I could not have written this book alone. Nor did I.

First and foremost, I want to thank Captain Robert Bartlett and the people of the Karluk for letting me tell their story. And I am grateful to William McKinlay for leaving me such a priceless legacy and for sharing his obsession in the materials he left behind.

There are three people without whom I could not have written this book. The journey would have been much less fulfilling had they not shared it with me. I thank my mother and fellow writer, Penelope Niven, for unconditional love, friendship, and endless support and for teaching me from childhood that anything is possible. I thank my father, Jack F. McJunkin, Jr., an artist himself, for bestowing on me a passion for truth, beauty, and all things adventurous. I thank John Hreno, III, for making the fairy tale come true every day, for being there for me in every way, and for giving me the greatest happiness.

I am lucky to have an incredible, amazing literary agent, John Ware, without whom none of this would have happened. Enormous thanks to him, as well as to my fabulous film agent, Martin Shapiro, and the splendid Carole Blake.

Tremendous gratitude goes to my superb editor Will Schwalbe, who has been absolutely wonderful to work with and who has helped make this experience such a positive one. Thanks also to Mark Chait, his top-notch assistant, and the wonderful team at Hyperion for their terrific work—Bob Miller, Martha Levin, Ellen Archer, Michael Burkin, Jane Comins, Phil Rose, April Fleming, and Breene Wesson. With them, The Ice Master has found a marvelous home.

The Ice Master also found a marvelous home at Macmillan of London. Thanks to my sensational editor there, Georgina Morley, who has been such a delightful force, and her sterling assistant Stef Bierwerth. And to the entire outstanding Macmillan group—Ian Chapman, Jeremy Trevathan, Katie James, Caroline Turner, and Lisa Cropman—for everything.

I was fortunate to find the last remaining survivor of the Karluk—Mugpi. I owe her a special tribute for all she endured in 1913–1914, and all she has contributed here. I also thank her daughter, Emily Wilson, for her patience and time, as well as the other descendants of the Karluk’s men, who have become a sort of family to me over the past two years—a family I am honored to be a part of. McKinlay’s daughter, Nancy Scott, has been extraordinary, and endlessly generous in sharing the world of her father with me. She freely opened her home and McKinlay’s life to me. And I want, too, to thank her “other Jennifer,” McKinlay’s granddaughter Jennifer Byrd, for sharing her own insights.

It was the wish of Bjarne Mamen’s mother that his diary and personal papers never be published in full. Yet Jens Anker and Sonja Carling, both relatives of Bjarne Mamen, have been kind enough to share with me what they could, while still respecting the wishes that were expressed long ago. Sandy Anderson’s great-nephew, Peter Anderson, has likewise been generous and forthcoming with his uncle’s materials. And Stuart Jenness, son of Southern Party anthropologist Diamond Jenness, has been a kindred soul and supporter from the beginning of this project. He has been a great resource and has offered indispensable information.

As I embarked on my research for the book, I was warned that the work would not always go smoothly. However, I never experienced anything but the utmost support and assistance from the following institutions and their skilled personnel: The British Columbia Archives (with special thanks to Michael Carter and Kelly Nolin); the Maritime Museum of British Columbia (special thanks to Lynn Wright); the National Archives of Canada (where Marcel Barriault, Marc Bisaillon, Hector Sanscartier, Michel Poitras, Jean Matheson, Larry McNally, Jim F. Kidd, Sere St-Denis, and David Samson were particularly helpful); the National Library of Scotland (thank you Colm McLaughlin, Karen Moran, Irene Danks, and Sally Harrower); Bowdoin College in Maine (with appreciation to Richard Lindemann, Jennifer C. Fradenburgh, Kathryn B. Donahue, Susan Burroughs, and Sean Monahan); Dartmouth College Library (Philip N. Cronenwett); and the Explorer’s Club (Janet E. Baldwin).

In addition, I want to thank the following close, personal friends of William McKinlay for their kindness—Magnus and Mamie Magnusson and Lord George Emslie.

I am blessed with wonderful friends and family who have been nothing but supportive during this time in my life. My soul sister, Melissa McKay, deserves numerous mentions for her constant encouragement, laughter, joy, and commiseration. My oldest friend in the world, Joe Kraemer, deserves many thanks as well for knowing me backward and forward, and for keeping me eternally young. I also give thanks to my beloved grandmother Eleanor Niven and my remarkable aunts and uncles, Lynn Duval Clark, Phil Clark, Doris Knapp, Bill Niven, and Paula and Reid Sturdivant. My cousins have always been more like siblings to me, and they are Lisa Von Sprecken, Derek and Lisa Duval, Shannon Meade, Erik Sturdivant, Evan Sturdivant, and, my other “sister,” Ashley Hurley. Thanks to Patsy and Charles McGee, Frankie and Harry Gamble, and Jimmy and Polly McJunkin. Special thanks to Gayle Keller McJunkin and my little brother, John Keller. And, of course, to my loyal literary cats, Percy Shelley (who never left my side while I was writing) and George Gordon, Lord Byron (who provided much-needed comic relief).

