One

POTATO CREEK

STATE PARK

The iconic Naragon’s barn is one of the few remaining landmarks of the farming community once located inside the property of Potato Creek State Park. The barn, which was built by Charles Naragon in 1908, sits at the edge of Lake Worster. It stands as a quiet testament to the hardworking farmers who tilled the soil for generations before the creation of the state-owned park. (Photograph by and courtesy of Shelly Platz.)

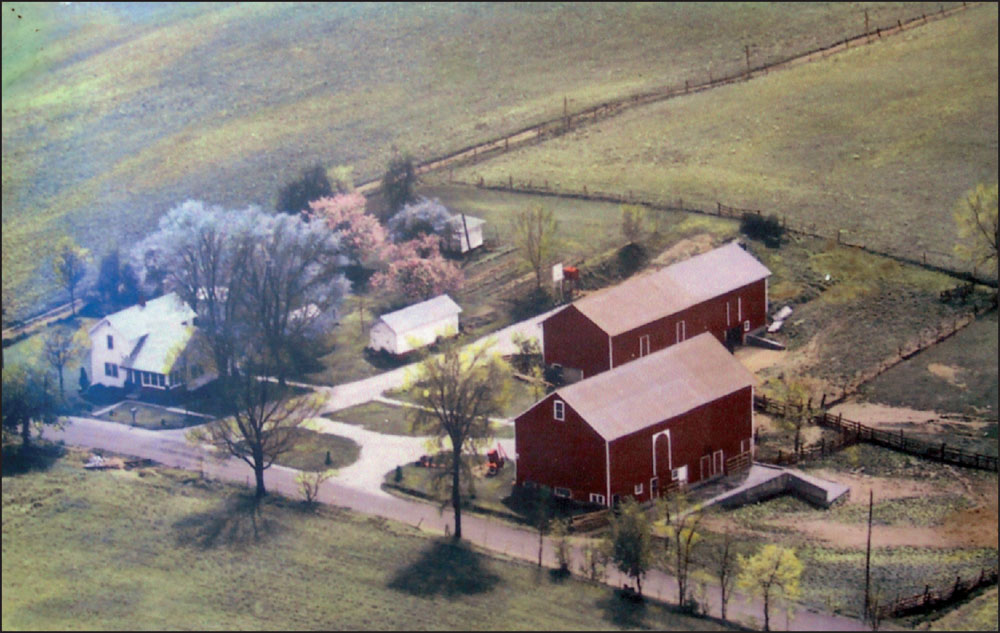

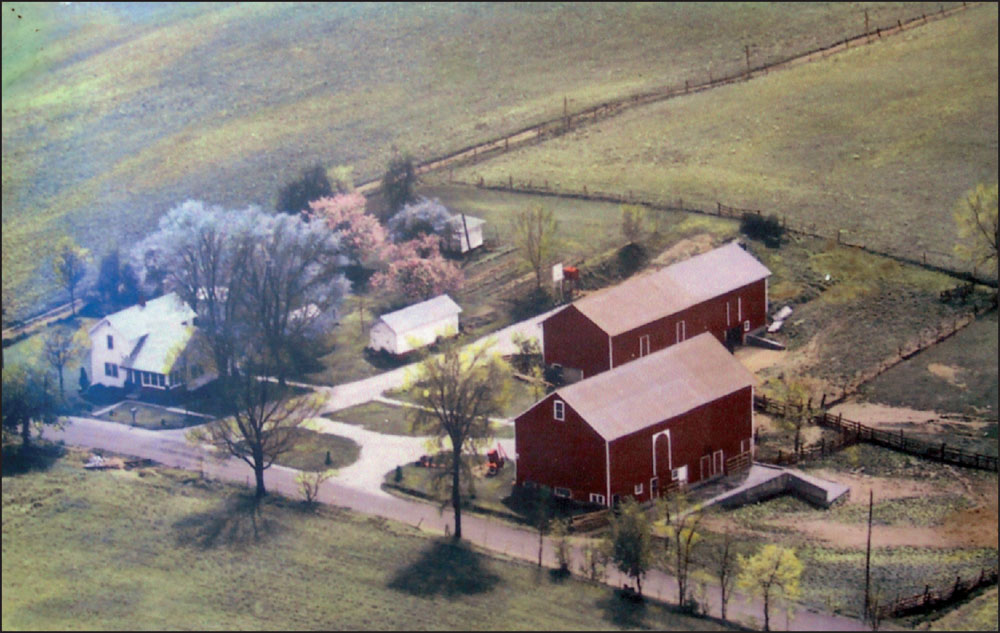

When heavy rains fell, the lowlands surrounding Potato Creek had to be drained via cement drainage tiles. In 1991, Raymond Naragon recalled, “When you get 40 acres of ground covered with water, that was the only way the water got out was through the tile. It was like a gusher coming out of [the tile] down at the creek.” This aerial photograph of the Naragon farm was taken in late 1960s. (Courtesy of Esther Naragon Shoue.)

