flanders, trenches quickly became complex pieces of architecture that required planning and development. Trench systems soon became like subterranean towns housing thousands of people – all of them careful not to raise their heads above the parapet in daylight, for fear of having it shot off by snipers.

With the proliferation of trenches and trench systems came the need for mapping and signage so that new occupants could get their bearings. A routine developed on the Western Front whereby battalions of men would be cycled through the trenches, typically spending up to a week on the front line, before being taken out to the reserve trenches and then finally ‘out on rest’ – though often such rest spells meant a return to the front line as rations carriers. It was necessary to direct soldiers through the maze of trenches, for although they were theoretically constructed in parallel lines – at least in the early stages of trench warfare on the Western Front – the re-entrants, salients and redoubts would be interconnected by communication trenches (CTs) and minor trenches intended as latrines, entrances to dugouts, trench mortar batteries, and so on. Often, these were challenging. Relief of the trench garrisons relied upon local knowledge – with guides detailed to lead men in and out, reminding them all the while to keep their heads down in the face of artillery and rifle fire.

Shell petrol tins, as used in the trenches.

Most soldiers would travel to the front line from the rear areas along crowded CTs at night – bustling, narrow thoroughfares 6ft deep, with barely enough room for men to pass. Although relieving battalions would be guided to the front by experienced soldiers from the battalion about to be relieved, sign boards would still be necessary to direct them, perhaps picked out by candlelight. Many of the long CTs had picturesque names, chosen at will and whim; these would be painted on rough and crude boards to aid in direction finding. Such boards would also exist at the front line; others, with a more urgent message, might warn of the dangers from snipers, artillery fire or the physical hazards of loose or low wires, or treacherous duckboards.

Though trench warfare is most commonly associated with the Western Front, different species of it developed in the icy mountains of the Alps, cut into the solid rocks of the high mountains that separated Italians from Austro-Hungarians, as well as in the complex terrain of Salonika, where a multinational force faced the Bulgarians across malaria-infested valleys and challenging mountain terrains. But arguably the most intense and challenging conditions were those that faced the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) during their eight-month occupancy of the steep, parched and crumbling slopes above Anzac Cove in the Gallipoli Peninsula. From April 1915 to January 1916, British, Indian, French and ANZAC forces clung to small enclaves of the peninsula while they planned the opportunity to break out of their extended beachheads – an opportunity that had been squandered when they first landed. Here, with impossible routes and ever-so-close trenches, precarious saps and shallow-scraped dugouts, the ANZACs attempted to outwit their Ottoman opponents. And, through it all, finding their way to the front line was fraught with danger.

This trench sign, from the collections of the Australian War Memorial, is made from a rectangular Shell Petroleum tin adapted to make an illuminated trench marker, which was recovered from the battlefields of Gallipoli in 1919, a silent sentinel left behind after the evacuation. The marker was found on a hill above Shell Green in the ANZAC sector. Like much of the life of the ANZACs at Gallipoli, it is extemporised; in this case, fashioned from recycled materials. The reuse of materials such as tins and wooden boxes was commonplace at Gallipoli, especially during the early stages of the campaign, when there were major difficulties with supplies. On the front of the tin, over the impressed ‘Shell Motor Spirit’ details, is punched the text ‘Q5 / TO / FIRING / LINE’. Q5 was a trench or sap leading to the firing line. The text has been created by nail punch, which forms the outline of each letter and number. The side of the tin has been cut to form a rectangular ‘door’ to allow a candle to be inserted inside the tin to illuminate the text at night in order to assist soldiers making their way in the dark. There is evidence of the war that raged around this mute bystander: there is a small shrapnel hole in the front of the tin, and another in the side ‘door’.

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Date of manufacture: 1917

Location: Private collection

LOOKING OVER THE parapet in daylight was most unwise; snipers would have weapons fixed in position, targeted at dips in the parapet, at latrines and crossing points, and at loophole plates. There was continual loss of life on the Western Front through the actions of snipers in this way, combined with the altogether random attentions of the artillery shell. From early on, the need to be able to look over the parapet to observe activity in no-man’s-land led to the production of specially designed ‘trench periscopes’. Illustrated is the British No. 9 box periscope. Made by ‘Trenchscope Ltd’ in 1917, this is a typical issue item. This one saw service with the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in France, and is well preserved, found together with spare mirrors and its carrying bag. Cheaply made with boxwood, it is nevertheless complete.

