CHAPTER THIRTEEN

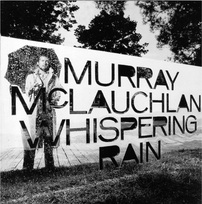

I was thrilled of course. We had our second worldwide hit single in a three-year period. Like Dan’s “Sometimes When We Touch,” Bruce’s single also did well in many countries around the world. What a remarkable period: between our management company and the record company we had a string of Canadian hits, including Murray’s biggest-selling Canadian album Whispering Rain, as well as the two bona fide international hits. Not bad for an air force brat who only fifteen years earlier was trying to find his way from Downsview to Yorkville.

As good fortune would have it, True North’s distribution agreement with CBS was coming to an end. That meant I could negotiate from a position of strength. The new agreement that CBS signed gave the label the ability to sign more acts, all with guaranteed marketing and promotion commitments. Arnold Gosewich was the president of CBS and he was anxious to keep us in the CBS family. Although Arnold is long gone from the record business we remain friends to this day. In essence, CBS would be advancing me the money needed to sign and record more artists. In return, CBS would have exclusive distribution rights for five to seven years – depending on the performance of the records – and then all of the distribution rights would return to my company. A sweet deal.

The time had come to sign another act to the label. As much as I loved working with singer-songwriters, and as good as that genre had been to me, deep down I missed the excitement that a great rock band can generate. A good song was still the most important thing on my mind, but I also wanted something that would be new and fresh and strikingly original. It didn’t take me long to find that something, although the truth is, I didn’t find it at all; it found me.

Carole Pope and Kevan Staples had been around Yorkville in the sixties and had been through various band incarnations, most notably O and then the Bullwhip Brothers. Yet somehow I just plain missed them during that period. It was as if we were living in parallel worlds even though we were right there on the same street. For me that whole period of the seventies was spent almost entirely in the world of “folk music,” or more specifically, of modern singer-songwriters. I had become something of an expert in that field. I knew every song and every artist, from the most successful to the completely obscure. The music was in my blood and certainly I had skin on the table; every move, and every song, mattered to me. There was never a moment, even when I was dreaming, that songs didn’t keep rolling around in my consciousness, 24-7.

So it was easy to understand how I might have missed the rising popularity of Carole and Kevan’s latest creation: Rough Trade. One day, in early 1980, I noticed that the band would be doing a show at the Danforth Music Hall, the former Roxy movie theatre in the east end, and decided to check them out. I was blown away. The show was sold out, a feat unto itself, and it struck me that Rough Trade might have been the best white R&B band that I’d seen since the early Rolling Stones. I was so caught up in the music that night that I almost missed the whole social movement that had helped to fill that theatre.

In the mid-to-late seventies, another cultural revolution was bubbling up from the streets, one that, like almost all post-war cultural shifts, involved music, fashion, theatre, art, and a loosening of sexual codes of behaviour. Here was Carole, completely out of the closet, singing some of the most provocative, politically potent songs I’d ever heard to a very engaged and fashionably hip audience. It was a world that I knew little about, but as the saying goes, I knew what I liked. I went backstage to say hello and before I could say anything, Carole asked me, why hadn’t I signed them yet? Well, throw me in the briar patch, I thought, or to put it another way, I invited Carole and Kevan to my office the next day, and we quickly worked out a contract that would include both records and music publishing. I really don’t know why somebody else hadn’t signed them before I did. Maybe the other labels were just plain scared of the sexual content of the songs, but the songwriting was just so good that I had no misgivings about giving them a deal.

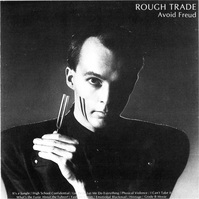

Carole and Kevan agreed that Gene Martynec would be the ideal producer for their debut True North album. And why not? Gene had a strong reputation for bringing out the best in singer-songwriters, and both Carole and Kevan considered themselves to be just that. With that decision behind us, we embarked on what would be a short but illustrious recording partnership. Soon we began work on their debut for us, the groundbreaking and breathtaking Avoid Freud.

