4

Early Followers of The Way

The removal of evidence of earlier crucified, atoning god-men by fundamental Christians sought to deny the ancient roots of Jesus’s story in order to exalt singular status upon the new, Catholicized hero. But alas, the idea had long been in vogue.

Sumeria, circa 2000 BC: Damuzi/Tammuz, shepherd-god who retires to a sacred mountain to contemplate true holiness, then rises from the dead.

Phrygia, circa 1170 BC: Atys, atoning god-man suspended on a tree, is buried, rises again to be revered as a messiah.

Tibet, circa 700 BC: Indra, atoning god-man, born of a virgin of black complexion, walks on water, predicts the future, is nailed to a cross, and rises from the dead. His followers were called Heavenly Teachers.

Nepal, circa 622 BC: Iao, god-man, nailed to a tree, rises from the dead.

Java, circa 552 BC: Wittoba, god-man, nailed to a tree, and symbolized by a crucifix.1

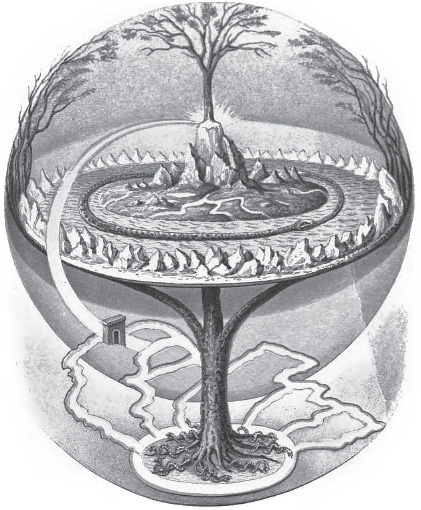

From Phoenicia to China, the pagan world celebrated the hero who crosses into the Otherworld as a ‘dead’ man, only to rise as a god and become an example of an enlightened being walking the Earth. Five hundred years before Jesus, even the Greeks were enacting a morality play of the life of Prometheus, the atoning god-man of the Caucasus who rises from the dead after being nailed to an upright beam of timber with extended arms of wood. The symbolism is very clear: the hero has developed knowledge of the lower, middle, and upper worlds, represented by the roots, trunk, and fruit of the world tree. He has returned ‘christed’ or spiritualized, in control of the four elements that sustain the world, each represented by the equal-armed cross.

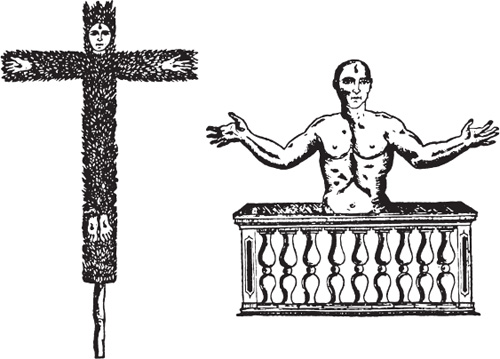

In his Alphabetum Tibetanum of 1762 the monk Augustinus Georgius lists two images of Indra as depicted in Nepal. One shows the god-man affixed to a wooden cross covered in rich foliage, with only the face, hands, and feet visible, the latter pierced as though having been nailed to what amounts to a Tree of Life (the resurrected Norse god Odin is similarly hung on Yggdrasil, the tree of life). The ensuing image depicts Indra’s upper torso rising out of a box.

Crucified, resurrected god-man Indra. From Nepal.

Yggdrasil, the World Tree, to which initiates were said to be ‘nailed’ after successfully completing initiation into the Mysteries.

Regardless of whether they were inventions serving a moral purpose or real-life individuals—and many cultures assert they were real—these heroes were merely reenacting the regenerative cycle of nature. Global traditions show again and again how the rebirth of the sun as king was celebrated for three days after the winter solstice, when his accouchement with the Queen of Heaven—the Celestial Virgin—brought forth the infant savior in the first minutes after midnight on December 24. Indeed the sun does appear to stand still on the same place along the horizon the three days around the solstice before reversing its course. The light overcomes the dark of winter and the rebirth of life and land is ensured for yet another cycle.

As for the hero, he or she undertook a ritual journey corresponding to the rhythm of the reborn sun—people like the god-man Adonis, who was celebrated on December 25 in the temple of Jerusalem long before the time of Jesus.

From Native American rites of passage to the pilgrimages of Chinese seekers, the oldest rituals around the globe followed a near-identical prescription. Typically the quest began in a remote location, a place of solitude conducive to inner contemplation, followed by a period of sensory deprivation inside a secluded environment where, immersed in the cosmic world, initiates became aware of the purpose behind the universe they inhabit. Having arrived at a state of self-realization, they discovered the divine within themselves and returned to the body with a more informed view of doctrines to be adopted in daily life. And the synonym by which practitioners referred to the process was ‘The Way.’

These individuals did not die a physical death; they merely shed their ignorance of the laws of life by successfully crossing into the Otherworld, returning with a discovery of great significance that illuminated them immensely.

NATIVE AMERICA

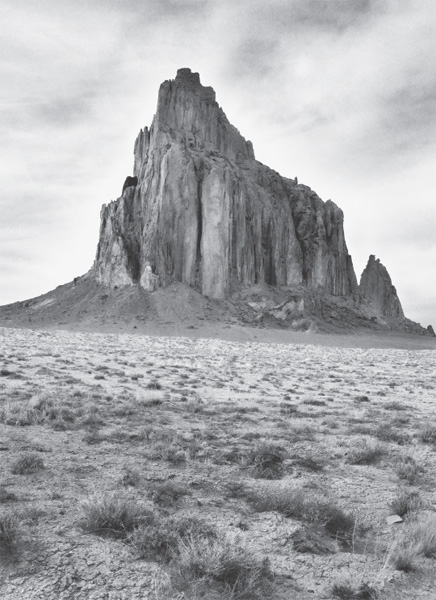

Sacred mountains occupy a central theme in Native American folklore as doorways to and from the Otherworld. They were seen as universities from whom they sought the vision of guidance. In New York State, Mount Marcy was originally called “the Great Mystery” by the Iroquois, while in New Mexico, standing high above the flat desert like a vitrified guardian angel, Tsé Bit’a’í is sacred to the Hopi, to the Navajo (who call it Naat Ani Néz), and before them, the Anasazi, for whom it was also the center of their creation myth. These spiritually attuned people were said to have alighted at this very location from the Otherworld, the dark peak marking its gateway.

