14

THE REVOLUTION ON THE BRINK

June–December 1793

EVEN FOR A POPULATION INURED TO CHAOS AFTER FOUR YEARS OF REVOLUTION, the summer and fall of 1793 were times of extraordinary upheaval. Enemy armies threatened the country from all directions, and within its borders, new provincial uprisings against the radical Montagnards joined the royalist rebellion in the west. In the capital, male and female activists demanded drastic measures to help the common people survive economically, challenging the authority of both the National Convention and the Commune. Across the Atlantic, many of the country’s prized colonies threatened to slip out of its control, and in France’s most valuable overseas possession, Saint-Domingue, revolutionary officials took the extraordinary step of offering freedom to the black slaves, overturning the institution of slavery so central to all the European colonial empires. Both in France and abroad, many doubted that the movement that had begun with such high hopes in 1789 could possibly survive. In the midst of this hurricane of conflicts, an improvised set of institutions took shape that would enable revolutionary leaders to carry out an unprecedented mobilization of the country’s resources and fight off the threats facing it. The Revolution that emerged from the cauldron of mid-1793, however, was a very different kind of movement than the one that had begun in 1789.

The explosion that had been building up ever since the execution of Louis XVI finally erupted in Paris on the night of May 31, 1793. With neither the Girondin nor the Montagnard faction in the Convention able to achieve solid control of the national legislature, “both sides began to look for victory by mobilizing support from outside,” wrote the deputy René Levasseur. The Girondins counted on their backers in the provinces; in early May, Vergniaud, their leading orator, told his constituents in Bordeaux, “There is not a moment to lose. If you show real energy, you will compel the men who are provoking a civil war to back down.”1 In response, the Montagnards put their fate in the hands of the popular movement in the capital. The journée of May 31 to June 2, 1793, began by following the script of the uprising of August 10, 1792. In the middle of the night of May 30, members of the insurrectionary committee that had been meeting since mid-March to plot against the Girondins declared themselves the representatives of the sovereign people. They installed a dependable military commander, François Hanriot, as head of the military units of the Paris sections, announced that the assemblies of the sections would now meet in continuous, permanent sessions, ordered the sounding of the tocsin to assemble the troops, and informed the Commune that they were calling for an insurrection.

On August 10, the main target of the uprising had been the king, who was blamed for betraying the country and the war effort. The insurrection of May 31 was aimed at the Convention, whose members had been elected by the people. This assault on the deputies risked leaving France with no recognized government at all. For this reason, and because they feared another massacre like the one that had taken place the previous September, even radicals who had supported the August journée initially hesitated to endorse the insurrection. These men included Pierre Gaspard “Anaxagoras” Chaumette, the principal official of the Paris municipal government, and Hébert, the sans-culottes’ favorite journalist. “I witnessed Chaumette… shout, cry, tear his hair, and make the most violent efforts to convince [us] that the Comité central was effecting the counter-revolution,” one of the Evêché committee members later testified.2

Once the Commune decided that it had no choice but to back the movement, the problem was to put enough pressure on the Convention to force the ouster of the Girondin leaders without completely destroying the national legislature’s authority. Added to the original insurrectionary committee, representatives of the Commune tempered the movement’s list of demands, which had originally called for drastic economic measures meant to benefit the poor, the creation of a revolutionary army to force rural farmers to deliver grain at an affordable price, and a complete purge of government personnel.

Early on May 31, armed sans-culottes surrounded the Tuileries Palace, now the Convention’s meeting place. Some of them pushed their way into the assembly hall, where they mingled with the deputies in a scene of complete confusion. The Convention still hesitated to expel any of its own members, and as the first day of the insurrection came to an end, the militants who had launched it were badly frustrated. During the night, the insurrectionary committee had acted on its own to arrest Madame Roland, whom they viewed as the symbol of the Girondins, and made sure that Hanriot’s armed men would return to surround the Convention again. The day of June 1 brought no resolution: the Convention still refused to bow to the demonstrators’ demands. On June 2, a Sunday, crowds even larger than those of the previous two days gathered in the center of Paris. “All the deputies were surrounded to the point where they could not leave,” a Jacobin member reported; the deputy Grégoire had to allow four armed men to escort him to the latrines.3 The sense of urgency was heightened by the arrival of reports from Lyon, where anti-Montagnard forces had taken control of the city’s sections on May 29; in a reversal of the situation in Paris, they had used them to overthrow the radical city government.

In the name of the Committee of Public Safety, the centrist deputy Barère appealed to the Girondin leaders to voluntarily step down as a patriotic gesture to end the crisis. A few of the Girondins gave up their seats, but others indignantly refused to yield to the pressure of the crowd. The Convention passed a decree ordering the withdrawal of the armed forces surrounding it; Hanriot responded by threatening an artillery bombardment. This was too much even for many of the Montagnard deputies. Danton protested that “the majesty of the Convention had been outraged.” Led by the Convention’s president, Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles, the majority of the deputies marched out the door to confront the sans-culottes. At each entry to the Tuileries grounds, the result was the same: Hérault ordered the armed crowd to let the deputies pass, but the militants refused. When he confronted Hanriot directly, according to a newspaper account, the general “backed his horse up a few paces, raised his saber… and uttered the order, ‘To arms, cannoneers, to your guns.’” Then “the artillerymen lit their fuses, the cavalrymen raised their sabers, the infantry pointed their guns at the Convention.”4

Recognizing that they were at the mercy of the armed crowd surrounding them, the deputies reassembled in their hall, where the Montagnard leaders insisted that they yield to the will of the people. Marat, who had been denouncing the Girondins for years, now had the chance to personally edit the list of those to be expelled from the Convention and arrested. In the end, it included twenty-nine deputies and the ministers Pierre Lebrun and Étienne Clavière. There was great confusion about who was responsible for carrying out the measures against the Girondins; most of them were able to go into hiding or escape from Paris.

The Girondins’ defeat on June 2 ended the violent conflict within the Convention that had threatened to paralyze the revolutionary government, but there was no certainty that the rest of the country would follow the capital’s lead. The Montagnard deputies in the Convention, the majority of the Jacobin Club, and the authorities of the Paris Commune, who were all eager to see Brissot, Roland, and their supporters finally ousted, had been willing to go along with the insurrection movement, but none of these groups intended to cede their own power to the militants who had launched it.

Among those who were most confused by the situation were the group of antiracist activists who had been pushing the Convention to take a more radical position against slavery and to send a military unit of free men of color to fight against the British and Spanish in the colonies. In March 1793, the former Saint-Domingue plantation owner Claude Milscent had become the first to call for the immediate and unconditional abolition of slavery. In the newspaper of the Cercle social, he wrote that it was no longer possible to “defend two such contradictory constitutions, and fight ceaselessly on the one hand against slavery and on the other to keep it.”5 Julien Raimond pushed for the creation of an “American Legion,” to be commanded by the black composer Joseph Boulogne, chevalier de Saint-Georges. On June 3, immediately after the defeat of the Girondins, the Commune leader Chaumette, an ardent abolitionist, and Jeannette Odo, an elderly woman of color, led a delegation from the group and appeared at the Jacobin Club. Odo was supposedly 114 years old, and her appearance set off a round of applause. However, because their cause had long been supported by Brissot, Robespierre denounced them, and when they asked to address the Convention the next day, their request was rejected.

Of greater concern to the Montagnards who now controlled the Convention was the reaction to the journée in the provinces. Moderates sympathetic to the Girondins and hostile to the pretensions of the Paris sans-culottes dominated the administrations of many of the departments. Forty-seven of the departments sent letters to the Convention denouncing the journée of May 31–June 2; only thirty-four others either applauded the events in Paris or said nothing at all. In most cases, the anti-Montagnard departments did little else to respond to the events. Local movements against Parisian radicalism had already taken control of two key cities, Lyon and Marseille, however, and even before the uprising, Caen, the capital of the Calvados department in Normandy, had issued a call to create an armed force to protect the moderate deputies in Paris.