Avoid Freud featured artwork from the multi-media art collective General Idea, whose three members, AA Bronson, Jorge Zontal, and Felix Partz, were all close friends of the band. GI came up with one of the finest and most innovative album covers True North ever put out.

Album jackets were always important to me. It costs as much to print a bad or boring cover as it does a good one, so why not make it as great and as interesting as possible? I also liked the idea of using Canadian artists and photographers wherever possible. Of course, this went back to my early days and that chance meeting with Bart Schoales, a talented artist himself, who over the years contributed so much to the look and feel of True North. Arnaud Maggs, the internationally acclaimed Toronto photographer, did several covers for us, as did noted fashion photographer George Whiteside and General Idea’s Jorge Zontal.

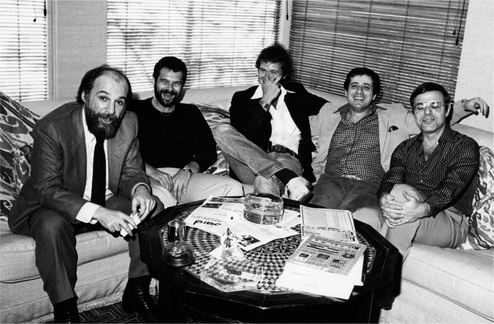

True North signs Rough Trade. From left to right:

Arnold Gosewich (Chairman, CBS Canada), Carole Pope, me, Kevan Staples, and Bernie Fiedler

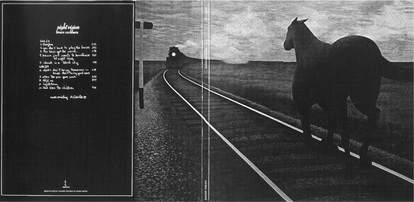

Many of Bruce’s album covers truly were works of art. Painter and illustrator San Murata, who works in a folk art style, created a wonderful cover for Salt, Sun and Time and I particularly liked Blair Drawson’s work on Joy Will Find a Way and Stealing Fire. We commissioned the great Aboriginal artist, Norval Morrisseau, who founded the Woodlands School of Canadian Art, to create the cover painting for Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws. We would later use Robert Davidson, another very fine Aboriginal artist, of the Haida nation, for the cover painting of Waiting for a Miracle. We had met Robert when Bruce was involved in the South Morseby benefit concerts in Vancouver supporting the campaign to stop the commercial logging that was devastating the Haida’s homeland in the Queen Charlotte Islands. Those shows raised over $50,000 for the Haida’s legal defence fund. And, of course, we had already used Alex Colville’s painting Horse and Train for Night Vision.

The album jacket for Murray’s Whispering Rain was a clever example of a great cover. It was done by the new-media artist Michael Hayden. He had at one time been a member of Intersystems, along with Moog synthesizer pioneer John Mills-Cockell. Michael had taken a look at the elements involved in doing a cover – photographs, typeface, layout, etc. – and condensed them all into one simple Polaroid picture. He die-cut both the album’s title and Murray’s name into a seven-by-four-foot piece of silver Mylar, then took the Mylar into a forest and stood Murray strategically in front of the cutout. Then he took Polaroid pictures until he had the one we all liked. No fuss, no muss, just a one-piece album front cover ready for printing.

I kept most of the original artwork for these covers and treasure them to this day. Later on, when compact disks replaced albums, I, along with many others, felt we had lost something special through the reduction of the package size. However, I continued to use Canadian painters where possible and had the good fortune to use a James Lahey painting for jazz guitarist’s Michael Occhipinti’s Creation Dream, an exquisite album of jazz interpretations of Bruce Cockburn’s songs. In hindsight I wish I had used even more Canadian artists over the years. It surprises me that more people in our business never picked up on this idea.

Alex Colville’s Horse and Train on Bruce Cockburn’s Night Vision album.

