12

A SECOND REVOLUTION

October 1791–August 1792

ON OCTOBER 1, 1791, THE DAY AFTER THE FINAL SESSION OF THE NATIONAL Assembly, the 745 members of the first legislature to be elected under the new constitution took their predecessors’ places in the Manège, the riding hall that had been converted into a parliamentary meeting place two years earlier. Whereas half of the legislators in the National Assembly had originally been elected as representatives of the old regime’s privileged orders, the clergy and the nobility, the overwhelming majority of the new legislature’s members had been part of the Third Estate before the Revolution. Under the rules passed in 1789, they had to be wealthy enough to pay the equivalent of a marc d’argent in taxes, which distanced them from the urban populace of Paris and from the peasantry who made up the vast majority of the French population. Thanks to Robespierre’s “self-denying ordinance,” none of the new deputies had been members of the previous assembly. The new deputies were supporters of the Revolution: two-thirds of them had held local office since the start of the movement. Like the members of the National Assembly, they came from all over the country, and few knew many of their new colleagues before they found themselves charged with making the new constitution function.

With diehard members of the nobility having emigrated and clergy who opposed the Civil Constitution ineligible to run, there were no outspoken defenders of the old regime to take the place of the deputies of the National Assembly, such as the abbé Maury, who had regularly denounced the revolutionary experiment. But only a handful of the new legislators, such as Antoine Christophe Merlin de Thionville, Claude Basire, and François Chabot, were associated with the radical Cordeliers Club in Paris, which had called for the replacement of the monarchy by a democratic republic after the king’s flight. Just fifty-two of the new deputies joined the Jacobin Club, which, true to its official name, Friends of the Constitution, hesitated to openly criticize the new constitution that had just gone into effect. Traveling through the countryside on her way to Lyon, Madame Roland wrote to Robespierre, with whom she was still friendly, that the population “raised their hackles at the word of republic, and a king seems to them essential to their existence.” Her letter strengthened his conviction that the supporters of the Revolution should vigilantly defend the document’s provisions and put the onus for violating them on the king. In mid-October 1791, when the firebrand journalist Camille Desmoulins predicted that the new constitution would not last long, because of the glaring contradiction between its “divine preface,” the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, and its other provisions, many Jacobins attacked him for undermining the new institutions.1

The Feuillants, the group of moderates who had broken away from the Jacobins at the time of the massacre of the Champ de Mars in July 1791, initially had more sympathizers among the new deputies. The popularity of the Feuillants reflected a widespread hope that the king would cooperate and help to make the new constitutional monarchy work. Behind the scenes, the former Feuillant leader Barnave kept up his correspondence with Marie-Antoinette, urging her to press the king to make more convincing gestures to show his acceptance of the new regime. Events had turned the giddy princess whose escapades had scandalized Versailles into a calculating political strategist. The queen largely replaced the king in trying to save the monarchy, both from the revolutionaries and from “the follies of the princes and emigrants” whose efforts to promote a foreign invasion of the kingdom put the royal couple’s lives in danger. Marie-Antoinette remained opposed to any genuine cooperation with the Revolution. In one letter to Fersen, she wrote, “There is nothing to be done with this current Assembly, it is a collection of criminals, fools and idiots.”2 Nevertheless, she was convinced that the only chance of defeating the movement was to let its own internal contradictions destroy it.

As it became clear that Louis XVI was not prepared to make genuine compromises with them, the Feuillant club lost its appeal to the deputies. The Jacobins, in contrast, continued to extend their network of provincial affiliates, and the debates at their meetings in Paris, extensively publicized in the press, mobilized public support for their ideas. Robespierre, who had done so much to preserve the Jacobin network after the split with the Feuillants, remained an important presence in the Paris club, even though he was now out of office. The most dominant representative of the movement, however, was the journalist and newly elected deputy Brissot. He found support from a group of deputies from the department of the Gironde, the area around Bordeaux. They included Pierre Vergniaud, a dazzling orator, and his colleagues Élie Guadet and Armand Gensonné. Hostile journalists soon began to speak of “Girondins” or “Brissotins” as an organized faction, although the group had no formal organization or clear program. Attracted by the brilliant and witty Madame Roland, Brissot and many of his allies met regularly at the apartment she and her much older husband occupied. Unlike Olympe de Gouges or Etta Palm d’Aelders, Madame Roland did not speak out on issues of women’s rights, but she was eager to promote the success of the Revolution and energetically encouraged the men in her circle to stand up for its principles.

There was a certain amount of justification for Brissot’s conviction that he deserved to lead the revolutionary movement. His role in founding the Society of the Friends of the Blacks showed a genuine commitment to the ideal of freedom for all men, even when it meant challenging strong vested interests, and in 1789 he had been among the strongest advocates for freedom of the press and the notions of natural rights and national sovereignty. When his sometime associate Mirabeau had embarked on his perilous effort to combine support for the Revolution with advocacy for a strong monarchy, Brissot had retained his deep suspicion of royal power. He had also been quick to turn against the early Jacobin leaders, such as Barnave and Duport, when they began retreating from what he regarded as the essential principles of liberty and equality. Until his election to the Legislative Assembly, Brissot had generally been an ally of Robespierre, although his prerevolutionary experiences, which had included extensive foreign travel and contact with influential political figures, convinced him that he had a more sophisticated knowledge of the world than the earnest provincial lawyer from Arras. Comfortable holding forth in assemblies dominated by middle-class participants or among small groups of friends, such as those who gathered in the Rolands’ apartment, Brissot lacked Danton’s ability to bond easily with the common people of Paris, and his newspaper lacked the populist appeal of the publications attributed to the Père Duchêne or Marat’s Ami du peuple. In the long run, Brissot’s inability to hold the trust of the Jacobin radicals or win over the popular movement would prove fatal to him and his network of allies. But for nearly a year, no one had a greater influence on the direction of the Revolution.

As Brissot and the Jacobins squared off against the more conservative Feuillants, a new word entered the revolutionary vocabulary: sans-culottes, literally, “without breeches.” At first, the epithet was used dismissively by conservatives to stigmatize men from the lower classes who wore long workingmen’s trousers rather than the knee breeches and stockings required in respectable society. Soon, however, left-wing journalists turned the term into a label for true supporters of the people’s cause, particularly those from the lower classes. The most famous answer to the question, “What is a sans-culotte?” defined him as “a being who always goes on foot, who has no millions… and who lives simply on the fourth or fifth story with his wife and children, if he has any. He is useful, because he knows how to plow a field, to work a forge, a saw, a file, to cover a roof, make shoes and give the last drop of his blood for the Republic.”3

THE VOICE OF THE PEOPLE: Two examples of newspapers attributed to the Père Duchêne, written in simple language the common people could understand. On the left, an issue from 1790 shows the Père Duchêne wearing a respectable coat. In the image on the right, from 1791, he wears rough workingman’s clothes. The two pistols in his belt, the hatchet brandished over his head, and the musket in easy reach leave no doubt about his revolutionary militancy. Source: Newberry Library.

In practice, many of those who came to call themselves sans-culottes were wealthier and more educated than this stereotype suggested. To be a sans-culotte was as much a matter of political behavior as of social class. Many of the leaders of the Paris sans-culotte movement were small businessmen like the veteran glassfitter Jacques Ménétra, whose election to numerous positions of responsibility in his Paris section showed the extent of his local connections. Others, like the brewery owner Antoine-Joseph Santerre or the Polish nobleman Claude François Lazowski, won acceptance through their leadership during revolutionary journées. The sans-culotte was the virtuous opposite of the aristocrate, but was also increasingly opposed to the wealthier and more educated stratum of the Third Estate. Radical militants began using the term “sans-culottes” to rally opposition not just to the former nobles, but to all those who refused to identify themselves with the common people.

