Richthofen versus Scouts, 1916

Richthofen’s introduction to combat had gone well, ending with the destruction of an opposing British two-seater. He had been fortunate in his background, consisting of much flight experience in equivalent German two-seaters. As a result, he knew what to expect of his opponent – the stately maneuvers and performance limits he encountered offered no surprise.

Scout combat was sensed as quite different. Knowing his own Albatros, he could grasp scout capabilities and regretfully, his own limitations. He found aerobatics difficult and gossip had it that aerobatic skills were crucial to success. It was certainly true that putting a scout control stick into the hands of Immelmann made for fancy aerobatics and that Immelmann had achieved stunning success. Cause and effect? Coincidence?

The world loves a romantic, swashbuckling hero. In a war made grim by poison gas and mud-filled trenches, it was natural that air duels featuring fancy maneuvers were treasured by the public. Here was war as it should be. Tales of aerobatic combat became the stuff of journals, including specialist aero journals. To pilots and especially beginning combat pilots, the issue was one of reality, i.e., what portion of the aerobatic duel phenomenon was real, and what portion so much gutter journalism? To Richthofen, as a struggling early air fighter, a correct assessment was crucial.

The highly respected Die Luftflotte saw an important role for fancy aerobatics. In its discussion of air-fighting techniques, it offered the story of a clever looper, acting to simultaneously foil his attackers and win a dominant position, from which to destroy them.1 Here was a complete reversal of roles, owed entirely to a loop. British aero journals offered similar loop-to-victory tales, some featuring precise details of aircraft, time and place; impressive compilations smacking of the truth. To the press, the moral was clear: mastery of the aerobatic arts was the key to air combat success.

Much used by Richthofen, it became his yardstick for measuring British fighter plane capabilities. Note superb upward vision. Source: Flugsport, May 1917, p.338

(translated from original) “The

Tactics of Air Fighting”

Outnumbered and under attack, clever pilot (1) performs a loop ending in new position (2). Once there, he’s safe from enemy fire and well placed for launching his own attack. Source: Die Luftflotte, September 1918, p.194.

Alphonse Pegoud, Master of Stunt Flying

The greatest of pre-war aerobatic pilots, his skills were scorned by Richthofen as useless for air combat. Source: AVIA (Netherlands), June 1915, pp.159.

To Richthofen, this view was disturbing. Comparing himself to the famous French pre-war aerobatic specialist Alphonse Pegoud, he announced for open publication (Spring 1917): “I am not a Pegoud, and I do not wish to be a Pegoud … a flying man may be able to loop and do all the tricks imaginable and yet not succeed in shooting down a single enemy … the aggressive spirit is everything.”3

Detailing his anti-aerobatic views in a confidential internal Air Service study, and singling out those very loops relished by the press, he wrote (also Spring 1917): “Looping the loop is worthless in air fighting. Each loop is a great mistake … a loop only offers a big advantage to the adversary.”4 More generally, he believed: “Many English airmen try to win advantages by flying tricks while engaged in fighting, but as a rule, it is just these reckless and useless stunts that lead them to their deaths.”5

Clearly, Richthofen’s views were strongly held. Certainly, there is no doubt as to his early 1917 position. Right or wrong, they reflected his 1916 experience combined with a mixture of personal bias and sound logic – the usual stew we prepare in order to arrive at a practical position in a too complex world.

For bias, there was his use of famed Pegoud to exemplify all-out aerobatic piloting. One of the earliest of aces (6 victories), French Air Service pilot Pegoud was shot dead by the rear gunner of a two-seater in August 1915. At the time, much was written about his career and the details6 were certainly known to Richthofen. He reacted by treating the air combat death of Pegoud as proof of aerobatic ineffectiveness – no man could hope to be more proficient and yet, what good had it done him? Where was the gain?

The death of Pegoud was unrelated to aerobatics. Instead, he had been caught up in a shooting duel against a two-seater. The tactics employed were of the gun-versus-gun type sometimes used by Richthofen. However, the technical limitations of Pegoud’s aircraft were much more severe. For example, Pegoud’s fighter lacked an interrupter, instead requiring firing through its own propeller disk area – despite inevitable hits on the propeller. Finally, his luck was bad.

According to the Berliner Tageblatt,7 victorious German pilot Walter Kandulski was initially attacked by Pegoud in the usual shoot-from-behind fashion. Return fire was offered by the twoseater’s rear gun. However, after about 30 rounds, the rear gun jammed. The pilot then started a defensive circle, hoping to make Pegoud’s shooting task more difficult. Well understanding the sudden lack of return fire, Pegoud closed in for the kill, only to find that the jam had been cleared by the frantic rear gunner. Pegoud himself, just yards away, had suddenly become an easy target. He was hit by a bullet to the head and killed.

Though certainly a brave man, it wasn’t enough. The combination of bad technology, too close an approach, and terrible luck was too much and he lost out. Despite Richthofen’s statement, aggressive spirit alone was not “everything”. The right tools and tactics were essential, along with much luck.

A pro-aerobatic advocate might argue that Pegoud would have been wiser to employ his noted aerobatic skills to either confuse the two-seater gunner, or to occupy the two-seater’s blind spot, rather than to approach closely in a shooting duel. In other words, the death of Pegoud could well be interpreted as a vote for aerobatics. Far from drawing that conclusion, Richthofen chose the opposite possibility instead.