On June 9, a general assembly of delegates from the sections of Caen declared the city in insurrection against the Convention; they then sent messengers to incite other parts of Normandy and Brittany to join the movement. In Bordeaux, the capital of the department of Gironde that had given the Girondin faction its name, news of the measures against the deputies led to the formation of a Popular Commission that took over governmental powers and announced its determination to resist the Montagnards. In the Mediterranean island of Corsica, the young Napoleon Bonaparte was among those who had to decide whether to back the Jacobin central government or to join a revolt against it. The revolt was led by Pasquale Paoli, who was determined to declare the island’s autonomy. Bonaparte and his family sided with the Convention’s representative in the island. They were forced to flee to the mainland as Paoli not only rejected that body’s authority but put Corsica under the protection of the king of England.

The outbreak of resistance in the provinces hardened the Montagnards’ attitude toward the Girondins. The Montagnards now denounced their opponents as fédéralistes (federalists) bent on breaking up the “one and indivisible” republic proclaimed after the overthrow of the monarchy. Federalism—the idea that a country could be made up of relatively autonomous local units loosely bound together—was the political system adopted by the United States: there, the constitution of 1787 had created a central federal government that left important powers to the states. In France, however, the idea suggested a retreat to the old regime, where the provinces had had different laws, and this, the revolutionaries believed, would undermine the common national identity they wanted to promote. In the midst of a foreign war and the other crises facing the country, weakening the powers of the central government also seemed like a recipe for disaster.

Above all, the participants in the provincial revolts denounced the excessive influence of the Paris population, the sections and clubs of the capital, on the Convention. They called for the abolition of the Revolutionary Tribunal and the Committee of Public Safety, the improvised institutions that had strengthened central authority, and for the recall of the deputies sent “on mission” from Paris. They insisted that they were not in rebellion against the Convention, but could only recognize its authority when it had “recovered its liberty, its integrity,” by readmitting the expelled deputies and renouncing “the laws that it did not pass freely.” If the Convention deputies were too divided to accomplish their tasks, the rebels told them, they should call for new elections.6 There was nothing obviously “federalist” about this program; but there was also no hint of how it could be carried out in the circumstances facing France in June 1793.

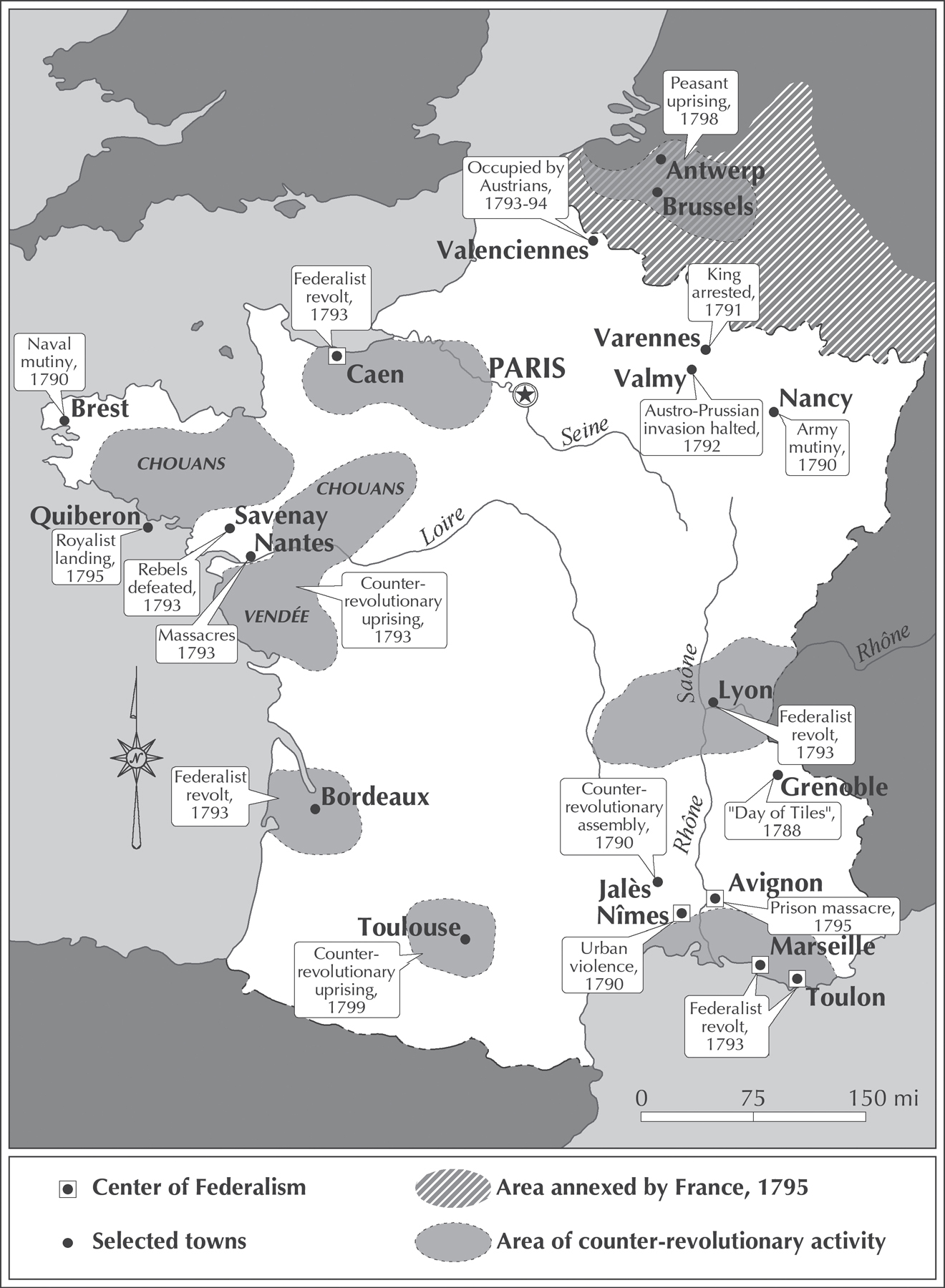

THE REVOLUTION IN THE PROVINCES: Paris dominated the history of the French Revolution, but many important events, from the Great Fear of 1789 to counterrevolutionary uprisings, occurred far away from the capital, and even in France’s overseas colonies, as this map shows. The ability of the revolutionary government to establish control over the provinces was decisive in determining the Revolution’s outcome. Credit: Richard Gilbreath.

Initially at least, the so-called federalist movements were led by middle-class political figures who had supported the Revolution and endorsed the creation of the republic. Things would soon change in some areas as the military situation became increasingly desperate for the rebel leaders, who found themselves forced to ally with royalists, and even, in the Mediterranean port city of Toulon, with foreign forces. From the outset, the federalists often had the backing of urban artisans and shopkeepers, the same milieus from which the radical sans-culottes of Paris were drawn. In Lyon, for example, where the Revolution had disrupted demand for the silk cloth that was the city’s main product, weavers often sided with the merchants in longing for an end to upheaval, rather than sympathizing with attacks on the rich. Unlike the revolt in the Vendée, the federalist movements had little peasant backing: while their participants included some members of the constitutional clergy, as well as some Protestants, such as Rabaut Saint-Étienne, they were not willing to make common cause with the refractory clergy and their supporters. The Vendée rebellion was still spreading even as the federalist protests unfolded, but the two movements had too little in common to allow them to join in fighting the national government. In early June, even as residents of the Breton port city of Nantes were expressing their opposition to the recent journée in Paris, they were also desperately fighting off a Vendean assault.

While the provincial centers of opposition to the Convention tried to organize themselves, leaders in other cities debated their own course. In Perpignan, the local newspaper denounced the “fatal day of May 31”; but how, the editor exclaimed, was it possible to “send forces marching on Paris! Recall our battalions from the frontiers! When these frontiers are menaced or ravaged by the numerous phalanges of foreign tyrants.”7 Meanwhile, in Paris, Montagnard deputies moved swiftly to exploit their control of the national legislature. That control was not yet complete: many Girondin supporters remained in the assembly, where they repeatedly protested that important decisions could not be taken when so many departments were not fully represented, because their deputies had been arrested. By June 19, seventy-five deputies had signed a petition protesting the arrest of their colleagues. To assure support, the Montagnard majority quickly passed a series of laws meant to show their concern for the poor. These included measures to put land confiscated from émigrés up for sale in small lots so that peasants could bid on it; a law proposing the parceling out of village common lands so that all peasants would own at least a small plot; an expansion of welfare for the indigent; and an emergency tax on the rich.

