7

A PEOPLE’S REVOLUTION

July–August 1789

ON JUNE 17, 1789, WHEN THE THIRD ESTATE DEPUTIES IN VERSAILLES PROCLAIMED themselves the National Assembly, they set a revolution in motion. Despite the radical nature of their actions, however, they had hoped that their movement would succeed without violence. When the king commanded the deputies from the privileged orders to join the Assembly on June 27, those hopes seemed to have been fulfilled. Two threats menaced their hopes for a peaceful outcome to their actions. One was the possibility that the king would resort to military force to dismiss them and restore the absolutist regime; the other was that popular unrest, spurred by the high price of bread combined with fears for liberty, would boil over into uncontrollable violence that would threaten the very foundations of society.

On the night of July 11, both of the deputies’ fears were realized. In Versailles, Louis XVI dismissed his chief minister. At the same time, even before the news of Necker’s dismissal had arrived, the population in Paris turned to violence, attacking and burning several of the toll gates, or barrières, that surrounded the city, where taxes were levied on the food and drink the common people bought every day. Like the king, the people of Paris were ready for a showdown. Using the force of their numbers, they would either make the government take action to meet their demands or else resort to violence to repress them. By the evening of July 14, just three days later, the movement that had begun when the deputies of the Third Estate named themselves the National Assembly was transformed from a revolution of words into a revolution of deeds, and from a movement led by a small elite into a movement of the common people.

Revolutionaries though they were, and focused as they were on the danger from the king and his troops, the deputies were also deeply concerned about the danger of the kind of popular violence the assaults on the Paris toll gates exemplified. As property-owners themselves in a society where the majority of the population lived in poverty, they knew this fear was warranted: the people might undermine the stability of the “common laws” that Sieyès had called the very basis of the nation. Even before the crisis that exploded on July 11, the deputies were aware of the potential contradiction between their desire for a social order based on laws and the popular demand for immediate actions to improve their lives. The letters many of them received from their home districts, telling them of violent disturbances sparked by bread prices and unemployment, were a constant reminder that the population faced problems that were more immediate than the making of a new national constitution. Mirabeau warned that “it is too easy to get [the people] to abandon the constitution for bread.”1

The contradiction between respect for the law and demands for action had already surfaced in the first important speech given by the deputy Bertrand Barère, a future member of the Committee of Public Safety, which would govern France during the most radical phase of the Revolution. The speech was on June 19, just two days after the proclamation of the National Assembly. On the one hand, Barère acknowledged, the high price of bread was reducing the people to eat “food that is unfit for consumption, unhealthy and insufficient”; on the other hand, the emergency bans on the circulation of grain, meant to keep supplies from being shipped out of areas in need, violated the legal “rights of citizens and landowners” to do as they pleased with their property. Convinced, as a good disciple of the economic theorists of the eighteenth century, that the fertile soil of France must be producing enough food for its population, Barère concluded that the food shortage could only be the result of “the disastrous projects of enemies of the people, enemies of humanity,” who needed to be “discovered, intimidated and punished.”2 Speeches like Barère’s contributed to fears of conspiracies that helped incite direct popular action.

The reaction to Necker’s sudden ouster and the riots at the toll barriers brought together two powerful currents of popular unrest: fear of a royal coup d’état against the National Assembly, and the demand for immediate relief from hunger. By midday on July 12, the news had spread throughout Paris. A crowd gathered at the Palais-Royal, whose arcades, cafés, and shops made it a forum for public opinion. As the news of Necker’s dismissal and the violence at the toll barriers flooded in, public opinion turned into public action. In the central garden, groups gathered around impromptu orators. The young lawyer Camille Desmoulins, who had spent the previous few weeks feverishly rushing between Paris and Versailles to keep up with events, climbed up on a table to make himself better heard. He cried, “Citizens, you know that the Nation wanted Necker to be kept in office; he’s been chased out! Could anyone insult you with more insolence? After this, there’s no telling how far they will go.” He ended his oration with a ringing call: “To arms! To arms!”3

Around noon, a crowd of several thousand headed into the streets around the Palais-Royal. To show their unity, the demonstrators plucked leaves from the trees in the garden of the Palais-Royal and put them on their hats. The marchers’ first action was to demand that the theaters in the neighborhood cancel performances. As the crowd passed the door of another of Paris’s attractions, Philippe Curtius’s wax museum, where lifelike figures of leading public figures were exhibited, demonstrators stopped to take its busts of Necker and the duc d’Orléans. The latter was seen by some as a possible replacement for his stubborn cousin Louis XVI. The two men’s effigies announced a political program: a government headed by men supported by the people.