Although the popularity of the term projected the urban lower classes into the center of political debate, the attitudes of the peasantry would prove equally important in shaping the outcome of the Revolution. Among the many last-minute enactments of the outgoing National Assembly was a rural code that was meant to institutionalize the sweeping changes in laws affecting the lives of villagers, who made up the overwhelming majority of the French population. Legislators in Paris had a mental image of simple country folk whom they could mold into a new “regenerated” citizenry, but they recognized that they could not change the harsh economic realities of rural life. As the editors of the Feuille villageoise, an inexpensive weekly newspaper aimed at a rural audience, wrote, “being unable to bring wealth to the villages, we will at least try to give them truth and instruction.”4 The attitude of many deputies toward the rural population was reflected in the paper, which openly told its readers that they lacked the basic knowledge to understand political debates unless they were presented in the simplest terms.

Peasants may not have followed the intricacies of politics as closely as the Paris sans-culottes, but they had a keen sense of their own interests. The country population was not the uniform mass that the deputies often imagined. Rural communities in the crowded wheat-growing regions of northern France were deeply divided by tensions between their minority of wealthy farm entrepreneurs and their majority of nearly landless laborers, whereas villages where property was more equally distributed were more harmonious. Prosperous villages with extensive holdings of common land and forests did not have the same interests as poor settlements with few shared resources. Reactions to the Revolution in rural regions where the peasants were deeply religious were very different from reactions in areas where devotion to the Church was more tenuous, and experiences were different as well depending on whether a community’s residents spoke French or not as their everyday language.

Although many peasants may not have understood the details of the extraordinary events that began in Versailles and Paris in 1789, they quickly realized that their place in society had radically changed. One ex-seigneur complained that “the former vassals believe themselves to be more powerful than kings.’”5 After the night of August 4, landlords and their representatives no longer ran the local courts; nor could they compel the population to use their mill or their winepress. Local legal disputes, formerly settled in seigneurial courts, were now handled by locally elected justices of the peace. In their improvised courtrooms, litigants were allowed to present their arguments orally, instead of having to pay lawyers and clerks to write them down, and the justices tried to settle as many quarrels as possible through informal mediation. Cheaper and simpler than the courts of the old regime, the new system showed peasants that the Revolution did have some real benefits.

Although most peasants could not read, there were at least a handful of newspaper subscribers in even the smallest communities, and they shared the latest reports with their neighbors. The revolutionary assemblies bombarded humble village mayors with laws and decrees that they were expected to enforce, and public festivals, such as the federations of 1790, linked the population to national events. The formation of National Guard units, which took place even in rural villages, put arms in the hands of the peasantry and gave them the power to defend their interests. In the department of the Haute-Saône alone, thirty villages with populations of under six hundred had their own guard units.6 In the early years of the Revolution, rural National Guards served primarily as a local police force and as a symbolic presence at patriotic ceremonies; membership was not particularly onerous. When the National Assembly called on the guardsmen to help pressure local priests to take the oath supporting the Civil Constitution, however, some of them found themselves uncomfortably at odds with their fellow villagers.

From 1789 on, the middle-class lawyers who dominated the revolutionary assemblies consistently promoted the idea that property-owners should be able to do whatever they wanted with their land and the crops it produced. This individualistic ideal was rooted in the economic theories of the eighteenth-century Physiocrats and articulated in numerous articles in the Encyclopédie, but few peasants were prepared to embrace it, despite lectures from the editors of the Feuille villageoise, who scolded them, with exasperation, that “you want the big producers, the landowners, to hire you and raise your wages, and you don’t want them to have the right to sell the fruits of their fields.” The rural code enacted by the National Assembly on September 28, 1791, contained bold language promising that landowners were “free to vary at their will the cultivation and management of their lands, to manage their harvests as they wish, and to dispose of all the products of their property within the kingdom and outside of it.” From the peasants’ point of view, this meant that landowners, often outsiders to the village, could disregard long-established practices that protected the poorer members of the community, such as requirements that all village livestock be allowed to graze on the fields once the grain had been cut. Recognizing that their effort to implement free-enterprise principles in the countryside was likely to encounter resistance, the authors of the rural code added that landowners’ freedoms were limited to those that could be exercised “without harming the rights of others, and while conforming with the law,” a qualification that protected gleaning and pasturing rights.7 Many of these traditional limitations on land use persisted long into the nineteenth century.

Many peasants had hoped that the changes wrought by the Revolution would give them the chance to acquire land of their own or expand their holdings. The sale of the church lands, and later of properties confiscated from nobles who fled the country, might have offered them such opportunities, but in fact only a relatively small fraction of these holdings initially wound up in peasant hands. Revolutionary administrators, under pressure to bring in as much money as possible, considered it most advantageous to sell these national lands as large parcels rather than subdividing them to make them affordable for poorer peasants. As a result, the majority of them were purchased by wealthy urban residents rather than villagers. The nobleman Gaston de Lévis noted that the “capitalists” who “bought large areas” then often “sold them in small units to poorer city-dwellers and peasants,” so over the years, an increasing amount of land did wind up in the hands of the peasantry.8 In 1791, however, it was easy for peasants to conclude that they were not yet receiving the benefits the Revolution had promised them.