In an issue of Transactions of the Optical Society for 1915, the basic parameters were laid down for trench periscopes, the object of which, it was stated, was ‘to give the soldier a view of his front whilst his head and person are sheltered’. Its author, W.A. Dixey, distilled these into four points: 1) portability; 2) degree of shelter provided; 3) field of view; and 4) camouflage to the enemy. Many patent versions were produced to try to achieve these aims; several of them were adopted officially, others were available for private purchase. Most provided a non-magnified field of view; magnification could be gained by the use of binoculars in association with the periscope.

A No. 9 Box Periscope in action.

For portability, a simple mirror attached to a stick or bayonet was the most effective. More commonly, day sentries would be stationed next to a No. 9 Box Periscope, which provided a clear field of view sufficient for most trench duties. Spare mirrors were essential – all too often they would be spotted by the enemy and ‘sniped’; shot out with a shower of glass splinters. Although portable, such periscopes were fixed at sentry posts throughout front-line trenches, effectively disguised from sniping by the use of sandbags and sacking.

Officers were drawn to more portable periscopes; the most commonly encountered periscope used by officers was the Beck’s No. 25, issued from 1917, which comprises a simple small diameter brass tube, with detachable handle and a focusing eyepiece. This effective piece of equipment was not only light, durable, difficult to spot at a distance and long enough to provide the observer with sufficient protection, it was also a magnifying periscope, and popular with officers. A great many other types, many not as effective, are also known. The proliferation of ‘trench’ periscopes during the war matched the increasing sophistication of the enemy in providing snipers. For the Germans, equipped with the highest quality lens-making factories, and observing from the high ground, the field of view was often clear; for the Allies, restricted to their simple mirrors, observing ‘over the top’ was much more of a challenge.

Country of origin: Germany

Date of construction: 1914–18

Location: Hill 62 Sanctuary Wood Museum, near Ieper, Belgium

MORTARS ARE WEAPONS that are intended to lob a heavy projectile in a steeply arcing trajectory over a short distance. Their use dates back at least five centuries, when they were used to assist in the breaking of sieges; unlike normal field artillery with their flat trajectories, mortars have to be deployed relatively close to their ultimate targets. Mortars are muzzle-loaded and relatively simple; they require just a sufficient explosive charge to blast their projectile towards the enemy. Mobile, and capable of being used by infantrymen, they were tailor-made for trench warfare. Trench mortars were to become increasingly sophisticated as the war proceeded; used as a means of destroying or reducing enemy trenches, they were capable of killing large numbers of men in any given trench.

The Minenwerfer was a German trench mortar that was effective at both destroying sections of the front-line trench and reducing the morale of its occupants. Minenwerfers came in three sizes: heavy (25cm shell), medium (17cm shell) and light (7.58cm shell). Feared in combat, but mobile like machine guns, they were typically captured during trench raids. The example illustrated is a typical 25mm schwerer Minenwerfer, one of three different types on display at the Hill 62 Trench Museum near Ypres. This museum has been open since the 1920s; it is not inconceivable that this relic has been there the whole time, examined by tourists and pilgrims alike. But today, this rusting metal, industrial-looking object is difficult to translate into the snarling intensity of the weapon in combat, as it is to give physical expression to the memories of the combatants, who universally feared the power of these weapons. As described by Private Alfred M. Burrage of the Artists’ Rifles: ‘There is no explosion which, for sheer gut-stabbing ferocity, is quite like that of a Minenwerfer. The bursting of one close at hand was like one’s conception of the end of the world.’ As the shell could be observed in flight, sentries with whistles were placed in the front line, their duty to observe the flight of the mortar shell and alert their comrades.

British ‘toffee apple’ mortar rounds.