Tsé Bit’a’í is as sacrosanct to these cultures as Mount Kailas is to Hindus, Buddhists, and Jains. No one is permitted to climb it. Shamanic flights into the Otherworld took place over the course of a night inside the crevasses around the base of the near-vertical breccia. Perhaps it is for this reason that its name translates as “rock with wings.”

Although the Anasazi have long since departed for the next world, to the south, the Tewa still perform ceremonies at Tsikumu, a sacred mountain near their pueblo. Like so many Pueblo shrines, Tsikumu is visually disappointing but powerful of presence, being as it is the Tewa’s portal into the Otherworld, from which they claim to have emerged long ago. Here initiates work with an energy called po-wa-ha that allows them to flow from this plane of reality to the Otherworld and back. The tradition is timeless, based on ritual handed down from earlier, nameless people.

Tsikumu is not a lone doorway but the center of an orderly geodetic cosmology that includes the Tewa Valley’s most prominent feature, Black Mesa, where there exists a ritual cave marking another entry point into the Otherworld, and where long ago there resided a family from a race of giants.2

In Southern California one of the best-documented access points into the Otherworld is the sacred hill Cuchama, meaning ‘exalted high place.’ For as long as tribal memory can recall, it has been a spiritual sanctuary where boys, upon reaching manhood, and following initiation by the elder, would be sent on a solitary vision quest in preparation to discover the Superior Man within. Completion of the ritual took place in darkness on the summit or inside its sacred cave, which appears to have been artificially sculpted. Solitary, silent, and free from all self-seeking, the candidate was left to “the worship of the Great Mystery.”3

During their journeys into the Otherworld, initiates describe being “met by Shining Beings,” shown their origins before incarnation, given special knowledge, and offered guidance concerning the path they’d chosen in this particular lifetime. Upon descending the mountain and returning to the tribe suitably enlightened, each individual was declared a “new-born one.” As a mark of his newfound clarity of vision and spiritual resurrection, the individual was bathed before entering into meditation for four days, eating sparingly, and avoiding meat for several months around the period of initiation. He was also encouraged, after marriage, to help transmit the esoteric teachings to others.

Tsé Bit’a’í, portal to the Otherworld for the Anasazi, Hopi, and Navajo.

In the Great Lakes region, the Naudiwessi performed a ritual in which the candidate came to be admitted into “the friendly society of the Spirit” by being put through a pretend death—by ingesting a seed that made him drop to the ground motionless as though he’d been shot, only later to be reawakened by previously initiated tribesmen pounding their fists on him and returning the bewildered man to full consciousness. A similar, albeit gentler ritual by the Ojibway, the Dakota, and the Sioux involved the candidate being knocked to the ground and resurrected by a blow from a soft-skin medicine bag.

The initiation ceremonies in the southwestern corner of the North American continent appear to be continuations from a race of prehistoric people said to have been of very tall stature. Traditions assert that this race of giants moved from the north in remote times, and indeed a giant skeleton was discovered by Spanish Jesuits in 1765 near the Mission de San Ignacio. The ribs alone measured two feet, making this individual eleven feet tall. A second skeleton, measuring over nine feet tall, was found by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the 1920s in Lompoc, and was claimed by a tribal elder to be a remnant of the race of giants called Allewani, from where the mighty eastern American river Allegheny derives its name. In addition to the unusual skeletons, during the last years of their tenure in Southern California, the Jesuits also discovered ceremonial caves bearing painted images of men and women dressed in clothing not typical to local native cultures.4

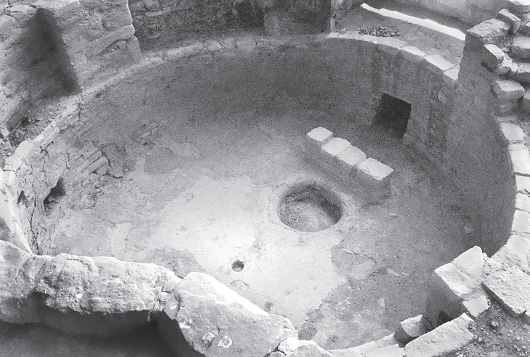

Being more attuned to the land, the nomadic tribes of North America rarely built permanent temples because, to them, the whole landscape was sacred. Rather, they perceived hot spots of energy on the land where an intimate conversation can be initiated with the Otherworld. Hopi legends describe how contact between these two worlds is made umbilically through a hollow reed called sipapu. This reed would appear inside a kiva—the Native American equivalent of a temple—for which a small, round hole was made beside the fire pit, allowing the ancestors to emerge in front of those in attendance, and, following a closed ritual ceremony inside the kiva, a conversation was initiated between the mortal and the imperishable. The same concept is recorded in the Japanese creation myth Nihongi, which mentions how a reed-shoot was produced between heaven and earth allowing communication to be established between the two.

Sipapu hole inside a kiva.

As the Mohave people once pointed out, knowledge gained through such encounters was not a thing to be learned but acquired by each person according to the visions received while in contact with the Otherworld.5

AUSTRALASIA

Initiatory rites consisting of a simulated death and resurrection were generally offered to youths reaching the point of puberty and, like those performed by the Wonghi and Ualaroi of Australia, involved a secret ritual observed strictly by a group apart from the rest of their culture who’d already undergone initiation. During the ritual, the youths came face-to-face with a spirit being called Daramulun who took them into ‘the distance,’ cut them up, and reconstituted them into a new, pure form.

One of the more dramatic initiation ceremonies was performed by the Murring, in which a medicine man was laid down in a grave, lightly covered with sticks and earth, and made to resemble the spirit of rejuvenation. While motionless novices were placed beside him as though in a trance, the medicine man acted as the protective spirit guide while the novices traversed the Otherworld. Upon their return, they all rose together as if from the dead.

In northern New Guinea, the Yabim, Bukaua, Tai, and Tami constructed a special temple, about one hundred feet in length, in a remote part of the forest specifically for such an occasion. It was modeled in the shape of a mythical monster, with a mouth or entrance forming the tallest part of the building, which then tapered toward the rear—much like the earthen barrows of Britain and northern France, which were used for similar purposes. A betel palm formed the axis of the structure and at the same time represented the backbone of the Great Being. The initiate stayed in the hut for months if necessary, shunning all contact with the outside world, until reemerging resurrected from the belly of the beast.