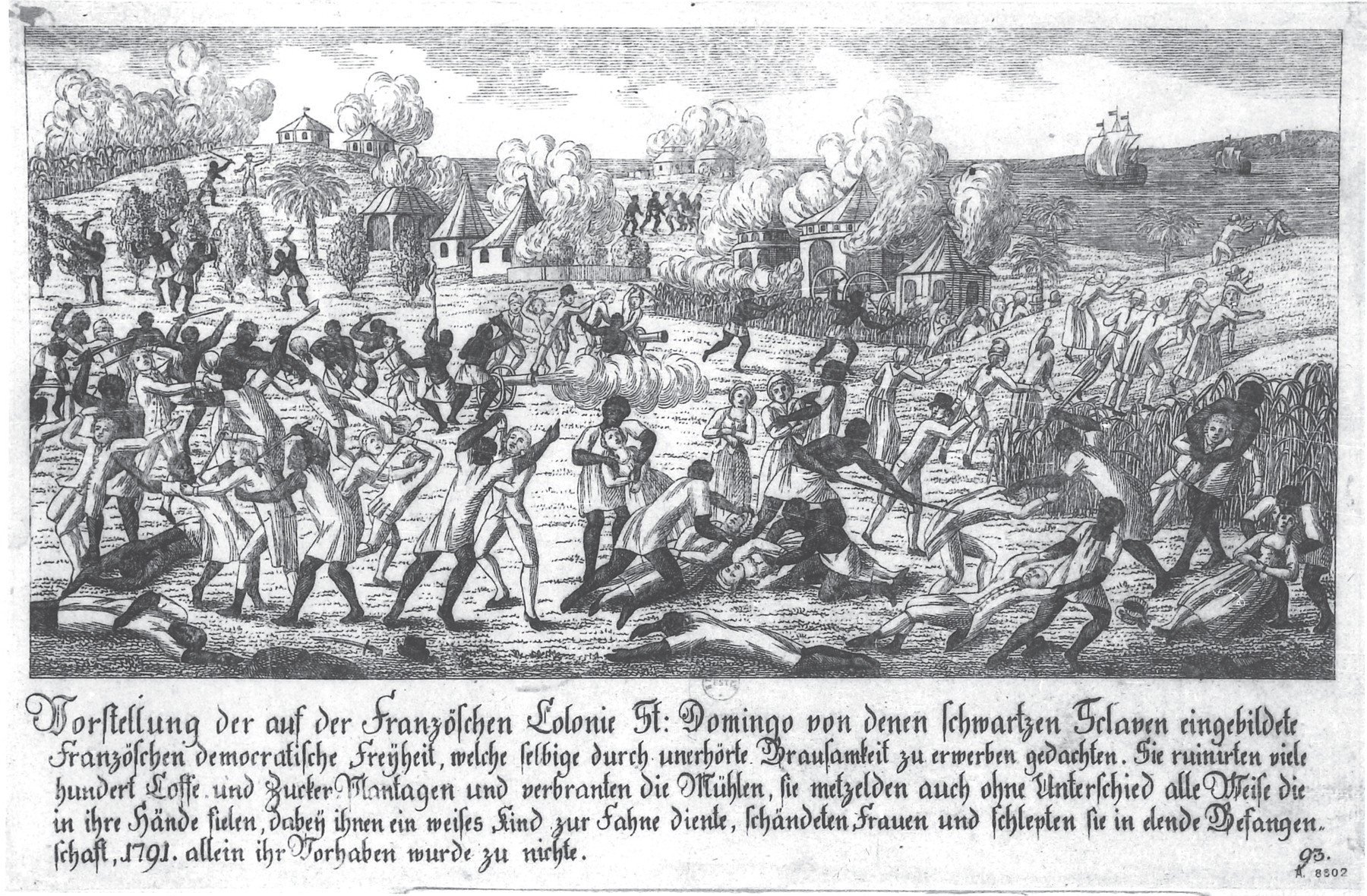

Faced with a restive urban population in Paris and a peasantry unconvinced that the Revolution favored its interests, the newly elected Legislative Assembly also quickly found itself dealing with a crisis in France’s most valuable overseas colony. A massive insurrection among the enslaved blacks in the North Province of Saint-Domingue began on the night of August 22, 1791, and quickly swept through the wealthiest sugar-growing district of the island. The rebels set fire to the highly flammable sugarcane fields, creating columns of smoke that could be seen for miles, and attacked their masters’ houses, killing a number of plantation owners and managers. The white colonists, convinced that black slaves could never have organized such an effective revolt on their own, blamed metropolitan philanthropes (lovers of humankind) like Brissot for putting explosive ideas about liberty into their heads. Distrustful of the legislators in France, the leaders of Saint-Domingue’s Colonial Assembly appealed to the neighboring British and Spanish colonies for help before they communicated with their own government. This convinced Brissot and his supporters that the colonists preferred a foreign occupation of their island over the arrival of French troops to put down the rebellion, because the latter might bring revolutionary ideas with them.

UPRISING IN SAINT-DOMINGUE: The revolt in the French Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue (today’s Haiti) was the largest challenge to slavery in history. Its outbreak forced the French revolutionaries to confront the contradiction between their principles of liberty and equality and the reality of the oppressive plantation system. This fanciful illustration of the uprising was produced in Germany, hinting at how the German population may have viewed events in France. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Some of the participants in the black uprising may indeed have heard echoes of French revolutionary debates, which the colonists had freely discussed among themselves. But the insurgents drew more motivation from a widespread rumor that the French king wanted to improve their lot by granting them three days a week to work for pay and earn money that they could use to purchase their own freedom. The black population also found the revolutionary campaign against the Church hard to understand. Some of the colony’s Catholic priests maintained contacts with the insurrection’s leaders and served as intermediaries, attempting to limit the violence of the revolt. Paradoxically, the Saint-Domingue slave uprising thus began as a movement more sympathetic to the values of throne and altar than to the abstract principles of liberty and equality that had been proclaimed in 1789 but not applied to the colonies. Metropolitan revolutionary ideas had more of an impact on Saint-Domingue’s free people of color, who began their own insurrection in parts of the island’s West and South provinces almost simultaneously with the slave revolt in the north. Determined to claim the rights promised to them in the May 15 decree, they did not call for the freeing of the slaves, since many of them were themselves plantation owners, but they did supplement their own forces by arming some of the blacks.

Because of the time it took for ships to cross the Atlantic, news of the uprisings in Saint-Domingue only reached Paris at the end of October 1791. The reports put the revolutionary advocates of liberty and equality in an awkward position. Olympe de Gouges, whose play Mirza and Zamore, first performed at the end of 1789, had brought the abolitionist cause to the stage, now denounced the violence of the black insurgents: “Men are not born to be in chains, and you prove that they are necessary.” Brissot and the Friends of the Blacks had always insisted that they were advocating only a gradual and peaceful phase-out of slavery, not an upheaval that would endanger the lives of the whites and the national economy. They denied that their criticisms of slavery could have set off the revolt. Just as the colonists immediately suspected a Jacobin conspiracy behind the slave insurrection, the white reformers jumped to the conclusion that the movement must have been inspired by royalists. That idea that seemed plausible, because the uprising had begun at almost the same time as the arrival in Saint-Domingue of the news of the king’s attempted escape from Paris.9

The government dispatched six thousand troops to Saint-Domingue, the beginning of a military deployment that would continue throughout the revolutionary decade. Barnave assured Marie-Antoinette that the news would make “all the commerce and all the manufactures of France pronounce in favor of the government and against the troublemakers.” As the months went by without a resolution of the crisis, Brissot and his allies blocked additional military forces until the white colonists agreed to grant rights to the free people of color. While the legislators in Paris fought verbal battles over the issue, whites and people of color in the colony’s administrative capital, Port-au-Prince, clashed on November 21, 1791. Half of the city’s buildings burned in the fracas. The troubles in Saint-Domingue sent sugar and coffee prices soaring in France, leading to riots at food shops. At the Jacobin Club, speakers proposed that members show their patriotism by renouncing both products until their prices came down, but few Parisians were prepared to go without the luxuries that had become the symbol of civilized urban life. Called on to put down the disturbances, the commander of a Paris National Guard unit recognized that his men would not obey him, because “they were part of the people more than they were National Guards.”10

In addition to the disputes about colonial policy, the Legislative Assembly soon found itself divided by struggles about the émigrés and the Church that brought the king into direct confrontation with the majority of the deputies. For the more radical deputies, such as the Girondin leader Vergniaud, there was no doubt that “clemency… has merely emboldened the enemies of liberty and the Constitution,” and that “the time has now come to clamp down on their criminal audacity.”11 A decree passed on November 9, 1791, took aim at the royal princes who were lobbying foreign governments to intervene in France. The decree ordered them to return to the kingdom by the beginning of 1792 or else face execution if they ever reentered French territory. Louis XVI could hardly endorse such a draconian measure against his own brothers, and he promptly exercised his constitutional right to veto the law. A second law, passed on November 29, 1791, tried to put a stop to disruptive agitation by refractory priests. It offered those who were willing to tone down their hostility to the new government the option of taking a civic oath that did not involve an explicit acceptance of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy in its entirety. Again the king used his veto, convincing the revolutionaries that he was determined to protect their worst enemies.

Fearing that the survival of the Revolution and the country was at stake, the patriot leaders embarked on a high-stakes gamble: led by Brissot, they began to campaign for a declaration of war against the foreign powers that were providing refuge to the émigrés. In the spring of 1790, when the question of the king’s right to declare war had been debated, the supporters of the Revolution had argued that a free people would never embark on a war of aggression. Now, in a series of vehement speeches at the Jacobin Club, Brissot, citing examples from antiquity and the recent American war of independence, proclaimed that “a people which has conquered its freedom, after twelve centuries of slavery, needs a war to consolidate it, to test itself, to show that it is worthy of freedom.” Adopting the exalted language common at the Society of the Friends of Truth, where Brissot and his supporters often appeared, he announced that “such a war is a sacred war, a war ordained from on high, and like the heavens, it will purify our souls.” A war for liberty would also be a war for equality: “By mixing men and ranks, elevating the plebeian, bringing down the proud patrician, war alone can make all equal and regenerate souls.”12

If the king sought to betray the country by committing treason, Brissot argued, so much the better: “We need great betrayals: they will save us, for powerful doses of poison still exist in France, and it will take strong explosions to expel them.” The American revolutionaries, he recalled, had emerged strengthened despite the treachery of Benedict Arnold. If the French launched a “crusade for universal freedom,” Brissot promised, they could be sure of support from the populations of other countries. “All the nations secretly invite it,” he said. “It will topple all the foreign Bastilles.”13 He was not worried about the disorganization in the French army caused by the emigration of aristocratic officers. Fighting for a noble cause, he insisted, French soldiers would surely be invincible. Brissot’s close ally, the banker Étienne Clavière, claimed that war would restore the value of the Revolution’s depreciating paper currency, the assignats, which he alleged was being deliberately undermined by foreign governments. For her own reasons, the influential Madame de Staël joined in the campaign for war: her lover, the handsome comte de Narbonne, had just been appointed war minister and hoped to distinguish himself by conducting a limited offensive against Trier, a small German state where a number of émigrés had taken up residence.

