Richthofen versus Two-Seaters

The Somme battle speeded Boelcke’s approach to air fighting. His new fighter squadron, Jagdstaffel 2, was listed on the books and staffed as of August 30 1916.1 Responding to the crisis atmosphere, the Air Service sent a full complement of brand new Albatros fighters within an additional two weeks. Boelcke attempted the complete unit’s first patrol a few days later (September 17) with a sweep directed towards the Cambrai vicinity. Richthofen was part of Boelcke’s group.

More than a beginner but less than truly knowledgeable, we might expect Richthofen’s career to follow the usual trainee path, one stressing the building of experience under a flight leader’s protective wings. However, there was no time for careful nurturing within the shadow of the Somme battle. Even this test-the-waters patrol soon stumbled upon a sizable formation of BE2’s rigged as bombers, protected by FE2b’s. In all, the Germans faced 14 British two-seater fighting machines. Boelcke’s awkward decision: attack or flee?

Boelcke’s flight of 5 pilots were of a mixed background. More to the point, none had significant Albatros fighter experience. Attacking a strong defense group with a raw flight team manning unfamiliar aircraft could appear unwise, and even foolish, to chair- bound Generals. Without a workable means of communication between pilots, attack could only result in an ‘every man for himself’ melee against a greater number of enemies, with each enemy likely to be more experienced. At issue was not only the fate of his men, but the future of an ingenious tactic – one based on employing fighting aircraft in specialized squadrons, each hopefully capable of wiping out enemy aircraft by the handful instead of the usual one at a time, now and then.

Nothing shakes an uncertain high command as does steep, unexpected losses at the very beginning of a new combat approach. If anything, the German Air Service had exhibited unusual risk taking ability in accepting Boelcke’s plans for separate air fighting squadrons. From the political/administrative viewpoint, avoiding severe losses in the opening phase of his planned expansion was the obvious move.

In short, common sense ruled against too early an attack; specifically those premature attacks conducted before the necessary lessons of aerial warfare were mastered. Many of the necessary how-to lessons already existed or would do so shortly. Only patience was required, permitting a gathering and learning process. However, Boelcke was a most impatient sort. He spent a few seconds, sorting odds, tactics and probability.

For example, how best to attack a FE2b? Why not simply employ the usual Fokker E-III method – the diving attack – as developed against the BE2 and other two-seaters?

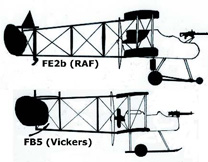

Though the FE2 and BE2 designs shared super-stability and an inability to dive steeply, their very different shooting arrangements separated their degree of vulnerability and suggested quite different forms of German attack as superior. Specifically, the pusher FE2b’s guns were arranged to face an attack from a similar or higher altitude – front or rear. The wide-angle opening and unlimited fire to the front is evident. Shooting effectively at enemies diving from the rear took some doing, but was soon mastered by the RFC.2

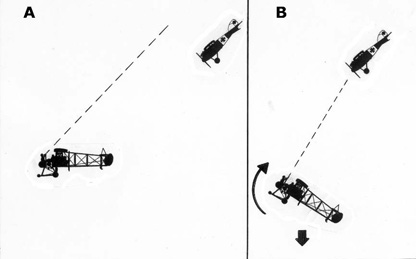

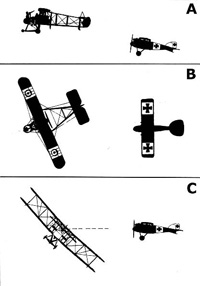

Diving Attack and FE2 Stall Defense

A standard attack (A) prevents gunner retaliation, for his field off fire is too limited. However, if suddenly stalled (B), the incidence change and altitude drop act to enlarge the gunner’s field of fire. He can then hit back at the attacker.Source: Original sketches by author based on 3-views Flight, June 28, 1917, p.619 and A. Fage & H.E. Collins Technical Reports of the Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, Reports & Memoranda # 305 (London: HMSO, Jan. 1917).

The deliberate stall ploy, used to open the field of fire to the rear, was a shrewd move but one with drawbacks. The resulting loss of both speed and altitude forced a stalling FE2 out of formation, and increased the likelihood of it becoming a straggler, suited for mopping up. Then there was the gunner’s nacelle itself, described by one gunner3 as: “[an] aerial footbath that hardly reached my kneecaps.” Precise shooting from so inadequate a source, all while standing within a howling wind was not easy – making the bringing down of enemies, especially those who were above and behind, an uncertain business.

Even so, Boelcke was impressed. He drew a careful, conservative conclusion: attacking an FE2b from above was not the optimum move. Instead, attack from below, and especially from the machine’s blind spot located at its bottom rear was much to be preferred. Once occupying this spot, the attacker was relatively safe and well able to pour bullets into the FE2b fuselage, located forward and above. He passed this on. Given this slender tactical advice, Richthofen was considered ready for the pressure of battle and need for reinforcements permitted no delay. Evaluating the odds and needs, Boelcke signaled his squadron to attack.

The action was instantaneous and vicious. Choosing an opponent was straightforward – nearest was best. Using his height advantage, Richthofen first managed a diving attack and “took my aim and shot. He [the FE2b gunner] also fired … and both of us missed our aim.”4 Richthofen then swung under his opponent to occupy Boelcke’s suggested back-and-below, blind spot position. Once there, he increased his nose-up attitude, risking stall, to be able to fire directly at his target. Moving as close as possible, his target was unable to escape. Also, when at a negligible range, shooting subtleties or counter maneuvers no longer mattered. The official5 combat report indicated that Richthofen “ … fired several times at close range … ten meters … [and] the enemy propeller stood stock still … ” The British two-seater descended in a long glide on the German side of the lines and it was all over. Richthofen had his first victory (September 1916), so excited by events that in landing alongside to gain confirmation, “I nearly smashed up my machine.”6 Both the wounded pilot and observer died before reaching medical aid.