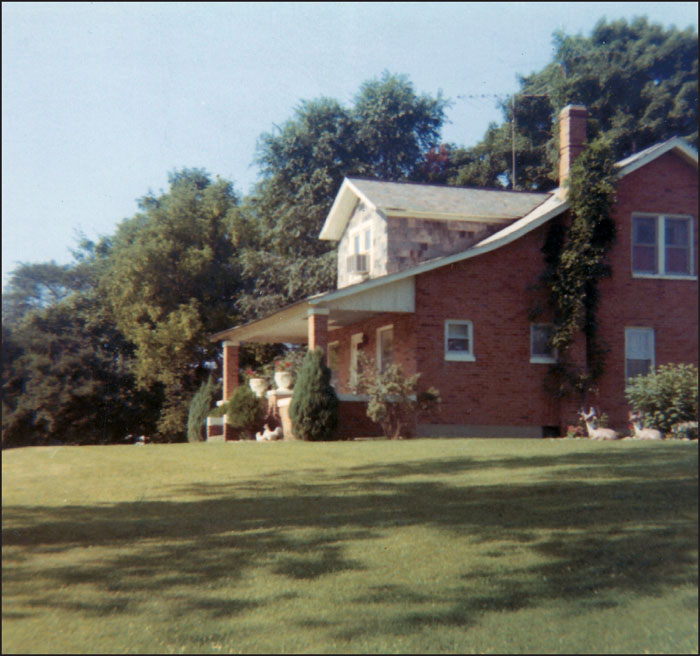

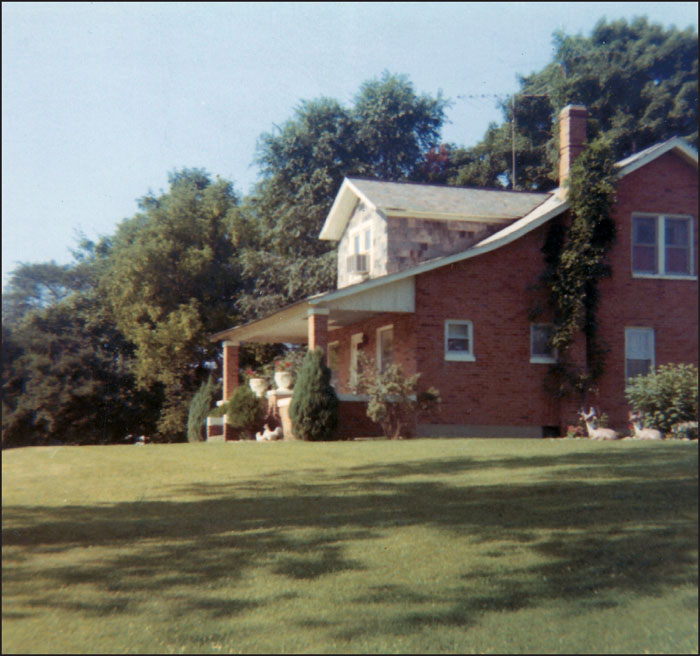

Four generations of the Naragon family lived on the Naragon homestead, located on Primrose Road. The Naragon family settled in the area in the 1850s after migrating from Ohio. This image shows Raymond and Dorothy (Keiser) Naragon standing in front of the family home in the early 1960s. Their daughter Esther Naragon Shoue fondly recalled that her mother planted flowers “anyplace that would grow them.” (Courtesy of Esther Naragon Shoue.)

