13

How to Travel to the Otherworld and Back. Or, the Pyramid Texts

Nine pyramids transfix the sky at Saqqara, a sprawling ceremonial temple complex named for Seker, the falcon god of rebirth.

The name arises from sy-k-ri (hurry to me),1 the cry made by Isis to Osiris as he wanders through the darkness toward the Otherworld, seeking to unite with his bride and become one again—an action uncannily similar to the Celtic goddess Brigit’s keening cry.

These factors alone identify Saqqara as a place where one comes to experience resurrection, and indeed it is in Saqqara where one finds the earliest surviving works of sacred literature offering a unique window into a ritual experience connecting a living person with the Otherworld.

The Pyramid Texts contain the most vivid and detailed instructions of the Amdwat, its halls and partitions, how to get there, how to overcome negative forces at the onset, what to expect to encounter at each hour, and the correct use of spells and incantations essential for the soul to maintain focus throughout the entire pilgrimage. They are a written prototype of the Mysteries teachings, and quite possibly the first time such a ritual was transmitted visually rather than orally. Their influence resonates throughout all Mysteries schools. But above all, the Pyramid Texts clearly imply they were intended as a ritual where the initiate was expected to return to the living body.

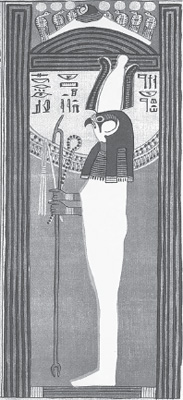

Seker. As protector of special chambers, part of his duty was to oversee the satisfactory transit into the Otherworld.

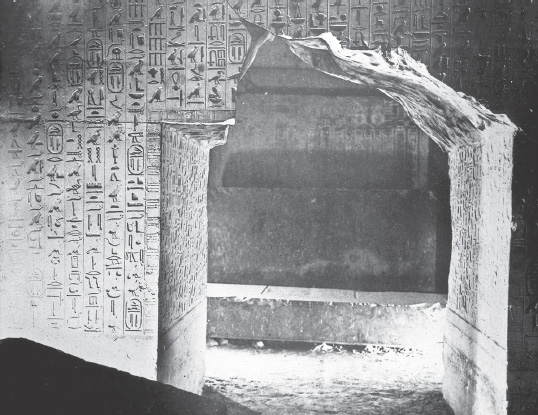

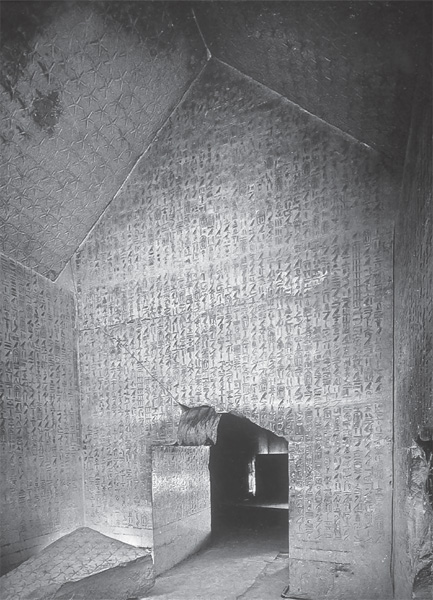

From floor to ceiling the texts cover the innermost subterranean chambers of the circa 2350 BC pyramid of Unas, raising the odds of this being the earliest version, and quite likely the one copied onto the walls of Thutmosis III’s own chamber almost a thousand years later. And like Thutmosis’s, this necropolis contains a sarcophagus but no evidence that Unas was ever buried here.

