CHAPTER FIFTEEN

For the first time since I’d managed the Paupers at the beginning of my career, I was back to managing just one act: Bruce Cockburn. Not that I didn’t have plenty to do. Bruce was having a commercially successful run and it seemed as though he was always on the road somewhere in the world, performing concerts in Germany, the U.K., Italy, Australia, and America. And often I was there with him. Italy was a particularly interesting place to play. There was a certain kind of casual approach to presenting a show there that was, well, quite foreign to just about everything I had trained myself to do.

A manager has many duties and one of them is to make things work on time and according to a schedule. I’ve often thought that if a bicycle tire was a metaphor for the music business then a manager would be right at the wheel’s hub, along with the artist, and each spoke going outwards would be a different discipline within the business. One spoke might represent accounting, another might represent promotion, and yet another booking shows, and so on. And although a manager is not necessarily doing each of these different things by himself or herself, he or she would have to be conversant with them all and be able to hire and work with the right people in all of these specialized areas.

One of our tours in Italy tested the idea that things had to happen on time. One evening before Bruce’s show in Milan, our Italian promoters were treating us to a particularly fabulous meal. (I might add that it’s almost impossible not to have a fabulous meal in Italy.) The show began at 9 p.m. During the meal I took a quick look at my watch and was startled to see that it was 8:45. I anxiously pointed this out to our hosts, but they were not alarmed at all, and they assured us that the three thousand people waiting in the venue would agree with them that enjoying our meal was more important than getting on stage on time. Both Bruce and I were quite taken aback by this, but the promoters turned out to be right, at least that night, because the show was a huge success. Things have changed now in Italy, so fortunately we didn’t pick up the habit of being late – in fact, Bruce rarely eats before a show – but that was an exceptionally memorable evening in Milan.

Me and Bruce fooling around at Tivoli Gardens, in Copenhagen (1980)

I continued to run True North and had by now built up a tidy little catalogue of around eighty albums. I had taught myself to treat that catalogue like a garden. I knew if I looked after it properly, it would continue to grow and flourish, so I tended to it every single day, making sure the albums were available everywhere possible and that the songs would be available for other uses.

Also, I continued to serve on many industry-related boards: CIRPA, VideoFACT, Massey Hall, and others. One of the most interesting was the Ontario Film Development Corporation (OFDC), today known as the Ontario Media Development Corporation (OMDC). I had been asked to join the board by Wayne Clarkson and Bill House. Wayne had run Toronto’s Festival of Festivals in its infancy (today the Toronto International Film Festival, or TIFF), and was about to become the first chairman and CEO of the OFDC when it launched in 1986. I had met Bill, a veteran film producer who was to be executive coordinator of the new agency, when he approached me to do a film about Bruce. Although we had grand ideas for creating a full-blown documentary, we had to settle for a concert film, Rumours of Glory. Nevertheless, it’s a wonderful film made by the award-winning dramatic and documentary director Martin Lavut.

I was floored when Bill and Wayne asked me to join the board. It included such luminaries as Adrienne Clarkson, director Norman Jewison, and long-time broadcasting executive Peter Herrndorf, among others. When I asked Wayne and Bill why they wanted me, they replied “Sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll.” Aha, I thought, we’re being noticed. I loved serving on that board. I was immediately appointed to the executive committee and had the satisfying experience of seeing, from the inside, another arts organization grow from its inception. The OFDC was also a tremendous learning curve for me. To date most of my experience had been related to the music business. Now I was surrounded by a smart group of people from not only the film business but also many other areas of Canada’s cultural and business worlds, and they had plenty to teach me. The OFDC was, at that point, directly funding some of Ontario’s emerging young talents, and it impressed me the way that Wayne, Bill, and the staff at the OFDC were picking some real winners, among them Atom Egoyan, Patricia Rozema, and Bruce McDonald.

