A number of empirical studies of on-the-job excellence have clearly and repeatedly established that emotional competencies — communication, interpersonal skills, self-control, and so on — "play a far larger role in superior job performance than do cognitive abilities and technical expertise" (Goleman, p. 320). Yet most of the emphasis in the education and training of engineers is placed upon purely technical education.

Notwithstanding some brilliant exceptions, intelligence, academic training, technical knowledge, and circumstantial expertise alone are not major determinants in the success or failure of engineers in the workplace. For the most part, engineers are or can quickly become adequately capable in these areas. If technically incapable, they almost certainly would have been discharged from the system, either by themselves or by others, long before they became employed engineers. Generally, such skills and traits as communication, confidence, group and interpersonal effectiveness, motivation, pride in accomplishments, adaptability, leadership potential, inquisitiveness, integrity, and emotional control are exhibited by the most successful employees, just as with the most successful among engineers.

It should be obvious enough that a highly trained technical expert with a good character and personality is necessarily a better engineer and a great deal more valuable as an employee than a sociological freak or misfit with the same technical training. This is largely a consequence of the elementary observation that in a normal organization one cannot get very far in accomplishing anything worthwhile without the voluntary cooperation of one's associates; and the quantity and quality of such cooperation is determined by the "personality factor" as much as anything else. Added to this need for one-on-one cooperation are all sorts of "soft" characteristics from understanding contemporary society to following ethical behavior — all of which can add up to benefits for yourself and your employer far beyond ordinary technical contributions.

The following "laws" are drawn up from the purely practical point of view. As in the two preceding sections, the selections are limited to rules that are frequently violated, with unfortunate results, however obvious or stale they may appear.

This is rather a comprehensive quality but it defines the prime requisite of personality in any type of industrial organization. No doubt this ability can be achieved by various formulas, although it is probably based mostly upon general, good-natured friendliness, together with fairly consistent observance of the "Golden Rule." The following "do's and don'ts" are more specific elements of such a formula.

It is a mistake, of course, to try too hard to get along with everybody merely by being agreeable or even submissive on all occasions. Somebody will take advantage of you sooner or later, and you cannot avoid trouble simply by running away from it. Do not give ground too quickly just to avoid a fight, when you know you're in the right. If you can be pushed around easily the chances are that you will be pushed around. Indeed, you can earn the respect of your associates by demonstrating your readiness to engage in a good (albeit non-personal) fight when your objectives are worth fighting for. Shakespeare put it succinctly in Polonius's advice to his son (in Hamlet): "Beware of entrance to a quarrel, but being in, bear't that the opposed may beware of thee."

Like it or not, as long as you're in a competitive business you're in a fight; sometimes it's a fight between departments of the same company. As long as it's a good clean fight, with no hitting below the belt, it's perfectly healthy. But keep it to "friendly competition" as long as you can. In the case of arguments with your colleagues, it is usually better policy to settle your differences "out of court," rather than to take them higher for arbitration.

Likewise, in your relations with subordinates it is unwise to carry friendliness to the extent of impairing discipline. Every one of your employees should know that whenever they deserve a reprimand, they'll get it, every time. The most rigid discipline is not resented so long as it is reasonable, impartial, and fair, especially when it is balanced by appropriate praise, appreciation, and compensation. At the extreme, there may well be times when firing or transferring an employee is the best course of action, both for the person involved and for the company. If you do not face your issues squarely, someone else will be put in your place who will.

In the long run there is hardly anything more important to you than your own self-respect, and this alone should provide ample incentive to maintain the highest standards for honesty and sincerity of which you are capable. But, apart from all considerations of ethics and morals, there are perfectly sound business reasons for conscientiously guarding the integrity of your character.

The integrity to which we refer is easily described: if you have high personal integrity, you are honest, morally sound, trustworthy, responsible, and sincere. The priceless and inevitable reward for uncompromising integrity is confidence: the confidence of associates, subordinates, and outsiders. All transactions are enormously simplified and facilitated when your word is as good as your bond and your motives are above question. Confidence is such an invaluable business asset that even a moderate amount of it will easily outweigh any temporary advantage that might be gained by having lost it.

A most striking phenomenon in an engineering office, once it is pointed out, is the transparency of character among members who have been associated for any length of time. In a surprisingly short period individuals are recognized, appraised, and catalogued for exactly what they are, with far greater accuracy than they usually realize. This makes anyone appear downright ludicrous when assuming a pose or trying to convince us that they are something other than they are. As Ralph Waldo Emerson puts it: "What you are . . . thunders so that I cannot hear what you say to the contrary." Therefore, it behooves you to let your personal conduct, overtly and covertly, represent the very best practical standard of personal and professional integrity by which you would like to let the world judge and rate you.

