6

Secrets of the Beehive

A recurring characteristic of Celtic ritual chambers is the fitting of interior roofing stones to simulate a beehive, Newgrange being a particularly well-preserved example. As is the east-facing passage mound of Kercado, one of the innumerable components that compose the ritual landscape of Carnac, and at circa 5000 BC, one of the oldest known passage mounds in Europe. Its inner stones are etched with the familiar checkerboard pattern symbolizing the interplay between dark and light that characterizes the causal forces in this world and the next. This universal law was originally encapsulated in the ancient Chinese board game of Siang k’i, which itself has strong associations with divination and astrology. On its slow migration westward the game was resurrected by Islamic intellectuals with the name it is known by today—chess.

To all intents and purposes the game is analogous to a Mysteries play. The movement of each piece represents the eternal struggle between the antagonistic forces of ignorance and knowledge. Some of its adherents even played the game blindfolded to demonstrate the extraordinary capabilities of a fully engaged soul. The checkerboard was adopted by the Knights Templar as the representative difference between the unconscious and the risen, and subsequently by their progeny the Freemasons, who to this day incorporate the concept in their 3rd-degree initiation ritual: the removal of the blindfold from the candidate after he or she is raised from a figurative grave and declared ‘risen.’

Traditionally, the trajectory of the soul into the Otherworld is westward along the sun’s bridle path of descent into the darkness of the primordial ocean. Looking westward out to sea from the coast of Ireland, the last bastion of solid form before the mutable horizon is Skellig Michael, a peak of natural basalt that thrusts skyward out of the Atlantic like a black pyramid.

A walk . . . no, a suicidal trek up its vertiginous path to the summit rewards the survivor with the magnificent sight of six clocháins—stone beehive chambers. Besieged by utter tranquility, this loneliest of human outposts is devoid of all material distraction as though deliberately sculpted for pilgrims wishing to contemplate the world beyond the physical. In the sixth century the site functioned as a hive for monks escaping the temporal world to engage in meditation and solitary spiritual concerns. Only the distant Irish shore beckoned their return upon resurrection from their inner expeditions.

Skellig Michael. On a calm day.

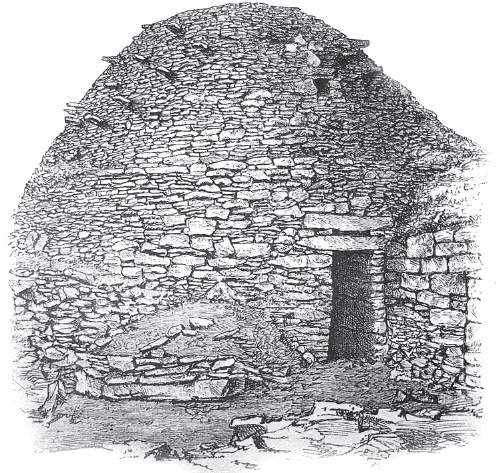

Beehive chamber, Skellig Michael.

These stone cocoons would not have seemed strange to the Yaqui and Seri tribes who lived near the border of Sinaloa, Mexico. In 1947 a cave was discovered in the nearby mountains at an altitude of 7,000 feet, filled with huts shaped like beehives. The natives had almost vanished by that time, as had the people who once built this secluded paradise. But the beehive huts contained the mummies of giants up to nine feet in height, wrapped in saffron-colored robes, upon which were painted blue pyramid emblems with dots. The locals claimed they belonged to a race that originated from a land submerged long ago.1

During a trip to South America I was surprised to find the beehive chamber was also used in this part of the world, and quite possibly for identical rituals. In Peru, whenever one is offered the explanation of a sacred site as pre-Inca, it is archaeological speak for “we have no bloody idea who built it,” which essentially applies to most Andean prehistory. Such is the case with the tall, pre-Inca towers known as chullpas that grace the flat buttes at Cutimbo and Silustani.

The Inca were not a particularly dab hand at large masonry, particularly the megalithic sort, as proved when 20,000 men attempted to haul a gargantuan stone at the temple of Ollayantambo, only for 3,000 of them to be crushed to death when the ropes failed.

The chullpas are also built with massive curved stones, fitted together tongue-and-groove style, and so tightly arranged that an alpaca hair cannot be inserted between them. No mortar was ever used. Later towers are fitted to a similar high standard, tapered, and finished in more linear fashion as though by a cosmic draftsman.

Chullpa at Cutimbo, Peru.

