Jacques Derrida was a philosopher. Yet he never wrote anything straightforwardly philosophical.

His work has been heralded as the most significant in contemporary thinking. But it’s also been denounced as a corruption of all intellectual values.

Derrida has famously been associated with something called DECONSTRUCTION. Yet of all development in contemporary philosophy, deconstruction might be the most difficult to summarize…

There have been many answers.

All of these (and more) have been said of deconstruction. But there’s some consensus on one point: its leading exponent has been Jacques Derrida.

Derrida’s writing undermines our usual ideas about texts, meanings, concepts and identities – not just in philosophy, but in other fields as well.

Reactions to this have ranged from reasoned criticism to sheer abuse – deconstruction has been controversial. Should it be reviled as a politically pernicious nihilism, celebrated as a philosophy of radical choice and difference… or what?

There’s much more to Derrida’s work than the public controversies suggest. But controversy can reveal something about what’s at stake in contemporary philosophy. A small quarrel at Cambridge has done precisely that…

According to a tradition dating from 1479, English universities award honorary degrees to distinguished people. It’s never been quite clear why. But it’s assumed that both parties benefit.

On 21 March 1992, senior members of the University of Cambridge gathered to decide its annual awards. It should have been a formality – no candidate had been opposed for twenty-nine years. But the name Jacques Derrida was on the list. Four of the dons ritually declared non placet (“not contented”). They were Dr Henry Erskine-Hill, Reader in Literary History; Ian Jack, Professor of English Literature; David Hugh Mellor, Professor of Philosophy; Raymond Ian Page, Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon. And they forced the University to arrange a ballot.

NON PLACET NON PLACET NON PLACET NON PLACET

There were two problems. First, this was a boundary dispute. Most of Derrida’s proposers were members of the English faculty, but by training and profession Derrida was a philosopher. But more trenchantly, Cambridge traditionalists in both disciplines saw Derrida’s thinking as deeply improper, offensive and subversive.

Campaigns were organized, and the Press was alerted. To the outraged dons, Derrida represented an insidious, fashionable strand of “French theory”. They struck Anglo-Saxon attitudes…

FRENCH ACADEMIC PHILOSOPHY RUNS BY A SYSTEM OF MANDARINS AND GURUS AND FASHIONS. THEY WOULD BE GENERALLY PERCEIVED BY BRITISH PHILOSOPHERS AS NOT HAVING THE SAME STANDARDS OF PRECISION AND CLARITY AND RIGOUR WE WOULD. [David-Hillel Ruben] LOTS OF PEOPLE THESE DAYS INVOKE SOMETHING CALLED “THEORY”, WHICH I THINK A PROPER PHILOSOPHER WOULD NOT ADMIT TO. WHAT SORT OF WRITER IS DERRIDA? IS HE A FAILED THEORIST? IF NOT A THEORIST, THEN WHAT IS HE? [Henry Erskine-Hill] THE FRENCH EXCEL IN FABRICATED TERMS OF SHIFTY MEANING WHICH MAKE IT IMPOSSIBLE TO DETECT AT WHAT POINT PHILOSOPHICAL SPECULATION TURNS TO GIBBERISH. DECONSTRUCTION IS A THEORY WHICH APPEARS TO LEND ITSELF MOST READILY TO BABBLING OBFUSCATION [Peter Lennon]

THESE ARE ABSURD DOCTRINES WITH DISMAYING IMPLICATIONS.… THEY DEPRIVE THE MIND OF ITS DEFENCES AGAINST DANGEROUSLY IRRATIONAL IDEOLOGIES AND REGIMES. [Prof. David Mellor and others – anti-Derrida flysheet] TO CALL HIS THINKING NIHILIST WOULD BE TO FLATTER IT BY SAYING IT WAS INTELLIGIBLE [Prof. Barry Smith in The Times.]

19 academics summed up the indictments in a letter to The Times:

Derrida is accused of obfuscation, trickery and charlatanism.

He’s not a philosopher, he’s a flim-flam artist. And strangely, his trivial joking gimmickry is seen as a powerful threat to philosophy – a corrosion in the very foundations of intellectual life.

But Derrida had his defenders, such as Jonathan Rée: “The traditionalists were offering a mere and meagre argument from authority. They were refusing the possibility of dissent from established systems – an establishment stance, yes, but scarcely a philosophical stance…”

The ballot on 16 May vindicated Derrida and his supporters by 336 votes to 204. Derrida collected his award. But the dispute has continued.

What was at stake? Underneath the posturing, there were two important questions:

If the dons had wanted a rigorous address to these questions, they might have found one in the writings of a certain Jacques Derrida…

Derrida’s writing is a radical critique of philosophy. It questions the usual notions of truth and knowledge. It disrupts traditional ideas about procedure and presentation. And it questions the authority of philosophy.

PHILOSOPHY IS FIRST AND FOREMOST WRITING. THEREFORE IT DEPENDS CRUCIALLY ON THE STYLES AND FORMS OF ITS LANGUAGE – FIGURES OF SPEECH, METAPHORS, EVEN LAYOUT ON THE PAGE JUST AS LITERATURE DOES.

So Derrida writes “philosophy” in something like “literary” ways. That’s one reason for the anxieties at Cambridge. Derrida’s critique of philosophy puts boundaries between philosophy and literature into question.

Derrida has destabilized other boundaries. He’s taken his way of doing philosophy into art, architecture, law and politics. He’s engaged with nuclear disarmament, racism, apartheid, feminist politics, the question of national identities, and other issues – including the authority of teaching institutions.

The profile of a joker? Perhaps, if we’re willing to re-think joking …

By the time of the Cambridge dispute, Jacques Derrida’s institutional credentials were internationally acknowledged.

Derrida was born in Algeria in 1930 to a lower middle-class, Sephardic Jewish family.

He studied philosophy in Paris with the Marx and Hegel scholar, Jean Hyppolite, at the École Normale Supérieure (1952-6). His work on phenomenology was quickly recognized: a scholarship to Harvard in 1956, the Prix Cavaillès in 1962.

He taught philosophy at the Sorbonne (1960-4) and the École Normale Supérieure (1964-84). From 1984, he was Director of Studies at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales. These are well-founded institutions.

He taught regularly at Yale and Johns Hopkins universities in the USA. Alarmingly for the Cambridge dons, his ideas were attractive. By the early 1980s, “Yale deconstruction” had introduced a wide Anglophone readership to the name Derrida, now one of the best-known names in international contemporary philosophy. He died in Paris on 8 October 2004.

So Jacques Derrida was an establishment figure? Not entirely …

In 1957 Derrida planned a doctoral thesis on Husserl’s phenomenology. But he abandoned it.

IS IT POSSIBLE TO WRITE ABOUT PHILOSOPHICAL WRITING WITHIN THE LIMITS OF AN ACADEMIC THESIS? WOULDN’T IT HAVE TO PERFORM WHAT IT ARGUED, AND THEREFORE HAVE TO BE WRITTEN DIFFERENTLY? WHAT IF THE EXAMINERS INSIST ON THE STANDARD PHILOSOPHICAL PROTOCOLS – THE ONES I WANT TO QUESTION?

Instead, Derrida embarked on a set of critical encounters with Western philosophy, literature and theory.

In philosophy this included German idealism (Kant and Hegel), phenomenology and its critics (Husserl, Heidegger and Lévinas), and the writings of Plato, Rousseau, Nietzsche and others.

Among literary writers, Mallarmé, Jabès, Artaud, Kafka, Joyce, Blanchot and Ponge figured prominently.

And between 1965 and 1972, Derrida was in contact with the Tel Quel group (Philippe Sollers, Julia Kristeva, Roland Barthes, and others). They debated contemporary theory, especially psychoanalysis, structuralism, and Marxism.

Derrida’s critique of philosophy is not a standard critique. It’s not couched in the usual terms.

Derrida doesn’t adopt any fixed position among competing tendencies and traditions. He doesn’t simply advocate or refute any of them. And he doesn’t advance any overarching theories, concepts, methods or projects of his own.

So Derrida’s writing is impossible to summarize. In his terms it has no “basic” concepts or methods to pick out and explain. Yet it alludes constantly to a wide range of Western thinking. And it’s often strategically convoluted. It disobeys the usual procedures – start at the beginning, lay out the exposition, advance the propositions, make a conclusion, etc.

The Cambridge dons were right. Derrida’s writing is difficult and maybe subversive. It has a rigour and a logic, but of an unfamiliar order.

Is there a way of beginning to read this writing?

If Derrida’s writing has no extractable concepts or method, we can still look at what it does: what effects it has.

Derrida offers a way of thinking these effects. By his own account, his writing has a matrix. Its two strands are DERAILED COMMUNICATION and UNDECIDABILITY. Derrida finds both of these in the figure of the virus.

EVERYTHING I HAVE DONE IS DOMINATED BY THE THOUGHT OF A VIRUS, THE VIRUS BEING MANY THINGS. FOLLOW TWO THREADS. ONE, THE VIRUS INTRODUCES DISORDER INTO COMMUNICATION, EVEN IN THE BIOLOGICAL SPHERE – A DERAILING OF CODING AND DECODING. TWO, A VIRUS IS NOT A MICROBE, IT IS NEITHER LIVING NOR NON-LIVING, NEITHER ALIVE NOR DEAD. FOLLOW THESE THREADS AND YOU HAVE THE MATRIX OF ALL I HAVE DONE SINCE I STARTED WRITING.

We can take the second threat first: UNDECIDABILITY. If the virus is neither living nor non-living, then it’s puzzlingly undecidable. As we’ll see, undecidability is a thread to the traditional foundations of philosophy. But it’s also a thread that can be picked up “outside” philosophy, in the cinema…

The zombie is a late arrival in Western culture. It figures in the religion of enslaved West Africans in Haiti from the 17th century. For two hundred years Western colonialists pictured “voodoo” as a terrorist religion of blood sacrifices and cannibalistic atrocities.

But the zombie is a different kind of terror: a body without soul, mind, volition or speech. It’s said to be a reactivated corpse, or a living body rendered soulless and mindless by sorcery.

The zombie entered Western popular culture in the late 1920s. White Zombie, 1932, set the formula for Hollywood: white science meets black magic.

It’s an anxious encounter. What if the Western rationalist distinction of “life” and “death” doesn’t hold?

The anxiety has taken many forms. Zombies have been cast as catatonic lovers, inner-city policeman, invaders from the stratosphere, military expeditionaries, night club entertainers, and so on.

BUT WHATEVER THE SCENARIO, THE ZOMBIE HAS A BASIC MODEL: ALIVE BUT DEAD, DEAD BUT ALIVE. IN A CULTURE WHICH SEPARATES THE LIVING FROM THE DEAD, THE ZOMBIE OCCUPIES THE SPACE IN BETWEEN.

Between life and death – it’s an uncertain space. The zombie might be EITHER alive OR dead. But it cuts across these categories: it is BOTH alive AND dead. Equally it is NEITHER alive NOR dead, since it cannot take on the “full” senses of these terms. True life must preclude true death. The zombie short-circuits the usual logic of distinction. Having both states, it has neither. It belongs to a different order of things: in terms of life and death, it cannot be decided.

According to Hollywood, the zombie is a “secret we must refuse to believe, even if it’s true”.

UNDECIDABLES ARE THREATENING THEY POISON THE COMFORTING SENSE THAT WE INHABIT A WORLD GOVERNED BY DECIDABLE CATEGORIES.

The terms “life” and “death” from a BINARY OPPOSITION: a pair of contrasted terms, each of which depends on the other for its meaning. There are many such oppositions, and they’re all governed by the distinction. EITHER/OR.

If we accept this, it establishes conceptual order. Binary oppositions classify and organize the objects, events and relations of the world. They make decision possible. And they govern thinking in everyday life, as well as philosophy, theory and the sciences.

Undecidables disrupt this oppositional logic. They slip across both sides of an opposition but don’t properly fit either. They are more than the opposition can allow. And because of that, they question the very principle of “opposition”.

Zombies are cinematic inscriptions of the failure of the “life/death” opposition. They show where classificatory order breaks down: they mark the limits of order.

Like all undecidables, zombies infect the oppositions grouped around them. These ought to establish stable, clear and permanent categories.

But what happens to “white/black”, “master/servant”, and “civilized/primitive”, when white colonialists can also be the zombie slaves of a black power? Can “white science/black magic” remain untroubled, if what sometimes works against a zombie is white magic – the Christian religion, the power of love or superior morality? How certain is the opposition “inside/outside”, if the zombie’s internal soul is extracted and an external force becomes its inside? Is there any security in opposing “masculine” to “feminine” and “good” to “evil”, when the zombie is usually de-sexualized and has no power of decision?

The Zombie is therefore fascinating and also horrific. It poisons systems of orders, and like all undecidables ought to be returned to order.

In zombie movies, this return to order is difficult. For a classic satisfying ending, the troubling element has to be removed, perhaps by killing it. But zombies are already dead (while alive). You can’t kill a zombie, you have to resolve it. It has to be “killed” categorically, by removing its undecidability. A magic agent or superior power will have to decide the zombie, returning it to one side of the opposition or the other. It has to become a proper corpse or a true living being.

At that point the familiar concepts of life and death can rule again, untroubled. This is a restoration of conceptual order.

There are other endings, less final. The zombies might be ineradicable, they might return. Perhaps undecidability is always with us. If not figured in the zombie, then something else: ghosts, golems or vampires, between life and death. Between male and female, the androgyne. Between human and machine, the android. Between friends and enemies, the stranger…

WHAT IF THE COMFORT OF ORDER IS NOT TO BE RESTORED? … … WHAT IF WE INSIST ON UNDECIDABILITY … … THE CEASELESS PLAY OF EITHER/OR … … NEITHER/NOR… … BOTH?

