The notion of a “race” with the Soviet Union permeated Cold War thought, and it applied not only to space but to nuclear arms.

—YANEK MIECZKOWSKI, EISENHOWER’S SPUTNIK MOMENT (2013)

As John F. Kennedy started his congressional career in early 1947, the Cold War was on, full bore, with the United States and the Soviet Union shoring up their influence in a divided Europe. In following years, advanced intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and high-altitude reconnaissance plane innovations would forever change the notion of warfare. Having read so many history books, Kennedy prided himself on being able to make quick summaries of pressing global situations and offer pragmatic recommendations. JFK relied on the power of family ties, trust fund, and personal freedom—he was an island unto himself, questing for the present moment.

For Jack, 1947 was a year of both visibility and irrelevance. An eligible bachelor and nightclub habitué, and possessed with a mercurial attractiveness, he moved into a town house on N Street, in Washington’s Georgetown neighborhood. He cut a dashing figure as one of the youngest lawmakers in town, balancing a social life in the fast lane with a minor reputation for occasional eloquence on the House floor. Still, Kennedy was often bored during his first term, full of indifference, realizing quickly that a low-ranking member of the minority party had little of importance to do on Capitol Hill. Perhaps in response, he traveled frequently, not only back to New England but also around the country, speaking to almost any group that would invite him.

In official Washington, dollars and cents ruled the agenda. Having spent a third of a trillion dollars on the war, the federal government had war bonds to repay, both as an obligation and also in the interest of fueling the postwar economy. Another pressing expense was financial assistance to nations devastated during the war. Speaking at Harvard on June 5, 1947, Secretary of State George Marshall presented the outline of a plan that would “help the Europeans help themselves” by pumping more than $13 billion (almost $150 billion in 2019 dollars) into rebuilding war-ravaged Western Europe: stabilizing currencies, budgets, and finances; promoting industrial, agricultural, and cultural production; and facilitating and stimulating international trade relationships. In occupied Japan, a similar program under General Douglas MacArthur was beginning its work of rebuilding the war-ravaged island nation along capitalist lines.

Most Americans believed that the Soviet Union, having lost more than twenty million lives in World War II, must also be focused completely on the task of infrastructure rebuilding—a casual assumption that played to the Soviets’ advantage in missile and nuclear bomb development. Because the Kremlin maintained what science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke called “an almost impenetrable veil of secrecy,” U.S. intelligence services had little idea how rapidly the Soviets were in fact developing their capacity in nuclear weaponry and advanced rocketry. After World War II, Sergei Korolev, principal designer of the future Soviet space program, had been tasked by Stalin to build powerful ICBMs. Initiating a systematic exploitation of German guided missile technology, by 1946 they were already working on ballistic missiles with a range of nearly two thousand miles. Within fifteen years, they would make technological leaps that would lead to the first nuclear-tipped ICBMs and would also propel Russian cosmonauts toward space. Soviet engineer Mikhail Ryazansky also spearheaded a cabal of scientific specialists who pioneered new radar and radio navigation technology. As the Kremlin innovated a large-scale missile program, the United States, von Braun rightfully complained between 1945 and 1951, had “no ballistic missiles worth mentioning.”

While the Soviets built, the U.S. military engaged in squabbles fueled by an interservice rivalry. With budgets down from their stratospheric wartime levels, the various armed services jockeyed for every congressional appropriation and threw elbows while they did. The new National Security Act also threatened their autonomy, placing the army, navy, and marines under the authority of a new National Military Establishment (later, the Department of Defense) and separating the U.S. Army Air Forces (AAF) out into its own service, the U.S. Air Force (USAF). Amid these budgetary and administrative struggles, the development of rockets chugged along slowly on multiple tracks across the armed forces as engineers explored their potential as weapons, research tools, launch vehicles for satellites, and vehicles for space exploration.

In the air force, Major General Curtis LeMay, a war hero then serving as deputy chief of air staff for research and development, believed that any future space program should be under the domain of air operations. Born in 1906 in Columbus, Ohio, LeMay had commanded the 305th Operations Group and the Third Air Division in the European Theater during World War II. A dashing fighter pilot able to loop and dive with the best, he ran strategic bombing operations against Japan toward the end of the war. After V-J Day, LeMay was assigned to command the U.S. Air Force in Europe and to deal with the nonstop crisis in Berlin, which was then divided among American, British, French, and Soviet zones of occupation. LeMay commissioned the research-and-development arm of Douglas Aircraft, in Southern California, to answer two fundamental postwar questions: How could satellites benefit the U.S. military? How could space travel advance humanity? He gave the aerospace corporation three weeks to report back.

