14

Pharaoh Has Left the Building

When the stepped pyramid of Sekhemkhet was excavated, its entrance and internal rooms were still sealed. Inside the innermost chamber stood an alabaster sarcophagus of the most delicate workmanship. It too was found sealed, and when opened it was discovered to contain nothing but air. No burial. Only strands of blue water lily lay on top of the sarcophagus; the same situation occurred at the pyramid of Zawiyet el-Aryan.

Two Old Kingdom pyramids, unburglarized, complete with sealed sarcophagi but no body inside—clear evidence that not all funerary buildings were intended as final resting places but served some other, possibly symbolic or ritual purpose.

Sekhemkhet’s pyramid lies adjacent to that of Unas at Saqqara, and both fall under the gaze of the imposing stepped pyramid of Djoser, undoubtedly the best-preserved structure of all, whose extensive courtyard was once the scene of a five-day Sed festival, typically performed during the pharaoh’s thirteenth year of reign and immediately following the annual rites of Osiris. The festival provides another clue strengthening the theory that the Saqqara complex, together with its Pyramid Texts, was once intimately associated with the ritual of living resurrection.

Stepped pyramid of Djoser. Saqqara.

During the festival the pharaoh underwent a twofold rite of passage. In the first and public part, his kingship was renewed, offerings were made, gods were visited in their shrines, and purification rites were administered, followed by a coronation ritual whereupon the pharaoh ingested a specially prepared meal.

The second part is altogether different in character. It was conducted hidden from view and involved the administering of secret rites to ensure the pharaoh’s rebirth. He entered a special room carrying the standard of Wepwawet—the jackal god whose title, Opener of the Ways, is highly suggestive of his function. He was joined by a sem priest who conducted funerary rites. Two other priests also entered the chamber: one was the Opener of the Mouth, while the other carried a white vest to be worn by the pharaoh to symbolize the union of Horus and Osiris.1

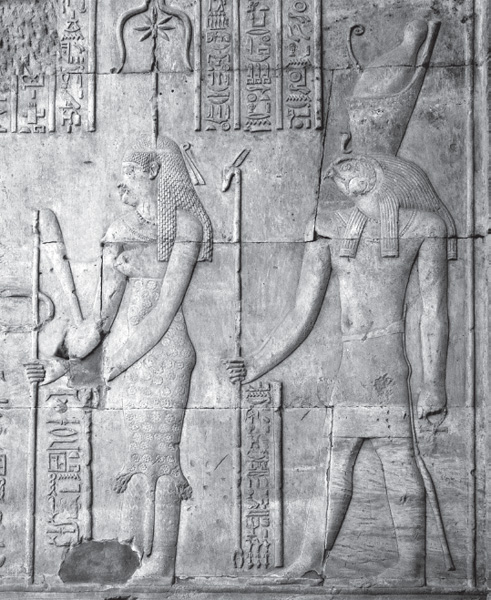

Seker holds the rod of the jackal; Seshat, goddess of sacred buildings, stands by.

All this preparation for the pharaoh’s embarkation into the afterlife is very odd considering he is in perfect health and at the height of his power.

Another rite follows, this time inside the ‘tomb,’ for which a special sarcophagus was commissioned.2 Painted reliefs in the chamber clearly show the pharaoh not lying down dead but upright and engaging with the gods in jovial form. It would seem that the pharaoh—who is described as “resting in the shrine”—is undergoing a preparation to immerse himself temporarily in the Otherworld to be spiritually renewed, for indeed he does return to his living body to resume his earthly duties until the day he physically dies.

An elaborately carved sarcophagus was likewise specially commissioned for the Sed festival of Mentuhotep IV, a pharaoh who continued living well beyond the event, making the sarcophagus redundant as a burial implement.

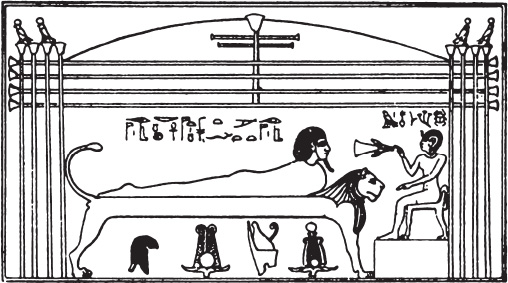

Reliefs of the Sed festival of Pharaoh Niuserre depict him drinking a libation and lying on a bed inside a bridal chamber. The same scene appears repeatedly in Dendera and Abydos—two temples intimately associated with the resurrection myth of Osiris—where the pharaoh is shown lying on a bed in a very animated state, his arm raised, sometimes lying on his stomach, but unmistakably alive.

Pharaoh lying on his stomach and given the hallucinogenic blue water lily.