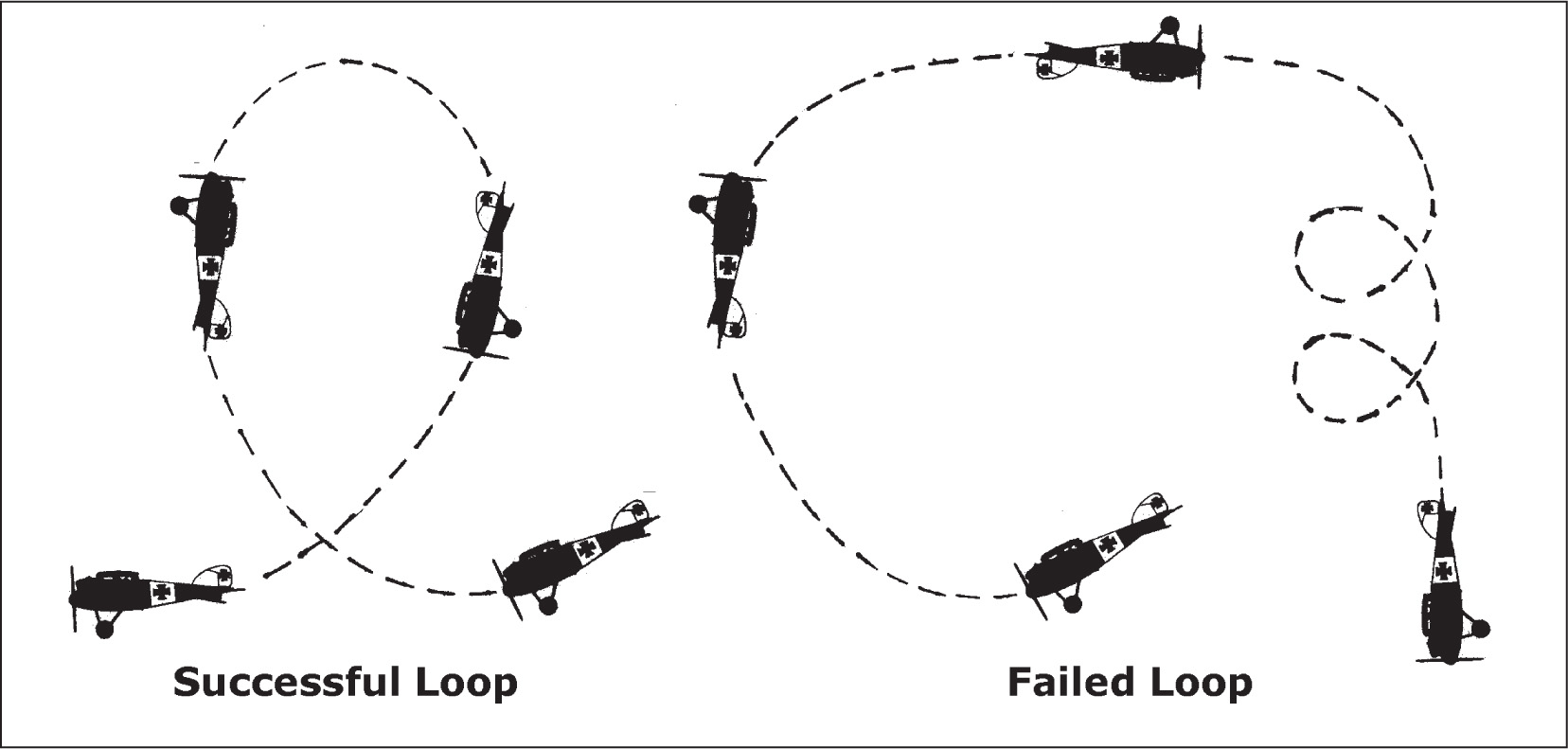

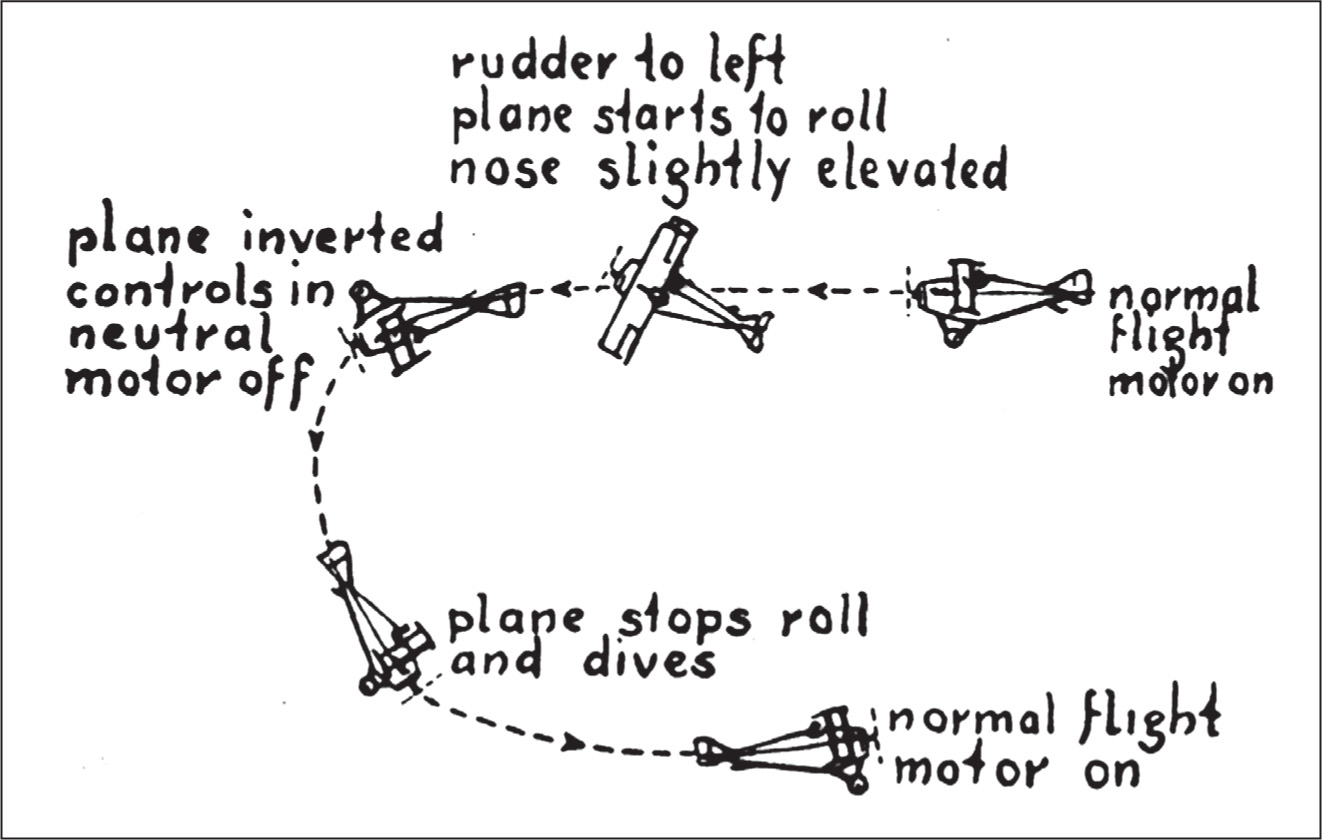

As a part of his justification, Richthofen damned the loop. In truth, there were disturbing factors in looping. The loop sketched below, successfully shifting a fighter plane’s role from that of a target to an aggressor, required an exquisite sense of control stick force application and timing, along with many hours of practice. Even then, a number of things could go wrong.