My west coast mother, Judy Kessler, and my dear friend and partner in crime, Angelo Sourmelis, have become my second family. Scott Berenzweig has kept me laughing and has always been there for me when I needed him. And thanks to the “Brother of my Soul” (who wishes to remain anonymous) for Lord Byron and literary discussions. There are friends too numerous to name, but I must mention David Solomon, George Liggins, Phil Fitzgerald, Annie Ward, Carol Edwards, Kyri Smith, Brian Loeser, Lisa Brucker, Bobbie Jo Dombey, Amy Bordy, Jill Lessard, Lori Watanabe, Robert Hamilton, Curtis Atkisson, III, Michael Hawes, Deak and Beth Reynolds, Mike and Melanie Kraemer, Jane and George Silver, Norman Corwin, Barbara Hogenson and Jeffrey Couchman, Loffie and Rob Tyson, Betsy Sulavik Gallagher, Michael Brunet, Mary Ellen Kay, Mike Bertram, and James Earl Jones.

There are others who should be thanked. I benefited greatly from James Ronald Archer’s diligence and persistence. Dr. James Meade was my medical consultant on hypothermia, nephritis, and every other polar malady known to man. Craig R. Harvey, chief coroner of LA County, shared with me his professional opinion on the details of George Breddy’s death. Thanks to Dr. Roger K. Wilkinson for sharing his knowledge of Alister Forbes Mackay; to Adam Hyman and MPH Entertainment for offering their material; and to Richard Diubaldo, an expert on Vilhjalmur Stefansson and the Canadian Arctic. I am also grateful to my favorite photographer, Lisa Keating, and to Peter Martin, Harold A. Pretty, Greg Schenz, Bob Higashi, Brad Wagner, Sharon Obermann, Dan and Dorothea Petrie, the Renfrewshire Taxi Company in Scotland, the American Film Institute and Velva Jean, and Joe Kaiser, for teaching me “pure economy of words.”

I also send special thanks to my high school guidance counselor who told me I should take secretarial classes, just in case my writing career didn’t work out—and who, in saying so, helped inspire me to make it happen.

And on that note, to those who have inspired me—my mother, first of all, along with Anne Brontë, George Sand, and Jane Austen.

Steve Goddard deserves a paragraph of his own for leading me to the remains of Sandy Anderson’s party. It was his fortuitous e-mail that alerted me to the auction on eBay. And thanks, too, to Jerry and Vangie Lee, for selling me the artifacts and for posting them on eBay in the first place.

I want to pay tribute to McKinlay’s granddaughter, Tricia Scott, who is no longer here. And to the late Lucy Kroll, who believed in me years ago, before I was old enough to understand.

Finally, there are several important people in my life whom I will always miss, and with whom I wish I could share this experience now: Jack and Cleo McJunkin, who made me feel like the center of their world; Olin Niven, for knowing instinctively when he was needed and for teaching me the true meaning of the word “gentleman”; and Dick Knapp, who should have lived to see this book, and many more.

Captain Robert Bartlett, the ice master whose leadership and courage rallied the crew of the Karluk when disaster struck.

The scientific staff of the Canadian Arctic Expedition of 1913, taken in Nome shortly before the Karluk sailed. Front row, left to right: Dr. Alister Forbes Mackay, Captain Robert Bartlett, Vilhjalmur Stefansson, Dr. Rudolph Martin Anderson, James Murray, Fritz Johansen. Back row, left to right: Bjarne Mamen, Burt McConnell, Kenneth Chipman, George Wilkins, George Malloch, Henri Beuchat, J.J. O’Neill, Diamond Jenness, John Raffles Cox, William McKinlay.

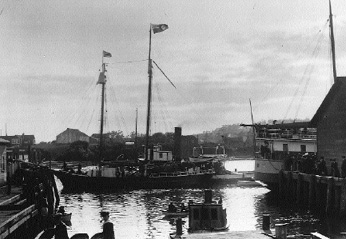

HMCS Karluk in Victoria Harbour in June 1913. The ill-equipped, run-down ship attracted huge crowds to speed her departure.

