Tactics and The Right Kind

In the endless search for more victories, tactics were never permitted to become rigid. As aircraft and guns improved, offering more in the way of performance or maneuverability, combat techniques shifted accordingly. The endless changes required a certain free-floating outlook for acceptance and survival. Pilot personality mattered. Determination was necessary; however, rigidity could be fatal.

In turn, pilot temperament exerted considerable influence on tactics. Their usual short life span led to great respect for those few men who managed to survive beyond the usual several months of frontline duty. However, even admirers sensed some of the techniques employed by the best fighter pilots as odd. Did their very oddness mask genius? Was pilot survival a matter of the proper genes, assuring superior intelligence and faster reactions; or had some men quietly mastered superior tactics of their own; tactics better suited to combat than those of the enemy? Finally, was the achievement of a great many victories in aerial combat itself a matter of skill or luck?

Each Air Service struggled with these questions. As background, each strained to keep its pilot supply pipeline full, a severe burden at best, but when facing the huge demands of 1917, an impossible task. The practical result was to speed training along by offering tyro pilots the least instruction possible. In April 1917, by official admission, British pilots were “going overseas with an average of 17 1/2 hours instruction in the air.”1 These were men who could barely fly, much less fight. In the view of General Frederick Sykes,2 many such poorly trained beginners “fell easy prey to experts like Richthofen.”

In similar fashion, starting in the autumn of 1917 German pilot trainees were no longer drawn from those who had previously served as observers or gunners. Instead, recruits with no prior war experience of any kind were trained and sent into combat directly,3 a shift assuring a greater immediate supply, plus larger losses soon to come – losses owed to ignorance.

For those who survived, there came the inevitable question: how was it done?

Was it mostly a matter of background? The right parents?

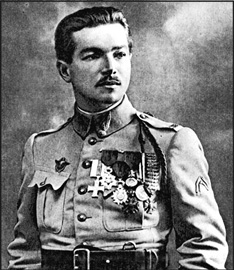

At the highest military levels, the European class system dominated the search for personnel, pressing a belief that the best men came from birth within the right family: one of ancient, land owning nobility, with a long military tradition. As a prime example, there was Captain Baron von Richthofen, solidly maintaining his role as first among Pursuit Wing leaders. To General von Hoeppner, one of Manfred’s key qualities was “a knightly bearing.”4 Unsaid, but implied, was the respect due to a warrior descendent of Prussian warriors, fighting along side his younger brother, Lothar.

Here was a gifted pair reflecting every quality capable of delighting recruiting officers, for they were military school graduates with a strong hunting background, expert horsemen, active rather than reflective, well spoken and physically sturdy – in short, the best sort of professional soldiers, obviously slated for command. So clearly were these “the right kind” as to raise doubts about all other backgrounds and abilities.

Many believed aces such as Oberleutnant Lothar (left) and Rittmeister Manfred (right) owed much to their ancestors and upper class background.Source: (left) Luftfahrt, June 1917, p.15; (right) Deutsche Luftfahrter Zeitung, April 1917, p.12.

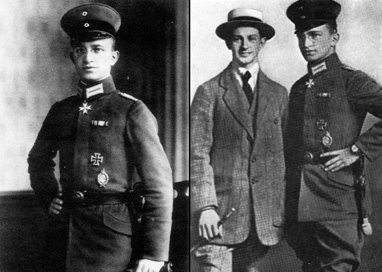

Confusion came with the second highest German scorer, Leutnant Ernst Udet (62 victories). His father5 was a plumbing expert, specializing in installation of the newly popular coal-fired hot water bathtubs. Though an honorable task, its lack of nobility was all too evident. Furthermore, his father despised Ernst for failing in those qualities considered manly. Instead of sports, or better yet, hunting as a hobby, young Ernst was content to build and fly model airplanes, or to draw, for his ambition was to become an artist – an ambition bitterly opposed by his father.

To some extent, Ernst was pushed into a passive role by his small size. He never reached the 5 feet 3 inch height (160 cm.) officially required to become a German airman.6 His physique was correspondingly slight. Inadequate at conventional sports, he sat out school play periods, his time spent in drawing.

With the war, and quick rejection as a volunteer soldier, came flying lessons paid by his father, pleased to see Ernst do something other than draw. Once a licensed pilot, the Air Service proved unable to resist the bargain that he represented – that of a volunteer pilot trained at someone else’s expense – and so, height be damned, Udet was in. Assigned to a quiet sector, he acquired the necessary skills on his own; learning the shooting and aerobatic arts necessary to survive while slowly accumulating victories.

Of command capabilities, he had none. Instead, he was a “lost generation” character, determined to make life a non-stop party, with each partygoer a personal friend and every short woman within reach considerably more than a friend. His wish to become an artist matured into a caricaturist’s wicked skill. After the war, he survived and even thrived as a light aircraft manufacturer, but slowly wearied of a life spent as an alcoholic (Champagne) womanizer. Coming off the highs was difficult and there were periods of black depression. Nonetheless, a splendid reputation as an exhibition pilot and designer brought him a position as a top ranking Luftwaffe General, concerned primarily with warplane design. However, working directly under the thumb of a thoroughly hated Hermann Goering was one burden too many. In a final fit of despair, Udet ended his life with a pistol shot7 in late 1941. He was 45.

Totally unlike Manfred in either background or personality, playboy Udet became the second-ranking German ace by war’s end. Source: Flugsport, July 1918, p.331

A gifted cartoonist, Udet made fun of those prominent in the aeronautical world, starting with himself. Source: Ernst Udet, Hals und Beinbruch (Berlin: Wilhelm Kolf, 1928) p.104 (left) and p.79 (right). Cartoon captions have been translated and updated by author.

Surely few aces were more unlike the Richthofen brothers. Lacking in officer qualities, he was suited for few 1914-1918 roles other than the one he filled, that of a fighter pilot. Yet, like Manfred, he was undeniably one of the greatest of fighter pilots. His personal input was not of the revolutionary type. Instead, joining the Richthofen Squadron after his 19th victory, he made the best use of those tactical improvements already in place, following pioneering efforts by Boelcke or Manfred. These included emphasis upon combat itself, rather than the flying of patrols. In practice, this meant endless moving of the squadron to catch the tide of battle, plus five flights per day instead of the usual three. New fighter designs tended to come to his famous unit first, and he had the advantage of early introduction to the Fokker Triplane, followed by the later Fokker D.VII biplane.