(left) A well executed loop could result in a winning position behind one’s enemy. However, if poorly done (right), the resulting failed loop meant loss of control, stall and spin. Source: Original sketches by author.

For one, aircraft of the time were incapable of looping from the horizontal start shown, owing to a lack of engine power. Instead, it was necessary to first dive through a considerable change of altitude, building speed. Surrounded by attackers, it was likely that a hopeful looper would be shot down before he acquired enough speed to loop.

Looping was speed sensitive in other ways as well. Once into a loop with too little speed at hand, many aircraft had a tendency to “hang” at the top or upside down position. Breaking out of a failed loop usually involved loss of control, ending in a stall and spin. Should there be enough speed to complete the loop, there was still a question of the loop size and form, largely determined by the instantaneous speed of the wings meeting air in a slightly differently fashion each step of the way as the aircraft went around. Predicting the resulting loop format – ranging from a narrow, or up and down spike to a generous circle – was beyond the abilities of most pilots, even those who were highly experienced.

The loss of speed implicit in the looping maneuver was of itself a strong negative factor to Richthofen. He believed that a fast speed and high altitude were the most important virtues possessed by an aircraft moving towards combat. With superior speed and altitude, he could flee or attack as he chose. Without these, he was merely somebody else’s target, with no say in the matter. Guided by this outlook, even the temporary loss of speed experienced on the up-going side of a loop seemed a threat.

As a final discouragement, with engine power output so heavily dependent upon altitude, knowledge gained from the practicing of loops at one altitude might well be useless should combat take place at a different height. In short, looping as a tactic had many genuine drawbacks.

To Richthofen, the single most important measure of tactic acceptability was reliability. To aid his planning, certainty was wanted. Anything smacking of loss of control was out. Looping, with all its risks and possible nightmare conclusion – finding oneself stalled and upside down in a failed loop – was out of serious consideration.

This most difficult form of loop–the inverted type– was part of Pegoud’s stunt flying exhibitions in pre-war days. Source: Flight, September 27, 1913, p.1066.

Another form of loop – the outside loop – also widely associated with Pegoud was, if anything, assessed as worse. The resulting G loading on man and machine was severe and it was quite possible to sustain personal injury or aircraft damage, even in a well executed outside loop. In short, as Richthofen saw it, advocates were not only wrong, they were dangerous fools.

In addressing the aerobatics issue, he had moved a great distance from his original, open minded, beginner’s stance. The change reflected his own skill, plus lack of certain skills, together with the application of much pointed logic. All was finally tested against two major influences: Boelcke’s teachings, and those of his own combat experience.

Boelcke stood for simplicity and direct action. His 1916 dicta advocated no form of trickery. Instead, he offered only straightforward common sense. The result was a less than perfect fit to reality; in part, because so little was known of air combat at the time. A second limitation was the deliberate avoidance of many awkward aspects of combat. For example, it was all very well to advocate attack from the rear (see dicta # 5) but what of real life tactical situations where only frontal attack was possible? Was a frontal attack merely less than optimum, or truly wrong? If not a winning move, was it a losing move? On this sort of sticky issue, Boelcke had nothing to say. Unhappily, there were many such unmentioned matters.

Richthofen, an appreciative pupil of Boelcke, was determined to carry on his work. Loops were a poor fit to Boelcke’s philosophy of straightforward attack. Furthermore, loops required some loss of eye contact with the enemy: a violation of dicta #4. In short, looping was suspect and unlikely to gain Richthofen’s support, unless it demonstrated some saving merit. What of his own combat experience? True, combat against British two-seaters had produced no enthusiasm for aerobatics, but what about their livelier single-seaters? Wasn’t looping of some use in keeping up with single-seater maneuvers?

October 1916 saw the initial three Richthofen victories over single-seaters – by chance, all BE12’s. He was not impressed with their capabilities. His combat reports8 offered nothing about maneuvers – aerobatics were never an issue. Instead, he noted the considerable altitude at which combat occurred – as much as 10,000 feet – a height suppressing engine power and therefore acting to curtail aerobatics. As in his two-seater combat, the number of rounds fired was in the high hundreds (350, 400, 500) – numbers suggesting not duels, or a struggle for superior position followed by an execution – but a remote and leisurely outpouring of bullets, offered in the belief that given enough time some would strike home.

In effect, he treated the BE12 single-seater as though it was one more sluggish two-seater. If anything, he found the BE12 to be an easier opponent than the usual two-seater, for there was no rear gunner to deal with. As for the anticipated single-seater high maneuverability, no such ability was apparent. Three combats at various altitudes convinced him that high altitude alone wasn’t to blame – something else accounted for the BE12’s lack of liveliness.

The British largely agreed. Read between the lines, the official British BE12 test pilot’s judgement was damning: “This machine, if possible, is almost easier to fly and land as the BE2c … an excellent machine for night flying and Zeppelin chasing.”9

What seems to be praise described a low maneuverability type of aircraft; an easy to fly machine far removed from the twisted, mean spirited, high maneuverability type. The BE12 was simply one more peaceful, highly stable aircraft. Landing slowly and without tricks, it was suited for night flying at a time when airstrip illumination was poor. Despite the lack of a serious aerobatic capability, it was capable of hounding Zeppelins, for those swollen monsters offered even less in the way of stunt flying ability. In short, BE12 maneuverability shortcomings prevented any comparison with the livelier set of contemporary single-seaters, such as the Nieuport Bébé. As a result, all-out aerobatics – loops included – were unnecessary in dealing with the BE12. Richthofen’s assessment and tactics were exactly right.

