Starting from unlikely, even utopian origins in the Weimar spaceflight movement, and ending even more strangely with ineffective weapons and emaciated slaves, the German Army rocket program and its Peenemünde center without a doubt changed the face of the twentieth century.

—MICHAEL J. NEUFELD, THE ROCKET AND THE REICH (1995)

Even as England was suffering Germany’s V-1 barrage, rumors swirled about the next super-weapon in Hitler’s arsenal. “Britons pondered the possibility of worse to come,” the New York Times reported that summer of 1944, “perhaps huge explosive rockets. The horrifying prospect that Germany’s threatened new secret weapon might be a ten-ton explosive rocket—a robot bomb ten times the size of the V-1, or ‘buzz bomb,’ now being used against England—’may not be sheer propaganda’ a commentator at an Allied advance command post said.” British intelligence, having secured photos of a test V-2, understood its engineering structural and destructive capacity and surmised that the rocket was to be used against London. Another key (and essentially correct) assumption on which the Allies based their strategy was that the V-2 had a range of 210 miles.

Allied troops pushed to find and destroy every potential V-2 launch site within a 210-mile radius of London, a task that took them across the northern coast of France and into Belgium and Holland. In his usual forthright fashion, British prime minister Winston Churchill pronounced a German V-2 rocket attack and another Luftwaffe blitz like the one of 1940–41 the direst threats to his nation’s survival.

As the Allies raced to suppress the German V-2 campaign even before it began, the war-ravaged British capital was on constant high alert. Rushed by the devastating German loss on D-day, von Braun conducted a missile test on June 22, during which his V-2 crossed the Kármán line, the boundary between Earth’s atmosphere and outer space, reaching an altitude of 109 miles—and became the first man-made object to reach outer space.

Despite von Braun’s stunning success, the German High Command was becoming impatient with progress on the V-2, specifically its intricate engineering and the unending need for technical refinements. Too many V-2s were breaking up on entry. On August 6, 1944, Heinrich Himmler, consumed with frenzied urgency, installed SS general Hans Kammler as director of the V-2 project, with marching orders to prepare for utilization of the rocket “as quickly as possible.” Dictatorial, brusque, and a fanatical adherent of Nazi ideology, the hard-nosed Kammler clashed with many at Peenemünde. Ironically, his insistence that he be granted military command of what he declared would be Germany’s most glorious campaign delayed the V-2 offensive even more. Von Braun loathed Kammler, but continued his trial-and-error experiments on the V-2. Even though von Braun thought Kammler dangerous, he nevertheless advised his superior officer on how to speed up mass production. Fearful of the Armaments Ministry, von Braun had learned how to obey orders without challenging assumptions. As the German Army became desperate for men of fighting age, von Braun found a noncombat management position for his younger brother, Magnus, at the Mittelwerk compound, where meaningful jobs came with one of the Third Reich’s highest-priority security clearances.

On August 29, Hitler ordered V-2 attacks to begin as soon as possible. The Allies continued to methodically target suspected V-2 launch sites within a 210-mile launch radius of London, but what they didn’t know was that Dornberger had specified early on that the V-2 launch apparatus be mobile, able to be quickly put in position, utilized, and then moved elsewhere for another round of launches, frustrating Allied efforts to track the weapons.

On September 8, 1944, the Nazis fired a V-2 rocket at Paris, which had been liberated by the Allies just two weeks before. This rocket landed near the Porte d’Italie in the French capital, causing no casualties. Within four minutes of takeoff, a second V-2 came screaming back to Earth. This ballistic missile killed six people and changed the world forever. The moment the officer in charge shouted, “Zundung!” (ignition) represented the culmination of more than twenty-five years of German engineering brilliance, technological innovation, military desperation, and rank brutality. At just under forty-six feet in length, the V-2 weighed over fourteen tons, including about one ton of explosives. Following designs innovated by Oberth and von Braun, it lifted off when liquid fuel and oxidizer were pumped into the combustion chamber at the rate of thirty-three gallons per second. After about one minute aloft, with the fuel depleted, the rocket traveled through space at an altitude of just under fifty miles, at which point it arced ballistically toward its target, reaching speeds of up to thirty-six hundred miles per hour. Midcourse corrections had been made at Peenemünde with three components: sophisticated gyroscopes that measured the movements of the rocket; an onboard analog computer that calculated necessary changes; and rudders that could be adjusted by the computer.

The following day, a detail of German soldiers surprised the residents of a quiet suburban neighborhood in The Hague, knocking on doors and ordering the occupants to vacate immediately. The next day, military vehicles hauling V-2s aboard Meillerwagen (mobile launch platforms) pulled into the now-deserted Dutch streets with orders to launch two V-2s at London. Well trained by Dornberger, the mobile units had the first combat V-2 rocket in position within an hour. Within another half hour, their job would be done.

Of the London-bound rockets, one did no serious damage, but the other wreaked havoc in the western suburb of Chiswick. John Clarke was six years old and playing in the bathroom of his family’s home when the rocket struck, causing his building to crumble and sending a shard of metal from the V-2 through his hand. His three-year-old sister, sleeping in the next room, was killed. “There wasn’t a mark on Rosemary,” Clarke, who was permanently deafened in the attack, remembered sixty years later. “The blast goes up and comes down in a mushroom or umbrella shape, but in the process of that my sister’s lungs collapsed. She was deprived of air.” An off-duty serviceman walking nearby and a woman sitting in her house were also killed, making a total of three deaths from the first V-2 strike on England.

That evening, the true dawn of the missile rocket age, von Braun was informed of the successful launches on Paris and London. Witnesses at Peenemünde provided different versions of his initial reaction to the fulfillment of his dream. One of his loyal secretaries, Dorette Kersten Schlidt, recalled the mood in the office. “Von Braun was completely devastated,” she said. “In fact never before or afterward have I seen him so sad, so thoroughly disturbed. ‘This should never have happened,’ he said. ‘I always hoped the war would be over before they launched an A-4 [the scientists’ name for the V-2] against a live target. We built our rocket to pave the way to other worlds, not to raise havoc on earth.’”

Another colleague at Peenemünde remembered the night much differently. “When the first V-2 hit London, we had champagne,” he noted. “And why not? We were at war . . . we still had a Fatherland to fight for.” Perhaps von Braun was truly remorseful at the stark reality of his invention killing civilians; after all, his interest in rocketry had begun in dreams of spaceflight. But once his V-2s began raining down on Britain, France, and later Belgium and the Netherlands, he crossed a damning threshold: the man who dreamed of the moon was now Hitler’s agent of mass destruction, working in a Europe imbued with sorrow and death.