Murray McLauchlan’s Whispering Rain cover, created by Michael Hayden

Robert Davidson’s painting graces the cover of Bruce Cockburn’s Waiting for a Miracle

Norval Morrisseau’s painting for Bruce Cockburn’s Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws

The front and back of Rough Trade’s Avoid Freud by General Idea

As soon as General Idea finished the art we released Avoid Freud to the world. It turned out to be very successful in Canada, largely triggered by the raunchy “High School Confidential.” The first single we released was called “Fashion Victim,” and although it performed reasonably well, it didn’t exactly light up the charts. I had thought “High School” had the potential to become a hit but didn’t expect much airplay on top-forty radio. Not with lyrics that included the line, “She makes me cream my jeans when she comes my way.” Still, we decided to put it out with the hope that maybe some adventurous radio station would pick it up and play it. And we knew if that happened, it was bound to be an attention-getter.

At first, little happened. The album was getting some notice and was beginning to sell, but top-forty radio wasn’t on it at all. Yet it seemed obvious that once the commercial radio crowd heard this band, they were going to love them, and I hated the idea of a wasted opportunity.

About a month after we released the song I got a call from the music director of the mighty CHUM radio. They wondered if we would do an edit on the song, specifically to get rid of the word “cream.” I took the idea to Carole and Kevan and although they were somewhat reluctant they were willing to give it a shot. We examined several ways to do it but settled on a simple beep to drown out the word as the best answer. We sent our handiwork over to CHUM. The powers-that-be approved it, and the song was added to its playlist. As soon as CHUM’s listeners heard it, the phone lines lit up. For a while, it was the most requested song on the station. We rushed out copies of the edit to the other top-forty stations across the country and the record caught on from coast to coast. The bleep was like honey to a bear. Every time it was heard on radio, the curiosity of the listeners was heightened and out they went to buy the album that contained the unedited version. We sold well over 100,000 copies of that album in Canada alone. Avoid Freud was a great album but there can be no doubt that a simple little bleep helped push it over the top. As the record got bigger, radio actually started to play the unedited version and the world became a better place, at least for all of us at True North.

Carole Pope and Kevan Staples were true pioneers and visionaries. Carole, who was immensely creative, was also extraordinarily brave. She was open about her sexuality well before it became fashionable and safe to do so, and she did it gracefully and boldly. I’m extremely grateful to have had the opportunity to work with them.

But “High School Confidential” would not be Rough Trade’s biggest single. Their next album, the aptly titled For Those Who Think Young (a play on the name Carl Jung) contained a song called “All Touch” that immediately hit radio with a bang, and not only in Canada. I had made a deal in Australia for the whole True North label and the first releases were Bruce’s The Trouble With Normal, Murray’s Windows, and For Those Who Think Young. “All Touch” was released as a single and took off down under, landing in the top ten. At the same time, I had made a deal for Rough Trade in the U.S. with a label called Boardwalk, a subsidiary of Casablanca, owned by music business legend Neil Bogart, who had almost singlehandedly launched the disco craze in America with Donna Summer’s seventeen-minute single, “Love to Love You Baby.”

Another renowned music man, Irv Biegel, ran Boardwalk. He loved Rough Trade and was especially excited by the possibility of “All Touch” becoming a hit in America. We conceived a dynamic promotion campaign in the U.S. and the single started to take off. Irv was certain this was going to be at least a top-thirty Billboard single, and indeed it was beginning to move in that direction, but good fortune didn’t come our way this time around.

When Neil Bogart became sick, his company began to flounder and things came unglued. Getting records on commercial radio in America is an expensive proposition and always a tricky exercise. Money wasn’t the only necessary ingredient, although it seemed by far to be the most important. It also took a well-coordinated effort between all involved parties. With chaos reigning at the top of the company, things started to unravel. Just as the single hit number 58 on the Billboard Top 100 chart, officials at Boardwalk announced the company was going bankrupt. “All Touch” slowed down to a crawl. Sadly, a few months later Neil Bogart would die of cancer at the age of thirty-nine.