Douglas Aircraft’s RAND unit (which took its name from a contraction of the term research and development) had been created immediately following World War II, by a number of military and industry leaders, including General H. H. “Hap” Arnold, who’d served as head of the U.S. Army Air Forces until 1945. Arnold understood that military science was accelerating at a mind-boggling rate, one that would affect all the service branches, but aviation in particular. His insistence that academia, industry, and the military had common goals and would benefit from cooperation was revolutionary during the transition from war to peace, paving the way for decades of expansion in all three sectors.

The 321-page Douglas Aircraft RAND report was delivered on May 2, 1946. Titled Preliminary Design of an Experimental World-Circling Spaceship, this document described future military uses for Earth-orbiting artificial satellites, including surveillance and missile guidance. It suggested a raft of civilian possibilities, too, notably in communications and meteorology. The RAND report, the work of fifty researchers, presented two conclusions that offered infinite potential for the air force. First, a satellite vehicle with appropriate instrumentation would become one of the most revolutionary military, scientific, and communication tools in the twentieth century. Second, this type of satellite could inflame the aspirations of mankind. “Whose imagination is not fired by the possibility of voyaging out beyond the limits of our earth, traveling to the Moon, to Venus and Mars?” the report asked. “Such thoughts when put on paper now seem like idle fancy. But, a manmade satellite, circling our globe beyond the limits of the atmosphere is the first step. The other necessary steps would surely follow in rapid succession. Who would be so bold as to say that this might not come within our time?”

The various RAND findings were discussed in detail at a top-secret conference called to consider the idea of uniting the navy and air force in satellite development. The cost of launching a satellite was estimated at around $150 million and to be ready by 1951. Representatives of the two branches, however, couldn’t agree, and military officials looking for a compromise soon lost interest. The RAND study was filed away.

Turning away from the RAND satellite recommendations, the navy used its prerogative in late 1946 to order the development of a rocket ultimately named the Viking. Created by Baltimore’s Glenn L. Martin Company (later part of Lockheed Martin) in conjunction with the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, the Viking was built on the basis of the V-2 but was a distinctly American effort, even incorporating some ideas by the late Robert Goddard. “The U.S. Navy wanted no part of the haughty Germans, no matter how talented they were,” wrote historian and NASA veteran Doran Baker. The Viking was developed principally to gather upper atmospheric and ionospheric data that would help predict weather and would communicate via satellites. It would prove a huge boon to America’s military and commercial aviation industries in coming decades. At the White Sands Proving Ground in New Mexico, test launches of the Viking were able to carry research instruments to altitudes of up to 158 miles.