A “booty” aircraft presents its side-mounted Vickers machine gun, unhappily located too far from the pilot’s cockpit (extreme right). Source: Luftfahrt, March 1917, p.18.

What of friskier machines? What of British hopes for the DH2? Was it truly maneuverable or merely one more hapless fighting aircraft of the too stable, too stately persuasion? Employed to take on Richthofen’s D-II, was it really capable of doing the job or was it just one more over-matched loser?

The DH2 had its good points. In some ways, it was superior to the Albatros D-II. One major virtue was a low gross weight, leading to a light wing loading, with each square foot of DH2 wing area carrying less weight than the D-II’s: specifically, 27% less.10 Given a lighter wing loading, the necessary flight speed required to generate sufficient lift was correspondingly less. The result was a lower minimum flight velocity for the DH2 as compared to the heavier D-II aircraft. The profit was real, for in a circling duel, the winning innermost circle was flown at the slowest speed possible. In short, the DH2’s ability to fly at a lower speed met one of the key requirements for getting to the innermost circle.11

However, there was another crucial need for inner circle flight: great power. Flying slowly in a tight circle at the usual banked attitude produced much drag, which required extra offsetting power. Without enough power, a circling machine would lose altitude and become a tempting target for its more powerful opponent. Altitude could always be converted into speed, and so the more powerful machine’s fully retained altitude permitted a diving attack upon a lower opponent. It was only necessary to leave the pursuit circle and dive on the enemy – a simple procedure.

(top) The German Albatros was superior in terms of power and reliability. (bottom) De Havilland’s machine offered a lower wing loading, leading to better maneuverability. Richthofen strongly preferred his Albatros. Source: Original sketches by author from 3-views in L’Aérophile, June 1917, p.203.

In short, success in a circular duel depended on both one’s wing loading and available power. Of these, the DH2 was superior in wing loading but inferior in power. It carried a French-designed Gnome Monosoupape rotary engine of 100 h.p. output – much lower than the D-II’s 160 h.p. Mercedes – and offered much less reliability in the bargain.

Unfortunately, the low weight of the DH2 rotary – helpful in reducing wing loading – was obtained by accepting a dreadful engine capable of valve failure after a few hours of frontline flying. In contrast, the heavy Mercedes won a reputation for reliability; one known and respected even by the British.

Their profiles hint at the nature of the machines. We see a heavy, streamlined, powerful Albatros D-II tractor, as against a frilly, lightweight DH2 pusher. Neither was ideally suited for all-out aerobatics – the D-II was too heavy and the DH2 too limited by power constraints and diving limits.

Yet, both the D-II and the DH2 made for effective fighters. If unable to shine at stunt flying, each managed to be an able practitioner of pursuit circle dueling – always an important talent. The success of each type supported Richthofen’s growing belief that aerobatics capability of itself was unimportant. Too many other other factors shared the spotlight. There were forced choices to be made between a fast tractor as against a slow pusher offering better visibility; between a single Lewis gun without an obstructing propeller as against multiple Maxims and an interrupter; between the ability to evade through steep diving, as against survival despite serious injury, through no-hands stability. Indeed, the list of painful and uncertain choices was endless. In a world too full of choices, extreme maneuverability and stunt flying seemed merely one more option, and a largely profitless one at that.

Richthofen (right) and fellow officers inspect a captured DH2, searching for weak points useful in future combat. Source: Johannes Werner, Boelcke der Mensch, der Flieger, etc. (Leipzig: Koehler, 1932) p.188.

One problem with Richthofen’s early maneuverability assessment was a lack of personal stunt flying experience, either his own, or that performed by British enemies. However, in the special area of circular duels, Richthofen’s experience was considerable, for his D-II met and fought against the DH2 type, producing victories starting in November, 1916.

To British DH2 pilots anxious to draw maximum power from their feeble engines, the altitude of the duel was critical, for Gnome output fell off badly at a high altitude; certainly more severely than did the competing Mercedes. As a result, the best tactic for the British was to engage on the deck; while for the Germans, it was best to fight only at upper altitudes. If combat started at a medium altitude, the natural tendency for all circular duels to drift downwards – the result of power inadequate to meet desperate pilot demands – produced tactical concerns of its own. At some low altitude, it was best for the D-II to quit, for the bottom 1000 feet belonged to the DH2.

On top of these basic tactics and worries came the special issue of one’s own engine. All pilots sweated the number of flying hours between overhauls. Performance suffered as post overhaul hours accumulated. In the case of the Gnome, too many hours could well mean a dead engine – a final stoppage, delivered without warning.

Seeking victory #11 in November 1916, Richthofen engaged a DH2 at 10,000 feet.12 Entering into a circular duel, he was surprised to find an opponent who was his equal in every respect. Many minutes later,13 circling all the while and down to a low 1600 feet, it was time to think about ending the duel. Other tactical considerations weighed in: they were well behind German lines, with the prevailing wind towards German held territory, and despite an anticipated Gnome power surge at low altitude, the English pilot’s circle showed no sign of improvement. To simply continue the same tight circling down to the ground meant surrender for the British pilot.

Major Lanoe G. Hawker’s hopes for much improved engine performance and resulting victory at a lower altitude had failed – victim of one more lemon Gnome engine. Instead of winning the circling duel as he neared the ground, he found that he could barely hold his own position relative to Richthofen. A change of tactics was necessary. He broke from the circle and tried a diving exit towards the frontlines, about half a mile away.

Richthofen followed, satisfied to shoot too many rounds (his estimate: 900) at a remote and fleeing target, certain that some bullets would hit home. He was correct: though one of Richthofen’s twin guns jammed, Hawker was shot dead.

Learning afterwards that his opponent had been a famous ace, known for aerobatics in the Immelmann style, Richthofen employed Hawker’s death as further support for his ever-stronger anti-aerobatics stance. After all, what had Hawker achieved with his special skills? True, given an aircraft with an inferior engine, he had been able to match Albatros turning ability – an effort requiring great aerobatic skill on Hawker’s part. But to what end? Avoiding lemon engines mattered, not aerobatics.