In the Indonesian island of Ceram the initiate was placed inside a wooden shed with a bloodied spear thrust through the roof, to symbolize the removal of his head by a spirit, so that the rest of his body could be taken into the Otherworld to be regenerated and transformed.6

A vestige of these traditions was still evident in the mid-nineteenth century on Mana Island in New Zealand, where existed a whare whakairo (a Māori sacred house) named Kaitangata—‘eat man’—accurately describing the purpose of this sacred abode as a place where one comes to be symbolically de-fleshed. Māori mythology identifies Kaitangata as a mortal man who marries the supernatural female Whaitiri; however, he is also a son of the immortal star-god Rehua, an entity who possesses the power to cure the blind—those who ‘do not see’—and revive the dead. This personage is identified with Sirius.

What is astonishing about such rituals throughout the Pacific is how they are near-perfect adaptations of the Osirian myth of the Egyptians in which the god-man is placed inside a large box, cut up into pieces, reconstituted, and in one version, resurrected as a palm tree.

PERSIA AND THE CULT OF MITHRA

Long before a group of mystics called Parsis fled persecution and settled in Mumbai in the tenth century, their predecessors, the Zoroastrians, preserved a marvelous religious heritage throughout Mesopotamia, and later, Persia. Their scriptures are replete with references to sacred mountains where people disappeared for long periods of time to seek contact with the Otherworld. The most referenced is Mount Ushi-darena, a name derived from hûsh dar, meaning ‘to illuminate and sustain by divine consciousness.’ According to Avestan literature this high peak marks the location where wisdom is received by a person in a receptive state of mind. Returning pilgrims were described as possessing khvarenah, ‘divine glory.’

The earliest accounts of spiritually connected places in Persian Sanskrit literature state that a golden tube protrudes from the summit of sacred mountains such as Mount Sokanta, extends deep into the earth, and stretches out into space—not unlike the description given by Native Americans and Japanese. This energetic conduit is said to allow nature’s forces to instill a state of superabundant consciousness in the recipient. Strangely enough, in one of those special moments where science accidentally validates legend, magnetic tubes linking the Earth with the sun and opening like portals throughout the day were proved to exist by NASA in 2008.7

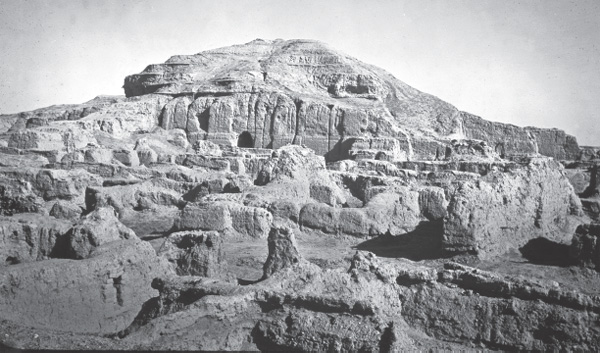

One of the most ancient resurrection traditions in Mesopotamia was performed every year during the winter solstice festival of Akitu, when the god of fertility, Marduk, descended into the Otherworld before rising triumphantly back into the material world three days later. The human reenactment of this regeneration was performed by the existing ruler, who was disrobed in public before being confined in the mountain—a man-made stepped pyramid called a ziggurat.8 No wonder, then, that ziggurats were considered to be the meeting place between gods and men, the threshold between tangible and unseen.

Ziggurat of Ur, virtually indistinguishable from a sacred mountain.

These colossal, mud-brick structures have not fared well over time, their unstable condition making it impossible to validate the existence of internal chambers that may have been used for the ritual of living resurrection. But what is known is that each structure was crowned with a temple at the summit whose inner chamber could only be accessed through an impractically small opening, either to make a person stoop low in humility or to limit the amount of light penetrating the space and thus enhance the sensory deprivation inside the chamber. The thread of the story then gets lost in Babylonian culture when, around 2000 BC, there appear the roots of what would become the religious philosophy of Zoroastrianism.

Zoroaster sought and attained illumination at Mount Ushi-darena where he mastered the secrets of nature. His disciple Asmõ-Khanvant was likewise initiated, whereupon he too attained spiritual wisdom. One of the fruits of these insights came in the form of the Avesta, the sacred literature of Zoroastrianism. Its most ancient core, the Gâthâs, claims to provide the pathway to the Otherworld. Clearly, for this to have been written implies Zoroaster traveled there and returned with significant perspicacity. His teachings certainly cultivated an enormous following, which elevated him to messianic status, so it may come as no surprise to hear that Zoroaster was saved from death in infancy, retired to a wilderness cave to contemplate true holiness, was crucified, and resurrected.

A central theme of Zoroastrianism is the ancient and highly influential Aryan cult of Mitra. The name in Avestan means ‘causing to bind.’ So to walk in the footsteps of the Mithraic Mysteries is to seek unity with the source of all things—hence why this god is associated with divine wisdom. He is also the guardian of the Bridge of Separation, the route that connects the soul with the Otherworld.

Mitra appears in Vedic literature around 2000 BC as a rejuvenating god, often paired with a female counterpart named Varuna, forming the principle of paired opposites like the sun and moon. He was a solar chariot god, partook in a sacred meal, and his act of self-sacrifice was an example for others on the quest to find redemption for the soul, and thus victory over its earthbound existence.

Mitra’s symbolic color was red—the color of twilight prior to sunrise—and every December 25 he was reborn from a rock. A bright light in the sky heralded the event, drawing shepherds to the location whereupon they are informed of the importance of the event by a divine messenger. Other unspecified gods are also in attendance. His life was then celebrated a second time at the spring equinox.9

Mitra was so influential throughout Persia that he was absorbed into the teachings of Zoroaster as Mithra. In this cult, aspirants immersed themselves in an underground stone chamber, either natural or man-made, where they underwent regeneration after being enclosed within a kind of boat or retaining vessel for a predetermined amount of time. Initiation into the Mysteries requires the hero to enter a dark world—a cave or chamber representing the primordial womb from which all life originates—to sacrifice his animal-material urge if his spiritual soul is to be released and reborn.

The god-man Mithra himself was said to have entered a ritual cave and killed his animal-material self by plunging a knife into the spinal cord of a bull, causing a cornucopia of wheat and wine to be released and offered to the sun. The tale later resurfaces in Minoan Crete, where the hero Theseus undertakes a journey through an underground labyrinth to successfully slay his animal self, the Minotaur.