As Danton’s friend Pierre Philippeaux put it, “the surest means of calming the agitated departments” was to complete work on the constitution, whose provisions had been debated at intervals since the introduction of Condorcet’s draft in February. A new constitutional committee produced a draft in just a week. Hérault de Séchelles, spokesman for the committee, hailed the proposal as “one of the most popular [constitutions] that has ever existed.” Nevertheless, the document ignored most of the genuinely radical and utopian ideas that deputies had put forward during the preceding months. Jean-François Barailon proposed allowing single women to vote; moreover, he thought that since all citizens were “equal in fact and in rights, we ought to all be dressed the same,” in a “truly national costume.” Jacques-Nicolas Billaud-Varenne, a radical Montagnard who would wind up on the Committee of Public Safety, denounced the evils of economic inequality and proposed to reduce it by limiting the amount of land that any one individual could own; he also wanted to impose a heavy tax on inheritances and redistribute wealth to poorer citizens.8

The 1793 constitution largely incorporated the declaration of rights that Robespierre had proposed in April, with its promise of a right to work. Equality, mentioned but not defined in the 1789 declaration, now got an article of its own and took precedence over liberty. In contrast to the elaborate electoral procedures that Condorcet had proposed in his effort to overcome the mathematical difficulties inherent in voting systems, the new system would be simple: instead of sending delegates to electoral assemblies as they had in the elections of 1791 and 1792, voters would choose representatives through direct elections in single-member districts. Originally, the constitutional draft proposed that every law be submitted to a popular vote; this was amended to provide that laws would be presumed to be approved unless primary assemblies in more than half the departments objected to them. Disagreement surfaced briefly about a provision saying the nation would never make peace with an enemy whose forces were occupying French territory. Fearing that this stipulation might commit the country to dragging on hopeless conflicts, the deputy Louis-Sébastien Mercier asked whether France had made a “pact with victory.” A Montagnard, Claude Basire, shot back, “We have made a pact with death,” an example of the exaggerated patriotic rhetoric that was becoming a hallmark of this new phase of the Revolution.9

To the Montagnards, the new constitution embodied the ideals of democracy, republicanism, and national unity. All vestiges of the monarchy were completely effaced, and the once-mighty ministers whose “despotism” the revolutionaries had denounced were demoted to mere “chief agents of the administration” who were not to have “any personal authority.” Many moderate deputies voted for the Constitution of 1793, as one of them later wrote, hoping that it would end “the anarchy and the disregard for the laws” in France by “at least establishing and fixing a form of government.”10 As the Convention had promised in its opening session, the constitution was put to a vote in local assemblies all over the country, even in areas where the federalist movements were resisting the national government. Given the chaotic conditions in much of the country, electoral participation was surprisingly high, above the levels in the legislative elections of 1791 and 1792, and discussions about the document were often animated. With 1,801,918 votes cast in favor and only 11,610 opposed, the new constitution could claim a stronger popular endorsement than any of the other government charters drawn up during the revolutionary decade.

The Paris radicals who had played such a central role in the insurrection of May 31–June 2, 1793, remained dissatisfied, however. The Montagnards had ignored many of their key demands, including the immediate trial and punishment of the Girondins, the imposition of price controls to force down the price of bread, and the establishment of a revolutionary army of sans-culottes to pressure farmers into bringing out the grain reserves that the militants were sure they were hoarding. On June 25, one day after the Convention approved the new constitution, Jacques Roux delivered a furious diatribe that fully justified his reputation as one of the agitators known as the “Enragés”: “You have just finished writing a constitution that you are going to submit to a vote of the people. But did you include a ban against speculation in it? No! Did you announce punishments for hoarders and monopolists? No! All right: we tell you that you haven’t finished the job,” he roared.11 Roux’s demands were too extreme even for the firebreathing “Père Duchêne”; worried that the Enragés were cutting into his own popular support, Hébert prevented the Commune assembly from criticizing the constitution.

The completion of the constitution coincided with intensified conflict within the country. On June 24, after more than half of the targeted Girondin deputies had escaped from Paris, the Convention jailed the remaining members of the group. On June 28, delegates from ten departments in Normandy and Brittany gathered in Caen to discuss organizing a march on Paris. By this time, however, it was already clear that few men were ready to volunteer for such an expedition. In Bordeaux, efforts to create an insurrectionary army also fell flat. Meanwhile, the Convention was rallying its forces to crush the uprisings. On July 8, the Montagnard Saint-Just delivered a vehement indictment of the Girondins, accusing them of “a conspiracy to reestablish tyranny and the old constitution” by putting Louis XVI’s son on the throne. Five days later, on July 13, the small military force the federalists had assembled in Normandy was easily dispersed, effectively ending the one rebellion that directly threatened Paris. “They had calculated according to the initial movement of excitement, and they didn’t seize it,” Pétion, one of the deputies expelled from the Convention who had taken refuge in Normandy, wrote dejectedly.12 Even as the federalist rebellion in the northwest was crumbling, however, resistance elsewhere was becoming more serious. On July 12, Lyon officially declared itself at war with the Convention. Fortunately for the Montagnards, deputies on mission in the area and local military commanders prevented the Lyonnais from linking up with the rebels in Marseille, who had sent troops to occupy a number of other cities in their region.

On the same day that the Norman federalist army was defeated, Paris was jolted by an assassination that struck fear into the hearts of all supporters of the Revolution. Charlotte Corday, a young noblewoman from Normandy who was sympathetic to the federalist cause, talked her way into the apartment of the journalist and deputy Marat, the “Friend of the People,” by passing him a note claiming that she could give him important information about the federalist conspiracy in her home region. She found the ailing Marat sitting in his bathtub, trying to ease the pain from a skin disease, and quickly stabbed him to death. Corday made no effort to escape. She admitted her sympathy for the Girondins but insisted that she had acted solely on her own initiative. She told her interrogators, “I knew he was ruining France. I killed one man to save a hundred thousand.” The calm courage she showed at her trial impressed onlookers. Condemned to death, “she wrote to her family and asked for a painter, saying that she would certainly be celebrated in history,” one journalist wrote.13

The assassination of Marat set off a theatrical outpouring of grief in Paris, even among politicians who had criticized his extremism. The artist Jacques-Louis David, now a Montagnard deputy, quickly worked out the design of the classic painting in which he managed to imbue the figure of Marat slumped in his bathtub with a timeless dignity. David also oversaw an elaborate Roman-style funeral meant to apotheosize his friend, but the solemnity of the event was undermined by the terrible stench emanating from the journalist’s body, which putrefied quickly in the searing summer heat. That a woman “had shown the example to men,” as the Girondin Pétion, who had met Corday in Caen, put it, stoked accusations that women could not be trusted; the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women tried to counter such attacks by insisting on playing a major role at Marat’s funeral. The Cordeliers Club, where Marat had spoken so often, had his heart, “the precious remains of a god,” conserved in an urn that was hung from the rafters of its meeting room.

Whatever their true feelings about Marat, supporters of the Revolution saw Corday’s crime as evidence that hidden enemies surrounded them. Robespierre insisted that “the honor of a dagger is also reserved for me.” That the assassin had been a young and beautiful woman struck one journalist as particularly threatening: “No one looked less like a creature thirsty for blood,” he wrote.14 News that the Lyon federalists had executed their local Montagnard radical Chalier on July 16, 1793, added to the sense that no patriot’s life was safe. Together with the deputy Michel Lepeletier, who had been assassinated at the time of Louis XVI’s trial, Marat and Chalier were elevated to the status of martyrs whose blood demanded to be avenged.