But not everyone at True North was as satisfied with the status quo as I was. Jehanne Languedoc, who was pretty much my whole support system, was forever fielding calls from musicians looking to hook up with me in one way or another; she was adept at moving them on to more likely situations, since I’d made it clear that I wasn’t interested in working with new talent. Still, I think she knew me well enough to sense that I might be getting restless. She kept talking to me about an artist from Vancouver named Barney Bentall who, with his band the Legendary Hearts, was starting to make some noise on the West Coast. Jehanne was convinced that Barney was going to be big and kept giving me demos to listen to, which I kept ignoring. One day in 1987 I was having lunch directly across the road from my office at a fine little café called Emilio’s. Was it a coincidence that Jehanne just happened to be eating there with Barney? She casually walked over to my table with him in tow and introduced us. I saw why Jehanne was so high on him. Barney is one of the nicest and most charming people I’ve ever met; it was hard not to instantly like him. I made a note to listen to his demos that evening. I liked what I heard and made arrangements to meet with Barney before he returned to Vancouver.

As it turned out, my good fortune was that CBS/Sony was considering signing Barney to a record deal at the same time that I initiated talks with him. True North was still being distributed by Sony (Sony had bought CBS but my distribution deal hadn’t changed) so there was great synergy between our two companies and I quickly came to the conclusion that if I was going to expand again, having Barney directly signed to Sony would be a good thing for both the artist and me. I would represent Barney for management and publishing while Sony absorbed part of the burden of start-up costs. Barney had a terrific video for his song “Something to Live For,” which was already being played on MuchMusic. There seemed little doubt, at least in my mind, that this song could be a hit if worked properly.

Once the deals were signed, we embarked on recording Barney’s debut album and commercially releasing the first single. I wasn’t surprised that “Something to Live For” became quite a hit. In fact the album, entitled Barney Bentall & the Legendary Hearts, eventually went platinum. We would go on to do four albums together, all of which went gold, while two reached platinum sales. Barney had a string of Canadian hits, including “Come Back to Me,” “Life Could Be Worse,” “Do Ya,” and, of course, “Something to Live For.” He was always a pleasure to work with and I owe Jehanne a great debt of gratitude for keeping after me to work with him.

In 1989 Barney and the Legendary Hearts won a Juno for Most Promising Group of the Year and we were set to have the self-titled debut album released in the U.S. At this point, CBS in the States was being run by Donnie Ienner, my old friend from back in the days of Bruce’s “Wondering Where the Lions Are.” Bruce’s records were being released in the U.S. on Jimmy and Donnie’s Millennium Records, but their company had begun to run into financial troubles in 1981, right around the release of Inner City Front. That’s one of the ever-present dangers in the independent record business – you work with some very creative and fabulously talented record people but there is the constant threat of money problems. One day I got a call from Jimmy informing me that he was going to close down Millennium. I immediately got on a plane and headed to Manhattan. I’m sure that this was a very trying time for the Ienner brothers and I wanted to let them both know how much I had appreciated the great job they had done for us. I wasn’t there to complicate their lives any further but to see what I could do to get back the U.S. rights to our Cockburn masters. I think they were quite pleased that I wasn’t there to pour oil on the fire, and we quickly worked out a deal to get our records back. As you’ll see shortly, I would later resell those very same records to Donnie after he began running Columbia Records.