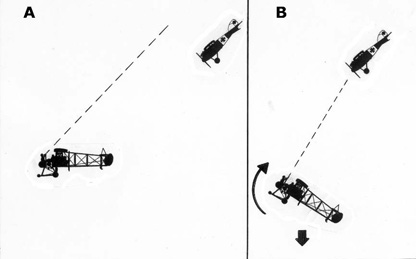

Once into the FE2’s blind spot behind and below – it was possible to open a surprise attack without immediate counterfire. Source: Original sketch by author from same sources used for image on previous page.

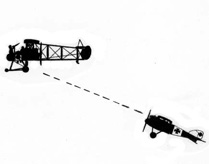

Shooting down an FE2b for his first victory (top), Richthofen incorrectly identified it as a Vickers Gunbus (bottom). Given the striking similarity, the error was understandable. Source: Original sketches by author from same sources as before and Flight, June 12, 1919, pp.760-761.

There was the usual confused upshot. Another German pilot staked a claim for the same downed aircraft. However, all parties finally agreed: it was really Richthofen’s victory. Then there was the matter of the downed aircraft’s ID. Richthofen claimed to have shot down a Vickers – but his badly shot about victim was obviously a FE2b. Here he was confused by the similar appearance of the two machines – further proof of his lack of experience.

Plagued by an unreliable engine, the Vickers ‘gunbus’ had a short and unsatisfactory combat career. At the time of Richthofen’s incorrect identification, the poorly regarded gunbus was no longer a significant combatant; however, it continued to exist in the imagination of propaganda artists, with a large sketch of a burning gunbus appearing in Flugsport, the semi-official German aviation journal just days before Richthofen’s victory. Widely studied by German Air Service personnel, this sketch may well have influenced his mistaken judgement.

Oddly enough, convinced that the FE2b was a Vickers, Richthofen remained unshakable despite official correction and his subsequent increasing experience. In all he was credited with twelve victories over FE2 type machines, a total that peaked many months later in 1917’s “Bloody April”. He identified most of these – incorrectly – as Vickers types.

Despite his increasing expertise, the FE2 was never an easy target. If anything, its many virtues made for a formidable opponent. This judgement was widespread; for example, RAF Marshal Sholto Douglas, at the time a two-seater combat pilot, rated the FE2 as one of 1916’s more useful fighting aircraft, though not the best – a position given to the Nieuport.7

This widely seen and easily remembered German propaganda sketch may have influenced Richthofen. Source: Flugsport , September 8, 1915, p.573.

Caught by an attacker occupying its blind spot, the FE2b’s best defense was a fast turn.8 Given a strong pilot, a quick turn could not only match that of an Albatros – just possibly losing him – but also forced a complex lead allowance shooting correction upon the attacker, likely preventing accuracy. It was straight ahead flight that offered a simple deflection allowance – turning alone could well be a good move, for shooting at a turning target was much more difficult.

Finally a turning FE2b, if given enough roll, permitted its gunner to see and hit an occupant of its old blind spot. Here was a potentially deadly counterattack, capable of destroying Albatros pilots too slow to assess the new FE2 prospects achieved by ‘turn and bank’ attitude.

To offset this form of FE2b defense, an attacking Albatros might shorten the range to near zero – as demonstrated in Richthofen’s first combat victory. However, this could be difficult to bring about. Granted a seasoned and fully aware pilot, the FE2 became a fast jinking, shifting, and circling machine impossible to approach closely. Fortunately for German attackers, the FE2 was usually burdened with a guard assignment limiting free-form maneuvering. Certainly, holding formation with bombers or observation machines placed severe restraints upon a defending FE2’s flight path.

In sum, a freely maneuvering FE2, in experienced hands, could well be a formidable foe. To an extent, Richthofen’s many FE2 victories followed from combat with enemy pilots deficient in either experience9 or awareness, or those too slow to abandon their guard duty responsibilities in order to defend themselves.

An FE2b could eliminate its blind spot sinecure (A) by a partial turn (B) taken together with a steep bank (C). The FE2b’s resulting change permitted it to shoot down enemies responding too slowly to the maneuver. Source: Original sketches by author from sources used for diving attack.

Another factor boosting Richthofen’s score was the superior gunnery available from his twin bolted down guns, as compared to an opposing FE2’s two-seater flexible Lewis guns. In principle a flexible (movable) gun would seem a more useful concept, with last moment changes in aim possible as dictated by the gunner. However, in practice, the many drawbacks associated with flexible guns prevented this hope.

One catch was the need for clearance between the moving parts of the flexible gun mount. Simple hinges or pivots required clearance between components – small spaces and gaps giving rise to the complaint of Sholto Douglas10 who saw himself as armed “with a rather wobbly Lewis gun … ” Decreasing the clearances eliminated the wobble and tightened the resulting shot pattern, but made gun movement – always hampered by wind pressure – that much more difficult.

A second disadvantage was the limited number of bullets available to most flexible guns before reloading was required. The pause while removing an old drum and inserting a fresh one could well mean a one sided – and fatal – halt to combat. Starting with a fresh drum and using the recommended 6 rounds per burst, the Lewis gunner had less than 8 bursts on tap. Furthermore, despite the 6 round recommendation, combat bursts tended to run long, resulting in perhaps only 4 or 5 bursts as truly available. These were few indeed. Typical air fights required many drums worth of cartridges – and much painful dead time while reloading.

As a final insult, in reloading the gun, a fresh drum could well be carried away by air blasts or simply dropped overboard, resulting in disaster. Taking all these disadvantages into account, the fixed gun’s larger supply of bullets, eliminating the need for reloading in the midst of combat, counted as an important advantage.

The German Parabellum flexible gun, developed years after the Lewis, reflected the greater experience available to designers by opting for a belt/spool cartridge arrangement offering 250 rounds. Thus, a greater ammo supply could be provided for flexible guns. The curse of the Lewis design was one of a total reliance upon the drum concept – useful in boosting independence – indeed, the gun could even be fired freely, offhand – but sadly limiting in terms of available bullet supply.