The British experimented with a variety of contraptions – including catapults firing grenades – but the first effective mortars started to appear in 1915. These included the ‘toffee apple’ mortar: a 2in diameter tube firing an explosive charge mounted on a long shaft, but which was liable to destabilise the round in flight. More reliable was the Stokes mortar, a simple 3in diameter drainpipe affair that was effectively the prototype for mortars in use today in armies across the world. Stokes bombs were dropped into the tube, a striker activating the charge and propelling the round up to 1,500 yards. Stokes mortar bombs still litter the former battlefields in out-of-the-way places; unstable still, they remain volatile, a deadly echo of a past war.

Successful as the Stokes was, it was the Minenwerfer that was most feared. Our rusting example is one of at least 16,500 produced and used during the war, a testimony to their value in the extended trench warfare siege.

Country of origin: Germany

Date of manufacture: c. 1916–18

Location: Private collection

THE SCIENCE OF artillery increased in complexity throughout the war, as the gunners tried to outwit both the engineers – who had designed and built the fortifications that sheltered the infantry – and the artillerymen opposing them. But at the commencement of war, the primary role of artillery was as an anti-personnel weapon and, as a consequence, most field artillery pieces were equipped with shrapnel – explosive shells with steel bodies that were filled with around 200–300 lead or steel balls, a load that was intended to scythe down attacking armies as the shell exploded. Unlike high explosive shells, which were packed with a large amount of explosive, shrapnel was equipped with only a small charge that was sufficient to blow off the head of the shell and to liberate the bullets through the action of a disc that moved up the central tube, forcing them out. In British use, shrapnel shells were the only ones available when the Royal Field Artillery went to war with the British Expeditionary Force in 1914.

Shrapnel was an important weapon and was used to great effect as trench warfare developed in earnest. With infantry assaults committed to the deadly, shell-swept no-man’s-land, it was incumbent upon the artillerymen to provide a protective shield. New techniques led to the acceptance of creeping or box barrages, protective curtains of fire that would hopefully allow the infantry to get across unmolested, the curtains lifting according to a timetable in order to allow them to advance. The same scything action that was used against men was also employed against barbed wire obstacles, but required precision to do so effectively – an ideal that was not always easy to deliver, leaving soldiers facing the uncut wire while unprotected in that grim zone between the trench lines. All too often shells failed to explode, due to faulty fuses or defective drive bands, and this meant a staggering number of ‘duds’ left on the battlefield.

German large-calibre shell at La Boisselle, on the Somme battlefield.

For trench destruction, and for seeking out and destroying dugouts and other shelters, high explosive shells were more effective. The projectile delivered a huge explosive force, capable of creating huge craters and blowing in large sections of trench, while the explosively burst shell wall would create a high-velocity shower of shell splinters that were razor sharp. The most effective were those delivered by larger calibre and higher trajectory field howitzers. Such weapons would ensure that the rain of shells was as near vertical as possible. The shell fragments illustrated are from a high-velocity shell that burst above a British dugout close to the front line near to the destroyed village of Zonnebeke, in the Ypres Salient. No doubt fired from a German howitzer, its purpose was to seek out and destroy British trenches and dugout works, and, ultimately, to kill its occupants. The size and shape of each shard – over 12in long and 1in thick – is terrifying.

It has been estimated that 70 per cent of all casualties were wounded or killed by artillery fire on the Western Front. With increasing precision, artillerymen developed new ways of delivering their goods, with creeping and box barrages intended to provide a protective screen around those attacking, isolating those within from the attentions of the defenders outside the curtain of shell fire. Complex ranging techniques and increasingly complex artillery maps meant that the gunners belonged to an extremely professional and scientific corps by the end of the war. For the soldier, avoiding the attentions of the enemy’s artillery fire was paramount. In the ‘live and let live’ system that developed in some sectors of the Western Front, maintaining the status quo was the aim, thereby avoiding anything that would bring down a barrage in suspicion of unwanted extra activity or evidence of military preparation. Soldiers soon got used to the sound of incoming fire: the ‘whizz bang’ of the quick-firing field gun, or the ‘crump’ of the explosion of the heavy howitzer – explosions that created forceful blasts and plenty of black smoke. These would also be given the names ‘woolly bear’, ‘Jack Johnson’ (after the hard-hitting black heavyweight boxer) and ‘coal box’. Heavy shells would kill by the action of the high explosive that could tear apart fortifications and human flesh alike; wounds from the jagged, cruel shell fragments like those illustrated were particularly feared.

