15

Green Men, White Knights

As we approach the Christian era, contemporary commentators decry the degradation and loss of understanding of the Mysteries, due in part to their meaning becoming obfuscated through translation into other languages, not to mention the abuse at the hands of a centralized and corrupted priesthood. Too often the sacred teachings mutated into a control mechanism to inspire awe in lay people or to extract large sums of money for the privilege of delivering divine guidance, to the effect that by AD 364 the Roman emperor Valentinian published a law forbidding nocturnal esoteric activities, the aim of which was the prevention of indecencies taking place in establishments operating under the guise of Mysteries schools. The notable exception was Greece, where the correct performance of the sacred Mysteries was still understood to have a positive influence on the welfare of society.

As orthodox Christianity became even more orthodox, particularly under the rule of Theodosius, the ancient rites were obliterated, temples of initiation closed, and its practitioners regularly burned alive. Needless to say, secrets that had already been performed secretly were now even more secret. They went underground, literally and figuratively, enduring in parts of Greece until the eighth century, and in Wales and Scotland right up to the eleventh century before being resurrected by another secret sect, the inner brotherhood of the Knights Templar.

To illustrate the point, here is Article VII of the Templar’s Rule of the Elected Brothers, discovered quite by accident by the Inquisition as they ruffled through the pockets of arrested Templar Master Roncelyn de Fos:

Build in your houses meeting places that are large and hidden that can be accessed by underground tunnels so that the brothers can go to meetings without the risk of getting into trouble. . . . In the houses of unelected Brothers, it is prohibited to conduct certain materials pertaining to the philosophical sciences, or the transmutation of base metals into gold and silver. This shall only be undertaken in secret and hidden places.1

“Base metals” was a thinly veiled reference to uninitiated members, with “gold and silver” being the qualities of the risen hero (sun/gold) upon uniting with the divine virgin (moon/silver).

There exists an overwhelming body of evidence that the Templars followed rituals relating to raising the dead and in the tradition of the Essenes.2 How the Templars came upon this knowledge lies in their obsession to dig under Temple Mount, whereupon the knights discovered scrolls outlining the beliefs and practices of its former occupants, the Essenes. These had been buried shortly before those holy men in white were forced out of Jerusalem by an invading Roman army.3

The similarities between both brotherhoods are remarkable: both favored a monastic existence, wore white habits, disposed of their wealth one year after being ordained, believed in two levels of membership, and despite a broad outer group, only initiates were allowed into the inner sanctum of their temples.4 Both undertook vows of obedience and absolute secrecy absolutely, to the point where adepts took the teachings of The Way to the grave. And no wonder, both orders claimed to be in possession of very secret information offering nothing less than paradise itself.

As we saw earlier at Gisors, the Templars made use of restricted passageways and chambers in a style similar to Egyptian protocol. One of numerous Templar sites, the most famous of which still exists in Portugal, was in the town of Tomar.

Tomar seems like an invented name. It was originally spelled Thamara, the Arabic word for palm tree, except the local climate of the period was too cold to support such a species; the palm, on the other hand, is the symbol of the resurrected Osiris. In Portuguese, the word means ‘to drink,’ but since it is impossible to drink a town, obviously the term is a euphemism, for indeed when one partakes in the Mysteries one is said to “drink of the Knowledge,” one imbibes from the “cup of everlasting life.” To add to the mystery, Thamara was also the name given to the daughter of Jesus and Mary Magdala.5

It was in Tomar that the Templars built their mother church, and as was their custom, they dedicated it to Mary. During restoration work in the 1940s a secret tunnel was found leaving its crypt and taking a mile-long excursion under the nearby river bed, the town square, then veering uphill before emerging beside the foundations of their most enigmatic monument, the charola, which literally translates as ‘a salver.’

A salver is a ceremonial silver tray and the very object upon which rests the Grail, as told in the famous medieval story.6

The Grail myth is an allegorical description of the hero’s arduous journey of self-discovery. In the end he is wedded to the beautiful maiden Sophia—the Greek term for wisdom—whereupon his eyes are opened, he becomes enlightened, and is figuratively raised from the dead.