Though this pre-war Lewis gun was soon lightened and streamlined, its ammunition drum containing only 47 bullets – a severe limitation – continued in use throughout the war. Source: Hans Floerke, Deutchland in der Luft Voran (Munich: Muller, 1915) p.145.

A third flexible versus fixed gun issue was that of cooperation between gunner and pilot. In the case of the fixed gun, one man made all decisions, good or bad. For flexible guns, two men were usually involved – men who, while endlessly admonished to cooperate in their actions, were sufficiently human to frequently operate at cross purposes. Here, the lack of communication equipment was serious: hand signals, shouting and slaps had their limitations.

One disappointment in cooperation was that of vision and the sighting of enemies. Common sense suggested that “two men looking out”11 must be better than the one set of eyes available in a single-seater. Reality proved exactly the opposite: “two heads were worse than one.”12 To an extent the problem arose from laziness – that is, depending upon one’s partner to carry the load of searching the skies – and partly from the terrible FE2 sighting prospects available against those enemies employing an approach from the lower rear, behind the engine and propeller.

Another source of pilot and gunner cooperation difficulty was that of maneuvering in combat. To expect accuracy from an FE2 gunner while experiencing the stress of wild maneuvers was unrealistic: gunners needed a simple path offering a low G-loading to work effectively. Their pilots knew this, but were faced with the problem of forced maneuvering required to keep a canny enemy in sight. The solution required a truly shrewd pilot, able to anticipate his enemy’s moves and then fly an intercepting course offering the shooting opportunities of a steady path. As the FE2 was much slower than the Albatros or other fighters used by Richthofen, this ability to anticipate and head off German fighters was far from easy. Indeed, predictive, forward-looking tactics were well beyond reach for many of the poorly trained and therefore mediocre FE2 pilots. What could be offered by such pilots was energetic maneuvering, and this was done, despite the gunner’s curses.

Accommodating 250 rounds, the Parabellum employed a tricky belt plus spool feed plugged in at (A). Immediately under the gun is the bag used to catch spent cartridge cases. Source: Flugsport, January 1918, p.32.

When that rare combination of a gifted pilot and a skilled gunner flew as a combat team, the results could be impressive. In ace Captain James McCudden’s view: “A two-seater in which the pilot and observer cooperate well is more than a match for a scout … ”13 It was Richthofen’s good fortune to encounter few FE2 aircrews with the necessary skills. And of those who were skillful, still fewer achieved the proper level of working cooperation necessary to challenge his fighter.

A sense of the cooperation struggle may be gained from a single issue: which gun rules? In addition to the typical FE2 observer’s two Lewis guns – one for frontal use and the other mounted on a telescoping pole for rear or lateral use – the pilot had yet a third Lewis, capable of being fired to the front over the observer’s head. In principle, whichever gun was ‘on the attack’ controlled the priorities. If it was the pilot’s gun, the pilot was in total charge and could ignore his gunner’s needs. If the attack gun was one of the gunner’s, the pilot was to accept a supporting role, flying the machine to maximize his gunner’s chances.

Consider a frequently encountered combat situation. Let’s say that the gunner is engaged in attacking a frontal enemy when the pilot notices a number of fresh enemy machines diving on his rear. Is the pilot to continue aiding his gunner’s attack, or should he maneuver so as to prepare a strong defense? Which is most important here: attack or defense?

The official answer14 was both too subtle and incomplete: if the two-seater was about to experience a potentially overwhelming attack, then defense took first priority. An example was given: should the number of fresh attackers amount to three, then certainly defense came first. Fine, but suppose there was only one fresh attacker? What then? How was the judgement to be made concerning whether the fresh attack was of the truly threatening type, and so deserved full attention? Under what circumstances was the gunner’s attack on a frontal enemy to be abandoned in favor of immediate defense?

Officialdom offered nothing. It was all up to the aircrew. Inevitably, pessimistic aircrew members would see even one attacker as threatening, and optimists would not. Dissension and working at cross-purposes was certain. Instead of a practical resolution, RFC instruction15 pointed to the happier, if “rare”, times resulting when an FE2 would be able to dive on an enemy formation, “the pilot picking a lead machine and the gunner a following machine.” In this way, two enemies could be attacked with one FE2. Well, yes.

The issue of gun jams further burdened aircrew relations. Certainly prevalent, two-seater reactions varied widely. At one extreme were the views of FE2 NCO gunner Arch Whitehouse. Starting as a ground force machine gunner trained to take apart and assemble Lewis guns until he could do so blindfolded, he automatically took whatever remedial action was necessary to clear stoppages. As a result, he flew Western Front combat missions for many months, enduring much combat and earning important decorations, all without a single “serious gun stoppage.”16 Given his unusual background, he was unable to sympathize with anyone experiencing of “a serious delay” in gun operation.

Few shared his training and subsequent good fortune. In particular, student pilots carried too full a schedule of flight instruction and were given little time with guns. As a result, many FE2 pilots were initiated into combat lacking the ability to cure jams. Gunners themselves varied widely in their training and ability. Most learned that taking remedial action in class was one thing, while doing so in the air under enemy fire was quite another. With their lives hanging in the balance, contempt and fury for a partner unable to take instantaneous corrective action was inevitable.

Richthofen had experienced exactly this form of aircrew dissension. Earlier in his career, serving as a two-seater gunner, Richthofen had fired and missed at an easy target. His previously friendly pilot,17 “reproached me for having shot badly, and I reproached him for not having enabled me to shoot well.” Equally bad British aircrew cooperation was a factor in many of his subsequent victories.