The philosopher Porphyry of Tyre writes that temples associated with this cult were mirror images of the original grotto consecrated to Mithra somewhere in the mountains of Persia. Porphyry also notes how, during initiation, the candidate was presided by the moon or a lunar deity—which itself was equated with a cow or a bee, as were the priestesses in attendance who were addressed as bees. Preparation began with baptism followed by severe discipline of the body, sometimes by as much as eight different types of trials in which aspirants demonstrated their courage, mental fortitude, and mindfulness. All these tribulations were intended to facilitate the candidate’s peaceful regeneration in paradise. When they successfully reemerged from the door of the cave or chamber, initiates were deemed reborn from a heifer, declared resurrected, and thereafter represented by a bee.10

Such traditions must have endured for a considerable time because evidence of their practice was discovered by Alexander the Great when he vanquished Persepolis in 330 BC. Alexander visited a temple built by the Persian king Cyrus, a ziggurat intended as the king’s tomb but with the notable exception that there was no evidence of a body ever having been interred. Legends state that Cyrus was actually buried under his ziggurat, which itself is located in the midst of an area the Persians called Paradise. On the summit stood a rectangular building with a chamber at its heart, accessed by a very narrow passageway. It was in here that Alexander found a golden bed, a trough or ritual sarcophagus made of gold, and an abundance of garments.11 Clearly these items were superfluous to a dead person, giving the impression that the chamber was meant for a living being expecting to return to daily duties. More to the point it suggests that for several thousand years a ritual associated with living resurrection was conducted in this part of the world.

As the influence of Mithra subsequently flowed westward he came to be associated with the constellation Orion, thus linking this god-man with Osiris. Inevitably his cult reaches the shores of the Mediterranean and enters the Roman Empire and takes on yet another subtle name change: Mithras.12

The cult of Mithras vied with early Christianity on equal terms for five hundred years before one of its adherents, the emperor Constantine, replaced the hero of the story with Jesus, at a stroke elevating this newcomer from mere mortal into resurrected god-man. And yet hundreds of years before Christianity, Mithraism already embraced the theology and rituals now cherished by Christianity, among them the imbibing of wine as a metaphor of sacrificial blood, the partaking of a small loaf of bread or wafer bearing the sign of a cross (the Eucharist), and a last, sacred supper. To counteract claims of usurpation, Catholic writers claimed the devil, knowing in advance of the coming of the Christian rituals, imitated them before they existed in order to denigrate them.13 Early church writers additionally falsified the original story, going so far as to replace the gods present at Mithras’s birth with Magi, which inadvertently acknowledged the Persian origin of the myth while at the same time demeaned the Magi by showing them idolizing a Christian infant.

Much of what is known about Mithraism comes from late Greek and Roman accounts in the eastern Mediterranean and from temples in southern Italy that survived Christian persecution. Neophytes wishing to join the Mithraic Mysteries entered as frates (brothers), and underwent a period of observation before being initiated through seven levels, the names of which survive in Latin: Corax (raven), Nymphus (secret bride), and Miles (warrior). These preceded the adept levels, each of which was blessed with an anointment of honey: Leo (lion), Perses (laurel), Heliodronus (messenger of the sun), and finally, Pater (father).

The titles are highly suggestive of the function and responsibility inherent in each degree. For example, a Perses was defined as a ‘keeper of the fruit’ and was associated with the moon, while its totem—the scythe—identifies the title with Perseus, the god who uses it to behead the monster-adversary Medusa, thereby sealing the candidate’s maturity and the fruits of wisdom that come from such an awakening.14 Writing in De Abstinentia, Porphyry notes that the Mithraic ritual was open to both sexes, with male adepts called lions, and women, lionesses. The contemporary cults of Cybele and Attis were also open to women. Study and training were intense, harsh, and difficult with every individual’s actions under close scrutiny. Candidates were bound and blindfolded during a swearing-in ritual in which they declared to uphold the secrets about to be entrusted to them. And if they agreed to the terms they were tossed over a river or ditch filled with water. An adept armed with a sword would then cut their bonds and remove the blindfold. Another part of the ritual involved the blindfolding of a candidate inside a sarcophagus resembling a bathtub.

Mithraic temples were typically small, capable of housing no more than a handful of selected people, with the entrance generally placed in the west and the altar in the east. The nave was lined on either side with an angled bench where candidates reclined before being administered the final meal; in southern Europe and coastal Syria these unusual benches were called praesepia (cribs). The last thing reclining initiates gazed upon as they fell into unconsciousness was the Milky Way painted upon the arched roof of the temple, along with a ladder of stars with souls ascending and descending.15

Such Mithraea were built underground, leading the writer Tertulian to note in De Corona the irony that Mithrasians venerate a god of light in “what is truly a camp of darkness.” Mithra was a god of balance and naturally his seat was the equinox. So it is not surprising that the Mithraea that have survived destruction reveal a small hole in the ceiling of the temples to allow a ray of light to shine upon the altar at the equinox.16

Murals inside one Mithraeum in Ostia depict initiation scenes in vivid detail. Members of the higher degrees are shown taking the sacred meal while paters—the sole repositories of sacerdotal knowledge—preside over the ritual. Another mural features a candidate kneeling on one knee and swearing an oath, just like the ritual in modern Freemasonry. Another shows the candidate on both knees, with arms crossed over the chest, in what is called the Osiris position.

Altars typically depicted the scene of Mithra stabbing a bull from whose wound sprout three ears of wheat. Since Zoroastrian mythology also assigns the bull to the god of darkness, this symbolic icon encompasses the aim of the ritual that leads to the ripening of the soul and its latent fertility as a result of its rebirth.

Such icons were accompanied by the figure of a divine virgin holding an infant with her left hand while her right holds a stick with which to pluck the fruit from the tree of wisdom standing behind her. A veil covers her head, around which shine seven rays of light.

Needless to say, Mithraism became the prime quarry from which Catholicism plundered its foundation stone.

Ziggurat of Cyrus the Great. No body was found inside.

