Hiking up Mount Townsend

Introduction

Olympic National Park encompasses the glacier-clad spires that crown the peninsula as well as the wild and windswept beaches of the Pacific coast. It shelters a rare temperate rain forest ecosystem found only in a few pockets elsewhere in the world. The Olympic Mountains have been isolated from other ranges for millennia, and this isolation has led to the development of a unique alpine community of plants and animals. Some of these are found nowhere else on Earth. This bountiful ecosystem provides a refuge where weary city dwellers can seek inspiration in the midst of nature’s majesty.

The uniqueness of this area was recognized in the late 1800s, when the region was set aside as a forest reserve. President Theodore Roosevelt created a national monument within the reserve in 1909, in part to protect the forest subspecies of elk that now bears his family name. National park status came in 1937, and the additional protection of wilderness status for the remote parts of the park was conferred in 1984. At the same time, five adjoining blocks of national forest land were declared wilderness, protecting 91,000 additional acres of this diverse and beautiful ecosystem. The park and its surroundings have been internationally recognized as a biosphere reserve and a world heritage site.

An extensive network of trails provides access into the most remote corners of the mountains, and a well-planned series of wilderness routes allows hikers to take in most of the Olympic coastline. There are 581 miles of maintained trails within the national park, and hundreds more on the adjoining national forest lands. This book covers all of the maintained trails and designated routes within the park and the adjacent wilderness areas. These trails provide a full spectrum of recreation opportunities, from short strolls to extended journeys that penetrate to the heart of the mountains.

Hiking up Mount Townsend

The Making of the Mountains

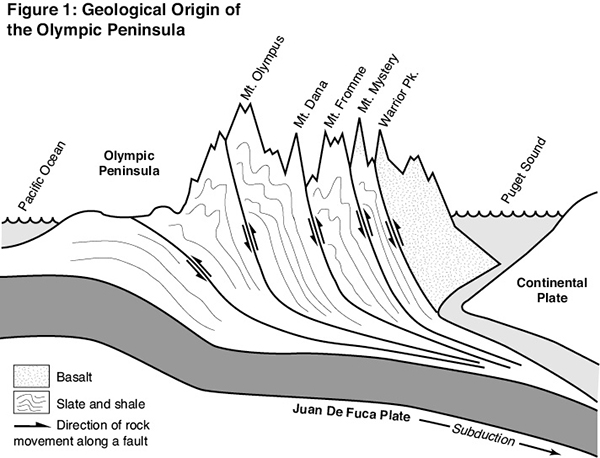

The Olympic Peninsula appears to be attached to the northwest corner of the continent as an afterthought. In geological terms, this impression is absolutely correct. The peninsula is actually the eastern end of the Juan de Fuca Plate, a small terrane that collided with the much larger continental plate millions of years ago. The resulting folding and faulting of the earth’s crust produced the mountains we see today.

These mountains had their genesis on the bottom of the ocean. Cracks in the sea floor allowed molten magma to well up into the water, forming a deep-sea range of volcanoes. These seamounts were already quite old when the Juan de Fuca Plate approached the rim of North America. As the plates collided, enormous pressures pushed the seamounts upward. The Juan de Fuca Plate began to dive underneath the margin of the continent, but the seamounts were wedged against the continental plate, and movement ground to a halt. Beds of sedimentary and metamorphic rock piled up behind the seamounts like boxcars behind a derailed steam engine, with deep faults between them (see Figure 1). The ancient undersea lava beds now form a horseshoe of crags that stretches from Lake Crescent through Mount Constance and The Brothers and extends southwest as far as Lake Quinault. This “pillow basalt” is resistant to erosion, and as a result many of the highest peaks in the range occur within this narrow belt. The interior ranges are a mix of sandstone, shale, and slate. The border between these two formations is a zone of heavy faulting where hot springs well up through the earth’s crust.

The newly created mound of high country was soon dissected by streams, which carved a system of shallow valleys in a radial pattern. With the coming of the ice ages, these valleys filled with glaciers, which deepened them into the U-shaped clefts that we see today. At the same time, an enormous Cordilleran ice sheet filled the Puget Sound basin and lapped against the base of the Olympics like a great frozen sea. It dammed up the waterways, forming huge glacial lakes that extended far into the mountains. Lake Crescent and Lake Cushman are remnants of these glacial lakes, and granite erratics brought in by the ice sheet can be found in certain parts of the peninsula.