His single greatest strength was that of flexibility – of not pushing any tactic to extremes. Aerobatics, always his strong suit even when flying the relatively immobile Albatros, was useful up to a point, as were gunnery skills. The trick was in recognizing the limit; of pressing hard when advantageous, and fleeing combat when not. His classic single-handed aerobatic struggle with French ace Guynemer8 summed up Udet’s ability: though he lost the encounter, he survived to fight another day. Given enough luck, skill and common sense, one could do well indeed.

What then of knightly qualities? Were those considerations of family background and athletic skill used in flying officer recruitment all wrong? Did a too short pilot hold some advantage over a similar opponent of standard height? Were there other aces of the too short or too tall variety? Were those men requiring eye-glasses really hopeless as fighter pilots?

To examine the effect of personal input on fighter pilot performance, it is useful to have a standard defining “superior”, and we shall use the twenty victory level as a guide, limiting our choice of subjects, with some exceptions, to pilots achieving between 20 and 80 victories. Nations whose pilot scores were considered include Austria-Hungary, Belgium, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Russia and the USA.

Those men chosen for detailed examination – roughly a dozen – reflect the limited sources of available personal data, drawn largely from articles or books written after the war by survivors and professional writers. Unfortunately, those who were shy or poorly educated tended to avoid this process. As for the dead, they were sometimes honored with highly distorted tales. Thus our sample may well be biased. Despite this inherent limitation, it can be said that every man considered below was a highly successful fighter pilot, serving in either the German, British, French or American Air Service.

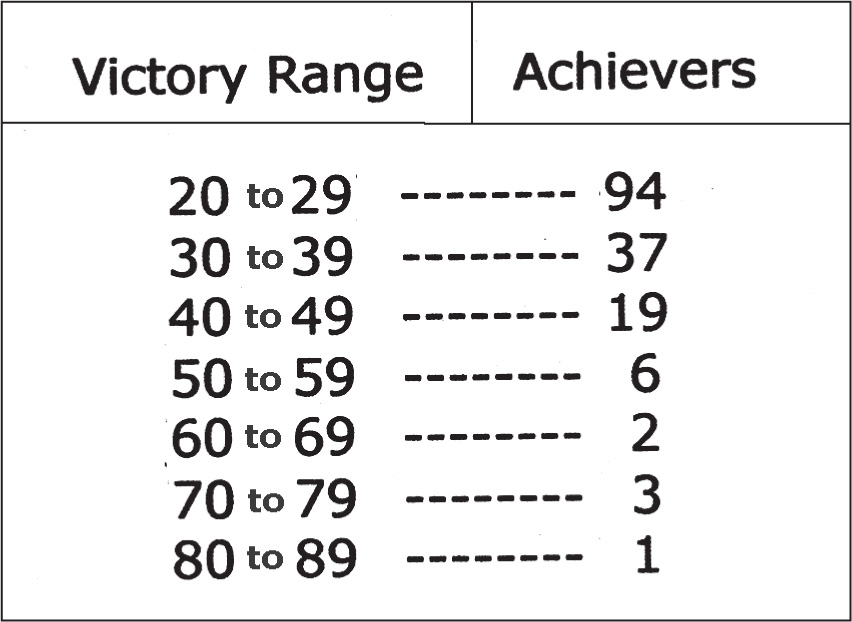

The totals below reflect the difficulty of accumulating more than the usual run of several victories, a difficulty that increased with every victory gained. For example, some 94 men were able to reach the 20 to 29 victory level, but a grand total of only 4 men were able to reach the two highest categories, that of 70 to 80 and 80 to 90. Manfred and his kind were truly rare individuals.

The number of men achieving top aerial victory scores in the 1914-1918 war. Source: Assembled by author from data, Ezra Bowen, Knights of the Air (Alexandria, VA: Time-Life, 1980) Appendix p.196

Aside from Udet, what were these great achievers like? There was another short, slight, and most successful warrior: Captain Albert Ball (44 victories); height – 5 feet 6 inches. A very different sort, his personality was quite unlike that of Udet, for he was a dour loner. His fellow 60 Squadron member Lieutenant Stanley Vincent described Ball as “a quiet introspective little chap … living in a solitary state in a small hut with his violin … we called him ‘The Lonely Testicle.’”9

Rejecting companions and crowds, Ball preferred to fight alone, despite the seeming advantages of wingmen and formations. Source: Frank A. Mumby, The Great World War, Volume 7 (London: Gresham, 1918) p.136