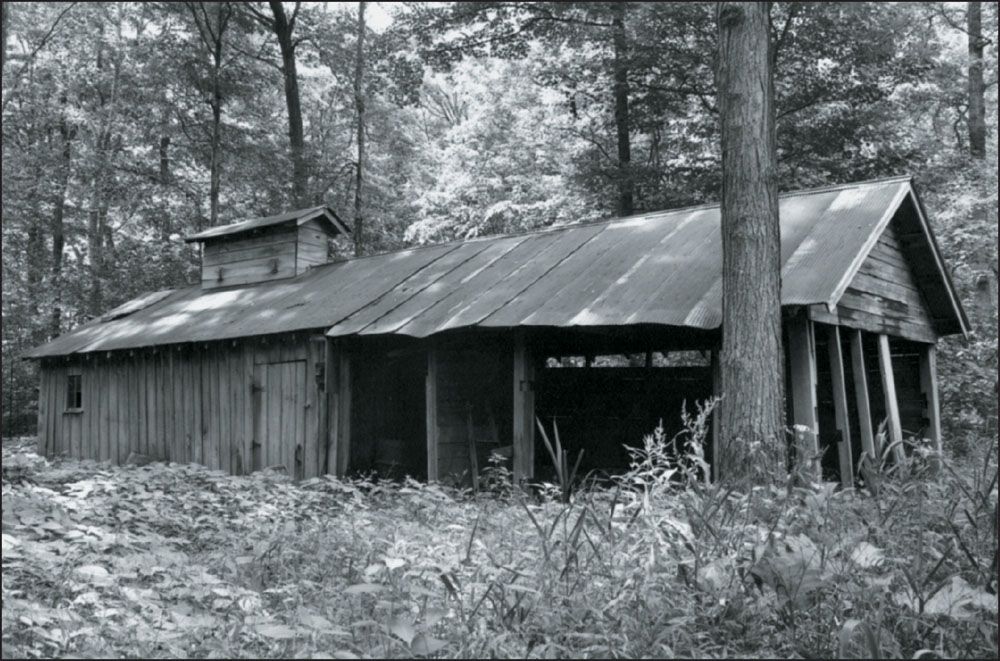

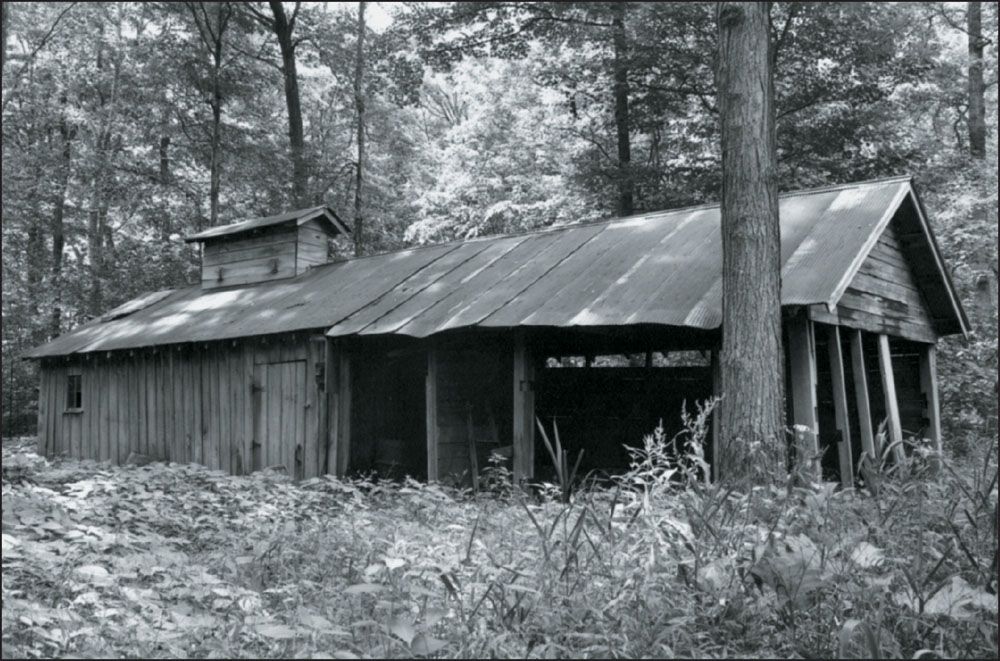

Six families operated maple sugar camps in the Potato Creek area, including the Cullar, Kane (formerly owned by the Amm family), Naragon, Robertson (assisted by the Fullmer and Borton families), Schrader, and Sheneman camps. The Naragon camp, built by Raymond Naragon and one of his brothers in the 1940s, is pictured here; it sat near the present-day location of the Peppermint Hill Shelter. (Photograph by Tim Garbacz; courtesy of Potato Creek State Park.)

Working the land was an essential way of life for many families. Sheryl Beron Yoder, granddaughter of John E. and Edna (Wilkeson) Beron Sr., recalls, “Grandpa used to grow and sell strawberries to make extra money. My grandma made and sold peanut brittle [at] Christmastime.” The Beron family home, located on the corner of Oak and Osborne Roads, is shown here in the winter of 1960. (Courtesy of Sheryl Beron Yoder.)

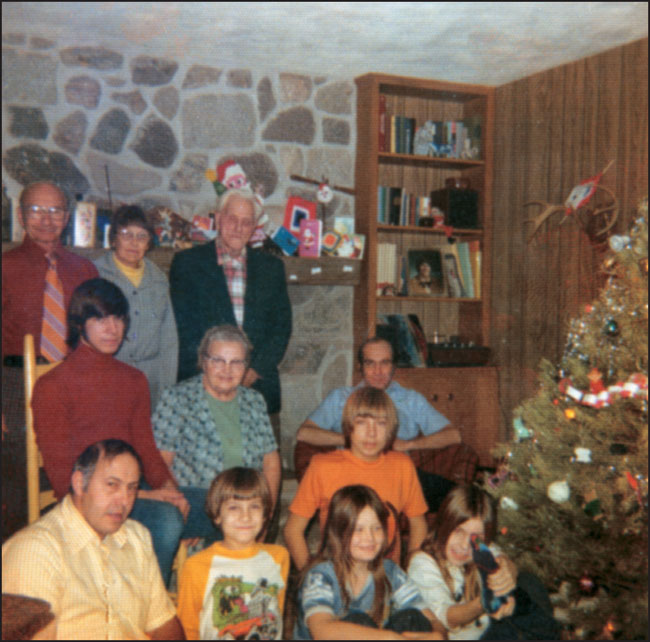

The Bortons are another family whose roots ran deep in the park area. The family members of James and Helen (Nelson) Borton pictured here in 1966 are, in no particular order, Merle, Ray, Mable, Lawrence, Lynn, Terry, Keith, Ruby, Jan, Jim, Lester, Linda, Mary, Dale, Lyla, Alma, Iona, Helen, Korin, Louann, Denise, Toney, Zella, Robert, Mary, Ray, Sandy, Pork, Vickie, Carl, John, Matt, Luke, Nancy, Mark, Velma, Alice, and Glen. (Courtesy of Linda Whitmer Borton.)

Maple sugar season begins in February and lasts four to five weeks, coinciding with farmers’ downtime. Sugar water is gathered by tapping maple trees, and the sap is then repeatedly boiled down to make syrup. Jim Borton is pictured here on an unusually warm spring day as he gathers sugar water from the trees. (Courtesy of Linda Whitmer Borton.)

In 1935, Charles Howell volunteered to tear down the abandoned one-room schoolhouse known as the Rea School, which sat on the southeast corner of Pine and Osborne Roads. Howell repurposed the bricks to build his farmhouse, pictured here in the late 1960s. Howell’s home stood on Pine Road in the current location of the service station for the park. (Courtesy of Kelli Fuchs Mann.)