Ascribing such an unusual name to the charola of Tomar implies that the building is the focal point of a resurrection play, and a mysterious one at that. This polygonal edifice is listed as a church and yet never did it have an altar; even more curious, during sieges the people of Tomar were never permitted inside the charola, arguably the safest, most secure building inside the citadel. And had they been allowed, getting inside would have proved awkward, for this building had no door. The only way in was from underneath and through the floor.7

The Templars’ primary temple. Originally it had no altar and no door. Knights and initiates would enter from under the floor. Tomar, Portugal.

Inside the charola of Tomar. Beneath its floor lies a hidden ritual chamber.

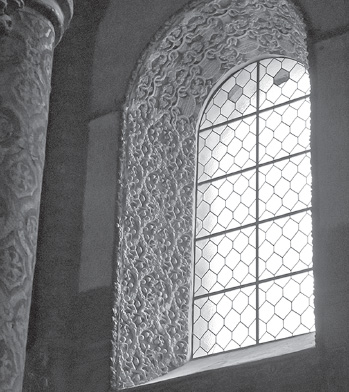

Beehive window.

It was at this moment that, standing inside the charola, I gazed up and noticed something unique to this Templar monument: the opaque white-and-gold window glass was shaped entirely of honeycombs. I was standing inside a beehive, the ancient talisman of resurrection and the Otherworld, later adopted by the Knights Templar and their benefactor, the Cistercian abbot Bernard de Clairvaux. If so, it was an indication that the Templar’s bridal chamber must surely lie beneath my feet. If only I could lift the flagstone floor, even if for just one second.

Perhaps I didn’t have to. An oral account by an elderly resident of Valado dos Frades recalls how, during restorations at the end of the nineteenth century,

it was the habit of one of the master masons to return home and register the alterations made inside the castle, because these would continue until much of what was old would be made unrecognizable or made to disappear. One of the things that riled him the most was the disfiguration of the beautiful and intriguing Arab pathway that the old monks of the Temple used in their ceremonies and led directly to the basement of the Temple church [the charola].8

Even in those days the brothers living in the adjacent convent used to share, from memory, stories with the masons of how Templar Master Gualdino Paes brought back from the Holy Land the plans of the Holy Sepulcher that were to be used for the construction of the charola. Master Gualdino also ordered a pathway leading to it to be constructed in the Arabic style, and both were used not just for religious ceremonies but also for the investiture of new knights. The monks referred to it as the “gate to the underworld,” its doorway resting on very old stonework upon whose uprights the Templars carved dragons, and on the supported lintel, a kind of winged serpent.9

During recent attempts to beautify the perimeter of the castle of Tomar—inside whose walls the charola stands—an area was cleared around the original gate to reveal a doorway into a cave. On its lintel is carved a winged serpent flanked by the heads of two dragons from whose mouths emanate a curl of breaths. A drawing made in 1918 shows the engravings still in their entirety, accompanied by a description of which parts of the Arab pathway were visible inside the subterranean passages and led to the bridal chamber beneath the charola.10

In 1988 an international group of experts attempted to locate said chamber, knowing there are entries, now sealed, and that the Templars built an access tunnel ninety feet below the ground. They liaised with the Institute of Geophysics whose ground-penetrating radar would be capable of detecting cavities up to 120 feet deep without leaving as much as a pinprick on the floor, yet despite this obviously unobtrusive and nondestructive scientific technique the Portuguese Ministry of Culture inexplicably prohibited all investigations.11

The bridal chamber may remain elusive but at least some of the knowledge that was imparted there is known, and it shows how the Templars exhumed an esoteric tradition and practiced it privately. To quote Article XVIII of the Rule of the Elected Brothers:

The neophyte will be taken to the archives where he will be taught the mysteries of the divine science, of God, of infant Jesus, of the true Bafomet [Source of Wisdom], of the New Babylon, of the nature of things, of eternal life as well as the secret science, the Great Philosophy, Abraxas [the Source of everything] and the talismans—all things that must be carefully hidden from ecclesiastics admitted to the Order.12

During initiation, candidates pushed away a proffered laurel wreath while uttering the phrase “My God is my victory,” the same idiom used in the Mithraic degree, Miles.13

CONNECTING TWO PALM TREES

There is another piece of evidence that shows the Templars were the latest in a long line of sects following a tradition of living resurrection, and it involves an ancient method of placing temples of veneration according to an underlying geodetic blueprint.