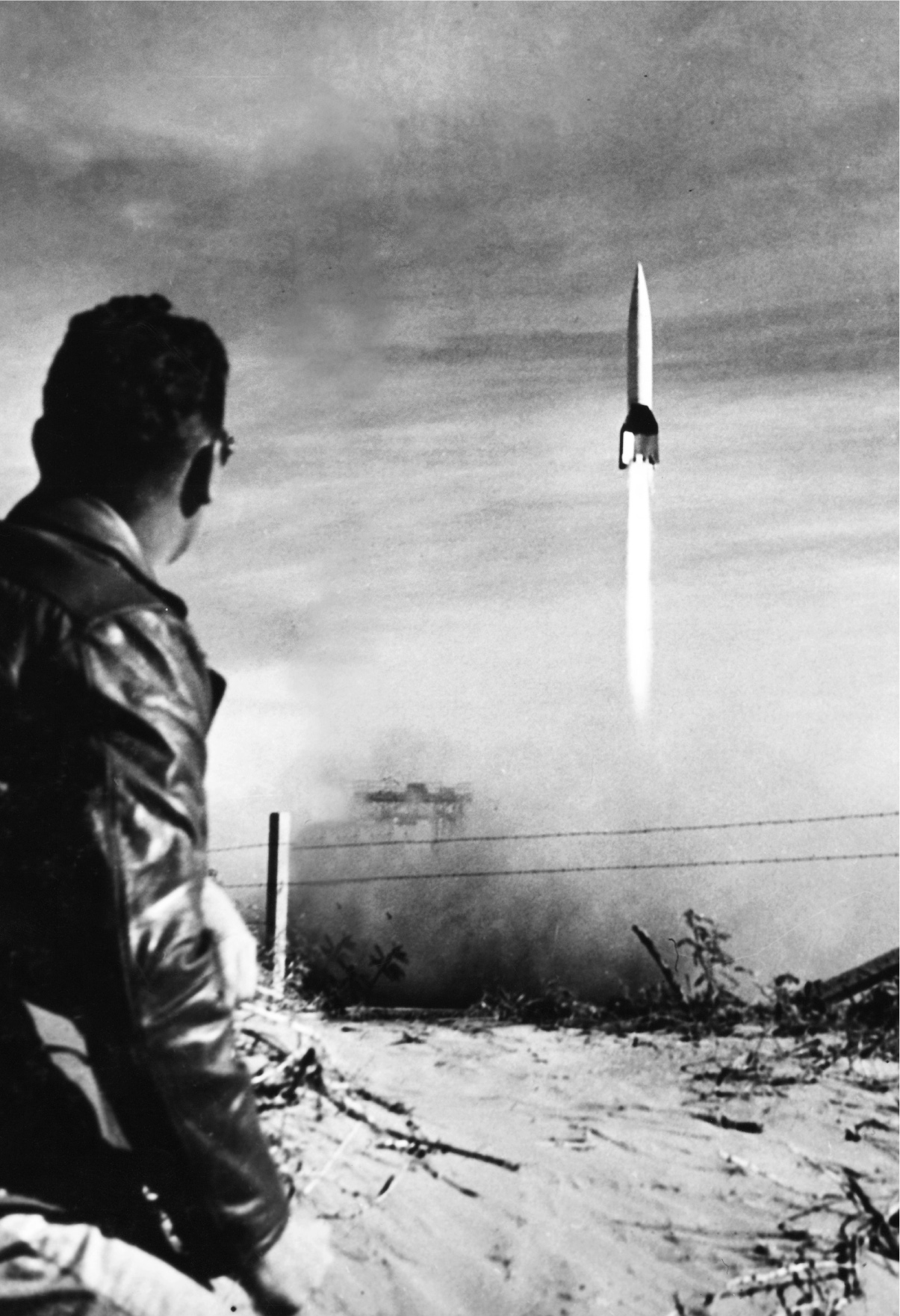

A captured German V-2 rocket just after takeoff at Launching Complex 33 at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. The launch was part of an experimental program carried out by the U.S. Army’s Upper Atmosphere Research Panel.

Schenectady Museum; Hall of Electrical History Foundation/CORBIS/Getty Images

The U.S. Army was continuing its own missile work, relying heavily on German technology and expertise from Fort Bliss. When the Dora-Mittelbau war crimes trial ensued in 1947 at Dachau, the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps made it clear that the von Braun team (the Peenemünders) had eluded any charges. Unscathed by the Dachau trial, in the fall of 1948 von Braun’s team began contemplating the development of Earth-orbiting satellites. The Committee on Guided Missiles requested that von Braun’s Fort Bliss–White Sands desert team design a way for the army to pioneer the science of satellite carrier-rocket development. Shortly after Christmas, James Forrestal, now the first “secretary of defense,” publicly declared that the Pentagon was looking into the workability of artificial satellites. This was just a preliminary launching by the U.S. government looking into Earth satellite vehicles. Documents from 1949 show that the RAND Corporation had convinced the Pentagon of the satellite’s potential for surveillance, reconnaissance, communications, and intimidation, suggesting that the “mere presence in the sky of an artificial satellite would have a strong psychological effect on the potential enemy.”

While many researchers in El Paso, Pasadena, Hampton, and at air force bases such as Edwards, Wright-Patterson, and Kirtland were looking to space as the next frontier, others were making history within Earth’s atmosphere. On October 14, 1947, a West Virginia test pilot named Chuck Yeager, a master of aerial evasion and dive-bombing, strapped in for a test flight of the Bell X-1 experimental aircraft, nicknamed Glamorous Glennis, after his wife. Launched from the bomb bay of a Boeing B-29 Superfortress over the Rogers Dry Lake in California’s Mojave Desert, Yeager’s X-1 reached an altitude of 43,000 feet and a speed of 700 miles per hour, marking the first time a plane had exceeded the speed of sound in level flight.

