1

A Noble Tradition Recently Suppressed

The text is called Treatise of the Hidden Chamber. Its contents line the walls of a meandering subterranean passage tomb from 1470 BC attributed to the Egyptian pharaoh Thutmosis III.

The text is a faithful copy from an original account compiled a thousand years earlier and provides instruction on how to proceed into the Otherworld, a place as real to the Egyptians as the physical world. However, unlike the physical world, which is governed by time and decay, this parallel place exists outside of time; it is present and eternal and simultaneous with the physical, like two serpents entwined around a pole. The Egyptians called it Amdwat.

The Amdwat interpenetrates the world of the living. It is the place from where all physical forms manifest and to where they return. It is an integral component of birth, death, and rebirth. Only through a direct experience of the Amdwat can a person fully grasp the operative forces of nature, the knowledge of which was said to transform an individual into an akh—a being radiant with ‘inner spiritual illumination.’

All these instructions neatly cover the walls and passages and chambers of Thutmosis’s resting place. There’s just one problem—the text explicitly states how the experience is useful for a person who is alive: “It is good for the dead to have this knowledge, but also for the person on Earth. . . . Whoever understands these mysterious images is a well-provided light being. Always this person can enter and leave the Otherworld. Always speaking to the living ones. Proven to be true a million times.”1

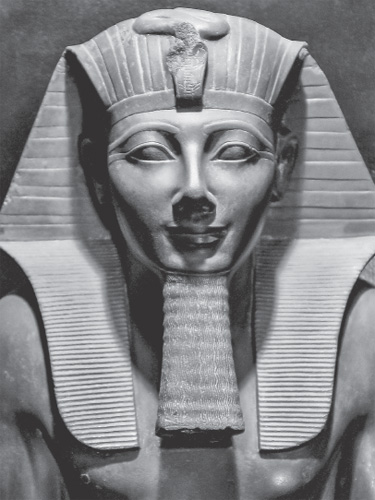

Thutmosis III.

Then there’s the tomb itself, an unusual one, to say the least:

- It comes complete with a well, a redundant feature for a dead person.

- Its central feature is an oval sarcophagus of superlative craftsmanship, and yet Thutmosis’s mummy was found in the temple of Hatshepsut, where the pharaoh had earlier built himself a mortuary temple.

- The main chamber is aligned to the northeast, the direction associated with enlightenment and wisdom in esoteric philosophy.

- The complete text of the Amdwat is the first one of its kind in the Valley of the Kings, and yet despite the pharaoh’s extraordinary accomplishments, it was painted onto the limestone plaster in a simplistic style uncharacteristic for a ruler of his magnitude.

Very odd indeed.

To understand ancient Egyptians you have to think like ancient Egyptians. These people held an unshakable belief that everything that exists in the physical plane is a mirror of processes already taking place in the metaphysical. As above, so below. Consequently, much of their writings carries two meanings: one literal, the other allegorical or metaphorical. But when Victorian archaeologists saw inscriptions covering the walls of a pharaoh’s resting place they interpreted them as serving a literal funerary purpose because, from their point of view, these subterranean chambers were taken for what they were: repositories for dead people, despite repeated absences of evidence of burial, or instances of the mummies being found elsewhere—as in the case of Thutmosis III.

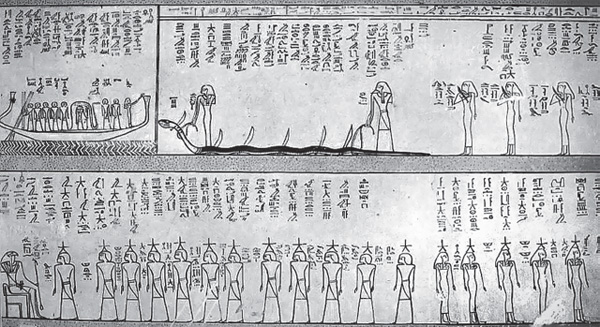

A portion of Treatise of the Hidden Chamber.

To the Egyptians, however, a tomb was considered a place of rest but not necessarily a pharaoh’s final resting place. And in much the same manner, experiencing the Otherworld did not require a person to be dead. Rather, evidence shows that after undergoing a secret rite of initiation, the candidate was roused from a womblike experience and proclaimed “raised from the dead.”

This was the concept behind living resurrection, and it wasn’t limited to Egyptian belief. It was understood by Mysteries schools, esoteric sects, and shamanist societies the world over, from China to Arizona. Gnostics of the early Greek era describe this sacred ritual as an experience that disclosed to its practitioners insights into the nature of reality. The author of a Gnostic gospel titled the Treatise on Resurrection, written in the early second century, categorically states, “Do not suppose that resurrection is a figment of the imagination. It is not a fantasy; rather, it is something real. Instead, one ought to maintain that the world is an illusion, rather than resurrection.”2 The anonymous author goes on to explain that to live a human existence ordinarily is to live a spiritual death, but the moment a person experiences living resurrection is the moment they discover enlightenment. “It is . . . the revealing of what truly exists . . . and a transition into newness,”3 and anyone exposed to this while still living became spiritually awakened.

Such a concept is at odds with the manner in which resurrection has come to be portrayed, particularly after the rise of Catholicism. In fact, a text from the same codex, the Gospel of Philip, goes so far as to ridicule ignorant Christians who literally believe that a physical body can be resurrected after dying.4

So, how did people experience living resurrection? Why did so many choose to put themselves through its rigorous ritual? What did they hope to gain in daily life by rising from the dead? And why was this philosophy banned and its adherents murdered by the millions by prevailing religious forces?