The ritual white garment worn by the pharaoh in the Sed festival would survive two thousand years to reappear as the white tunic worn by the Essenes, and by those wishing to be indoctrinated into the secret Mysteries by Jesus. As with so many parables, the candidates around Jesus’s life tend to arrive in the night to be initiated—like the influential Pharisee, Nicodemus, who goes to see Jesus for rebirthing. Obviously people who are alive and well don’t go seeking rebirth, so the tales need to be interpreted with a metaphorical eye. For example, in the biblical parable of the king who invites guests to a wedding feast, of all the people gathered in the marriage chamber, one individual is not wearing his wedding garment—the white baptismal robe—and without it his presence in the chamber is deemed invalid.3

As we have already seen, the weight of evidence suggests Saqqara and a goodly number of its surrounding pyramids were originally designed with a sacred ritual in mind. For one thing, the layout of Sekhemkhet’s own pyramid complex is virtually identical to that of Djoser’s, and like Sekhemkhet, Djoser’s body was not buried in his own pyramid.

Likewise, ten pyramids from Seila to Dashur to Giza, all attributed to Sneferu, contained no sarcophagi or mummies, and in any case, why should a pharaoh possessing one body require ten separate funeral parlors?

A close look at the two pyramids at Dashur provides some answers. The Bent Pyramid’s adjacent valley temple contains frescoes depicting Sneferu performing his Sed festival.4 As does the nearby Red Pyramid; an inscription on the casing stones along the base commemorates the date of Sneferu’s thirteenth year in power, the mandatory time for a pharaoh to enact the Sed festival, while the stelae in the adjoining temple depict him wearing his ritual garb.5

If we take these observations and apply them to the three main pyramids farther north at Giza, similarities emerge. Each one features a lengthy causeway leading to a preparatory temple, and inner chambers containing an empty sarcophagus. In the preparatory temple of Khufu—Smenkhare’s son—there was found a small relief also depicting the pharaoh wearing clothing used specifically during the Sed festival.6

The fifth-century-BC Greek historian Herodotus remarked in his Histories that the pharaohs Cheops and Chephren (Khufu and Khafre in Egyptian) “were not buried in the pyramids that bear their names, but were rather buried elsewhere on the Giza plateau, in their vicinity.” So, could the Great Pyramid have been originally conceived with the ritual of living resurrection in mind?

Let’s begin with the basic assertion that this extraordinary marvel is referred to in a stela from the valley temple as the House of Osiris. One of the primary reasons why anyone would wish to imitate Osiris’s journey into the Amdwat is to attain wisdom. The exceptionally polished stone blocks that make up the base perimeter of the Great Pyramid add up to 1,461, which just happens to be the exact number of years in the Sothic Cycle—the complete cycle of Sirius, the star associated with wisdom.

Then there is the choice of building stone, which was far from arbitrary; according to the Law of Correspondence the stone reflected the purpose for which the temple was intended. The building comprises an outer casing of polished Tura limestone and an inner core made from colossal blocks of red granite, none of which are local building materials. Limestone, along with its cousin alabaster, was equated with ritual purity, while granite, a molten stone that hardens and is metamorphosed by pressure, was symbolic of transformation.

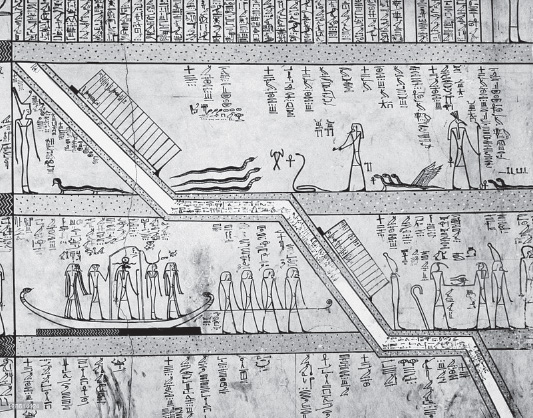

If one examines the drawings of the Amdwat painted inside the passage tomb of Thutmosis III and compares them to the interior of the Great Pyramid, there are striking similarities between the myriad of narrow corridors and rooms depicting the Amdwat and the pyramid’s claustrophobic chambers and passageways, as though the structure itself was designed as a three-dimensional simulation of the Otherworld. If we bear in mind that the purpose of journeying into the Amdwat was to, metaphorically speaking, polish a rough diamond, then some surprising observations come to light.

The Amdwat texts of Thutmosis III bear an uncanny resemblance to the Great Pyramid’s inner passages.