The geographic area of Persia bears the imprint of some of the world’s oldest civilizations, specifically the Mesopotamian. It is therefore highly likely that Mithraic rituals were themselves a residue of an even older culture, such as the Scythian, which existed in and around the Carpathian region east of the Black Sea and migrated southeastward.17 For one thing, the existence of ancient precuneiform writing, often attributed to Mesopotamia, and which precedes Sumerian cuneiform, was found one thousand years earlier in Transylvania;18 even the very name of the Sumerian capital, Ur, comes from the Scythian word for ‘Lord.’ To the point, at the center of Scythian culture was its royal priestly caste, the Tuadhe d’Anu, also referred to as the Sumaire and Lords of Light, who were renowned for their transcendent powers, particularly their ability to access the highest state of consciousness called Sidhe,19 that same out-of-body state practiced by those masters of the initiatic arts of India, the Siddhis. To this effect the Scythian lords, the Tuadhe d’Anu, built colossal earthen mounds or kurgans atop secret stone chambers, a number of which contained empty sarcophagi.

One such kurgan is Sengileevskoe-2 near Strovopol, Russia. Excavations in 2013 revealed a secret rectangular chamber in which were buried gold artifacts of superlative quality. Of specific interest are three gold cups containing a black residue, analyzed as a brew consisting of the narcotic opium, impregnated with smoke from cannabis, which would have been burned to create a vapor-bath inside the chamber.20 But it is the decorations on the cups that reveal much about the ritual that took place here, for they show highly detailed and dramatic scenes of animals and humans fighting and dying, not to mention a depiction of a bearded elder stabbing a younger man in the spinal cord, a feature identical to the later Mithraic scenes of the hunter stabbing the bull in exactly the same anatomical location. Incidentally, both ‘hunters’ wear the same Phrygian cap. Such graphic images represent the rite of passage into the Scythian Otherworld, which culminates in the ritual sacrifice of the immature younger self.

Scythian initiation cup.

THE HOME OF ELF

Tracing the concept of the Otherworld to Mesopotamia brings us to the true nature of the elf.

Five thousand years ago the word El identified a ‘shining one,’ referring to an ascended person, a god-man, or a being of angelic status. By the time it reached Saxony, the name had morphed to elf, whose abode in Norse mythology is Alfheim, which transmigrated to ancient Scotland as Elphyne and Elphame, literally ‘Elf-home.’

In early Nazarene philosophy this Otherworld is likened to a heavenly kingdom, and neatly explains the misinterpreted initiatic phrase spoken by Jesus, “Except a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of heaven.”21 Initiates of this matrilinear heritage—which included such notables as Lilith, Miriam, Bathsheba, and Mary Magdalene—were associated with high wisdom as well as a messianic bloodline.22

This is the same realm to which Hylas, hero of Apollonius’s Greek myth Jason and the Argonauts, is transported by the water nymphs, a domain he figuratively enters by way of a sacred pool that constitutes daleth, the very doorway to the Light. What Apollonius of Alexandria is conveying in his epic from 250 BC is the demise of ego and desire, a metaphoric death, from which one is reborn so as to become focused in a different dimension. As an initiate himself, he would have known.

In Kabbalistic tradition, daäth (whence death) means ‘higher knowledge,’23 and its location on the Tree of Knowledge equates to a kind of bridge linking the principles of generation and regeneration, an interface between two opposite yet complimentary states of being, a position no doubt supported by the ancient Egyptians, whose terms for ‘tomb’ and ‘womb’ were interchangeable and mutually supportive as routes to a specialized knowledge that can only be truly grasped while in the Otherworld.24

In so many world myths and tales describing the path of the initiate, water marked the symbolic boundary between the material world and the home of elf; it was the first step toward entering the transcendental state, illustrating the importance of baptism as the first stage of initiation. In this state, one resides within this world while not being of this world, by virtue of one’s higher spiritual and intellectual achievement. In a gnostic sense, it is a living beyond the normal state of mortal life. The color representing this state was green, the color of nature, and later, the color attributed to elves and to Otherworld figures such as Osiris, Briddhe, and Siva; it was also the Gaels’ color of death, of Venus and fertility, hence why it is not ritually used in the Catholic Church, who further debased the sacred connotations of this hue during the Middle Ages by associating it with envy.

JAPAN

Just as the Cochimi and Yuma tribes venerate Cuchama as the “exalted high place,” so the Japanese pay homage to Fuji-no-yama, the “Honorable Mountain.” For centuries pilgrims have undertaken initiation on this and other Japanese sacred mountains to find shugendo—The Way—which they say develops the spiritual power dormant in every individual.

The word shugendo is highly descriptive: shu is nurturing the enlightenment of an initiate’s inherent divine nature; gen, his innate realization; and do, the attainment of nehan, the equivalent of nirvana. Here we find parallels to Egyptian Mysteries, for Shu is also one of the Egyptian primordial gods, the mediating entity between what is above and what lies below. The Egyptians believed if Shu failed to hold his son Geb (God of the Earth) and his daughter Nut (Goddess of the Sky) in perfect equilibrium, life simply could not be created.

Since one of Shu’s grandchildren is the god-man of resurrection, Osiris, it is interesting to note that one interpretation of the Japanese word fuji is ‘everlasting life,’ a core objective of the soul’s contact with the Otherworld.25

Perhaps the most important sacred mountain in the practice of shugendo is Haguro. In ancient times, during the processional walk along its thirty-three primary temples, initiates reflected on the nature of the mythical couple who created the world, and upon reaching the summit they claimed to “enter the mountain” and “depart for the Otherworld.”26 This belief is still maintained by followers of the mountain sect of Shinto (the religion of Japan), who believe that by ascending sacred mountains one attains spiritual purification between the body and the divine. To reinforce the point, it is customary for pilgrims to wear white garments. And although there is no known record of a ritual cave on Fuji, adepts do refer to its near-perfect circular crater as “the sanctuary.”

Japan’s oldest mystical practice, Shinto, has its roots in the Shén Dao of China, the ‘philosophical path of the spirit,’ better known by its abbreviated name, Tao.

Arguably the most sacred of all Japan’s Shinto shrines is Ise Jingu; in earlier times its wisdomkeepers were the jinni, teachers who embody the knowledge of the spirits.27 Ise Jingu’s ancient sanctity and importance is described in the Kujiki-72, Japan’s oldest prehistorical text, whose seamless doctrine of history and metaphysics impacted Japanese esoteric thought over millennia. This controversial narrative was discovered in the shrine itself.