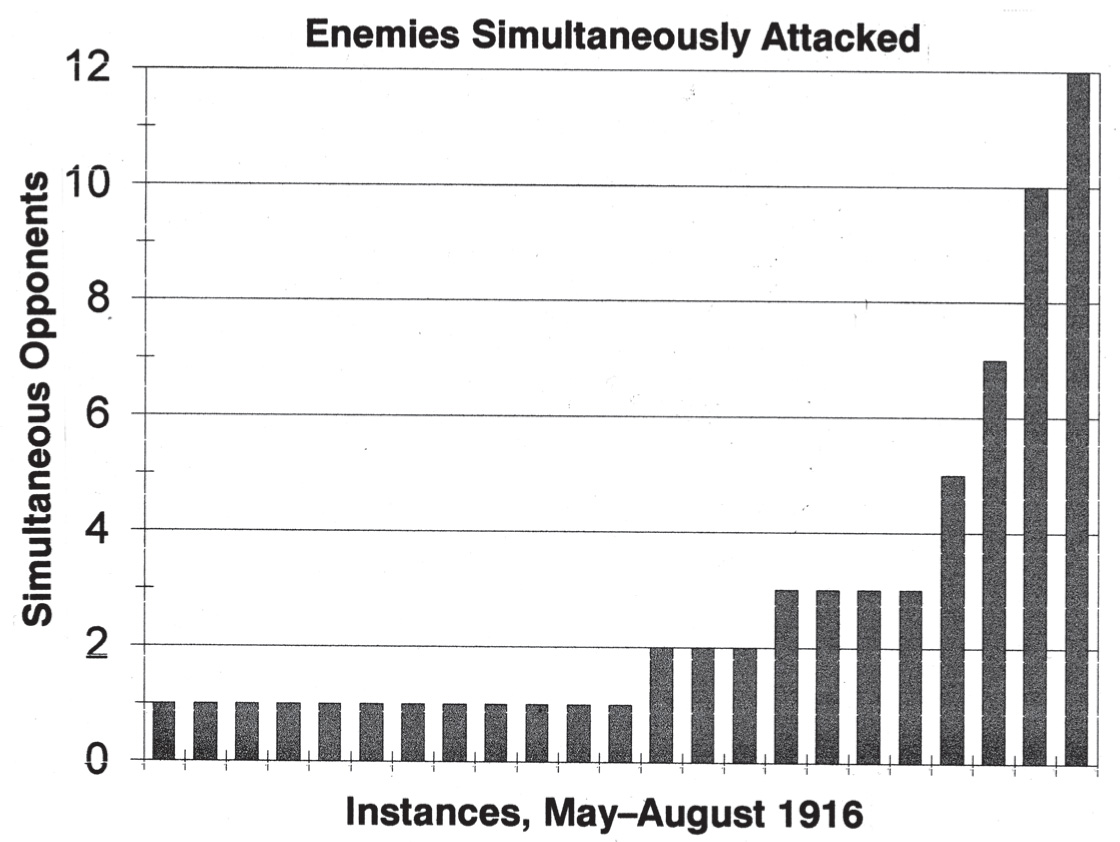

Loner Ball successfully tackled many opponents simultaneously, in numbers ranging from one to a dozen. His success raised the question: why formations? Source: Author-assembled chart from data in A.J.L. Scott, Sixty Squadron, RAF (London: Heinemann, 1920) p.16.

His withdrawn personality was confirmed by Lieutenant William Fry. “Not sociable … he would escape to his hut as soon as he could.”10

Ball was markedly different from his own father, who moved socially upwards from the role of local plumber to become Mayor of Nottingham. Young Ball reacted by turning away from people and politics, instead busying himself with practical engineering of the DIY type. His ultimate peacetime ambition was to become an electrical engineer.11

Aside from his own impressive combat record, Ball made three distinct contributions to combat tactics. First, he preferred to fly and fight alone. His victory count alone stood as sufficient justification for a concept unpopular with high command, proving that a lone hand pilot, disdaining wingmen and formations alike, was capable of succeeding in a big way. His success suggested – as an awkward truth – that teamwork was largely pointless, for gifted individuals were the true rulers of the skies.

Secondly, the number of enemy aircraft he chose to engage simultaneously exceeded all norms, for Ball was willing to plunge into massive enemy formations. True, he did not employ this startling tactic frequently, and most of his fights were of a more conventional sort. See chart above.

Ball never rejected the prospect of dealing with only one enemy at a time and a dozen such one-on-one encounters were tabulated for the mid-1916 period shown. However, he was quite willing to accept unequal combat, should it present itself. Three fights against a pair of machines were recorded, as were four fights against a trio of opponents. Still larger numbers were tackled, and as many as a dozen enemy machines were fought simultaneously.

Schoolyard wisdom suggests that it’s easier for five boys to gang up on one, than for one boy to gang up on five. Coming at a time when strategic thinkers saw overwhelming numbers as the path to victory, Ball’s approach was truly unusual. Why did he persist? On his side were the well known problems of formations: fear of collision, inability to signal one’s fellow pilots quickly, inability to handle novel situations and a tendency to fill formation slots with the newest, rawest pilots available. Bursting into the middle of an enemy formation, Ball’s unstable Nieuport 17 was well suited for the catch-as-catch-can fight that followed – one that favored the lithe and skillful at the expense of the sluggish and unskilled. As for the many guns against him, enemy pilots were reluctant to shoot, for fear of hitting their own men, while loner Ball could shoot freely at anything in the air without concern. These factors permitted Ball to invert the odds. In short, he learned that finding oneself outnumbered by fearful, nervous enemies in sluggish machines could be a good thing.

A third Ball contribution was the extensive use of a pull-down gun to shoot upwards. Unlike the first two Ball ideas, this notion attracted support and followers. Use of this concept in the SE5a followed, with wide appreciation of the tactical advantage offered: that of attacking an enemy from a lower altitude. It was especially suited for attack on two-seaters, with the aggressor first locating himself in their usual blind spot, behind and below the tail.

So long as he flew the Nieuport 17, Ball wasn’t handicapped by the limitations of his size or strength. Pushed into accepting the SE5a, he complained, not of lack of strength, but of lack of maneuverability. As compared to the Nieuport, the SE5a’s greater stability meant inferior maneuverability. However, strong pilots could offset the machine’s reluctance to change course by forcing the controls, through use of brute force.12 Competing German pilots did exactly that throughout the lengthy series of Albatros fighters. Forced to do so, Ball complied reluctantly. There was something to be said for muscular pilots.

We know little of Ball’s death. Whether he was downed by an enemy or a storm cloud remains unclear.13 As with Richthofen, he paid the price of loners: going to his death with much uncertainty as to the means. Instead, there was acclaim from General Trenchard, and an admission by knowledgeable editor C.G. Grey that of all fighter pilot’s deaths, that of Ball’s “had a gravely depressing effect.”14 That so skilled and daring a fighter could not survive was disturbing. One needed more – what?

Major Edward “Mick” Mannock (61 to 73 victories) stood 6 feet tall and presented an impressive military figure. An Army brat, his father was a mean drunk who deserted his young family after slyly pocketing all available funds. In short, the man was a monster. In time, Mannock’s openly expressed hatred for his father was converted into an anti-authority stance, favoring Anarchism.

To earn his bread, he dropped out of school at age 13 and became a manual worker, somehow managing to play ball (cricket, rugby) and study history while working a full-time schedule. Caught and interned in Turkey by the war, he was sent home (April 1915) where he enlisted, transferred to RFC flight training (late 1916) and achieved a back-handed appreciation from his instructor, “I always thought he was the type to do or die.”16 Nothing was said about skill.

Introduced to combat, he freely offered advice to old hands from the depths of his ignorance. Laughed at, and forced to face reality, he began schooling himself on the fine points of shooting and aerobatics. Success as a fighter pilot came slowly and respect even more slowly. He was too excitable17 to fit the nerveless image viewed as properly heroic. When off duty, he joined drunken parties featuring indoor rugby with its pileups and injuries, to be followed by keening sessions where he wept for the dead.

In time, his success as a fighter pilot became obvious, though it was marked by excess. To wear a huge false beard while on patrol was Mannock’s unique combination of rebellion along with dedication to duty. To machine gun an enemy aircraft already downed was pointless, yet it permitted him to express rage in an acceptable form. To fire warning shots at one of his own Squadron members sensed as cowardly was Mannock’s own special solution to the problem of fear. No matter what his behavior, his Squadron members merely shrugged. Mannock seemed but a barely contained explosion.

Top ace Mannock was admired for his efforts to help beginners. Though subject to emotional spells suggesting nervous breakdowns, he fought on. Source: Ira Jones, Tiger Squadron, (London: White Lion, 1954) p.144.