At the time of the V-2 launches, about five million Germans had already been killed in the war. Nearly one in three Nazi servicemen would die in the bloody conflict. Allied bomber attacks sometimes killed thousands of people at a time. Nor was von Braun always a mere distant observer of the carnage that became commonplace during the Nazi reign of terror. At the wretched Mittelwerk factory, more than 10,000 slave laborers from the Dora-Mittelbau prison camp perished producing V-2 missiles, V-1 flying bombs, and other weapons. If von Braun wasn’t directly responsible for their deaths, he was certainly complicit. From September 1944 until the end of the war the following May, more than 4,300 V-2s were launched by the German Wehrmacht against allied targets, mostly in London, Antwerp, and Liege. These missiles killed an estimated 9,000 civilians and military personnel, caused serious injury to an additional 25,000, and damaged or destroyed over a million homes.

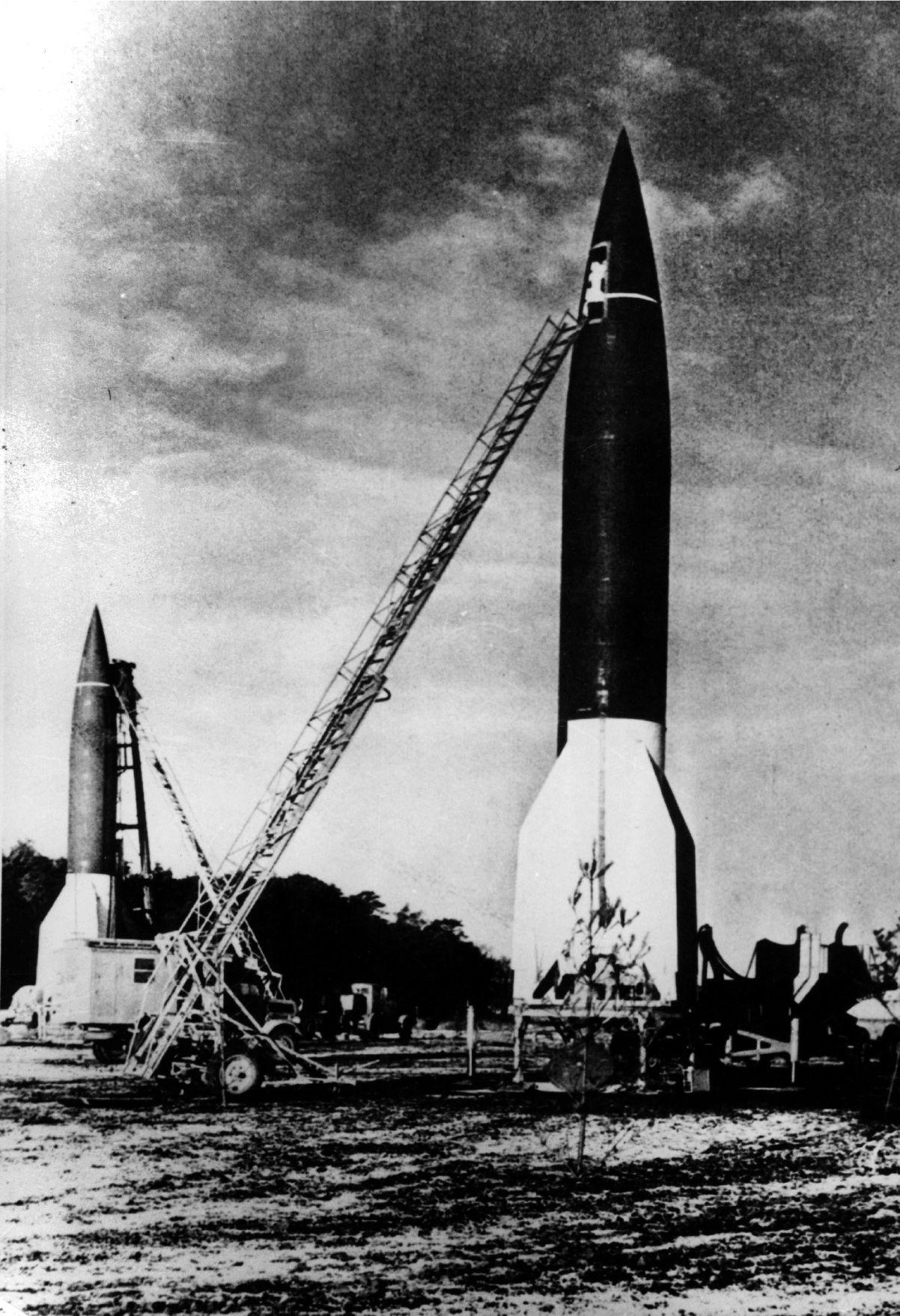

A V-2 rocket in launching position at Peenemünde (German Army Research Center) during World War II.

INTERFOTO/Alamy Stock Photo

So driven was von Braun by his quest for V-2 glory, and for Germany to win the war, that he grew inured to the chaos and loss his advanced work was causing. Like Lieutenant Colonel Nicholson in Pierre Boulle’s 1952 novel The Bridge over the River Kwai, von Braun was task driven, obsessed with completing a job no matter the cost. “With a satisfied eye he witnessed this gradual materialization,” Boulle wrote of Nicholson, “without connecting it in any way to humble human activity. Consequently, he saw it only as something abstract and complete in itself: a living symbol of the fierce struggles and countless experiments by which a nation gradually raises itself in the course of centuries to a state of civilization.”

Von Braun was convinced that rocketry was just that kind of symbol, elevating the technological excellence of a civilization. Much later, his convivial comments about the technical achievement of the V-2 betrayed no genuine anguish, only the arch observation that scientific breakthroughs since the fifteenth century had often begun in the sphere of weapons development. But the truth was that rather than elevating civilizations, his V-2 work for the Nazis degraded it, becoming nothing more than a tool by which a three-year-old British girl had been killed willy-nilly, and which would claim thousands more innocents to come. In that respect, Germany’s Wunderwaffe (miracle weapon) was no different from a simple club, hatchet, sword, or bayonet. Or, for that matter, the incendiary bombing raids the USAAF and RAF conducted on Germany.

Both versions of von Braun’s initial reaction to the launch of the V-2 on France, Belgium, and Great Britain might be entirely accurate. The enigmatic engineer often told people what they wanted to hear and showed the colors they hoped to see. If he was a hypocrite and accomplice, he believed, then so be it—that was how his rocket program had survived in the Third Reich. If he had an intense concern about the Holocaust happening around him, he never expressed it. Everywhere von Braun went in high Nazi circles after September 8, 1944, he was congratulated. With his broad shoulders, groomed hair, and splendid physique, gazing up in the air at parties with thoughtful self-importance, he was treated as the proud exemplar of German rocketry genius, and he possessed an exalted opinion of himself. Von Braun’s amoral hunger to construct rockets governed his embrace of an evil regime. Both during World War II and after, he accepted accolades as an engineering visionary who foresaw the potential of human spaceflight, never admitting that he was essentially a fast-track Nazi arms merchant who developed brutal weapons of mass destruction. In the late 1960s, as the United States was involved in a race with the Soviet Union to land a human on the moon first, humorist Tom Lehrer wrote a song about von Braun’s opportunistic approach to serving whoever would let him build rockets regardless of their purpose:

Don’t say that he’s hypocritical, say rather that he’s apolitical

“Once the rockets are up, who cares where they come down?