The Feuillants and moderates in the Legislative Assembly had grave doubts about such an adventure, but they feared appearing to defend the émigrés and the diehard opponents of the Revolution. Barnave emphasized to Marie-Antoinette the importance for the king of taking a firm position against the Austrian government’s protection of the émigrés in the German principalities close to the French frontier. In a secret letter to her longtime confidant Mercy d’Argenteau, the queen gave an assessment of the situation that was very different from Brissot’s unbounded confidence in French success. “I don’t need to go on at length to show how absurd this policy is: without an army, without discipline, without money, we are the ones who are going to attack.” Nevertheless, Marie-Antoinette explained, Louis XVI was going to support the demand for war. “The king is not free, he has to follow the general will, and for our personal safety here, he has to do what he is told.”14

Paradoxically, the most forceful critic of Brissot’s war policy was not a moderate or a royalist but rather the most consistent defender of radical democracy among the revolutionaries, Robespierre. In speeches at the Jacobin Club, he challenged Brissot’s assurance that the French would find broad support if they invaded foreign countries. “The most extravagant idea that can arise in the head of a politician is to believe that it is enough for a people to enter a foreign territory with military force to get them to adopt our laws and our constitution. No one likes armed missionaries,” he warned. In his view, before the French tried to bring the principles of liberty and equality to others, they needed to win their struggle against their enemies at home. He also feared that war would provide the king and his ministers with an opportunity to subvert the constitution. Robespierre’s sober assessment of the risks of trying to export democratic ideas through armed intervention was prophetic, but initially, its main effect was to isolate him from the mainstream of the French revolutionary movement. Madame Roland made an unsuccessful last attempt to keep him from turning against his former allies; after a private meeting, she wrote to him, “I saw, with pain, that you are persuaded that any intelligent person who thinks differently from you about the war is not a good citizen.” Robespierre’s position also put him at odds with the patriotic volunteers who were eagerly joining the army. “How enthusiastically we would go into combat!” one of them wrote. “In fighting for the cause of our country we would at the same time be fighting for that of all peoples.”15

The Austrian government attempted to avoid an open conflict by urging local German rulers to curb the émigrés’ activities, but Vienna promised to fight back if the French took military action. As rhetoric in Paris became increasingly heated, the Austrians and their longtime rivals, the Prussians, made a secret agreement to act together in case of war. By this time, Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette had decided to take the risk of helping Brissot achieve his goal. Fersen, who had succeeded in returning to Paris for a secret meeting with the queen in mid-February, reported to the Swedish king that the royal couple had decided that “there is no way of restoring their authority except through force and foreign assistance”: in other words, the king would help plunge the country into war in the hope that his own armies would be defeated and that foreign troops would rescue him.16 The king’s decision was signaled by his appointment, on March 15, 1792, of a “Jacobin” ministry dominated by close allies of Brissot. Although Brissot himself, as a member of the legislature, was barred from holding a ministerial position, he was considered the real power behind the ministry. Clavière, the new finance minister, had been a close associate of Brissot’s even before the Revolution, and the interior minister, Roland, was the husband of the woman at the center of the “Brissotin” network. Foreign policy was put in the hands of Charles-François Dumouriez, an older military officer who had long argued for an aggressive policy toward Austria.

As part of this awkward agreement between the outspoken revolutionary patriots and the monarch, Brissot achieved one of his most cherished objectives. On April 4, the king approved a law granting full civil and political rights to the free population of color in the French colonies. It also provided for the dispatch of a civil commission to Saint-Domingue with powers to replace the white colonists’ local assemblies with new bodies in which they would share power with their mixed-race rivals. For the first time in history, a European government declared that nonwhites could be full citizens in its empire. The law of April 4 said nothing about ending slavery, however, and the civil commission it established was to be accompanied by a new contingent of six thousand troops, to help defeat the uprising that had begun the previous August. By overturning the National Assembly’s concession of granting extensive autonomy to the colonies, the law put them under the direct control of the metropole. Opposition in the Legislative Assembly blocked the appointment of the mixed-race spokesman Julien Raimond to the commission, but on the other side of the Atlantic, members of Raimond’s mixed-race group had already obtained major concessions even before news of the April 4 law reached Saint-Domingue. Convinced that the white colonists’ rigid opposition to any change in the system of racial hierarchy was making it impossible to defeat the slave rebellion, the colony’s governor and other officials who had already been sent from France forged an alliance with the leader of the free colored movement, Pierre Pinchinat, and the mixed-race Conseil de paix et d’union (Council of Peace and Union) that he had created as an alternative to the all-white Colonial Assembly.

Brissot’s victory on the colonial front was quickly overshadowed by the consequences of his and Dumouriez’s war policy. Dumouriez, who had been born close to France’s northern border with Belgium, had strongly supported the revolt there against Austrian rule in 1789–1790. He argued that the troops the Austrians had stationed in the area after their defeat of the Belgian uprising were a menace to French security, and he shared Brissot’s confidence that “these provinces are permeated by the spirit of liberty” and would eagerly welcome French troops if war broke out. On April 20, 1792, Louis XVI gave Dumouriez the green light for his policy by going to the Assembly and calling for a declaration of war. A moderate deputy, Louis Becquey, found himself echoing the arguments that the radical Robespierre had made in his debate with Brissot: “We shall appear as aggressors; we shall be portrayed as a disorderly country which upsets the peace of Europe in defiance of treaties and our own laws.”17 Despite this opposition, Brissot’s heady rhetoric and Dumouriez’s brash confidence carried the day: only six deputies voted against the declaration.

Enthusiasm for the war was not limited to politicians: the ranks of the army were filled by patriotic volunteers. When news of the declaration of war reached the Alsatian city of Strasbourg, a fortified city on the Rhine that was bound to play a major part in the struggle, the local mayor called on a young military officer with musical talents, Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle, to compose a patriotic song to mark the occasion. In one night, Rouget de Lisle jotted down six stanzas, beginning with the words, “Allons enfants de la patrie! Le jour de gloire est arrivé” (Arise, children of the fatherland! The day of glory has arrived). Meant to rouse nationalist fervor, the lyrics called upon citizens to “form your battalions” and “let an impure blood water our fields.” The words were fitted to a stirring melody and titled “War Song for the Army of the Rhine.” Within two months, as soldiers circulated around the country, the new song had reached the other end of France. It was performed at a patriotic ceremony in Marseille on June 22, 1792, and a local newspaper provided the first printed version the next day, allowing the local volunteers to take copies with them as they headed north.

The declaration of war transformed the nature of the French Revolution. To be sure, none of those who launched it knew they were starting a conflict that would draw in all the powers of Europe, or that this conflict would continue, in one form or another, for more than twenty years. Brissot and Dumouriez, who anticipated popular uprisings that would overthrow the other governments of Europe, underestimated the determination of their adversaries and the resources they would be able to mobilize. So did Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, who assumed that the shaky revolutionary regime would quickly collapse. As Robespierre had warned, the faith of the revolutionary warhawks that other peoples would eagerly welcome the French proved unfounded. Brissot’s expectation that war would push the Revolution in a more radical direction, however, was confirmed. The need to recruit soldiers from among the ranks of the passive citizens, that is, the poor, and to call on the entire population to make sacrifices for the war effort, made it ever more difficult to defend their exclusion from political participation. It even created openings for women to demand recognition for their contributions by volunteering to take up arms. Two young women in particular, the Fernig sisters, so impressed the general defending Valenciennes that he promised to “put them in the line of fire at the first opportunity,” according to one news report. Only in April 1793 were women officially barred from combat.18

These expressions of women’s patriotism did not result in an expansion of their rights. The Legislative Assembly did make a major change in policy with respect to the nagging question of compensation for feudal dues, however. This was an issue that mattered intensely to millions of peasants whose sons would now be called on to serve in the military. A law enacted on June 18, 1792, reversed earlier legislation that had favored former seigneurs: landowners who wanted to make peasants pay them compensation for abolished feudal dues would now be the ones who would have to come up with documentary evidence to justify their claims. The Assembly’s action shored up peasant support for the revolutionary government at a time when the war crisis was forcing the government to make ever more exacting demands on the population.