In the 1960s, Karl and Dolores (Krusinski) Huff were living at the Howell homestead. In 1963, Karl, the grandson of Charles and Grace (Jackson) Howell, tore down the barn built by his grandfather and constructed the one shown here. (Courtesy of Kelli Fuchs Mann.)

The family of Franklin and Beatrice (Banks) Sheneman lived on the far western side of the park area on Redwood Road. Franklin was a farmer with over 50 head of sheep. The family is pictured at left in the mid-1950s. From left to right are Beatrice, Franklin, John A. II, Roland, and Dale. Franklin ran a sugar camp and sold his pure maple syrup out of one-gallon metal containers (pictured below). A favorite tradition of the children at the Sheneman sugar camps was boiling hot dogs in the maple water to give them a hint of sweetness. Maple sugar candy was also a perennial favorite. After Franklin’s death in 1965, Beatrice “Beatie” Sheneman worked at the North Liberty drugstore’s lunch counter for 25 years, serving her famous ham salad sandwiches and fountain drinks. (Both, courtesy of the author.)

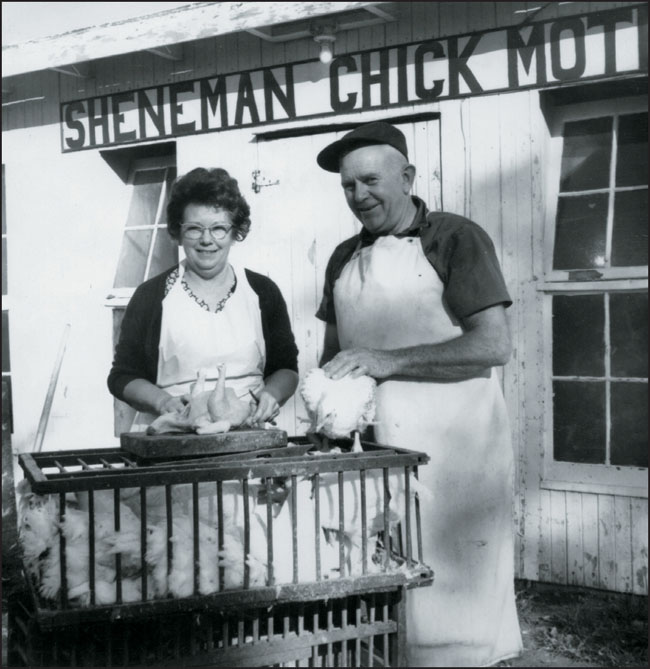

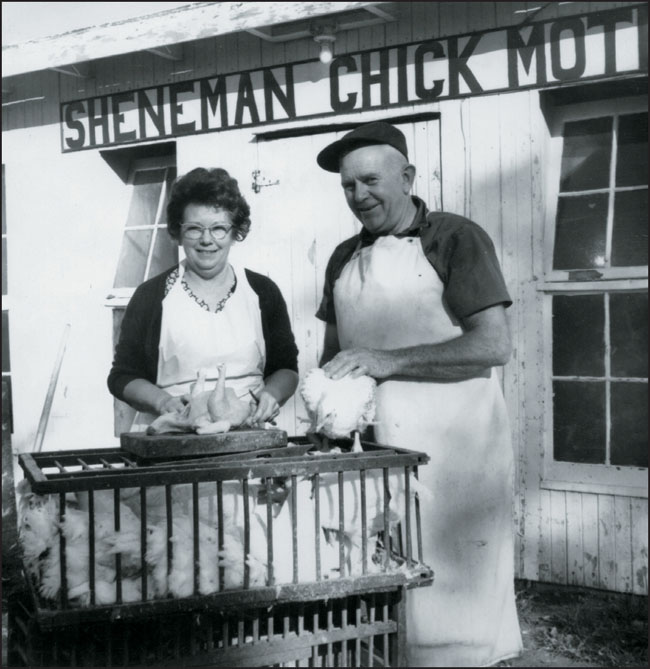

Claude and Gladys (Thayer) Sheneman lived on the corner of Redwood Road and State Road 4. Gladys recalls starting their chicken business in the 1940s: “We purchased two brooder houses and bought chicks from Birkey Hatchery in Bremen. Each year, Claude would build a room on until we had six rooms and a dressing room.” It became known as Sheneman’s Chick Motel and was sometimes mistaken as a place for travelers to lodge. Claude and Gladys (right) are shown dressing their last chickens on October 19, 1970, after selling their property to the state. (Courtesy of Gladys Sheneman.)

In addition to their chicken business, Claude and Gladys Sheneman had a large grove that could be rented for reunions and various events. They were also known for their elaborate Christmas displays. (Courtesy of Gladys Sheneman.)

The home of Albert and Leona (Arnold) Schrader was located on Osborne Road, and their son Wayne built a home next to theirs on the corner of Osborne and Pine Road. Ashley Schrader said, of his time spent growing up there, “I was too young to work on the farm, but I played from one end of it to the other.” The park recently rebuilt the Schrader Springhouse. (Courtesy of Ashley and Diane Whitmer Schrader.)