Derrida argues that undecidability is a component of Western philosophy, but one which philosophy must refuse to recognize – or it will no longer be “philosophy” as we’ve known it. (It’s a “truth we must refuse to believe”…)

Derrida detects the play of undecidability even in the foundational texts of the Western tradition, such as those of Plato (428-347 BC). Pupil of Socrates and founder of the Athenian Academy, writer on ethics, politics, law and metaphysics, Plato is an inaugural figure of Western philosophy, and widely influential on later thinking.

FOR ME, SOCRATIC REASONING IS THE ONLY TRUE ROUTE TO KNOWLEDGE.

Plato sets the love of reason and truth against all purveyors of false wisdom:-the sophists and rhetoricians, whose persuasive word-play deludes the untrained; and the poets, mythologists and story-tellers who merely imitate nature or “repeat-without-knowing”. True philosophy is the active employment of reason.

How, then, does Derrida read Plato?

In “Plato’s Pharmacy” (1969) Derrida focusses on the Phaedrus, a fictionalized conversation between two historical characters: Socrates and Phaedrus, a young Athenian swayed by the rhetoricians. The topic: the relative merits of the lover and the non-lover, as sexual partners and as thinkers. Or perhaps the topic is the relative merits of rhetoric and philosophy (or perhaps, the merits of speech and writing).

MY CONCERN IS SPEECH AND WRITING. I EXAMINE THE SHORT FINAL SECTION IN WHICH SOCRATES (WHO NEVER WROTE ANYTHING) CONVINCES PHAEDRUS THAT SPEECH IS SUPERIOR TO WRITING…

IS WRITING SEEMLY? DOES THE WRITER CUT A RESPECTABLE FIGURE? IS IT PROPER TO WRITE? OF COURSE NOT BUT SOCRATES IS NOT GOING TO USE RATIONAL ARGUMENT MYTH WILL STRIKE THE FIRST BLOW …

AS FAR AS WORDS ARE CONCERNED, DO YOU KNOW WHAT WOULD MOST PLEASE THE GODS? NO, I DON’T. DO YOU?

WELL, I CAN TELL YOU WHAT I’VE HEARD FROM OUR PREDECESSORS …

… THEY SAY THAT THERE DWELT AT NAUCRATIS IN EGYPT ONE OF THE ANCIENT GODS OF THAT COUNTRY, AN INVENTOR-GOD WHOSE NAME WAS THEUTH.

HE INVENTED NUMBERS AND CALCULATION AND GEOMETRY AND ASTRONOMY, AS WELL AS GAMES OF DRAUGHTS AND DICE, AND ABOVE ALL …

… WRITING.

AT THAT TIME THE GREAT GOD-KING OF ALL OF UPPER EGYPT WAS THAMUS. THE GREEKS CALL HIM AMMON. THEUTH CAME TO HIM AND EXHIBITED HIS INVENTIONS, SAYING THAT THEY OUGHT TO BE MADE KNOWN TO ALL THE EGYPTIANS. … HIS INVENTIONS WILL HAVE NO VALUE UNLESS GOD-THE-KING APPROVES OF THEM.

THAMUS INQUIRED INTO EACH ONE OF THEM, CONDEMNING SOME AND PRAISING OTHERS. IT WOULD TAKE TOO LONG TO GO THROUGH ALL OF THEM. BUT WHEN IT CAME TO WRITING. … THIS BRANCH OF LEARNING, MY LORD, WILL MAKE THE EGYPTIANS WISER AND IMPROVE THEIR MEMORIES, FOR I’VE DISCOVERED A PHARMAKON FOR MEMORY AND WISDOM.

Pharmakon is a Greek word which could be translated as “magic potion”. Other English translations have used “recipe”, “receipt”, “specific”, “cure” and “remedy”. But as Derrida notes, pharmakon is a specially ambiguous word.

In Greek, pharmakon means both cure and poison. Like the English word “drug”, it has good and bad aspects. Some translations resolve the word, cutting out one of its poles. But the pharmakon is UNDECIDABLE, inhabiting both the curative and the poisonous.

THEUTH HAS OFFERED WRITING AS A PHARMAKON. DOES HE MEAN “CURE”? SURELY HE WANTS TO WIN HIS CASE. WRITING IS A REMEDY FOR DEFICIENT MEMORY AND LIMITED WISDOM. THE KING’S REPLY WILL BE INCISIVE …

THE DISCOVERER OF AN ART IS NOT THE BEST PERSON TO JUDGE ITS HARM OR BENEFIT. YOU, THE FATHER OF WRITING, ARE SO FOND OF YOUR OFFSPRING THAT YOU’VE STATED EXACTLY THE OPPOSITE OF WHAT IT WILL DO …

THOSE WHO WRITE WILL STOP EXERCISING THEIR MEMORY AND BECOME FORGETFUL. THEY’LL RELY ON THE EXTERNAL MARKS OF WRITING INSTEAD OF THEIR INTERNAL CAPACITY TO REMEMBER THINGS. YOU’VE DISCOVERED A PHARMAKON FOR REMINDING, NOT FOR TRUE MEMORY…

AS FOR WISDOM, YOU OFFER YOUR STUDENTS A MERE APPEARANCE OF IT, NOT THE REALITY. THEY’LL RECEIVE MANY THINGS FROM YOU, BUT WITHOUT PROPER INSTRUCTION. THEY’LL SEEM KNOWLEDGEABLE WHEN THEY’RE QUITE IGNORANT. AND THEY’LL BE HARD TO GET ALONG WITH – THEY’LL CARRY THE CONCEIT OF WISDOM, INSTEAD OF BEING REALLY WISE.

WHAT YOUR THEBAN SAYS IS QUITE SOUND. I’M SURE. LIKE PORTRAIT PAINTINGS, WRITING IS LIFELESS. IT CAN’T ANSWER BACK WHEN YOU ASK IT A QUESTION. AND WRITING CAN BE BANDIED AROUND ANYWHERE, AMONG THOSE WHO UNDERSTAND AND THOSE WHO HAVE NO BUSINESS WITH IT.

IT CANNOT KNOW WHO IT OUGHT TO SPEAK TO. WHEN IT’S UNFAIRLY ABUSED, IT NEEDS ITS FATHER THERE TO SUPPORT IT, BECAUSE IT’S QUITE INCAPABLE OF HELPING OR DEFENDING ITSELF.

WRITING IS CONDEMNED: REAL MEMORY WILL DECLINE, TRUE EDUCATION WILL BE CORRUPTED, FALSE KNOWLEDGE WILL REPLACE TRUE WISDOM. WRITING IS LIFELESS, ORPHANED AND HELPLESS.

But Theuth offered it as a pharmakon. Thamus, with all the authority of the king of kings and god of gods, returns it decided. Writing is a poison!

Writing as an undecidable has been returned “decided”. Derrida wants to keep it in play.

He shows how Plato’s argument depends throughout on a set of simple, clear-cut oppositions:

good/evil, inside/outside, true/false, essence/appearance, life/death.

Plato’s definition of writing is inserted into these oppositions. Speech is good, writing bad. True memory is internal, written reminding is external. Speech carries the essence of knowledge, writing its appearance. Spoken signs are living, written marks lifeless.

IF ONE GOT TO THINKING THAT SOMETHING LIKE THE PHARMAKON GOVERNED THESE OPPOSITIONS, ONE WOULD HAVE TO BEND INTO STRANGE CONTORTIONS WHAT COULD NO LONGER SIMPLY BE CALLED “LOGIC”.

In Derrida’s view, writing has characteristics that can’t be decided within these oppositions. It disrupts the oppositions. It plays across good and bad, curative and injurious. There is neither simply cure nor simply poison. The characteristics of writing inhabit “interior” memory while also being “external”. “Living” speech shares in the characteristics of “dead” writing. Writing refuses to settle down as the mere “appearance” of “true” knowledge.

Even Plato cannot avoid this. He resorts to metaphors of writing to describe “true” knowledge and “internal” memory.

THE ONLY SPEECHES THAT ARE WORTHY OF SERIOUS ATTENTION ARE THOSE THAT ARE TAUGHT AND SPOKEN FOR THE SAKE OF LEARNING, AND ACTUALLY WRITTEN IN THE SOUL. WRITING AS PHARMAKON CANNOT BE FIXED DOWN WITHIN PLATO’S OPPOSITIONS. THE PHARMAKON HAS NO PROPER OR DETERMINATE CHARACTER. IT IS THE PLAY OF POSSIBILITIES, THE MOVEMENTS BACK AND FORTH, INTO AND OUT OF THE OPPOSITES.

Once the aberrant logic of the pharmakon is let loose, it poisons the fixity and clarity of the other oppositions grouped around it. For instance, Plato’s argument relies on father/son, Egyptian/Greek, original/derivation. Can we be sure of these?

In Derrida’s hands, they start to unravel. He turns to the “original” Egyptian myth where the characters are Thoth and King Ammon. Thoth is the son of the sun god, Ammon.

Derrida introduces the SUPPLEMENT. Thoth is the supplement to Ammon. The French word supplément means both addition and replacement. The supplement both extends and replaces – as a dietary supplement both adds to the diet and becomes part of the diet.

The supplement obeys a strange logic.

To be an addition means to be added to something already complete …

…yet it cannot be complete if it needs an addition. The king is complete and has an addition; needing an addition, the king is not yet whole.

The supplement extends by repeating. The king’s son has the same blood and is the king’s extension. But the supplement opposes by replacing. The king’s son will usurp the king, take his place.

The declaration, “The king is dead, long live the king!” must escape the grip of standard logic. It follows the logic of the supplement. The king must be the same but different: he is figured twice, as the father-king and the supplement-king.

So Thoth opposes his father-king, but he opposes what he himself repeats. He opposes himself. Thoth, the demi-god, is undecidable. And so is Theuth, his Greek counterpart…

“Theuth is thus the father’s other, the father, and himself. He cannot be assigned a fixed location in this play. Sly, slippery and masked, an intriguer and a card, he is neither king nor jack, but rather a sort of joker, a floating signifier, a wild card, one who puts play into play.” And this joker is the inventor of play, of games of draughts, dice, etc.

Every act of his is marked by an unstable ambivalence. He is the god of calculation, arithmetic and rational science; and he also presides over the occult sciences, astrology and alchemy. He is the god of magic formulae, of secret accounts, of hidden texts. And so he is the god of medicine. The god of writing is the god of the pharmakon…

So can Theuth simply have meant writing as a “remedy”? Isn’t the undecidable demi-god condemned to invent undecidables? Not just remedies, but pharmakons? And Derrida asks, “Isn’t Theuth’s desire for writing a desire for orphanhood and patricidal subversion? Isn’t this pharmakon a criminal thing, a poisoned gift?”

Plato’s attempts to fix down fathers/sons and original/derivative are also attempts to fix down “philosophy”. But philosophy has no easy remedy for undecidables. Derrida takes up some related words.

PHARMAKEUS, magician or sorcerer, is applied to Socrates himself by his accusers and enemies. Is Socrates working by enchantment? Is the sorcery of the undecidable inside philosophy, inescapably part of philosophical method?

PHARMAKOS means scapegoat. It’s an evil found inside the city that must be cast out to maintain the city’s purity. The scapegoat must belong to the inside, but must also belong to the outside. It’s an undecidable. Writing is the undecidable pharmakos of philosophy. Found inside philosophy (Plato writes), it needs to be cast out (Plato condemns writing). Philosophy is set against itself.

“Inside/outside” assures us of order. On its assurance, Plato tells us what is properly “inside” philosophy. Derrida’s strategies unfix the order.

This is not standard philosophical procedure. We’d expect a refutation of Plato or a confirmation: a clear agreement or disagreement. Or we’d expect the offer of “true” or “correct” meanings, or some explanation of Plato’s “major concepts”.

Such readings would reproduce Plato’s logic: the attempt to master undecidability.

Instead of countering Plato’s argument, or approving it or modifying it, Derrida insists on its instabilities. It is inhabited at every turn by an undecidability that it cannot fully master.

TO COME TO AN UNDERSTANDING WITH PLATO, IN THE WAY I’VE SKETCHED OUT, IS ALREADY TO SLIP AWAY FROM THE RECOGNIZED MODELS OF COMMENTARY, WHETHER THEY TRY TO CORROBORATE OR REFUTE, TO CONFIRM, OR TO OVERTURN, OR TO MARK A RETURN-TO-PLATO.

ISN’T THIS PLAY WITH WORDS, WITH THEIR LOCATIONS AND MEANINGS, MORE LIKE LITERARY CRITICISM OR COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY OR SOMETHING ELSE?

Derrida does not so much explain Plato’s text as “unfix” it. He sets its undecidables into unlikely movement.

Now from the perspectives of Plato’s usual commentators, his operations seem open to the charges of the Cambridge professors: philosophically insignificant, lacking in rigour, contaminating, and so forth…

DERRIDA’S TEXT CANNOT BE EITHER IMPORTANT OR EVEN PROPERLY PHILOSOPHICAL. DERRIDA IS TURNING ASIDE A SERIOUS PHILOSOPHICAL QUEST, DELIBERATELY PERVERTING IT. IT’S JUST A LITERARY-POETIC PLAY ON TURNS OF LANGUAGE.

Can Derrida’s strategies be “important” to philosophy? Everything is against it. It’s destined to miss the point, to pull Plato’s text outside of philosophy, to trivialize Plato’s thought.

