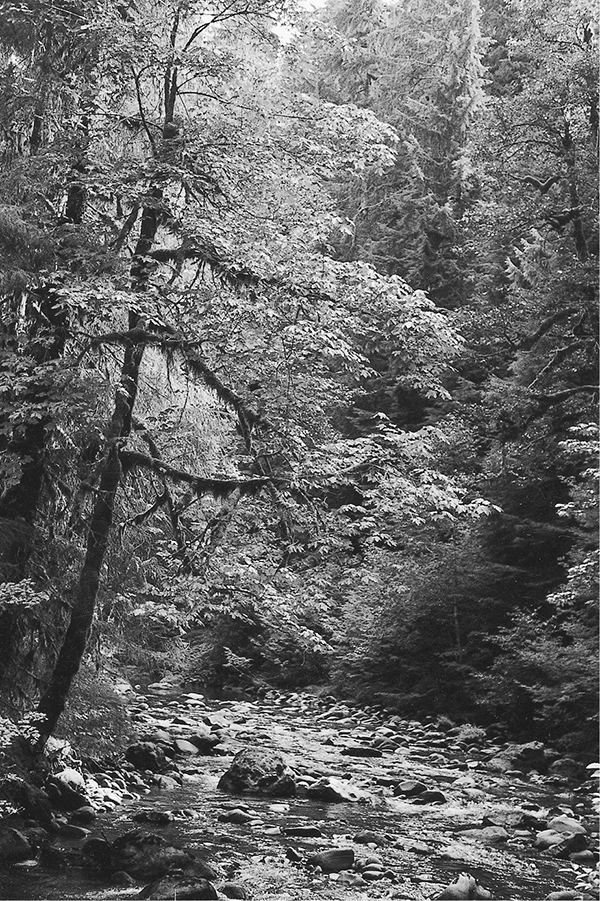

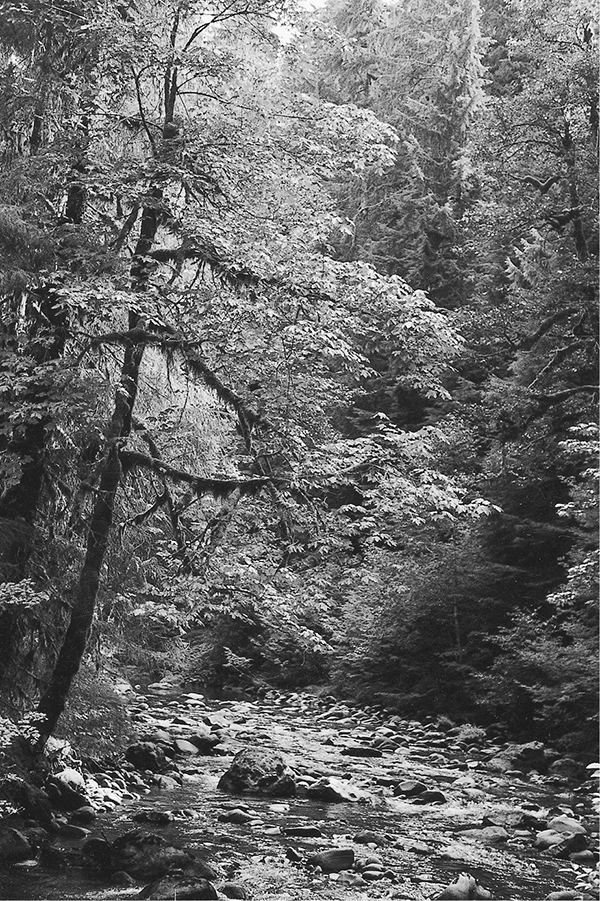

The North Fork of the Sol Duc River

A Few Words of Caution

Weather patterns in the Olympic Mountains can change frequently and without warning. Cold temperatures can occur even during the height of summer, and nighttime temperatures routinely dip into the 40s and even 30s on clear nights. Thunderstorms may suddenly change cloudless days into drenching misery, so carry appropriate rain gear at all times. Ponchos are generally sufficient for day hikes, but backpackers should carry full rain suits: water from drenched vegetation will quickly soak travelers who rely solely on ponchos for protection. Snowfall is always a distinct possibility in the high country, and hikers on overnight expeditions should carry clothing and gear with this possibility in mind. Detailed short-range forecasts are available at ranger stations and are usually reliable.