Richthofen’s next victory (# 12, December 1916)14 was also gained through a circular duel. In this match a less able pilot – again flying a DH2 – lasted for only a short fight at about 9000 feet. Next came (# 13, December 1916)15 a lengthy replay of the Hawker circular duel struggle, also against a DH2 as opponent, but with a different ending. Losing patience, Richthofen crossed the circle’s diameter to open fire a plane length away – defying his own concerns over collision – and succeeded instantly.

With all his 1916 experience pointing in one direction, his assurance concerning the worthlessness of all-out aerobatics was complete. To Richthofen, what counted was the right aircraft – fast and powerful – together with a set of no-nonsense tactics. If the British foolishly pushed the fancier aerobatic skills as crucial, too bad for them.

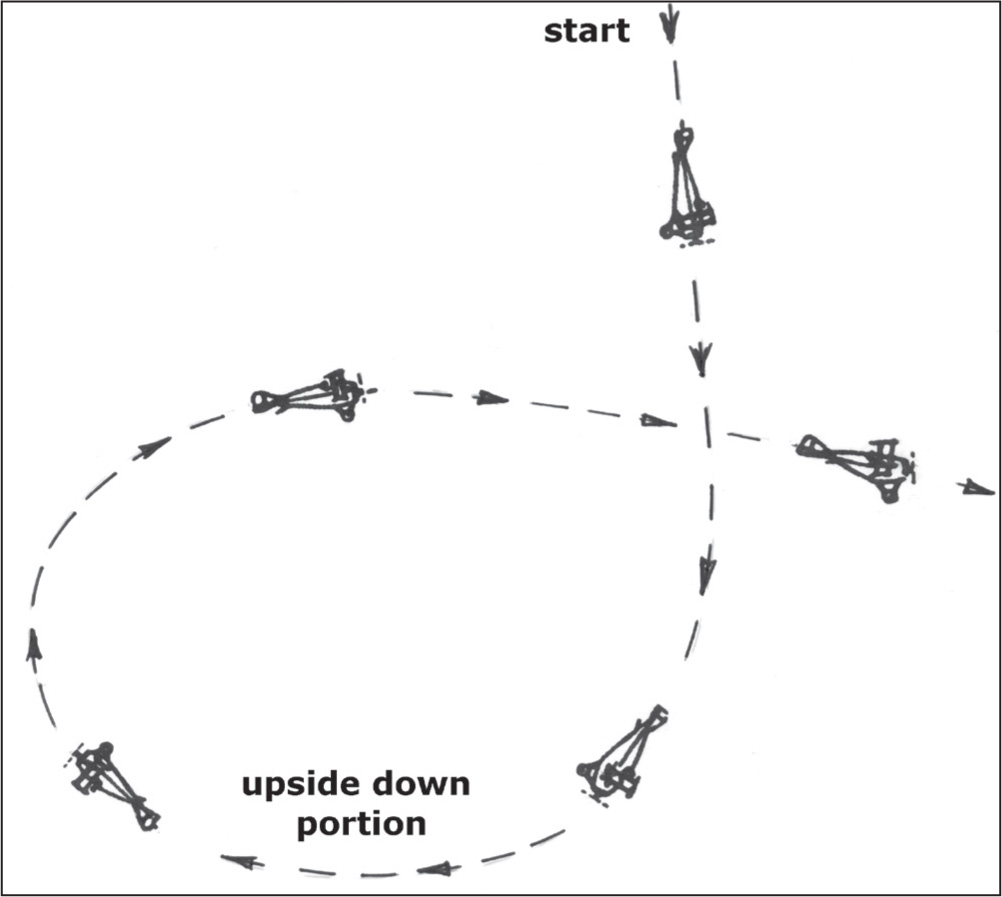

Of course, some elementary stunts and maneuvers were necessary to change position or altitude. At times a full knowledge of maneuvers was required in order to pursue enemies – especially those fools convinced that some tricky maneuver was a sure path to victory. For these practical reasons, Richthofen studied and practiced the more popular maneuvers. Truly profitable was the sideslip.

In its simplest form one flew with a great deal of yaw, produced by rudder offset, automatically losing altitude while continuing to move in the same basic direction. In effect, one was flying slightly sideways, with the resulting high drag causing a drop in altitude. To end the process, the rudder was simply returned to neutral. Every pilot made occasional use of the notion in landing: if coming in too high, a bit of slip corrected matters by cutting altitude. In combat, full-scale sideslip made judgement of one’s flight direction difficult for an enemy, for the resulting aircraft flight path trajectory was at some uncertain angle with the fuselage centerline. As a result, shooting allowance became a matter of guesswork.

A useful maneuver offering a difficult target and a quick loss of altitude. Source: Aerial Age Weekly, November 4, 1918, p.422.

If real, a spin meant a major problem on board; if faked, a trap for those willing to follow. Tricksters delighted in this one. Source: Aerial Age Weekly, November 4, 1918, p.422.

The French version shown was ambitious, simultaneously cutting altitude and changing direction to permit as much as a 90° angular shift of flight path. To a pursuing enemy unfamiliar with the maneuver, confusion was likely and accurate shooting impossible. However, with enough practice all became predictable – and so offered little gain. Richthofen’s response was to work at becoming a knowledgeable, practiced pursuer; one impossible to fool.