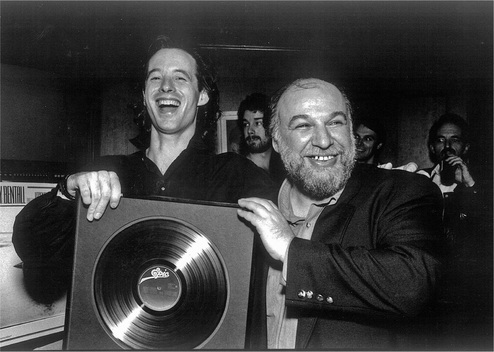

Barney Bentall gets the first of his four gold records

With Barney awaiting the release of his album in the States, I arranged for both of us to be guests of CBS at its annual international convention, being held that year in Boca Raton, Florida. This would be a great opportunity for Barney to meet a lot of the key people who would potentially play an important role supporting his international career. Only a selective number of CBS artists attended this exclusive convention, so the fact that Barney had been invited was an indication of the company’s support and, because of Barney’s winning personality, it had the potential to be an important event for him. The first evening was an introductory dinner with around four hundred CBS employees and their guests in attendance. While I was watching one of the acts performing onstage, someone came up behind me and put their hands over my eyes. It was Donnie Ienner, newly installed as President of the Columbia Records Group. We had a happy reunion. He liked Barney, as I suspected he would, and we quickly agreed during the convention to have Barney do a promo tour of some of America’s key radio stations.

Then, unexpectedly, Donnie asked me what Bruce was up to. I explained that we were just ending our contract with Gold Castle, and Donnie asked me to contact him in New York after the convention. When I did, he made me an offer to start releasing Bruce’s records in the U.S. on Columbia. It didn’t take too long to work out the details and so, just like that, Bruce’s records were being distributed on the most powerful label in America. While he was still signed directly to True North, we would now license our next several records to Columbia in America as well as other parts of the world. At the same time, we made another deal with Donnie for Bruce’s available back catalogue – basically licensing back to Donnie the same albums that I had licensed to him at his previous company, Millennium, including Dancing in the Dragon’s Jaws. I would eventually get those records back again, when we left Columbia several years later. Each time these records changed hands, both Bruce and I made money, and, even more importantly, the records received another lease on life and more shelf time in record stores around the world.

Working with Columbia was interesting, chaotic, and fun. It was a large company but there were lots of terrific music people who were in the business for all the right reasons. With their help, Bruce hooked up with producer T-Bone Burnett, already admired for his work with Los Lobos and Elvis Costello. Years later T-Bone would break through to wider public acclaim with his production of the Grammy-winning soundtrack to Joel and Ethan Coen’s film O Brother, Where Art Thou as well as of Raising Sand, the Grammy-winning 2009 collaboration between Alison Krauss and Robert Plant. Bruce would do two albums with T-Bone – 1991’s Nothing But a Burning Light and 1993’s Dart to the Heart.

By the early 1990s, a whole new radio format, called Triple A, or Adult Album Alternative, had begun to catch on in the U.S. Simply put, it was music from the fringes of the mainstream aimed at a more mature audience whose taste in music hadn’t drifted to the middle of the road. It wasn’t quite the free-form radio of the sixties but was better, in my opinion, than the staid and overly formatted choices being offered elsewhere on the dial. Sadly, Triple A barely existed in Canada; there might have been one or two stations at any one time here, compared to more than one hundred in the States. Ironically, many of the artists getting exposed in the American Triple A universe were Canadian, among them Cowboy Junkies, k.d. lang, Barenaked Ladies, and Bruce. With the muscle of the American promotion team behind him, Bruce had several of his songs make the top five in this format.

One of the most interesting records we did during our Columbia years was Bruce’s Christmas album released in 1993, titled simply Christmas. It was one of the few times Bruce produced himself and the album is a wonderfully eccentric mix of songs that includes “The Huron Carol” sung in the original Huron language and an obscure gospel number called “Mary Had a Baby.”

Our experience with Columbia makes me think about how it’s become quite fashionable to slam the large record companies. Those companies get hit with accusations ranging right across the spectrum, everything from blatant thievery to ruining good music to being populated by idiots who can’t see where the future lies. If it’s true, you wouldn’t know it from my experience. Sure, the deals were not always fair, and they did make the companies and many of the entrepreneurs and executives rich, but they also made many of the artists rich, and brought their music into millions of homes. I’ve been an “indie” all my life and I’m proud of it, but I don’t need to see the major companies attacked to feel good about what I’ve done. There is no doubt that today everything is in flux and the hold the multinationals once had on the marketplace is slipping. Maybe that’s a good thing, but we’ll have to wait and see what the new model brings, especially where it counts the most: with the music.