Immediately below the charola sits the charming town of Tomar—the palm tree—in whose main square stands a curious church the Templars dedicated to their other hero, John the Baptist. Inset into the front wall is a pyramidal bas-relief depicting what appear to be a large dog and a lion. An ancient Egyptian looking at this would make perfect sense of it, for the dog represents the Dog Star, Sirius, the embodiment of knowledge; the lion represents Regulus, the brightest star in Leo, long associated with the key to the Mysteries as well as a gateway to the records of all knowledge.

The story gets spicier inside the church, which is packed with pagan effigies, notably the dragon and the resurrecting god of nature, the Green Man. If you were to score an invisible line from the center of the charola to the relief, then thread the needle through two pillars inside the church marked by the effigies, the line extends two thousand miles to Jerusalem—specifically the Abbey de Notre Dame of Mount Sion, once home to another secretive order of monks named the Order of Sion, the force behind the founding of the Templars.14

Relief of Sirius and Regulus.

Green man and dragons. John the Baptist Church, Tomar.

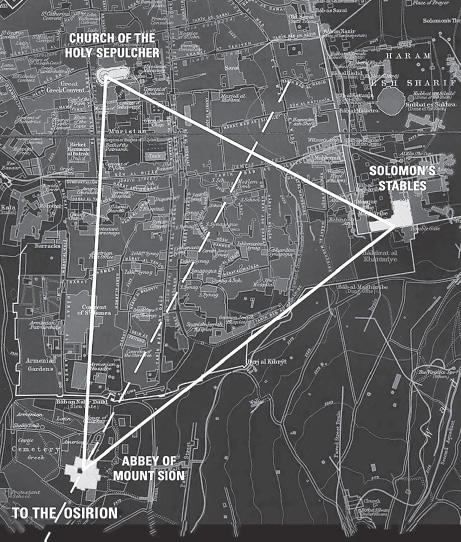

Still in Jerusalem, if we then plot the other two prime Templar locations—the church of the Holy Sepulcher and Solomon’s stables—the three sites form a perfect isosceles triangle, like the tip of pyramid. When this triangle is bisected, the imaginary line extends all the way to Egypt and the Osirion at Abydos, that other House of Osiris.

The tradition of using secret initiation chambers in which to practice the Mysteries or perform living resurrection was common throughout medieval Europe. They are found beneath countless pre-Christian churches and Gothic cathedrals, virtually all of them erected above preexisting ancient temples where identical rituals were earlier performed by Druids and other Gnostic sects. Some sites are well known: Chartres Cathedral, Mont St. Michel, and St. Germain des Prés, which itself is built over the original temple of Isis in Paris, from which the city gets its name. The Templars simply revived the corpse of a tradition long made dormant by ecclesiastic suppression, while their progeny, the Freemasons, followed suit, as the Freemason Reverend George Oliver once more elucidates:

The Templar’s Jerusalem triangle.

In some of the philosophical degrees, the place of meeting is figuratively termed a cavern, in imitation, probably, of the spurious Freemasonry, which was always held in the bowels of the earth; and the most stupendous specimens of the fact are visible to this day in the Indian, Persian, and Egyptian subterranean temples. In some places, entire mountains were excavated, and the cavern was constructed with cells, chambers, galleries, and streets, also supported by columns, and forming a subterranean labyrinth. Examples of this practice are found in the excavations underneath the great pyramid of Egypt; at Baia and Sena Julia in Italy; near Nauplia, in Greece; at Elephanta and Salsette, in India; at Ceylon; and in Malta is a cave, where we are told that “the rock is not only cut into spacious passages, but hollowed out into numerous contiguous halls and apartments.”15

A SCOTTISH PLAY IN BLACK AND WHITE.