By 5:00 p.m., the agitated crowd had reached the Place Louis XV, the great square at the western end of the Tuileries Gardens now known as the Place de la Concorde. The gardens themselves were filled with Parisians, many of them members of the city’s more prosperous classes: unlike the Palais-Royal, with its prostitutes, the Tuileries was considered safe ground for families and women concerned about their reputation. On this day, however, soldiers and cavalrymen from the regiments recently brought to Paris on the king’s orders were assembled at the square. They were ordered to stand their ground as the angry crowd jeered and threw rocks at them. Among those who passed by during this standoff was Thomas Jefferson, the American ambassador to France. Having helped start one revolution, he now became an eyewitness to the beginning of another.

After several hours, the troop commander, the baron de Besenval, tried to stop the disorder by ordering his cavalrymen to force the crowd back into the Tuileries. It was a disastrous mistake: the troops’ action gave substance to the rumors that the army was about to be turned loose on the Parisians, even those from the middle classes. The cavalrymen who penetrated into the Tuileries were driven back when the crowd pelted them with heavy stones taken from a nearby construction site. Besenval reported to his superior, the duc de Broglie, that—as Broglie had feared even before the crisis erupted—it would be impossible to restore order in Paris by military force. Besenval then withdrew his soldiers: they would play no role in the events of the next two days. As the real threat from the army diminished, however, the population’s fear of an attack worsened. From every part of the city, rumor reported imaginary columns in uniform, ready to massacre civilians.

With the forces of order paralyzed, disturbances continued to spread in Paris during the night of the 12th; by morning, forty of the fifty-four customs barriers around the city had been destroyed. Inside the city, improvised groups organized to maintain order. In the neighborhood around the Palais-Royal, the pamphleteer Brissot helped organize volunteers to guard the royal treasury and the stock exchange.4 Abandoned by the government and the army, an uneasy coalition of royal officials (led by Jacques de Flesselles, the prévot de marchands, a position equivalent to the mayor of Paris) and members of the assembly of electors (chosen the previous April to select deputies to the Estates General) tried to keep control of the city. At dawn, they ordered the churches in the city to sound the tocsin, a monotonous tolling of the steeple bells that served as a warning for emergencies. The purpose was to summon members of the electoral assembly to a meeting at the Hôtel de Ville, the seat of the city government, but the sound of the bells brought the entire population out in the streets. Early in the morning, rioters stormed and pillaged the convent of Saint-Lazare. The large quantities of flour and wine they found—stocks that the monks had accumulated so they could carry out their mission of providing charity to the poor—gave substance to accusations that privileged groups were hoarding food in order to drive up prices.

Expecting a military attack at any minute, the crowd demanded weapons. Throughout the day of the 13th, huge throngs gathered at the Hôtel de Ville and even forced their way into the building in search of guns and powder. They confiscated some obsolete museum pieces, including halberds and crossbows, from a royal warehouse, but these were hardly adequate to stand up to a modern army. In the afternoon, a crowd converged on the Invalides, the complex built by France’s most celebrated king, Louis XIV, to house retired veterans, but its commander succeeded in keeping them away from its stocks of arms. (The complex now contains the tomb of Napoleon Bonaparte, the man who would later end the Revolution.) At the Hôtel de Ville, Flesselles repeatedly sent groups on what proved to be fruitless searches for arms in other parts of the city. Rumors spread that he was deliberately deceiving the people, trying to buy time until the army intervened.