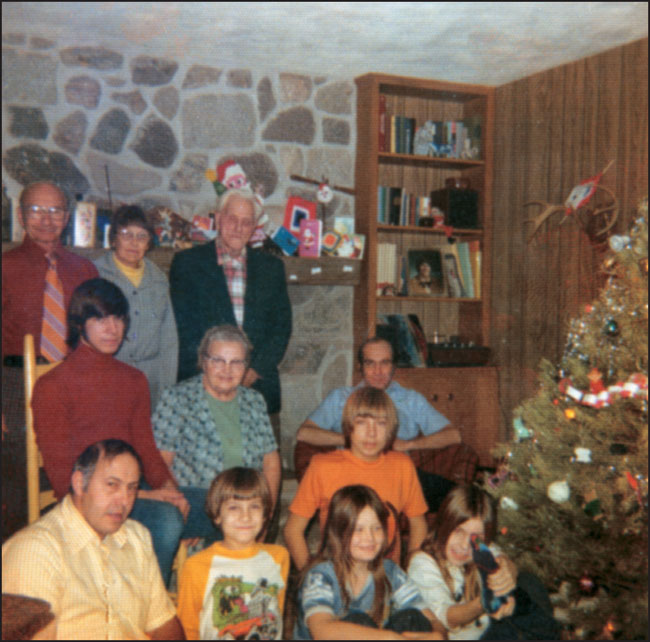

After selling their land to the state, neighbors Wayne Schrader and Gary Hall built homes next to each other between North Liberty and Lakeville. Pictured here in the 1970s are, from left to right, (first row) Wayne Schrader, Nicholas Schrader, Melissa Hall, and Nichole Schrader; (second row) Ashley Schrader, Thelma Hay (longtime North Liberty schoolteacher), and Carter Schrader; (third row) Cecil Hay, Hazel Hay, Albert Schrader, and Larry Hay (seated). (Courtesy of Ashley and Diane Whitmer Schrader.)

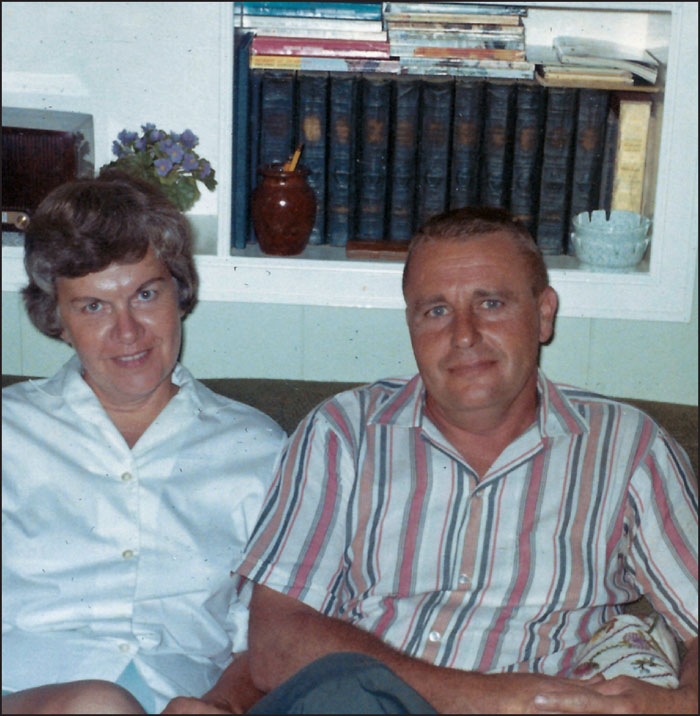

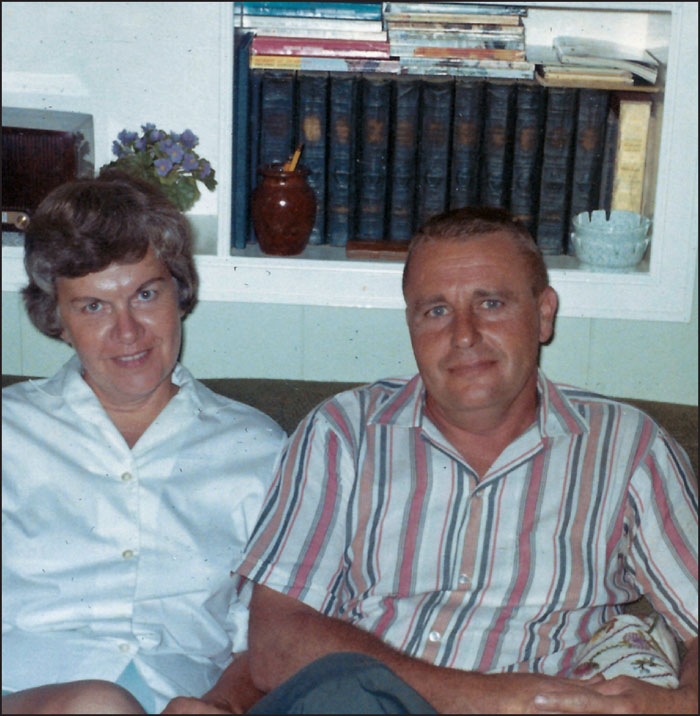

In the 1950s, John Summers, pictured here with his wife, Opal (Moon) Summers, purchased a 76-acre property on Pine Road, just north of State Road 4, from the Moon family. A man-made pond, known as Summer’s Pond, was dug in the early 1960s. It was a popular recreational spot decades before people enjoyed such activities at Potato Creek State Park. (Courtesy of Colby Summers Annis.)

This colorful waterwheel was one of the structures John Summers built for the tranquil retreat. In this photograph, his daughter Colby swims near the waterwheel in the late 1960s; she fondly recalls, “I had a blessed childhood playground.” (Courtesy of Colby Summers Annis.)