Marat’s assassination coincided with a shift of power in the Convention. Since April, the assembly had relied on the Committee of Public Safety to give overall direction to the government. At first, Danton, the popular tribune, was the most visible member of the committee, but by July it was evident that he and his supporters lacked a clear policy to deal with the crises facing the country. On July 10, the Convention ousted Danton from the committee, leaving it without a dominating personality. That situation changed on July 27, when the assembly added Robespierre to the group. Although he already had a national reputation dating back to his defiant defense of democratic principles in the National Assembly, Robespierre had never had any direct governmental responsibility. For the next year, he would be the central figure in the revolutionary government, and history would remember him as the most visible leader in the Revolution’s most radical phase, responsible both for the successful defense of the movement and the extreme methods it used to defeat its opponents. Although he had a personal authority that none of the other committee members could match, Robespierre was never a revolutionary dictator in the mold of V. I. Lenin or Mao Tse-tung. Throughout Robespierre’s short time as the most prominent participant in the revolutionary government, he shared power with the other members of the Committee of Public Safety. His colleagues never hesitated to argue with him, and on some crucial issues, he was in the minority within the group.

In the struggle for power in the summer of 1793, Robespierre’s guiding principle was that the authority of the Convention needed to be maintained, even as he warned that there were still disloyal members among the deputies. He denounced agitators who stirred up the anger of the populace about food prices, accusing them of trying to provoke another round of attacks on shops “by the people, or really by criminals disguised in the clothing of people.” He also singled out the Enragé Jacques Roux, asking whether “this priest, who in concert with the Austrians denounces the best patriots, can have pure views or legitimate intentions.” In his view, leadership needed to be in the hands of “men who love the people without saying so, who work tirelessly for its good without boasting.” Yet he shared with the sans-culotte militants a conviction that the Revolution was threatened by conspiracies of all sorts. At times, he called for the dismissal of all the army’s generals as well as the government’s officials. The man who in 1791 had delivered one of the Revolution’s most eloquent defenses of press freedom now exhorted the Jacobins to “fall on all the odious journalists… whose existence becomes more pernicious to society every day.”15

As the summer of 1793 wore on, pressure to find ways to defeat the Revolution’s enemies grew. The Convention tried to shore up rural support for the Revolution by decreeing, on July 17, that peasants would not have to pay any more compensation for abolished feudal privileges, but they had long since stopped making those payments anyway. On July 26, the Convention passed a sweeping decree declaring that “monopoly is a capital crime.”16 The law denounced speculators who hoarded supplies of any of a long list of foodstuffs and raw materials and ordered all those dealing in such goods to register their stocks with local authorities. The measure made almost every economic transaction suspect and empowered government officials and surveillance committees to invade homes, businesses, and peasant barns looking for violations. Even so, the Enragés and much of the population of Paris remained unsatisfied: bread prices did not come down, and the privileges of the rich remained. Suspicions that nobles and relatives of émigrés were contributing to the crippling shortage of hard currency by smuggling gold and silver out of the country added to the sense that enemies of the Revolution were deliberately exacerbating the economic difficulties that weighed on the poor.

The last days of July brought a wave of bad news from the frontiers. Besieged by Prussian forces for four months, the French forces occupying Mainz finally surrendered, ending the effort to spread republican principles to Germany. In northern France, civilians panicked by the Austrian bombardment of the city of Valenciennes forced its garrison to evacuate, allowing the enemy to take a key position on French soil. Suspicion fastened on General Adam Philippe Custine, who had led the French occupation of Mainz before being transferred to command of the army in the north: Robespierre compared him to Dumouriez and accused him of being in the pay of the British. As the chronicler Ruault put it, “in the eyes of the sans-culottes incompetence and treason are more or less the same.” Custine’s trial by the Revolutionary Tribunal dragged on for much of the month of August, intensifying fears about the loyalty of military officers who, like him, came from noble families. Meanwhile, the campaign against the rebels in the Vendée and Brittany was also going poorly. In the Convention, Barère complained that none of the bickering republican commanders there understood how to fight the kind of elusive enemy they were facing: “Your army is like that of a Persian king,” he said. “It has one hundred and sixty baggage wagons, whereas the brigands march with their weapons and a scrap of black bread in their sack.”17

In the face of these setbacks, the Convention tried to recapture the spirit of enthusiasm and unity that were now remembered as the hallmarks of the early stages of the Revolution by taking aim at remaining vestiges of elitism. In addition, they staged a great public festival to celebrate the popular vote in favor of the new constitution. On August 8, 1793, after listening to the artist David denounce the academies that had overseen artistic and scientific endeavors as “monstrous corporations, survivals of the royal and ministerial regime that have been tolerated for too long” (the Jacobin priest Grégoire chimed in by claiming that they had “tried to monopolize glory and guard for themselves the exclusive privilege of talent”), the Convention voted to do away with them. A pamphleteer called for “a sans-culotticized science” and accused the “savants” of the academies, like priests, of “employing a mystical language, to avoid enlightening those they called profane.”18 Even the descendants of the philosophes now found themselves stigmatized as enemies of equality.

The Festival of Republican Unity, on August 10, was David’s most elaborate production. Participants followed an itinerary that took them across the city to perform a series of symbolic rituals. At the Bastille, the Revolution’s birthplace, they drank water that poured from the breasts of a giant statue of a woman representing Nature, the source of liberty and equality. Deputies and public officials were deliberately mixed in the procession with ordinary citizens in their working clothes; the official account of the festival emphasized that “the African, whose face is blackened by the fire of the sun, marched hand in hand with the white man.… [A]ll were equal as men, as citizens, as members of the Sovereign.” In an unprecedented public recognition of the role women had played in the Revolution, an arch of triumph celebrated the heroines of the October Days of 1789. The Convention’s president, Hérault de Séchelles, saluted their achievement, but then reminded them that they now had a more traditional role to play: “Liberty, attacked by all the tyrants,” he said, “needs a people of heroes to defend it; it is up to you to give birth to them!”19

Having honored the conquerors of the Bastille and the heroines of the October Days, the procession moved on to the Place de la Révolution, where a statue of Liberty had been erected on the spot where Louis XVI had been guillotined. Here, Hérault de Séchelles set fire to an assemblage of objects symbolizing the old regime: thrones, crowns, scepters, coats of arms. As the flames roared, three thousand birds were released into the air. The birds bore tricolor ribbons with the message, “We are free! Imitate us!” At the festival’s final site, on the Champ de Mars, participants had to pass under a carpenter’s level suspended from a tricolor ribbon, a Masonic symbol meant as “a visible representation of the social equality that keeps all men on an equal plane.” David had erected a colossal statue of Hercules; the demigod held a bundle of sticks in one hand while preparing to crush a monster under his feet with a club. In case the crowd did not initially grasp the statue’s symbolism, Hérault’s speech explained it to them: “This giant whose powerful hand brings together in a single bundle the departments that make its grandeur and its force is you! This monster whose criminal hand wants to break the bundle and separate what nature has united is federalism!”20

No one could mistake the role that the people were called on to play two weeks later, on August 23, when, to overcome the military crisis, the deputies decreed a levée en masse, that is, a “total mobilization” of the nation’s population and resources. Whereas previous draft calls had affected only men of military age, the levée en masse demanded a universal effort. “The young men shall go to battle; the married men shall forge arms and transport provisions; the women shall make tents and clothes, and shall serve in the hospitals; the children shall turn old linen into lint; the old men shall repair to the public places, to stimulate the courage of the warriors and preach the unity of the Republic and hatred of kings,” the decree said. The measure looked backward to the revolutionaries’ idealized image of the patriotism of the ancient Greeks and Romans, but it also looked forward to the age of total war in the twentieth century. Theoretically meant to raise seven hundred thousand new troops, the levy only produced about two-thirds that number. The many calls for volunteers in the previous two years meant that there were few enthusiastic recruits left to send. In his village, the schoolteacher Delahaye wrote, “there was general desolation at the departure of these poor young men.”21 Nevertheless, the decree effectively conveyed the message that all individual interests were now overridden by the need to defend the country.