Jeff Franklin, Dan Hill’s one-time agent, represented the buyers of Boardwalk’s assets, so I flew down to New York to see if we could do something quickly to turn around the fortunes of the single and the album. Even though several weeks had passed since the single had peaked on the Billboard chart, I was still optimistic that we could turn it around. Why not, considering “All Touch” had been a top-ten hit in Australia and Canada and had been on the same trajectory in the U.S.? But Franklin was unmoved by my plea and the plight of the band; in fact, he was more than extremely unpleasant about the whole thing for reasons that I never understood. The meeting went nowhere, and although I did eventually get the rights back to the album, by the time that happened it was far too late to resuscitate the single. This was truly a tragedy. That song, at that moment, might well have broken Rough Trade in the States.

The next Rough Trade album was Shaking the Foundations, which we released in 1982. Arguably their best effort creatively, it didn’t have a track with the same kind of commercial appeal needed to break them in America. “Crimes of Passion” was the top single, but its content was just too edgy for an increasingly conservative radio landscape. With lyrics like the following, even I understood that we didn’t stand a chance at radio. But I couldn’t resist the challenge of putting this record out.

Her hand slipped down into the moistness of herself,

She pulled her knees up spread eagle on the bed.

Her chenille bathrobe, torn down the side,

He was a willing victim, he couldn’t resist her.

Shower still dripping, coffee table overturned,

The gun still smoking, scream caught in her throat.

Her lungs still burning, her tempo throbbing,

She reached for a crumpled pack and lit up a smoke.

There’s no limit to the depths you can sink to,

There’s no limit to the heights you can climb,

Crimes of passion, crimes of passion, crimes.

While there may have been no limit to the depths that Carole and Kevan’s characters might sink to, we did find the limit of what radio would play.

The video for “Crimes of Passion” was one of the most interesting made during those early days of the format. Whenever it was shown it would cause all kinds of talk. But we were never able to regain the momentum in America that had been lost with the untimely demise of Boardwalk. I can’t help but wonder what might have happened to Rough Trade had “All Touch” been able to continue its natural growth in the U.S., but what the music business teaches you is that nothing is guaranteed and absolutely nothing can be taken for granted.

Years later, in the late nineties, long after the band had split up, I was attending a music conference in the U.K., where I spoke on a panel with Geoff Travis, the founder of England’s seminal indie record label, Rough Trade Records. It was there that he told the assembled attendees and me that he had named his record store, and subsequently his label, after the band. Their legend lives on in many ways.

By 1981, finally, there truly was a Canadian music business. The Canadian-content regulations had done their job and I could see many positive spinoffs, not only for Canadian recording artists but also for many of the subsidiary interests tied to the business. Recording studios, equipment rentals, independent promotion companies, magazines, and many others directly benefited from the growing popularity of domestic artists. Our trade organization, CIRPA, was active in lobbying the federal government not just about regulations but also about funding. Although many of the leading artists of the time were signed to the independent labels who made up the vast majority of our membership, others were signed directly to the multinational labels whose executives, having seen that profits could be made, were beginning to take a very active role in signing and recording Canadian artists. Radio had been dragged unwillingly into the new world of Canadian-content regulations, but for the most part that fight was over. Yes, a few broadcasters still carried a grudge about being regulated, but by and large we were all working together to make things better. The one thing that CIRPA knew, though, was that its membership was chronically underfinanced, so we continually tried to induce the federal government to come up with a funding program to help our labels.

Independent labels, like True North, were entering an era of even greater competition now that our own distributors, the multinationals, were trying to sign the same acts as we were. Nothing was getting easier. The big companies at this time – CBS, RCA, EMI, Warner Brothers, PolyGram, and several others – not only had the advantage of large staffs and local offices across the country, but they also enjoyed a consistent revenue stream as hit after hit was delivered to them free from any real cost, since that had already been absorbed by their U.S. or U.K. owners. All they had to do was announce the release of a record that was already a hit in America (and perhaps in the U.K. as well) and Canadian radio programmers instantly put it on the air. The broadcasters even paid consultants whose main job was to read the foreign music trade magazines and tell them which songs were hits. When you consider that the album covers, posters, bios, and all the rest of the promotional material were supplied by their international parent companies, the Canadian-based multinationals really didn’t have to do too much except wait for the money to flow in.