Deflection Shooting: Mannock’s Formula

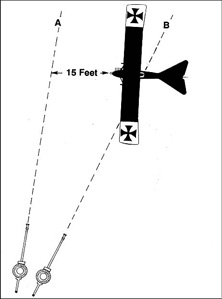

For a right angle hit, he advised hosing the enemy, starting well ahead of the nose (A) and moving rearwards to (B) before a final reversal, moving back to (A). Source: Sketch by author from data in Ira Jones, Tiger Squadron (London: W.H. Allen, 1954) p.102, 124

Yet, there was a saving grace: he cared about, and actively helped beginners. At a time of withdrawn, loner aces, he put himself forward as a teacher, never losing sight of the tyro’s agony. He taught not only with words, but with unforgettable deeds. The combination was most unusual.

Mannock possessed the gift of gab. His audience was thirsty for combat know-how. His particular strength was for simple solutions to complex questions; solutions that were neat and easily retained. Unfortunately, oversimplification was inevitable in such forced solutions, and omissions were common.

Consider the experience of Captain Ira Jones (40 victories). This short pilot (5 feet 5 inches) failed to score a single victory in his initial 16 combat encounters. For the most part, he saw and fired at enemy machines crossing his own trajectory; in other words, his targets moved at right angles to his bullets. He sought Mannock’s advice. How does one hit a target moving at right angles to one’s own path?

He was advised18 to sight about 15 feet ahead of the enemy’s engine before opening fire. Shooting steadily, he was then to shift the aiming point rearwards towards the pilot, before finally pushing the line of fire forward again. Mannock reasoned that by continuously shifting the stream of fire, it would be on target at some point, even if only for an instant, and so a few bullets were certain to strike home.

Though the concept appeared sensible, too much was left out. Four independent factors matter greatly in aiming, of which the factor considered – lead or deflection – is but one. Also entering into the proper direction of fire are assessment of enemy range, speed and attitude. At best Mannock’s hosing process might have offered a few bullets with the right deflection, but was incapable of compensating for serious errors of the speed, range or attitude type.

When Jones tested the advice, it didn’t work, much to his surprise. Yet his admiration for Mannock remained strong. Even if sometimes mistaken, Mannock shared his knowledge. To the truly desperate, even oversimplified solutions to the problems of combat seemed better than nothing.

One of Mannock’s popular maxims had to do with choosing the altitude best suited for attacking an enemy machine: “Always above; seldom on the same level; never underneath.”19

Again, a partial truth is apparent. A higher altitude did have merit. As one virtue, altitude could always be traded for speed. Thus, the top dog in a dogfight was assured a reserve of speed, if needed. Secondly, employment of a diving pass, starting from a superior altitude, had the special virtue of being safer than most aggressive tactical moves. If all went wrong, for example, should a suddenly jammed machine gun ruin one’s chances, the dive could be extended as necessary; if need be, all the way home.

That said, Mannock’s call for superior altitude ignored the considerable success gained by those attacking from below. For example, most of Ball’s victories were obtained with a pull-down gun used against targets moving at a superior altitude. Even conventionally mounted, horizontal guns were successfully used by attackers zooming from below, after initially hiding in the target machine’s blind spot – below and behind.

In short, “never underneath” managed to ignore many worthwhile, proven exceptions. Yet, Mannock’s maxim was highly successful, for it offered a bit of easily recalled advice; a triumph of the pithy and memorable over the messiness of reality.

Mannock himself came to an uncertain end. He was likely brought down (July 1918) by anti-aircraft fire, as the result of breaking one of his own rules; that forbidding flight close to the ground, in pursuit of an “out of control” victim. The irony of his own death reminds us that despite flaws and omissions, each of his maxims contained more than a grain of tactical truth.

If neither Udet’s 5 feet 2 inches height or Mannock’s 6 feet were obstacles to a career as a fighter pilot, was there a limiting line to be drawn anywhere? Consider one of the tallest of British aces, Lieutenant Cecil Lewis, at 6 feet 4 inches.

Though his 8 victories were low as measured by our 20 and up standard, they were certainly significant. His solid background as both a fighter pilot (SE5a) and test pilot testify to practical piloting ability. Aside from his recruiting officer’s plaintive: “I don’t think you can get into a machine”,20 no real problem resulted from his excess height. As for the doubtful recruiter, he was converted by Lewis’s description of his most proper upper class background; one strong on athletics. To either the RFC or the German Air Service, physique mattered somewhat, but other desirables – class and money – mattered more.

Lewis was another loner of the Ball type. He believed that one’s personal outlook was crucial and sought “steely courage, drained of all emotion.”21 His later career as a scientific test pilot did call for a thoughtful approach and the same outlook may well have seen him through combat.

However, in the matter of combat, many types of outlook succeeded, so long as they were matched to the abilities, tools and tactics of the individual. Ball’s contempt for the odds against him worked well – for Ball. Mannock’s rules worked well – for Mannock. Others attempting to copy their success had little luck, for they lacked something in the way of skill or personality.

An especially striking difference in personality and approach was demonstrated by France’s two leading aces. One national hero stood for open attack and stoicism, the other for cunning and forethought.

French Captain Georges Marie Ludovic Jules Guynemer22 (53 victories) had the overlong name of those with a great many honored ancestors. His father graduated from the French equivalent of West Point and spent his life as a professional Army officer. However, from birth it was obvious that young Guynemer was not of the same stripe, for he was a sickly child without the good health and endurance necessary to achieve more than a minimal education. Though of average height, his slope-shouldered, broad-hipped body was not that of an athlete. Competitive sports were set aside and he turned to non-competitive exercise, such as roller-skating, for physical activity.

With the coming of war, and after repeated rejection by medical boards, he was finally accepted as an apprentice aircraft mechanic. Like Udet, he proceded to make use of an open back door. Using family connections, he swung admission to an Army flying school and graduated, to become a two-seater (Morane) non-commissioned pilot. The downing of a snooping Aviatik launched his career as an aerial fighter. Demonstrating a strange fatalism, he attacked without concern for tactics or odds. The result was a mixture of victories and losses, for he drew many bullets, rarely finishing a fight without a few bullet holes on his machine. He appreciated the maneuverability of the Nieuport series, but moved on to enjoy the greater power of the SPAD.

Captain Georges M.L.J. Guynemer

(translated) “French Nieuport Biplane with machine gun fastened to top wing.” Source: Flugsport, May 1916, p.267.