On the origins of Freemasonry—first published in 1787—the Chevalier de Berage remarks, “Their Metropolitan Lodge is situated on the Mountain of Heredom where the first Lodge was held in Europe. . . . This mountain is situated between the West and North of Scotland at sixty miles from Edinburgh.”16

Sixty miles northwest of Edinburgh there is no Mount Heredom; instead there is Mount Schiehallion, the geodetic center of Scotland and its most sacred mountain, which we encountered earlier (p. 67). How did one become mistaken for the other?

In the fourteenth century a Templar Knight called Robert of Heredom was initiated in a cave on Mount Carmel. When the Order was rounded up by the French king, Robert moved to Scotland to be initiated again, this time inside the ceremonial cave on Schiehallion by a group called Sons of the Valley, who constituted a secret movement at the time. Joined by six more Brothers of the Cross, Robert of Heredom rode out to his new domicile at daybreak, as though signaling a rebirth, and subsequently resurrected the Order of the Temple in Scotland following its destruction in France.17

If this is indeed the spot where the first Metropolitan Lodge of Europe was held, it marks the establishment of Freemasonry in Scotland at around 1314—three centuries prior to the official date.18 It also means that Masonic ceremonies follow early Celtic Christian rituals performed since time immemorial on this mountain, as the Reverend Oliver writes in The History of Initiation:

The degree of H.R.D.M. [Heredem] . . . may not have been originally Masonic. It appears rather to have been connected with the ceremonies of the early Christians. These ceremonies are believed to have been introduced by the Culdees in the second or third centuries of the Christian era. Operative masonry existed in Britain at that era, as is evidenced by the building of a church at York, and a monastery at Iona; and it was in active operation before the twelfth century.19

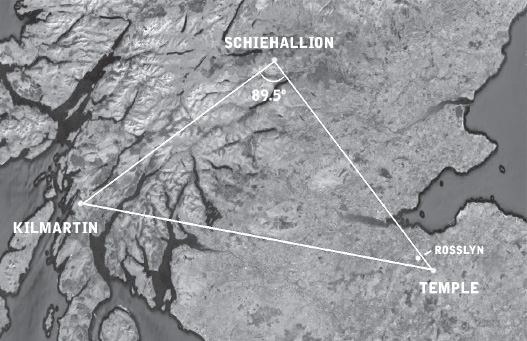

In the twelfth century the Templars set up their first preceptory in Scotland, in the hamlet of Baile nan Trodach (now called Temple), a few miles southeast of Edinburgh; their second main area of interest was Kilmartin, with its plethora of Neolithic sacred sites and ritual chambers. Together with the ritual cave on Schiehallion, the three locations form an equilateral triangle to an astonishing degree of accuracy, in effect creating a holy trinity of temples sharing similar purposes, and in accordance with the ancient world tradition of siting sacred places in perfect triangles.20

Geometric alignment of Templar sites in Scotland. The margin of error is just half a degree.

Three centuries later, an edifice rampant with pagan, esoteric, and Masonic symbolism was built just up the road from Temple—Rosslyn Chapel. In its time the building was given a stay of execution on the express orders of England’s pillager-in-chief, Oliver Cromwell, despite every other edifice of its kind in the area being razed to the ground. The fact that Cromwell was a Freemason may have played a small part in his decision.

One of the more perplexing stone carvings in Rosslyn Chapel appears on its exterior southwestern corner. It is of a man wearing a blindfold and a rope loosely draped around his neck, led by what appears to be a knight wearing a Templar tunic.21 A Freemason today would see in this a perfect depiction, even despite the weathered stone, of the ritual initiation of the candidate into the First Degree, one of Masonry’s most important ceremonies.

The First Degree.

The real enigma of Rosslyn Chapel is that it features virtually no Christian symbolism, and evidence suggests it was built in the image of the Temple of Solomon, from where Masonry also claims its roots.22 At the time of its construction in the fifth century there already existed an adjacent church dedicated to St. Matthew, aligned to face the solstice sunrise on December 21 and as such most likely built above a preexisting pagan temple, so why the need for an additional chapel where, aside from members of the St. Clair family, the congregation was regularly outnumbered by the chapel staff?23 Perhaps the enigmatic chapel was designed with another end in mind.