While Flesselles was trying to cope with the crowd outside the Hôtel de Ville, an emergency committee of members of the electoral assembly was rapidly taking over his powers. Throughout the day, “news of disasters kept arriving with great rapidity,” the assembly’s official minutes noted.5 Acting on their own, groups in different parts of the capital arrested and sometimes hanged suspects they branded as troublemakers. The Place de Grève, the large square in front of the Hôtel de Ville, became cluttered with coaches and wagons seized by vigilantes, who insisted that they belonged to conspirators trying to smuggle arms and valuables out of the city.

Many of the electors and city officials surely remembered that just a few years earlier, in 1780, rioting crowds in the British capital, London, had burned and looted much of the city during the so-called Gordon riots, causing immense property damage. How were they to defend the cause of liberty without unleashing the forces of anarchy? The emergency committee decided to form a “bourgeois guard” composed of respectable citizens to replace the royal troops, whom the population no longer trusted, and the spontaneous groups that were springing up in the streets. As the radical Breton deputy Jean Le Chapelier put it in supporting the decision, “it is the people who should protect the people.”6 So that the guardsmen could be identified, they were told to pin a red and blue cockade, a piece of ribbon in the colors of the coat of arms of the city of Paris, to their hats or jackets. This cockade quickly replaced the green leaves the crowd had adopted the previous day as the symbol of the patriotic movement. Although the formation of the National Guard was less dramatic than the following day’s assault on the Bastille, it was equally significant. The revolutionary movement now had an armed force of its own, one that thousands of citizens would join in the years to come. Control of the National Guard would be crucial in the power struggles that determined the course of the Revolution.

As dawn broke on Tuesday, the 14th of July, women in Paris went out to perform the daily chore of buying bread for their families at local bakeries. They returned home irate: the price of the loaves that were the basis of the ordinary Parisian’s diet had spiked to the highest point in decades. No wonder one of the first chroniclers of the day’s events reported that “women made their husbands go out and urged them on, telling them, ‘Get going, coward, get going; it’s for the king and the country.’”7 Early in the morning, a crowd larger than any of those on the previous days surrounded the Invalides on Paris’s Left Bank. This time, they were determined to seize the thousands of muskets its commander had refused to distribute the day before. The crowd might have been dispersed by Besenval’s five thousand regular soldiers, who remained camped a few hundred yards away on the Champ de Mars, but they did not stir. Their officers feared that the men would not fire on the people, and that they might even join them.

Eventually members of the crowd pushed their way into the Invalides. The veteran soldiers refused to fire on the intruders; the crush in the building’s basement, where arms were stockpiled, was so bad that people were trampled and nearly suffocated. The watchmaker Jean-Baptiste Humbert, one of those who would soon distinguish himself in the fighting at the Bastille, found that the only way he could get out of the building was to “force a way through the unarmed crowd… by threatening to bayonet them in the gut.”8 The guns they seized were passed out freely, with no attempt to restrict them to the respectable bourgeois citizens who were supposed to form the new civic guard. The arsenal contained no cartridges or gunpowder, however. If the Parisians were going to be prepared to mount an effective defense against a possible attack by the army, they needed to get their hands on the barrels of powder stored in the Bastille.

Located in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, a working-class neighborhood on the eastern side of the city, the Bastille, with its crenellated towers, was a genuine relic of the Middle Ages and a powerful symbol of royal authority. In 1782, when he published a lurid account of his captivity in the Bastille, the dissident writer Simon-Henri-Nicolas Linguet illustrated his story with a striking engraving: it showed a lightning bolt toppling the Bastille’s towers while grateful subjects knelt before a statue of Louis XVI in front of the fortress. The message was clear, and also prophetic: if the French were to be free, the Bastille had to be destroyed. Now the moment had come to translate Linguet’s image into action.