Even well functioning aircrews learned that some cover was necessary for time out of action. Should a gunner’s Lewis jam or need a drum changing, FE2 pilots were encouraged to use the dead time to “either attack, or defend the machine by maneuver.” Hopefully, the pilot was to attack using his own gun, for “a vigorous attack by the pilot is the best cover.”18

If the pilot’s gun was out of action, the recommended maneuver was to kick the rudder back and forth. This legs-only process freed the pilot’s hands for work on the gun. Simultaneously, the gunner was to fire “accurate shooting, or not”19 to mask the unavailability of the pilot’s gun. For those highly skillful pilots able to direct the control stick with their knees, a better move was to bank and turn sideways,20 offering a difficult target while freeing both hands for gun correction. Exactly this procedure was standard for the Fokker E-III.

With so much depending on the ability to fire at will, and gun jams prevalent, the possibility of using paired or twin guns was investigated. It was hoped that if one jammed, the other would be available. Twin gun advantages were real, and certainly the doubled firepower of paired fixed guns was important in combat. However, it would be learned that the foggy, freezing weather likely to jam one gun would likely jam its twin: gun duplication was only a partial answer.

For Lewis guns, pairing was generally unsuccessful. The resulting high gun mass slowed any desired shifting of the aiming point. Replacing two drums at a time was a severe nuisance. The greater air drag of the gun combination was also a negative point and most gunners agreed with Flt. Lieutenant F.M.M. West, who “preferred the single Lewis, as I could maneuver it with much greater ease.”21 As a result, twin Lewis guns were rarely employed.

Granted two fixed guns, Richthofen’s fighters were usually opposed, not by the combined firepower of a FE2b’s three Lewis guns, but by whichever single Lewis happened to be pointed in the right direction. To further increase the odds in his favor, Richthofen made use of the FE2b gunner’s inability to fire accurately while maneuvering. Of the three guns, the one pointed upwards and rearwards was especially sensitive to airspeed and acceleration, for its gunner stood smack in the center of a high-speed slipstream. Shooting backwards while stalled at a low airspeed was one thing and worked well enough to be a serious option; however, firing accurately when engaged in a high-speed maneuver was quite another matter. Even the RFC conceded that “ … once the machine [FE2b] can be forced to dive or stunt, the gunner can’t stand up and use his gun.”22

To Richthofen the proper tactics were clear: encourage the FE2b to dive. At best, the dive itself would be of a shallow type, easily overtaken by his own fighter. Furthermore, with the gunner out of action owing to wind, a subsequent attack from the above/rear was not only safe but likely to be profitable. It remained only to induce the FE2b to dive.

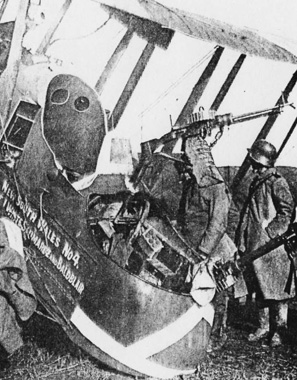

A downed FE2b offers the standard Lewis gun on post (A) for lateral and forward shooting, plus a second Lewis (B) for shooting towards the front. A third Lewis–the pilot’s gun– has been removed. Source: Luftfahrt, October 1917, p.22.

There were ways. Much depended on FE2b aircrew fear and ignorance. One way was to open fire prematurely, at too great a distance and altitude. As much of the fighting occurred on the German side of the frontlines, within a few miles of the front, there was always a British hope of escape by fleeing across the lines to safety.

The concept of a safe zone for the British was backed by Boelcke himself,23 who preferred the much greater profit gained by bringing down Allied aircrew members as prisoners – those flying on the German side of the lines – as compared to those brought down on the Allied side. The latter were mostly men who would fight again another day; however, if taken prisoner they were truly out of the war. This view discouraged German fighting machines from pursuing enemies across the Allied lines. More than a philosophical wish, orders were issued to this effect in 1916. Interviewed after the war, Hauptmann Carl Bolle, a member of Boelcke’s squadron, said, “At the Somme, the pilots of single-seaters were expressly forbidden to cross our lines.”24

With his Blue Max award prominent, Boelcke poses for one of his last photos. Source: AVIA (Netherlands) November 1916, p.207.

To a set-upon, hapless FE2b pilot bent upon fleeing to safety, and desperately trying to increase his exit speed, diving seemed best. To cover ground in a hurry, jinking and maneuvering were dropped – straight line flight was faster. This worst possible combination played into Richthofen’s hands, for the resulting high-speed shallow dive prevented accurate rearwards shooting from a fleeing FE2, and the straight line flight path eliminated Richthofen’s problems of gunnery lead and deflection. To profit from FE2 limitations, it was only necessary that he create sufficient panic, leading to a desire for escape above all.

In using this process, as compared to close-in fighting, Richthofen expended many times more bullets. Many of these were fired to produce fear, rather than damage, and were fired from so great a distance that accuracy was impossible. He preferred it that way. True, his first victory had resulted from extremely close range and only a few bullets, but given some thought, he decided that close range was overly dangerous – a few well-aimed rounds might find him or, and far more likely, collision might result. As he put it: “I had gone so close that I was afraid I might dash into the Englishman.”25

He had learned a profitable lesson: better than a struggle at 10 meters range was a distant engagement with a fleeing, diving FE2 located some hundreds of meters away. More profitable was a contest between a soft target unable to shoot back effectively, opposed by his twin fixed guns and a full complement of bullets – many hundreds of bullets. Given these conditions, it was just a matter of time and bullets until Richthofen triumphed.

In achieving FE2b victories, Richthofen officially reported expended bullet counts ranging from 200 to 300 to 400 and even 800 cartridges. Reflected was not sloppy shooting, but shrewd tactics: it was much wiser to win by expending too many bullets at a long range than by employing too few bullets at a close range.

Boelcke’s October 1916 death through collision with his own wingman in the midst of combat – occurring within Richthofen’s sight – reinforced the point. Flying in proximity to either friends or enemies had strong drawbacks. Yes, there were times when nothing else would work, but with the FE2b as enemy, other tactics were equally successful and much safer.