The glacial ice receded in recent times, leaving remnants of the great valley glaciers stranded high on the flanks of the tallest peaks. These glaciers still gouge away at the rock, surging and retreating with annual changes in snowfall and temperature. Flowing water is now the dominant sculptor of the landscape, fueled by the heavy rains and snows for which the area is known. Raging rivers have carved deep canyons in the valley floors once planed flat by glaciers. The result is a series of elevated, well-drained terraces that rise high above the courses of most major rivers.

Biogeography of an Island Range

Because the Olympic Mountains have long been isolated from other alpine areas by a sea of lowland forest, their flora and fauna have many characteristics of an island assemblage. During the ice ages, the entire peninsula was sheathed in ice, with the exception of three refuge areas. One was a strip along the coastline, while the other two were nunataks, high mountaintops surrounded by ice. These two mountaintop refugia were located above the Gray Wolf–Dungeness basin in the northeast and in the Moonlight Dome area near the southern end of the mountains. All three refugia must have had an environment similar to Arctic tundra, surrounded as they were by vast fields of ice.

The plants and animals that could live in such an extreme environment survived, while other species went extinct. Some have been able to repopulate the Olympics from the distant Cascade Range, but species that cannot disperse across lowland basins were never able to return to suitable habitats on the peninsula. Notably absent in historical times were the mountain goat, grizzly bear, pika, red fox, and golden-mantled ground squirrel. Many of the alpine plants were able to survive here as Miocene and Pliocene relicts in pocket populations; their nearest relatives now exist in the eastern Rocky Mountains, where glaciation did not wipe the slate clean.

These millennia of isolation have resulted in genetic drift, and new species have arisen here that are unique to the Olympic Peninsula. The Olympic aster, Flett’s violet, and Piper’s bellflower are among the best-known endemic wildflowers; it is instructive to note that each is an inhabitant of alpine tundra. Among mammals, the Olympic marmot, Olympic snow mole, and Olympic yellow-pine chipmunk have evolved coloration patterns and behaviors that mark them as distinct from their closest relatives. There are also the Beardslee and Crescenti trout, a number of beetles and butterflies, a salamander, and even several species of slugs that are found only on the Olympic Peninsula.

The interference of modern man has also left its mark upon the ecosystem. Roosevelt elk were driven to the brink of extinction by overhunting in the late 1800s, and predator control efforts led to the eradication of the timber wolf by the mid-1920s. The loss of wolves and the resulting expansion of coyotes into the Olympic peninsula may be the reason that the Olympic marmot is currently declining toward possible extinction. Mountain goats were introduced to these mountains at about the same time, and had in recent years begun to overpopulate their range. In the interest of preserving native plant species, the National Park Service embarked on a program to relocate the goats to the Cascades. Many of them were successfully removed before the program was terminated, although several hundred still remain.

Original Inhabitants

The Olympic peninsula has been a site of human habitation since Pleistocene times. The earliest record comes from the vicinity of Sequim, where mammoth remains showing evidence of butchering were dated at 12,000 years before the present. During the intervening centuries, a rich and complex coastal Indian culture emerged on the lowlands surrounding the mountains. The economy revolved around hunting and gathering, with salmon and marine mammals forming the staples of the coastal villages. The tribes made forays deep into the mountains during summer, a fact attested to by numerous finds of stone points in the high valleys.

Coastal Indian culture revolved around permanent winter villages made up of cedar longhouses. Summer excursions were made to hunt elk or gather shellfish. Native carvers constructed masks that are now considered high art. These masks are still used in religious ceremonies that reaffirm the ties between the tribe and the natural world. Prominent families added to their prestige by holding lavish potlatches, during which they gave away most of their possessions as gifts. In many respects, the Indians of the Northwest Coast were quite similar culturally to the Europeans who explored the area much later.

The Indians of the Olympic Peninsula are organized into a number of distinct bands that persist to this day. On the eastern side of the peninsula, the Twana people are divided into the Quilcene (meaning “saltwater people”) and the Skokomish (meaning “fresh-water people”). To the north, the S’Klallam tribe includes the coastal element found near Sequim as well as the more inland-oriented Elwha band. The Makah of the Cape Flattery area were perhaps the most ocean-oriented of the tribes, and relied heavily on marine mammals for their subsistence. The Quileute, Queets, and Quinault people to the south also hunted marine mammals but based their economies most heavily on bountiful runs of steelhead and salmon.