That’s not my department,” says Wernher von Braun.

Lehrer’s biting satire captured well the ambivalence of von Braun’s indifference on moral questions associated with the use of the V-2 and other rocket technology.

AFTER THAT FIRST September launch, German V-2s began striking targets in Great Britain at a rate of about two hundred per month. The hastily built rockets, however, were far from perfect. Some V-2s hit their targets but failed to explode. Others burst prematurely in the air, sending burning debris showering down for miles around, like spent fireworks. In October, the Third Reich launched V-2s on Antwerp, Belgium, determined to prevent that all-important European port from becoming an Allied stronghold. At the government level, British officials initially promulgated the fiction that ruptured gas pipes had caused the early V-2 damage, but the fact was that Whitehall didn’t want to release any information about the destruction that might be helpful to the Nazis. “The enemy,” Churchill recalled, “made no mention of his new missiles until November 8, and I did not feel the need for a public statement until November.”

The German propaganda announcement of V-2 attacks made headlines in the United States. Reporters searched for anyone knowledgeable to discuss rocket engineering. What did the V-2 mean? Did the United States have a similar program? One of the few Americans in a position to know was keeping a very low profile. Dr. Robert Goddard, then working on developing jet-assisted takeoff units for navy aircraft in Maryland, received intelligence on the V-2 that November, writing matter-of-factly in his diary entry from Annapolis, “V-2 type rocket appears to be of interest.”

Not surprisingly, Goddard felt threatened by von Braun’s engineering breakthroughs on the V-2, which made all previous rocketry trials seem quaint. Refusing to be crushed by the knowledge, though, within weeks he was echoing the Roosevelt administration’s efforts to promote a patriotic fallacy: that the V-2 had been copied directly from Goddard’s hundreds of static tests and earlier flight tests conducted at a ranch near Roswell, New Mexico. Starting early in 1945, articles in publications such as National Geographic Newsletter claimed that Goddard was the father not only of America’s infinitesimal rocket capability, but of Germany’s burgeoning efforts as well. This exaggeration took hold in the United States, despite the many basic technical points that separated Goddard’s last, lonely prewar rocket tests from the grand-scale work being done by the hundreds of scientists at Peenemünde. Even if the U.S. propaganda effort did a disservice to engineering history, it did spark a public demand for an increased American role in liquid-fueled rocketry and military missiles.

At the NACA headquarters in Washington, DC, located in a corner of the Navy building, leadership kept a close eye on the V-2. Described as the “Force Behind Our Air Supremacy,” the NACA research-and-development team tested highly sophisticated superchargers for high-altitude bombers such as the B-17 and B-24, as well as airfoils that are still being used in twenty-first-century aircraft manufacturing. While unable to develop anything as sophisticated as a V-2, the NACA engineers were responsible for a number of innovations that were vital to the war effort. Month by month, engineers at the NACA’s Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory, in Cleveland, Ohio, made vast improvements to fighter plane engines—for example, improving engine cooling capabilities in the B-29 Superfortress, a bomber essential to Pacific war strategy. The NACA’s first jet-engine test was performed in Cleveland’s Altitude Wind Tunnel. And when its Icing Research Tunnel opened in 1944, the notion of future manned space travel became more likely.

THERE IS NO record that Jack Kennedy, honorably discharged from the navy with the full rank of lieutenant on March 1, 1945, ever publicly commented on the V-2 rockets raining down on London. Like all Americans, he was happy that the V-1 and V-2 seemed to have appeared too late in the war to save the Third Reich, but having experienced the horror of war, he surely understood the weapon’s ghastly potential for mass destruction. In early 1945, he submitted an article to the Atlantic Monthly about the need for global peace, but the editors weren’t enthusiastic, and despite the intervention of his father, the piece was never published.

Like most returning veterans, Kennedy needed time to readjust. Seeing so much death had left the soldiers of his generation shell-shocked. He took his time, philosophically deliberating on his future and convalescing in the Arizona desert after his back operation. Eager to pay homage to his late brother, he edited a book of memorial essays about Joe’s short life, which would be privately published. But he also needed to contend with the stressful issue of claiming his new place as the eldest son in his family. With Joe Jr. gone, the expectation of a life in politics fell squarely on Jack’s shoulders. He told friends he felt obligated to fulfill his father’s longtime ambition to see one of his sons in high office, though at that point he scorned electoral politics as involving too much handshaking, baby kissing, and general pandering. Faced with paternal pressure and the prospect of having to abandon the more bookish and journalistic careers he’d contemplated before the war, Jack described plans for a future in public service, a vague goal with a range of possible options, including the diplomatic corps.

As a young intellectual, Kennedy showed promise, reserving special excitement for the field of international relations. His book Why England Slept had been a best seller and defined him as a thoughtful strategist with a natural affinity for global affairs. In person, Jack was known for his sense of humor, loving to laugh while downing a comradely glass of beer. Never humble but eager for self-improvement, he unquestionably had the kind of bright curiosity and original, analytical mind that made a good basis for a political career. But a certain indefiniteness was also a part of his personality. He could occasionally be high-strung, he was frequently in poor health, and he was always an unrepentant partier and womanizer—not, perhaps, the perfect recipe for someone contemplating a high-profile public life.

From his parents’ Palm Beach home, Kennedy was enthralled that the Third Reich was being squeezed on all sides. As the Americans and their allies pushed into the heart of western Europe in the months after D-day, the Soviets were closing in on Germany from the east. The war had cost the lives of an astounding twenty-four million Soviet civilians and soldiers, but Joseph Stalin’s government was still standing. On January 12, 1945, the Soviets launched a new offensive that liberated Warsaw and Krakow, captured Budapest on February 13 after a two-month siege, drove the Germans and their Hungarian collaborators out of Hungary in early April, forced the surrender of Slovakia with the capture of Bratislava on April 4, and captured Vienna on April 13. This crystallized the reality to Kennedy that World War II in Europe was almost at an end.

Even though the V-2 never struck a death knell to British morale, Hitler continued to authorize rocket attacks on Britain and Belgium, his two major target nations. Civilian deaths numbered around five thousand but were far short of the massive levels the German High Command had predicted. Many Allied four-engine bomber air raids killed more people in one night than a month of V-2 attacks. Winston Churchill claimed that two people were killed for each V-2 launched against his country—numbers that, while still tragic, were nowhere near enough to change the trajectory of the war, which had tilted decidedly toward Allied victory.