Following World War II, the United States went aviation crazy. Even though mass transportation was still the domain of ships, trains, and automobiles, commercial airlines such as Eastern were making inroads with passenger cabins designed for comfort. Cities started building airplane terminals with bonds to be paid out in thirty or forty years. With a plethora of trained pilots, commercial aviation routes were established almost like the old pioneer routes of the nineteenth century’s era of westward expansion. During Truman’s presidency two reliable routes were opened for transcontinental air travel: the New York–Chicago–San Francisco route in the north and the New York–St. Louis–Los Angeles route to the south. Electronic navigation and anti-icing technology, both developed during the war, soon allowed for all-weather flying, though fog and snow caused groundings. Despite subpar safety standards, every year, more and more Americans were using commercial aviation as their preferred mode of long-distance travel. Still, too often local newspapers ran horrific stories of wings falling off, midair collisions, and crashes on landing. Aviation technology would have to improve before air travel was truly embraced with mass appeal.

ON JUNE 24, 1948, long-simmering tensions in divided Berlin came to a boil when Stalin ordered the closure of all land routes to the parts of the city controlled by American, British, and French forces. It was a power play aimed at starving out the Western powers and forcing them to abandon Berlin, located 110 miles within what was the Soviet zone of postwar German occupation, an area soon to become the German Democratic Republic. But the maneuver didn’t work. From June 28 to May 11, 1949, the three nations launched the Berlin Airlift, a massive effort that successfully supplied the citizens of Berlin with food, fuel, and medicine. The U.S. Air Force, which continued flying supplies until 1949, scored a major humanitarian triumph with the dropping of foodstuffs and medical provisions, as more than two hundred thousand sorties carried in over 1.5 million tons of supplies to the surrounded city.

The successful U.S. airlift helped Truman defeat his Republican challenger, Thomas Dewey of New York, in November’s presidential election, surprising pundits. Kennedy was also reelected, and enough other Democrats took formerly Republican seats to regain control of the House of Representatives. Two years into his political career, JFK had proved surprisingly businesslike in the job, with his congressional offices in Washington and Boston having a reputation for crackerjack staff and unassailable constituent service. He also proved to be a bright, solicitous colleague and was well liked on Capitol Hill. Nobody thought he was a workhorse. But he was his own man, a stand-alone, never part of a faction or clique. Although he usually voted with fellow Democrats, he made no effort to curry favor with such power brokers as Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn or Majority Leader John McCormack—something that was unheard of for a junior representative. It was as if Kennedy’s good looks, great wealth, and war-hero status allowed him the privilege of being an island unto himself on Capitol Hill. Speaking frankly, Rayburn called Kennedy “a good boy” but “one of the laziest men I ever talked to.”

On the other side of the Capitol Building, in the upper chamber, another New Englander recently arrived on the Hill had chosen a different way of making a name for himself. Even before the U.S. nuclear attack on Hiroshima in 1945, the forward-thinking Connecticut senator Brien McMahon had adopted atomic technology as his area of expertise in Congress. In the years after the war, he deemed the July 1945 test detonation of the first atomic bomb in New Mexico “the most important thing in history since the birth of Jesus Christ.” After V-J Day, McMahon believed the United States had a vested national security interest in remaining the world’s only atomic superpower. Serving as chair of the Senate Special Committee on Atomic Energy, McMahon became known for the rest of his congressional career as “Mr. Atom Bomb” for his authorship of the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, which created the Atomic Energy Commission to control nuclear weapons development and nuclear power management, stripping this authority from the military. At the same time, McMahon concerned himself with the geopolitical import of atomic weapons, at one point delivering a sober-minded speech in the Senate proposing various diplomatic ways of assuaging Soviet fears that the United States would initiate atomic war.

American officials were confident not only in their atomic monopoly, but also that the United States was sitting on top of the world technologically, politically, and economically. On April 4, 1949, the country had joined Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, and the United Kingdom in creating the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to resist Soviet expansionism. Shortly thereafter, the Soviet blockade of Berlin ended with the reopening of access routes from western Germany to the city. Having proved a seemingly limitless ability to resist Stalin’s draconian tactics, and having inflicted considerable damage on Soviet-controlled eastern Germany’s economy via a retaliatory trade embargo, the newfound Western alliance seemed indomitable. Truman himself, buoyed by his 1948 election victory and the validation of his foreign policy in Berlin, was confident that the USSR lagged behind on every measure of power in the postwar world, including atomic weaponry.