The French public came to identify with him. Something about his frankly admitted defeats suggested honesty. Taken together with his frequent illnesses, rumored to stem from tuberculosis,23 his resulting image differed from the usual Superman offering, to become that of Everyman, succeeding through sheer guts.

As for tactics, he stated24 that there were but two useful for fighter attack. The first was his own or “mad” [dog] approach, whereas the competing method, used by most pilots, featured aerobatic maneuvering. In attack, his goal was to press for the classic position a bit behind and below the enemy machine, and once there, “cling to him like a leech … shooting in jerks [bursts]”25

Unfortunately, his approach was too direct and his goal only too obvious; the very lack of subtlety serving to greatly increase his risk. In his words: “Those who were rarely hit were better at maneuvering than myself … I never have recourse to aerobatics.”26 Here was another of the Ball school – to hell with cunning – just go for the enemy.

What about the drawbacks? These were obvious, for he was brought down seven times. Yet, he persisted. As he saw it, hunting must be done according to the temperament of the hunter, and his tactics, flawed or not, suited him perfectly. They were not to be changed.

He vanished in September 1917. When last seen, he was attacking a two-seater from above, challenging the rear gunner with a simplistic, you-or-me form of duel.27 Though his tactics suited him, and led to an outstanding number of victories, the gods of war demanded more in the way of sophistication.

No believer in luck, France’s most successful fighter pilot bet his life on a striking ability to anticipate enemy maneuvers. Source: La Guerre Aérienne, January 1918, p.123.

Captain René Fonck (75 victories) wasn’t surprised to learn of Guynemer’s end. Questioned about rival Guynemer’s tactics, Fonck said: “Guynemer fought differently. He faced fire regularly. This strategy is very dangerous. It places the pilot at the mercy of a jammed gun. I always utilize blind spots … ”28

The criticism was fair. Guynemer’s willingness to engage in open duels came with a built-in unhappy ending, for in the long run probability ruled: some day the enemy must win the duel.

Fonck’s scenario was attuned to skill, not luck; his goal one of getting into an enemy’s blind spot and staying there. He would outfly the enemy. We sense an innovator, a man who treasured logic above all. Yet the man himself, far from generating respect, was rated low by his fellow pilots. Here was one more complex, conflicted individual.

Called up at the war’s start and assigned to the Engineers, Fonck found himself depressed by the endless labor of bridge building, relieved at times with calisthenics. He transferred out, training as a non-commissioned pilot. His license won, he served as a chauffeur to an officer/observer. Bored again, he sought the role of a fighter pilot. To test this possibility, he mounted a fixed machine gun aboard his twin-engined Caudron GIV; a gun that only he controlled. Though painfully slow and clumsy, Fonck’s machine was a good match for older enemy reconnaissance machines. The lash-up’s first victory (July 1916) sent his superiors a clear message of ambition. They responded wisely, transferring him to a single-seater Squadron flying SPAD VIIs. He was on his way.

Unlike Guynemer, he survived to see the war’s end. As for victories, knowledgeable historians believe his true score to far exceed the official number.29 Yet, despite his clear success, Fonck ruled that victory alone wasn’t enough. He insisted upon victory with the fewest possible number of rounds fired, and furthermore, victory without effective counterfire: no enemy bullet was to touch his aircraft. Should this last condition seem unrealistic, it has been reported30 that “in several hundred combats he received only a single bullet in his fuselage.” This alone was a striking achievement.

Despite his accomplishments, he was disliked by his fellow pilots. More than envy was involved. Unlike Mannock, he hid his gift, offering simplistic nonsense as the key to his success. As he told it, his basic secret was “the most complete disdain for danger.”31 Not so. If anything, his secret was one of carefully avoiding dangerous enemy bullets through brilliant flying.

Then there was his formula for combat effectiveness: “regular hours of sleep.”32 To his hard drinking, carousing comrades, Fonck seemed a bragging prig, playing the part of hero. When dislike threatened to undermine group effectiveness, he moved out of officer quarters to live alone in a separate building housing the Squadron restaurant. Nobody complained.

Early in WWII, after France’s defeat, he was employed as an official within the air bureaucracy. Following the war, there were charges of collaboration with the Germans. This stigma, on top of the dislike shown by his 1914-1918 comrades, has made it difficult to place him fairly within the fighter pilot ranks. Though likely the single most successful of all Great War fighter pilots, he is seldom noted today. Lost to us forever is the means behind his uncanny ability to anticipate enemy maneuvers.

Whatever his quirks, Fonck represented forethought developed to a fine art. He was able to sense what his enemy would do next, and so place himself at the optimum position from which to open fire. This ability reflected an extraordinary skill.

Captain James B. McCudden (57 victories) was a British believer in forethought. In many ways equal to Fonck as a schemer, and likely superior as a stalker, he brought a level of patience to the task that was truly unusual. McCudden was another military brat, contending with a Sergeant-Major as a father and a formidable older brother as well. Brother William was the taller, livelier, and more athletic of the two. James was a small, shy lad “ … inclined to be tearful and moody.”33

Inducted into the Army at age 15 to serve as a boy bugler, he proved a misfit. Interested in mechanics and motorcycles, he transferred to the RFC as an engine mechanic; swinging a berth as a non-commissioned gunner/observer, he was chosen for pilot training, worked as an instructor, and finally found success as a lone hand fighter pilot.

Enemy observation aircraft became his favorite target. His approach was that of a patient bird watcher, analyzing bits of knowledge and constructing a structure of tactics that defined the game. Small but crucial questions fascinated McCudden; for example, how would the wariness of two-seater gunners alter as a mission droned on? When were they truly on guard, constituting a menace? At what airspeed were they so blown about by the wind as to be unable to shoot accurately? Exactly how did two-seater climb and descent rates change as time passed over the course of a mission? When was the best time to attack?

His answers were assembled into a practical how-to article on stalking techniques. For example, to eliminate return fire,34 the best move was to open fire with a short burst, without concern for accuracy. The object was simply to frighten the enemy into diving. Once committed, the resulting airspeed of over 130 mph produced enormous wind pressure on the standing gunner, making it impossible for him to shoot accurately. So long as the dive continued, the attacker had a free hand.

Concentrating on the downing of two-seaters, McCudden either originated or tested many tactics, helping move an uncertain art into solid practice. Source: F.A. Mumby, The Great World War Volume 7 (London: Gresham, 1918) p.139.