Moreover, it is morally healthy and creates a better atmosphere if you will credit the other person with similar standards of integrity. The obsessing and overpowering fear of being cheated is a common characteristic of substandard personalities. This sort of psychology sometimes leads one to credit oneself with being impressively clever when one is simply taking advantage of those who are more considerate and fair-minded.

In order to avoid any misunderstanding, it should be granted here that the average person, and certainly the average engineer, is by no means a low, dishonest scoundrel. In fact, the average person would violently protest any questioning of his or her essential honesty and decency, perhaps fairly enough. But the average person will often compromise whenever it becomes moderately uncomfortable to live up to his or her obligations. This is hardly what is meant by integrity, and it is difficult to base even moderate confidence upon the guarantee that you will not be deceived — unless the going gets tough.

Upon becoming a member of the engineering profession, you accepted the responsibility of a professional as well as any liability that accompanies that responsibility, be it personal, professional, or corporate. Many engineers pretend that they can hide behind their employer's or their department's shield, or that they are powerless, mere cogs in the machinery, even if, or especially if, something goes haywire. Although environmental, consumer, and product safety concerns are every individual's responsibility, an engineer, perhaps more than anyone, is uniquely positioned with the power and knowledge to create, identify, avoid, and correct such problems — an incongruous reality. Regardless of the size of your employer, never forget that, in the end, you contribute to making decisions, whether the results are good, bad, or catastrophic.

All this responsibility and liability will tempt you towards, but must not lead you to inaction and indecision. You needn't be unreasonably anxious; you are in your position as an engineer presumably because you have or can somehow bring to bear the training, knowledge, and experience to identify and judge the risks inherent in doing your business. Do your job responsibly, and you minimize liability all around. In this regard you will serve yourself, your employer, and your profession well if you follow a few simple guidelines:

Despite the usual ambiguities and everyday quandaries of engineering, ethical behavior usually comes naturally to engineers. Societal values — the basis for ethics — are ingrained. On the other hand, many times the ethical problems encountered in engineering practice are very complex and involve conflicting ethical principles (Fleddermann, p. 3). The accounts of many well-known cases of injurious product failures and tragic man-made disasters prove the point.

It should be observed that having the courage of your convictions includes having the courage to do what you know to be right, technically as well as ethically and morally, without undue fear of possible criticism or of the need to explain your actions. If your reasons for your actions are sound, you should not worry about having to defend them to anyone; if they're not sound you'd better correct them promptly, instead of building up an elaborate camouflage.

Understand, you are ill-advised to martyr yourself for every controversial matter in which you strongly believe. Martin Luther King, Jr. said: "If a man hasn't discovered something that he will die for, he isn't fit to live." True enough, but Oscar Wilde said: "A thing is not necessarily true because a man dies for it." Martyrdom only rarely makes heroes, and in the business world, such heroes and martyrs alike often find themselves unemployed.

Knowing what is ethically right, both for you and for your company, and then acting appropriately is the key. Professional societies offer good places to start with their codes of ethics, some of which are appended in this book.

Permissiveness and dress codes aside, your appearance probably has a far greater influence on how you are viewed by those around you than you could ever imagine. Bear this in mind when you define and present your workplace image. Three rules of thumb will serve you well in this regard.

Despite the wide range of acceptable personal appearance within any one office, and the vastly greater range to be found in society overall, it's hard to argue against these common-sense points.

Of course, we all know some very good engineers who are oblivious to such details. You can be sure that their apathy in this regard has been noted by those around them, if not explicitly, certainly subconsciously. Likewise, we all know some "wild" ones. They all must accept whatever the consequence is of their personal appearance, whether they like it or not, and so must you.

You will be well served if you simply avoid using profane language. Not using profanity will never be offensive to anyone. On the other hand, using profanity may well be offensive, even without your knowing it.

To be sure, obscene and vulgar language is routinely heard in some circles. Unfortunately, in the professional workplace, such language is sometimes used for its "effect." Some think it a mark of power, strength, or vigor. The trouble in using profanity is that its actual effect is known only to the listener, who may conclude something quite different about the speaker from what was intended. Regardless, blatantly obscene language serves no one properly, and a really foul mouth will generally inspire nothing but contempt.