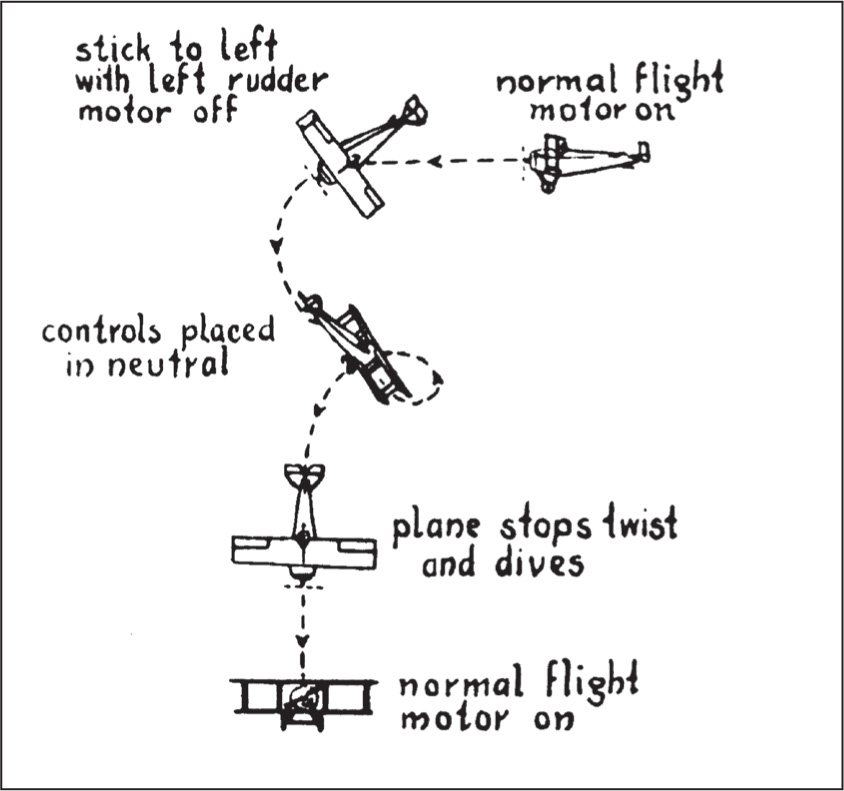

A spin was a more effective way of evasion through loss of altitude, for the spin’s wild spiraling descent offered recovery and gunnery problems to those enemies daring to follow. The likelihood of unwanted spin was real enough to all pilots, with stalled wings first, plus some yaw, leading the way. Even cautiously flown aircraft were vulnerable, sometimes inducing spin as a result of a failed maneuver or a broken flying surface. No aircraft type was exempt: even the docile BE2, if pushed beyond its limits, would spin readily.16

Despite the grim atmosphere surrounding spin, spin in combat was frequently employed as a deception, fooling attackers by pretending serious or even fatal injury. Faked spins were especially useful as a ploy for those on the receiving end of heavy attack, with the spin convincing the attacker that he had succeeded in hitting hard. Should the attacker follow his fast descending victim, he might be caught out by an instantaneous spin recovery at a much lower altitude: fake spins were frequently used as traps.

Real or fake? Never an easy call, the spin’s sense of impending calamity attracted users who saw profit in the wild gyrations. One such was Richthofen’s younger brother and sometimes fellow combat flier, Lothar. Fiercely competitive and well aware of Manfred’s disdain for trickery, Lothar practiced a form of one-upmanship by deliberately using the faked spin in Manfred’s presence.17 Introduced whenever the immediate opposition seemed too skillful, his faked spin was usually followed downwards by an opponent sensing victory and seeking a confirming crash. Instead, upon nearing the ground Lothar would suddenly use his speed and power bonus to get above the surprised enemy; and once there, to blast him.

Manfred was unmoved by Lothar’s success with faked spins. A spin was of itself a worrisome thing, offering an iffy recovery path that was never certain. Another serious drawback was the inability to see one’s opponent steadily, if at all, while spinning. As spinning tactics broke important rules, they were suspect at best.

His brother’s very use was an additional negative vote. Tricks were all very well for Lothar, who lacked the right hunting instincts and therefore twisted air combat into a strange, hardly recognizable game. In Manfred’s considered view, “Lothar was a butcher, not a sportsman.”18

Some slight chance did exist for combat pilots to fight a noble war; a war rather like a series of duels, where one might respect a fallen enemy. To Manfred, this chance was worth pursuing, for otherwise all was mindless destruction of the poison gas or monster cannon type. Trickery could not lead to the desired result. To generate respect, fair play was necessary. As guidance concerning acceptable, if sly practice, best were those hunting rules found honorable over the centuries. For example, there was hunting’s “flushing a covey”, used to excite game birds into flight. In this ploy, shots were fired without aiming, simply to urge the birds to take wing.

His own version of this tactic consisted of opening fire much too early at an out of range enemy; spooking the previously unwary opponent into a fearful retreat, seeking his side of the lines and safety. This form of straight line exit was exactly suited for an attack by Richthofen’s higher performance machine; with the straight line aspect making accurate shooting easy. Soon caught up, his enemy would be readily destroyed. True, a trick of sorts was involved, but it was of the approved hunting type. His contempt was directed at the other kind: aerobatic trickery. Here, practitioners flew striking but pointless maneuvers aimed at deception instead of attending to business: that of attack or defense.