For one, deliberate loss of surprise when attacking could sometimes be useful – even against those FE2b pilots too wise to flee. Instead of attempting to sneak up on an enemy aircraft unseen, in the hope of inhabiting its blind spot, it could be profitable to announce one’s presence by opening fire when far out of range. Experienced enemy pilots would then most likely settle into a circular pattern; one offering a sound base for maneuvering, and a difficult target as well. However, owing to circling, the always low FE2b speed over the ground was cut to almost nothing. The result was to make it that much easier to catch up with the FE2b. True, the enemy pilot had been alerted and warned that a fight was impending, but his near-zero ground speed meant that he was unable to reach a nearby safe zone, or friendly aircraft, or anti-aircraft guns. Richthofen’s gain consisted of isolating the enemy. At times, when the sky held many British machines, the singling out process was profitable, despite its loss of surprise.

Thus shooting at an ultra long range had its uses, but when under pressure and shooting for destructive effect, Richthofen preferred to open fire at the close range of 50 yards.26 Most gunnery experts preferred 100 yards, and RFC advice suggested even 200 yards as suitable.27 Given Richthofen’s concern about collision, why 50 yards rather than 100? There were some clear gains: for one, bullet spread was smaller as the range closed, increasing the probability of multiple destructive strikes on an engine or fuel tank. There was also a gain in accuracy, for smaller values of the always uncertain deflection allowance were necessary. Finally, a new and most useful factor promoting accuracy entered: tracers.

On exhibit in Berlin as war booty, little damage is to be seen aside from the bashed-in nose, likely received upon its final landing. Source: Luftfahrt, March 1917, p.18.

Over great distances, tracers could be misleading. Optical illusions28 arose to mislead and infuriate users. However, at his preferred short range of 50 yards, tracers accurately described bullet path. So perfect was its portrayal that deflection allowance and even gunsights could be ignored – instead, all aim was controlled by what was seen. In a fast changing gunfight, where no man could think quickly enough to do the necessary calculations required by deflection allowance, tracers were a superb solution. As for the short range necessary to make tracers practical, Richthofen was willing – after all, 50 yards was much safer than the 10 meters he had come to fear.

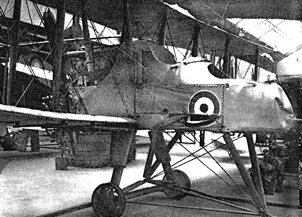

Even as Richthofen learned to cope with the well-regarded FE2, other two-seaters came under his guns – especially the ever plentiful, and generally despised BE2. When hunted by the E-III back in 1915, it proved an easy victim. Yet, unlike the Fokker, late versions of the BE2 managed to hang on, surviving to see the war’s end. Though a poor fighter, other BE2 features were precisely those wanted in an artillery machine – it could land almost anywhere and had superb visibility. Especially well-liked as a long range reconnaissance machine, and fairly capable as a light bomber, it was too good a machine to discard.

As for fighting, there was always the hope that one those endless revisions of BE2 Lewis gun mounts might produce a winner – a machine able to shoot effectively – permitting survival when sharing the same sky as Richthofen.