In the early 1990s I signed two brilliant songwriters to True North: Gregory Hoskins and Stephen Fearing. They were unique artists, and although I would only make two albums with Gregory, I would have a sixteen-year relationship with Stephen.

I always considered Stephen to be a very special talent and it was a constant disappointment for me that I couldn’t break him bigger than I did, although I think I helped him have a consistently rewarding career in music. Stephen did bring to me one of the most fun projects I have ever been involved with – Blackie & the Rodeo Kings. And to think, I almost turned it down.

One day in 1996 Stephen called to tell me about an idea that he and Colin Linden had come up with and to see if I’d like to get involved. Just to back up for a moment, Colin was someone I had known or known about for most of my life. He would come to the Riverboat with his mother when he was just a kid and also show up at many of the shows we were promoting at Massey Hall. Colin was something of a child prodigy, an amazing guitar player with an encyclopedic knowledge of music, both its history and the players. This was especially true when it came to his first love, the blues.

When Bruce made Nothing But a Burning Light with T-Bone Burnett, he hired an all-star band that included Booker T. Jones of “Green Onions” fame, drummer Jim Keltner, and bassist Edgar Meyer, whose credits range from Alison Krauss to Yo-Yo Ma. When it came time for Bruce to tour, we were not going to be able to get these very, very busy studio musicians to go on the road with us at the drop of a hat, so Bruce suggested that we call Colin Linden, who knew the best roots players in Canada. In the end, we used Colin’s band and spent a couple of great years on the road together. Bruce went on to use Colin’s band as his studio group for Dart to the Heart. Eventually Colin succeeded T-Bone as Bruce’s producer and made several albums with Bruce, including what I consider one of his best, The Charity of Night.

However, when Stephen called me to say that he and Colin had been kicking around the idea of forming a group to record a tribute album to songwriter Willie P. Bennett, using as the name of their band the title of one of Willie P.’s songs, I was less than impressed. Fortunately for me, I agreed to have lunch with Stephen, Colin, and Tom Wilson. Tom, who was going to be the third member of Blackie, is a big, talented, lovable guy you could easily mistake for a biker. He had already received one gold record for his work with the group Junkhouse. By the time the four of us had finished lunch I was completely sold on the idea of Blackie & the Rodeo Kings. (A little-known bit of trivia: I became known as Blackie, a title I kept until I stopped working with the band in 2007.)

Willie P. Bennett was truly one of the great songwriters of his generation and I had almost completely missed him – another reason to keep an open mind and listen to the musicians you work with. So even though I was unable to get Stephen the hit records I think he deserved, I was able to get him some airplay with the Blackie project. Indeed, both Stephen, as a solo artist, and Blackie & the Rodeo Kings would go on to win Juno Awards.

Working with Blackie was a joy. Sure, it was chaotic, and coordinating the schedules of the three principals could be maddening, but the music was always stimulating. I’m confident that had the three of them come along in the late sixties or early seventies, they would have been a huge success. As it was, they’ve done quite well, and it was always fun to work with them. Certainly they made some of the best records, and did some of the best live shows, that I had ever been involved in. But the business had now changed, and to be truthful I was having trouble finding the key that would unlock those doors and take a group like this onward to bigger and better things.

The world had moved on, as it must, and although I think I changed along with the times, I was finding it harder to keep the music I loved in the public eye. Nonetheless, True North continued to grow. I started releasing music from around the world, no longer restricting myself to Canadian records. By doing this I ended up putting out music by such greats as Richard Thompson, Echo & the Bunnymen, Shawn Colvin, Kelly Joe Phelps, Jethro Tull, and many others. The growth wasn’t only confined to foreign acts. I also released records by Canadian acts such as the Rheostatics, Moxy Früvous, Zubot & Dawson, 54-40, Howie Beck, Lynn Miles, the Golden Dogs, Randy Bachman, and the late jazz guitarist Lenny Breau. By the new millennium, True North had grown from a scrappy one-man band in Canada’s infant music business into one of the country’s biggest and most successful independent record companies.