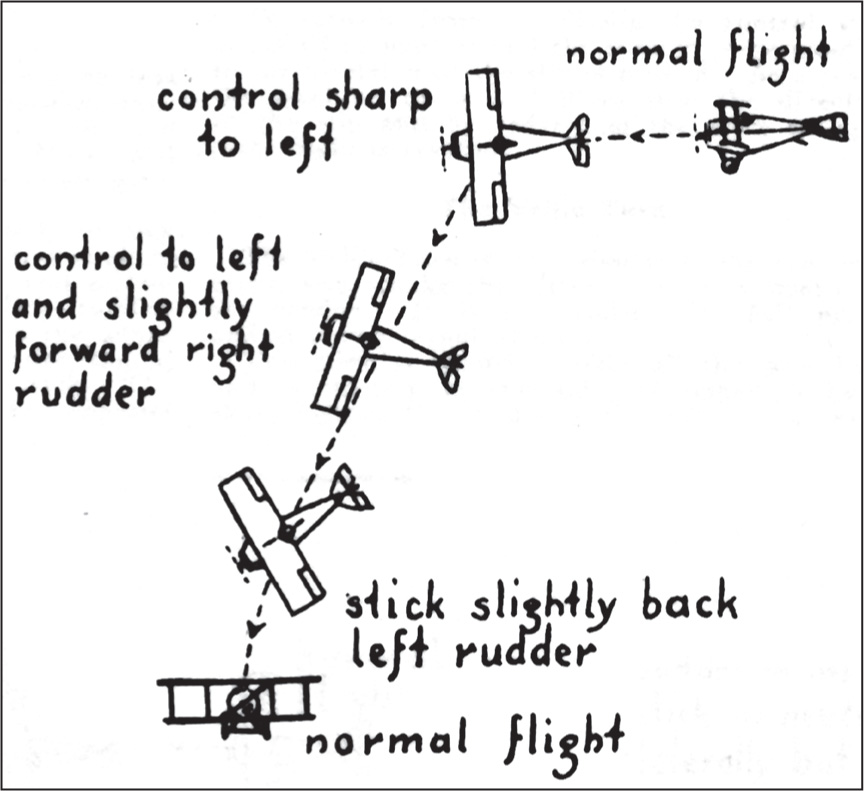

Not all maneuvers made for trickery. A quick turn about was essential for all combat fliers. Both the Immelman turn and the similar French renversement successfully changed flight direction. To French ultras, the Immelmann turn was simply a warmed over copy of their own pre-war renversement. Of the two, the renversement usually resulted in a greater altitude loss. In making a choice, pilots reasoned that superior altitude was essential for most forms of attack, and so for the most part favored the Immelmann. However, those trained in pre-war days sometimes continued with the more familiar renversement.

The standard pre-war means of quickly reversing flight direction. Source: Aerial Age Weekly, November 4, 1918, p.422.

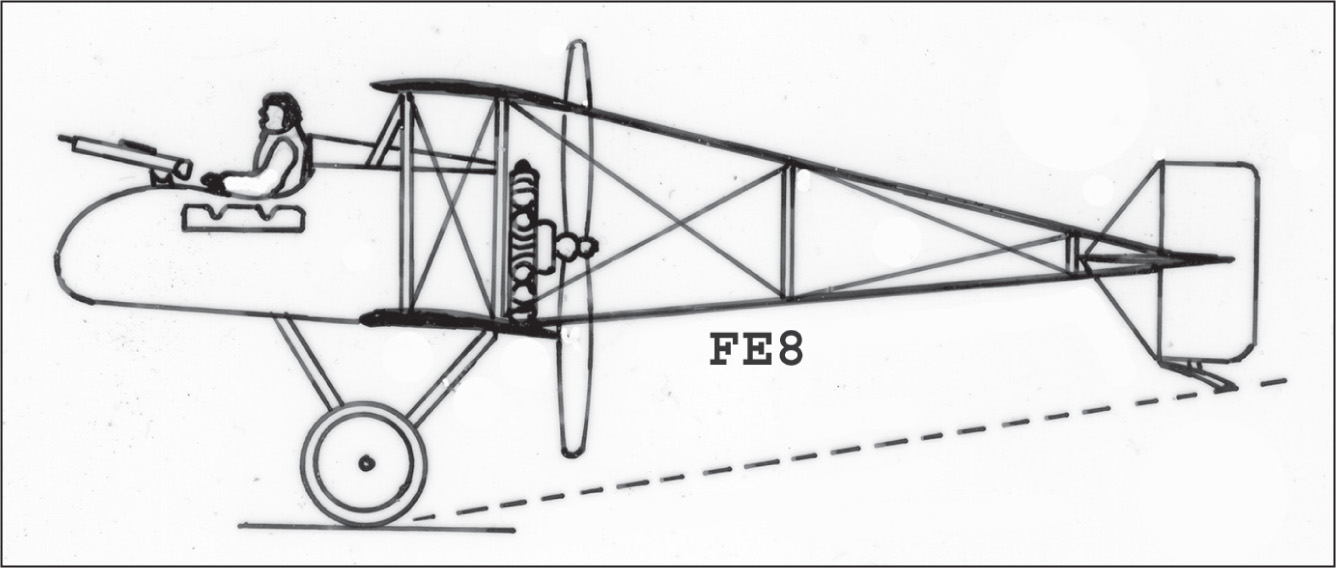

Last of the Pusher Fighters –FE8

One more mediocre aircraft, low in performance and cursed with an unreliable engine, this RFC scout came and went in 1916-1917. Source: Flugsport, July 1917, p.430.

To Richthofen, the Immelmann was superior because attack logic favored it. Yet he found it necessary to master the renversement, for he might find himself in pursuit of one of its practitioners. Indeed, far from fading away, the renversement was attractive to hopeful tricksters because it lent itself to a faked spin. We suspect that the pressure to acquire unwanted aerobatic expertise – largely because some enemy pilots thought well of tricky maneuvers – increased his resentment of both tricksters and aerobatics.

Better than trickery was the right aircraft – a fast one capable of a high climbing rate – but the British seemed incapable of changing their ways. Late in 1916, with the woes of the DH2 known, came the FE8 of similar appearance, presumably offering a revised, up to date fighter capability.

Once again, the pusher concept was followed, powered with the same deficient engine burdening the DH2. Though its all-up weight was a bit less, its top speed was less than 95 mph19 at a time when Richthofen had well over 105 mph20 in hand. Combat showed the FE8 to be but one more hapless fighter plane, offering little challenge to the Albatros D-II.