The structures are referred to as uta amaya (houses of the soul). Notice of the soul and not for the soul, a seemingly innocuous difference yet a major one, because it indicates their original purpose was not for burial—the orthodox excuse—but as places of facilitation. Even the sixteenth-century chronicler Pedro Cieza de Leon, who was himself half Inca and half Spanish, suspected that the enigmatic towers may have been reused for burial during Incan times but originally served a ritual purpose.

He may have been right. One of the towers had its face blown out, thankfully revealing how the core masonry was designed in the shape of a beehive. There is only one way in, through a tiny rectangular hole, forcing even the smallest of people to scramble on all fours, as though made to enter and exit the structure in a state of humility—one of the prerequisites for ritual initiation. And just to make the case, every entrance on every chullpa is oriented precisely east. If you happen to be at the main chullpa in Cutimbo around midday, with the sun at its zenith, something very wondrous occurs: the light cast upon the stones reveals relief carvings above the doorway of what appear to be a male and a female figure, the symbolic coupling of the initiate with the bride. Possibly. The figures are weathered. However, there also come into view the reliefs of two large dogs, which at first glance seems an unusual choice of creature to etch at the entrance to a ritual chamber—unless you understand the Aymara religious system, which taught that a soul experiencing resurrection undergoes an ordeal while finding its way to the Otherworld. The Andean account of this afterlife journey uses the symbol of a bridge across a raging river, and as the soul crosses the river it is assisted by black dogs capable of seeing in the dark—much like the hounds of Hades of the Greeks, the Cŵn Annwn escort dogs of souls in the Welsh Otherworld, and Anubis and Upauat of the Egyptians.

Canine and bride reliefs.

Such beehive chambers exemplify a long tradition of association with the bee. Since the bee and the honeycomb effortlessly characterize the manifestation of divine harmony in nature, bees were considered a link between life and afterlife. Nature gods such as Vishnu, Pan, and Aphrodite are depicted as honeybees on a flower, while in the Egyptian creation myth, the sun god Ra cries tears of honey that transform into honeybees the moment they touch the earth. Priestesses honoring the cults of fertility such as those of Ceres and Demeter were nicknamed bees, as were the women who assisted candidates undergoing initiation in secret chambers.

The honeycomb was similarly linked with personal insight and divine wisdom, a concept immortalized in the Bible: “Jonathan . . . put forth the end of the rod that was in his hand, and dipped it in a honeycomb, and put his hand to his mouth; and his eyes were enlightened.”2 The theme was picked up by those keen observers of the Mysteries secrets, the ancient Greeks, with Sophocles describing how souls are carried through into the Otherworld as a swarm of bees: “Up [from the Otherworld] comes the swarm of the souls, loudly humming.”

Where passage mounds feature flat-roofed chambers, one is shaped as a beehive, indicating the design didn’t just serve a structural purpose. Achnacree, Scotland.

Beehive chamber and passage. Newgrange, Ireland.

In Ireland, bees were religiously revered because they produce honey, the principal ingredient of mead, the drink of immortality that flows in the Otherworld (hopefully in everlasting quantities). The fact notwithstanding that bees hibernate for three months before reemerging, such attributes explain why the industrious little insects are depicted on ancient tombs as symbols of resurrection and the Otherworld. On occasion, honeycombs also appear inside subterranean chambers, and in doing so reveal the true purpose behind such curious compartments.

The island of Malta takes its name from the Phoenician maleth, meaning ‘haven,’ and later melita, or honey. Obviously this does not immediately qualify the island as a haven of the Otherworld, after all, Malta is known for an endemic species of bee that thrives on this tiny jewel in the Mediterranean and produces a fair supply of the golden sticky stuff. However, Malta’s unusual temples—forty of them on a speck of limestone no more than sixteen miles by eight—do.

Malta’s cyclopean temple architecture appeared out of nowhere, completely developed without precedent by 3200 BC, and on too small a footprint to have sustained the earliest architectural civilization. In short, its civilization territory is missing. With trefoil designs giving them the appearance of wombs, and originally capped with beehive domes, nothing looks like them. Such three-chamber designs are proven to be astronomically significant, yet like most temples, they served multifunctional purposes. From the initiatic point of view, each chamber was used to teach an understanding relating to creation, body, and spirit, and their relative correspondence to Under-, Middle-, and Otherworlds. The chambers were either adjoined or ascended in floors, and as the neophyte moved from vaulted room to vaulted room, to them would be revealed secrets of self-mastery en route to a revelation of inner perception.

When the Maltese temples were originally excavated, they were found covered in a three-foot-deep layer of sterile soil, as though the entire island was once subjected to a titanic tsunami that deposited thousands of people and animals unceremoniously into every available sinkhole, bringing to an end all human and temple activity. A new culture emerged hundreds of years later and rebuilt on top.