In general, snows linger in the high country into mid-June. This month traditionally receives the heaviest rainfall of the summer, with drier weather coming in late July and August. The first snowstorms visit the high country in mid-October, and by the end of this month a deep blanket of snow may cover the passes. Hikers who head for the high country in early summer should check with local rangers for current trail conditions. In many cases, ice axes and crampons will be required, especially on high passes with northern exposures. October marks the beginning of the rainy season in the park, and the drizzle does not let up until late April.

Drinking water from the pristine streams and lakes of the Olympic Peninsula is quite refreshing, but all such sources may contain a microorganism called Giardia lamblia. Giardia is readily spread to surface water supplies through the feces of mammals and infected humans, causing severe diarrhea and dehydration when ingested by humans. Water can be rendered safe for drinking by boiling it for at least five minutes or by passing it through a filter system with a mesh no larger than 2 microns. Iodine tablets and other purification additives are not considered effective against giardia. No natural water source is safe, and a single sip of untreated water can transmit the illness. Symptoms (gas, cramps, nausea, and diarrhea) usually appear within three weeks and demand medical attention.

Many of the wild animals in Olympic National Park may seem almost tame. In the absence of hunting, these creatures have lost their natural fear of humans. However, they remain wild, finely attuned to their environment and sensitive to human disturbance. Feeding wildlife human food may cause the animal digestive problems and may erase the wild instincts that keep the animal alive during times of scarcity. Black bears are particularly troublesome in their quest for human food. Campers must hang their food in a tree or from a cache wire, at least 10 feet above the ground and 6 feet away from the tree trunk. In some areas, special bear-resistant food canisters must be used. These bears are able climbers and will raid food containers that are hung too close to the trunk. Other animals are more of a nuisance than a danger. Deer and mountain goats often hang around campsites and try to steal sweat-soaked clothing and saddle tack. At higher elevations, rodents dwelling in rockslides may chew their way into a pack in search of food or salt. Along the Olympic coastline, raccoons have become crafty camp raiders in their opportunistic quest for food.

The Olympic Peninsula has one of the highest mountain lion populations in the nation. Because of their reclusive habits, they are rarely seen by hikers. However, they can present a real threat if encountered at close range. The current wisdom is that hikers encountering a cougar should behave aggressively in order to scare it off. Remain standing and never turn your back on a cougar or attempt to run away. Such behavior may incite an attack. Report all sightings at the nearest ranger station.

Fording Streams and Rivers

There are only a few places in Olympic National Park where trails cross major rivers without the benefit of a bridge. Bear in mind, however, that footlogs and bridges can be washed out during floods. Unbridged stream crossings are labeled as fords on the maps provided in this book. Streams are typically highest in early summer, when snowmelt swells the watercourses with silty discharge. Water levels also rise following rainstorms. Glacial rivers on the western side of the peninsula rise on warm afternoons as the meltwater from the glaciers surges downstream. Stream crossings should always be approached with caution; even a shallow stream can harbor slippery stones that can cause a sprained ankle or worse. However, wilderness travelers can almost always make safe crossings by exercising good judgment and employing a few simple techniques.

When you get to the water’s edge, the first thing you’ll probably think is, “This is going to be really cold!” It will be even colder if you try to cross barefooted. Since most folks don’t like to hike around in wet boots all day, we recommend bringing a pair of lightweight canvas sneakers or river sandals specifically for the purpose of fording streams. Wearing something on your feet will prevent heat from being conducted from your feet to the stream cobbles and will give you superior traction for a safer crossing. Walking staffs add additional stability when wading streams. Some manufacturers make special staffs for wading with metal tips, and some even telescope down to manageable proportions. If you use one of these, remember not to lean too hard on it; your legs should always bear most of the burden.