With radio already aware of the U.S. hits, it left our small Canadian companies fighting a pretty steep uphill battle. The idea that a station would ever play more than the required 30 per cent Canadian content never seemed to occur to any of the major radio stations, and there were many instances of the stations getting away with playing less. Of course the multinationals didn’t mind this, since they owned the other 70 per cent. So it was left up to CIRPA and others to be on the front lines of monitoring this situation, and sometimes the front line is exactly what it felt like.

During this period, the federal and provincial governments had little interest in popular music. It always made me angry when I heard a politician or bureaucrat from Ottawa talking about funding the arts. I knew that when they mentioned music they weren’t thinking about me or any of my colleagues. Although governments seemed quite at ease with film and books, when it came to funding music they seemed to think only of opera and classical music. Even though popular music was turning out to be the most successful of all of the Canadian “cultural industries,” we remained chronically underfunded and mostly ignored.

So imagine my surprise when one day CHUM’s Bob Wood – yes, the same Bob Wood who had added “Wondering Where the Lions Are” to his playlist – came to see me at the True North offices, by then located at 98 Queen Street East. He had been talking to Tom Williams, who, with Al Mair, was a co-owner of Attic Records, located on the floor right above us. Tom had given Bob the idea of redirecting some of CHUM’s licence commitment money away from beneficiaries such as local student marching bands and putting it to better use directly inside the record industry. Radio broadcasters have always made various kinds of funding commitments to the CRTC as a method of insuring that they were able to receive and renew their licences. As a consequence, they were spending a fair buck on musical projects that had nothing to do with what they were broadcasting. The idea was to divert some of these dollars to a fund that would help the independents make more and better records.

I’ve got to say that I never liked the idea that we independents were making inferior records or that we weren’t making enough records. I thought there were plenty of good records out there, and that this notion of “we need more and better” was just a euphemism for “we’re never going to stop complaining about being regulated.” However, I would be the first to admit that it wouldn’t hurt if we could produce more and that we could all be better at what we do – radio included – so when Bob told me about the idea of redirecting some of his station’s benefit money, I jumped at it, as did all of us at CIRPA.

It took about a year of behind-the-scenes negotiations but finally, in 1982, this innovative idea – hatched by Tom Williams and Bob Wood and midwifed by radio and CIRPA – gave birth to a private, non-profit funding organization, FACTOR (Foundation to Assist Canadian Talent On Record). Officially, FACTOR was founded by CIRPA, CMPA (the Canadian Music Publishers Association), and three of the big Canadian broadcasters: CHUM, Rogers Broadcasting, and Moffat Communications. The idea was to provide support to Canadian artists, songwriters, managers, labels, and distributors through programs directed toward recordings, marketing, promotion, touring, and other aspects of the business.

In 1986, the federal Department of Communications in Ottawa finally decided to help popular music through the Sound Recording Development Program (SRDP). As part of this initiative Ottawa also began to contribute to FACTOR. This was a first in Canadian arts funding, as FACTOR became the first organization of its kind to be funded by both the government and private industry but run quasi-independently of Ottawa.

There is much more that can be said about all of this, and indeed about every one of the institutions that have helped in so many ways to propel the Canadian music scene forward. I don’t want to get bogged down in a lot of detail about the complexities and politics of funding, but one thing is certain, the many funding and regulatory initiatives have undoubtedly helped Canadian music to become more popular both at home and abroad. When I started in the sixties there were barely any well-known Canadian acts, and those few that there were, had, in almost every case, moved to the States. Today the number of successful acts has bountifully multiplied. Even though I sometimes regretted living in a world of reports and deadlines, brought on by a world full of funding regulations and bureaucracy, it remains certain that these institutions have worked. And there was still more to come.