His advice was correct and well tested – unlike the sweeping maxims of Mannock. Instead, McCudden wrote narrowly, sticking to the facts, with drawbacks listed. Here was a careful man, and a most successful one. Effective both as a loner and Squadron Leader, he served as a hard-working ace. On two occasions35 he destroyed a total of four two-seaters, all on the same day. Of these, the last group of four was downed within a total elapsed time of 1½ hours. McCudden not only developed fresh tactics, but served as his own testing means, then spreading the word by lecturing widely within the RFC.

With fame came envy and all the problems of real life. His lower class “ranker” background wasn’t helpful, for he lived in an officer’s society ruled by class concepts. Unappreciated was his occasional condemnation of RFC mechanics for shoddy workmanship, the result of his own bitter experience as both a pilot and mechanic. In the end, even his detailed compilations of successful tactics were put down as too specialized.36

McCudden died (July 1918) in a takeoff accident of the stall and spin type, a pointless death usually limited to beginners. That so careful and expert a flier could die in so ignorant a fashion seems hard to believe. However, an eyewitness report37 permits no other conclusion. After takeoff, he “ … suddenly put on speed again and rose upward to avoid collision with the tall trees … the machine now appeared to be out of control … ” Once again, too high a rate of climb led to stall, and stall to spin. The final lack of control made a crash inevitable, with the pilot’s death as the most likely result.

A high scoring ace and winner of the Victoria Cross, he served in both World Wars, despite doubts concerning certain of his victory claims. Source: National Film Board of Canada.

In a manner suggesting Boelcke, McCudden undertook the roles of tactics researcher, ace, Squadron Leader and teacher. As did Boelcke, he achieved much, only to die in an accident. The similarity itself suggests that the same roles and types of men existed in each Air Service. However, some men were truly unique. One was “Billy” Bishop.

Major William Avery Bishop (72 victories)38 was the son of a county official living within a small town in Ontario, Canada. As a mediocre student, but good horseman and rifle shot, he accepted conventional wisdom suggesting a military career as his best chance. However, the Royal Military College found him disappointing on moral grounds, accusing cadet Bishop of lying to authority and cheating on a critical exam39 (crib sheets). He escaped ejection only by enlisting at the war’s start.

Short, slight and accident prone, Bishop moved from an assignment as cavalryman to observer and finally to pilot training. Ham-fisted, his twenty hours of air time were unequal to the demands of a Nieuport 17. As though to make his lack of readiness clear, he crashed in a landing soon after arriving at his frontline unit. Witnessing the crash, an angry General J. Higgens slated Bishop for a return to flight school. Fate intervened, and a fresh start was managed when Bishop won his most important victory of them all – his first.

Holding the unenviable position of tail-end Charlie, Bishop responded to the jumping of his Squadron Leader Major Jack Scott by clobbering the aggressor Albatros. Raw beginner Bishop’s victory undoubtedly had much to do with luck, but his bravery and shooting ability were real and evident to all.

Scott was grateful. Scratching Bishop’s reassignment to flight school, he became a great supporter, serving as witness for many of his victory claims and vouching for the reality of numerous combat incidents. Unhappily, study of German sources during and after the war has been unable to authenticate many of the claimed victories.

Of all ace claims, none has been subject to more intense examination than those of Bishop, with the searchers seeking corroboration of victories more convincing than mere statements made by his friends. The resulting Bishop dossier contains much controversial material, including at least one damning work40 and one of spirited defense.41

Lacking a clear resolution, we note the view of American cowboy Captain Fred Libby (14 victories) who was also there, serving in the same 60th Squadron. His report: “We have one pilot [Bishop] who writes a wicked [claims] report. God Almighty! Excuse me while I vomit … ”42

One suspects that Bishop was prone to exaggerate his claims. That said, there is no doubt about his bravery, skill and influence upon tactics. For starters, there was the issue of time aloft. At the time, two missions per day, each of 1½ hours duration were considered plenty. Yet he would frequently fly a total of 7½ hours,43 seeking not only combat, but extra practice. Never a “natural” pilot, he found endless practice a good substitute for having been shortchanged in skill. His implication: the major factor in joining “the right kind” was simple determination, rather than natural ability.

His very lack of aerobatic ability led to increased stress upon gunnery as the path to victory. Wanted in combat was a fast pass and out, as compared to an aerobatic duel – one he might well lose. However, a fast pass meant that few bullets could be fired, and much practice was spent in improving accuracy. Even given the extra drill, his slow but maneuverable Nieuport, usually armed with only a single Lewis gun in a pull-down arrangement, was far from ideal. To Bishop, the follow-on SE5a seemed an important improvement; his explanation: “It’s 40 mph faster and has two guns.”44 Though the SE5a paid a price, giving up a considerable amount of maneuverability, Bishop didn’t care: “This is positively the best machine in the world.”45 His determined support, coupled to a striking combat record, made a sturdy case for non-aerobatic tactics. In 1918’s world of British combat tactics, consisting of the aerobatic as offered by the Camel, versus the non-aerobatic championed by the SE5a, Bishop’s position was clear and persuasive. Fast pass tactics owed much to Bishop.

That Ball and Bishop should have disagreed strongly on the issue of the best machine (Nieuport 17 versus SE5a) is not surprising. Their choices reflected personal combat styles that were far different. Yet, on one secondary issue there was agreement: goggles were not to be worn. They reasoned that whatever was gained in protection from rain and flying oil droplets was lost to the usual smeared vision offered by goggles. A tendency to exaggerate the sense of murky fog experienced inside clouds was another goggle drawback. Bishop especially, convinced that shooting ability was the single most important skill any pilot brought to combat,46 would tolerate no general reduction of vision. As for the flying debris encountered when lacking goggles, one might hope for a momentary blindness of only a second or two before full restoration of sight.

With peace, Bishop became a Canadian businessman, pioneering in air transport efforts. He rejoined the RAF in WWII to serve as a recruiting icon and glad-hander. After the war, he found it difficult to fill a satisfying role. Bishop died of illness, age 62.

(left) Blue Max winner Fliegerleutnant Kurt Wintgens with spectacles, worn at all times. Tony Fokker (right) congratulates Wintgens on his achievement. Source: (left) E.H. Baer, Ed. Der Völkerkrieg Band 14 (Stuttgart: Hoffmann, 1917) p.224. (right) Flugsport, October 1916, p.562.

With goggles condemned by Ball and Bishop, what hopes were there for those who required eye-glasses? Not only were eye-glasses subject to the same smeared vision problems, but their very need pointed to a serious physical defect. Breakage or loss in combat was obviously unacceptable. No Air Service welcomed men who were wearers.