Production of V-2 rockets at Mittelwerk accelerated through January 1945, keeping thousands of slave laborers struggling to stay alive, including Jews diverted from concentration camps to work at the underground factory. The facility was manufacturing almost 700 V-2s per month when production ceased in March. The death rate at Mittelwerk accelerated in the last months of the war due to the collapse of the food supply and increased vicious repression in the Dora camp. And then, on March 27, the last V-2 was launched, killing thirty-four-year-old Ivy Millichamp in the English town of Orpington. All told, the 2,500 V-2s launched by Germany had killed 2,742 people in England and seriously wounded a further 6,467. Casualties in Belgium and France were fairly low. “The V-2’s role in the war was at the end,” historian Christopher Potter wrote in The Earth Gazers, “but its role in history was about to begin a new chapter.”

When U.S. troops crossed the Rhine River at Remagen in March 1945, Hitler issued his Nerobefehl (Nero Decree), ordering the complete destruction of German infrastructure to prevent its use by the invading Allied forces. Human assets, too, were in a precarious position. As German defeat had become inevitable, an emboldened U.S. Army Ordnance Corps used every means at its disposal to identify technical assets within Germany. One of the Army’s aims was to secure the country’s top scientists before they were captured by the Soviets or escaped to the Middle East or South America. Aeronautical engineers, synthetic-fuel experts, naval weaponeers, physicists, chemists, arms manufacturers, and thousands of others were on the list, but none was prioritized higher than the rocket scientist Wernher von Braun.

With Peenemünde bound to be overrun by the Soviet Union, von Braun followed orders by General Kammler to evacuate the facility on February 17. Von Braun helped transport thousands of personnel, equipment, blueprints, and research documents toward the Mittelwerk facility aboard a fleet of trucks, cars, and trains. All were marked with the insignia of the VZBV (Vorhaben zur besonderen Verwendung, or Project for Special Disposition), a nonexistent, allegedly top secret agency they’d invented as a ruse to get the items through SS checkpoints. Reaching Nordhausen, the site of the Mittelwerk factory, the convoy occupied abandoned buildings and began secreting V-2 documents underground. Then, in mid-March, von Braun received orders from General Kammler to evacuate again, with five hundred of his key personnel, to Oberammergau, in the Bavarian Alps.

Monitored by the SS at Oberammergau, von Braun and his rocket team itself became bargaining chips for Kammler, who, using lawyer’s logic, hoped to trade them to the Allies for leniency. If no such bargain seemed possible, he would perhaps look for a deal with the Soviet Union.

Von Braun, however, was the kind of man who, while walking, exuded the feeling of always knowing his destination and how to get there. With the Soviets encircling Berlin on their final offensive and Germany collapsing, he decided that the best option for his team was to surrender to the U.S. Army. “We despise the French,” one member of von Braun’s rocket team later explained. “We are mortally afraid of the Soviets; we do not believe the British can afford us; so that leaves the Americans.” Taking advantage of the chaos and conflicting orders of those final days, von Braun bluffed his way out of confinement. After suffering a broken arm in a car wreck and demanding that it be quickly set in a cast so that he could continue on, he and his team settled at Haus Ingeborg, in Oberjoch, a resort town near the Austrian border. There they rendezvoused with General Dornberger and von Braun’s brother, Magnus, and waited for news. Within days, they learned that Adolf Hitler had committed suicide on April 30 in Berlin, beginning a process that would end a week later with Germany’s unconditional surrender.

With elements of the advancing U.S. Seventh Army only a few miles away, it was decided that Magnus von Braun (who was near fluent in English) would depart to make contact. Climbing on a bicycle, he set off down a country road toward Allgäu. On May 2, in one of those fortunate moments in history, he soon encountered a surprised private, Fred Schneikert of Wisconsin, who aimed an M-1 rifle at him while ordering, “Hands up.” Magnus told Schneikert that the inventor of the V-2 was nearby, ready to surrender. “I think you’re nuts,” Schneikert told him. Nevertheless, Schneikert relayed the message to his U.S. Army superiors.

Enter into the unfolding drama Holger Toftoy, from Illinois, a graduate of the West Point class of 1926 and chief of the U.S. Army technical intelligence teams assigned to Europe to search for, examine, and appraise captured German weapons and equipment. The snatching of von Braun and other Peenemünders was the biggest bonanza imaginable to Toftoy, who was earning a reputation in army circles as “Mr. Missile.” If the army could take custody of V-2 research and parts, then in one fell swoop the United States would soon be the premier rocket-builder in the world. Von Braun’s surrender was the kind of gift horse that Toftoy could only dream about.

Arrangements were made for the Peenemünders to be escorted through the lines that night and held in a safe haven. Following information provided by von Braun and Dornberger, General Toftoy had U.S. Army troops race toward Nordhausen (in what was soon to be the Soviet Occupation Zone) for the spoils of the V-2 program and to Mittlewerk (where the corpses of slave laborers were piled up like cordwood). Having captured the area around Nordhausen and Mittelwerk, Toftoy set up a special V-2-related mission. In one of the great technology grabs in history, U.S. forces collected fourteen tons of blueprints and design drawings from these Nazi facilities and von Braun’s secret mine shaft, and enough parts to fabricate one hundred V-2s. Just days after the U.S. grab, Peenemünde was seized by the Soviets. They confiscated missile hardware and production facilities and the remnants of von Braun’s left-behind production team—but most of the vital personnel, documents, and equipment were already in the American occupation zone. The V-2 materials apprehended in Germany by Toftoy’s team at Nordhausen were shipped by the U.S. Army to Antwerp, and then onward to the United States.

Realizing he was in a technology race with America and was already behind the eight ball, Stalin fumed over being a step behind in the apprehension of Peenemünde technicians, and von Braun in particular. “This is absolutely intolerable,” Stalin pronounced. “We defeated Nazi armies; we occupied Berlin and Peenemünde, but the Americans got the rocket engineers. What could be more revolting and more inexcusable.” This agonized realization came far too late, for the United States had already nabbed the most valuable technology. The Red Army was, however, able to seize research facilities on the island of Usedom, as well as hundreds of executive-level German technicians and engineers. As a further consolation prize, the USSR discovered plenty of machine and rocket components at Mittelwerk. In 1946, the Red Army relocated the captured German assets to the USSR, where the V-2 began a second career as the Soviet R-1.