The Indiana Department of Natural Resources began demolishing properties sometime in the early 1970s, before the state had acquired the total amount of land necessary for the park. One such property is pictured here. When the first buildings began to be cleared, 2,665 acres of the eventual 3,840 had already been purchased by the state. (Courtesy of Potato Creek State Park.)

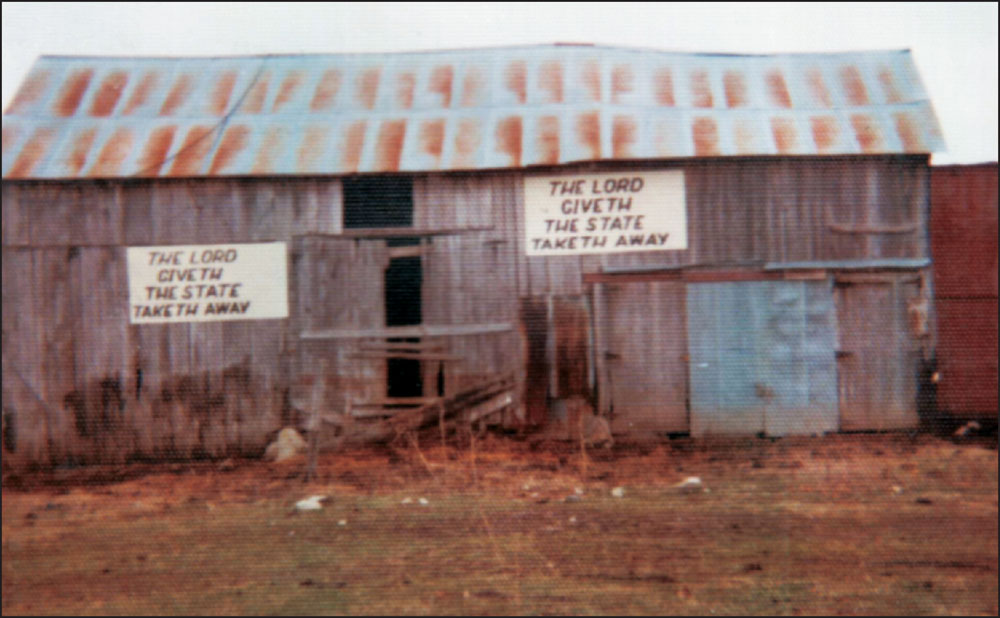

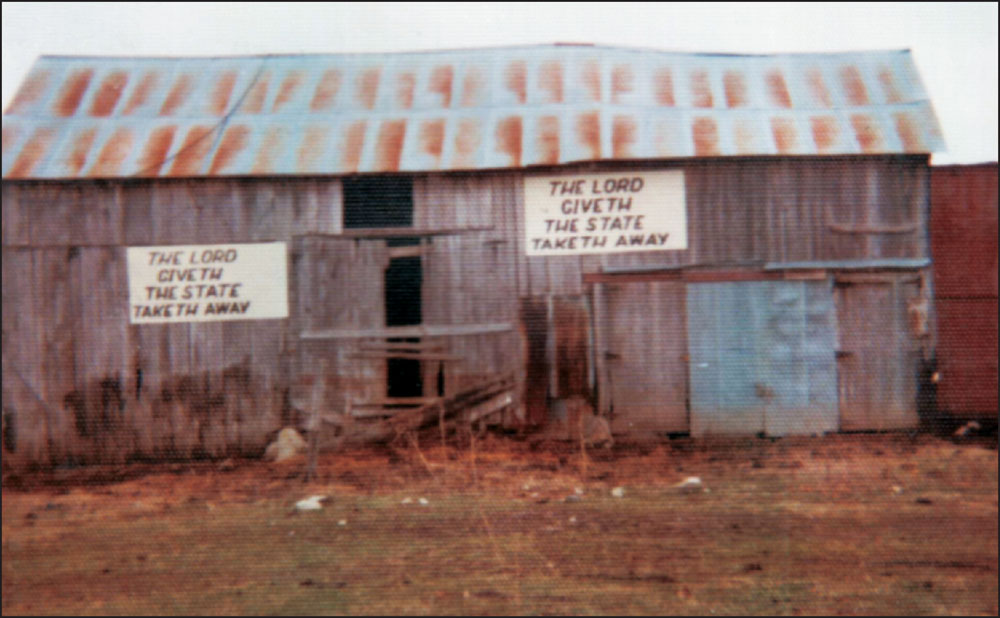

Many early sellers were in support of the state’s buyout; others fought to the very end. Some landowners took the State of Indiana to court and eventually won judgments and received more money for their land than what the state first offered. A few left final messages, such as those on this abandoned barn, on their property before being evicted. (Courtesy of Potato Creek State Park.)

After the state of Indiana owned houses on park property, they sold them at a salvage price. Carol (Howell) Taylor bought the former Star Church parsonage for $850 while her husband, Larry Taylor, was stationed in Vietnam. Some homes, such as the Taylors’ (pictured here in October 1972), were relocated outside of the park area. The former Star Church is visible at right. (Courtesy of Carol Howell Taylor.)

The demolition of former homes, some that had been in families for generations, was often emotional work for those charged with tearing them down. The Howard and Rachel Fullmer home, shown here, met its end by way of a bulldozer. (Photograph by Tim Garbacz; courtesy of Potato Creek State Park.)