Despite everything, eye-glass wearer Leutnant Kurt Wintgens (18 victories) of the German Air Service played an important development role as a fighter pilot, earning a Blue Max for his services. One more military brat,47 Wintgens initially served in a communications battalion (telegraphy). As an officer, and the son of an officer, he was able to arrange an observer’s slot and then pilot training. Making use of a strong gift for engineering development, he met with Tony Fokker and joined a program to test the new Fokker M5 monoplane. Possessing the key new fighter feature: a synchronized machine gun firing through the propeller disk, the package of gun plus aircraft would shortly change air combat forever. As a test pilot, he was among the first to succeed, downing a French Morane in July 1915. Fame made it unnecessary to hide his eye-glasses and many subsequent photos show him as a proud wearer.

Can one conclude that eye-glass need was not a significant drawback? Not really. They had significant disadvantages, but then all men have blind spots and disadvantages, be it slow learning, lack of strength, lack of feeling for machine logic, excess bravery or fear, lack of a sense of direction, color blindness, too young or old an age, etc. To this lengthy list, eye-glasses must be added. They were not a fatal handicap – just one more problem. In a world of mostly perfect recruits, rejection based upon eye-glass need would be logical. However, in the real world of the 1914-1918 war, the flat rejection of all eye-glass wearing pilot candidates was unwise.

Captain Edward V. Rickenbacker

When photographed he was an ambitious Lieutenant, hoping to command his unit, the 94th or ‘Hat-in-the-Ring’ Squadron. Source: Air Service Journal, July 25, 1918, p.118.

What of education? Every Air Service insisted upon a secondary school education and diploma. Were they really important? Consider the experience of a well-known American ace: Eddie Rickenbacker.

Captain Edward V. Rickenbacker (26 victories), the leading U.S. ace, became the male head of his family at age 13 upon the death of his foreman father. Those surviving included a widow and seven children. Desperate for money, Edward dropped out of school and lied about his age, working the night shift in a series of Midwest factories. Learning that he had mechanical talent: “ … engines have always talked to me”,48 he entered the world of machine tools and practical engineering.

Automobile racing had special appeal and starting as a mechanic, he became a world-class racing driver by his mid-twenties. Entry of the U.S. into the war led to the position of Engineering Officer at the American flight school in France. He would have preferred a flying job, but over-age at 27 and lacking even a high school education, there seemed no chance, until he found racing fans among the admissions officers. Excited by the presence of the truly famous Rickenbacker, his enthusiasts proved willing to ignore the rules and he was accepted for flight training. After collecting twenty five hours of solo flight in primary flight school, mostly in Nieuports, in addition to some meager gunnery training, he became a pursuit pilot assigned to the 94th Squadron, France.

Lithe, tall and athletic (6 feet 2 inches; 165 pounds) Rickenbacker was at his best in a SPAD 13. Tall, strong men had a natural preference for the roomier SPAD, choosing it over the more maneuverable Nieuports. However, more than room and personal strength was involved. A full comparison must credit the greater strength of the SPAD or SE5a, as measured against the weak-winged Nieuports. Preference alone was a good guide to user tactics; with those who opted for delicate maneuvering pressing for a Nieuport, while those who wanted a slashing dive and climb type of attack pushed for the more powerful, stronger SPAD 13.

Of the two, SE5a and SPAD 13, the latter was the stronger. Upon pulling an SE5a out of a dive with excessive “vim”,49 McCudden observed wing tip failure just outside the strut supports. The SPAD had no dive pull-out limitation. Furthermore, in the right hands, the SPAD was the more maneuverable, as demonstrated in a classic mock duel between Lewis and Guynemer.50 High speed was another of the SPAD’s features. As Rickenbacker noted, “No Fokker [D.VII] can overtake a good SPAD unless … by diving.”51 As for the quality of his SPAD, Rickenbacker’s expert knowledge of engines assured superior maintenance or better, on an every day basis.

With man, machine and tactics all in line, Rickenbacker was headed for success, requiring only judgement and luck. However, his judgement was not that of a steady guide: in part it did consist of cool evaluation, but furious emotion also had a role. An underlying drive to achieve peak combat performance and prestige may well have powered many of his decisions, made in the hope of finding a public regard equivalent to his pre-war auto racing position. Inevitably, some of his views seem odd.

On attacking observation balloons, he was a conservative. Daylight attack was too dangerous.52 The necessary low altitude, only a few hundred feet, led to easy hits by defending anti-aircraft guns, with the result that too many attackers were lost in the process. Only attack under conditions of poor visibility – at dawn or dusk – was warranted. This very reasonable decision was countered by his own actions. Pestered by a machine gun nest while crossing over the frontlines, when at a low altitude under good visibility, he immediately swung into the attack mode, strafing the gunners.53 His attack succeeded, but one must question tactics that frown upon the strafing of observation balloons at times of good visibility, for fear of losses, while permitting the strafing of bothersome machine gun nests. Surely destroying an observation balloon was the more important objective, for it might lead to many saved infantry lives, while destroying a machine gun nest would change nothing. On the face of it, his priorities sometimes reflected anger, instead of logic.

Similarly, there was the matter of capturing a crippled Fokker D.VII biplane.54 Caught up in a routine two aircraft dogfight, Rickenbacker managed to hit his opponent’s engine. The D.VII’s propeller windmilled, reflecting the loss of all engine power. Grasping the situation, Rickenbacker decided to take his opponent prisoner, rather than shoot him down. For one thing, the German aircraft bore the red paint insignia of the Richthofen Squadron. Perhaps the pilot was a famous ace, whose capture would add prestige to that of Rickenbacker and that of his Squadron 94. While guiding the acquiescent, gliding Fokker D.VII to his side of the lines and home airfield, Rickenbacker was infuriated to see another SPAD suddenly emerge from nowhere and open fire on the Fokker – “his” Fokker. Rickenbacker’s reaction consisted of firing a short burst at the “malignant SPAD” to warn him away. Despite Rickenbacker’s angry response, the intruder had given the Fokker a final blow: it crashed. The pilot survived, to become a prisoner.

Again, Rickenbacker’s priorities seem oddly mixed. What really mattered was ending the threat offered by the German machine and pilot. With this done, Rickenbacker’s ability to turn the war into a contest for prestige was striking; his anger and action against the competing SPAD were curious indeed.

There was the matter of spare time and victories. Confirmation required trips to the front, seeking witnesses. Ideal eyewitnesses consisted of officers, equipped with binoculars and serving as anti-aircraft observers. The task of locating the proper witness and collecting signatures was one he pursued energetically, for he didn’t wish to have his victories questioned, either then or later. In this he was successful: his victories stand.