Safely ensconced with the American forces, von Braun was confident that his team’s priceless ballistic missile know-how would buy them immunity, even though their work had led directly to the deaths of thousands of Allied civilians and ten to twenty thousand prisoners. Undoubtedly the German officers who’d ordered the V-2’s use on civilian populations would be charged with war crimes. Certainly, the soldiers who fired the rockets would be captured and treated as enemy combatants. But the Nazi missilers and mechanical engineers responsible for refining the ballistic rocket technology to kill as many people as possible? For their willingness to surrender and put their knowledge to work for their new American hosts, they would be respected and treasured by the U.S. government (although von Braun got only about 25 percent of the engineers and foreman-level craftsmen he had requested). The double standard was in play. In a dramatic reversal of fate, instead of being treated as war criminals in the months that followed Hitler’s death, von Braun and his team were housed with their families in Landshut, Bavaria, in southern Germany, in a comfortable dormitory complex built for the 1936 Olympics. Von Braun’s team’s alibis were that the tentacles of circumstance had forced them to work for their German Fatherland in wartime. Now, with the Allied victory, they would use their hard-learned rocket engineers’ expertise to help the great United States become a leader in ballistic missile production and, perhaps someday, the only Space Age superpower.

After German surrender in 1945, Charles Lindbergh, working for United Aircraft as a test pilot, was recruited by the U.S. Navy to conduct a study of German rocketry and jet propulsion accomplishments. With a .38 automatic in a shoulder holster and dressed otherwise like a regular GI, Lindbergh explored Germany, stunned at the level of annihilation and decay. Following an intelligence lead, he tracked down Willy Messerschmitt, the designer of the German Messerschmitt warplanes. Messerschmitt saved his postwar hide, as von Braun had with the U.S. Army, by telling Lindbergh all the secrets of Nazi jet propulsion science. What interested Lindbergh the most was the ballistic missile technology of the Third Reich. Working for the navy, he then made his way to Nordhausen to investigate the catacombs where V-2 rockets were constructed in the highest elevation of north Germany, in a rugged mountain terrain. What he saw there, the stunning technology the Germans had developed in the ballistic missile realm, left him flabbergasted. “Imagine,” he recalled, “finding the demon of sheer space hiding in a mountain like a giant grub?”

WITHIN WEEKS OF Germany’s capitulation, the U.S. Army was shipping V-2 rocket parts back home, most eventually making their way via New Orleans to the White Sands Proving Ground in New Mexico. A complete V-2 was confiscated and shipped to the Annapolis Experiment Station for examination, where U.S. government propogandists deemed it quite similar to Goddard’s Roswell rockets. Under Toftoy’s leadership, the U.S. Army was preparing to guide missiles into its postwar weapons program at a rapid pace. In July, at the Potsdam Conference, the Big Three leaders Winston Churchill, Joseph Stalin, and the new American president, Harry Truman—Roosevelt had died of a stroke while in Warm Springs, Georgia, on April 12—disingenuously promised to share all German scientific assets discovered. As historian Walter A. McDougall aptly put it, this so-called agreement “was a sham.”

With the Pacific war still raging, the United States wanted to accelerate America’s missile program, mostly by copying the V-1. Plus, there was no faster route than the wholesale acceptance of the V-2 scientists, parts, components, and complete systems from Peenemünde and Mittelwerk to upgrade America’s long-term missile capability. That June, U.S. troops had conquered Okinawa, the last stop before the Japanese islands. But military leaders knew that sending U.S. troops into Japan itself could easily result in over one hundred thousand casualties. The hope was to bomb Japan into submission.

Von Braun was held at Kransberg Castle for a couple of days, which under the code name “Dustbin” served as an Anglo-American detention center for German scientists, doctors, and industrialists. The interrogation that was integral to his intake process went well. On July 20, 1945, U.S. secretary of state Cordell Hull green-lighted the transfer of all German technology experts as part of a secret recruitment program that had been named Operation Overcast. Initially, von Braun fretted that he and his team would be squeezed for information, perhaps bullied, and then shipped back to West Germany to stand trial for war crimes, but he needn’t have worried. With the war in the Pacific still raging and competition with the Soviets already heating up, the rocket engineers were given protected status by Toftoy. Working clandestinely, the Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA) classified the records of German “Peenemünders,” as they were dubbed, expunging any evidence of Nazi Party membership that might pose a security threat. With this whitewashing complete, the German rocket engineers, physicists, chemists, and others were provided security clearances to work in America, inoculated against prosecution for war crimes.

In full cooperation with Toftoy, von Braun’s team exhaustively explained the captured V-2s to their new American colleagues, rebuilt the rockets, and commented on current missile-related projects not yet actualized. With the same sureness of touch, von Braun even began campaigning for the financial resources needed to make more advancements. His sharp and level pitch was convincing: in just a few years, the V-2 would be considered last year’s military hardware, replaced by warheads one hundred times more lethal. What surprised the U.S. interrogators most was von Braun’s determination to fire V-2s beyond the “top layer of the atmosphere”—that is, into space. To his interrogators, von Braun praised the pioneering work of Dr. Robert Goddard, who had died on August 10, 1945, in Baltimore, after a battle with throat cancer. Over the years, von Braun gave several accounts of Goddard’s influence on the V-2, indicating that it had been minimal. His abundantly generous comments in 1945, however, marked an almost symbolic turning point for American rocketry. Once Goddard was buried in Worcester, Massachusetts, leadership in the field of rocket engineering fell to the newcomers who had surpassed him. In a calculated ploy, von Braun, facile at scheming and maneuvering to promote his work, had nothing to lose and everything to gain by citing Goddard so extravagantly.

In November 1945, Operation Overcast was renamed Operation Paperclip by JIOA for security breach reasons. The name was chosen by officers who would fasten a paper clip to the folders of Nazi rocket experts they chose to hire. In its first year, 119 German rocket engineers were brought to the United States, cleared of war crimes, and put to work under Operation Paperclip. While von Braun and the others were assigned to work at forlorn Fort Bliss, near El Paso, Texas, Toftoy himself directed the army’s new guided missile program from an office in Washington, DC.

IN THE ENTIRE twentieth century, the splitting of the atom during World War II would prove to be the only human event on a par with the American moonshot. The Atomic Age was born on July 16, 1945, when the Trinity Test was successful in New Mexico. What this meant to human civilization became abundantly clear on August 6, 1945, when the Enola Gay dropped the first atomic bomb, “Little Boy,” on the city of Hiroshima, Japan. Within four months, the acute effects of the atomic bombing had killed somewhere between 90,000 and 146,000 people in Hiroshima, and 39,000 and 80,000 people in Nagasaki, where a second bomb, nicknamed “Fat Man,” was dropped three days later; about half the deaths in each city occurred during the first twenty-four hours. There was nothing iffy about the total annihilation of these cities; each was turned into a smoking wasteland of rubble. Confronted with the possibility of total destruction of their nation, the Japanese surrendered on August 14, 1945. (The formal surrender ceremony was held aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2.) While most Americans cheered, relieved that U.S. armed forces had been spared a bloody invasion of the Japanese homeland, the reality began to sink in that humanity had entered a dangerous new epoch. “Dropping the bombs ended the war,” President Truman later boasted, “saved lives and gave the free nations a chance to face the facts.”