But Derrida is confronting an argument for the priority of speech over writing. A side issue? According to Derrida, setting speech to rule over writing is crucial to the underpinning presuppositions of Western philosophy.

IF SO, TO UNDERMINE THE PRIVILEGE OF SPEECH IS ALSO TO UNDERMINE THE FOUNDATIONS OF WESTERN PHILOSOPHY.

This is a large claim. First, is it plausible? Have philosophers privileged speech?

Derrida maintains that through three millenia of Western philosophy, from Plato and Aristotle to Rousseau, Hegel, Husserl and others, philosophers have indeed privileged speech.

What have they claimed?

THE VOICE IS THE PRIVILEGED MEDIUM OF MEANING.

This is phonocentrism: the voice is the centre

Writing is derivative …

If the voice is king, writing is its enemy. Writing is a pernicious threat to the true carrier of meaning.

If writing represents speech, speech is the representative of THOUGHT, of sovereign idea, of ideation, of consciousness itself.

In the chain thought………speech………………writing, speech lies closest to thought.

SPOKEN WORDS ARE THE SYMBOLS OF MENTAL EXPERIENCE. AND WRITTEN WORDS ARE THE SYMBOLS OF SPOKEN WORDS. LANGUAGES ARE MADE TO BE SPOKEN. WRITING SERVES ONLY AS A SUPPLEMENT TO SPEECH. THE SPOKEN WORD ALONE IS THE OBJECT OF LINGUISTIC STUDY. WRITING IS A TRAP ITS ACTIONS ARE VICIOUS AND TYRANNICAL. ALL ITS CASES ARE MONSTROUS. LINGUISTICS SHOULD PUT THEM UNDER OBSERVATION IN SPECIAL COMPARTMENTS.

This doesn’t square easily with the social history of the rise of writing in the West. Can we imagine capitalist economics, the power of the Christian Church, political systems, military structures, law, education, the arts, without records, books, writing? Literacy is the cornerstone of class education, safeguarded as the written and the readable, not the speakable and the audible.

Doesn’t the history of the West in fact privilege writing?

The philosophers must be wrong. Have they fallen into avoidable error?

There are some arguments on their side. Sometimes speech is offered a curious privilege …

I PROMISE TO TELL THE TRUTH, THE WHOLE TRUTH, AND NOTHING BUT THE TRUTH

THE ARGUMENT OF MY THESIS IS …

I CALL UPON THE SECRETARY TO READ THE MINUTES OF THE LAST MEETING

I DECLARE THIS SHOPPING MALL “OPEN”.

But that’s not quite Derrida’s argument. First, paradoxically, phonocentrism is a “history of silence”, a repression of writing which can scarcely be acknowledged.

Secondly, the suppression of writing is necessary to Western philosophy, and all thinking influenced by it. It is crucial to philosophy’s metaphysical presuppositions…

Metaphysics inquires into aspects of reality which seem to lie beyond the empirically knowable world, out of reach of scientific methods. Its questions look like the philosophical questions: essential truth, being and knowing, mind, presence, time and space, causation, free will, belief in God, human immortality, etc.

Are there such questions? Empiricists like David Hume (1711-76), and many positivists, scientific naturalists, sceptics and others have said no.

METAPHYSICS? BURN IT. NOTHING BUT SOPHISTRY AND ILLUSION.

But the questions persist. To set them up and answer them, Western metaphysics has looked for foundations:-fundamentals, principles, or a notion of the centre. These are the groundings for all of its inquiries and statements.

This is the drive to ground truth in a single ultimate point – an ultimate origin. Derrida calls this impulse logocentrism. The logos is taken as the undivided point, the origin. Metaphysics ascribes truth to the logos, along with the origin of truth in general.

Metaphysics in its search for foundations is logocentric.

1 Use binary oppositions: cast the key terms against their opposites. If the question is being, establish “being” against “not-being”. And so on… presence/absence, mind/body, cause/effect, God/man, etc.

2 Privilege the first term: it’s the “groundly” term, the positive term, give it priority. It’s the term which articulates the fundamentals, principles or the centre. It’s on the side of the logos.

3 Subordinate the second term: it has to be negative, or the first term can’t be positive. It has to be deficient, lacking, corrupt, or just derivative. It opposes the logos, it is its enemy; or it dilutes that truth of truth, attenuates it, bleaches it out.

4 Set up a procedure: always move from the first term towards the second …

ALL METAPHYSICIANS PROCEED FROM AN ORIGIN, SEEN AS SIMPLE, INTACT, NORMAL, PURE, STANDARD, SELF-IDENTICAL … TO TREAT THEN OF ACCIDENTS, DERIVATION, COMPLICATION, DETERIORATION. HENCE GOOD BEFORE EVIL, POSITIVE BEFORE NEGATIVE, PURE BEFORE IMPURE, SIMPLE BEFORE COMPLEX, ETC. THIS IS NOT JUST ONE METAPHYSICAL GESTURE AMONG OTHERS; IT IS THE METAPHYSICAL EXIGENCY, THE MOST CONSTANT, PROFOUND AND POTENT PROCEDURE.

Derrida’s task is to undermine metaphysical thinking – to disrupt its foundations, dislodge its certitudes, turn aside its quests for an undivided point of origin, the logos.

It’s a major task. Derrida argues that metaphysics pervades Western thought. In a sense, it has been Western thought. Is it escapable? Has anyone escaped it?

I HAVE SOME ALLIES – NIETZSCHE AND HEIDEGGER ESPECIALLY; MAYBE FREUD, SAUSSURE AND OTHERS. BUT EVEN IN THEM I READ A RESIDUAL RELIANCE ON METAPHYSICAL ASSUMPTIONS.

So is this task possible? If metaphysics is so pervasive, isn’t Derrida’s own thinking going to be inhabited by it? Yes – inescapably. So the task is impossible? Derrida has never claimed that what he does is possible. He knows that no critique can ever totally escape from what it is criticizing. Meanwhile, movements can be made …

It’s always possible to OVERTURN a metaphysical binarism, to reverse its hierarchy by privileging its second term – for instance, to privilege body not mind, Man not God, the complex before the simple, absence rather than presence. Derrida does this. But…

TO DESTABILIZE BINARISM AND DISPLACE THE OPPOSITION ITSELF, I NEED SOMETHING THAT WORKS DIFFERENTLY.

Undecidability disrupts the binary structures of metaphysical thinking. It DISPLACES the “either/or” structure of oppositions. The undecidable plays all ways, takes no sides. It won’t be fixed down. It leaves no certainty of privileged foundational term against subordinated second term. The unfixing of this certainty is the unfixing of metaphysics.

Derrida’s philosophy has been called an anti-foundationalism. That’s partly useful. But Derrida is not simply “against” foundations, he knows they’re inescapable. However, metaphysical foundations can still be shaken. That’s what he does. He makes a movement of sollicitation (French, from old Latin sollicitare, to shake as a whole), a shaking at the core, a tremor through the entire structure.

Metaphysical oppositions rely on assumptions of presence.

The first or privileged binary term carries “full” presence. Its subordinate is the term of absence, or of mediated, attenuated presence.

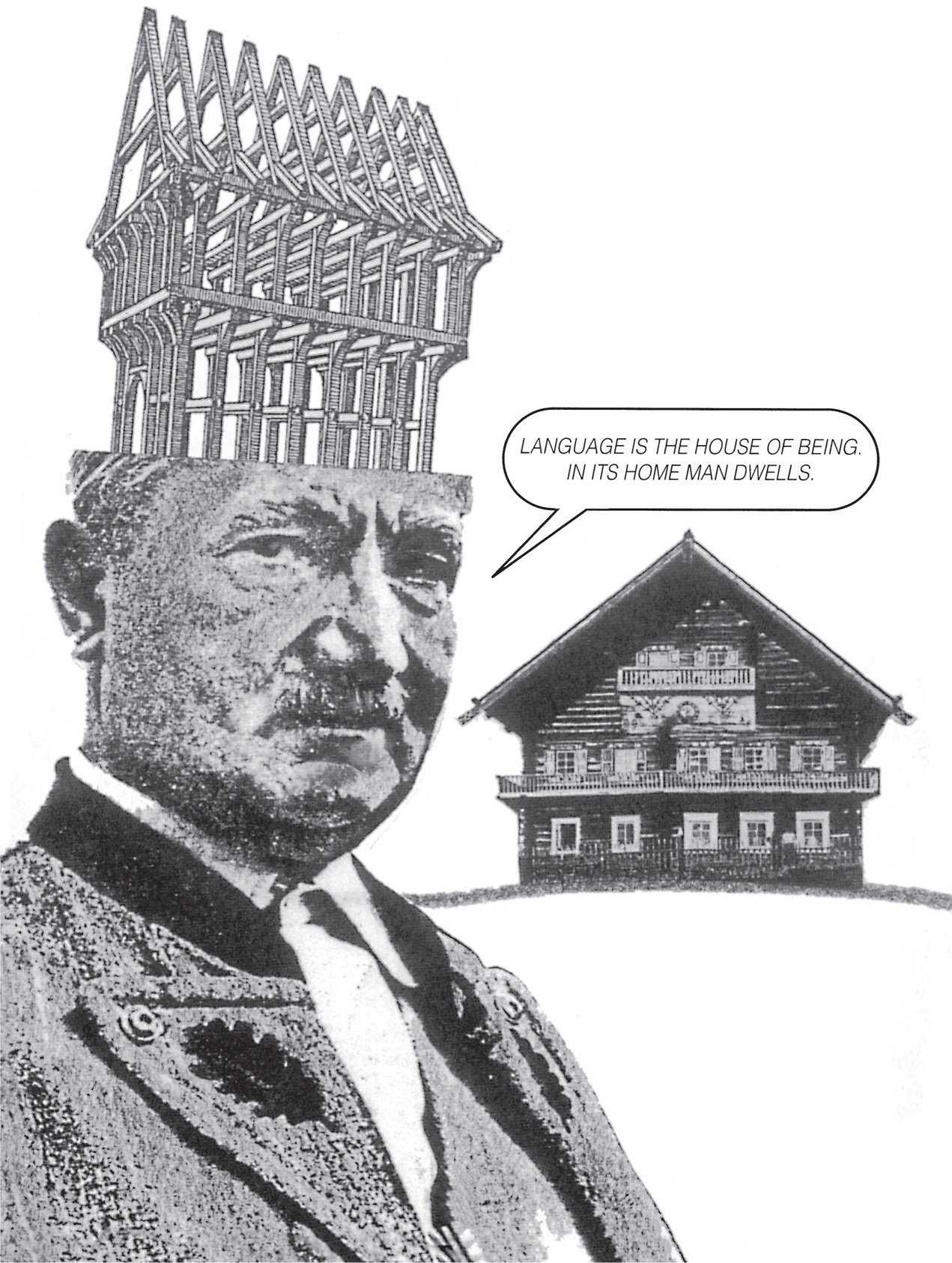

This is from Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), the German phenomenologist. Adopting Heidegger’s formulation, Derrida argues that in Western thinking the meaning of being in general has been determined by presence, in all the senses of this world.

PREOCCUPATION WITH THE QUESTION OF BEING LED ME TO REJECT MUCH OF TRADITIONAL METAPHYSICS.

Presence can be spatial: e.g. proximity, nearness or adjacency, and also immediacy – having actual or direct contact, lacking mediation, having no intervening material, object or agency.

And it can be temporal: it evokes the present as the single present moment, the now; and occurrence without delay, lapse or deferral.

MY INTENTION IS TO MAKE ENIGMATIC WHAT ONE THINKS ONE UNDERSTANDS BY THESE WORDS.

Presence organizes metaphysical concepts of being. And all the “groundly” terms of metaphysics designate a presence. Derrida’s examples …

– presence of the object to sight

– presence as substance, essence or existence

– temporal presence as the point of the “now”, or of the instant

– self-presence of thought or consciousness

– present being of the subject

– co-presence of the self and the other

PRESENCE IS AT WORK THROUGHOUT WESTERN PHILOSOPHY – ALL THE EMPIRICISMS, IDEALISMS, RATIONALISMS, REALISMS, ETC. PSYCHOANALYSIS, PHENOMENOLOGY AND STRUCTURALISM HAVE NOT ESCAPED IT.

Presence is the foundation for many claims, philosophical or not:-

• that a truth can lie behind (therefore in proximity to) an appearance

• that there is an immediate bond between the “word of God” and truth

• that a “spirit of the age” can inform an historical era, and therefore be present within it

• that a photograph can capture the “significant moment”, the now

• that an artist’s expressed emotion can be present in their work

Why, then, is the speech/writing opposition so important? Why is the privileging of speech a gesture which inaugurates Western philosophy? And if philosophy as we know it is writing, why treat writing as a corruption, an obstacle or an irrelevance?

BECAUSE IT’S A NECESSITY OF THE METAPHYSICS OF PRESENCE.

From that perspective…

Speech seems to carry full presence

Metaphysical concepts of being, in time and in space, demand presence.

Writing depends on absence

Its characteristics oppose presence. Metaphysical thinking has to eject it or subordinate it.

In speech, the speaker and the listener have to be present in at least two senses:-

A Present to the words in a spatial sense

B Present at a particular moment in time in which the words are uttered.

Therefore it seems that the speakers’ thoughts are as close as possible to their words. The thoughts are present to the words. So speech offers the most direct access to consciousness. The voice can seem to be consciousness itself.

Speech is transparent, a diaphanous veil through which we view consciousness. Speech and thought – nothing comes between them. No lapse of time, no surface, no gap.

So presence beguilingly seems to attend spoken words …

BUT NOT WRITING.