As the war pushed the Revolution in a more democratic direction, it also made political conflicts more explosive. When the Brissot ministry ordered the release of the soldiers imprisoned after the army mutiny in Nancy in 1790, they were hailed as heroes who had exposed the tyranny of their aristocratic officers, a risky message to spread as the troops were preparing for battle. An elaborate procession welcomed them to Paris. Moderates responded by organizing a “Festival of the Law” to honor a small-town mayor who had been killed by a crowd demanding bread. The Révolutions de Paris complained that the festival’s organizers “had set their hearts on humiliating and subduing the people” by “supposing that it needed to be constantly recalled to order.”19 All sides increasingly saw their opponents not just as misguided but as traitors to the country who needed to be physically eliminated, even if this meant severely limiting the freedoms that the Revolution had promised to protect.

Ironically, however, it would not be Brissot and his Girondin allies who would emerge to lead the movement toward greater democracy and radicalism, but Robespierre and the more extreme revolutionaries. The Incorruptible’s paranoid fear that the military effort would allow for a restoration of royal authority was soon shown to be wrong. Robespierre’s concern that war would create opportunities for ambitious and charismatic military leaders to attempt to seize power was more prophetic, however. The man who ultimately proved the point was not one of the aristocratic generals who led the French forces in 1792, but an obscure artillery lieutenant whose name was completely unknown outside of the remote island of Corsica when the war began. In 1792, the ambitious military man most in view was not Lieutenant Napoleone Buonaparte, who was still debating whether to commit himself to the French Revolution or to a movement for the independence of his native island, but the minister Dumouriez.

In accordance with Dumouriez’s plan, French troops quickly crossed the Belgian frontier, but it immediately became clear that their expectations for a glorious crusade on behalf of liberty were far removed from the realities of warfare. “It is not with addresses, petitions, festivals and songs that one holds off experienced, disciplined troops skilled in tactics,” a veteran officer later explained to the politicians in Paris.20 When poorly prepared French soldiers were ambushed by Austrian defenders near Tournai and took heavy losses, the survivors turned on their own commander, General Théodore Dillon, hanging him from a lantern and burning his body. In the Legislative Assembly, the deputies responded to military setbacks by demanding stronger measures against the customary suspects, refractory priests and émigrés. Brissot and his legislative allies stepped up their attacks on what they called the “Austrian committee,” the secret council through which, they claimed, Marie-Antoinette was conspiring to sabotage the war effort. The king vetoed the harsh new laws against counterrevolutionaries, further fueling the distrust surrounding the court. Had the Austrians and their Prussian allies been more prepared for the war, they might have quickly taken advantage of the disarray caused by the initial French military setbacks and the political chaos in Paris, but their generals, sure of success, took their time preparing their campaign.

In Paris, disagreements about the conduct of the war divided the Jacobins. “Robespierre and Brissot, the two chiefs of the different parties, each have their partisans, and so war is declared, as unfortunate in the club as on the frontier. It puts us on the edge of the abyss,” Rosalie Jullien, a keen observer of politics, lamented to her husband. The military defeats made open conflict between the new Jacobin ministers and the king inevitable. On June 10, 1792, the interior minister, Roland, published an open letter to Louis XVI, drafted in large part by his wife, demanding that he take immediate measures against priests and others who were causing unrest. The king, Roland insisted, needed to understand the emotional force of the new passion for the country that the Revolution had created. “The fatherland is not just a word embellished by imagination; it is something tangible for which one has made sacrifices,” he wrote. If the king did not prove his loyalty, this intense devotion to the nation would force local officials in the departments to take “violent measures, and the angry people will add to them through its excesses.”21 No French minister had ever dared address a ruler in such a tone, and the king reacted swiftly by dismissing Roland and the other Jacobin ministers, who had only just been appointed in March. As the Jacobins voiced their outrage, Lafayette, who had long seen himself as the one man who could maintain the balance between the court and the revolutionary radicals, became increasingly alarmed. From his position at the frontier, where he was now commanding one of the French armies, he sent a strongly worded denunciation of the Jacobins. To those who remembered how Roman generals had used their soldiers to destroy the republic, the man who had been a national hero in 1789 now began to appear as a menace to the Revolution.

If Louis XVI and Lafayette were unwilling to accept the dictates of the pro-revolutionary militants, the revolutionaries were equally unwilling to back down in the face of the king’s resistance. On June 20, 1792, a week after the ministers’ dismissal, a massive crowd of twenty thousand to twenty-five thousand men and women, many of them National Guardsmen carrying weapons, forced its way into the meeting hall of the Legislative Assembly and then invaded the neighboring Tuileries Palace, where they surrounded the king and kept him backed up against a window for several hours. Louis XVI faced this ordeal with unexpected courage. He allowed protesters to put a red “liberty cap,” a symbol of sans-culotte militantism, on his head, and he drank a toast to the nation, but he refused the crowd’s demands to withdraw his vetoes and recall the Jacobin ministers. He insisted that he was exercising his legitimate constitutional powers. Even more overt anger was directed at the queen, but she was not physically assaulted either. Toward evening, the pro-revolutionary mayor of Paris, Pétion, belatedly appeared at the palace. Determined not to provoke a confrontation with the sans-culottes that might end in bloodshed, like the massacre of the Champ de Mars a year earlier, he had accepted the demonstration organizers’ promise that they would not resort to violence. The king reproached him bitterly for allowing the invasion of the palace. Marie-Antoinette, who had made it her business to win the sympathy of the National Guard officer assigned to the palace so that she could pump him for information about public opinion, was also furious. The officer had failed to protect them. “She glared fiercely at me and spoke in a tone that betrayed all her anger,” he later recalled.22

The protest had been organized by Jacobin militants and activists in the Paris sections, the new subdivisions of the city, each of which had its own assembly and National Guard unit. It was the first such political intervention by the ordinary people of Paris since the October Days in 1789. Unlike the October Days, however, the journée of June 20 did not break the political deadlock that threatened to paralyze the government. Louis XVI’s firm and dignified behavior in the face of the demonstrators spurred a reaction in his favor, especially in the provinces. Over seven thousand Parisians signed a petition denouncing Mayor Pétion for his failure to take active measures to stop the demonstration, and the conservative administrators of the department suspended him from office. Lafayette left his army at the frontier to come to Paris and denounce the militant movement. Radical journalists accused him of threatening a “civil war by means of which he hopes to impose a tyrannical protectorate.” “If, instead of talking, Lafayette had acted,” a National Guard officer who sympathized with him later wrote, “it would have been the end of all the Jacobins in the world.”23

In the Legislative Assembly, a constitutional clergyman, Adrien Lamourette, tried to heal the inflamed political divisions. On July 7, he called on the deputies to set aside their differences and embrace one another. As men who had barely spoken to each other for months shared emotional hugs, Louis XVI hurried over from his palace to renew his oath of support for the constitution. The deputies’ enthusiastic participation in “the kiss of Lamourette” revealed the emotional appeal of national unity, but the moment of reconciliation was fleeting. Both moderates and radicals had become convinced that true harmony could only be achieved by eliminating their opponents. Only two days after Lamourette’s intervention, Brissot unleashed a renewed attack on the king. Demanding that the deputies declare “the country in danger,” he insisted that France faced a crisis because “its forces have been paralyzed”: “And who has paralyzed them?” he asked. “One man: he whom the constitution has made their leader.”24

Brissot demanded a special committee to decide whether the king’s actions amounted to a violation of his solemn oath to uphold the constitution. He also called for the elimination of the distinction between “property-owners and non-property-owners” that kept the latter from having the status of active citizens. Outside of the Assembly, “the firmest patriots and the republicans of Paris” began to organize a movement to force the king from the throne. These organizers included the Jacobin leaders, their militant allies in the Paris sections—where efforts to exclude the poor had already broken down—and the radical journalists. They aimed to “carry out a second revolution[,] whose necessity they recognized,” as one of them later put it. By the first week of July, Paris newspapers such as the Trompette du Père Duchêne were outlining the radicals’ program, calling for a popular uprising to force the Legislative Assembly to suspend the king’s powers, the installation of a provisional government to replace the royally chosen ministers, and elections for a national convention to determine the future of the monarchy and draft a new constitution.25