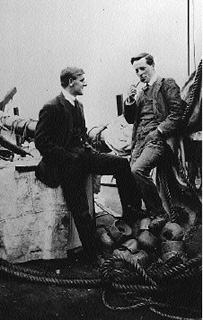

Diamond Jenness and William McKinlay aboard the Karluk in June 1913. Jenness, an anthropologist, and McKinlay, a magnetician, were known as the twins because of their short stature.

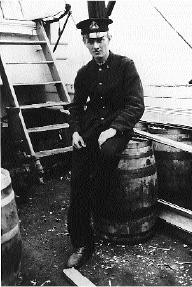

George Malloch, geologist, on board the Karluk in June 1913. His comical, easy-going nature provided welcome comfort to his shipmates.

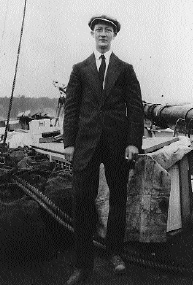

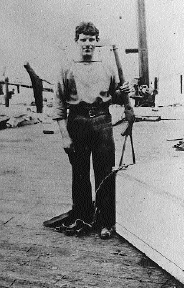

Alexander “Sandy” Anderson, promoted to first mate when his predecessor was dismissed before the expedition set sail. His youth and relative inexperience were fully compensated for by his enthusiasm and dedication to duty.

Bjarne Mamen, at twenty-two the youngest member of the scientific staff, begged to join the expedition and was accepted despite his lack of experience.

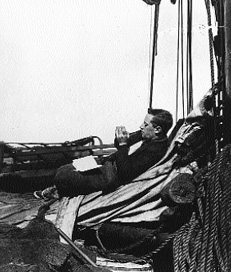

William McKinlay relaxing on the deck of the Karluk. A Scottish schoolmaster, McKinlay had long dreamed of being an explorer but until now his only experience of the Arctic was from the books he had read.

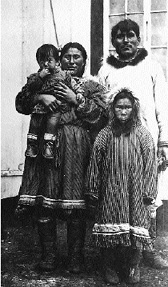

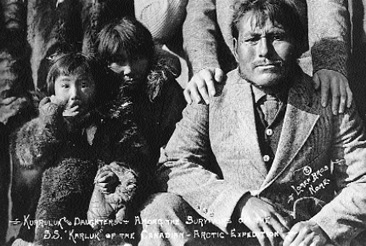

Kuraluk and Kiruk (who became known as “Auntie”) with their two children, Helen, then aged eight and Mugpi, aged three. They were hired to hunt and to sew winter clothes for the members of the expedition.

Chief Engineer John Munro who, though lazy and ineffectual, was left in command on Wrangel Island by Captain Bartlett.

George Breddy, the Karluk’s stoker, and one of the more volatile crew members. His instability and deviousness would lead to one of the most traumatic incidents of the entire expedition.

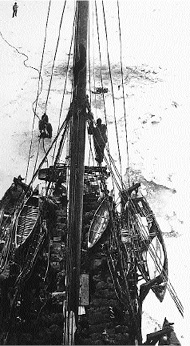

The Karluk forcing a path through the ice pack in August 1913, as an early winter set in.

With the Karluk trapped in the ice, the scientists and crew began to unload supplies onto the ice pack.

Vilhjalmur Stefansson, a renowned explorer who believed that anyone could survive in the place he called the “friendly Arctic.”

“Goodbye, Stefansson. We did not then know that those of us who were left on your luckless ship were not to see you again.” From the notes of Fred Maurer, September 1913.

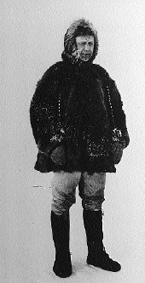

Bjarne Mamen in the regulation polar explorer’s kit. The clothes on board were thin hand-me-downs, purchased cheaply, and not issued to everyone.

The last photograph of the Karluk before she went down. The ice blocks surrounding the hull were cut from the ice pack in an effort to insulate the ship from the bitter cold of the Arctic winter.

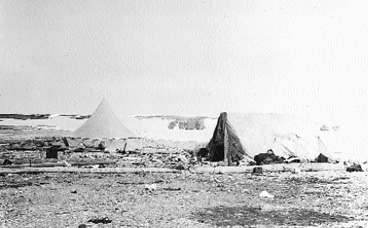

Shipwreck Camp.

“To look at the ice, one would think it impossible ever to get through it. In some parts there are ridges of 60 or 70 ft. in height, some even higher, with a sheer vertical face on one side as smooth as if they had been built by human hands. And we must get over & through & we must camp here until we have made that passable.” William McKinlay, March 1914.