Writing operates on absences. As Derrida indicates, it doesn’t need the presence of the writer, or of the writer’s consciousness.

“The written marks are abandoned, cut off from the writer, yet they continue to produce effects beyond his presence and beyond the present actuality of his meaning, i.e., beyond his life itself.”

“To write is to produce a mark which will constitute a kind of machine that is in turn productive … The writer’s disappearance will not prevent it functioning.”

And the same for the reader.

“All writing, in order to be what it is, must be able to function in the radical absence of every empirically determined addressee in general… This is not a modification of presence, but a break in it, a ‘death’ or the possibility of a ‘death’ of the addressee. “

Writing cannot be writing unless it can function in these two absences. Presence is unsustainable.

The order of writing is distance, delay, opacity and ambiguity. And also death – “dead” meaning not the living meaning of a present speaker. “Written words, in a state of defenceless misery” have to be “abandonable to their essential drifting.”

So now we begin to understand the paradoxical phonocentric “history of silence”, that repression of writing which can scarcely be acknowledged.

And it begins to explain the disturbing tactics of Derrida’s own writing – its “difficulty”.

Derrida worked out the “speech/writing” problem across two dominant currents of French thinking: phenomenology and structuralism.

Phenomenology and structuralism are incompatible rivals – that was the prevailing view at the time. Let’s look at these rivals.

First, what is PHENOMENOLOGY? A “philosophy of consciousness” – neither intellect nor science can grasp the fundamental nature of consciousness. To do this, philosophy has to deal with phenomena – appearances and our awareness of those appearances. This awareness can’t be grasped through rational proofs and scientific data. What’s needed is intuition, a direct approach to the inner structures of consciousness itself.

BUT TO DESCRIBE THE FUNDAMENTAL EXPERIENCE OF THE WORLD NEEDS ATTENTION TO THE BODY, AND TO THE AMBIGUITIES OF EXPERIENCE. I FOUNDED THE EXISTENTIALIST JOURNAL “LES TEMPS MODERNES” WITH… FOR ME, PHENOMENOLOGY ISN’T A TOOL TO STUDY CONSCIOUSNESS. IT’S A MEANS OF REVISITING THE CENTRAL ONTOLOGICAL QUESTIONS:-THE HUMAN MODE OF BEING-IN-THE-WORLD, AND BEING ITSELF. PHENOMENOLOGICAL REDUCTION EXPOSES THE ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS OF CONSCIOUSNESS.

What is STRUCTURALISM? The study of human language, culture and society as structures. The elemental components of a structure are related to each other. So to analyze cooking (or economics, kinship, fashion, etc) examine its components in their relationships of difference, exchange, substitution. The ultimate model – language. Cultural and social structures work like language structures.

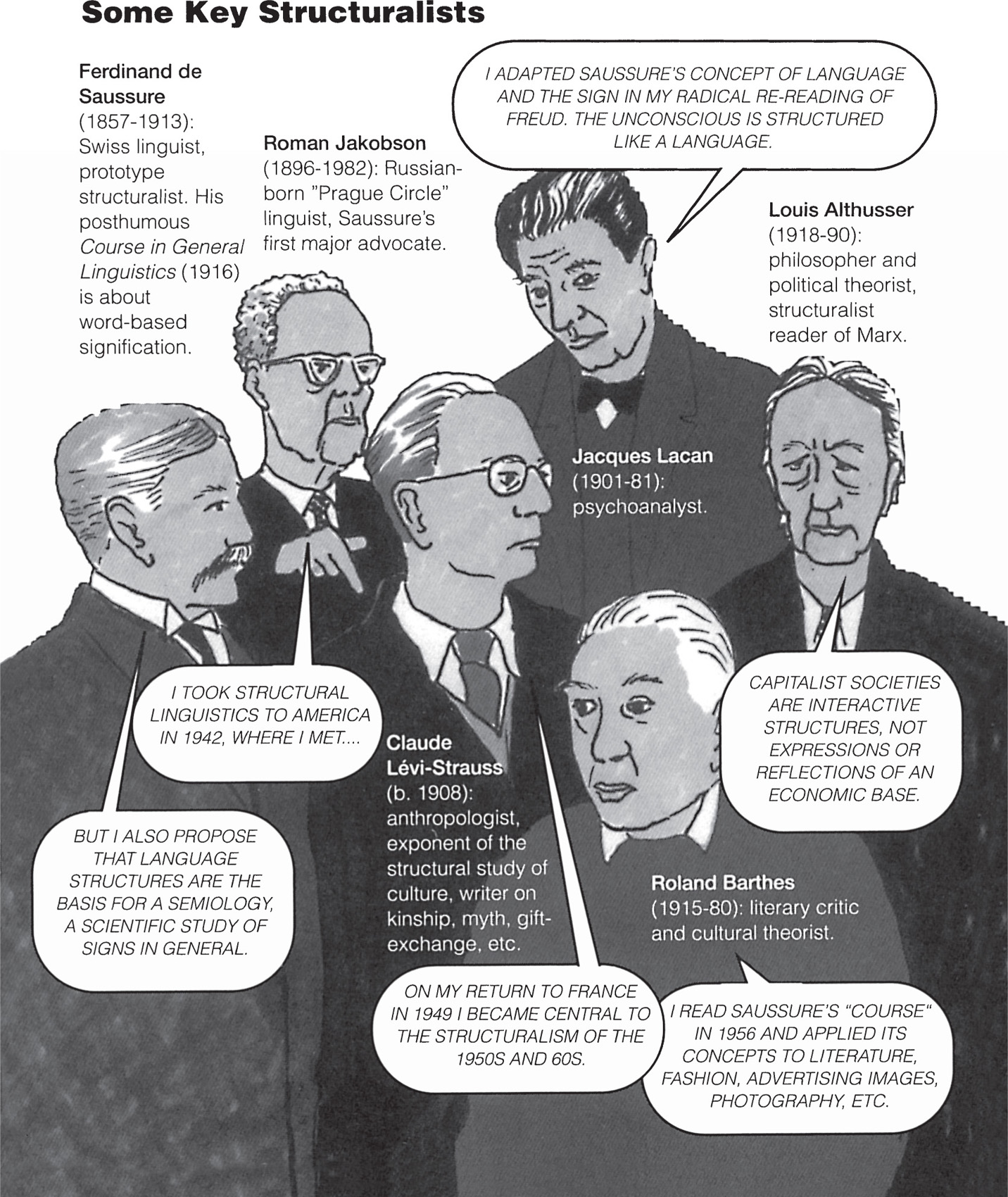

I ADAPTED SAUSSURE’S CONCEPT OF LANGUAGE AND THE SIGN IN MY RADICAL RE-READING OF FREUD. THE UNCONSCIOUS IS STRUCTURED LIKE A LANGUAGE. CAPITALIST SOCIETIES ARE INTERACTIVE STRUCTURES, NOT EXPRESSIONS OR REFLECTIONS OF AN ECONOMIC BASE. I TOOK STRUCTURAL LINGUISTICS TO AMERICA IN 1942, WHERE I MET… BUT I ALSO PROPOSE THAT LANGUAGE STRUCTURES ARE THE BASIS FOR A SEMIOLOGY, A SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF SIGNS IN GENERAL. ON MY RETURN TO FRANCE IN 1949 I BECAME CENTRAL TO THE STRUCTURALISM OF THE 1950S AND 60S. I READ SAUSSURE’S “COURSE” IN 1956 AND APPLIED ITS CONCEPTS TO LITERATURE, FASHION, ADVERTISING IMAGES, PHOTOGRAPHY, ETC.

There seemed to be irresolvable differences between phenomenology and structuralism.

They had different projects. Phenomenology is a philosophy of interior consciousness. Structuralism is a relational theory of language and culture.

And they had different conceptions of meaning. Meaning arises fundamentally in interior consciousness. Meaning arises in the relations between units of language.

But Derrida’s aim has never been to resolve anything.

IN BOTH TENDENCIES RELY ON METAPHYSICAL ASSUMPTIONS, THEY’RE ALREADY MORE SIMILAR THAN DIFFERENT. SO I USE ASPECTS OF BOTH TO UNDERMINE THE FOUNDATIONS OF BOTH…

Let’s begin with phenomenology. Can we hold out the possibility of a pure consciousness at the level Husserl wanted? Derrida argues that such a possibility is excluded at the very root…

Ideas Proper to a Pure Phenomenology

In his quest for the fundamentals of consciousness, Husserl had to expel everything that was merely local or contingent. Anything that belonged to particular individuals or situations was a matter of individual psychology. The fundamental structures of the mind had to be universal, transcendent.

His strategies:

AH, THIS IS MEANING PRESENT TO ITSELF. AT THE FOUNDATION OF THE UNIVERSAL STRUCTURE OF THE MIND, THE METAPHYSICS OF PRESENCE. AND THE WHOLE EDIFICE HAS TO RELY ON THE METAPHYSICAL OPPOSITION, INSIDE/OUTSIDE…

For Husserl, is there any way of thinking the relation between thought and language? Yes. And it’s governed by a binary opposition and a hierarchy.

The opposition: two kinds of sign:-

(a) EXPRESSIVE

(b) INDICATIVE

The hierarchy:-

The EXPRESSIVE sign is the properly meaningful sign, because it carries an intentional force, an intention to mean.

The INDICATIVE sign might signify, but it lacks this animating intention.

Examples of INDICATIVE signs:

Naturally occurring signs: the falling of leaves might signify “It is autumn”. But leaves don’t harbour intent.

FOR HUSSERL, THIS IS AN “INFERIOR, DANGEROUS AND CRISIS-LADEN SYMBOLIZATION“, BUT IT DOESN’T PREVENT MATHEMATICAL SIGNS FROM BEING PUT TO THEIR USES…

If living intention is to animate it, it will need the presence of its living producer. So, what’s the privileged form of the expressive sign? The speaking voice, superior to all other forms because it seems present (proximate, immediate) to the silent, interior consciousness. Husserl reproduces the phonocentric priority.

IN HUSSERL’S VIEW, TO EXPRESS ONESELF IS TO BE BEHIND THE SIGN …TO ATTEND TO ONE’S SPEECH, TO ASSIST IT ONLY LIVING SPEECH, IN ITS MASTERY AND MAGISTERIALITY, IS ABLE TO ASSIST ITSELF; AND ONLY LIVING SPEECH IS EXPRESSION AND NOT A SERVILE SIGN…

So what about the external supports of language – the marks, the sounds etc. which can be cut off from present intention, can go their own ways separately? To Derrida, these externals are always necessary and always inhabit the internal.

An encounter with Saussure’s structuralist theory of language became inevitable.

Saussure broke with previous approaches to linguistics. These had tracked the evolution of sounds and words across time. Saussure focussed on how language worked, not how it developed.

Language can be viewed synchronically, i.e., as if in a single moment. It can be seen as a structure or system, a set of elements located in relation to each other.

In structural linguistics, it’s the play of those elements and relations which produces meaning. For Saussure, this happens in two ways.

FIRST, MEANING IS PRODUCED IN THE FORMATION OF SIGNS AS TWO-SIDED ENTITIES. SECOND, MEANING IS ALSO PRODUCED IN A PLAY OF DIFFERENCES.

The “sign” has two aspects:-

A signifier: for Saussure, this is a sensory perception (a spoken word has an aspect we can hear; a written word, an aspect we can see).

A signified: a concept or meaning associated with that sensory perception.

A sign, to be a sign, needs both aspects: something we sense and something we think. It’s a relationship …

This relationship is nothing new. It’s the stock-in-trade of Western thinking about language. A sign has two aspects, one sensible and the other intelligible. Plato introduced the idea in his Cratylus, the Stoics formalized it, and it’s passed into modern linguistics via early Christian thinkers and others.

A SIGN IS SOMETHING WHICH, IN ADDITION TO THE SUBSTANCE ABSORBED BY THE SENSES, CALLS TO MIND OF ITSELF SOME OTHER THING. THE CONSTITUTIVE MARK OF EVERY SIGN IN GENERAL RESIDES IN ITS DOUBLE CHARACTER. IT IS BIPARTITE, AND HAS TWO ASPECTS: ONE SENSIBLE AND THE OTHER INTELLIGIBLE.

To Derrida, this is suspect. The sign is premised on a binarism and it looks suspiciously like a foundational concept in Western thinking.

“The difference between signifier and signified is no doubt the governing pattern within which Platonism institutes itself as philosophy…”

But Saussure’s sign might be useful to the critique of phenomenology. Especially, he emphasises that signifier and signified are indissolubly related. He insists that each requires the other – they cannot exist apart. Saussure conjures two metaphors. Signifier and signified are body and soul, or they are recto and verso of a leaf of paper. Saussure, choosing between them, prefers the sheet of paper. Its two sides are ultimately inseparable.

THE INVISIBLE, ALMOST NON-EXISTENT, THICKNESS OF THAT “LEAF” BETWEEN THE SIGNIFIER AND THE SIGNIFIED – A SIGNIFICANT METAPHOR, WE SHOULD NOTE, SINCE THE LEAF WITH ITS RECTO …

If Saussure is right, we can’t be lured into the notion that concepts or meanings exist independently of signifiers. Concepts need their physical sounds, their scripted marks, etc. Even if we can imagine words “inside our head”, we are conjuring their signifiers, their sensory aspects. Their external forms pollute the ideal of the purely internal.

So, for Derrida, this resists a classic move of Western metaphysics: the suppression of the signifier. The signified is the grounding term. The signifier? Inessential. It gets in the way, it corrupts the concept.