The Bastille’s commander, the marquis Bernard-René Jourdan Delaunay, was aware of the dangers surrounding him and had been preparing for more than a week. Residents of the neighborhood had been able to watch as the gunports in the fortress’s towers were enlarged to give its cannon a clearer field of fire, and cartloads of heavy paving stones were carried up to the top of the fortifications so they could be thrown down on assailants. As a crowd began to gather around the Bastille in midmorning on July 14, Delaunay initially seemed ready to negotiate. He met with several delegates from the municipal committee at the Hôtel de Ville, and even invited some of them to share his breakfast. Delaunay promised that he had no intention of opening fire, but he drew the line at allowing members of the newly formed civic guard to join his troops inside the fortress’s walls, and he refused to open its gates to the angry crowd outside.

The crowd swarming around the Bastille came from a very different social universe than the prosperous, educated electors who were trying to maintain a minimum of order at the Hôtel de Ville. Opponents of the Revolution denounced them as a “rabble” drawn from the lowest orders of the city’s population, but in fact the majority of them were established residents of the Saint-Antoine neighborhood with regular occupations. In June 1790, 954 individuals—953 men and 1 woman, the laundress Marie Charpentier—were officially recognized as “conquerors of the Bastille.” Of the 661 whose professions were listed, the majority were skilled craftsmen—men like the glazier Jacques Ménétra, self-confident and experienced at carrying out collective actions to assert their interests. Alongside the residents of the faubourg on July 14 fought soldiers from the Gardes françaises and deserters from some of the other regiments brought to the city. Perhaps a sixth of the “conquerors” came from the middle class or bourgeoisie, such as the brewery owner Antoine-Joseph Santerre, who would go on to become a major figure in Parisian revolutionary politics. The oldest of the “conquerors” was a man of seventy-two, the youngest a boy of eight.

At around 1:30 in the afternoon, a loud explosion from the Bastille announced the catastrophe the whole city had dreaded for the past three days: the troops in the fortress had opened fire on the crowd. In the confusion at the scene, no one could say who fired the first shot. Members of the crowd had succeeded in forcing their way past the Bastille’s outer gate and had lowered a drawbridge that gave access to the inner courtyard. There, they faced the heavily defended entry to the central fortifications and were easy targets for the soldiers posted above them. The sequence of events convinced the attackers that Delaunay had deliberately lured them into the courtyard so they could be mown down by fire from the towers. As cries of “treason!” filled the air, the fighting became more intense. Without artillery, however, the assailants could not blast their way past the main door of the fortress, and the parapets of the towers protected the soldiers from rifle fire. Only one of the soldiers would be killed during the fighting.

Back at the Hôtel de Ville, the municipal committee was at a loss for ideas. Two electors were dispatched to Versailles to alert the deputies of the National Assembly and beg it to take measures to “spare the city of Paris the horrors of civil war.” The committee knew, however, that any assistance from that quarter would come too late to affect the course of events. While the committee members dithered, Pierre-Augustin Hulin stepped into action. Hulin, one of the orators who had launched the popular movement at the Palais-Royal on July 12, found two companies of soldiers from the Gardes françaises assembled in front of the Hôtel de Ville and began haranguing them. “Don’t you hear the cannon… with which the criminal Delaunay is assassinating our fathers, our wives, our children?” he demanded. “Will you let them be slaughtered?”9

With Hulin in the lead, the soldiers headed for the Bastille, bringing with them two small cannon taken from the Invalides earlier in the day. They reached the fortress around 3:30 p.m., about two hours after the start of the fighting. There, they joined another group of soldiers, led by an army lieutenant named Élie, and brought their cannon into position for a systematic assault on the Bastille’s fortified gate. Inside the fortress, Delaunay realized he could not hold out very long. For a moment, he threatened to detonate the 250 barrels of gunpowder stored in the fortress rather than surrender. Such a gigantic explosion would have destroyed not only the Bastille but the neighborhood around it. His own soldiers stopped him from acting on this impulse and refused to go on firing. When the crowd rejected any terms other than unconditional surrender, Delaunay and his soldiers yielded and lowered a small drawbridge next to the main gate. “The people then showed an unheard-of resolution,” one eyewitness reported. “They threw themselves into the moat of the Bastille, used the shoulders of the stronger ones as ladders, climbed on each other’s backs. A dozen of the most vigorous, armed with axes, broke the gate… two thousand people rushed in, and soon a white flag announced that the Bastille was ours.”10

The victorious crowd swept through the building, grabbing the weapons the defenders had abandoned and tossing archival documents out the windows. The attackers had expected to find numerous prisoners and were surprised to find only seven, most of them victims of mental illness being held at their families’ request. They were set free and triumphantly paraded through the streets, although at least one of the deranged men had to be incarcerated in another institution the following day. It took several days before the victors convinced themselves that there were no other inmates hidden in secret cells.