Created in Los Alamos, New Mexico, hours northwest of Goddard’s Roswell ranch, the atomic bomb ushered in an age in which humans held the godlike power to end life on Earth. The potential combination of the bomb with the new forms of ballistic missile technology conceived by von Braun meant the end could come without warning, at any time. Ironically, Germany’s V-2 program had been partially spurred by unreasonable fears of American rocket development—U.S. rocketry was then effectively nonexistent—while America’s conviction that Germany would soon invent an atomic bomb had spawned the Manhattan Project, which produced the bombs used on Japan. (In fact, Germany canceled its atomic program long before conceiving a viable weapon.) Significant though the Soviet breakthroughs in military aviation had been, after World War II, the United States held a virtual monopoly on both V-2 rocket and atomic bomb technologies.

The atomic bomb instantly transformed the nature of warfare and rendered all previous strategy moot. Armies didn’t have to roll down the street with tanks to conquer. War no longer had to mean the rumble of diesel engines or the thunder of big guns in the distance. Because it could not be defeated by conventional forces, the American superweapon became a new source of fear and dread to the Soviets. Some thought America’s monopoly over the atom gave it the leverage to obtain a postwar settlement largely on its own terms. Others knew that the Soviets, whose decisive victory over the Nazis had just won them the first real security they’d enjoyed since 1917, would never accept U.S. hegemony.

The atom bomb also made individuals think differently about their own lives. Global citizens could no longer feel fully safe in their own homes. Rockets didn’t offer parents time to run and save their children. Any given second could be the last. Ominous portents were self-evident. “A screaming comes across the sky,” novelist Thomas Pynchon wrote decades later in Gravity’s Rainbow. “It has happened before, but there is nothing to compare it to now.”

ACCORDING TO THE U.S. federal government’s own estimate, at the close of the war, America had been eight years behind the Germans in rocket capability. With the arrival on American soil of von Braun and the other Peenemünde engineers, that gap vanished all at once.

Meanwhile, in late 1945, von Braun and his rocket team were assigned work contracts with the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps, which was interested in developing rockets and artificial satellites out of the public glare. They were officially called “War Department Special Employees.” For the next five years, these German scientists, stationed at Fort Bliss, Texas, near El Paso, were engaged mainly in rebuilding captured V-2 rockets, which would then be sent to the army’s White Sands Proving Ground in nearby New Mexico, where army and navy personnel and technicians from General Electric would conduct tests designed to improve the rockets’ destructive capacity. New Mexico had already had a world-altering role as the site of the first-ever atomic bomb test, on July 16, 1945; now this isolated White Sands tract of land the size of the state of Connecticut was populated by scientists, pilots, and engineers, its beautiful arid landscape dotted with spider-like antennas, cargo trucks, watchtowers, and optical telescope laboratories. Federal purse strings had been loosened for rocket construction in the region.

At first the status of the German rocket engineers at Fort Bliss was murky. Considered wards of the army, the men in the von Braun team had no passports or visas, their mail was censored, and they weren’t allowed off the Fort Bliss base without an escort. But their families were allowed to join them from Germany, which was a real boon. These engineers weren’t exactly prisoners: they could return to Germany, if they insisted, though they couldn’t move anywhere else in the United States. Von Braun himself was well paid for his work by the federal government, earning an annual salary of six thousand dollars—more than twice the average American income of the era.

Although exasperated by their limbo, few on von Braun’s team opted to leave El Paso during those first years. Located across from Juarez, Mexico, on the northern side of the Rio Grande, the city offered a better, more secure lifestyle than a now-divided Germany, especially for a valuable scientist. In El Paso, the expatriate scientists occupied their nonworking hours hiking the Franklin Mountains (with escorts), watching local football games, going to movies, and learning English. Von Braun dubbed himself a POP (prisoner of peace) rather than a POW, and he nurtured his genuine interest in local history by talking with cowboys and drifters about the curve of the Big Dipper and the non-visible four points of the Southern Cross at local gatherings. At Fort Bliss, he said, “The GIs sized me up with uncomfortable accuracy,” referring to his German accent. “But they also invited me to join their black jack and poker games.”

Though isolated and confined, the Germans at Fort Bliss knew they’d been lucky to escape what could have been much worse fates after the war’s end. While they were comfortably under contract in Texas, rocket engineers in Russian-occupied East Germany faced the real prospect of being kidnapped and sent to the USSR under house arrest. Ultimately, the Soviets would appropriate four thousand German rocket engineers, along with several complete V-2 assembly lines. At the same time, many old colleagues from the Third Reich’s scientific and industrial hierarchy were standing trial in Nuremberg for war crimes. Thousands of other Germans were under scrupulous investigation as part of the Allies’ denazification process.

Von Braun and his scientists had also been denazified, but in a more clandestine way, having had their security ratings changed by the U.S. Army intelligence to make them acceptable emigrants. Any nostalgia for their German homeland—the dark forests, beer halls, and autobahns—had been subordinated by a newfound love of American democratic institutions by most. But some of the imported Germans were sent back home, labeled as “ardent Nazis,” unfit for U.S. residency. Others left voluntarily. Those that stayed, deemed not “ardent Nazis,” were the ones the Army wanted to keep.

Arthur Rudolph, a close colleague of von Braun and chief operations officer at the Mittelwerk V-2 production facility, where he oversaw the slave labor, was an ardent Nazi and anti-Semite. Nevertheless, he was quietly accepted into the United States and granted citizenship in the mid-1950s. Keeping a low profile at Fort Bliss, working in secrecy, he immediately began making contributions to the American rocket program, as did ex-Peenemünder Kurt Debus. Hubertus Strughold, another beneficiary of Operation Paperclip, was a physician who had been the director of the Luftwaffe Institute of Aviation Medicine during the Nazi era. In the United States, he was given a similar job, heading the new Air Force School of Aviation Medicine, in West Texas. Even as Strughold was settling in America, quite at liberty to enjoy the privileges of democracy, his former colleagues were facing trial at Nuremberg for war crimes he’d known about. In one experiment, Jewish inmates from concentration camps had been forced to squat in a chamber as the pressure inside the chamber was altered in a matter of seconds, simulating a depressurized airplane dropping from high altitude. The doctors watched as the prisoners died or permanently lost their minds.

The first successful V-2 launch in New Mexico occurred in May 1946, the rocket soaring to an altitude of sixty-seven miles; it was deemed a failure. Over the next five years, about seventy V-2 tests were conducted at White Sands, two-thirds of them successfully. Barely a day went by when von Braun wasn’t daydreaming about Mars and the moon. During the early Cold War, he managed to design his first trajectories for a potential flight to the moon and started hunting for funding allies in Washington. Work associates knew that when von Braun got a faraway gleam in his eyes, he was daydreaming about a lunar voyage, bringing his imagination to bear on the thousands of necessary steps.