One of the many stories found in the Kujiki-72 describes the descent of the heavenly messenger Nigihayahi, who brings with him ten treasures in the form of sacred teachings. Nagihayahi is instructed by his superiors that, should his body or those around him ever be troubled or pained, by applying the teachings, the ‘dead’ will be brought back to life. Some of the titles—such as the Jewel of Life, the Jewel of Resurrection, and the Ceremonial Cloth of the Bee—tellingly convey important initiation practices.

Another central component in the text is a kind of divine virgin by the name of Amaterasu. As well as being a kami (a god or essence whose energy permeates nature and generates all phenomena), she is also the female representation of the sun, and thus all knowledge resides within her. She is married to the god of the moon, but when he falls out of favor, Amaterasu withdraws to a cave and darkness befalls the Earth. However, she is soon reminded of her responsibility to foster fertility and reemerges to bring light to the universe. It’s at this very moment that she merges with her male kami and becomes a single entity by the name Amateru and descends to the location that, in time, becomes the shrine of Ise Jingu. Residing in this sacred site, this single woman-man teaches the mechanics of Creation called Ise-no-Michi (Way of Ise), and its teachings ensured the alchemical marriage of the initiate.

The Way of Ise required long and careful study if it was to be adopted correctly in daily life. This was carried out within Izawa-nomiya, a secluded and restricted area of the shrine presided by a fraternity of adepts who lived as a separate entity to the rest of the complex. Together with two attendant temples it formed a three-mile-long ritual environment called Place of the Way.28

The methods of the Kujiki-72 are complex ritual affairs, compounded by an ancient Japanese text only decipherable by a handful of scholars, and further obscured by allegory and metaphor. At its core is the description of a universe regulated by five constitutions comprising seventeen Ways. Its cornerstone is the secret Way of Heavenly Being, which itself comprises the secret initiation Michinoku (Depth of the Way). It is perhaps the only known surviving instruction given to initiates preparing for the final resurrection rite. Any individual who embodies this constitution comes to embody the Way of the Protector and, if they so choose, they adopt the Way of the Watchtower and become a teacher to incoming flocks of neophytes.

One further piece of information that reveals the original shrine of Ise Jingu to have been a location where the secrets of the Otherworld were taught and practiced concerns Amateru’s revelation: namely, that in order to follow the example of an individual who’s harmonized the masculine and feminine and become a god, it is necessary to consume chyomi-kusa, the “thousand-year plant” that grows on the summit of Mount Fuji, whose roots make one virtually immortal. Maybe the inference is allegorical, that to climb the summit of the holiest mountain in Japan is to seek the Tree of Life, as practitioners of Shinto do to this day. And yet chyomi-kusa follows the pattern of consuming a narcotic from a special plant during initiation, like the soma and haoma plants of Vedic and Persian initiation, both of which also grow on high mountains and are said to be inedible to the ordinary person.

Shrine on Mount Haguro.

It is not known if the name Ise is a transliteration of Isa/Isis, wife of the Egyptian resurrected god-man, however, it is known that priestesses in a nearby temple performed religious ceremonies using a rattle bearing an uncanny resemblance to the sistrum used in similar ceremonies by priestesses of Isis.29 Certainly the goddess Amaterasu, whose essence is the foundation of Ise, shares many common traits with her Egyptian counterpart: she is married to a husband-brother; they represent the cosmic marriage; her brother goes on a rampage that nearly undoes her life, not unlike the murderous Set in the Egyptian myth; she is the repository of divine wisdom; and she also oversees a yearly inundation that brings fertility to the land; in Japan this being brings the rains, guaranteeing a successful harvest of rice.

CHINA

To this very day the sacred Mount Omei and its seventy-two monasteries and shrines still attract two million pilgrims each year. Like a mirage from a distant epoch, you can see Buddhist Pure Land practitioners chanting the nianfo mantra for two hours as a trance tool for achieving their aspiration to be “reborn in the pure land”—the Buddhist interpretation of paradise, also known in Sanskrit as sukhavati (utmost joy). The ritual serves to purify thoughts and bring mental clarity so as to allow for true understanding of the sacred knowledge, a prerequisite for the pilgrim’s reemergence in the Otherworld.30 This religious ritual was often seen as a way for lay people not associated with a monastic system to get a taste of the Otherworld, an expedient method for glimpsing paradise, implying a deeper ritual was reserved for those who joined the inner groups belonging to the monasteries.

The description of the Otherworld in the sacred text Sukhavatyamrta-vyuha is practically identical to other contemporary esoteric philosophies:

In Sukhavati there is no suffering, and that world is adorned with all kinds of treasure, beautiful lotuses, and wonderful music. . . . This is an exceptional world, especially for the salvation of the unenlightened beings in the period of degeneration [the physical world], who are able to attain the enlightened state in this blessed land. . . . He or she will depart this life with tranquility and be reborn in Sukhavati.31

This philosophy, already noted on Mount Omei in AD 400 under the care of the White Lotus Society, may well be an echo of traditions performed by ancient Rishis in 2697 BC. Back then, people undertook pilgrimage to the mountain to “find The Way,” one of them being the Chinese emperor Hsuan Yuan.32 Monks such as Daoist master Zhang, who lived on the slopes of Mount Omei, were called Gentlemen of The Way and practiced meditations at magnetically charged locations such as the Celestial Altar and Celestial Pillar. Their vision quests led to Taiyi, The Way,33 and on such occasions, practitioners claimed to have observed luminous beings, much in the same way Native Americans experience Shining Beings during their initiation rituals.

Another of China’s sacred mountains, Wu-t’ai, is similarly credited as a place of pilgrimage from where individuals would return enlightened having sought the great bodhisattva Manjushri, the personification of wisdom itself. Wu-t’ai’s tradition as a place to awaken the “Great Man within” dates back millennia and served as a beacon for many illustrious Chinese patriarchs in their quest to attain enlightenment. This five-peak mountain is similarly known for its supernatural phenomena, and like China’s other eight sacred mountains, many prayer locations coincide with geomagnetic anomalies.

PHOENICIA

Historically, the Phoenician lands bordering the Mediterranean have long experienced a synthesis of Persian and Egyptian influences, the cult of the temple and its associated language notwithstanding. In the third millennium BC Egyptian traders were already traveling to Phoenicia and returning with all manner of goods, particularly cedar. Its oldest town, Byblos, is also one of the oldest in the region; its earliest structures conservatively dated to 8000 BC.