Before entering the stream, unclip your hip belt and other restrictive straps; having the straps undone could save you from drowning. Water up to knee-depth can usually be forded without much difficulty; midthigh is the greatest safe depth for crossing unless the water is barely moving. Once you get in up to your crotch, your body starts giving the current a broad profile to push against, and you can bet that it won’t be long before you are swimming.

When wading, discipline yourself to take tiny steps. The water will be cold, and your first impulse will be to rush across and get warm again, but this kind of carelessness frequently results in a dunking. While inching your way across, your feet should seek the lowest possible footing, so that it is impossible to slip downward any farther. Use boulders sticking out of the streambed as braces for your feet; these boulders will have tiny underwater eddies on their upstream and downstream sides, and thus the force of the current against you will be reduced by a fraction. When emerging from the water, towel off as quickly as possible with an absorbent piece of clothing. If you let the water evaporate from your body, it will take with it additional heat that you could have used to warm up.

Some streams will be narrow, with boulders sticking up from the water beckoning you to hopscotch across without getting your feet wet. Be careful, because you are in prime ankle-spraining country. Rocks that are damp at all may have a film of slippery algae on them, and even dry rocks might be unstable and roll out from underfoot. To avoid calamity, step only on boulders that are completely dry, and do not jump onto an untested boulder, since it may give way. The best policy is to keep one foot on the rocks at all times, so that you have firm footing to fall back on in case a foothold proves to be unstable.

The North Fork of the Sol Duc River

How to Follow a Faint Trail

Some of the trails that appear on maps of the Olympic Peninsula are quite faint and difficult to follow. Visitors should have a few elementary trail-finding skills in their bag of tricks, in case a trail peters out or a snowfall covers the pathway. A topographic map and compass—and the ability to use them—are essential insurance against disaster when a trail takes a wrong turn or disappears completely. There are also a few tricks that may aid a traveler in such a time of need.

Maintained trails on the Olympic Peninsula are marked in a variety of ways. Signs bearing the name of the trail are present at most trail junctions. The trail signs are usually fashioned of plain wood, with the script carved into them. They sometimes blend in well with the surrounding forest and may go unnoticed at junctions where a major trail meets a lightly traveled one. These signs sometimes contain mileage information, but this information is often inaccurate.

Along the trail, several kinds of markers indicate the location of maintained trails. In forested areas, old blazes cut into the bark of trees may mark the path. In spots where a trail crosses a gravel streambed or rock outcrop, piles of rocks called cairns may mark the route. Cairns are also used in windswept alpine areas. These cairns are typically constructed of three or more stones placed one on top of the other, a formation that almost never occurs naturally.

Mountain goat at Appleton Pass

In the case of an extremely overgrown trail, markings of any kind may be impossible to find. On such a trail, the techniques used to build the trail serve as clues to its location. Well-constructed trails have rather wide, flat beds. Let your feet seek level spots when traveling through tall brush, and you will almost always find yourself on the trail. Old sawed logs from previous trail maintenance can be used to navigate in spots where the trail bed is obscured; if you find a sawed log, then you must be on a trail that was maintained at some point in time. Switchbacks are also a sure sign of an official trail; wild animals travel in straight lines and rarely zigzag across hillsides.

Trail specifications often call for the clearing of all trees and branches for several feet on each side of a trail. In a forest situation, this results in a distinct “hall of trees” effect, where a corridor of cleared vegetation extends continuously through the woods. Trees grow randomly in a natural situation, so a long, thin clearing bordered by tree trunks usually indicates an old trail bed. On more open ground, look for trees that have lost all of their lower branches on only one side. Such trees often indicate a spot where the old trail once passed close to a lone tree.

When attempting to find a trail that has disappeared, ask yourself where the most logical place would be to build a trail given its source and destination. Trail builders tend to seek level ground where it is available, and often follow the natural contours of streamcourses and ridgelines. Bear in mind that most trails avoid up-and-down motion in favor of long, sustained grades culminating in major passes or hilltops. Old trail beds can sometimes be spotted from a distance as they cut across hillsides at a constant angle.