As with Husserl: evaporate the signifier and you’re left with pure thought – a “transcendental signified”. Where is this evaporation most complete? In the speaking voice, which seems to melt away under the force of the expressed consciousness.

But Saussure too falls back into this phonocentrism. What can be used to displace the sign?

Derrida uses Saussure’s concept of difference.

Meaning can’t be produced only in the binding of signifier to signified. It needs the operation of difference. How does this work, according to Saussure?

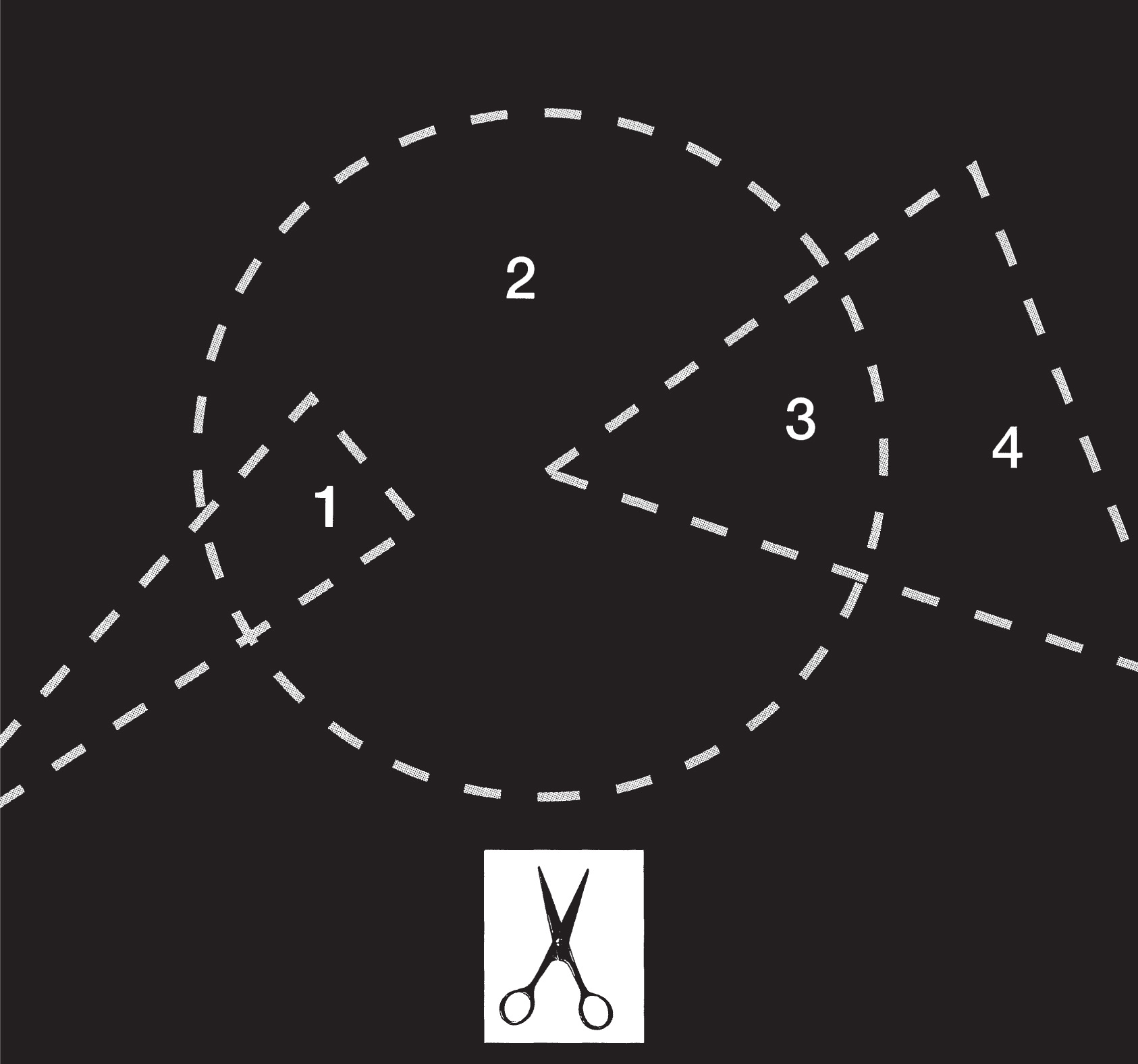

Saussure goes back to his “sheet of paper” metaphor.

If the sheet is cut into different shapes, one shape can be identified by its difference from the other shapes. That shape takes on an identity in relation to the others – it takes on a certain “value”.

In the cutting of the sheet of paper, the front and back have to be cut at the same time. The different shapes of the “signifier” side …

… make up the different shapes of the “signified” side Signifiers and concepts are created in a system of differences.

From this comes Saussure’s famous pronouncement – the structure of language is purely differential: “Whether we take the signified or the signifier, language has neither ideas nor sounds that existed before the linguistic system, but only conceptual and phonic differences that have issued from the system.”

Meaning is no longer simply a correlation of signifier/signified. Everything depends on differences.

At the level of linguistic sounds, we can substitute the sound /p/ for the sound /b/ in big.

The sounds don’t mean anything in themselves, but we can tell the difference between them. The difference makes possible a different meaning – the concept:

And so on, through other differentiable sounds and concepts:

etc.

And for Derrida this is a question of presence…

What happens when big circulates as a spoken word? The sound /b/ has to be spoken. No /p/, it would seem, is present. We will not hear the /p/, a speaker cannot say one at the same time. We might say, it is absent. But on the other hand, /p/ is not simply absent. Big, to be identifiable and meaningful, depends on it, and on all the other sounds from which it differs. Without /p/ and the others, it is lost. So the /p/ is in a way present, though not simply so. It is carried as a trace in the /b/, necessarily present in its necessary absence.

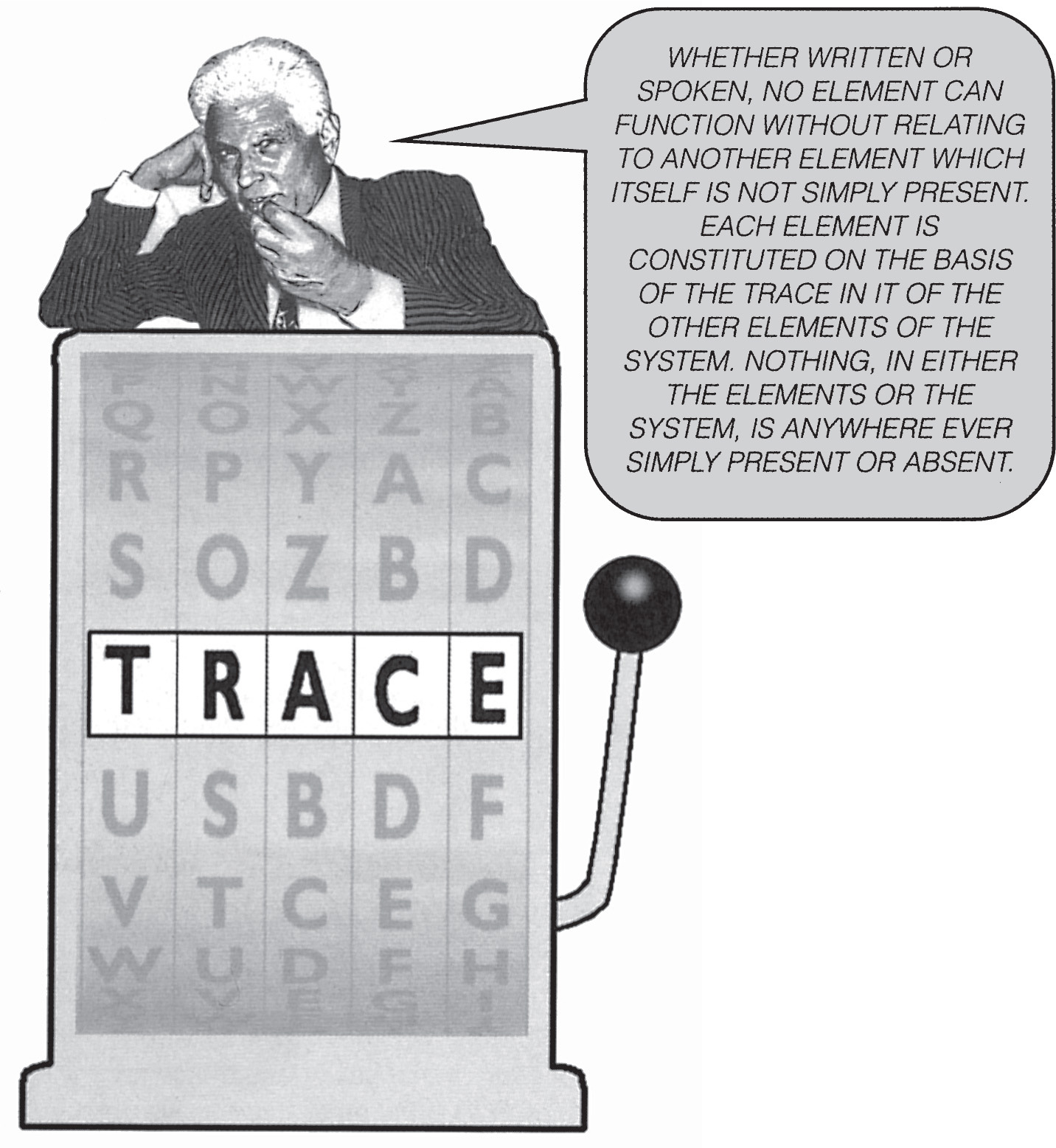

What does Derrida mean by “trace”? Neither simply present nor simply absent, the trace is an undecidable. The relay of differences (pig, big, bag, rag, rat, etc) depends upon a structural undecidability, a play of presence and absence at the origin of meaning. Undecidability at the “origin”, between presence and absence.

WHETHER WRITTEN OR SPOKEN, NO ELEMENT CAN FUNCTION WITHOUT RELATING TO ANOTHER ELEMENT WHICH ITSELF IS NOT SIMPLY PRESENT. EACH ELEMENT IS CONSTITUTED ON THE BASIS OF THE TRACE IN IT OF THE OTHER ELEMENTS OF THE SYSTEM. NOTHING, IN EITHER THE ELEMENTS OR THE SYSTEM, IS ANYWHERE EVER SIMPLY PRESENT OR ABSENT.

So Derrida sets the trace across the Saussurean sign – an undecidable presence-absence at the origin of meaning. Language is premised on an interweaving movement between what is there and not there. Language is always an interweaving, a textile.

What is the significance of Derrida’s notion of the trace?

First, it suggests that all language is subject to undecidability. The play of the trace is a kind of deforming, reforming slippage – an inherent instability which language cannot escape.

This applies to philosophical language as well. The vocabulary of metaphysics (being, truth, centre, origin, etc) has to be recognized as a vocabulary. It’s a set of words, and they cannot escape the play of the trace.

Now, if the trace is a constant sliding between presence and absence, those philosophical words cannot establish full, replete presence.

This strikes at the very roots of Western metaphysics, because it’s the claim to full presence which underpins metaphysical concepts and procedures.

Derrida’s writings on structuralism and phenomenology were published in 1967, in three books: Speech and Phenomena, Writing and Difference, and Of Grammatology. These were his first major publications, and they announced his complex assault on metaphysical thinking.

None of these texts offer arguments of the usual kind. They don’t simply refute, corroborate, commend or oppose. Rather, Derrida “makes a passage through” the texts of phenomenology and structuralism, searching out their hidden points of instability – the points where undecidability is at work.

In a sense, Derrida does the same thing with phenomenology and structuralism that he does with Plato and others. Reading their texts, he finds undecidables: the pharmakon, the supplement, the trace, etc. And he uses the undecidables to shake up the metaphysical foundations.

This helps to explain why Derrida’s writing can seem puzzling, infuriating or exasperating. To embrace the curious logic of this writing, we have to be willing to sign up to it, to subscribe to the task it takes on: the creation of destabilizing movements in metaphysical thinking.

Is this task as important or as necessary as Derrida suggests? Not all his readers have thought so. But to dismiss Derrida’s writing as wilfully obscure is too hasty. Understood as a rigorous unsettling of Western metaphysics, even Derrida’s most bizarre strategies begin to make sense.

Let’s look at two of these strategies: the use of palaeonymics and neologisms. Both exploit undecidability in the bid to undermine metaphysics.

To privilege writing over speech is one thing. But it’s not just a question of thinking the terms in their familiar opposition. Derrida re-conceptualizes writing as an undecidable: the play of presence/absence and radical difference, across speech as well as script. This is the play designated by Derrida’s terms the trace and the gram (hence grammatology). And by his term writing.

"WRITING” BECOMES A PALAEONYMIC: OLD WORD, NEW USES. IT NO LONGER DESIGNATES SCRIPTING RATHER THAN SPEAKING BUT RATHER THE UNDECIDABLE PLAY IN BOTH. IT INHABITS SPOKEN WORDS, INSCRIBED MARKS …

How can we tell when the word is used in this sense? We can’t. (Unless we add something, e.g. “writing-in-Derrida’s-sense”. But a supplement brings its own undecidability.) Derrida’s palaeonymy is a potentiality in all uses of the word, in his own texts and others.

Derrida also coins neologisms. Différance is one, and it doesn’t mean anything. It’s a coinage which can’t be exchanged…

Différance is not a French word. But it’s related to some words…

the noun

the verb

the verb-adjective

These offer Derrida’s neologism some possibilities. For instance, the verb différer has a play of both space and time: “things” differ spatially, “putting something off” is temporal.