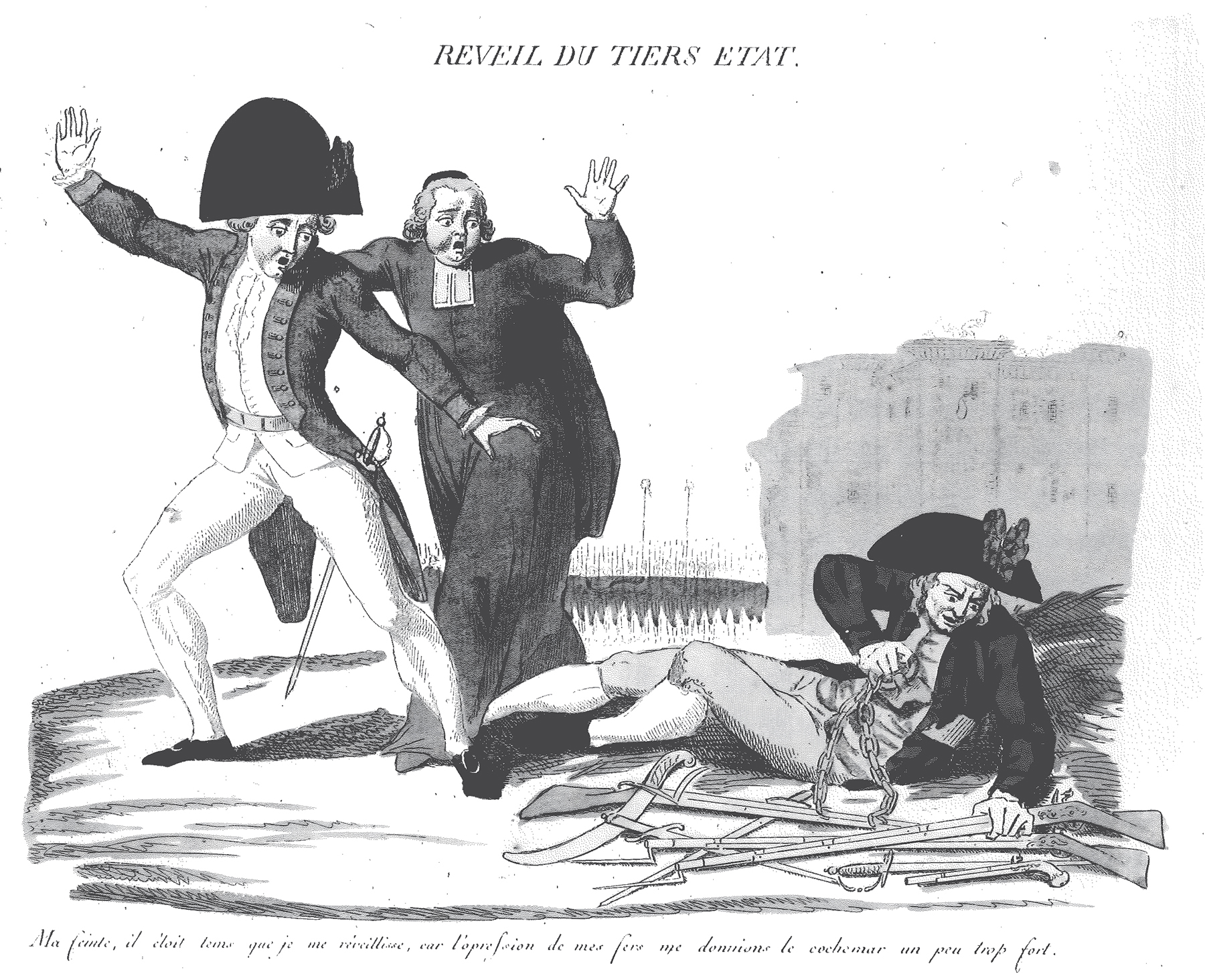

AWAKENING OF THE THIRD ESTATE: Figures representing the nobility and the clergy recoil in alarm as a commoner from the Third Estate breaks his chains and prepares to take up arms. In the background, a crowd carries the heads of the Bastille’s commander, the marquis Delaunay, and Jacques de Flesselles, who led the city government. Easily understood images like this conveyed the meaning of the events of 1789 even to those who could not read. Source: Library of Congress.

The passions stirred up during the fighting doomed the Bastille’s commander and several of his officers. Convinced that Delaunay had deliberately lured the attackers into the Bastille’s outer courtyard in order to massacre them, the crowd dragged him and the other captured officers through the streets back to the Hôtel de Ville. Hulin, who had led the Gardes françaises soldiers who intervened, tried to protect Delaunay so that he could be turned over to the municipal authorities, but as they reached the building, he was overwhelmed. Struggling to protect himself, Delaunay kicked one of the men surrounding him, an unemployed cook named Desnot, in what Desnot delicately called “the parts.” As the cook cried out in pain, other members of the crowd stabbed Delaunay with their bayonets. After Delaunay had fallen, the attackers gave Desnot the honor of decapitating him and putting his head on a pike, crying out that “the Nation demands his head to show to the public.”11

The unfortunate Delaunay soon had company. Inside the Hôtel de Ville, the hundreds of ordinary citizens who had invaded the building demanded punishment for Flesselles, whom they accused of sending them on futile chases for gunpowder in order to buy time for troops who might come to the rescue of the Bastille’s defenders. Flesselles consented to go to the Palais-Royal for an impromptu trial, but he never made it. At the Place de Grève in front of the Hôtel de Ville, a young man put a bullet through his head. Flesselles’s