There is simply no room in the workplace for harassment or discrimination of any kind. Blatant infractions will get employees and employers into big trouble, as most people know, but big trouble can also come from subtler forms of these unacceptable behaviors. The "harmless" off-color joke and slightly misguided comment can also offend, and are not acceptable.

Of course, no one likes the self-appointed police officer who is constantly on the look-out for rule violations or who constantly cautions colleagues about workplace behavior. Confronting a colleague or subordinate on such matters must itself be handled discretely and delicately. Your best course of action, whether you are a target or an observer of suspected harassment or discrimination, depends upon the circumstances. You may choose to informally approach the alleged offender directly, but any formal discipline should be handled together with your manager, personnel department, or both.

Be careful about who gets copies of your letters, memos, and messages, in whatever form or medium they are created, especially when the interests of other departments are involved. Engineers have been known to broadcast memoranda containing damaging or embarrassing statements. Of course it is sometimes difficult, especially for novices, to recognize the "dynamite" in such a document. But, in general, it is apt to cause trouble if it steps too heavily into another's domain or reveals serious shortcomings on anybody's part. If it is to be distributed widely or if it concerns manufacturing or customer difficulties, you'd better get a higher authority to review and approve it before it goes out.

Once you have issued something in writing, despite your best attempts to the contrary, you will have relinquished control of its distribution and its life. To be safe, you had better assume that your documents might go to anyone and that they will exist forever. Compose them accordingly.

As the worst conduct in this regard, misplaced verbal assaults can cause enough mischief, but putting such emotions into writing can cause way more than enough. Anger, malice, disrespect, and ridicule toward another will be remembered in written documents forever, which may be long after you wish they had been forgotten.

Most of us have used the office copier or borrowed a shop tool for our personal use, and we trust that hardly anyone would ever make anything of it. Nevertheless, whenever you use your company's property, equipment, or supplies for anything other than company business, you risk suspicion. Furthermore, your employer has every right to investigate your behavior, including examining all of your "personal" domain at work (for it is not really personal) for any evidence of misconduct.

To be sure, most employees, absent obvious transgressions in this regard, should be held above suspicion, and the first examples above are probably harmless enough. Nevertheless, for what little you will likely gain by appropriating anything of your employer's assets, in the end it hardly seems worth the risk, even if only to your integrity.

It is the rare engineer who has a single employer for a whole career, and employers understand this. So it follows that it is unreasonable to expect engineers to accept becoming useless to other potential employers, however invaluable they may have become to their current employer. If your skills and knowledge are valuable only to your current employer, you are in trouble. Sooner or later, for one reason or another, your employer will no longer be interested in buying those skills, and you will have no place else to sell them.

Obsolescence is bad business for employers as well as employees. It is costly for employers to disposition the obsolete, and to hire or develop employees with the skills that the departed should have been developing all along. Therefore, for the benefit of your employer, you should also make this situation unequivocally clear to your subordinates, then you should do all you can to counsel and support them in this regard.

Be an adherent and a proponent of life-long learning. This doesn't mean constant formal training — university classes, seminars, short courses, company-sponsored training — although some of these are a necessary part of a life-long employability plan. It also means taking more than a passing interest in your field by reading sales literature, trade magazines, and professional publications, and attending trade shows and professional conferences. You must find ways to keep up-to-date on new technology in your field regardless of how much or how little your employer supports you, and if you wait for someone to offer you the opportunity, you are just waiting for your own obsolescence. All of this will require sacrificing some personal time and, perhaps, some personal expense as well. Simply put, not all employers will accept the full burden of employees' continuing education. The effort and dedication required to remain employable is in every engineer's best interest.

Engineers and engineering managers need not be students of psychology — most are disinclined anyway. Nevertheless, it is enlightening to appreciate that people, including yourself, behave as they do not so much because they want to behave that way, but rather because that is how they are. Fundamentally, people see and react to things, and judge and decide things quite differently from one another. Even without fully understanding different personality types, simply recognizing that people are remarkably different will help you accept different personalities as normal, and not to view them as somehow wrong.