And the same for the verb-adjective (“the differing shapes”, “the deferring tactic”).

But in French there’s a semantic deficit. There’s no noun-verb. We’d expect one – a word which lets us name the activity of “putting off”, or of differing with someone or something. If différance were a French word, it might be that noun-verb. But it isn’t. Not being that, it can supply the semantic loss and cover all other absences and occlusions of meaning across these related nouns, verbs, etc.

With this impossible possibility (différance is [not] a French word), Derrida inserts différance into four fields of concepts and words.

1 Insertion between speech and writing: Différance is pronounced the same as différence. If spoken, différance cannot be heard. But differance can be read. It privileges writing, while inhabiting speech as a possibility.

2 Insertion between nouns and verbs: Differance is neither noun nor verb. It plays between “thing” and “doing”, between entity and action:-a foundational opposition of philosophy.

3 Insertion between the sensible and the intelligible: Différance plays across both sides of the Saussurian sign (signifier and signified).

Let’s look more closely at the play of the sensible and the intelligible.

– Différance exceeds the sensible because the sensible needs gaps of time or space which are never fully apprehensible:-in speech, pauses and delays between sounds; and in script, non-phonetic signs, spacings on the page, little marks of punctuation, etc. We can see that two graphic marks differ, but we cannot see the difference. Differance encompasses this.

– Différance exceeds the intelligible, because the sensible inhabits the intelligible. As we see from the usual words for conceptualization. Derrida’s examples:-Greek theorein (theory) also means “to look at” or “to see”; French entendement (understanding) is the noun form of entendre, “to hear”.

4 Insertion between words and concepts: Différance is neither a word (in French) nor a concept (a signified). It doesn’t exist; it’s not a present-being, a “thing” with essence and existence. It refuses the question, “What is différance?”. Better to write: différance  Derrida crosses out the verb of being, putting it under erasure (“sous rature”: borrowed from Heidegger). Both there and not there, cancelled but not ejected, present and absent.

Derrida crosses out the verb of being, putting it under erasure (“sous rature”: borrowed from Heidegger). Both there and not there, cancelled but not ejected, present and absent.

Différance doesn’t follow the model of the standard philosophical neologism:- a (new) word for a (new) concept. Instead, it sets in play a movement of undecidability.

Différance is actively disruptive. Language, thought and meaning aren’t to be allowed the comfort of their daily routines. If that leaves philosophical language ruined, sick with its own instabilities, what about ordinary language and everyday communication? Can we rely on grounded decidability in the supermarket, the office and the lecture hall?

IT’S NOT IN THE DICTIONARY! MY AIM IS NOT TO JUSTIFY THE INVENTION OF THIS WORD BUT TO INTENSIFY ITS PLAY. EVERYTHING IS STRATEGIC, AND ADVENTUROUS. FOR THESE REASONS, THERE IS NOWHERE TO BEGIN.

Ordinary Language

To many of his critics, Derrida simply overlooks the fact of successful communication. Ordinary language works. Therefore it’s always possible – in principle, and barring accidents – to be clear, say what we mean, and to know what someone is thinking.

1971: the Sociétés de Philosophie de Langue Française organize a colloquium. The topic: communication. Derrida delivers a lecture, “Signature, event, context” in spoken words.

He sets up a question…

CAN THE WORD “COMMUNICATION” COMMUNICATE? PERHAPS, SINCE IT HAS A STANDARD AND ACCEPTED MEANING. COMMUNICATION IN LANGUAGE OR DISCOURSE IMPLIES A TRANSMISSION FROM ONE PERSON TO ANOTHER OF A MEANING OR A CONCEPT. IT’S A SIGNIFIED “IN TRANSIT” AND I TAKE ISSUE WITH THAT…

But there are other meanings. It can refer to a communicated movement – the transmission of a force, a tremor or a shock. Or it can mean a spatial passage by way of an opening or a corridor: e.g. a communicating door. In French, it can mean a conference paper (“Signature, event, context” is one of its meanings). “Communication” is polysemic: its signifier can relate to many signifieds. These threaten communication. How are they to be dealt with? “They permit themselves to be massively reduced by the limits of what is called CONTEXT.” And that, Derrida says, seems to go without saying.

“Signature, event, context” begins with context. How can a context assure “correct” meanings?

Derrida’s lecture had a context – a convention of French-speaking philosophers. Its communications are governed by consensus:

1. There will be linguistic communication.

2. It will be oral.

3. It will obey norms of intelligibility.

4. Agreement could in principle be established. And all this communication will be about language – not shocks and tremors, passageways, conduits, alleys, entrances, exits or conference papers. Nobody will write or mime or photograph; and the topic is not geological, etc. There will be proper communication about proper “communication”. And that goes without saying.

Can these proper communications be guaranteed by context, so nobody is in any doubt? Ultimately, can context master the play of differance and provide meaning with a safe haven from undecidability?

J. L. Austin (1911-60), Oxford “ordinary language” philosopher, believed there was a “safe context” for what he called performative utterances. He defined performatives in an opposition:

PERFORMATIVE utterances are speech acts which perform an action. To say “I name this ship the Argosy” enacts the naming: it is the naming, not a statement about the naming. Likewise with other performatives, such as those of marriage ceremonies.

CONSTATIVE utterances are assertions or statements of fact. “The cat sat on the mat” or “The practice of advanced capitalism is intimately linked with the practice of masculinism.”

CONSTATIVES CAN BE JUDGED TRUE OR FALSE – AND THEY’RE THE PREFERRED UTTERANCES OF PHILOSOPHY AND THE HUMAN SCIENCES. ALL PERFORMATIVES “DO THINGS WITH WORDS”, WHETHER MARRYING, PERSUADING, PROMISING, CLAIMING, INSISTING, BAPTIZING, COMPLAINING, BURYING, BETTING, GIFTING, OPENING, LAUNCHING…

Performatives aren’t true or false, but they can succeed or fail. This depends on context. Austin’s performatives need their correct context:

• a conventional procedure that everyone agrees to

• conventional and appropriate persons, words, and circumstances

• a conventional effect

And the procedure must be carried out correctly and completely by all. If all’s well, the speech act is “felicitous” (appropriate and perhaps happy). If not, something might not be performed, or it might be the wrong thing.

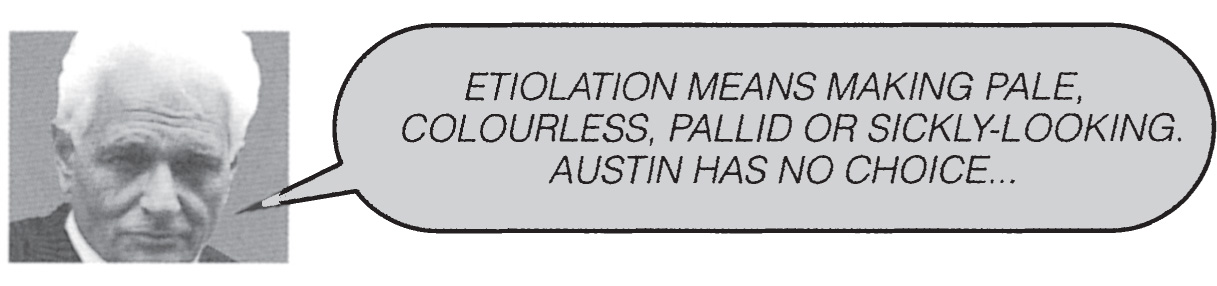

So performatives can fail. There’s worse: etiolation. Austin says:

“A performative utterance will be in a peculiar way hollow or void if said by an actor or on the stage, or if introduced in a poem, or spoken in soliloquy. Language in such circumstances is in special ways not seriously used, but used in ways parasitic upon its normal use – ways that fall under the doctrine of the etiolations of language.”

ETIOLATION MEANS MAKING PALE, COLOURLESS, PALLID OR SICKLY-LOOKING. AUSTIN HAS NO CHOICE…

“All this we are excluding from consideration. Our performatives are to be understood as issued in ordinary circumstances. I must not be joking.”

The fictional, theatrical and poetic – joking and non-seriousness. All this is blanched language, a pale imitation of its serious original. It is merely QUOTATIONAL, it simply REPEATS and RE-USES. Its performatives (and much else) are parasitical on the body of proper language.

Why does Austin exclude these? Because they are never intended to succeed.

Austin adopts the classic metaphysical procedure:-

1 There is SERIOUS language: it needs the presence of the speaker’s intention. A performative needs its context, correct to the last detail; and its last detail is its centre, its grounding – presence. The speaker has to have a genuine, sincere, present intention. Or the speech act will lose its proper colour.

2 There is NON-SERIOUS language: it quotes, repeats, re-uses the serious original.

AUSTIN CONJURES A KIND OF AGONY OF LANGUAGE THAT MUST BE KEPT FIRMLY AT A DISTANCE, OR FROM WHICH ONE MUST RESOLUTELY TURN AWAY. HIS ARGUMENT SUGGESTS A RISK SURROUNDING LANGUAGE LIKE A DITCH, INTO WHICH IT MIGHT FALL; A PLACE OF EXTERNAL PERDITION INTO WHICH LANGUAGE MIGHT NEVER VENTURE, THAT IT MIGHT AVOID BY REMAINING AT HOME.

Derrida views language differently. What Austin expels as aberrant, Derrida takes as the standard case. And this is found in writing. We’ve seen this already …

WRITING OPERATES ON ABSENCES. IT CAN BE CUT FREE FROM ITS SENDER AND ITS ADDRESSEE. IN THEIR ABSENCE A THIRD PARTY CAN DECIPHER IT, IDENTIFY ITS MARKS, AND USE IT.

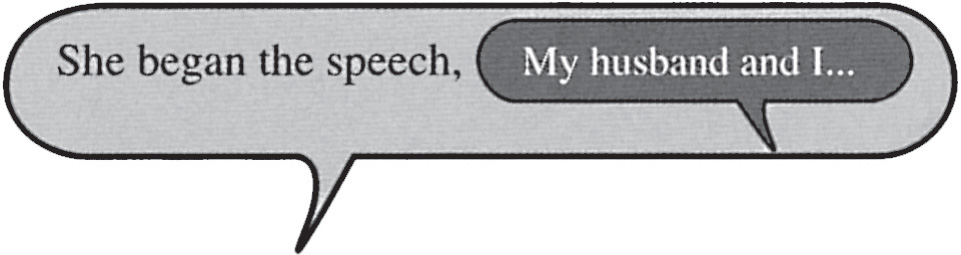

Writing must therefore be ITERABLE* – repeatable, but in the sense of repeatable-with-difference. We can repeat marks we can identify; and to identify marks, we have to be able to repeat them. We could not identify or read a writing we could not repeat. It would not be legible.

Iterability undermines “context” as a final governor of meanings. Repeatability implies repetition elsewhere …

Iterability has many implications. CITATION is always possible. We can always lift out a sequence of words from a written tract. We can make an extract, and it can still function meaningfully. GRAFTING is equally possible. We can insert the stolen sequence (whose property was it?) into other chains of writing. As Derrida writes: “No context can enclose it.” Hence writing is writing always with stolen words. Not to mention all of its quotations, plagiarisms, imitations, pastiches, etc.

THIS ISN’T CONFINED TO SCRIPT ITERABILITY, CITATION AND GRAFTING ARE FOUND IN ALL SIGNS, AND IN MY SENSE, THIS MAKES THEM ALL WRITING.

For instance, speech is iterable, citable and graftable. It’s possible to say:

It’s possible to cite oneself; and to make multiple embedded grafts. To say:

Speech, like writing, can be cut from its context, and from all the presences of its moments of utterance.

“What would a sign be that one could not cite? And whose origin could not be lost on the way?”

Derrida confronts us with a paradox. Repeatability is the risk of language, its ditch and its disablement. It can derail communication.

But repeatability is also its condition of possibility. Without it, there could be no recognizable signs. Without the possibility of a quotational version, we can’t have the “true”, “real” one.

Communication can be derailed by iterability, and it carries its derailer inside itself.

Derrida does not conclude that performatives and ordinary language lack effects; nor that the effects of speaking are merely the same as those of scripting. It’s simply that their effects do not exclude what is usually opposed to them: iterability, citation, and grafting. These cannot be expelled from language. They are its necessary condition.

Does this eradicate CONTEXT? For Derrida, no. There are contexts, but they have no centre and can never entirely govern meanings.

Does it eradicate INTENTIONS? Again, no. Iterability, citationality and grafting ensure that a force of intention will never be completely present in an utterance or its content. And it’s never completely absent.

INTENTION DOES NOT DISAPPEAR: IT WILL HAVE ITS PLACE, BUT FROM THIS PLACE IT WILL NO LONGER BE ABLE TO GOVERN THE ENTIRE SCENE AND THE ENTIRE SYSTEM OF UTTERANCES.

Communication? It is perhaps possible, if by communication we mean transactions which presuppose repetition-with-difference, quotation and re-insertions, without boundaries. And that could lead to some rethinking of everyday life.

There are signatures, every day. To Austin they are performative acts in writing. They follow his model. Legal signatures especially need an intending source present to the inscription in its moment of production. Signatures gain their power from this assumption …

PRESENCE IN THE NOW, STAPLED TO PRESENT PUNCTUALITY, IS THE ENIGMATIC ORIGIN OF EVERY PARAPH.

But Derrida sees the signature as writing. To function, it must be iterable: repeatable, imitable. It must be detachable from the signatory and the signatory’s intentions. There is no need for a particular intention at the point of signing.