head was also mounted on a pike, and the crowd paraded their two bloody trophies through the streets. The killings of Delaunay and Flesselles and the spectacle of heads on pikes were mentioned in almost every one of the dozens of accounts of the day’s events: no one could ignore the violence woven into the Revolution from its start.

While some members of the crowd were wreaking vengeance on Delaunay and Flesselles, others were turning the day’s events into a story of the triumph of liberty. The playwright Louis-Abel Beffroy de Reigny rushed to the scene to take down testimony from Hulin and several members of the Gardes françaises. He then composed a pamphlet with a long title: “Accurate Summary of the Taking of the Bastille, written in the presence of the main participants who played a role in the expedition, which was read that very day at the Hôtel de Ville.” At the site of the fortress, Pierre-François Palloy, a wealthy building contractor who had joined his workers in the assault, immediately began organizing its demolition. In the following days, he led tours of the cells; eventually he had stones from its walls carved into miniature models of the Bastille, which he dubbed “relics of freedom.” He sent them to provincial cities, where they were received with great ceremony and put on display, so that all French citizens could feel they had taken part in the epic struggle for freedom.12

As darkness fell, the clouds that had covered the sky for most of the long summer day of July 14 turned to heavy rain. Exhausted after seventy-two hours of anxiety and agitation, many Parisians were no doubt relieved by the respite. The thunderbolt of revolutionary action that Linguet had predicted in 1782 had struck the Bastille. Only “legislators and enlightened spirits” had understood the profound significance of the creation of the National Assembly a month earlier, wrote Bailly, who now took Flesselles’s place as mayor of Paris, but “the Bastille, taken and razed, spoke to the whole world.”13