Country of origin: Germany

Date of printing: 1916

Location: Private collection

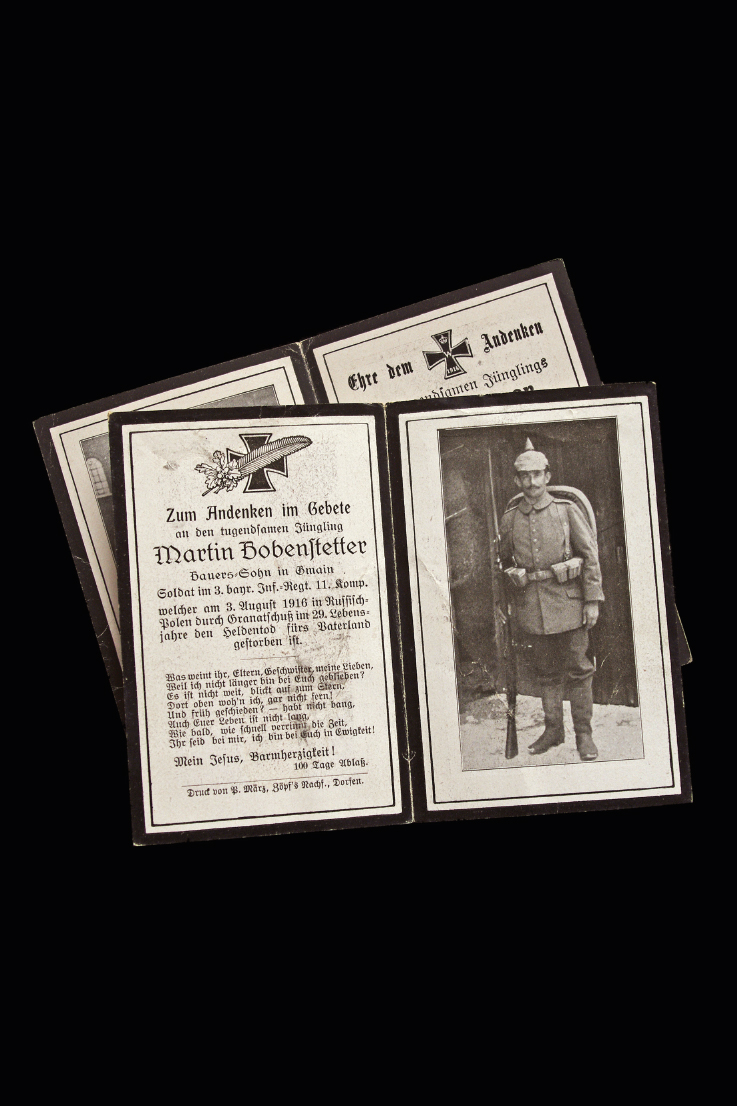

THE IMAGE OF the fresh-faced German infantryman is all too often portrayed in the issue of ‘death cards’, or Totenbild – and many young men, such as Martin Bobenstetter of Bavaria, would be killed by the random and unforgiving effects of artillery fire. Relentless Trommelfeuer (drum fire) bombardments were common from late 1914, and they only increased in intensity as the war dragged on.

Death cards are a feature of German funerary culture; from the 1840s it was a common occurrence for Catholic families to arrange for the printing of small card folders bearing religious observances, images of Christ or the Madonna and religious tracts. The issue of the cards traditionally marked the passing of family members, alerting the local population to the loss of a loved one and asking them to partake in a religious observance, the act of praying for the deceased over a mourning period of, typically, 100 days.