Therefore signatures can be counterfeited, maybe fraudulently. This is necessary. To repeat “one’s own” signature (as if we could possess the marks) is always to counterfeit, to imitate. How else could we write the marks, would we know which marks to inscribe?

All of which makes the signature dubious. It’s always double, because always inhabited by the threat and the necessity of its repeatability. It could never give assurance if it could not be doubted.

The signature is doubtful. Does this destroy it? There are signatures, every day…

ITERABILITY IS THE CONDITION OF POSSIBILITY OF THE SIGNATURE, BUT IT IS ALSO THE CONDITION OF ITS IMPOSSIBILITY, OF THE IMPOSSIBILITY OF ITS RIGOROUS PURITY. ITS DETACHABILITY CORRUPTS ITS IDENTITY AND ITS SINGULARITY, DIVIDES ITS SEAL.

Derrida’s “Signature, event, context” ends with Derrida’s signature. He signs with an im/pure signature, a paraph and a re-mark.

What’s important in this argument about communication and signatures?

Derrida has argued that communication is always subject to iterability, citation and grafting. If so, it can’t be taken as a guaranteed, masterable passage of meanings. Language, Derrida says, is a “non-masterable dissemination”.

If that’s the case, we lose absolute assurance that we can “say what we mean” or “know what someone is thinking”.

I HAVE HERE A PIECE OF PAPER SIGNED BY HERR HITLER AND MYSELF…

We can’t even be sure who is speaking or writing: the identity of the author or signatory who appears to have produced the discourse, who’s signed for it, and who’s supposed to be – in the logocentric view – the origin or centre of the discourse.

Derrida derails communication, introducing disorder into its foundational concepts.

• Derrida’s texts aren’t located “outside” the texts they examine, in a position of attempted mastery or privileged authority. He doesn’t simply reject or oppose them. It’s more a strategy of inhabiting them, making a destabilizing passage through them, undoing their presuppositions and desedimenting them: stirring up their underlying levels.

• Derrida’s texts need their “host” texts. In a sense, they’re parasitical. The undecidables need the oppositions they disrupt. Yet the “host” texts already contain the elements which will undo them – Plato has his pharmakon, Austin his iterating etiolations – even if these are usually overlooked, denied, called to order, or given an eviction notice.

• Undecidability and derailments of communication are always and already at work, in all discourse – in law, politics, education, the military, medicine, etc, as well as in philosophy and theory.

Derrida’s task has been to intensify their disruptive play. His strategies and tactics have been given a name: DECONSTRUCTION. But in many ways, Derrida’s writing has scarcely needed it…

DECONSTRUCTION IS A WORD WHOSE FORTUNES HAVE DISAGREEABLY SURPRISED ME. I LITTLE THOUGHT IT WOULD BE CREDITED WITH SUCH A CENTRAL ROLE – IT’S BEEN OF SERVICE IN A CERTAIN SITUATION, BUT IT’S NEVER APPEARED SATISFACTORY TO ME. IT’S NOT A GOOD WORD, AND NOT ELEGANT.

Deconstruction?

Derrida had used the word in his early writings. It adapted and translated the German Destruktion or Abbau, terms Heidegger had used in his re-examination of metaphysics. For Derrida, the French word destruction was too negative and one-sided. It suggested antagonistic demolition or eradication. In Derrida’s uses, déconstruction designated a double movement: both disordering, or disarrangement, and also re-arranging.

First: any terms used to translate it – or to define it, by offering it definitive meanings or concepts – are themselves open to deconstructive operations.

Secondly, is there “something” to be defined or translated? Derrida resisted the suggestion that there is a concept of deconstruction, simply present to the word, outside of the word’s inscription in sentences and phrases determined by the undecidables. There’s no such concept simply to pass over into other words, other languages.

In Derrida’s view this is a problem for translation in general. Translators have to say, and not say, what someone has said.

Definitions and translations are always open to the classic metaphysical procedures, especially their ontological move: to determine being as presence. Deconstruction, Derrida suggests, might be better described as a suspicion against thinking “what is the essence of?”.

ALL SENTENCES OF THE TYPE “DECONSTRUCTION IS X” OR “DECONSTRUCTION IS NOT X” A PRIORI MISS THE POINT, WHICH IS TO SAY THAT THEY ARE AT LEAST FALSE. ONE OF THE PRINCIPAL THINGS IN DECONSTRUCTION IS THE DELIMITING OF ONTOLOGY AND ABOVE ALL OF THE THIRD PERSON PRESENT INDICATIVE: S IS P.

To name deconstruction is to call it to order, to harness it to familiar, stable, logocentric notions of what thinking should be. Surely, ultimately, deconstruction must be a mode of analysis or critique; or a method or a project. Derrida has resisted this.

It leads to “deconstructionism”…

Analysis seeks to distinguish simple, undivided elements which can then be treated as originary and explanatory. In its operations on Western metaphysics, deconstruction resists the move towards simple elements or origins.

Critique in the usual sense implies a stance outside its object. Deconstruction insists on movements across and between the metaphysical opposites, inside/outside.

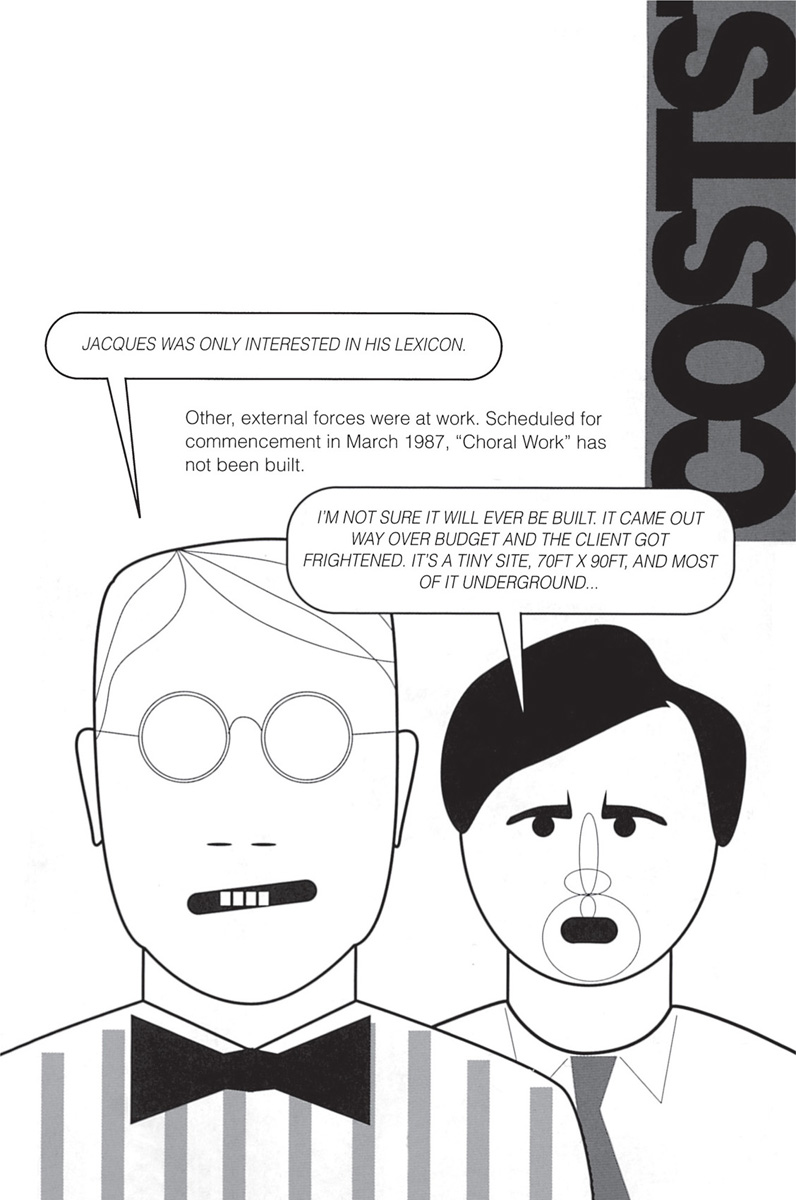

Method, in Derrida’s view, operates by selecting out certain terms of a discourse and using them to name something technical or procedural. He’s identified this especially in deconstruction in the United States, e.g. in aspects of the literary criticism known as Yale Deconstruction.

THIS LEADS TO DOMESTICATIONS, REAPPROPRIATIONS BY ACADEMIC INSTITUTIONS.

So as a last resort, can deconstruction be described as a project? Not if it has an outcome staked out in advance, a goal which predetermines its movements. Such a goal would govern foundationally. Deconstruction might clear pathways for its movements, but not knowing entirely where they lead.

Doesn’t this place deconstruction, and its adherents, in an impossible position, a “non-place” of contemporary thought?

I’D SAY THAT DECONSTRUCTION LOSES NOTHING FROM ADMITTING THAT IT IS IMPOSSIBLE; ALSO THAT THOSE WHO WOULD RUSH TO DELIGHT IN THAT ADMISSION LOSE NOTHING FROM HAVING TO WAIT. FOR A DECONSTRUCTIVE OPERATION, POSSIBILITY WOULD RATHER BE THE DANGER, THE DANGER OF BECOMING AN AVAILABLE SET OF RULE-GOVERNED PROCEDURES, METHODS, ACCESSIBLE APPROACHES. THE INTEREST OF DECONSTRUCTION, OF SUCH FORCE AND DESIRE AS IT MAY HAVE, IS A CERTAIN EXPERIENCE OF THE IMPOSSIBLE.

In 1967, Derrida concluded his essay “Structure, Sign and Play” by posing a question between two types of thinking. One dreams of deciphering a truth or origin which escapes play; the other turns away from the origin, and affirms play.

It’s a question maybe of choice – or in Derrida’s view, of the historical necessity of “relinquishing the dream of full presence”: the reassuring foundation, the origin and the end of play.

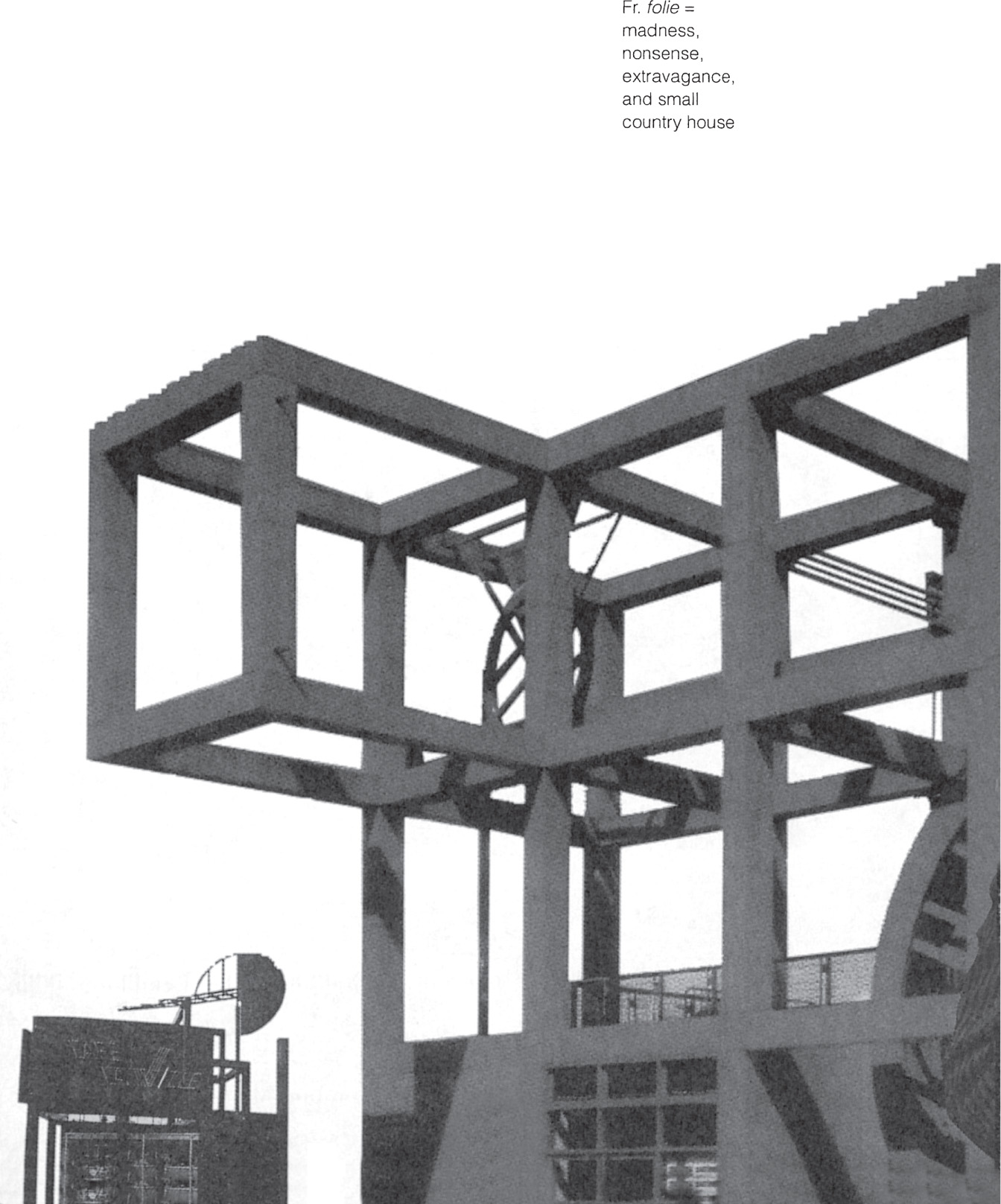

Unformed, monstrous, and perhaps unidentifiable, deconstruction has moved virally through fields beyond philosophy and theory. Derrida advanced its progress in architecture, art, politics and law. And especially, in literature…