Potato Creek State Park was dedicated on June 6, 1977, an unseasonably cool day. Addressing the crowd in front of the newly constructed beach house, Gov. Otis R. Bowen said, “Potato Creek is particularly significant because it brings a major recreational facility to a region of the state which has badly needed additional recreational opportunities.” (Courtesy of Kathie Nelson Sheneman.)

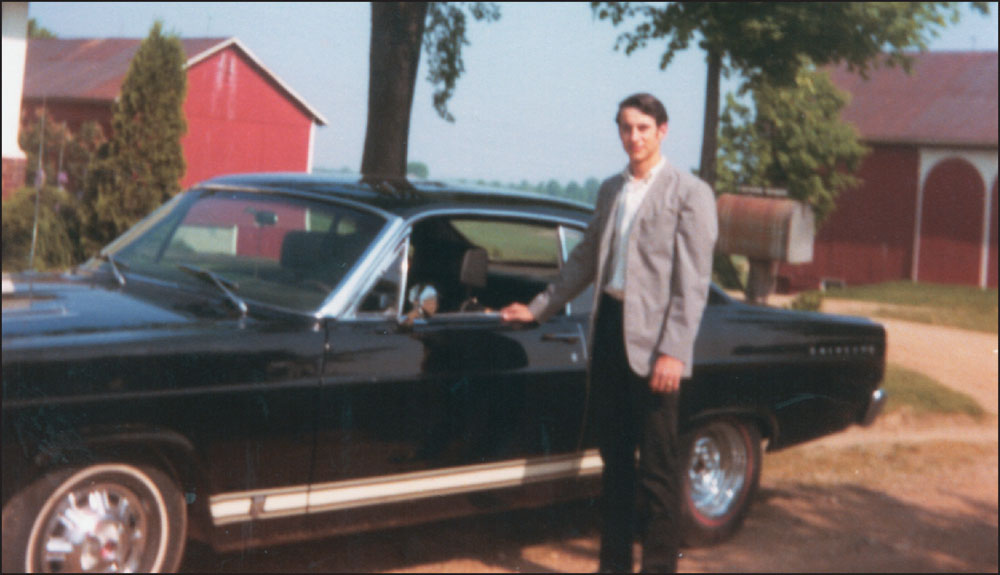

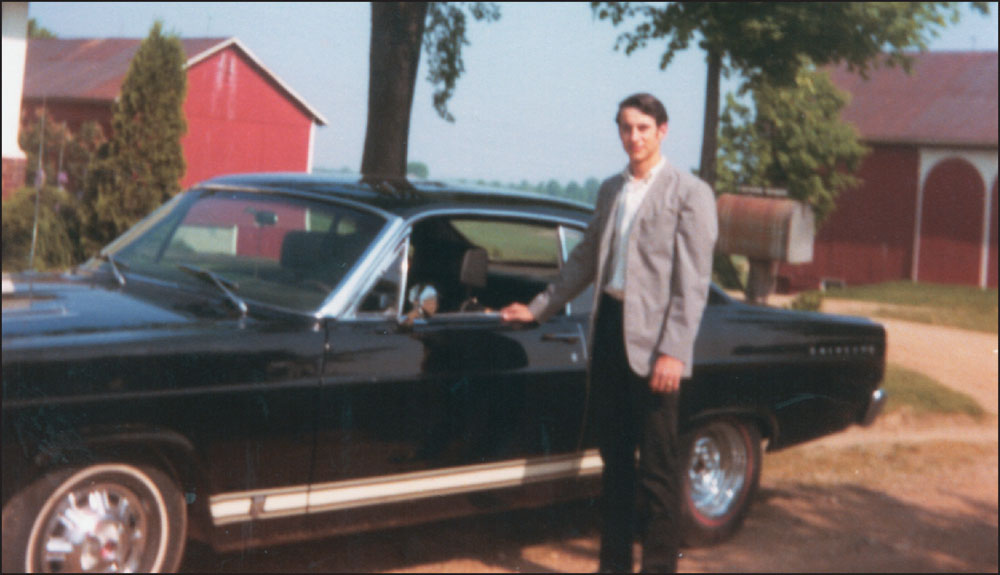

Ken Naragon, son of Raymond and Dorothy Naragon, grew up on the Naragon family farm before working at Potato Creek State Park for nearly 40 years. The field to the left of the barn is part of the former farmland that was flooded to create the lake at the center of the park. (Courtesy of Esther Naragon Shoue.)

Brothers Cleo (left) and Claude Sheneman, pictured here in the early 1970s, both worked at the park during its transformation from farmland to parkland. Cleo, a handyman, was one of the only individuals who lived inside the park during the time after the final properties had been acquired. Claude painted signs and was a groundsman for the land he once called home. (Courtesy of Gladys Sheneman.)

Porter Rea is a public cemetery located inside Potato Creek State Park. Some feared that the damming of the creek would wash away the graves, but the state took precautions, and the tranquil cemetery remains open to this day. Many former park residents, landowners, and local pioneers were laid to rest at the cemetery, which is pictured below in the summer of 2014. (Photograph by the author.)