With the coming of war, the number of cards issued became truly staggering. Early examples often give details of the military career of the deceased, the regiment, the location and date of death – each one a witness to the slaughter of German soldiers fighting the war they had long feared: the war on two fronts. The card illustrated is typical. It tells the poignant story of a young man who was killed on the Eastern Front by a random act of shelling in 1916 – like so many before him, and so many afterwards. The folded card has the appropriate religious observances and opens on an image of a young man in uniform:

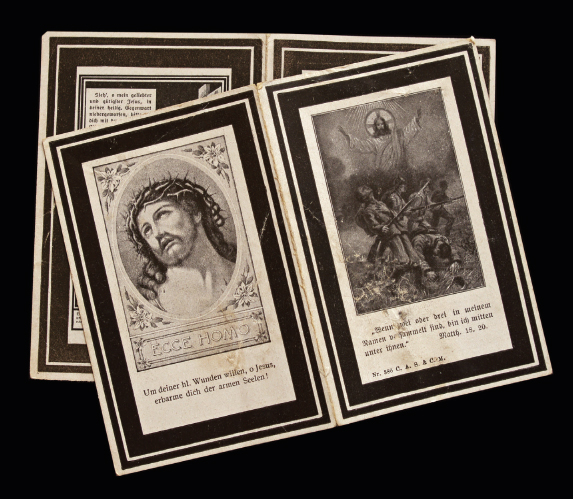

Religious observancies on the exterior of the cards.

To remember in prayer the virtuous youth Martin Bobenstetter

Farmer’s son in Gmain. Soldier of 3rd Bavarian Infantry Regiment, 11th company who was killed by shellfire on the 3rd of August 1916 in Russian-Poland, dying a hero’s death for the Fatherland.

Martin Bobenstetter’s regiment, the Königlich Bayerisches 3, Infanterie-Regiment ‘Prinz Karl von Bayern’, had already suffered before it was transferred to the Eastern Front. In the spring of 1916 the regiment was engaged at Verdun, taking and consolidating Hill 279, the ‘Termitenheugal’ at Avocourt. Suffering 70 per cent casualties, the regiment was withdrawn to the east, only to face the Russian Brusilov Offensive that was launched against the Austro-Hungarian-held front. General Aleksei Brusilov is credited with reviving the fortunes of the Imperial Russian Army by delivering a crushing blow on the Austro-Hungarians. Fought from 4 June 1916 through to September, new tactics were brought to bear with good effect: the use of lightning barrages and shock troops to gain infiltration. With the line contracting and reeling, the Austrians and their German allies had to reel back to absorb the pressure. In the firing line close to Volhynia was Martin Bobenstetter, brought from the hell of Verdun.

A Catholic, Martin was a farmhand by trade, and unmarried. Born on 13 October 1887 in Gmain, the son of Martin and Anna Bobenstetter, he joined the army on 14 August 1914 and took part in the defensive operations in Artois in 1915. By the time of his death, Martin had already been wounded at least once, in Artois in 1915. On 26 May 1915 he was hit by a piece of shrapnel on his upper thigh. Artillery accounted for the majority of wounds and deaths in the Great War; Martin was not alone in having been hit on several occasions by shell fragments. And his family were no strangers to tragedy. Already, two of his brothers had been killed: Matthäus Bobenstetter (on 28 October 1914, aged 28) and Michl Bobenstetter (on 23 May 1916, aged 21). With the loss of Martin, killed just four months after his second brother, the Bobenstetters would suffer once more; their eldest son, Georg Bobenstetter, was killed on 9 April 1917. All four brothers are commemorated in the church of Dorfen–Schwindkirchen, in Bavaria. By no means unusual, the death card records the loss of one of four brothers, and the decimation of a family by war.

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Date of manufacture: 1915

Location: Private collection

WITH ARMIES TRAINED to a high state of efficiency with their rifles in the early part of the First World War, with the advent of trench warfare, the most effective weapon was the grenade.