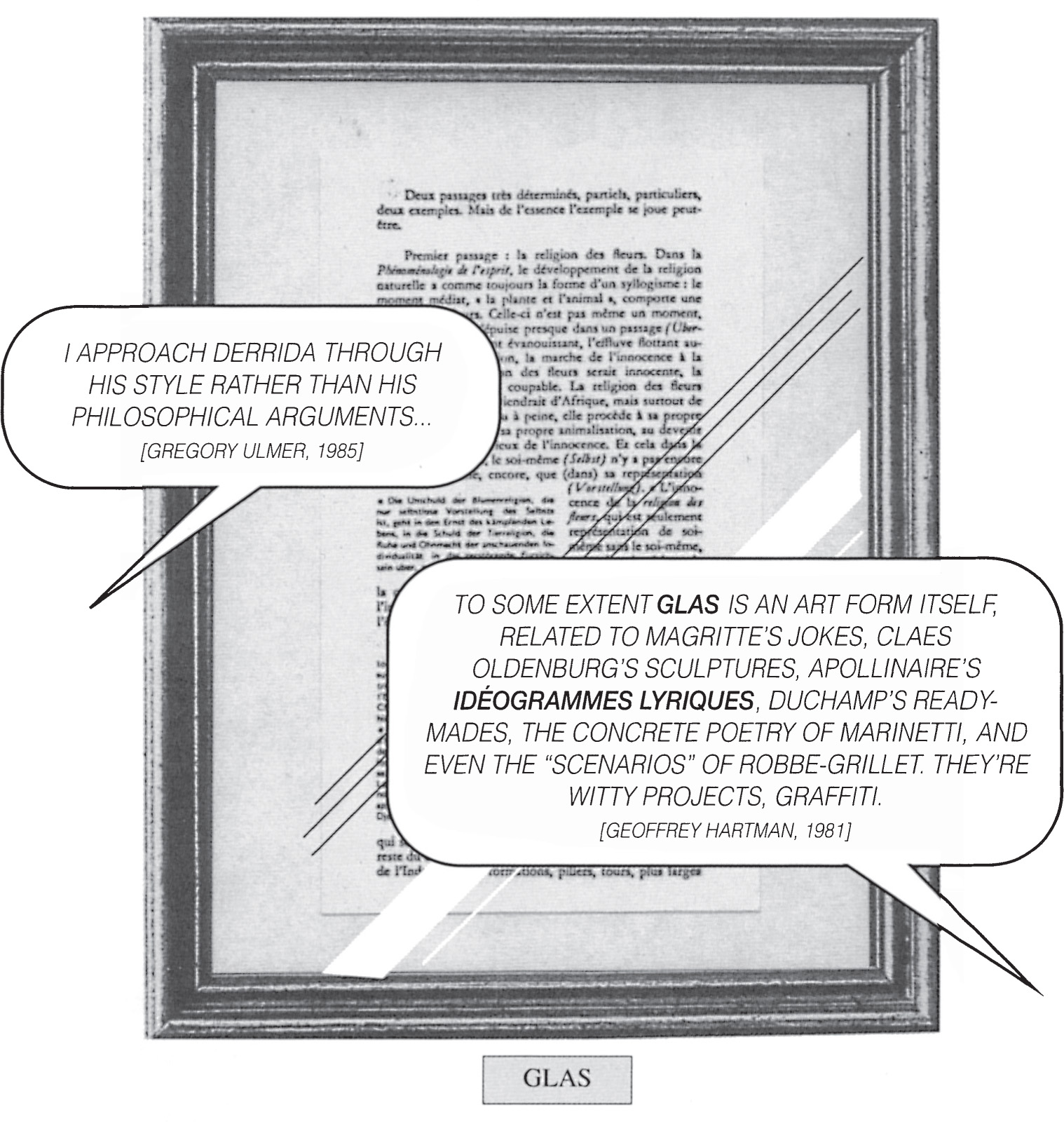

By the 1950s, philosophy and literature in France had new points of contact. The Surrealist poets of the 1930s had addressed philosophical issues. The novels, plays and poetry of Albert Camus (1913–60), Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–80) and others explored Existentialist themes. And Paul Valéry (1871–1945), Mallarméan poet and critic, saw philosophy as a practice of writing and therefore as a sub-category of literature. Derrida took a cue from Valéry. It is necessary to study philosophical texts like literary texts. We need to pay attention to their styles, forms, figures of speech – even their titles, layouts, and typography.

But traditionally, the philosophical search for truth has claimed precedence over literature’s concern with style.

Unlike Valéry, Derrida had little interest in simply OVERTURNING the hierarchical claims of philosophy over literature. He looked for ways of destabilizing or DISPLACING the boundaries between them, putting the categories themselves into question.

THERE’S NO ASSURED ESSENCE OF “LITERATURE” OR “PHILOSOPHY”. THEY’RE UNSTABLE CATEGORIES WITH NO GUARANTEES. IF THEY SEEM SECURE AND NATURAL, IT’S BECAUSE THEY’RE GOVERNED BY A POWERFUL CONSENSUS, PREMISED ON FOUNDATIONAL THINKING.

Their boundaries can never be entirely certain. Texts have traits, characteristics which they share with other texts. And a literary text can share some of its traits with philosophical, legal or political texts, etc.

Derrida exploits this. If the categories and boundaries are disturbed, the hierarchy too might begin to lose its grip.

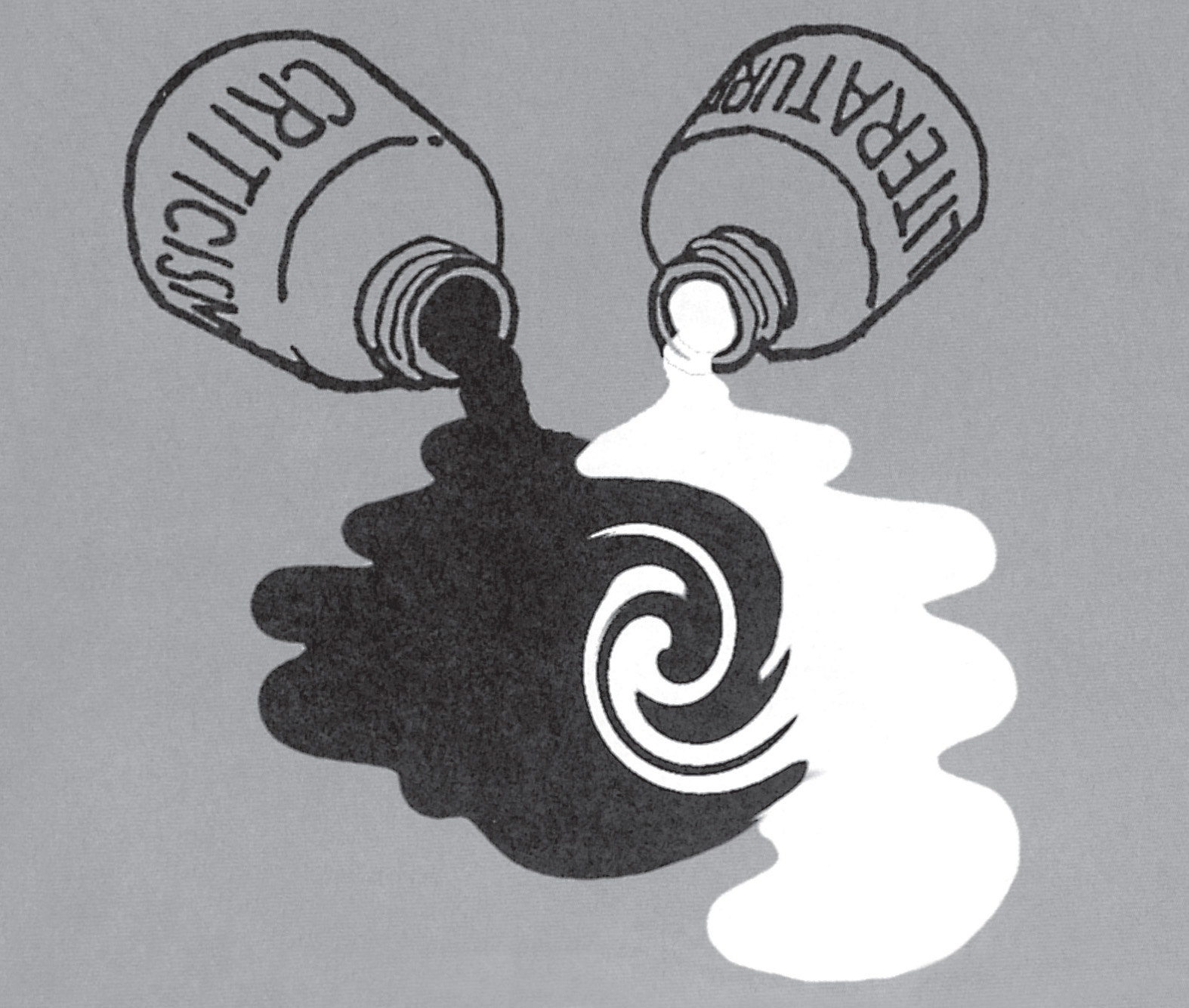

So Derrida opens literature and philosophy to a mutual CONTAMINATION. It’s a deconstructive strategy. Certain characteristics of philosophy and literature might remain, but they won’t be allowed an assured, overarching mastery of what is written and how it is read.

WHAT INTERESTS ME IS NOT STRICTLY CALLED EITHER PHILOSOPHY OR LITERATURE. I DREAM OF A WRITING THAT WOULD BE NEITHER, WHILE STILL KEEPING – I’VE NO DESIRE TO ABANDON THIS – THE MEMORY OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY.

What can philosophy gain from its own contamination? Studying literature can reveal something about philosophy’s limits of interpretation. That’s Derrida’s main interest.

He’s pursued it in two ways. He’s written about literary texts, though not producing standard literary criticism. But also, he’s borrowed devices and strategies from literary writing, and put them to use in his destabilization of metaphysics.

Searching out texts that have “made the limits of our language tremble”, Derrida has turned to avant-garde literature, to the modernist or postmodern writings of Mallarmé, Kafka, Joyce, Ponge, Blanchot and others.

In 1974 he wrote an essay, “Mallarmé”, for the series Tableau de la littérature française. It’s one of Derrida’s many engagements with texts by Stéphane Mallarmé (1842–98), poet and prose writer, modernist and Symbolist.

Mallarmé’s writing has usually been seen as a poetic exploitation of semantic richness – the potential of language for multiple meanings, references and allusions. Derrida reads it instead as a decomposition of linguistic elements, and especially of the word…

Mallarmé’s Or (Gold) plays on “or” as two letters, a syllable and a word. It’s all three.

Mallarmé has words of “gold”…

d’éclats d’or [gleams of gold]

dorure [gilding]

… but he also exploits “or” as letters inside words:

majORe [increase]

trésOR [treasure]

dehORs [outside]

hORizon [horizon]

fantasmagORiques [phantasmagorical]

Even as a word, “or” isn’t stable. It’s a noun (“gold”), but also an adjective (“golden”) and a conjunction (“now”):- “une éclipse, or, telle est l’heure” (“an eclipse, now, such is the hour”).

For Mallarmé the order of words is important. He often places “or” after “son” (“his” or “its”, a possessive adjective; but also the noun “sound”):-

“son or” (“his gold” or “golden sound”). Also, in French this sounds like “sonore” (= “sonorous”, an adjective).

He makes “son” hesitate between adjective and noun.

Especially, “le son or” can mean either “the golden sound” or “the sound or” – just the sound of the syllable, the oratorical material.

And Mallarmé, author of Les Mots Anglais, knew that “or” can be a syllable, or a word, or letters, in English or French.

This isn’t so much semantic richness as semantic indecision. And it arises from the unsettling placing of letters, sounds, words – from syntax (the location of linguistic elements) not semantics (meanings). In fact, it upsets, derails, meanings. Derrida’s interest is not the supposed rich content, the semantic luxuriousness, but the dislocation of content by strategic syntaxing.

This might work in philosophy too. Mallarméan syntaxing resists the assured content of crucial, foundational philosophical words like “truth”, “being” or “origin”. So Derrida decomposes words. Différance, neither noun nor verb (no word, no concept), undermines the stable order of meaning demanded by logocentric texts.

THERE’S NO NOUN, NO THING WHICH IS SIMPLY NAMED – IT’S ALSO A CONJUNCTION, AN ADJECTIVE, ETC. NO MORE WORD: ONE SYLLABLE CAN SCATTER THE WORD.

What has this to do with “Stéphane Mallarmé”? Derrida turns aside the usual questions of literary criticis. AUTHORSHIP, for instance. Can the author be present to the text, governing its meanings? Must we study authors? At the end of “Mallarmé”, Derrida recites the law.

ONE SHOULD HAVE SPOKEN OF STÉPHANE MALLARMÉ, OF HIS THOUGHT, OF HIS UNCONSCIOUS AND HIS THEMES, OF WHAT HE SEEMED TO WANT TO SAY. ONE SHOULD HAVE SPOKEN OF HIS INFLUENCES; OF HIS LIFE, FIRST OF ALL – OF HIS BEREAVEMENTS AND HIS DEPRESSIONS, OF HIS TEACHING, OF HIS TRAVELS, OF HIS FAMILY AND FRIENDS, OF THE LITERARY SALONS, ETC. UNTIL THE FINAL SPASM OF THE GLOTTIS.