The day before the levée en masse was decreed, the Convention’s forces opened their assault on the rebel city of Lyon, the most significant of the remaining federalist strongholds. The city’s population had actually voted to accept the Constitution of 1793, hoping that their action might open the way to a negotiated end of the conflict with the Convention, but the government in Paris was in no mood to make concessions. With no choice but to hope that a foreign invasion might divert the Convention’s forces before the city had to surrender, the leaders of the revolt accepted the support of royalists like Louis François Perrin de Précy, who was named Lyon’s military commander. The presence of royalists among the defenders served the Montagnards’ propaganda interests. As the Convention’s forces tightened the noose around Lyon, the federalist movements south of the city faced drastic choices. Marseille, one of the major centers of resistance in the spring of 1793, surrendered. In Toulon, however, the home base of France’s Mediterranean fleet, moderates and royalists accepted an offer from the British to land troops and help defend the city in exchange for the disarmament of the French warships in the harbor.

Like General Dumouriez’s treason, the surrender of Toulon caused a furious reaction in Paris. The news arrived on September 4, 1793, just after confirmation of another sensational disaster, the destruction of the city of Cap Français, the main port of the Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue. The burning of the city, which caused somewhere between three thousand and ten thousand deaths, resulted in a huge economic loss, as warehouses full of sugar and coffee went up in flames. It was the most extensive incident of urban violence in the entire course of the Revolution. The first reports of the event, which had taken place on June 20, were highly confused. They gave the impression that the two republican civil commissioners sent to the island a year earlier, with the support of the now disgraced Brissot, had staged a colonial version of a federalist revolt. “The national commissioners [Étienne] Polverel and [Léger-Félicité] Sonthonax have usurped a dictatorial authority in the island, and their criminal ambition is the cause of these latest misfortunes,” noted the Montagnard Committee of Public Safety spokesman André Jeanbon Saint-André, speaking to the Convention on September 3.22 He said nothing about the truly revolutionary step the commissioners had taken. On the night of June 20, after the commissioners and their free colored defenders had nearly been overwhelmed by their opponents in Cap Français, Polverel and Sonthonax had offered immediate freedom to any black slaves who would take up arms to support them.

Up until this moment, the French authorities in Saint-Domingue had been doing their best to defeat the black insurgents who had risen up in August 1791; many of the same men had enrolled themselves in the Spanish army when that country joined the war against France in early 1793. When they arrived in the colony in September 1792, Polverel and Sonthonax had publicly sworn that they would resign their posts rather than obey any decree from France ordering the abolition of slavery. Nevertheless, both men were personally critical of slavery; in September 1790, Sonthonax, the younger and more outspoken of the two, had written an anonymous article in the Révolutions de Paris predicting that “the day will come—and the day is not too far off—when you will see a curly-haired African, relying only on his virtue and good sense, coming to participate in the legislative process in the midst of our national assemblies.”23 The emergency they found themselves facing on June 20 gave the commissioners a justification for acting in accordance with their personal convictions, although they had no assurance that the Convention in Paris would approve of their decision.

The commissioners’ initial offer was limited to men capable of joining the army. But they soon realized that recruiting loyal black soldiers required extending the scope of emancipation, first to the wives and children of those men who volunteered, and then, by the end of August 1793, to all blacks in the colony. Furthermore, the commissioners’ concept of emancipation was constrained by their determination to maintain the plantation system that made the colony so valuable to France. Ignoring one idealistic white colonist who thought that, as long as plantation owners’ property rights over their slaves were going to be ended, the moment had come to create a society based on “the community of goods among all the individuals,” they drew up plans under which blacks would be legally free but still obligated to work in the sugar fields.24

There were thus good reasons for many blacks to remain suspicious of the French officials’ intentions. Toussaint Louverture, who by this time was serving as a general in the Spanish army, condemned the French republicans for executing the king and persecuting the Church and indignantly rejected their emancipation offer. “You try to make us believe that Liberty is a benefit that we will enjoy if we submit ourselves to order,” he wrote to Sonthonax and Polverel, “but as long as God gives us the force and the means, we will acquire another Liberty, different from that which you tyrants pretend to impose on us.”25 Persuaded by his Spanish allies that revolutionary France was about to be overrun by its foes, Louverture and the other black leaders saw no point in accepting promises that might never be fulfilled. Nevertheless, the crisis of June 20, 1793, which culminated in the burning of Cap Français and the flight of the majority of the colony’s white population, opened the largest breach in the system of slavery in the history of the Americas. Within a few months, not only would Louverture change sides, becoming one of the strongest defenders of the measures Sonthonax and Polverel had taken, but the Convention would extend the abolition of slavery to the rest of the French Empire.

The destruction of Cap Français had an immediate impact in the United States. Refugees fleeing the island flooded into the port cities of Norfolk, Baltimore, and Philadelphia in early July. The young American republic was revolutionary France’s only ally, but the efforts of the French emissary Edmond-Charles Genêt, one of Brissot’s diplomatic nominations, to pull the United States into conflict with Britain and Spain were putting great strain on the relationship. When Genêt first arrived in the spring of 1793, “Democratic Republican” supporters of Thomas Jefferson welcomed him ecstatically, seeing the French Revolution as a logical extension of the American movement. The Federalists, who followed President George Washington, however, warned against allowing republican enthusiasm to drag the country into wars for a “foreign interest.” The angry clashes over Genêt’s mission marked the creation of America’s first political parties. The arrival of the Saint-Domingue refugees, some of whom brought black slaves or free colored mistresses with them, raised fears that “French Negroes” would incite slave rebellions. By the end of July, Washington’s cabinet had agreed to demand that the French recall Genêt. Ironically, in Paris, the Committee of Public Safety had already decided to dismiss him, not because he had alienated the American government but because he was a Brissotin. The Genêt affair marked the beginning of a separation between the world’s only two democratic republics and left the French feeling that they were truly isolated in a hostile world.

Combined with the catastrophic news from Toulon, the reports of the upheaval in Saint-Domingue provoked yet another popular insurrection against the Convention on September 5, 1793. The organizers of this journée were not the obscure section militants who had started the movement of May 31, but rather the leaders of the Commune, Chaumette and Hébert, and radical members of the Jacobin Club, such as the deputies Billaud-Varenne and Collot d’Herbois, who were determined to force the Committee of Public Safety to adopt more extreme measures to save the country. The demonstrators bore placards calling for “war on tyrants, hoarders and aristocrats,” and their slogan was to “make terror the order of the day.” Their most concrete demand was one that had been on the populist agenda since the spring: the formation of a revolutionary army of sans-culottes to comb the countryside, rooting out opposition and hunting for grain supplies. Billaud-Varenne, for his part, suggested a new committee to replace the Committee of Public Safety and achieve what it had not, the extermination of the Revolution’s enemies.26

The members of the Committee of Public Safety had grave reservations about creating a revolutionary army. Coordinating the fourteen separate armies already in the field and keeping them from competing with each other for desperately needed supplies was already stretching the government’s resources to the limit. The revolutionary army would be under the control of populist allies of Hébert, who had little respect for the Committee or the Convention. Unleashing armed bands of militants in the countryside threatened to spread further chaos and to alienate the rural population. Nevertheless, the popular pressure was impossible to resist. In the Convention, Danton once again showed his talent for improvisation. He moved to create a revolutionary army, but to put the Committee of Public Safety in charge of organizing it. At the same time, however, the ability of the Paris sections to mobilize against the Convention would be reined in by ending their right to remain in permanent session, which allowed them to constantly stir up public opinion, and limiting them to just two short meetings per week. In an apparent gesture to the sans-culottes, Danton proposed that workers and artisans who attended the sections be paid for coming. It was a clever maneuver because the participants would have an interest in getting their money, which would be at risk if they disrupted the regular workings of the government. To ward off criticism of the Committee of Public Safety, the deputies added the two firebrands Billaud-Varenne and Collot d’Herbois to its membership.

As the crowd dispersed, few recognized that, thanks to Danton, the Convention had eluded the militants’ demand to officially declare “terror the order of the day,” a step that would have committed the government to satisfying the radicals’ call for a wave of repression unrestrained by the law. Nevertheless, the journée of September 5 set the stage for a sharp intensification of measures aimed at real and imagined enemies of the Revolution and a dramatic expansion in the power of the central government. Terror—the swift punishment of opponents and the demand for unquestioning obedience to official decrees—was an openly acknowledged means of carrying out these decrees. The idea that the law should inspire terror in the souls of those tempted to violate it had a long history in the old regime. Montesquieu, however, had given the word a negative connotation, identifying it as the principle of despotic regimes. In the first years of the Revolution, Marat had been almost alone in praising popular violence as a way of creating “this mood of terror that is healthy and so indispensable to achieve the great work of the constitution.”27 By mid-1792, many revolutionaries had come to share the idea that the Revolution’s enemies needed to be intimidated through terror; both the Girondin Vergniaud and the Montagnard Danton spoke of making the royal court experience the fear it had long inspired in the people.