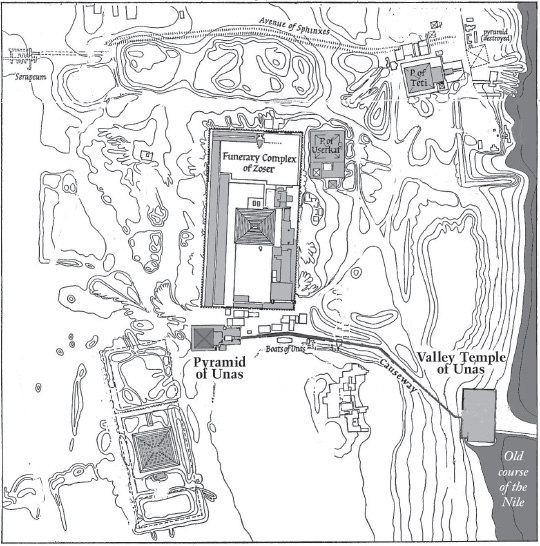

The pyramid of Unas was originally accessed by boat. The candidate was ferried from the east bank of the Nile and disembarked in the west into a small valley temple, then proceeded down a long, covered causeway leading into the subterranean temple, all of which was encompassed within a boundary wall containing the pyramid proper. Thus from the moment the candidates set foot on dry land, they were sealed off from the sunlight of the outer world to focus solely on their westward peregrination, following the path of the setting sun into the Otherworld.

Part of the Saqqara complex with the pyramid of Unas and its valley temple.

The odd thing when entering this pyramid today is that the first texts one encounters must be read from right to left, demonstrating that what is today taken to be the entrance into the main chamber is in fact the exit. Originally, the initiate would have entered below ground, resided in the womb, and reappeared resurrected at the summit of a man-made hill.

Because everything in the world of temple design was done according to the Law of Correspondence, even Unas’s massive black granite sarcophagus lies purposefully in the western section of the complex. Granite was the material of choice for sarcophagi in pyramids for a number or reasons. It’s an igneous rock emanating from deep within the Earth in a molten state, so it effortlessly mimics the soul’s immersion in the void, changing from a liquid state to solid form as it reenters the physical body following a transfiguration. It’s not by accident that the Egyptian word for granite, match, has its phonetic derivative in mat (to imagine, discover, conceive).2 In the case of Unas’s sarcophagus, the choice of black carries a further significance in that it was the color associated with the darkness of the primeval void where all knowledge resides, and through contact with this knowledge one comes to be spiritually resurrected.3 This gnostic concept is the reasoning behind statues of a Black Virgin discovered in grottoes throughout Europe.

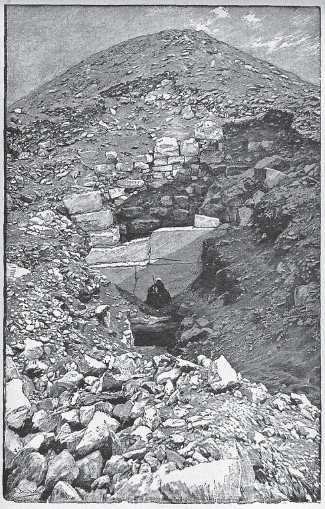

The Pyramid of Unas in the nineteenth century, Saqqara.

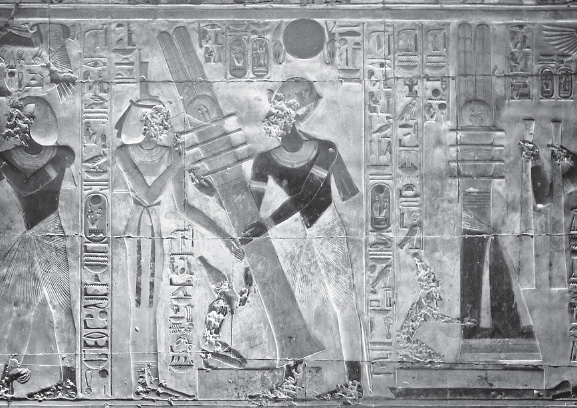

Far from being mere funerary beliefs, the Pyramid Texts encircling the sarcophagus represent a series of mystical experiences by the pharaoh—the mediator between material and ethereal worlds—akin to those described in shamanism, such as the ascent of the soul, encounters with gods, and the spiritual rebirth of the individual. The unusual theme that defines the Pyramid Texts as an instruction meant for a living person undergoing a figurative rather than a literal death is neatly encompassed in Utterance 213, the text closest to the sarcophagus: “O Unas, you have not departed dead, you have departed alive to sit upon the throne of Osiris, your aba scepter in your hand that you may give orders to the living, your lotus-bud scepter in your hand that you may give orders to those whose seats are hidden.” The message is very clear: the pharaoh has ascended into the Amdwat very much alive, and by following in the footsteps of Osiris he is now capable of communicating with the living and the discarnate alike. Like Jacob in his shamanic dream, the pharaoh is assisted in his upward journey by means of a ladder, in his case the Djed pillar, symbol of the very backbone of the universe.