The anniversary of the storming of the Bastille provided the Paris radicals an opportunity. As in 1790 and 1791, a great gathering of fédérés, patriotic volunteers from all over the country, was scheduled in the capital for a celebration. The armed participants would then be sent to the frontiers to strengthen the army. While they were in Paris, however, the Paris radicals decided that the fédérés, who had been selected for their revolutionary enthusiasm, could provide the muscle to overcome Louis XVI’s resistance. Among the provincial militia groups, the fédérés from Brest and Marseille had especially radical reputations. As soon as the men from Marseille landed from the riverboat that brought them down the Seine, they provoked a street fight with some well-dressed Parisians who had insulted them. “The poorer people of Paris took the side of the Marseillais,” the chronicler Ruault wrote.26 The men from Marseille not only brought a new militancy to the streets of Paris: they also brought the first printed copies of the new patriotic song that Rouget de Lisle had composed in April. The stirring melody and the bellicose words of this “song of the Marseillais” became indissolubly identified with the group that brought it to Paris. “La Marseillaise,” now France’s national anthem, remains the one melody from the revolutionary era that is immediately recognizable around the world.

The Legislative Assembly was reluctant to endorse the radicals’ demands or the strong-arm tactics of the fédérés, but even the moderate deputies recognized the danger of the situation. The country was bracing for a foreign invasion, and the head of the government and his ministers were suspected of collusion with the enemy. On July 22, a week after the celebration in honor of Bastille Day, while the out-of-town fédérés were still in the city, the Assembly finally accepted Brissot’s recommendation to declare the “country in danger.” Its decree ordered all local governments to take any measures they thought necessary to respond to the crisis, without waiting for instructions from the king or his ministers. Rendered virtually powerless by this decree, the ministers the king had appointed to replace the sacked Brissotins resigned, creating a vacuum in the executive branch and demonstrating that the constitutional monarchy had ceased to function. Nevertheless, the Assembly’s moderates were still reluctant to support firm measures. They defeated a motion to censure Lafayette, for example, even after he announced he would use his troops to oppose any threats against the king.

As the constitutional system inaugurated just a year earlier broke down, both sides prepared for a violent struggle. Inside the Tuileries Palace, the members of the royal family feared for their lives. Although the king and queen distrusted many of the National Guardsmen assigned to protect them, they felt they could count on the loyalty of the units of professional Swiss soldiers who shared that duty. Armed with artillery, the defenders could at least hope to inflict heavy casualties if the palace was attacked. Perhaps this would enable the royal couple to hold out long enough for a rapid advance of the Austrian and Prussian armies to rescue them. By late July, the forces of the two foreign monarchies were finally ready to cross the French frontier. To the frustration of the French émigrés whose presence in Germany had done so much to trigger the war, the Austrians and Prussians refused to give them a leading role in the invasion, fearing that their presence would inflame resistance. Instead, the allied powers insisted that they were intervening only to uphold Louis XVI’s legitimate authority. On July 28, 1792, the commander of the allied army, the duke of Brunswick, issued a manifesto warning that the population of Paris would be severely punished if the royal family was harmed.

The threats in Brunswick’s manifesto convinced supporters of the Revolution that there was no more time to spare in dealing with the king. Men like Fournier l’Américain, a former Saint-Domingue colonist who had helped lead the assault on the Bastille and the October Days march in 1789, had concluded that “the French legislators only showed real energy when the people rose up and forced them to act.”27 On August 3, 1792, the assembly of the Mauconseil section of Paris issued a manifesto demanding that the Legislative Assembly remove Louis XVI from the throne. If the legislators did not do so, the people of Paris would use force to oust the monarch. Behind the scenes, a secret committee of militants from the Cordeliers Club and the sans-culotte movement prepared to launch the National Guard battalions of the Paris sections against the Tuileries. The militants calculated that if their movement succeeded, radical politicians would have no choice except to satisfy their demand for the elimination of the opponents of the Revolution.

Brissot and the Girondin deputies thought the threat of an insurrection would intimidate Louis XVI into reappointing the ministers he had dismissed in June and letting them direct the war effort, but they were hesitant about completely overturning the constitution. The consequences of an armed popular uprising were unpredictable. They worried that the army might not accept the outcome of a violent uprising in Paris, and that Lafayette might find support among his troops to intervene against it. Brissot himself feared that the country was not ready for a radical shift from monarchy to republic. In his memoirs, which he wrote after his own defeat and arrest a year later, he recalled that he “knew very well that this single word [republic] would have offended many people, and perhaps caused the failure of the revolution that was coming.”28 Earlier, the Girondin newspapers had joined in agitating for the deposition of the king, but now they began to transmit confusing signals, suggesting that a direct confrontation should be postponed. After the decisive clash, the Girondins’ apparent last-minute doubts about the wisdom of overthrowing the monarchy by force would be used to discredit them.

Unlike the spontaneous and disorganized uprising that had led to the capture of the Bastille, the insurrection of August 10, 1792, was carefully plotted. Under cover of night, the activists summoned their troops and took control of the Commune, the government of Paris based in the Hôtel de Ville. They dismissed its elected assembly and replaced it with their own loyalists from the sections. For the next month and a half, this revolutionary Commune would compete with, and sometimes overshadow, the national government. Pétion, the mayor who had failed to prevent the mass demonstration on June 20, was put under house arrest, and the commander of the National Guard, suspected of being loyal to Lafayette, was summoned to the Hôtel de Ville and murdered. The brewer Santerre, a leading figure in the popular radical movement from the time of the storming of the Bastille, took his place, and the tocsin was sounded to summon the guard units, especially those from the militant sans-culotte strongholds of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine and the Faubourg Saint-Marcel. Inside the Tuileries Palace, the king’s defenders listened as church bells and drums sounded from all directions. By 6:00 a.m. on August 10, the section battalions were marching toward the Tuileries, armed with the long pikes that had become the favored weapons of the armed people. Inside the palace, Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette prepared themselves for what might be their last moments. As the king reviewed his troops, Marie-Antoinette tore a pistol from an officer’s belt and handed it to her husband, telling him, “Now is the time to show who you are.” But some of the National Guards who were supposed to defend the Tuileries now revealed their true sentiments, shouting, “Down with the traitor!” Then they abandoned their posts.29

REVOLUTIONARY PARIS: The densely populated city of Paris played a unique role in the revolutionary drama. The Bastille, the meeting halls of the revolutionary assemblies and clubs, the royal palace of the Tuileries, the seat of the city government at the Hôtel de Ville, and the working-class faubourgs, where insurrections often started, were all within close walking distance of each other. Credit: Richard Gilbreath.

Had Louis followed his wife’s prompting and allowed himself to be cut down at the head of his defenders on the steps of the palace, the result would have been fatal for the king, but it might have restored some luster to the monarchy. Instead, he turned to the former Jacobin National Assembly deputy Pierre-Louis Roederer for advice. Roederer, now a municipal official, persuaded him that the only way to save himself and his family was to abandon the palace and take refuge in the meeting hall of the Legislative Assembly. This response saved the royal family from a possible violent death, but it also made them prisoners. At the same time, it left the Legislative Assembly with the awkward question of what to do with them. To avoid violating the constitutional provision that forbade the king from being present during deliberations of the Assembly, the royal family was sequestered in the space normally reserved for the journalists who kept a record of the deputies’ speeches. There they stayed until late in the night while the legislators discussed their fate.

Louis XVI’s decision to abandon the Tuileries had disastrous consequences for his most loyal defenders, the Swiss Guards. By 9:30 a.m., the aggressive fédérés from Marseille had forced their way into the interior courtyard of the Tuileries. When they managed to grab two of the defenders and disarm them, the Swiss soldiers’ comrades responded with a volley. Firing into the densely packed crowd, the Swiss Guards’ guns claimed hundreds of victims; the final death toll of well over a thousand would make the journée of August 10 by far the bloodiest day of the Revolution in Paris. “The women ran through the streets crying and lamenting, because each of them feared a cruel loss,” Rosalie Jullien reported. Outraged that the Swiss had killed patriotic citizens even after the royal family was out of danger, radical activists were convinced that they had been victims of “a crime unheard of until this epoch that the court planned against the nation,” as the Révolutions de Paris wrote.30 Hearing the gunfire from his refuge in the Assembly hall, Louis XVI attempted to end the bloodshed by instructing the Swiss to cease fire, but it was impossible to deliver his order in the midst of the fighting.