The naming of places or things in the ancient world typically followed the purpose for their existence. Byblos’s original name in ancient Phoenician is Geb-el—an approbation of Geb, Egyptian lord of the Earth. Since Geb is derived from gb, meaning ‘well’ or ‘origin,’ the location can best be described as an ‘underground repository that is the source of divinity.’ As such, Geb-el reveals much about the purpose of its temples. In one version of the myth of Osiris, the chest containing his body washes up on the seashore at Geb-el, whereupon Osiris is ‘grounded’ and, thanks to his consort, Isis, and the god of wisdom, Djehuti, he is resurrected.

The reconstitution of Osiris’s body and its accompanying ceremony was said to have been solemnized in an underground cave to the north, on the island of Aradus, which at one point was patronized by the pharaoh we met at the beginning of our quest, Thutmosis III (in whose chamber appears the text outlining access into the Otherworld by a living person). On Aradus there once existed “antiquities of a very extraordinary kind”—a pillared altar and, from the following account, what appears to be an initiatory temple complex:

About half a mile to the southward of this court are two towers, supposed to be sepulchral monuments, for they stand on an ancient burying place. They are about ten yards distant from each other, one in form of a cylinder, crowned by a multilateral pyramid, thirty-three feet high including its pedestal, which is ten feet high and fifteen square. The other is a long cone, discontinued at about the third part of its height; and instead of ending in a point, wrought into a hemispherical form; it stands upon a pedestal six feet high, and sixteen feet six inches square, adorned at each angle with the figure of a lion in a sitting posture. Underground there are square chambers of convenient height for a man, and long cells branching out from them, variously disposed and of different lengths. . . . These subterraneous chambers and cells are cut out of the hard rock.34

INDIA

On a promontory in Mumbai Harbor there stands an arresting hill inside which lies a network of sculpted caves. Named Gharapuri (city of caves), the enterprise is impressive for one very notable reason: the rock-cut architecture has been hewn from solid, hard basalt. Obviously the location was of critical importance because the workers could have worked the nearby seams of sandstone and saved themselves a huge amount of time and inconvenience. But they were adamant on this exact spot and proceeded to chip away the stone to create two groups of caves: one containing sculptures of the Hindu god Siva hewn from the living rock, the other dedicated to Buddhism.

Pandava, the hero of the Hindu epic Mahabharata, and Banasura, the demon devotee of Siva, are both credited with building this temple so that their essence may continue to live inside. But what is also notable about the cave temple of Gharapuri is the sculpted likeness of a king drawing a sword and surrounded by slaughtered infants—all boys—a scene strangely reminiscent of that described in the biblical story of Herod, and yet the Hindu version is nine hundred years older.35

In times gone by, the Gentoo used this sacred place as an initiatory temple for the purification of their sins, entering the narrow cavity from below, “too narrow for persons of any corpulence to squeeze through.”36 Thus the candidates transmigrated from this world into the womb of the Earth mother, cocooned themselves under the gaze of Siva—god of regeneration and rebirth—and three days later reemerged metamorphosed from an opening above the rock-cut temple.

Rock-cut chambers. Gharapuri (now Elephanta).

A similar rock-cut temple exists to the northeast at Mathura, in the shape of a cross, this time dedicated to Siva’s peer, Krishna.

PERU

Long before the relatively late Inca arrived in the ancient city of Cusco during the thirteenth century, a local temple called Q’inqu was already established as one of the most important spiritual places in the region, a ceremonial center featuring a natural monolith resembling a phallic lingam connected to an eroded andesite butte carved inside and out with ledges, passageways, hidden niches, stairs that lead nowhere, and a ritual chamber dedicated to an earth goddess. It is a perfect representation of the divine marriage carved from natural stone. Its forecourt is designed in the shape of a curve made from interlocking and meticulously dressed blocks divided into seventeen alcoves.

Its Quechua name means ‘zig-zag,’ a reference to a meandering pattern neatly incised into the bedrock that connects to a libation bowl at either end. The same pattern is found at sacred places throughout the world and identifies them as locations where the Earth’s natural energy pathways congregate, and where people undertook out-of-body journeys.

Q’inqu’s underground chamber is accessed by a narrow passage deliberately fashioned out of solid rock to face the equinox sunset, the direction of ritual descent into the Otherworld. The passage meanders like an S into an extraordinary space, the hard andesite skillfully sculpted into a series of perfectly flat and polished ledges where one could spend a very comfortable night immersed in a womb-like setting. Its dominant feature is a five-foot-tall altar ledge painstakingly separated from the bedrock to make a freestanding structure.

The passage then bends once more, enabling a person to exit eastward and onto a bowl-shaped courtyard, whose bedrock has been cut deliberately and painstakingly into a vertical wall at a compass angle that accurately references the heliacal rising of Venus at the autumn equinox; the southern section of the courtyard, although now in ruins, allows a view of Sirius at the summer solstice. Venus, like Sirius, was considered by numerous cultures as a star of wisdom, and specifically, as the morning star that brings periodic renewal. Not surprising, then, that Q’inqu was regarded locally as the entrance into the Otherworld.

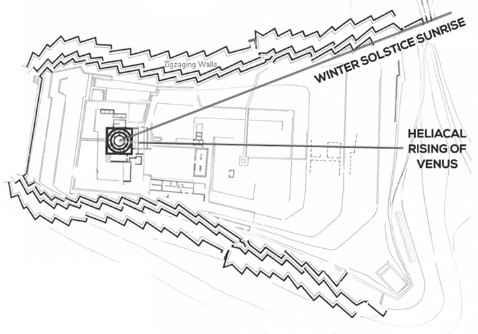

Venus and the sun are seen rising together again three months later at the winter solstice, this time at Saqsayhuaman, an impressive megalithic complex spread across fifty acres. It is a short walk from Q’inqu along an old ceremonial route, and given their shared astronomical connections it is highly likely both sites once formed part of a ritual whole.

Ritual chamber hewn out of the living rock. Q’inqu, Peru.

Saqsayhuaman’s unique feature is its serrated megalithic walls. Before the conquistadores plundered one side of the compound for building material, this unique construction, when observed from the air, took on the appearance of a bird’s wings, more so given that the site’s name in Quechua means ‘the place of the satisfied falcon.’ Although this bird receives scant attention in Andean mythology, the symbolism would make a visiting ancient Egyptian feel very much at home, where the falcon was revered as both Seker and Horus—the former as god of rebirth, and the latter as the symbolic continuation of the resurrected Osiris, whose rituals were enacted and consummated on the equinox and solstice.