In 15,000 BC, however, it was a most desirable place to live, connected as it was by a land bridge to Sicily, the warmest part of a continent mostly covered by ice sheets three miles thick. That all changed three thousand years later. The land bridge collapsed, sea levels rose sixty feet, Malta suffered a violent loss of land, and all that remains are the four chunks of archipelago we see today.

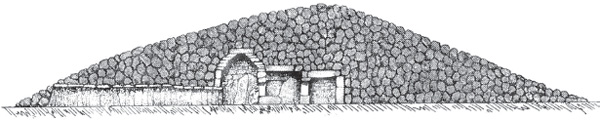

Malta’s oldest temple rests on the bedrock of its smaller adjacent island, Gozo. Folklore maintains it was built by a giantess by the name of Sansuna whose ability to carry large stones was attributed to her vegetarian diet, which, although admirable, may be an ancient echo of the earliest cult of Demeter, the goddess of grain, and its connection with the hallucinogenic fungus ergot. Called Ggantija (tower of the giants), it is one of the oldest freestanding structures in the world, erected a thousand years before the last phase of the Great Pyramid in Giza and Sumeria’s mud-brick temples, apparently by people with no accumulated knowledge of building sophisticated structures, and on an archipelago said to have been largely uninhabited.

Womblike design of the double temple of Ggantija, originally covered with a beehive roof.

Ggantija is officially dated to circa 3200 BC so as to shoehorn it within an academically acceptable time frame. And this is where the problems begin. The oldest, and biggest, stones—some weighing sixty tons—show signs of extreme water erosion on an island that last experienced a substantially wetter climate closer to 8000 BC, with the Sahara to the south sharing the same climatic footprint.

Then there is the issue of archaeological evidence of local human habitation and cave art dating to the Paleolithic, along with remains of animals that were last seen at the end of the ice age, stranded in Malta following the collapse of the land bridge.

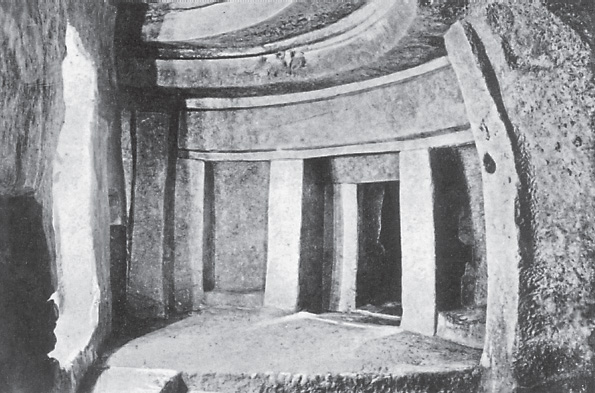

Ggantija’s other anomaly is that it is a double temple; it is paired with an adjacent subterranean structure. And here begins the association with the Otherworld and the ritual of living resurrection. Of Malta’s forty known temples, barely twenty-three survive, most of them lying in desperate states of repair. Many feature satellite underground chambers, also in various stages of abandonment. But in 1902, workers digging a cistern accidentally broke through the ceiling of a complex and well-preserved subterranean ritual temple that became known as the Hypogeum of Hal Saflieni, which may have served as the underground component of the nearby temple of Tarxien. The limestone bedrock hasn’t just been cut into spacious passages, but also hollowed into thirty-three contiguous halls and chambers on three floors with a footprint of a quarter of a square mile.

Inside the Hypogeum of Hal Saflieni.

Accumulated layers of soil yielded pottery dating to 4000 BC and human remains to 2200 BC. But evidence suggests the Hypogeum is neither that young nor was it ever intended as a burial site, at least not deliberately, because over seven thousand human remains were found violently mixed with those of animals and sundry debris as though dumped into the caverns by a sudden, catastrophic event—such as the floods that overwhelmed the island around 2200 BC. Hundreds of skeletons had elongated skulls identical to those of Egyptian pharaohs, and of the giants buried in long barrows throughout the British Isles. Figurines of the Earth Mother, in a style contemporary with European art between 4000 and 7000 BC, were also exhumed, in addition to Paleolithic cave art consistent with the same between 8000 and 30,000 BC; one image is an outline of a large human hand with six fingers.

Anyone who visits the Hypogeum cannot but be moved by the way the acoustical resonance lulls the senses into a receptive state. The hollowing of an estimated 2,000 tons of stone into carefully designed chambers allows low sounds made in certain places to be clearly audible throughout all three levels. It is a sensory environment perfectly designed for immersion into a subtler level of reality. The big clue appears in the red ochre and black manganese paint still daubed on the ceiling of its most resonant room, the Oracle Chamber, in the shape of interlocking hexagons, making one feel as though inside a honeycomb. And since the style is consistent with that of Paleolithic art, it places this environment in a time frame beyond 8000 BC.