Nevertheless, the conundrum that had existed since the 1920s still haunted rocket engineers: long-range rockets were ideally suited to be used as weapons. With World War II over and geopolitical competition with the USSR already under way, interest and investment in rocketry as a military asset surged, while interest in and funding for peaceful applications such as manned space exploration and satellite telecommunications continued to lag. Attempting to alter this vast imbalance, Lieutenant General Ira Eaker, deputy commander of the Army Air Force, wrote the War Department in May 1946 requesting budget support for dozens of top secret test launches. The plan was to use modified and unmanned V-2s in what he described specifically as a “scientific endeavor” to explore space for peace. In truth, these V-2 tests were aimed at providing the United States with guided missile technology, deemed essential to deter the Soviet Union from overplaying its postwar hand in Europe. But massive U.S. budget cuts of 1946–48 ended many potential missile projects.

Eaker, the son of tenant farmers in Texas, had become a single-engine pilot during World War I and in 1930 made history by piloting the first transcontinental flight using in-flight refueling. A serious writer on military aviation, he coauthored the highly respected This Flying Game (1936), Winged Warfare (1939), and Army Flyer (1942). While Eaker was commanding the American air effort in Europe during World War II, he improved the strategy of precision daylight bombing, which allowed for round-the-clock attacks against the enemy. Even though he was known mainly as a hardened, no-nonsense commander of bomber groups, his 1946 proposal to the War Department saw a moon voyage as a practical measure concomitant with the United States leading the world in space technology, although he admitted it was a largely unknown field. “If we may assume that the future of air conquest will bring with it a conquering of outer space,” he wrote, “then clearly this experience and the enthusiasm which this project will generate will be very beneficial in the long run.” Apparently the feeling in Washington was that the proposal was a highly fungible waste of money; space wasn’t going to be the next domain of airpower.

AROUND THE TIME von Braun’s group surrendered to the U.S. Army, Jack Kennedy was in San Francisco, reporting for the Hearst syndicate on a conference called to negotiate the charter of the new United Nations, an organization designed to foster global peace and cooperation. When he returned east, his father arranged for him to spend the summer touring war-ravaged Germany with fellow Irish American James Forrestal, President Truman’s navy secretary. It was apparent to Kennedy that London was pummeled, Paris disgraced, Rome tarnished—the old European capitals he had visited with Lem Billings before World War II were dysfunctional compared with cosmopolitan San Francisco and New York City. Somewhat paternally, Forrestal tutored Kennedy on the postwar national security imperatives facing the United States and how the decisions of the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference held in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in 1944 guaranteed that the U.S. dollar would be the reserve currency of the postwar world.

Meanwhile, Joseph Sr. commissioned a lecture bureau to schedule speaking engagements for Jack, met with local Massachusetts politicians to lay the groundwork for his son’s future, and hired a team of political veterans to organize a congressional campaign in Massachusetts’s Eleventh District (which included Cambridge, the home of Harvard University). In early 1946, Jack publicly announced his run for the seat. He wasn’t experienced in retail politics and he wasn’t local, either, but he quickly took up residence in the heavily Republican district to begin his run as an anticommunist liberal. According to Joseph Kennedy biographer David Nasaw, the patriarch acted as Jack’s behind-the-scenes campaign manager, marketing him as a “fresh-faced, charming young war hero, with a bit of glamour and a wholesome down-to-earth quality, a Harvard man and a man of the people, a book-writing intellectual who was everyone’s friend.”

The Kennedy family formed a devoted juggernaut on the front lines of the 1946 campaign, and Jack reciprocated by giving it his all. He didn’t want to let his siblings down, and he knew the campaign was his audition for a run for higher office down the line. Some people were already touting him for the Massachusetts governorship, the position that had long eluded his maternal grandfather, John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, the popular two-term Boston mayor.

And yet, Jack knew that he wasn’t the typical Bay State politician. On paper, he had little in common with a predominantly working-class electorate in factory cities of the Eleventh District, people who were eking out a low-paid livelihood. He was also a practicing Roman Catholic (which was not necessarily an asset), he wasn’t married, and he didn’t belong to any local clubs or civic groups in his district. Hair tousled and clothes casual, Kennedy was also a private man, preferring to keep to himself or pass the time with his best friends. Pandering to voters wasn’t really in his makeup. With smiling ease, he could be full of good conversation while never completely connecting with anyone or revealing a thing. Nevertheless, during the course of the 1946 campaign, a persona was forged at the overlap between JFK’s authentic self and the fresh-faced leader for whom voters hungered. Having rushed headlong into politics, he milked his sardonic charm, terrific drive, unforgettable smile, and unique sense of irony that connected him to a wide range of idiosyncratic audiences through laughter.

Self-assured and pleasant, Kennedy clung to his abiding sense of intellectual aspiration, resisting the politician’s instinct to dumb down his rhetoric for a broader audience. Amid the well-worn traditions of Boston’s Democratic circles, Jack was in danger of being deemed professorial. On this first campaign, he honed his meet-and-greet skills, but avoided pandering. “It was said,” marveled Tip O’Neill, who later represented the Eleventh District, “that Jack Kennedy was the only pol in Boston who never went to a wake unless he had known the deceased. He played by his own rules.”

On the campaign trail, Jack was full of intoxicating kick-and-go. Recognizing that politics was a learning process, he spent long days canvassing for votes throughout the district, leaving himself only six hours a night for sleep. While his father lavished the campaign with more money than all the other candidates combined, and used his influence, high and low, in every conceivable way, Jack was proving his mettle in face-to-face interactions. The spoiled scion, as it turned out, was a sincere candidate with something fresh and cogent to say about postwar America. What Kennedy understood was that the economy was the most overwhelming concern for voters. On a theoretical level, citizens wondered whether the Great Depression would grimly pick up again where it had left off before wartime industrialization. On the more practical level of daily life, people struggled with shortages of housing, food, and other basic necessities, and worried that events such as the massive labor union strikes occurring that year could unravel the fragile postwar economy.

Two other issues, lying just under the surface of the race in 1946, were the performance of President Truman and the direction of the Democratic Party itself. A year after the death of Franklin Roosevelt elevated him to the presidency, Truman seemed a dreary placeholder compared with his dynamic predecessor. The man who had made the epochal decision to drop atomic bombs on Japan the previous August was now largely perceived as an ineffective leader, with an approval rating of only 37 percent. Beyond the presidency, the entire Democratic Party was having difficulty defining itself after the nearly thirteen-year Roosevelt presidency. Taking a dim view of Truman’s inability to excite the public and his uneven defense of labor, many Democrats glumly accepted in 1946 that the spirit of the New Deal was over, while others clung to its promise. After going so far as to tell the president to remain on the sidelines in these midterm elections, Democratic Party leaders distributed radio spots to congressional candidates featuring voice clips of the late FDR, tacitly admitting that their past still overshadowed their present. While Democrats scrambled for some kind of new governing vision, the Republicans grasped the upper hand by embracing a staunchly anti-Soviet, anticommunist posture that became the defining issue of the times.