The Swiss soldiers’ resistance infuriated the attackers, and once the attackers were able to overwhelm their opponents with their superiority in numbers, the result was gruesome. As Ruault recorded, “the people… went through all the apartments and massacred all the Swiss they found. The corridors, the offices, the attack, all the secret passageways and even the cupboards were searched; all the unfortunates discovered in these corners and byways were massacred; others were thrown alive from the windows, despite begging vainly for their lives, and run through with pikes on the garden terrace and the pavement of the courtyard.”31 Crowd members destroyed the furnishings of the palace. As they ransacked cabinets and drawers, they also found hundreds of letters and documents offering evidence of the court’s opposition to revolutionary policies.

The violence at the Tuileries and the idea that the king’s troops had deliberately opened fire on the people made any effort to stand up to the demands of the radicals impossible. Bloodshed was not confined to the palace: crowds lynched a royalist journalist and the moderate ex-deputy Clermont-Tonnerre, as well as a number of individuals accused of looting. The printing shops of royalist and moderate newspapers were attacked, and numerous ex-nobles, royal officials, and refractory priests were imprisoned. The offices of the white colonial slaveholders’ Club Massiac were raided and its papers seized. Sans-culotte militants not only went after living supporters of the monarchy but also its symbols, such as the equestrian statue of Louis XIV in the Place des Victoires and the statue of Henri IV on the Île de la Cité. Napoleon Bonaparte, who witnessed the attack on the palace from the window of a nearby building, mingled with the crowd afterward. “The anger was extreme everywhere one went,” he later recalled. “Hatred was in their hearts and could be seen on their faces, even though they were not at all from the lower classes.”32 The experience left him with a lasting distaste for popular violence.

With the radical Commune moving rapidly to seize power in the city, the Legislative Assembly had to act quickly to retain any influence at all. The Girondin deputy Gensonné put forward a motion to suspend the king from his functions, which would repeat what had happened after his attempted flight in June 1791. The deputies called for the election of a National Convention that, like the National Assembly of 1789, would have full authority to express the will of the people. The arguments that Sieyès, Barnave, and so many other politicians had made to justify excluding the poor from participation in politics were tossed aside; the legislators now decreed that any man over twenty-one years of age who was gainfully employed and who was not a household servant would be allowed to participate in the elections. At a time when many of the American states still had wealth qualifications for voting, revolutionary France became the first country in the world to embrace universal manhood suffrage.

On August 11, the Assembly passed a series of additional emergency measures. The royal family would be held as prisoners, and a special guardian was appointed for the Dauphin, the child heir to the throne, to remove him from the influence of his parents. Royal ministers were replaced with a new Executive Council that included Roland and Clavière, members of the Brissotin team named the previous March. But the council also included several new faces, of whom the most important was Georges Danton, who was now closely associated with the revolutionary Commune. Although he had held only a modest position as second assistant to the Commune’s chief prosecutor when the August 10 insurrection broke out, Danton quickly filled the vacuum of leadership created by the uprising. For a crucial six weeks, until the newly elected Convention met on September 20, 1792, he was the one figure capable of dominating both the insurrectionary forces and the legislature. The former, he remarked, had been unleashed by what he described as “this so indispensable supplement to the revolution of July 14.”33 The latter, at this point, was struggling to keep the country together in the face of a crisis that made even the earlier revolutionary journées seem tame. Physically imposing, and, like Mirabeau, scarred by a childhood bout of smallpox, Danton stood out among the Revolution’s great orators. He had a genius for improvisation: very few of his speeches were written out in advance and he rarely bothered to have them circulated in printed form. His appointment as minister of justice was meant to give the emergency Executive Council appointed to run the government credibility with the militant movement that had just overthrown the monarchy.

Danton and his colleagues had their hands full trying to satisfy the revolutionary activists in Paris while keeping some control over the rest of the country and dealing with the enemy invasion. In the capital, the victorious radicals demanded swift punishment for the political suspects they blamed for the “conspiracy” that had resulted in the deaths of so many patriots on August 10. The Legislative Assembly at first tried to defend the principle that all defendants should be judged according to normal procedures, but on August 17 it bowed to demands from Robespierre and others and agreed to establish a special Revolutionary Tribunal to handle their cases. Its judges and jurors were chosen for their patriotic convictions, and their verdicts could not be appealed. This first Revolutionary Tribunal operated only for three months, but it set a precedent for the creation of special political courts that would be revived on a much larger scale in 1793 and 1794. The first defendants convicted by the court and executed in accordance with its decisions included court officials, the commander of the Swiss Guards, and the royalist journalist Barnabé Farmian Durozoi, the first of many writers to find that the constitution’s guarantee of press freedom was no protection in the heated revolutionary atmosphere.

The Revolutionary Tribunal’s trials attracted large crowds of cheering spectators who often insulted the defendants as they were taken to be executed. The editor of the tribunal’s official bulletin defended their behavior, calling it an expression of “the passion of a free people, satisfied to see itself delivered of an enemy.” The executions, conducted by Jacques Ménétra’s old friend Henri Sanson, were carried out using the guillotine, the mechanical beheading machine destined to become the Revolution’s most enduring symbol. Developed in response to a motion made in 1789 by the National Assembly deputy Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, the guillotine was intended to give victims a swift and painless death, in contrast to the protracted and painful methods of capital punishment used under the old regime. “In less than two minutes, everything was over,” Adrien Colson recorded after witnessing a double execution.34 The guillotine’s introduction also represented a victory for equality: all those condemned, regardless of their social status or their crime, would now be put to death in the same way. The guillotine was first used on common criminals in April 1792; the executions ordered by the Revolutionary Tribunal linked it indelibly with revolutionary politics.

The outgoing deputies of the Legislative Assembly and the provisional ministers named after August 10 hardly had time to think about the consequences of their adoption of the guillotine as an instrument of political vengeance. They were more concerned with defining the principles that the new constitution would embody, although it would be created not by them, but by the National Convention they had summoned. More emphatically than ever, the revolutionaries promised to create a society based on the principles of liberty and equality. The elimination of the distinction between active and passive citizens marked a major extension of the idea of equality, even if Danton felt obligated to insist that they were not aiming for “the impossible equality of goods, but an equality of rights and of welfare.” The Constitution of 1791 had been based on the premise that liberty and equality were compatible with a monarchical form of government, but the events of August 10 and the ongoing war now ruled out any such compromise. A proclamation drafted by Danton and issued on August 25, 1792, told the population that “the French people and the kings confront each other, already the terrible struggle begins, and in this combat… there is no choice but victory or death.”35 As in July 1789, when the storming of the Bastille had set off “municipal revolutions” across the country that put power in the hands of the movement’s supporters, news of the August 10 uprising in Paris led to considerable turmoil in local governments. Radicals in the departments, including Goujon in the Seine-et-Oise, began to oust their moderate opponents.

As the new power-holders in Paris set a radical course, the greatest threat was from Lafayette, who had already strongly condemned attacks on the constitutional monarchy in June. When the Legislative Assembly sent three deputies to his headquarters to make sure of his loyalty, the man who had been the first to propose a declaration of rights in 1789 showed how alienated he had become from the radical direction of the Revolution: he had them arrested. But Lafayette had lost sway over his men. “The news of the ouster of the king… spread joy and happiness among our volunteers,” one soldier observed. “‘No more king! No more king! that is their cry.’” When Lafayette tried to make his men swear to defend the monarchist constitution of 1791, they refused.36

Recognizing that his effort to oppose the overthrow of the monarchy had put him in danger, Lafayette abandoned his troops and gave himself up to the Austrians, who promptly imprisoned him. In Paris, a newspaper announced that Philippe Curtius, the proprietor of the wax museum, “having recognized his misjudgment of the traitor Lafayette who was for a long time one of the main attractions of his display,… had cut off the head of this untrustworthy hero.” The general, to be sure, continued to see himself as a supporter of “the people, whose cause is dear to my heart, and whose name is now profaned by brigands.”37 But he and most of the other “men of 1789” who had led the Revolution in its early stages were now totally discredited.