Blackie & the Rodeo Kings (Colin Linden, Stephen Fearing, and Tom Wilson) help me celebrate my induction into the Music Managers’ Honour Roll (barryroden.com)

By the time I sold True North we had put out over five hundred albums and countless singles. True North had collected more than forty gold and platinum albums, and around fifty Juno Awards. Our artists had received almost every type of award there was and many of them had become so well known that they were icons in the music business. But for me, it felt like my time had come and gone. Yes, I could still compete, and on any given day I could do my job as well as anyone anywhere in the world. In fact, on a good day I was even unbeatable. But I had promised myself many years ago when I was starting out that if I ever began feeling that I would rather be somewhere else more often than I felt like being at work, I would find a way to get out of the business. And sure enough, that day had arrived. But before that time came, I had to spend some time in the hospital with a heart condition that almost killed me.

For years I had abused myself with everything from drugs to overeating. I’d been mostly sedentary and had never bothered with doctors or annual checkups. I suppose I was lucky to be alive. By 2005, though, I had been noticing that I was frequently out of breath. It was particularly noticeable when I was arriving at airports. I would leave the plane and start the long trek towards the baggage claim area but would almost always have to stop, put down my carry-on bag, and catch my breath. Nonetheless, I ignored these signs, until early one morning when I woke up and immediately vomited. Given that I hadn’t been out drinking the night before, the message finally sank in. Something was wrong. I called the office of the last doctor I’d visited and miraculously convinced his assistant to have the doctor see me that morning. Elizabeth drove me to the appointment. The doctor checked my heart rate, then took my blood pressure, and before he had even removed the inflatable cuff he told me that I should go immediately to the nearest hospital. My systolic blood pressure was up near 200 and he felt I could have a cardiac event at any moment.

We drove downtown to Mount Sinai, the hospital where I’d been born sixty-one years earlier. Of course, it had relocated to University Avenue from Yorkville decades before. When I presented myself at the emergency department that day, I hadn’t been near a doctor for over five years and hadn’t been in a hospital, other than for the odd broken finger or toe, for some forty years. When the admitting doctor asked me who my physician was, or if I had any idea of where my medical records might be, I wasn’t able to give him anything. Furthermore, he wasn’t able to find a single bit of information from the medical system citywide. The first thing he told me was that I was about to get my “money’s worth” from Canada’s medical care system. It took a few hours, but finally I was admitted.

How serious was it? I was in the hospital for close to two months. While there I had a quadruple bypass and a heart valve replaced. I was told the night before my operation that I was a bit of a high-risk patient and that I had the option to delay the operation for a month or so while I lost more weight and generally got into better shape. The surgeon told me that the normal odds of success for my kind of surgery were about 95 per cent but that in my case it was more like 85 per cent. I told him that in my world 85 per cent odds were better than anything I was used to and that we should go ahead as planned.

I’d like to tell you that I had an epiphany while in the hospital but I didn’t. I did get control of my weight to some degree and I certainly cleaned up a lot of my bad habits. But as far as my working life, I didn’t really come to any conclusions. In fact, I booked a ten-city tour for Cockburn from my hospital bed while attached to a morphine drip. (Turned out to be a good little tour, too.)

No, it wasn’t until well after I left the hospital that I came to the conclusion I should make a change.

I had come face to face with the fact that for me the music business was no longer the fun it had been. In some respects I’d been hoisted by my own petard. I was now spending more time filling out grant applications and collecting backup material than I was in the studio. I was spending more time listening to my employees’ problems than listening to music, and I was constantly trying to figure out how to keep the business going and growing, in a climate that was less and less conducive to growth, at least for someone with my skill set. Simply put, my due date had come and gone, and I had to do something about it.