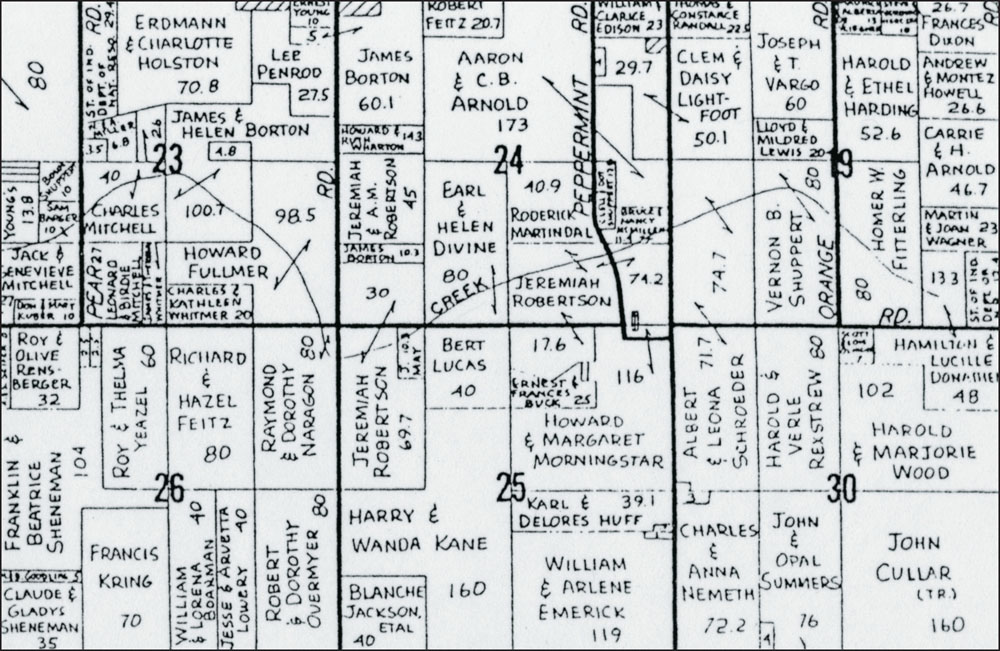

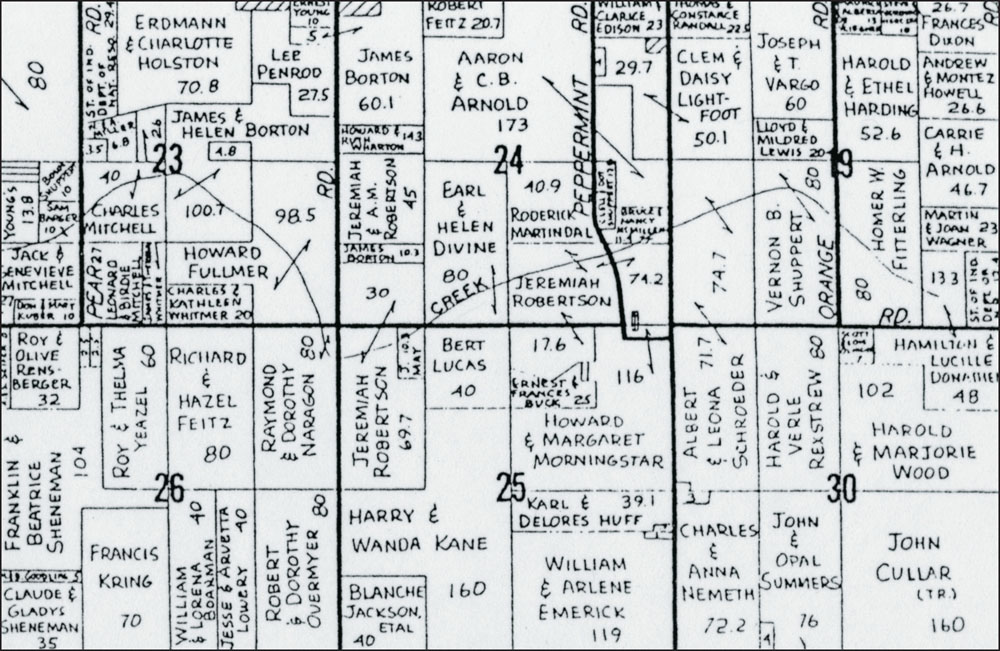

This 1970 plat map of Liberty Township shows the landowners of the 3,840 acres that would eventually become Potato Creek State Park. The park is bordered by New Road to the north, State Road 4 (previously Pierce Road) to the south, Redwood Road to the west, and Oak Road to the east. The numbers next to the names indicate the amount of acres each person or family owned. (Courtesy of Potato Creek State Park.)

This composite image shows the 1970 plat map pictured on the previous page superimposed over a 2011 aerial photograph of the park. The 350-acre man-made reservoir in the center is the main attraction at Potato Creek State Park. (Courtesy of Timothy Cordell.)

For more than three decades, self-taught naturalist Darcey Worster dreamed of a park that would include a man-made lake. Worster “bugged” politicians about this idea by creating insects made of acorns and hickory nuts (pictured above with Worster) and sending them to local and state representatives. Worster did not get to see his lifelong dream become a reality; he passed away on November 11, 1974. His obituary called him the “Father of Potato Creek.” At the park’s dedication ceremony, Gov. Otis R. Bowen announced that the reservoir would be named Worster Lake as a tribute to the man whose passion is still remembered. The lake, pictured below in 2014, provides fishermen with a plentiful stock of bass, bluegill, crappie, channel catfish, and brown trout. (Above, courtesy of Potato Creek State Park; below, photograph by the author.)