The British Army went to war with an extremely cumbersome example – the No. 1. The No. 1 was a 16in stick grenade with a cast iron explosive chamber and streamers to make it stable in flight. As a safety precaution, the No. 1 had a cap that was held in place by a safety pin. This cap was intended to protect the percussion fuse, which in normal circumstances was not fitted. Bombers had first to fit the fuse, the bomb being armed and ready for throwing. Streamers attached to the grenade were intended to ensure that it fell head-first – thereby exploding on impact. But, unlike its German equivalent, the Steilhandgranate, it had a fatal flaw – the combination of a long handle and a percussion striker. The bomber had to be extremely careful not to hit the side of the trench when preparing to throw it, a difficult proposition in the confined spaces of the trench. In view of this, the No. 1 grenade was updated on 21 May 1915 with a shorter cane or turned wood handle, thereby reducing the length of the grenade to a more manageable 12½in.

Difficulties of supply, and problems with the ungainly and dangerous nature of these percussion-fused stick grenades, meant that by 1915 soldiers were making their own grenades, ignited by a slow-burning fuse – usually at the rate of 1in of fuse per 1.25 seconds of delay. Typical of these emergency bombs is the ‘jam-tin’ bomb – literally a tin filled with explosive gun cotton and shrapnel balls – that is particularly associated with the Gallipoli Campaign of 1915. They were unreliable and were to decline in popularity with the introduction of the Mills bomb in May 1915, named after its principal inventor William Mills. Illustrated is a typical example, from 1916.

Officially designated the No. 5 grenade, the secret of the Mills bomb’s success lay with its ignition system, which used a striker that was activated when a pin was removed and a lever released; the lever was then ejected and a four-second fuse activated, during which time the bomber had to throw the grenade. The body of the grenade was formed of cast iron, and weighed 1lb 6½oz; its surface was divided into sections to promote fragmentation. Coloured bands indicated its fillings: red at the top to demonstrate it had been filled, pink for ammonal (like our example – now made inert), green for amatol. At the heart of the grenade was a centrepiece that contained separate cavities for the striker and the detonator. The striker was kept cocked against a spring, the striker lever holding the striker firmly in position when held against the body of the grenade, locked there by the action of the split safety pin until the bomber removed the pin and threw the grenade. On throwing the bomb, the lever flew off, thereby releasing the striker. The impact fires the cap, lighting the safety fuse, and this burns for five seconds before igniting the detonator, which then sets off the main charge.

The Mills bomb was reliable and tough; in its 1916 manual, Notes for Infantry Officers on Trench Warfare, the War Office was clear in its deployment as a trench weapon: ‘[Mills] Grenadiers will principally be employed in clearing trenches […] and also to check and destroy hostile bombing parties.’ The bomb received much use, and continued its task into a second world conflict.