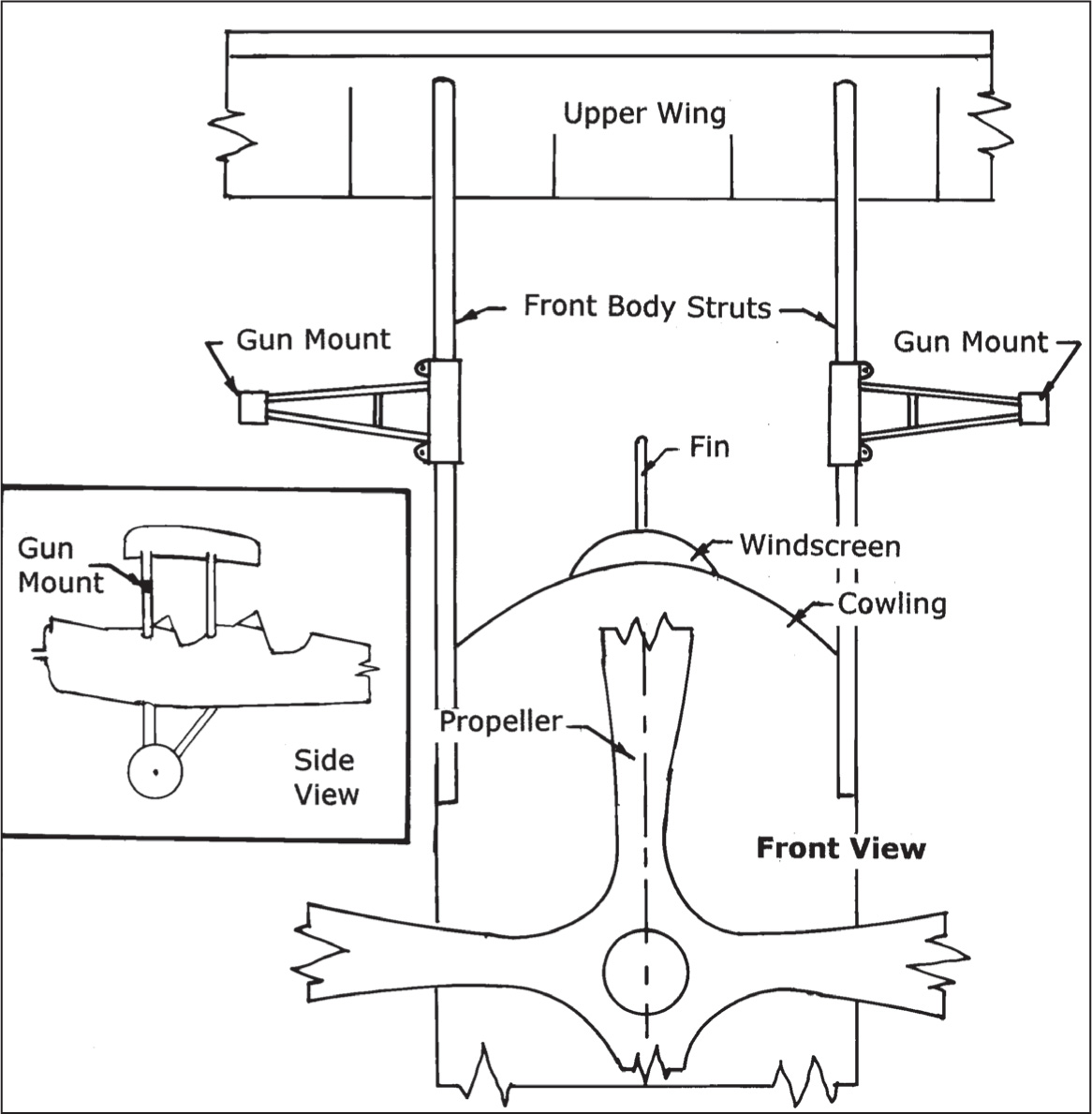

Shown is one more gadgeteer’s approach to shooting in the frontal direction. As given previously, the problem stemmed from that enormous four bladed propeller; efficient but offering severe blockage to shooting forwards. Lacking an interrupter, it was necessary to shoot at an angle to miss the propeller. This time around, the shaky “trellis” gun mounts have been eliminated in favor of mounts bolted, high up, upon the wing struts. Forced to stand, the gunner fired at a safe, proper angle and then if required, transferred his Lewis gun between mounts as a frontal enemy aircraft passed from side to side. The advantages claimed were those of greater mount rigidity and a smaller aiming correction, owing to a decreased oblique aiming angle.

Though a poor fighter, its simple, sturdy lines and superb vision helped it serve effectively as a light bomber and artillery observer. Source: Claude Graham-White and Harry Harper, Air Power (NYC: Stokes, 1917) p.241.

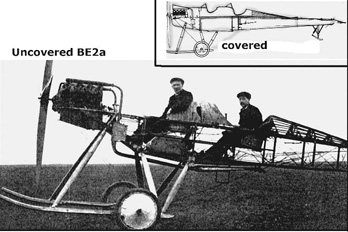

(main illustration) Uncovered fuselage skeleton with gunner up front and pilot in back; (inset) covered, largely with cloth. Sources: (main) F.W. Lanchester, Aircraft in Warfare (NYC: Appleton, 1916) plate 4. (inset) original by author.

One more “Christmas Tree” design change for the BE2c, supposedly permitting improved shooting at frontal enemies. Source: Original sketch by author based on official working drawings TNA file # AVIA 14/5/2/33.

Drawbacks included: (1) the necessity for the gunner to stand with his upper body doused in the propeller blast; (2) the low shooting accuracy obtainable from any form of angled fire; and (3) the need for transferring the Lewis gun from mount to mount in the midst of action. Even RFC officials came to view the endless mount designs with contempt. For example, RFC General H. Trenchard upon inspecting a similar gun mount commented, “I never saw such ridiculous nonsense.”29

Though shooting to the rear eliminated the propeller blockage problem, experience pointed to other difficulties, ranging from the distraction produced by shooting directly over the pilot’s head, to occasional hits on the rudder or elevator. All things considered, many aircrews preferred lateral shooting, despite serious problems in estimating deflection allowance. In shooting to the side: (1) the gunner was able to crouch down, avoiding some of the air blast; (2) he was less likely to hit his own aircraft, over-excited or not; and (3) shooting took place a few feet distant from the pilot, rather than a few inches away, permitting him to concentrate upon flight rather than offer a cringing inattention.

In all, the BE2 was much inferior to the FE2 as a gun platform. While the FE2 had severe limitations, especially when shooting to the rear, it did offer superb frontal shooting. The BE2 was handicapped, front or rear, by blockage, propeller blast and gun mount problems that permitted no easy solution. The use of the FE2 as a fighting escort for the BE2 – rather than the reverse – was reasonable, for the FE2 was the better fighting machine. As confirming experimental evidence, consider Richthofen’s 1916-1917 comparative victory count: 17 BE2’s downed, as compared to 12 FE2’s.30

In weighing these numbers, it should be noted that Richthofen’s mode of fighting led to more BE2 than FE2 combat opportunities. To frontline infantry troops, nothing was as infuriating as flying enemy artillery observers, carefully correcting the aim of cannon located far behind the lines. It was this very role – artillery observation – that employed most BE2’s. Sometimes they were guarded by FE2’s, but sometimes not. Determined to eradicate observation machines operating near the frontlines, Richthofen’s chosen path would come across many more BE2’s than FE2’s.

As a secondary factor in Richthofen’s victory count, the BE2 was simply easier to shoot down. Even the BE2’s lateral shooting gimmick had a painful drawback, one important enough to be fully detailed by the RFC.31 Rather than actually fly parallel to a BE2, and expose themselves to lateral shooting, canny German attackers would feint doing so momentarily – for periods of a few seconds. The idea was to persuade the BE2 gunner to set up his Lewis for lateral shooting, all while the attacker swung around to sit on the BE2 tail. Of course, the exasperated gunner would then move his gun to a mount suited for shooting to the rear – but this would take still more time. In the opinion of the RFC, the time required “to react and realign the gun – perhaps 30 seconds” gave the attacker his “best chance.” Given the usual machine gun cyclic firing rate of 10 rounds per second, and taking into account necessary pauses, the thirty second delay made possible the safe firing of more than one hundred bullets – enough bullets to decide the fate of many BE2s.

Even if a BE2 gunner was set for a rear attack, German fighter pilots soon learned a means of outwitting the defense. Rather than the usual direct attack employing a shallow dive, it was much wiser to dive vertically some distance away – too far for accurate defensive shooting from the BE2. Given the extra speed picked up in the dive, it was then possible to close in quickly under the BE2 tail, where its gunner vision and accuracy were poor, while those of the German fighter were fine indeed.32

Richthofen’s combat reports33 supplied highlights of his BE2 victories. His words were limited to unusual happenings, with ordinary fighting viewed as too humdrum to record. Even so, many of his tactics were revealed, as were those of the opposing RFC.