It was the beginning of the decades-long geopolitical Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. After their joint victory in World War II, festering distrust coalesced quickly into opposition. In March 1946, with the Soviets consolidating their control over Eastern Europe, Winston Churchill delivered a speech in which he declared, “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the continent.” Stalin was the new Hitler, in this view, willing to purge his own citizens, bent on expansionism and the creation of a Communist world order. Holding back the tide would require a unified West and the continuing presence of American military might in Western Europe.

Among many Americans, including Kennedy, suspicion of the Kremlin metamorphosed into a creeping paranoia, igniting a Red Scare against alleged Communist infiltrators at many levels of American society. The furor swept up both voters who were rightly concerned about the Soviet threat and those who were easily led by their fears. The murkiness of the line between reason and hysteria and the whisking away of serious deliberation bothered many old New Deal Democrats. But any liberal candidates who attempted a nuanced discussion were attacked as being soft on communism. It seems incredible in retrospect that in 1943, Stalin had been Time’s “Man of the Year,” an ally against Hitler, but a few years later he was rightfully vilified in the United States and elsewhere.

As for the new Democratic congressional candidates of 1946, Jack Kennedy was uniquely prepared for the Red Scare, having lived under the same roof as one of its earliest anticommunist mouthpieces, Joseph Kennedy Sr. A rock-ribbed political pragmatist, Jack unabashedly supported containment of the Soviet Union and a strong arm against domestic Communists. He was willing to stand up to big labor and steer clear of alliances with groups that might define (or, worse, constrain) his ambition. Unleashing his inner Churchill, Kennedy lashed out at everything from the gulag concentration camps in Siberia to the Kremlin’s repression of journalists. In October, he gave a speech to the Young Democrats of New York, scolding Henry Wallace, the former vice president and recently dismissed secretary of commerce, for espousing pro-Soviet views. Later, in a Boston radio broadcast, he recounted what he had told the group about Soviet totalitarianism. “I told them that Soviet Russia today is a slave state of the worst sort,” he recounted. “I told them that Soviet Russia is embarked upon a program of world aggression. I told them that the freedom-loving countries of the world must stop Soviet Russia now, or be destroyed. I told them that the iron curtain policy and complete suppression of news with respect to Russia, has left the world with a totally false impression of what was going on inside Soviet Russia today.”

Choosing to distance himself from Truman, Kennedy epitomized the new liberalism that historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. yearned to see in the postwar atmosphere. Schlesinger, who had been in Joe Jr.’s class at Harvard, was within six months of Jack’s age. Having won literary praise for his 1945 history The Age of Jackson, he was back at Harvard as a teacher when he began thinking about his next book, a study of liberalism in the modern era. Schlesinger wasn’t pondering Kennedy when he wrote The Vital Center, but the iconoclastic young Democrat fit the bill. In the first place, he was not an obsessive New Dealer. Schlesinger had no patience with those hanging on to the old era. Having come to reject the idea that humans could be perfected if they received enough government help and kindness, he realized that they could, through an equal and opposite reaction, be cowed into subservience by dictators. To form a bulwark against extremism, Schlesinger called for a tough new liberalism that would extend civil rights but give no truck to totalitarians, whether fascists on the right or Communists on the left.

Yet there was a pivotal difference between Kennedy and others (notably Richard Nixon, then a candidate for Congress in California) who were tough on communism, and an even bigger difference with the political philosophy Schlesinger was then formulating. Even as he consolidated his staunch anti-Soviet views, Kennedy retained his bright-eyed idealism. A romantic at heart, he believed, like Thomas Jefferson, in human beings’ inherent perfectibility, and he brought the priority of peace to every discussion of foreign affairs.

As one of the youngest candidates running for federal office in 1946, Jack Kennedy offered something other than life experience. Instead, the war hero presented himself as a reflection of his times. The fight against fascism had shaped Kennedy and his generation, forging in them a fortitude and resilience no parental wisdom, no college education, no career experience ever could have. “The war made us get serious for the first time in our lives,” he said. “We’ve been serious ever since, and we show no signs of stopping.” He also knew that the dawn of the Atomic Age had amplified that seriousness in a way no previous generation had ever had to face. In coming years, the United States would conduct more than a thousand nuclear tests, in the Pacific Ocean on Amchitka Island, in Alaska, in Colorado, Mississippi, Nevada, and New Mexico. “What we do now will shape the history of civilization for many years to come,” he said in his first major speech. “We have a weary world trying to bind up the wounds of a fierce struggle. That is dire enough. What is infinitely far worse is that we have a world which has unleashed the terrible powers of atomic energy. We have a world capable of destroying itself.”

That November 5, 1946, at age twenty-nine, Jack Kennedy was elected as the U.S. representative for the Eleventh Congressional District near Boston. The Democrats that year mustered only 188 seats. Out in California, navy veteran Richard Nixon was swept into Congress on a Republican wave, along with 245 other members of the GOP.

JACK KENNEDY’S PUBLIC career was born amid the postwar reality of atomic bombs, ballistic missiles, and the still-unrealized threat of intercontinental long-range rockets. He favored an international body to oversee atomic weapons, largely as a way of maintaining America’s monopoly by dissuading other nations from building their own nuclear arsenals. But as far as Kennedy and most other politicians were concerned, rockets were simultaneously the V-2 past and the Flash Gordon future. In a country trying to regain a sense of normalcy, it seemed that the only group really focused on rocketry was the military, including the U.S. Air Force, a new division of the armed forces that had been established in the fall of 1947 via the National Security Act. Like the Army, this branch had benefited from having sponsored hundreds of Paperclip scientists and engineers. The Air Force was keenly interested in the Luftwaffe’s technology pertaining to transsonic and supersonic aerodynamic research.

The previous autumn, Wernher von Braun had made his first public speech in America, to the El Paso Rotary Club. “It seems to be a law of nature that all novel technical inventions that have a future for civilian use start out as weapons,” he said, before going on to predict a future where rocketry took its proper role of propelling satellites and space stations into orbit and enabling missions to the moon and beyond. Von Braun got a thundering ovation and was cheered by the support, but as usual, his ideas were ahead of their time. Before his space dreams could take flight, rocketry would enter new and even more dangerous territory with the postwar development of the first intercontinental ballistic missiles.

The only sensible thing for von Braun to do was, once again, to lie low and develop his ballistic missiles in Fort Bliss–White Sands for U.S. Army purposes while keeping a moon and Mars voyage as a long-term interior motive. In 1946, the Army Signal Corps succeeded in bouncing radio waves off the moon and received the reflected signals back on Earth. This was a stunning achievement, for it established that radio transmissions through space and back to Earth were possible. This public discovery didn’t mean anything to Kennedy, running for Congress. But to von Braun, it was proof that such signals could in the very near future be adapted to control manned and unmanned spacecraft alike.