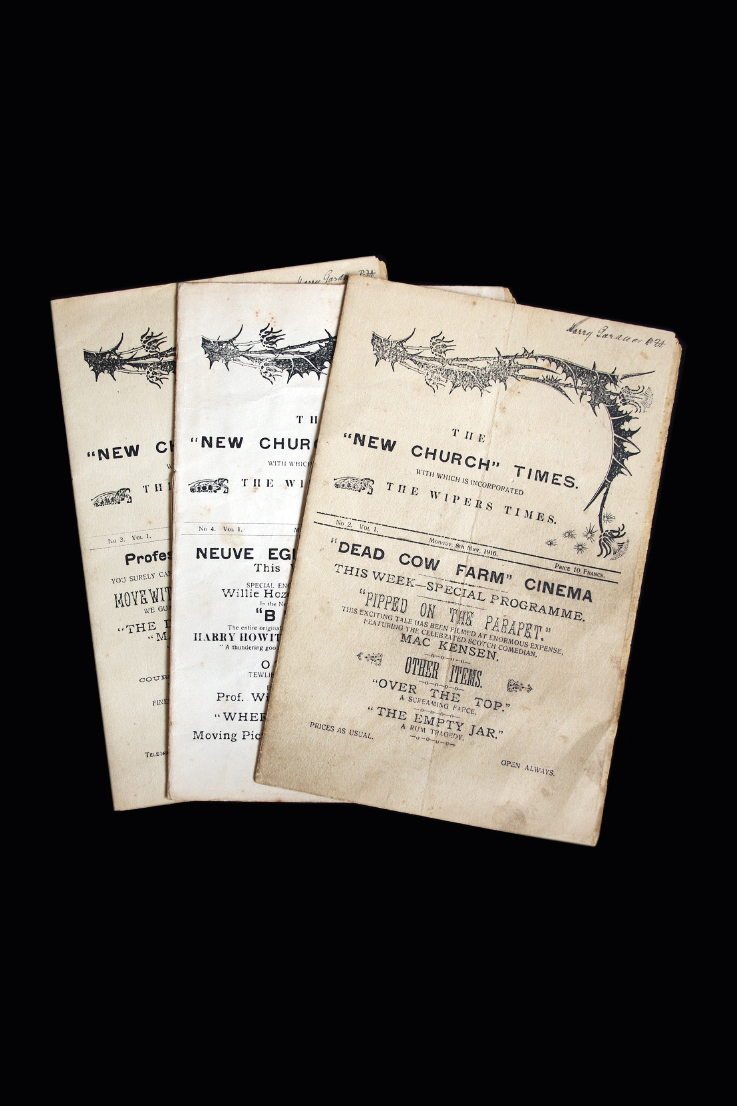

‘New Church’ Times, successor to The Wipers Times.

Country of origin: United Kingdom (in Belgium)

Date of printing: 1916

Location: Private collection

BY MID-1915, the war on the Western Front had settled down to the daily grind of trench warfare. Though in many sectors this meant standing on the defensive, in several hotspots there was more or less continuous action and activity, with the war prosecuted on land, underground and in the air, to varying degrees.

In some sectors, however – in parts of the Ypres Salient, towards the coast of the North Sea, or on the French front south of the St Mihiel Salient – a tacit ‘live and let live’ system had developed that depended upon the recognition that, despite the war, everyday military life needed to go on. Typically, the morning and evening were marked by soldiers formally ‘standing to’ and manning the parapet in case of enemy action. Often accompanied by a wild fusillade of fire to announce their presence and intention, once duty was done, and the enemy suitably warned, it was usual for soldiers to go about their business, cleaning their rifles, sprucing themselves up as far as was possible, cooking food and repairing trenches – whatever was necessary. This was accepted and understood by both sides.

In some cases, the system went beyond simple grudging acceptance. As the war developed, and along with it a growing sense of alienation from home in many soldiers, a level of empathy and understanding developed between the opposing nations. This manifested itself in simple tricks, sign boards and the exchange of humorous greetings – such as machine gunners finishing off the traditional ‘shave and a haircut’ seven-note couplet sounding the two notes ‘five bob’ with their weapons, typical of the gallows humour that abounded on all sides. The possibility of trade – lobbed tins of meat or other foodstuffs – is also recorded, and this took place in closely confined locations such as the feet-apart trenches of Quinn’s Post in Gallipoli. For the British on the Western Front, a mythology arose that considered some of the armies of the German nation states to be more docile than others. While the Prussians were seen to be the most aggressive, those from Saxony or Württemberg were thought to be more willing to accept the status quo of trench life.

All of this suggests that from mid-1915, trench warfare had become accepted as the norm – despite what High Command had to say to the contrary. With everyday life recalibrated to accept the peculiarity of life in the trenches, humour asserted itself. As such, trench journals were produced by all sides that tapped into this new level of consciousness. Trench journals became a phenomenon of the war; produced at a variety of levels within the army, official and unofficial, they were a means of building a unit or regional identity, and of letting off steam. Often they were produced close to the front line in battalion headquarters. The most famous is The Wipers Times (and its successors ‘New Church’ Times, Somme Times and BEF Times), produced within the ruins of Ypres by officers of the Sherwood Foresters, and its stoic humour has become legendary. Three issues of the ‘New Church’ Times, bought for the princely sum of 10 francs each by Gunner Harry Gardner of the Royal Field Artillery, are illustrated.

Many other versions were produced by individual battalions: The 5th Glosters Gazette, for instance, or The Mudhook, produced for the Royal Naval Division. Together, these masterpieces provide rare glimpses of the black humour of the trenches, and of the stoicism of the men who served there.