His first BE2 victory (# 8 of his 80-victory total) was gained over a machine attempting a light bombing mission, as signaled by the absence of a gunner. Here the desperate need for an increased bomb load led to eliminating the gunner to save weight, making it that much easier to down. Of all possible BE2 arrangements, the no-gunner version was the German fighter pilot’s choice. However, such opportunities were rare.

More typical were victories # 19 and # 20, over BE2 machines carrying gunners. Here he was able to approach closely, unobserved, and open fire from his favorite 50 meter distance. When one of these targets proved inert, the result of a lucky early hit, he moved closer – to a distance of one aircraft length – and continued shooting. Given the right circumstances, his concern over collision was set aside. In this case, the BE2’s inert behavior convinced him that there would be no erratic last moment maneuvers, and that a close approach was safe.

When a BE2 showed the presence of a gunner and plenty of life, but was cursed by a hapless desire to flee in a straight line, Richthofen employed his favorite FE2 tactic. Following at a great distance, he would fire many bullets in the belief that despite his range-limited accuracy, sheer numbers and better ballistics would win. In effect, he was betting his life on the supremacy of twin fixed guns as compared to the BE2’s single flexible gun. He found the process to be both safe and generally victorious. To gain victory # 22 against a fleeing BE2, some 500 bullets were required. Essentially the same was true of # 29.

Long range shooting was not always the answer to those who fled. Some BE2 pilots attempted to use their flying skills to get down to tree top level and play a hide and seek game. Here the idea was to discourage the aggressor, for the game was equally dangerous to the prey and the pursuer – one wrong move and collision with a tree or house ended the game. Those pursued hoped that their aggressors would give up the chase – and many did – as not worth the risk.

Richthofen was well aware of his own limits as a stunt pilot. He had little natural feeling for aerobatics and for the most part flew mechanically, though with great determination. In the case of victory # 32, determination carried the day: his target, an observation BE2, flew into the ground when a tricky on-deck maneuver failed.

The rest of his BE2 victories, told in similar reports, indicate that his earlier lessons remained intact, with successful techniques used repeatedly. Typically, those attacked were artillery observation machines carrying a gunner, with the actual attack occurring near the frontlines. Always balancing the collision prospect against the needs for accurate shooting, Richthofen would approach closely if his target appeared unaware. If wide awake, he would open fire at a greater distance. Close or far, his twin fixed guns spelled the end for most of his BE2 victims, either through wounds or aircraft damage.

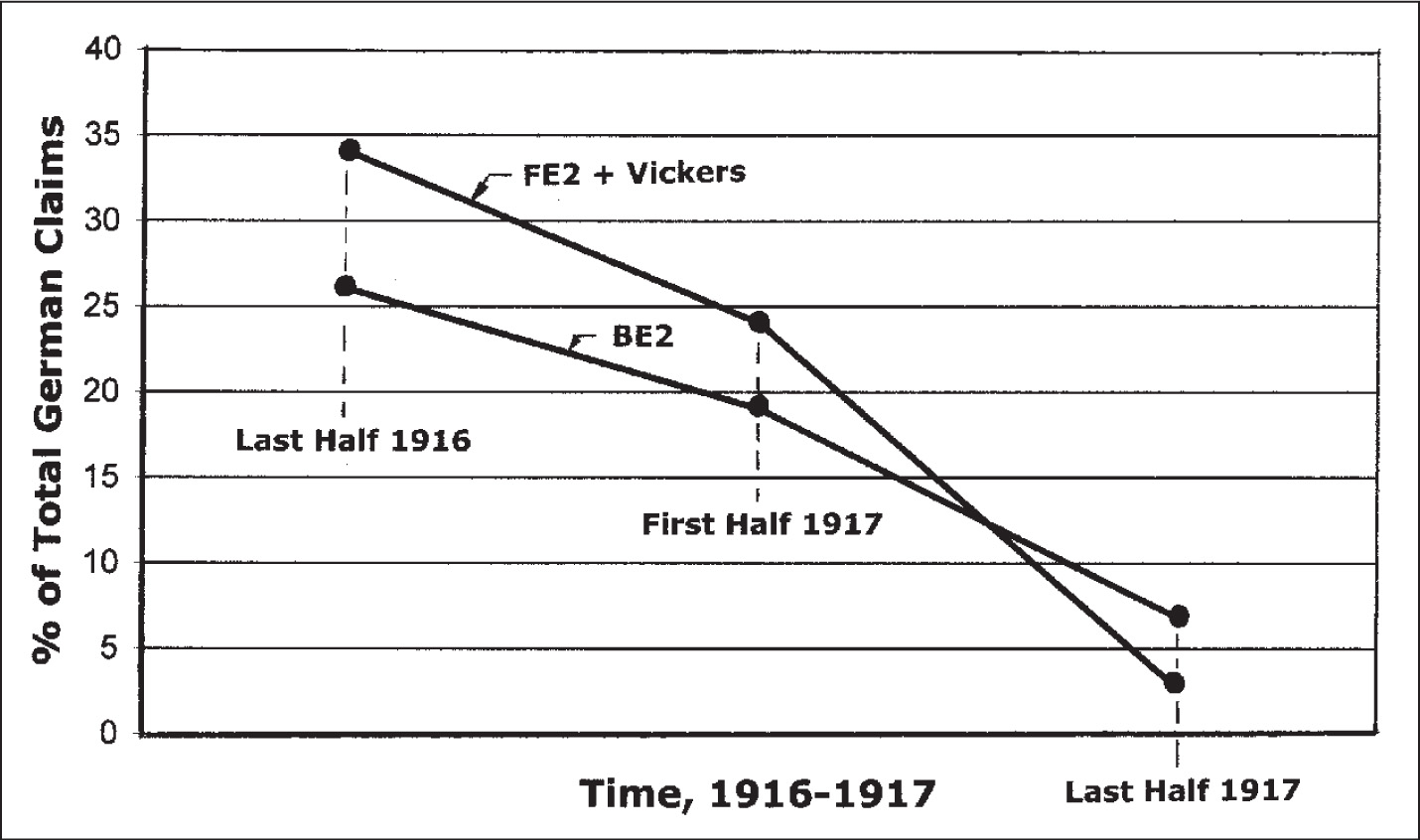

Moving into 1917, total German claims for downed FE2 and BE2 aircraft fell sharply as older types were replaced by newer designs. Source: Original plot by author from data, Luftfahrt, October 1918, p.16.