Thinking back to this period, nothing is more important to me than the day, in 1980, that I met Elizabeth Blomme, who would become my wife and, by what can only be described as a miracle, remains my wife till this day. Remembering how we met brings a smile to my face. Late one afternoon I was on Yorkville Avenue, shopping at the Book Cellar just across the road from the Four Seasons Hotel. On my way to the parking lot I heard a voice calling my name. It was my old friend, and very first business partner, Peter Simpson. I hadn’t seen Peter, who had become a film producer, for some time, and when he asked me if I wanted to have a drink with him at the hotel, I was happy to join him. It turned out he was there doing interviews for Prom Night, which he had produced and was setting up to release. He invited me to hang out with Elizabeth, his publicist, while he finished up the interviews. For me it was love at first sight. Although it took a couple of years of both dating and living together, in April 1982 we were married. This was almost exactly twenty years to the day since I had surreptitiously helped Peter elope with his high-school sweetheart Gordine. Symmetry can be a wonderful thing and I’ve had plenty of it in my life, but my chance meeting with Peter that led to Elizabeth is certainly the most special of all those events. We have two wonderful boys, Edan and Noah, whom I love dearly.

There were professional milestones in 1980 as well. That year we put out the follow-up album to Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws. At the time, many considered Humans to be Bruce’s finest record. The first single, “Tokyo,” became a hit in Canada and a few other countries but didn’t do as well as “Wondering Where the Lions Are” in the States. Despite that, we were all excited about the album and its reception. There are many observations to make about that great record but what I remember most is that “Tokyo” was playing on my car radio the night of my first date with Elizabeth. I turned the radio up as loud as I could and proudly announced that this was on my label. At precisely that moment I was pulled over by the police. Apparently I had been repeatedly and precipitously changing lanes. The officer was quite nice about it, especially after concluding I wasn’t drunk or in any way incapacitated. He told me to park my car and walk home. Not the best way to start a relationship, but I walked Elizabeth back to her place and thankfully she had a sense of humour, so there was a second date. I’ve always thought “Tokyo” was a special record, but it will always occupy a very important place in my heart because of that night.

During that same year our management company signed another new act: Graham Shaw & the Sincere Serenaders. Graham’s first single, “Can I Come Near,” immediately went top fifteen across Canada, and we got a pretty good shot at the American market from Capitol Records, though as hard as we all tried, it just didn’t quite catch on there. Later that year, Graham won a Juno as most promising Male Artist of the Year. A year later we would do another album with Graham, but by the end of 1982 I would no longer be working with him or, for that matter, Bernie Fiedler. Change was once again coming my way, but at the time I was oblivious to it.

That same year, 1980, I sat down with my old friend Bob Ezrin, one the world’s top record producers, with credits as long as your arm, including world-class hits like Pink Floyd’s The Wall, Lou Reed’s Berlin, Kiss’s Destroyer, all of Alice Cooper’s early albums, and Peter Gabriel’s magnificent “Solsbury Hill.” You get the idea. Bob was as hot as you could get in our business without spontaneously combusting. He was back in Toronto and looking for something interesting to do.

Bob had an arrangement with Asylum Records that pretty much gave him an “open door” to bring in new projects. Asylum was then being run by Joe Smith, whom you’ll remember I had worked with during the time that he was with Warner Brothers and had signed Kensington Market. Bob told me that he had always liked Murray’s music and if he could produce the next McLauchlan album he would be able to guarantee us a contract with Asylum, the home of artists like Joni Mitchell and Jackson Browne.

It was an intriguing idea. The marriage of Bob and Murray in the studio might lead to something interesting, given Murray’s interest in rock and Bob’s continuing interest in Canadian roots music. Certainly the idea of getting Murray another strong shot in America with both a first-class label like Asylum and a world-topping producer like Bob was more than compelling. I set up a meeting for Murray and Bob and the chemistry seemed to be right, so we rolled the dice and took a shot. In a matter of weeks the deal with Asylum was done and we flew out to Los Angeles to do the inevitable signing ceremony and then shortly after began the recording process.