As elections for deputies to the Convention began in late August, the news from the military front turned increasingly dire. The Austro-Prussian forces were advancing rapidly. First the key fortress town of Longwy and then the even more strategic city of Verdun, the last major obstacle on the road to Paris, surrendered to the Prussians on August 29 without a struggle. The news of the loss of Verdun caused panic in the capital. Danton exhorted the citizens to redouble their efforts, calling on all able-bodied men to volunteer for the army and demanding searches of the homes of potential political suspects. “The tocsin we are sounding is not an alarm signal,” he told the deputies on September 2, 1792. “It is the call to charge against the country’s enemies. To defeat them, gentlemen, we need to dare, to dare again, and France will be saved!”38 The nineteenth-century statue of Danton summoning the French to repel the invaders that stands today on Paris’s busy boulevard Saint-Germain captures something of the great tribune’s revolutionary energy.

For the most committed activists, however, words alone, even the soaring rhetoric of a Danton, were not enough when the survival of the Revolution was at stake. As Danton was addressing the Legislative Assembly, militants from the Commune and the sections were taking over the prisons in the city, which were crowded with hundreds of suspects who had been arrested in the wake of the August 10 uprising. Claiming that the prisoners planned to take advantage of the departure of volunteers for the front to stage an uprising as the enemy army approached, they set up improvised “people’s courts.” Terrified captives—former nobles, refractory priests, relatives of émigrés, and ordinary people who had been swept up in the hunt for counterrevolutionaries—were brought out of their cells, given summary hearings, and, in most cases, thrust out the prison doors into the courtyards of the prisons or the streets in front of them, where they were immediately hacked to death. Among the prominent victims was the princess de Lamballe, who had been an intimate friend of Marie-Antoinette’s. Her body was torn apart in the street. Unable to get at the queen and the royal family, who were closely guarded in the Temple prison, some of those in the crowd waved her head under their window to send what one journalist called “a message worth heeding.”39

François Jourgniac Saint-Méard, an army officer and contributor to royalist newspapers, recorded the prisoners’ experience in My Agony of Thirty-Eight Hours, the most widely distributed contemporary account of the September massacres, which continued over the next three days. Saint-Méard had been arrested ten days before the start of the killing and was being held in the abbey of Saint-Germain, one of several confiscated religious buildings that had been turned into prisons. On the afternoon of September 2, killers arrived at the abbey and began taking victims down to the courtyard. From the window in his cell, Saint-Méard could hear what happened to those who were convicted. “It is completely impossible to express the horror of the profound and somber silence that prevailed during these executions,” he wrote. “It was interrupted only by the cries of those who were sacrificed, and by the saber blows aimed at their heads. As soon as they were laid out on the ground, murmurs arose, intensified by cries of ‘long live the nation’ that were a thousand times more terrifying to us than the terrible silence.”40

Saint-Méard was among the lucky prisoners who survived their ordeal. A friendly guard let him watch the interrogations of other prisoners, so he could see what tactics offered the best chance of winning an acquittal. At 1:00 a.m. on September 4, Saint-Méard found himself facing the improvised popular court. “Two men in bloodstained shirts, sabers in their hands, guarded the door,” he recalled. His hearing was interrupted while the judges quickly sentenced a priest to death. Returning to Saint-Méard’s case, they decided for acquittal. Three militants—a mason, an apprentice wigmaker, and one of the fédérés who had participated in the August 10 uprising, a typical sample of the militants involved in the massacres—accompanied him home to ensure his safety. When he tried to offer them a gift of money, they indignantly refused, insisting that they and the other participants in the killings were acting purely out of patriotic motives.

THE SEPTEMBER MASSACRES: Revolutionary militants’ violent reaction to the threat of foreign invasion permanently stained the movement’s reputation. The deputies elected to the National Convention realized that they had no choice but to adopt whatever measures were necessary to ensure the Revolution’s survival. Although revolutionary leaders were eager to put the outbreak of violence behind them, images of the killings were included with the widely distributed weekly Révolutions de Paris. Credit: © Musée Carnavalet / Roger-Viollet.

The Legislative Assembly and the delegates from the sections who made up the assembly of the Commune were informed of the massacres soon after they began on September 2. Both bodies sent representatives to the prisons to try to talk the killing squads into stopping their activities, but with no success. “We are doing our duty. Go back to yours,” one militant told them. Since the prisoners’ killers were drawn from the militia units of the sections, which constituted the only police force in the city, the authorities had no way to officially stop their activities. The vehement speech calling for “daring” that Danton, the minister of justice, had given on the morning of September 2 helped to create an atmosphere in which extreme measures seemed justified. Danton himself remained conspicuously silent throughout the three days of killings. Among the other leading radicals, the journalist Marat, who, like Danton, was about to enter the Convention as a deputy, openly associated himself with a justification of the killings by signing a letter issued by the Commune’s surveillance committee on September 3. The people, the committee claimed, had decided that the executions were “acts of justice that seemed indispensable to them in order to deter, through the use of terror, these legions of traitors… at a moment when it was about to march out to meet the enemy.… We will not leave behind us brigands who will slaughter our children and our women.”41

Among the many consequences of the September massacres was the creation of an unbridgeable gap of distrust among the revolutionary radicals who had collaborated during the summer of 1792 in order to remove the king from the throne. It was not the massacres themselves that completed the rupture between Brissot and the Girondins, on the one hand, and Robespierre and the more radical Jacobins, on the other: neither group had a hand in organizing the killings, but neither rushed to condemn them once they started. On September 3, Brissot’s close ally Roland, the minister of the interior, complained that the Parisian militants were disrupting his efforts to maintain order, but he referred to the previous day’s massacre as an event “that we should perhaps leave behind a veil.” He added, “I know that the people, terrible in its vengeance, still is exercising a kind of justice.” The only action he demanded from the Legislative Assembly was a declaration that it had been powerless to stop the killings.42

Within a few hours, however, Roland and Brissot were almost swept up in the bloodshed themselves. Commune officials issued arrest warrants for them that could have resulted in their being sent to one of the prisons where inmates were being killed. At the Commune assembly, Robespierre called Brissot and other leading members of the Legislative Assembly “perfidious intriguers working with the armed enemy powers against French liberty.” Madame Roland had no doubt that the arrest warrants had been inspired by their political rivals. “We are under the knife of Robespierre and Marat,” she wrote to a friend. “Danton is, behind the scenes, the leader of this gang.”43 No evidence has ever shown that Robespierre, Marat, or Danton were responsible for the arrest warrants, but they had certainly come to doubt the loyalty of Brissot and his allies as a result of their wavering behavior in the last days before the August 10 uprising. The Brissotins, however, were convinced that their rivals in the revolutionary movement had tried to take advantage of the massacres to have their leaders killed. There was now little possibility of the two groups working together.

The prison massacres shocked contemporaries at the time and must necessarily trouble all those who think that the contribution the French Revolution made to modern ideas of liberty and equality puts the movement in a different category from those of the Nazis, the communists, and the instigators of recent genocides. The September massacres stand out from most other episodes of violence in the Revolution both for the large number of victims and for their one-sided nature. The casualties during the fighting on August 10 may have equaled those in the massacres, but August 10 was a battle between two armed groups in which both sides thought they were defending their lives, whereas the victims of the septembriseurs had no chance to resist. The massacres are also particularly troubling because of the way in which they were integrated into the revolutionary narrative, even by figures who were in principle opposed to arbitrary violence. The killers were never identified or punished, and most of the revolutionary leaders agreed that it was best to cover the episode with a “veil of silence” rather than disrupt efforts to ward off the foreign invasion. The idealistic Jean-Marie Goujon said nothing about the similar massacre in his town of Versailles.