Isis, Pharaoh, and Djed pillar.

A second clue that the Pyramid Texts were used specifically as a tool for the living lies in the pharaoh adopting the form of Horus. He repeatedly describes himself as “Horus, my father’s heir. I am one who went and came back,” and it is as Horus that he “rests in life in the West [the Amdwat] . . . and shines anew in the East.”4 This is a radical departure from the standard funerary utterance accompanying a dead pharaoh, who typically departs for the Otherworld as Osiris and stays there. It is his successor who adopts the form of the risen Horus, the son of Osiris who, in human form, represents the human spirit reborn.5

To emphasize the point, in the south wall of the sarcophagus chamber there is a description of a mystical experience in which the spirit of Unas, while imitating the path taken by the god of resurrection, himself undergoes a spiritual purification and rebirth to the repeated chorus of “Unas is not dead, Unas is not dead, Unas is not dead,” proceeded by the return of his spirit back into his living body.6 No other utterance from the Pyramid Texts so encapsulates the central theme common to all Mysteries traditions: that the soul is capable of temporarily disengaging from the living, physical body, journeying independently into the spirit world, and returning. It forms the central tenet of gnosticism. It is an experience designed for the living, and not to be left undiscovered until the moment one exhales his last breath on Earth.

Unas’s empty sarcophagus surrounded by the Pyramid Texts.

Unas’s chamber covered with the Pyramid Texts.

The point of the Pyramid Texts was for the soul of the living to be exposed to the Otherworld, to be met by Isis in her celestial role as Sophis—the representation of wisdom and the divine feminine—and return to the body with knowledge of celestial mechanics, apply them on a practical level, and allow the divine to flow through the conscious self while performing earthly duties.

Pharaohs who received initiation are identified by the effigies of the serpent and vulture placed above the brow, the seat of the third eye. The raised serpent’s position near the pineal gland represents the spiritualized pharaoh, one who has learned the secrets of inner journeying. It also demonstrates he has learned to harness the Earth’s telluric forces (represented by the snake), through which he is capable of rising above the urges of the flesh (represented by the vulture)—the transcended aspect of the material-seeking human, the physical urge held in check and spiritualized. In many ways it is a similar concept to the red ochre circle practicing Hindus paint on their brows.

The uraeus on Pharaoh’s brow.

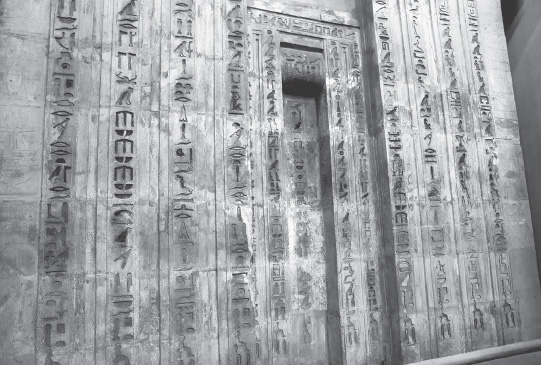

Ka door.

At Saqqara there is another recurring theme associated with the secret Mysteries, that of members of the pharaoh Teti I’s household being favored to join such a privileged inner circle. There exists an inscription on a ka door (a false door through which the soul flows) describing the surprise by one such individual upon being admitted to “master secret things of the king.” Teti built his pyramid beside that of Unas, and it contains part of the latter’s Pyramid Texts. The humbled servant continues, “Today in the presence of the son of Ra, Teti . . . more honoured by the king than any servant, as master of secret things of every work which his majesty should be done. . . . When his majesty favoured me, his majesty caused that I enter the chamber of restricted access.”7

At the end of his ritual experience, this grateful individual proclaims joyfully, “I found The Way.”