Now, as a manager, I knew this was a potentially risky gambit, and so did Murray. There was never any question of Bob’s ability or desire but he had never produced a Murray-style singer-songwriter and Murray had grown accustomed to producing his own records. Working with Bob was going to require Murray to give up a lot of control and take a leap into the unknown. But you never know what the results of anything are going to be and, let’s face it, we were nothing if not optimists. You had to be just to survive in this crazy game, and besides, the lure of another kick at the can in America was seductive.

So off went Murray and Bob, unfortunately not always in the same direction, and there was little I could do about it. There were lots of drugs being consumed during the sessions, which only helped to exacerbate the situation. Bob would sometimes show up to the sessions several hours late, which drove Murray crazy. Still, they soldiered on, and some of the record was turning out amazingly well. There was this one song Murray had written called “If the Wind Could Blow My Troubles Away.” It was like a little folk-hymn but by the time Bob was finished with it, it had become an immense full-on cathedral anthem.

Murray McLauchlan signs with Asylum Records. From left to right: me, Kenny Buttice (Asylum A & R), Murray, Bob Ezrin, and Joe Smith

I really liked that cut, and thought it might have a real chance to break Murray through in the States. When we delivered it to Joe Smith and the Asylum staff they seemed pretty excited about the song’s chances. Asylum worked the record, but when little happened right out of the gate, they soon gave up promoting it, and unfortunately the record just didn’t have the right spin to work on its own. The last time we tried a similar move it had led to “Farmer’s Song.” This time we just didn’t get as lucky. Storm Warning was the title of the album, and it was aptly named.

By 1982 I felt my life had changed. The music business, which I had fallen into almost by accident, had become all-consuming. Elizabeth and I had married. Having watched the constant breakups and heartache that plagued the personal lives of so many of my friends I was determined to give us a real chance. I was also questioning my ability to continue working with Bernie Fiedler. It had been an intense ten years that had brought many rewards and wonderful times but also the inevitable friction that can occur between partners under any circumstances, particularly when they’re involved in the high stakes and constant pressure of the music business. As hard as it was, I came to the conclusion that the time had come to end our partnership. My thought was that this would reduce my workload, freeing up time for my family.

When I approached Bernie about the two of us going our separate ways, he really didn’t fight it. I think he had probably gotten sick of me as well. The breakup went smoothly enough, although informing the acts was not easy. The plan was that I would keep True North Records, Murray, and Bruce, while Dan Hill and Graham Shaw would go with Fiedler. We made our deal, and although I’m not entirely sure how the artists truly felt about this new reality, I did have long private talks with each of them and no one expressed any deep reservations about it.

I was now on my own for the first time since 1972. It had been a great run; not without its disappointments, of course, but by and large it had been a remarkable and extremely productive time. I realized that I was now over an urge that seemed to have been deeply imbedded in me by my air force upbringing – to pick up and leave whatever I was doing every couple of years. Finkelstein-Fiedler had lasted a decade, and I had been working with Bruce for thirteen years and with Murray for twelve. That’s a long time in the very fickle music business.

I kept my office on Queen Street East, which was right across the road from CityTV. City was a remarkable station run by my old acquaintance Moses Znaimer. I had first met Moses back in my early days when we were doing the early True North recordings at Thunder Sound. By 1982, he had not only become the pre-eminent television entrepreneur in Canada but also a kind of broadcasting guru. City was doing things no one else had even thought about – including lots of innovative music programming – and from time to time I would drop by the City studios to check in on what Moses and his gang were up to.

We had all been closely watching the new marvel of music videos. MTV had launched a year earlier. It was becoming very successful while revolutionizing the music business, with its concept of providing an outlet for the new promotional medium of music videos, interspersed with occasional live events and music business news. The combination of TV exposure with radio airtime was a new phenomenon in the culture and turned out to be a potent force for selling records.