During a quiet moment on one of my tours, the official guide took me aside in one of the chambers to tell me that working at the Hypogeum was for her the manifestation of a childhood dream. Without realizing the kind of research I do she proceeded to share with me how, of the myriad of hollows, she is magnetically drawn to sit in this very spot to pray or meditate when the Hypogeum is empty. She describes a sensation of leaving the body and feeling very protected as though in the company of benevolent spirits.

Quite a remarkable statement from an official guide.

She was also unaware of recent research proving how the chambers have been specially designed to conduct and manipulate sound to induce specific sensory effects, a feature common to monumental structures from Turkey to Peru. The resonant frequency of the Hypogeum is 112 Hz, and the designers wanted it just so. At this frequency the pattern of activity over the prefrontal cortex of the brain abruptly shifts, resulting in a relative deactivation of the language center and a temporary shift from left- to right-sided dominance related to emotional processing and creativity. This shift does not occur with adjacent frequencies of 90 or 130 Hz, so by design, these chambers are deliberately switching on an area of the brain that biobehavioral scientists believe relates to altered states of consciousness.3

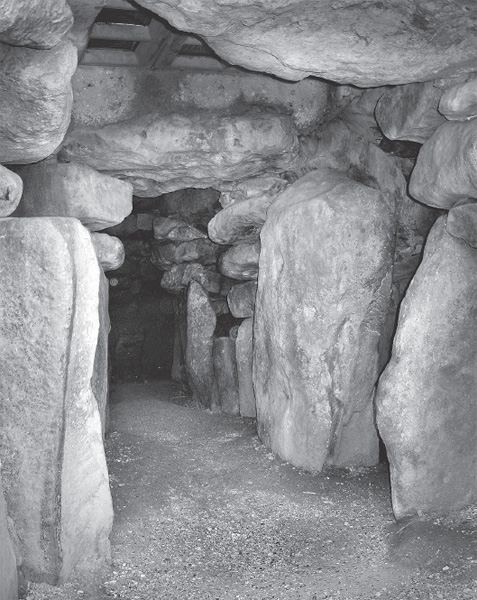

Giant’s passage grave with beehive chamber. West Kennett, England.

Malta’s Hypogeum is not alone in this respect. Experiments into the acoustic behavior inside very ancient sites, such as Ireland’s Newgrange and England’s Chun Quoit, Cairn Euny, and Wayland’s Smithy, found that the chambers, although designed to different configurations—oval, petal, cruciform, and beehive—all sustain a strong resonance at a frequency between 95 and 120 Hz. Internal and external petroglyphs even resemble the acoustical patterns generated by modern sound equipment.4

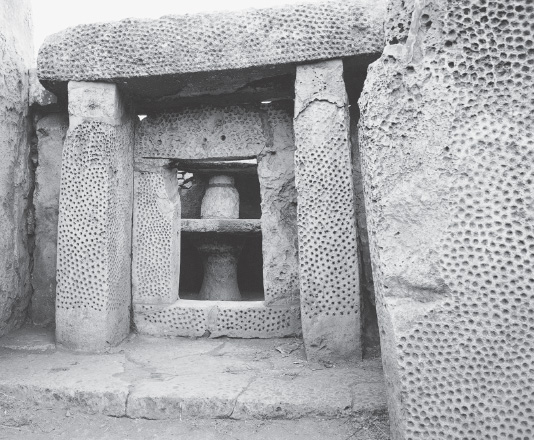

On the southwest cliffs of Malta, the surface temples of Mnajdra and Hagiar Qim may have played similar parts in the Mysteries play of living resurrection. The architects left no written record of what took place here—not uncommon given the secrecy with which they protected valuable information—but a glance at the unique way the stones’ faces have been deliberately carved gives the game away: they are covered in small holes that from a short distance make the temples resemble massive honeycombs.

There exists a linguistic piece of evidence that further links ancient Melita to the initiation practices of the Mediterranean, and it is found in a nymph called Melissa.

Honeycomb pattern. Temple of Mnajdra, Malta.

A nymph is the personification of the female creative force of nature. Its Greek root nymphe also means ‘bride’ and ‘veiled.’ She’s the kind of young maiden one marries, even though she is reachable only in places far from human habitation and often by a person traveling alone—not unlike the description of the initiate undertaking a journey to a distant realm.

The Greek historian Porphyry describes how in the temples presided by Artemis, Demeter, or Cybele, the priestesses-in-attendance were called Melissae—the bees—and that this insect came to be associated with the concept of periodic regeneration by the manner in which the Melissae inherited their title from Greek mythology.