The visitor to Rosslyn will first be overwhelmed by the richness of detail. Three of its fourteen pillars in particular—the Journeyman, the Apprentice, and the Master Mason—represent the central tenet of the Solomonic principle: Wisdom + Establishment = Strength. A short flight of stairs to the right descends into a room in sharp contrast to the one above; for the crypt is mostly devoid of decoration save for some unusual mason’s marks and an eroded image of a half-finished arch. What is even curiouser is that this crypt never housed a body, and at one time its western wall opened into a labyrinth of tunnels, one leading to a metal shrine hidden beneath the center of the chapel above. This entrance was walled up at some point in the past; the metal shrine was only recently confirmed thanks to ground-penetrating radar but remains inaccessible as far as is publicly known,24 along with a second crypt that lies concealed below the first.

Is it possible these chambers were used as part of Masonic resurrection ceremonies? The Masonic tradition is, to all intents and purposes, a reenactment and continuation of the king-making ritual performed at Saqqara, even the use of the white apron in the Sed festival, right down to the ceiling in Masonic halls that, like Unas’s chamber, is adorned with stars. Its initiation ritual of the murdered apprentice is a reenactment of the life of Pharaoh Seqnenre Taa (also spelled Tao, The Way),25 while the ritual admittance into the Third Degree—where the candidate is raised from a figurative grave, his blindfold removed, and pronounced risen from the dead, as also enacted by female members of the Grand Lodge of Belgium—was similarly performed by the Essenes at Qumran.26

Apprentice Pillar. Rosslyn Chapel.

And like so many sacred places where living resurrection was practiced, Rosslyn’s crypt is entered from the west and exited toward the east.

This brings us to the chapel’s central feature, the Apprentice Pillar. Beautifully carved, possibly by a Portuguese mason (given how Portuguese masons were brought over to assist in the building work, and the pillar is in the unique Manueline style found in Tomar), it features four spiraling vegetations rising forth from the mouths of eight dragons around its base. These overt symbols of the regenerative power of nature are further enhanced by the inclusion around the chapel of dozens of representations of the Green Man, symbol of nature’s resurrection, culminating in the most extraordinary boss of a Green Man staring down from the chapel ceiling.

The building was founded in 1446 on the autumn equinox, no doubt accompanied by a ritual filled with symbolism, not least of all because, just before sunrise, the two brightest objects on the eastern horizon were Venus and the star long associated with the key to the Mysteries and gateway to the records of all knowledge, Regulus.27 Around the same period, 1,100 miles to the southwest, the same stellar alignment would have been used by the Templars as they began to build their church dedicated to John the Baptist in Tomar, the one featuring a host of Green Men and a bas-relief of Regulus the lion.

The Green Man, one of dozens in Rosslyn Chapel.

Divine Virgin and child, homage to Isis and Horus. Note the twin towers above her head, the castle of Mary and Martha, emblem of Mary Magdala and the vow of allegiance pledged by the Templars. Rosslyn.

In time Rosslyn’s east window would come to emphasize these prominent stellar objects and their values. Its geometry is based on the square and the circle, two forms representing the perfect mating of the masculine-material with the feminine-ethereal, the very process required of “the single man” that allows him passage to the final phase of living resurrection.

But there’s more. Just above this elegant work of glass and masonry is a small hole that, from a distance, appears circular but in truth is shaped in the form of a five-pointed star, emblem of the Divine Virgin, Isis. Made of red glass, it lights up with the rising of the sun at equinox, the moment light and dark are held in perfect equilibrium, like a checkerboard. The effect would have been even more pronounced when the original, smaller window was in place, which darkened the chapel considerably and made a person feel as though immersed in a sacred cave.

Like a continuation of the Mysteries: the checkerboard, symbol of the risen and the dead, outside John the Baptist Church, Tomar.

But it was outside where the stone masons, putting the final touches to the roof, left the most telling symbol of all: a stone beehive featuring a hole shaped like a five-petal rose, the very symbol of Venus.