“Wrangel Island is eighty-five miles long, and varies from twenty-eight to thirty-five miles in width, and is practically all mountainous. It lies one hundred miles off the coast of Siberia and is the most desolate-looking place I have ever seen, or ever wish to see again.” Ernest Chafe, March 1914.

Kataktovik on Wrangel Island shortly before he and Captain Bartlett set out on their extraordinary 700-mile journey across the ice to Siberia to get help. Apart from Helen and Mugpi, Kataktovik was, at nineteen, the youngest member of the expedition.

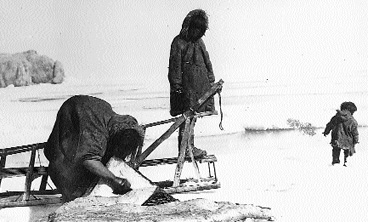

Auntie with Helen and Mugpi on Wrangel Island, skinning a seal. The Eskimos were the hunters and were responsible for finding at least 80 percent of the game on the island.

Nigeraurak, the ship’s cat and good luck mascot. Little Mugpi used to tease the kitten and was rewarded with a deep scratch, which left a distinct scar.

Mugpi, now four years old, with one of the ship’s dogs.

From left to right, Ernest Chafe, John Hadley, Robert Williamson, Kuraluk, Mugpi, and Helen butchering a walrus. Chafe is holding the animal’s flippers.

The meat rack. After butchering game, the meat would be left to dry in the sun to preserve it for winter supplies.

John Hadley, a trapper who had joined the Karluk to escape his grief following the death of his Eskimo wife. He is shown here with his faithful dog, Molly.

William McKinlay, Robert Williamson, George Breddy, Ernest Chafe, and “Clam” Williams. A rare photograph of scientists and crew together. The divisions between them, already noticeable onboard ship, became even more marked on the island. The camp would ultimately split in two, with McKinlay joining the Eskimos’ tent.

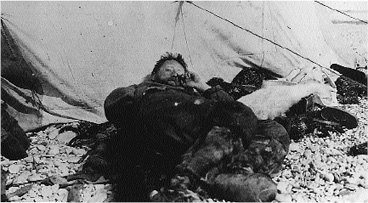

William McKinlay, exhausted and suffering from snow blindness, lying outside his tent at Cape Waring.

The camp at Cape Waring. The divisions in the camp are all too clearly visible, with the crewmen’s tent on the left and the Eskimos’ tent—shared with McKinlay and Hadley—on the right.

“Clam” Williams with one of the ship’s dogs on Wrangel Island. The only member of the crew on the island to behave honorably.

John Munro and Robert Templeman, the Karluk’s cook, at Rodger’s Harbour, 60 to 70 miles south east of Cape Waring. They had established a camp there to await the rescue ship for which the Karluk’s survivors were so desperately hoping.

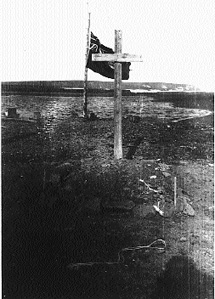

The Canadian flag flying at half mast over the grave of George Malloch and Bjarne Mamen at Rodger’s Harbour.

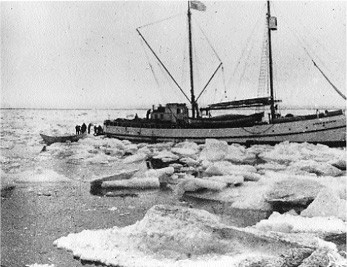

The longed-for ship, the King and Winge, which forged through the ice to reach the survivors on Wrangel Island in September 1914.

Mugpi, Helen, and Kuraluk on their way back to Alaska.

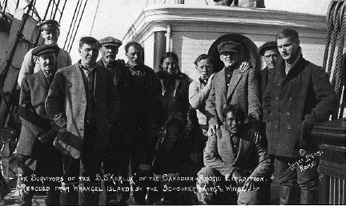

The survivors of the Canadian Arctic Expedition, from left to right: John Munro (at the back), Robert Templeman, Robert Williamson, John Hadley, Captain Robert Bartlett, Auntie, Mugpi, Helen, William McKinlay, Kuraluk (seated in front), Ernest Chafe, “Clam” Williams, and Fred Maurer.

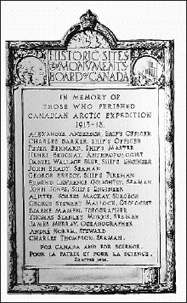

The plaque commemorating those who died. In a curious twist of fate, this plaque is itself now missing, having been lost when the National Archives of Canada moved buildings in the 1960s.