What the violence that swept Paris on July 13 and 14 portended was at first far from clear to the deputies of the National Assembly in Versailles. On the morning of the 13th, as the tocsin sounded throughout Paris, the deputies were trying to grapple with the consequences of Necker’s dismissal, and with the appointment of a ministry bent on restoring the king’s power that had been announced the previous day. The Assembly declared itself in permanent emergency session, but Mounier opened the discussion on the 13th by urging his colleagues to continue their work on the constitution. Any chance that the Assembly could stay focused on that subject disappeared when a deputy who had been in Paris arrived and reported that the city was “in a terrifying fermentation.” As further dispatches came in, the anxiety of the deputies mounted. Several nobles who had previously been reluctant to embrace their new role in the combined assembly rose to exclaim that it was time to put aside all divisions and “unite to save the country.” The Assembly sent a delegation to meet with the king and urge him to withdraw the troops he had sent into the capital. Louis’s response was anything but reassuring. He stood by “the measures that the disorders in Paris have forced me to take” and insisted he was “the sole judge of what is necessary.”14

The day of July 14 was even more nerve-racking. The deputies tried again to focus on constitution-making. They managed to appoint an eight-man committee to draft a declaration of rights, and the abbé Grégoire, the parish priest from Lorraine who was already emerging as one of the most forceful advocates of radical change, strove to assure his colleagues that “it will be in vain if rivers of blood flow, the Revolution will still succeed.” As evening fell, however, the vicomte de Noailles hurried in and told the deputies about the citywide insurrection, the seizure of arms at the Invalides, the capture of the Bastille, and the death of Delaunay. “This news produced the saddest impression on the Assembly. All discussion ceased,” wrote one journalist.15 The Assembly sent a delegation to beg the king to recall the troops whose presence had incited the Parisians to resistance, but the king, not yet willing to yield, gave them an equivocal answer.

Anxious deputies remained in their meeting hall all night, in case emergency action was needed. All morning on July 15, the deputies waited for further reports from Paris and for a sign of the king’s intentions. Meanwhile, the king, who had entered a single word, “Rien” (Nothing), in his private journal under the date of July 14, indicating that he had not gone hunting, absorbed the significance of the fact that his soldiers “would not fight against their fellow citizens,” as the duc de Broglie put it. Finally, Louis XVI decided to address the National Assembly personally. Accompanied by his brothers, the counts of Provence and Artois, he announced that he had ordered the withdrawal of the troops from Paris. For the first time, he referred to the body by the title it had given itself, “National Assembly,” instead of calling it the Estates General, and he asked the deputies to send a delegation to Paris to calm the fears of the population.16

The deputies were overwhelmed as they heard the king promise to work with them to end the crisis without mass bloodshed. The marquis de Ferrières tore open an already sealed letter to his wife to add to it, telling her how a crowd “drunk with joy” had surrounded the king and his two brothers as they returned to the palace after the king’s speech and then cheered as the royal family appeared on the balcony. The delegation of deputies sent to Paris were welcomed with wild celebrations. In his memoirs, Bailly remembered “acclamations and expressions of joy… tears, cries of ‘Long live the Nation! Long live the king! Long live the deputies!’ They were given red, blue and white cockades; people surrounded them and embraced them.”17 The addition of a white stripe to the red and blue cockades improvised on the previous day was a gesture of reconciliation between the monarch and the people: white was the symbolic color of the Bourbon dynasty, which was now combined with the colors of Paris. The cockades, manufactured in silk for the well-to-do and cheaper woolen versions for the poor, became the first of a flood of symbolic objects, such as pottery decorated with patriotic motifs, that advertised their purchasers’ support for the revolutionary cause.

The tumultuous welcome they received in Paris on the 15th convinced the deputies that, rather than threatening the social order, the city’s population supported their efforts to remake the country. Their confidence in the people’s support stiffened the deputies’ resolve to compel the king to dismiss the Breteuil ministry and recall Necker. “The prayers of the people are orders,” the marquis de Lally-Tollendal, a liberal noble, said during debates on the 16th. At a meeting of the royal council that morning, Louis XVI conceded not only that there was no further possibility of using military force to restore his authority, but that he could not resist the demand for Necker’s return, even though it meant accepting the principle that government policies would now be set by the Assembly rather than by the monarch. The comte d’Artois and several court figures closely tied to Marie-Antoinette, including her favorite, the duchess of Polignac, hurriedly packed their bags and fled the country. They were the first of what would become a stream of counterrevolutionary émigrés seeking refuge abroad.