However, there was an issue of available time, for each such trip might easily consume most of a day. When taken together with his insistence upon spending more time in the air than any pilot serving under him, there was difficulty in finding that time necessary for handling executive business. His solution was to appoint others as substitute managers. As a result, he claimed55 never to have “spent more than 30 minutes a day” on administrative matters. The curtailment of administrative hours, as compared to time spent seeking victory confirmation, spelled out Rickenbacker’s priorities: first came his victory count, with administrative needs dead last.

Rickenbacker did test and then push for many positive tactical procedures. He stressed the importance of small formations, especially as a means of introducing beginners to combat, and frequently led such formations. His belief in maximum frontline flying hours for himself as Squadron Commander, rather than few, set a demanding standard at a time when few existed. Having decided that only dawn attacks on balloons were worthwhile, he proved his point by organizing and leading such an attack, officially destroying 10 balloons. A strong believer in lone hand fighting, much of his success reflected the wiliness of a solo hunter enjoying the superior machine. Despite his need for prestige, he never put down the crucial importance of the machine.

Not only were positive tactics pursued, but he was willing to label and abandon broken or nonsensical techniques, even those he originated. For example, there was his early (March 1918) ethical resolve: “I will never shoot at a Hun who is at a disadvantage.”56 In reality, his very task as a fighter pilot was to place enemies at a disadvantage and then shoot them down. With the rare exception of the gliding Fokker noted above, he did so without regret.

Rickenbacker’s major contribution to tactics was not that of some single, novel ploy. Instead, it consisted of evaluation of well-known tactics encountered over the Western Front in 1918. His determination to personally test, and rule on all possibilities, made Rickenbacker a powerful judge. Though certain biases were evident, so was a generally high level of personal experience and common sense.

He was that rarest of military leaders, one gifted with an instinctive feeling for the new engine-driven technology. That, and a certain sly shrewdness, yielded tactical judgements of a high order.

With tactics and air victory itself dependent upon the skills and personalities of the right kind – i.e., those with a gift for air combat – spotting talent early in the process became important. Surely efficiency would improve if only prospective aces were given flight training. Could these be recognized? Were there early signs?

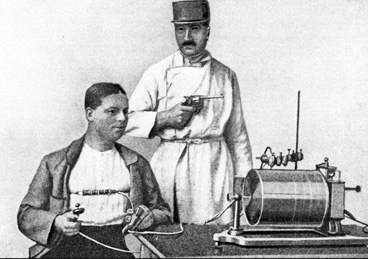

The French tested for coolness in danger.57 Wired as in a lie detector test with devices measuring blood flow and nervous activity, the subject was surprised with a pistol shot (blank) fired at close range, behind his back. The extent of startled response and time required for recovery were monitored. Considered ideal was a phlegmatic response. Those displaying an intense physical reaction were considered unsuitable candidates for flight training.

Cool types, with little reaction to shock, were believed to make good fighter pilots by the French. To find men with a phlegmatic response, reaction to the firing of a pistol was recorded on the cylinder at right. Source: Luftfahrt, December 1917, p.23.

The concept appears based on fictional heroes of the strong, silent type. Seeking men of this sort, respect and points were offered for a sluggish response to menace. In reality, top aces performed well despite nervousness, as demonstrated by Guynemer and Mannock. To the unimpressed British, “the French test was on the wrong tack.” As pointed out by RFC Lieutenant-General David Henderson: “They might get someone constituted like an ox, but this was the very last type to produce a good pilot.”58 Yes, temperament was important, but much more than nervous response was involved. The difficulty was one of nailing down the important aspects, while ignoring the trivia.

A sense of the difficulty is supplied by Mannock’s personal history. Always eccentric, he entered a period in 1918 suggesting a nervous breakdown. His sympathetic biographer59 describes him as “a quivering wreck … saliva and tears were running down his face; he couldn’t stop … ” Yet he fought on, and effectively at that. Separating out those truly impaired by emotional problems was not simple.

Testing some 250 mixed subjects – some successful as fighting pilots, some failures – the RAF drew a composite picture of the candidate most likely to succeed.60

He was an “enthusiastic youngster … knowing little or nothing of the details of his machine … the less the fighting scout pilot knows about his machine from the mechanical point of view, the better … ”

In reality, Udet frequently performed his own engine maintenance and would become a prestigious aircraft designer and manufacturer after the war. Rickenbacker and McCudden were engine experts, more knowledgeable than most RFC mechanics, with each capable of performing a full overhaul at any time. Fonck and Guynemer worked with SPAD engineers to fit a cannon into a SPAD 12, helping solve a development problem requiring much technical input from the aces. A fighter aircraft design by Ball seemed sufficiently promising to result in production by Austin. Finally, despite rejection of the triplane concept by German aerodynamicists, Richthofen succeeded in pushing for a three-winged fighter – a most successful machine – one that was ultimately made by Fokker’s factory.61

In short, the British study resulted in conclusions that failed to meet the test of reality. Our conjecture is that the truth concerning pilot mechanical interests and skills was exactly opposite to the 1918 British conclusion. As for other practical results; for example, the value of hunting or athletics, conclusions stemming from the study are similarly unconvincing.

The temperament of men successful in the air fighting area, one of violent hunting combined with aerobatics and advanced technology, was unknown. Exactly what made for judgement of the correct lead used in shooting? The right answer might be three aircraft lengths or none, with all to be decided in a split second, with possible fatal consequences if mistaken. Adverse conditions – lack of oxygen, gun jams, an oil splattered windscreen – were all part of the picture. Not surprisingly, few were competent. Those truly gifted – the right kind – possessed an ability amounting to genius, and as with music, art or baseball, players possessing genius defy analysis.

Choosing the proper tactics required more than solid thinking. Only afterwards, when laid out for all to see, could one appreciate a daring, brilliant move. For lone hand Ball to break into a large formation, turning its key advantage of many guns into a disadvantage owing to enemy gunners fearful of hitting their own machines, required a certain brilliance. Many of the right kind exhibited this brilliance.

This chapter is concerned with the relationship between tactics and the right kind of men – those successful as fighter pilots. Ploys, schemes and personality traits have been considered. For the most part, tactics came to reflect the special abilities of available fighting machines, after a certain sifting to assure a good fit with pilot outlook and personality. Thus, a fast diving machine would lend itself to a diving attack as a key tactic, and a tight circling machine would most likely be pushed into a dogfighting role.

In the special world of air combat, machine design and logic mattered greatly but men and their special natures mattered as much, and perhaps more.

Tactics stood on three legs: those of design, military logic and temperament.