What was new in the late summer of 1793 was the concept of terror as a systematic method not just to defend the Revolution, but to achieve its positive aims. “Yes, terror is on the order of the day, and should be for the egoists, for the federalists, for the rich who have no pity, for the ambitious who are dishonest, for the shameless intriguer, for the coward disloyal to the country, for all those who do not feel the dignity attached to the title of a free man, the pure republican.… No compromise, France must be either entirely free or perish completely, and all methods are justified to uphold such an admirable cause,” wrote the Révolutions de Paris.28 The revolutionaries did not use the phrase le règne de la terreur (reign of terror), which, along with the word terroriste (terrorist), was invented by opponents of Robespierre after his overthrow in 1794, to discredit the system it described. Nevertheless, these terms are undeniably accurate as descriptions of the policies followed in late 1793 and the first half of 1794 by the men who held power in France for the ten months that followed the September journée. Convinced that the survival of liberty and equality in the world depended on the survival of the French Republic, and fearful that they themselves would not survive if the Revolution was defeated, they fully intended to instill fear—not just in their enemies, but in the citizenry at large.

In February 1794, when the scope of this policy had become clear, Robespierre unhesitatingly defended it, telling his listeners that without terror, “virtue is impotent.” What justified the terror of the Revolution in his eyes—and what made it different from the uncontrolled violence of the common people—was that it was an instrument of justice carried out through the law, not simply a weapon of the strong deployed to overawe the weak. To its victims, this insistence that revolutionary terror was a form of law and justice was what made it particularly objectionable. From her prison cell, Madame Roland, long one of the Revolution’s most devoted supporters, denounced “the rule of these hypocrites who, always dressed in the mask of justice, always speaking the language of the law, have set up a tribunal to carry out their vengeance.”29 Given her situation, she could hardly have appreciated how sincerely men like Robespierre believed that what they were doing was necessary and justified. But it was the intensity of that conviction that allowed Robespierre and many other participants in the Revolution to tolerate the all-too-real abuses of power that Madame Roland identified so astutely.

After the journée of September 5, 1793, it was clear that, in spite of the elaborate celebration of the new constitution a month earlier, there was not going to be any move to actually put it into effect by holding elections for a new legislature. Robespierre denounced the “insidious proposition” of replacing the Convention’s “purified members” with “envoys of Pitt and Cobourg,” referring to the foreign enemies of the Revolution.30 Until the war was won and the security of the country assured, the Convention elected in 1792 would continue to govern the country. Moreover, until the Convention decided otherwise, the Committee of Public Safety, now clearly dominated by the most radical Montagnards, would be the center of policy making. The committee ruled from September 1793 to July 1794. The only body that shared authority with it was the Committee of General Security, which oversaw the police and the Revolutionary Tribunal.

The Convention moved swiftly to give these two “committees of government” broadened powers. On September 17, 1793, the “law of suspects” authorized the arrest of “those who, by their conduct, associations, talk, or writings have shown themselves partisans of tyranny or federalism and enemies of liberty.” In addition to this wide and vague definition of suspects, the law targeted a number of specific groups: anyone who could not show that they earned their living honestly, any former public officials who had been suspended or dismissed from their posts, all relatives of émigrés who had not “steadily manifested their devotion to the Revolution,” and anyone who had emigrated from France in the early years of the Revolution, even if they had returned before the deadline set by the law passed in 1792. The surveillance committees created in March 1793 were charged with carrying out the law. In Paris, the Commune issued a list of “characteristics that render people suspect,” including “those who speak cryptically of the misfortunes of the Republic, show pity for the people and are always ready to spread bad news with apparent sorrow,… those who affect, in order to appear republican, an excessive austerity and severity,” and “those who not having done anything against liberty, also haven’t done anything for it,” criteria elastic enough to take in anyone. Those who feared arrest tried to look like good patriots by dressing like sans-culottes and subscribing to the Père Duchêne. “The image of the orator smoking his pipe… served as an icon of safety on the dressing tables of the prettiest women, in the studies of the learned, in the salons of the rich and in business offices,” one Parisian later recalled.31

Local authorities were told to establish prisons to hold suspects “until the peace”; those arrested did not necessarily have to be charged or brought to trial. As was customary at the time, prisoners had to pay for their own food and expenses. A former military officer caught up in the dragnet remembered his captors looking him over and deciding, “He’s tall, he looks self-confident, he’s a suspect.” Recounting the incident further, he added: “I object, I invoke the law, justice, no one listens; outbreaks of laughter echo through the vaults.” The guards strip-searched him, took his clothes and valuables, and threw him into a cell with eighty other prisoners. It was “without beds, without chairs, just old mattresses covered with vermin.” Even individuals who were not imprisoned were placed under onerous surveillance. In the small town of Langres, a devout Catholic nun wrote that “around 300 women are obliged, since they are called suspects, to check in at the town hall every day. Age, illness, nothing matters to them.”32 The country of the rights of man had now created a prison system on a scale without precedent in the Western world; by the summer of 1794, half a million men and women had experienced it.

Two weeks later, the Convention embarked on an equally sweeping effort to regulate the country’s economy. Expanding the system of price controls imposed on grain and bread the previous April to a long list of other essential commodities now became a priority. Even as they praised the virtues of the common people, the deputies had come to be deeply suspicious of what one of them called “the greed and the bad faith of the cultivators”; they believed that farmers were not selling their produce at a fair price and that they were too reluctant to accept the Revolution’s depreciated assignats in payment. The law of the general maximum, enacted on September 29, 1793, aimed to stabilize the prices of foodstuffs, textiles, and basic materials for industrial production and to ensure adequate supplies for the armies. Prices of regulated items were set at 1790 levels augmented by a third to account for inflation. The law also set limits on wages, which were to be one and a half times what they had been in 1790. In theory, this amounted to an increase for workers, but only if they could actually find goods in the market at the government-imposed prices. Meanwhile, the law authorized local officials to punish workers and company owners “who refuse[d], without legitimate grounds, to do their usual work.”33 Jean-Marie Goujon had been one of the first to use the word maximum in this way; it had appeared in his letter to the Convention the previous November. He now suddenly found himself elevated to a position of national importance: the Committee of Public Safety appointed him as one of three members of the commission charged with administering price controls throughout the country. Just two years earlier, he had been giving highflown speeches about the Revolution’s love for the common people; now he was entrusted with satisfying their most pressing practical needs.

Together with the law against hoarding and speculation, the law of the maximum drastically limited the freedom of economic enterprise that had been a central aspect of the 1789 revolutionaries’ original concept of rights. Patriotic businessmen at first promised to respect the law. “It has cost me more than 50,000 livres,” one wrote. “I made the sacrifice without effort and without regret, because a crisis in commerce was necessary to stop the ongoing and limitless increase in the most necessary goods.” Cumbersome to administer, the maximum soon spawned a flourishing black market as customers with money tempted suppliers by offering to pay more than the legal price for scarce commodities. Workers pressured employers to pay them more than the official rate. Only the threat that violators would find themselves jailed as suspects or even sent before the Revolutionary Tribunal forced a grudging acceptance of regulations that were often unworkable. In its original form, for example, the law did not take into account the cost of transporting commodities from their place of origin, an omission that discouraged the shipment of goods to distant markets. Much of the work of the revolutionary armies created after the journée of September 5, 1793, consisted of pressuring peasants to sell their crops at the official price and intimidating workers to do their jobs for what they considered inadequate wages, activities that increased the population’s resentment of the Revolution. “The revolutionary army has been badmouthed throughout the countryside,” a police observer wrote. “The peasants, already upset about the price limit, are not at all disposed to let them peacefully enter their homes and seize… the produce they have stored.”34