If he was to retain any power at all, Louis XVI had to convince the deputies and the population of the capital that he was prepared to accept his new status as a constitutional monarch with limited powers. With grave forebodings, the king prepared on July 17 to venture into the middle of the city that had driven out his soldiers just three days before. Escorted by a delegation of Assembly members and a huge crowd, he was greeted at the gates of the city by the newly installed mayor, Bailly, who announced that “the people has reconquered its king.” As the procession crossed the city to the Hôtel de Ville, the Austrian ambassador, Mercy d’Argenteau, noted that there were few cries of “Long live the king!” but many shouts of “Long live the Nation!” At the Hôtel de Ville, Bailly handed the king a tricolor cockade, and the king stuck it on his hat. Awkward as always when he had to speak in public, Louis XVI managed to assure the crowd that “you can always count on my love,” and he was cheered when he appeared on the balcony of the Hôtel de Ville with his cockade. The Portuguese ambassador could hardly believe that he had seen “a king of France in a rustic carriage, surrounded by bayonets and the muskets of an immense crowd of people, and finally obliged to wear on his hat the cockade of liberty.” More enthusiastically, Thomas Jefferson called it “an apology such as no sovereign had ever made, or any people ever received.”18

At ten o’clock that night, Louis XVI finally reached the palace of Versailles, where Marie-Antoinette had been anxiously waiting for him, concerned for his safety. We do not know his innermost thoughts about the extraordinary events the country had just witnessed: seven days that had begun with his attempt to reassert his authority by dismissing Necker, and had ended with the emotional scene of reconciliation at the Hôtel de Ville. As he had been taught in childhood, the king kept his secrets to himself.

The deputies were more voluble. As they realized that the troops that had been menacing them were being sent away, and that the conciliatory minister Necker was being recalled, they hastened to frame the story of the crisis in reassuring and even inspiring terms for their correspondents. A Third Estate deputy, Jean-Antoine Huguet, put it this way:

It is unique, in the annals of the universe, to see a people, in just five days, arm itself in the greatest order, use force to procure the necessary arms, take and destroy a fortress, the bulwark of despotism; to see, on the fifth day of the Revolution, the ruler whom these hostile actions seemed to threaten, come put on, in the midst of this people in revolt, the cockade that they had taken to obtain liberty for themselves; to see this same ruler receive from this same people the most touching signs of love and fidelity. It was reserved for the French nation to give this example to the universe.19

Like most of the deputies, Huguet chose to emphasize the magnitude of the threat the people had faced, the courage with which it had responded, and the reconciliation between king and people with which the crisis had ended. In Paris and Versailles, few dared to describe the events in any other terms. From the safety of the Dutch city of Leiden, the editor of the continent’s most respected newspaper used more critical language. In the Gazette de Leyde, the crowd in Paris was described as “a vile populace, which, in giving itself over to pillage and to the most awful excess, spread terror and panic everywhere” until it was successfully contained by the armed bourgeoisie. The storming of the Bastille merited only a half-sentence in this report and was overshadowed by the killings of Delaunay and Flesselles. Nevertheless, the paper could not help applauding the final triumph of the National Assembly and the end of the last resistance from the privileged orders. “It is thus that good comes out of the most extreme evils,” the account concluded.20

Whether they regarded it as a triumph of freedom or a breakdown of order, everyone who experienced the crisis recognized that they had just lived through an exceptional event. Europe’s most powerful monarch had been forced to bow to the people and to the authority of an elected assembly. The representatives of the French nobility and the established Catholic Church had abandoned their claims to political privilege and agreed to join in the making of a new society based on the principles of equality and individual liberty. The American Revolution had been carried out by a “new” people on the fringes of the Western world, far from the center of European civilization. With the storming of the Bastille, a revolution was now unfolding at that civilization’s very heart. Its consequences would affect not only the twenty-eight million people of France and its colonies, but the entire world.