The axis along the raised section of Saqsayhuaman aligns to the heliacal rising of Sirius on June 21 (winter solstice in the Southern Hemisphere), while the extreme edge of its northern wall marks the solstice sunrise. Inversely, on December 23, it is Venus that rises along its axis just before sunrise, a phenomenon that recurs every eight years, making this a perfect spot for celebrating the resurrected hero and the rise of wisdom.

Saqsayhuaman and its alignments.

A 250-mile bus ride southeast of Cusco brings you to another natural feature partly reshaped by human hands, a sandstone massif on the edge of Lake Titicaca. Once when the water level of this inland sea surrounded it, the hill was an island resembling a teardrop. The tectonic shifts that plague this region have tilted its bedrock a full ninety degrees, leaving the red stone exposed to the elements so that from the air it resembles a band of razor blades. The hill is called Hayu Marca, literally City of the Spirits, and along its facade long ago, nameless people carved a monumental portal and called it Amaru Muru. A hollow niche at the base is tall enough to accommodate a person of average height.

The work bears a passing resemblance to Egyptian spirit or false doors (which we’ll come to later). Indeed the oldest legend describes this as “a doorway to the lands of the gods,” and holds that in times long past great heroes passed through this gate for a glorious new life of immortality in the Otherworld. The doorway faces east and the rising sun at the equinox.

Amaru means ‘serpent’ in Quechua, and as with similar locations, the title identifies the site as a conduit for the Earth’s energy currents, which, together with the high content of iron oxide already present in the rock, leaves an indelible impression on anyone who ventures here. The Catholic zealots who conquered this land felt unnerved by it, so much that they called it the Devil’s Doorway; certainly less-attuned locals feel perturbed by this place and often report a blue light emanating from a tunnel inside the rock, or strange people dressed in unusual clothing emerging from it and traveling toward Lake Titicaca. One of the more enduring myths recalls the time of the sinking of the prehistoric continent of Lemuria. One of its seven Great Masters, Aramu Meru, was entrusted with a mission to bring the sacred Golden Solar Disc from the Temple of Illumination to Lake Titicaca for safekeeping. During the time of the Inca the disc was transferred to Cusco, but upon the coming of the Spanish it was returned to Lake Titicaca and placed in the Eternal City inside the lake. There may be something to this because recent archaeological finds eighty feet below the present lake level have revealed evidence of this fabled city.

But the portal into the Otherworld at Amaru Muru is not alone. It shares its design with a twin on the opposite side of the world, at Yazilikaya in Turkey, and comparing the two would lead anyone to believe they were both carved by the same artist. This vertical limestone outcrop has been incorrectly linked as the burial place of Midas, the fabled king who turned everything he touched into gold. However, the king’s body was never found here, and not surprising, given that mida is the Phrygian surname of Cybele, a local adaptation of Demeter, the tutelary goddess of the Greek Mysteries school and its related initiation rituals. At such occasions her statue was even placed in the spirit door of this sanctuary. Above it, on the summit, there is a rock-cut altar and accompanying tunnels that lead 900 feet down into the solid rock where secret initiations were conducted.

The same is true of Amaru Muru. There exist vestiges of some kind of rectangular structure on its summit, as well as a tunnel descending into the rock face on the other side of the portal, long since bricked up by the authorities lest anyone should disappear into the bowels of the Earth, because as pre-Inca legends claim, the tunnel extends all the way to Cusco.

Gates to the Otherworld: Amaru Muru, Peru (top), and Yasilikaya, Turkey (bottom).

So many examples bear common threads illustrating an art of self-realization both pursued and practiced around the world and by individuals who set themselves apart from the rest of society. It also demonstrates that the Knowledge transmitted from group to group shared a common source of now-forgotten origin. In the second millennium BC there were already recurring instances of members of an Egyptian pharaoh’s household at Saqqara being favored to join a privileged inner circle to “master secret things of the king.” One individual described being led into a restricted chamber to experience a unique ritual, after which he joyfully proclaimed, “I found The Way.”

Needless to say, at some point this reached Palestine, because two thousand years later the ritual and its accompanying expression were resurrected by the Jerusalem Church of the early Christians. One woman who was intimately connected with The Way at this time was Mary Magdalene. Her father, Syro, was a Jairus, a high priest, whom Jesus himself raised from the dead.37 This ‘raising’ into the degree of community life was part of The Way, and typically administered as a rite of passage at the age of twelve. Mary Magdalene, or more correctly Magdala, is not a name but a distinction. A Mary was a woman who was raised in a monastic environment while taking holy orders. Her surname comes from magdal-elder and means ‘watchtower of the flock,’ a position of distinction within a community.38 Thus Mary Magdala describes a holy woman who is a religious authority (tower) of the community. Following in her father’s footsteps, Mary too was inducted in the priesthood and risen from the dead, as confirmed in Mark 5:42 and in Voraigne’s Legenda Aurea, “And straightway the damsel arose, and walked; for she was of the age of twelve years.”39

During this period The Way was a fundamental component of the raising ceremonies of the Essene community of Qumran whose initiates were referred to as “those of The Way.” In ancient times Qumran was called Sekhakha. Since the area had previously been under Egyptian rule, it is possible the name is a variant on Saqqara, the Egyptian temple complex dedicated to Seker, falcon god of the Amdwat.

Lomas Rishi, one of the oldest rock-cut initiation chambers dedicated to Krishna. India.

The Essenes shared many traits with contemporary Gnostic sects such as the Nazoreans, and sufficient evidence shows both groups were one and the same, to the degree that the names were combined as Naassennes;40 another was the Mandeans—whose name originates from manda meaning ‘perception knowledge, gnosis’41—who to this day in southern Iraq still conduct initiation rituals leading to forms of ecstasy. Their texts state how the methods used to access the Otherworld were once those of Egypt.

The Essenes were said to be “faithful even unto death” rather than give up the secrets of The Way, as though these mystics held a special covenant with God that embodied the spiritual aspirations of all peoples. And they may well have, for the secret books they hid under Temple Mount were said to contain rituals and knowledge “revealed by God,” information offering nothing less than Paradise itself.