For all of its defects, however, the law of the maximum did make it possible to keep the urban population fed and the armies supplied through the winter and spring of 1794. The revolutionary government’s threat to punish those who refused to accept assignats stopped the precipitous decline in the paper currency’s value. After falling to less than 30 percent of its nominal value in September 1793, the assignat rose to over 50 percent of that value in December, even as the mass of money in circulation kept rising. With all the other demands they faced, local officials had little time or energy to collect taxes; the vast majority of government revenue came from the ongoing sale of church and émigré properties, which continued at a steady pace throughout the Terror. Since payments were accepted in assignats, the government got much less than full value from these sales, but they provided what the Convention’s fiscal expert Pierre Cambon called “incalculable resources for the conquest of liberty.”35

To give their policies a legal basis, on October 10, 1793, the Convention deputies endorsed a decree presented by the Montagnard Saint-Just, a member of the Committee of Public Safety, declaring that “the provisional government of France is revolutionary until the peace.” “In the circumstances in which the Republic finds itself,” Saint-Just proclaimed, “the constitution cannot be put into effect; it would be turned against itself. It would protect attacks against liberty, because it would not allow the violence necessary to stop them.” The decree consecrated the power of the Committee of Public Safety, giving it the authority to direct ministers and generals. A more detailed decree issued two months later, on December 4, or 14 frimaire Year II, according to the new revolutionary calendar that the Convention had by then adopted, reversed the decentralization of power that had been one of the central features of the revolutionary process. The decree declared that “the National Convention is the sole motive center of the government” and converted elected local officials into “national agents”; they would be responsible for carrying out the laws passed by the Convention as well as orders issued by the Committee of Public Safety.36 What the absolute monarchy had dreamed of possessing through its system of intendants was now available to its revolutionary successor: a national bureaucracy that would, at least in theory, immediately implement the policies of the central government throughout the country. Napoleon would later call the Terror the only serious government France had during the revolutionary decade.

The necessity of winning the war provided the main justification for the rapid expansion of the revolutionary government’s powers. Although the most heated rhetoric of 1793 was directed against the domestic enemies—the federalists and the Vendée rebels—the bulk of the army was still deployed against foreign foes. Fortunately for the French, the invaders showed much less urgency about pursuing their campaigns than the revolutionaries did in fighting them off. After driving the French out of Mainz, the Prussians shifted their attention to their eastern frontier, joining the Russians in a partition of Poland that was meant to end the reform movement there. In the southeast, the Piedmontese fought to regain the province of Savoy that France had annexed a year earlier, and in the south, Spanish forces took a few border fortresses. These fronts were far from Paris, however: the real threat to the republic was in Belgium. Still following the playbook of eighteenth-century warfare, Austrian and British forces moved slowly and cautiously, laying siege to fortified positions rather than seeking to destroy the French armies in the field. In addition, the allies divided their forces, with the British attacking the coastal port of Dunkirk, while the Austrians sent the bulk of their troops to Maubeuge, hundreds of miles away.

In the fall of 1793, the French inflicted significant defeats on both their opponents in the north. On September 6, General Jean-Nicolas Houchard’s victory at Hondschoote broke the siege of Dunkirk. As in their more famous retreat from the same port in 1940, the British had to abandon much of their materiel and leave the conflict on the continent to their allies. Rather than being praised for his victory, Houchard was promptly arrested for not following it up with enough vigor. On November 15, he was guillotined, his fate a warning to other republican generals. Meanwhile, on October 6, General Jean-Baptiste Jourdan defeated the Austrians at Wattignies, forcing them to give up their effort to capture Maubeuge. While the Austrians managed to retreat in good order, their offensive was ended for the year, giving the French precious time to prepare the fresh troops that the levée en masse was producing for future combat.

As military operations wound down for the year, the revolutionaries undertook new campaigns aimed not just at defending the accomplishments of the Revolution but at changing the world. Already at the beginning of August, in the midst of civil war and military calamities, the assembly had applauded a lengthy report presenting a new system of weights and measures, what we now know as the metric system. The new system was derived from nature itself: the meter was defined as one ten-millionth of the meridian, or the distance from the earth’s pole to the equator; the liter was the volume of a cube defined in terms of the meter; and the gram the weight of a specified fraction of a liter of water. The creators of the metric system saw it as universal, a “symbol of the equality and a gauge of the fraternity that should unite all men.” The fact that they had been able to approve the reform in the midst of so many other preoccupations was important to the revolutionaries. “Philosophy will someday be pleased to contemplate… the genius of the sciences and of humanity transcending the storms of revolutions and wars,” the deputies assured themselves.37

Another campaign altered everyday speech by eliminating the distinction between the polite form of address, vous, customarily used to address one’s social superiors, and tu, reserved for addressing intimates, children, and those of inferior rank. A petition to the Convention promised that if tutoiement, the use of the familiar second-person singular form, was made mandatory, “these principles will be a basic demonstration of our equality, since no man, no matter who he is, will be able to think of distinguishing himself by saying ‘tu’ to a sans-culotte.” There were some objections: one journalist worried that men would take advantage of the new usage to claim a familiarity with women that would “tear down the last barrier between the two sexes.”38 Nevertheless, like the replacement of monsieur, a term of respect, with the egalitarian citoyen, the use of tu became commonplace. The drive for equality also underlay the law passed on 12 brumaire Year II, granting illegitimate children equal shares of their parents’ inheritance. This provision was made retroactive to 1789 a few months later, even though it required reopening estates that had been settled for some years. The law of 12 brumaire prohibited paternity suits, on the optimistic assumption that fathers would no longer need to be pressured to recognize their children.

The transition to the revolutionary calendar was more of a challenge than many of the other changes the revolutionaries introduced, because the rhythm of time was so closely tied to religious observance. The plan to introduce a new calendar presented to the Convention by the deputy Gilbert Romme on September 20, 1793, was explicitly meant to show that the world had entered a new era. Romme’s report denounced the Gregorian calendar as the product of “an ignorant and credulous people.” He added, “For eighteen centuries it served to anchor in time the progress of fanaticism, the abasement of nations.”39 The new calendar started the year on September 22, which, by happy coincidence, as Romme pointed out, was a date significant both in nature, marking the fall equinox, and in history, where it commemorated the proclamation of the French Republic in 1792, which was retrospectively declared to be Year I. The year would now be divided into twelve thirty-day months, each with three ten-day weeks, or décades, and days would be divided into ten hours of one hundred minutes each, an idea that never caught on. Among the many advantages of the new calendar, according to its proponents, was that workers would now be idle only one day out of ten instead of one day out of seven, which would supposedly allow them to earn more income. The shift was also meant to wean the population away from regular church attendance, since Sunday would no longer be a day of rest.

Initially, the months, décades, and days were simply numbered. Philippe Fabre d’Eglantine, a deputy who had been a poet and playwright, came up with an elegant scheme that linked the new months to the cycle of the seasons. A common suffix linked the three months of each part of the year, and their names evoked the prevailing weather. Thus the three months of the fall were vendémiaire, the month of the grape harvest, or vendange; brumaire, the month of brumes, or fall fogs; and frimaire, the month of frost. After a winter of nivôse, pluviôse, and ventôse (snow, rain, and wind), French citizens would greet the spring and its months of germinal, when plants sprouted; floréal, when they flowered; and prairial, when they began to ripen. Messidor (named for the harvest) and thermidor (for heat) hailed the maturing crops in the fields that would be ready in fructidor, the month of fruits. The seasons in Fabre’s scheme were those of European France: the newly emancipated black citizens of tropical Saint-Domingue had to adopt months named for cold and snow that did not correspond to their climate. Since the revolutionaries could not alter the fact that nature had made the solar year 365 days long, each year ended with five “sans-culottide days,” plus an additional day in leap years, each of which would be a festival dedicated to a moral virtue that strengthened the republic.