Among the important decisions for engineers to make for themselves or their subordinates are when and how much managerial and administrative responsibility is appropriate. It has been assumed in all the foregoing that any normal individual will be interested in either: (a) advancement to a position of greater responsibility, or (b) improvement in personal effectiveness as regards quantity and quality of accomplishment. Either of these should result in increased financial compensation and satisfaction derived from the job. As to item (a), it is all too often taken for granted that increased executive and administrative responsibility is a desirable and appropriate form of reward for outstanding proficiency in any type of work. There should be other ways of rewarding an employee for outstanding accomplishment, for such rewards may be a mistake from either of two points of view:

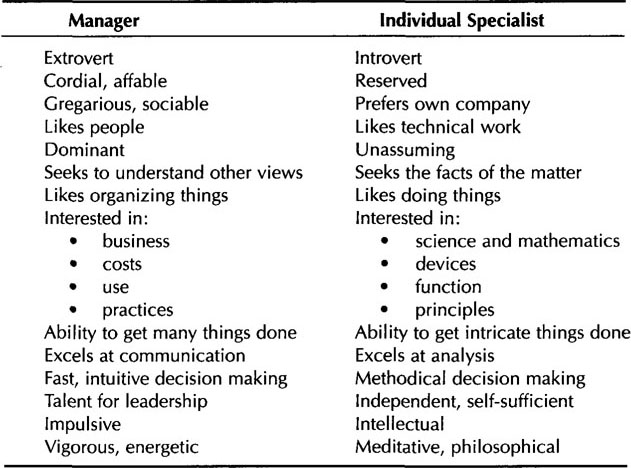

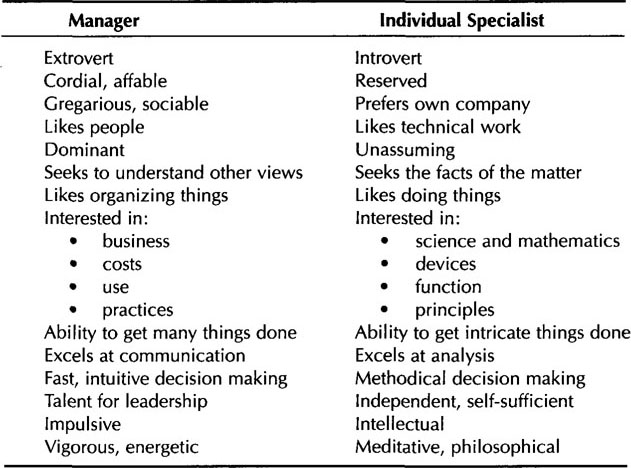

These facts should therefore be considered carefully by the person threatened with promotion and by the person about to do the promoting. It is not always easy, however, to decide in advance whether you, or the employee in question, would be happier and more effective as more of a manager and less of an individual worker, or vice versa. There is no infallible criterion for this purpose but it will be found that, in general, the two types are distinguished by the characteristics and qualities listed in the accompanying table.

Although nobody fits neatly into one column or the other, a preponderance of engineers has the qualities of the specialist column. This seems to be especially true for engineers just starting their careers; most will have been drawn to engineering because they have these characteristics. This, no doubt, is the source of the conventional stereotype of the engineer. But beware — you do a grave disservice to those who you assume fit this stereotype simply because they are engineers. Everyone is a unique blend. Furthermore, none of these characteristics should be considered better or worse than its counterpart, but each is quite clearly different from the other.

In reality, nobody successfully moving through an engineering career can avoid management and administration altogether. These are necessary parts of all job descriptions, and a certain amount of managing projects and supervising others is satisfying for all but the most narrow-minded technologist. Further, as time goes by, many engineers find their interest in management changing, often increasing as their career matures.

CHARACTERISTIC QUALITIES

OF MANAGERS OR INDIVIDUAL SPECIALISTS Manager

Although certain personality types are more disposed to become managers in their careers, and some personality characteristics seem to be more common than others in successful managers, any personality type can be that of a successful manager, and no personality characteristic precludes someone from managerial success. We all know the reserved, introspective, or intellectual, yet highly effective manager. What makes a successful manager, and whether or not a person will thrive as a manager, is more complicated than simply matching up a few traits. Indeed, those who choose to become managers can become successful regardless of their traits by manipulating their situations and selecting their styles to make the best use of strengths and to de-emphasize weaknesses. Perhaps as important as anything, upon becoming, or in anticipation of becoming, a newly promoted manager, anyone is well advised to seek the knowledge and training required to succeed. Time and again it is all too clear how seriously ill-equipped many engineers, with their technical training alone, are to be managers.

As regards analyzing yourself and your subordinates, some final good advice for anyone is: Do what you do best; you will also be the happiest. Try to improve your best traits and make them the most visible. Of course, try to improve anything of yourself that people could consider substandard, but trying to become expert, or even proficient at something for which you have little natural talent is futile. It is often better to minimize the harm by making it unnecessary in your job or invisible in your behavior. Analyze yourself and then emphasize the positive!