Next Generation RFC Two-seaters

Despite improved performance and armament, they continued to fall victim to Richthofen’s usual techniques. Source: Original sketches by author based on 3-views, Flight, February 6, 1919, pp.170-171, Flight, January 23, 1919, pp.102-103.

Over time, and especially after “Bloody April” of 1917, Richthofen’s victories against both the BE2 and FE2 slowed and stopped. Richthofen hadn’t lost his touch. Instead, having developed other two-seaters believed to be superior, the RFC had reduced the number of older two-seater types operating on the Western Front. The natural result was to cut all BE2 and FE2 losses sharply, as shown, and push Richthofen into a new learning cycle, centered upon the new machines.

Not only did the new two-seaters vary in their fighting abilities, but Richthofen’s aircraft were updated as well. In effect, the same two-seater versus single-seater struggle continued, though it was played with new aircraft on each side. This time around, some of the RFC two-seaters had fixed, forward firing machine guns as well as the usual flexible Lewis guns. In another major switch, Richthofen’s continually improved Albatros and Halberstadt series machines were traded in for the Fokker Triplane – a business of exchanging fast and furious aircraft for one that was slow and maneuverable. Inevitably, combat was influenced.

Did combat against two-seaters really change? Not really. Consider the Sopwith 11/2 Strutter. At last able to shoot through the propeller, it offered the pilot a bolted down Vickers gun complete with interrupter. In addition, the gunner was given a Lewis gun set within an effective rear circular turret. Taken together, the resulting design would seem a sensible, upto-date shooting combination. Yet in downing his first 1½ Strutter (victory # 23), Richthofen successfully used the same “long range + too many bullet technique” evolved to deal with the FE2. Once again, Richthofen fired 400 bullets towards his opponent34 and the battle was over. His combat reports describing subsequent victories over 1½ Strutters (# 33 and # 38) offered no fresh tactical insight other than an account of attempted Sopwith evasion. Certainly, any RFC fighting aircraft whose defense was limited to evasion smacked of hopelessness – something was wrong.

A sense of the Sopwith 11/2 Strutter problem was offered by RFC pilot Captain Balfour.35 Carrying only 110 h.p., its performance was “vastly inferior to the Albatros in speed, climb and maneuverability.” As for the updated gunnery aspects, they counted for little when measured against the deficient performance. Finally, when in a high-speed dive, “at above 160 mph, the wings were liable to come off.”

Against such a monstrosity, Richthofen had little incentive to develop new fighting tactics – his old methods worked just fine. Oddly enough, this remained the case even when the opposing two-seater was a fine machine. None was better than the Bristol Fighter, equipped with a 200 h.p. Rolls-Royce. As with the Sopwith, the rear gunner had an effective turret for his Lewis and the pilot was given a bolted down Vickers. Able to climb to a fighting altitude of 10,000 feet in 11 minutes, as compared to the 11/2 Strutter’s 19 minutes, it offered a speed of 113 mph once there – some 10 mph more than the Sopwith.36 In short, both a good performance and a solid platform for gunnery were offered by this rarest of wartime designs – one sound enough to survive the war and soldier on for many more years.

When a Bristol Fighter was encountered in March 1918, Richthofen opened with his usual long range shooting approach and was startled to see the gunner fire only straight upwards and then disappear from sight, presumably scrambling about for something on his cockpit floor. Offering no defensive fire, the aircraft was easily forced down. Only when about to land did the gunner emerge to offer a few defensive rounds. Of course, it was too late; and so, victory # 64 went to Richthofen.37

Bristol Fighter versus Fokker Triplane

The Triplane (upper right) opens fire in a shallow diving attack–a tactic frequently employed by Richthofen. Source: The Aeroplane, January 15, 1919, p.192.

There were encounters with yet other new breed two-seaters, including the RE8 and the Armstrong Whitworth. Yet, to the end, Richthofen remained satisfied with his old two-seater tactics – those developed in 1916 against inferior aircraft. Subsequent RFC aircraft modification was all very well, but the results did not offset the many disadvantages inherent in the RFC approach to two-seater combat.

Summing up, his quickest way to victory remained an unseen close approach, followed by execution with a few bullets. If the victim was too alert to permit this possibility, a long range fight against the gunner’s single Lewis gun would do as well, though at the expense of many bullets. Here Richthofen was betting on the superiority of his bolted down guns with a relatively huge ammunition supply, as against the uncertainty of flexible gun aiming made worse by the painfully limited number of bullets contained within a Lewis supply drum. These gunnery factors, heavily favoring Richthofen, remained unchanging throughout the war.

Yet another factor that changed but little was the relative lack of experience displayed by many of his opponents. The British training system produced many pilots, but these low-time graduates usually lacked the expertise necessary for combat. Also produced were too many gunners unable to cope with simple gun jams. Inevitably these men and their machines became, if not Fokker Fodder, then Richthofen fodder.

Single-seater combat, with its promise of one against one offered a greater challenge to Richthofen – one where the numerous two-seater drawbacks were no longer a factor. Skill, speed and maneuverability were the deciding factors. Richthofen was ready.