Melissa was one of a group of bee nymphs whose duty was to teach civilizing behaviors and bring men out of their state of ignorance. The antiquarian Mnaseas’s account of Melissa gives a good picture of her function in this respect. According to folklore, Melissa was the first to find the honeycomb, taste it, and then mix it with water for a beverage. She taught others to do this, and thus the bee was named for her. Upon discovering the virtuous quality of this beverage, when she became attendant to the infant Zeus, she fed the god honey instead of milk so that his eyes could be opened.5

Porphyry wrote extensively of the priestesses of Demeter. When Melissa’s neighbors tried to make her reveal the secrets of her initiation she remained silent, never letting a word pass from her lips. In anger, the women tore Melissa to pieces, causing bees to be born from her dead body.

In the sixth century BC the Orphic Mysteries pervaded Greece and the islands of the Mediterranean. The Orphics affirmed the divine origin of the soul, knowledge of which was achieved through initiation into the Mysteries and its process of transmigration. Initiates purified themselves and adopted ascetic practices for the purpose of cultivating the perfected human within. In one segment of Orphic poetry, Melitta is spoken of as a hive named Seira, the hive of Venus. “Let us celebrate the hive of Venus, who rose from the sea: that hive of many names: the mighty fountain from whence all kings are descended; from whence all the winged and immortal Loves were again produced.”6

Seira was synonymous with the goddess Demeter, whose temples were referred to as “houses of Melitta”—just as in earlier times Mylitta was the Venus of the Babylonians.

Interestingly, in Gaelic Ireland, Melissa appears as Maoilíosa, and means ‘servant of Jesus.’

That Malta once served as a place of pilgrimage for seekers of the Mysteries preparing for the ultimate ride of their lives in the Otherworld is hidden in plain view in a classic of Greek literature, The Odyssey.

In Homer’s time poets were called Divines, and poetry, the language of the gods. Although his epic is set in the mythical island of Ogygia, Malta may have served as his inspiration. The island is the residence of the nymph Calypso, whose siren call lures Odysseus to be shipwrecked, whereupon she keeps him for seven years, hoping to make him her immortal husband. But Odysseus has other plans. He cannot bear to be parted from his wife, Penelope, so it falls upon Hermes, the god of wisdom, to tell Calypso to set him free, for it was not Odysseus’s destiny to live with her forever in an altered reality, but as a mortal in an earthly environment. So Calypso sends him on his way in a boat, with bread and wine.

Like most myths the story is an allegory, a container for a spiritual truth. For starters, the name of the island is deliberate. The Greek adjective ogugios means ‘primeval,’ so the land to where the hero is lured is a place apart from his own time and space—much like the location one travels to in an altered state.

Then there’s the nymph Calypso—also a purposely invented name meaning ‘concealment of subtle knowledge’—who possesses supernatural powers and lives in a cave surrounded by cypresses and black poplars, all classic symbols of the Otherworld. Like the Celtic Brigit, Calypso is the bride who calls to Odysseus and steers him with her voice through the nightscape of the Otherworld so that the hero can immerse himself in the knowledge of the gods, and for which he is rightly offered eternal life. Odysseus is content enough at first but eventually realizes he has to apply what he has learned in this parallel universe for the knowledge to be of use in his mortal life, and thus he returns to the waking world.

Trident, symbol of transformation. Navajo sacred site, Monument Valley.

Like the classic journey of the initiate pursuing the Mysteries, all that is tangible in Odysseus’s life is challenged—his absence from home, his ego, his desire—because in order to become an improved man he needs to follow the call of sacred knowledge to a place separate from the rest of the world, an island apart in the west. Homer’s point is that to become more aware of life, one must take a break from routine and connect with the laws of the universe, via initiation if necessary. The story even opens with Poseidon, husband of Demeter, whose trident is the very symbol of transformation, just like Siva’s—just as the symbol of the trident carved on the stones of sacred places announces them as locations set aside for shamanic migration and spiritual transformation.

Calypso mourning Odysseus’s departure from Ogygia.

It seems then that Homer’s epic is describing the initiate’s immersion into the Mysteries, whereby he undertakes a journey into the Otherworld and returns resurrected. Given how Homer the Ionian was himself initiated in the sanctuary of Tyre, he was merely retelling his own experience in a manner that did not betray the secrets of the Mysteries, precisely as Plato remarked, “Homer’s Hymn to Demeter, Pindar, and Sophocles already praise the bliss of initiates in the Otherworld, and pity those who die without having ever been initiated.”7