The CRTC had scheduled a hearing, with the aim of licensing one or two music channels in Canada. Moses was going to be one of the applicants for a licence, which made sense as City was already playing music clips on many of its programs. I had been approached by several different groups to take a role in their applications and had actually accepted a position with a group headed by Allan Gregg, the well-known pollster and political commentator, and Bev Oda, who today is a Conservative federal cabinet minister. As the hearing date approached, Allan and Bev’s group lost their funding and dropped out of the upcoming hearings in Ottawa. This was disappointing news, but I quickly went across the road to meet with Moses and asked him if there was anything I could do to help with his application for “MuchMusic.” We quickly cooked up an idea that would eventually become VideoFACT (the FACT standing for Foundation to Assist Canadian Talent).

I’ve always been very proud of my role in VideoFACT. All of the applicants for the music channel were promising to play Canadian videos, but there were hardly any Canadian videos to play. Moses and I estimated that at the time of the hearings there were only twenty-two Canadian videos suitable for airplay. Our solution was simple and elegant: MuchMusic, if licensed, would commit to putting a percentage of its gross revenue into a fund that would be solely dedicated to financing Canadian videos in both official languages. We carefully developed the plan right down to the last detail. Our fund would be independent from Much but would include a couple of board members from the channel. I would be the first chair of VideoFACT, a role I figured I might take on for a few years to ensure that it got off the ground in the right manner. So I went to Ottawa with Moses and the rest of his team to appear in front of the commission and present the VideoFACT idea to the CRTC. It was a memorable event. I clearly remember the impressive and dedicated staff Moses had assembled for the proposed channel, especially John Martin, who would go on to become Much’s first program director. For John and several of his colleagues, music television seemed to be a matter of life and death, which I found inspiring.

The first board of VideoFACT. Seated, from left to right: Sylvia Tyson, me, and Victor Wilson. Standing: Robert Brooks, John Martin, Moses Znaimer, and Pierre Boivin

At the time, City was largely owned by CHUM, so during the hearing I also worked with Allan Waters, the founder and owner of CHUM. Although we often had been at odds regarding Canadian content, I found Allan to be personable and easy to get along with. The CHUM group, consisting of Moses, Allan, and the rest of the team, was a formidable force. We arrived in Ottawa a few days early for rehearsals, which were organized to be as similar as possible to what the hearing itself would be like. CHUM brought in Jerry Grafstein (later Senator Grafstein) to play the role of a commissioner running us through the potential questions we might be asked. At one point, Jerry put a question to me that might have had any one of several answers, so I asked him what the right response might be. Allan jumped in and told me and the assembled group that the right answer was always the truth; that was what CHUM stood for. I was impressed with his candour, and my opinion of him, which was already high, jumped up a few more notches.

Finally the big day of the hearing came. I remember sitting in front of the commission and glancing back at the rows of seats behind me. I didn’t see a single person from the music business, even though this hearing was arguably the most important industry event since the Canadian-content rules in 1971. When Much finally went to air in April 1984, and I would hear the not infrequent complaints levelled against it, I always wondered where these people were when they had the chance to make an impact on the outcome.

Our presentation went very well and the VideoFACT part of the proposal seemed to be a big hit with the commissioners. About six months after the hearing ended, we were informed that the CHUM group had been successful and that the commission expected MuchMusic to live up to its commitment to start a fund to finance Canadian videos, with me as its first chair. In our first year we had a budget of $100,000. Over the years that has grown to an annual budget in excess of $4 million. With no minimum distribution or sales requirements, VideoFACT has always taken a leading role in funding independent Canadian music. We ask only that the applicant be Canadian and that the song and video meet the Canadian-content rules. As a consequence we have often been at the cutting edge of support for up-and-coming young artists who at the time of our approval were essentially unknown: artists like k.d. lang, Arcade Fire, Barenaked Ladies, K-os, Celine Dion, Sam Roberts, and Sarah McLachlan. I remained Chair of VideoFACT (now known as MuchFACT) until February of 2011 when I finally stepped down to make room for new blood. MuchFACT has now spent over $65 million on videos and websites and funded some 5,400 different projects. Moses is no longer involved in the station and, sadly, John Martin has passed away, but I have fond memories of those early board meetings. We had fun and at the same time we thought we were making a difference.