Herodotus and other early historians insisted that the Great Pyramid sat atop a far older chamber that was once accessible from the Nile. This would have been over seven thousand years ago when the climate of Egypt was far wetter and the Nile flowed closer to Giza than it does today. Access was via an underground tunnel that led to a mound surrounded by water, upon which sat a sarcophagus said to represent the original primordial mound of creation. An exit shaft rose above this sarcophagus and led to a rough stone chamber that today lies underneath the pyramid.7 Another account was given in the seventeenth century by the professor of astronomy at Oxford, John Greaves, who describes two elaborate cave-like architectural rooms attached to the north and west sides, thirty feet in depth and fourteen hundred feet in length, hewn out of the solid rock forming the pyramid’s foundation. The entrance is described as narrow, the construction of the rooms intricate, all immersed in darkness, but mostly inaccessible due to dirt. Greaves states that this complex had a connecting passage to the interior of the pyramid, which even then could not be found due to choking from centuries of accumulated debris.8

The rough stone chamber under the Great Pyramid can be visited today. Its central feature is indeed a deep vertical shaft, now filled with debris, so exit is made back along a narrow horizontal shaft that can only be negotiated by crawling on all fours. The shaft then inclines upward—exactly as shown on images of the Amdwat—and into the core of the Great Pyramid. Through a series of connecting passages one finally reaches the Grand Gallery—again ominously similar in design to the Amdwat images—and following a short climb another passage leads into the Queen’s Chamber, its angled ceiling bearing a remarkable resemblance to the central chamber below the pyramid of Unas.

Subterranean chamber beneath the Great Pyramid. The well described by Herodotus is in the foreground.

Returning to the Grand Gallery one continues to the top and toward a tiny antechamber, above which colossal granite plugs sit in the ceiling like stone guillotines. A short passage follows, requiring one to bend double before finally emerging into the so-called King’s Chamber. The room’s length-to-width reflects the mathematical proportion of the octave, its height the golden mean, nature’s mathematical progression; these measurements are mirrored in miniature in the sarcophagus.

The King’s Chamber is an image of the perfection of the universe, and by implication, whoever is immersed within becomes an image of that perfection. It makes for the ideal bridal chamber, and as you might already have guessed, no pharaoh was ever found here.

If the theory of the pyramid as an imitation of the soul’s ascent from the dark to the light is correct, then it is worth pointing out that the preceding description began in a rough-hewn chamber and culminated in its mirrored opposite, a lustrous box of stone—an accurate allegory of the initiate’s transmutation from rough form into polished mirror image of God.

Could the sarcophagus, then, represent the chest Osiris once entered before he was cut into pieces, reassembled, and resurrected as a god?

Writing about the places where the ancient art of resurrection was performed, the Reverend George Oliver, an eighteenth-century Freemason, describes how

[they] were contrived with much art and ingenuity, and the machinery with which they were fitted up was calculated to excite every passion and affection of the mind. . . . These places were indifferently a pyramid, a pagoda, or a labyrinth, furnished with vaulted rooms, extensive wings connected by open and spacious galleries, multitudes of secret dungeons, subterranean passages, and vistas, terminating in adyta [innermost sanctuaries], which were adorned with mysterious symbols carved on the walls and pillars, in every one of which was enfolded some philosophical or moral truth. Sometimes the place of initiation was constructed on a small island in the centre of a lake; a hollow cavern natural or artificial, with sounding domes, torturous passages, narrow orifices, and spacious sacelli; and of such magnitude as to contain a numerous assembly of persons. . . . And to inspire a still greater veneration, they were properly denominated Tombs, or places of sepulture.9

Oliver cites many ancient sources, his accounts approved for publication by the Freemasonic Society, a sect that does not publicly reveal such information lightly.

A comparison to the Egyptian pyramids and their ritual function was made by a traveler in 1638 when he visited the Indian pyramids—the pagodas of Deoghar (‘Home of the Gods’)—whose mention in the Puranas dates the original complex to the prehistoric era.10 These temples are of an arresting height, accessed by one small, solitary opening so that no light appears within except for what squeezes through the low entrance. In the center of the main pagoda is a dark chamber where religious rites were performed. The eyewitness describes the attendant chambers used by the priests and initiates as resembling excavated grottoes rather than recesses fit for practicing religious people. And just like their Egyptian counterparts, some chambers communicate with each other via narrow, uncomfortable passages.11

None of these places were ever known to have housed dead people. But living candidates, on the other hand, made good use of them, walked out into the light of dawn, risen from the dead, in far better shape than when they entered, precisely as promised on the temple walls: that sacred space exists to recreate the individual “as a god, as a bright star.”12

Part of the twenty-square-mile temple complex of Deoghar, one of the twelve most sacred abodes of the Eastern god of resurrection, Siva. Note the beehive domes.