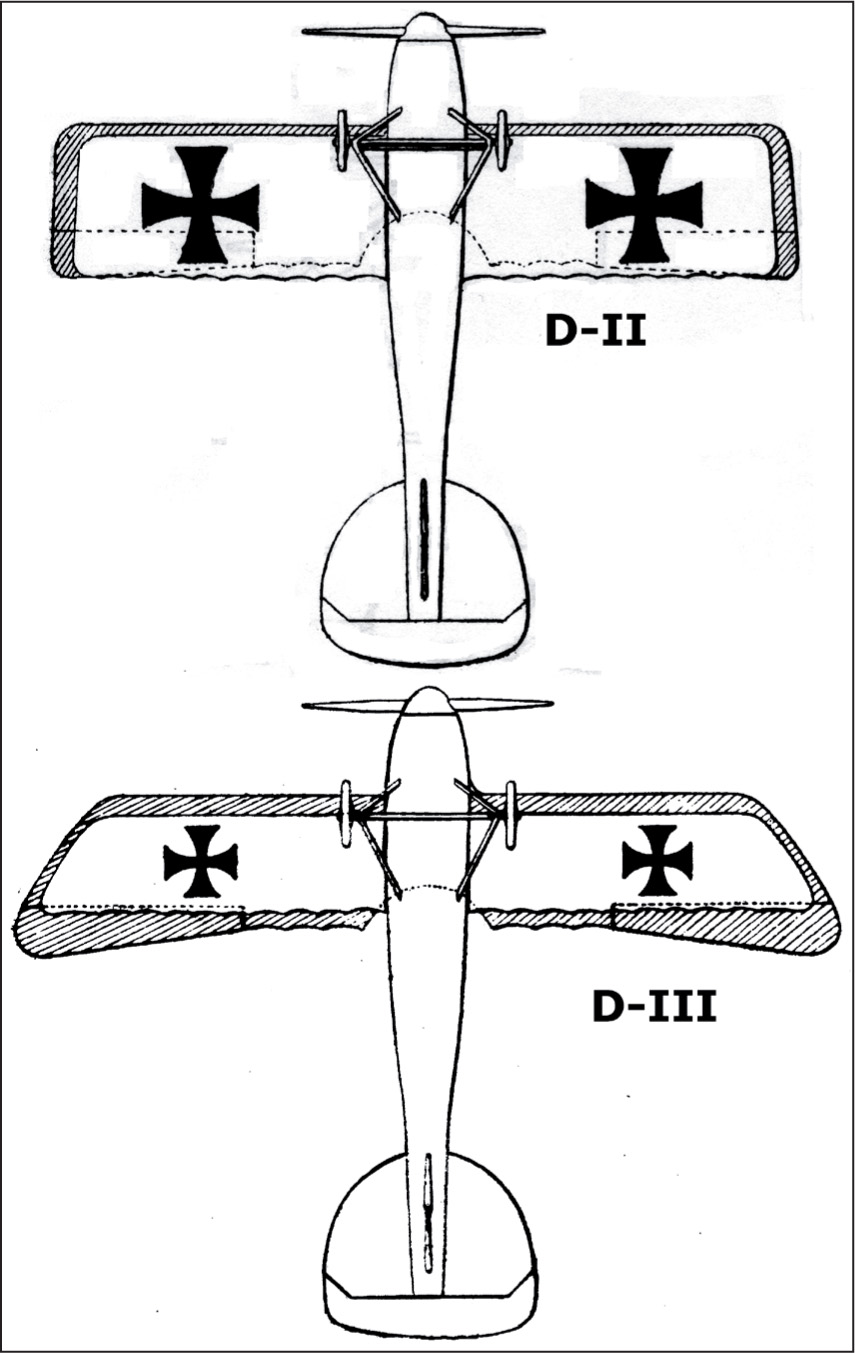

Further increasing the odds against the FE8, Albatros delivered a freshly re- designed and much improved D-III, starting in January 1917. The new machine was in line with Richthofen’s wishes: the twin gun, high-speed features were retained and bolstered with a higher climb rate, all placed within a package offering improved visibility. The key change consisted of new wings, largely “borrowed” from Nieuport design concepts.

Biplane wings disturb one another in flight. Each wing roils the air through which the other passes. It is more efficient to have a single large wing to supply the necessary lift. However, Great War fighter aircraft designers usually found this impossible for reasons of stress and strain, and so the biplane configuration prospered, despite its inefficiency. Some gain could be achieved by placing the wings far apart to reduce the interference. Another helpful approach was to make one wing – the top wing – much larger than its brother, and draw the bulk of the lift from this bigger surface. The smaller wing was retained primarily for structural reasons, its low value of generated lift minimizing the roiling of the air though which the large wing moved. Such was the D-III.

Though its reduced total wing area meant less drag, there was a price involved – wing loading increased, making tight circling that much more difficult. Other design factors were pushed, seeking a compensating gain. Rounded wing tips were introduced, as were “trapezoidal” ailerons. Finally the engine output was boosted.

When all was done, the greater efficiency produced a profit – less drag at any speed. How to best use the profit? There were two possibilities: faster speed or a higher climb rate. We would expect a compromise: some modest improvement in each. Not so. As the old D-II was much faster than opposing British machines, its speed was ruled sufficient and retained rather than improved in the D-III. Instead, the profit was poured into climb by carving the propeller blade angles a bit differently. At low altitude levels,21 the D-III climb rate was upped by 25% as compared to the D-II. Eliminated was the only area of DH2 performance superiority – low altitude climb rate. Compared using the yardstick of performance, both the DH2 and its brother aircraft the FE8 were decidedly inferior to the D-III.

The updated D-III of 1917 was given less wing area, but used it more efficiently. After adding more power, the result was a much higher climb rate. Source: L’Aérophile, June 1917, pp.203-204.:

There were D-III problems: early wing failures when diving steeply, required a lengthy de-bugging process. Once corrected, the D-III represented a striking improvement over the D-II. Despite a large supply of competing German fighter aircraft, it would serve as a first line machine for many months in 1917 – as able as any.

To a considerable extent, Richthofen’s anti-aerobatic stance was made possible by the performance superiority of his D-II and D-III machines as compared to those of his British opponents. With a lead in speed, climb and dive, he could dictate whether and when combat would occur. Against his enemy’s sluggish fighters, simple tactics prevailed; he learned that many victories came from pursuing frightened pilots at a safe distance, simply filling the sky with bullets. Given a machine as capable at circling as any possessed by the enemy, he could win circular duels without concern for stunts. If matters grew unpleasant, he could leave at any time without employing tricks of the faked spin type. Instead, he could exit simply by diving away at high-speed. No enemy was capable of following.

He concluded that straightforward attack or retreat were the only reasonable approaches to combat, for they led to clean success; victory without the sleazier aspects of aerial trickery. Oddly enough, he pointed to the “will to win” as all-important. “The thing is done by the personality or by the fighting determination of the airman.”22

We suspect that this view, implying that the individual counted more than the machine, was based on something taken for granted: the superiority of his fighter airplane to those employed by the enemy. Suppose he had the inferior machine? What then? Would trick flying appear unacceptable if only trick flying permitted him to survive? What price his rejection of sly schemes?

An important change came with the new year. In a fight occurring on January 1917 he “saw immediately that the enemy plane was superior to ours.”23 It was the new Sopwith Pup. For the first time the British possessed a competitive fighter, and a highly maneuverable one at that. Excellent in many ways, the D-II and D-III did not excel in maneuverability aspects. Until the Pup, maneuverability meant little to Richthofen. What of the future?