Persuading the population to adopt the revolutionary calendar became one of the revolutionaries’ main preoccupations, an effort that would only end in the Year XIV, when Napoleon decreed a return to the Gregorian calendar. Use of the new dates was mandatory on all legal documents. Enthusiasts for the new calendar saw it not just as a simpler, more rational, and, thanks to Fabre d’Eglantine, more poetic way of keeping track of time, but as a way for citizens to reaffirm their commitment to the republic in acts of everyday life. For the same reason, opponents of the Revolution stuck to the old calendar and especially to the ritual of Sunday observance as a way of demonstrating their hostility to the new regime. The war over the calendar thus became one of the most contested battlegrounds in the revolutionary struggle.

The introduction of the revolutionary calendar coincided with a sudden and intense campaign to dismantle the Catholic Church altogether. For many revolutionary militants, this de-Christianization campaign was the logical culmination of the Enlightenment critique of revealed religion and the revolutionary program of insisting on exclusive loyalty to the nation. Although the Constitution of 1793 had promised freedom of worship, pressure on the Church had been building up throughout the year. Revolutionaries demanded that priests demonstrate their trustworthiness by renouncing their “unnatural” vows of chastity: they should now marry. A law passed in July 1793 forbade bishops from punishing clergy who did so. Local officials closed churches or converted them to “temples of reason” for the staging of civic ceremonies.

Deputies on mission, such as Joseph Fouché, a onetime Oratorian priest sent to the Nièvre who later became Napoleon’s much-feared minister of police, promoted the antireligious policy vigorously. With support from local militants, he closed churches and had signs posted in cemeteries telling mourners “Death is an eternal sleep,” a direct rebuke to the Christian dogma of the eternity of the soul. At the cathedral of Reims, where the kings of France had traditionally been crowned, the deputy Philippe Ruhl destroyed the phial holding the sacred oil, supposedly dating back to the time of Clovis, with which each of them had been anointed. Priests and nuns as well as church buildings became targets. “I ordered all the curés to marry,” one revolutionary commissioner reported. “Some twenty promised to marry within two months, and I have authority to find wives for them.” Over all, some eighteen thousand parish priests, about a third of the total, officially gave up their status during the de-Christianization campaign, and some six thousand married.40

In Paris, the Commune’s procureur, Chaumette, was an equally enthusiastic supporter of de-Christianization. Along with his allies—particularly Hébert, the author of the Père Duchêne, whose influence was at its height—Chaumette organized a series of events to mark what the de-Christianizers saw as their epochal victory over superstition. Escorted by Chaumette, Jean-Baptiste Gobel, the constitutional bishop of Paris, told the Convention that he was abandoning his religious functions. Only Grégoire, who was a longtime Jacobin but also a firmly committed Catholic, had the courage to take a public stand against the tide. “They harass me now to submit an abdication, which they will not get from me,” he announced; in an act of defiance, he continued to wear his ecclesiastical robes to the Convention even after that body had banned them from public places.41

To consolidate what he considered a victory over superstition, Chaumette presided over a hastily organized Festival of Reason staged in the symbolic heart of Paris Catholicism, the expropriated cathedral of Notre Dame. The Père Duchêne gleefully described the scene for its readers: “The pious, male and female, [were] saddened to see their saints ousted from their niches.… In place of that altar or really of that stage for charlatans, a throne had been constructed for liberty. In place of a dead statue, there was a living image of that divinity, a masterpiece of nature… a charming woman, beautiful like the goddess she represented.” After the ceremony, the crowd took their “goddess,” armed with a pike and coiffed with a red liberty bonnet, to the Convention, where she was seated next to the assembly’s president. Meanwhile, in the streets, “the most ludicrous masquerades presented themselves in every quarter,” the Englishwoman Helen Maria Williams wrote. “The revolutionary ladies and the priestesses of Reason had sanctified themselves with the clothing belonging to the Virgin.”42

The de-Christianizers’ violent assault on the Church was not simply an extension of the philosophes’ campaign against organized religion. It also drew energy from the long-standing popular anticlericalism of ordinary men like Jacques Ménétra, who resented the clergy’s privileges and their interference with ordinary people’s lives. Customary forms of mockery that had been used to ridicule cuckolded husbands and other violators of community norms, such as being promenaded through town on the back of an ass, were now turned on the Church. In the department of Loir-and-Cher, a cart filled with “the remnants of royalism and superstition” was “pulled along by a donkey dressed in a surplice and neckband, and bearing the inscription, ‘I am more useful than a king.’” After attending a Festival of Reason in a small town, a police observer who personally endorsed the policy nevertheless made an astute observation about the limits of popular support for it. In public, “the people takes giant steps toward the abolition of prejudices and religious superstitions,” he commented, but in their private lives, “not having anything to substitute for the cult they have just overturned, if some accident, some misfortune befalls them, they think it is a punishment from heaven.” In one parish, five newborns had died in two décades. “That was enough to trouble minds, terrify mothers, and make them blame this coincidence on the absence of baptisms.” Another official noted that the closing of the churches angered both older women, who often “took advantage of the long journey [to services] to exchange old stories with other old gossips,” and younger women, who had looked forward to Sunday dances. These comments help explain why women often remained more committed than men to their faith.43

The de-Christianization movement had critics even among supporters of the Revolution. In the south, where the Spanish invaders were posing as defenders of the Church, local authorities warned the Convention that “if the people… hear the apostles of the Revolution trying to persuade them that all religion is based on fable, or on inept absurdities… they will be led to rebel against a new system which seems to be forcing them to renounce their religion and their religious beliefs.” In the Convention, Robespierre opposed the movement, saying that “we must be careful not to give hypocritical counter-revolutionists, who seek to light the flame of civil war, any pretext that seems to justify their calumnies.” He urged the deputies on mission not to give the impression that “war is made on religion itself.”44 The disagreement between the radical de-Christianizers and the majority of the Committee of Public Safety hinted at a growing tension between populists like Hébert and Chaumette, on the one hand, and the Montagnard leaders in the Convention, who were determined to keep extremism under control, on the other.

Despite the tensions over the de-Christianization campaign, the revolutionaries remained united about the necessity of crushing domestic revolts that threatened the Revolution. On October 9, Lyon surrendered, ending the most serious of the federalist uprisings. On October 17, the republican armies, after suffering a string of humiliating defeats in the Vendée throughout the summer, finally won a major victory at Cholet. Rather than retreating south toward the areas where most of their fighters came from, the main rebel force, accompanied by thousands of women and children, unexpectedly crossed the Loire River and began a desperate march to the north; they hoped to reach a point on the coast where they could receive support from the British. The sixty thousand participants in this march heavily outnumbered the scattered republican units in the region; they were not stopped until their attempt to capture the Norman port of Granville, close to the famous abbey of Mont-Saint-Michel, was beaten back on November 14. With the threat of foreign intervention in western France ended, the republicans could turn their efforts to punishing the participants in the uprising.

Punishment of the enemies of the Revolution was one of the most strident demands of the radicals in Paris. They had wanted the revolutionary army units to incorporate revolutionary tribunals and to be equipped with mobile guillotines, so that convicted suspects could be executed immediately. The Convention’s committees feared letting the process of repression get out of hand and resisted these demands; they did, however, approve a series of high-profile political trials in Paris that captured public attention throughout the fall of 1793. The first prominent victim was Marie-Antoinette, whom many revolutionaries now called simply “the widow Capet.” After Louis XVI’s execution in January, she remained in the Temple prison. In the indictment presented by the Revolutionary Tribunal’s prosecutor, Antoine-Quentin Fouquier-Tinville, on October 14, 1793, the misogynist hatred that had followed the queen from the time of her marriage was given full rein. She was accused of having been, “throughout her stay in France, the curse and the parasite of the French,” of having held “conspiratorial meetings… under cover of night” at which all the calamities of the Revolution had been plotted, and of having taught Louis the “dangerous art of dissimulation.” From her exile in London, Madame de Staël insisted that the queen’s fate concerned all French women: “Your empire is doomed if ferocity prevails, your fate is sealed if your tears flow in vain.” Hébert’s assertion that Marie-Antoinette had taught her son to masturbate and had often shared her bed with him justified de Staël’s fear that attacks on the queen would strengthen prejudices against her sex. Marie-Antoinette won a moment of sympathy when she appealed to the women in the audience, saying that “nature refuses to reply to such a charge made against a mother.”45