The Olympic Forests

One of the hallmark features of Olympic National Park are its vast expanses of unbroken forest. Some of the stands have not been greatly disturbed in more than 1,000 years, and the result is an old-growth community of outstanding diversity. Some of the largest specimens of coniferous trees in the world are found here, with boles that approach 20 feet in diameter and crowns that soar more than 200 feet into the sky. Beyond the borders of the park, state and private timberlands are an ecological wasteland dedicated solely to the production of timber products. In this area, the widespread clear-cutting and resulting forest fragmentation are destroying the habitat of the endangered spotted owl, and as a result the barred owl is moving in, further displacing the spotted owls from their natural habitat. It is only through the foresight of early conservationists that some of the primeval Olympic forest has survived.

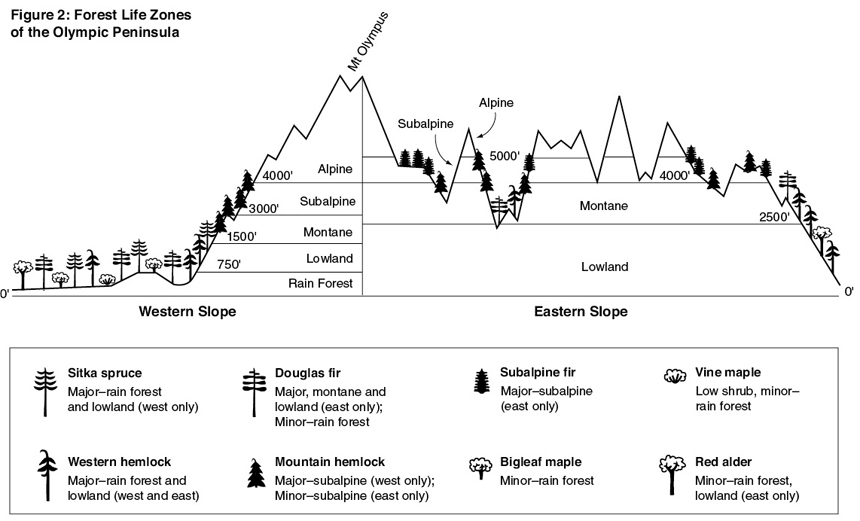

The lowland valleys of the west are covered in a rain forest of enormous ecological value. This area receives an average of more than 12 feet of rain annually, most of which falls during winter months. Morning fogs roll in from the ocean, sustaining the mighty Sitka spruce, which grows only within 20 miles of the ocean. These fogs are critical to this species of tree because it cannot control the amount of water that it loses to transpiration. Bigleaf and vine maple are prominent hardwoods, and western hemlock, Douglas fir, and red cedar round out the important overstory species.

A lush growth of epiphytes, or plants that grow on tree surfaces, suffuses the understory of the rain forest with a greenish glow. Club mosses, lichens, and licorice ferns all make their home on living and dead trees. Saplings and shrubs grow from the mat of mosses that covers fallen tree trunks, which are thus known as nurse logs. The abundance of dead wood and complex structure of the forest canopy creates a large number of ecological niches for mammals and birds. Roosevelt elk maintain the openness of the rain forest by browsing out brush and young hemlock saplings, which in turn encourages the growth of herbaceous ground cover such as oxalis and violets.

Moving up in elevation, a lowland forest dominates the lower slopes of the foothills (see Figure 2). Western hemlock is dominant here, although Douglas fir may be prevalent in areas with a history of fire. This forest type also occupies all of the low country on the eastern side of the peninsula. It grades into a montane forest on the middle slopes. This forest type has little understory growth and occupies well-drained soils. Silver firs show up as the montane forest becomes subalpine in character. Near timberline, lingering snows determine the distribution of trees, and the conical mountain hemlock and subalpine fir predominate. These spire-shaped trees shed winter snows easily by virtue of their tall and slender growth form.

Above timberline, plant communities are strongly determined by minute differences in microclimate. The few conifers that grow here are sculpted into low-growing krummholz forms by windblown ice and snow. Lingering snowfields may promote the growth of such plants as avalanche lilies or bistort, and in extreme cases may prevent any plants from taking root at all. In contrast, well-drained sites may be as desiccated as a desert, and only water misers like shrubby cinquefoil can survive in such places. Other plants, such as phlox and penstemon, specialize in colonizing cracks in the rock itself, where little or no soil is present. In general, timberline habitats are dominated by lush swards dotted with wildflowers, although a kind of alpine desert can be found in places in the northeast corner of the mountains.