Soviet and ex-Nazi rocket specialists were working on an improved version of the V-2, with a power plant capable of a thrust yield of at least eight hundred thousand pounds—fifteen times greater than the wartime V-2. Because the USSR lacked America’s network of strategic air bases around the world, Stalin was betting on intercontinental ballistic missiles to project Soviet power abroad.

In the early postwar years, American intelligence severely underestimated the USSR’s atomic capabilities, but that blissful ignorance was soon to be shattered. On the afternoon of September 22, 1949, Senator McMahon received a summons to the White House, where at 3:15 p.m. ushers escorted him into a top-secret meeting with President Truman. Before almost any other American, McMahon heard the disturbing news that, three weeks earlier, at the Semipalatinsk in Kazakhstan, the Soviet Union had detonated its first atomic bomb, nicknamed “Joe 1.” A shocked McMahon promised Truman he would not leak the classified briefing to the press. As he drove home that afternoon, he was full of trepidation. Eyeing happy-go-lucky children on playgrounds, watching their purpose-driven parents doing family errands, he felt his heart sink, cognizant that Americans were in their last carefree hours of postwar innocence. The world was about to get more dangerous and complicated.

That evening, Truman paced around the White House, sipping bourbon. The world order had changed: there were now two nuclear superpowers. But the president’s greatest fear wasn’t the obvious one: that the Soviets would attack the United States with nuclear weapons. Instead, he intuited that when the public learned that Joseph Stalin had an atomic bomb, the shock could trigger a panic, and recriminations were sure to be unleashed against his administration for having underestimated Soviet capabilities. The next day, when the rest of Congress and the public received the news, lawmakers would have to tread carefully not to frighten the country or fan the flames of war.

Congressman Kennedy deliberated on the Soviet feat in Kazakhstan for two weeks before speaking out via an open letter to President Truman, warning that the Department of Defense had reneged on its obligation to prepare American citizens to survive atomic warfare. Less interested in how the Soviet scientists had achieved nuclear parity, Kennedy seized the issue of civil defense as his calling card. Remembering the woeful lack of U.S. military preparedness in the 1930s, he wrote of “an atomic Pearl Harbor” unless the United States spent “months and even years” planning ways to resist or respond to and survive the catastrophic event of a Soviet atomic attack.

Nobody paid much attention to Kennedy’s theatrics. Journalists denigrated the letter as the act of a publicity-hungry young politician who was good at turning a phrase. The Truman administration turned to McMahon to counter Kennedy’s alarmism. The Connecticut senator dismissed the young Massachusetts congressman’s civil-defense siren call as novice humbuggery. The United States, McMahon retorted, simply couldn’t afford to devote the necessary time and expense to the levels of civil defense Kennedy proposed.

Kennedy was playing to the public’s still clear memories of the attack on Pearl Harbor of eight years before. Even though a Soviet sneak attack on Western Europe or North America was unlikely, it was plausible, especially considering the tensions over divided Berlin. In coming years JFK endorsed the idea of the federal government’s printing pamphlets warning the public about post-explosion radiation hazards, and having schoolchildren learn how to seek shelter if a nuclear flash occurred. But his well-intentioned civil-defense mantra was too simplistic. While building superhighways to escape American cities quickly in the event of a Soviet attack had public works merit, defense strategists such as McMahon knew that actually preventing World War III would be a much more complicated endeavor. It would take the slog of intense U.S.-Soviet diplomacy, and it would also require the United States to build multistaged rockets and hydrogen bombs. And this would mean the United States’ developing a sophisticated ICBM program capable of delivering nuclear warheads over long distances. If the USSR could blow America up fifteen times over, America had to build a missile deterrent that would wipe out the USSR fifty times. If the Soviets were mobilizing science and technology in peacetime, so would the Americans. McMahon’s thinking framed the Cold War until the USSR’s collapse in 1991.

As the national debate unfolded, Kennedy moved beyond his initial civil-defense stance and took a similar but more conventional tack, arguing that the best way to avoid atomic war was for the United States to build up its troop levels; throw billions into modernizing the army, navy, and air force; and stay on a permanent wartime footing.

Unusual for two Democratic leaders, Kennedy and McMahon agreed that President Truman, one of their own, was partly to blame for Stalin’s atomic advancements. But their thinking was part of an anticommunist fervor that swept across the country in 1949. When, on October 1, 1949, the Chinese Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek fell to the Communists under Mao Zedong, Americans woke up believing that Stalin and Mao were intent on burying U.S. capitalism.

THE DOUBLE WHAMMY of the Soviet nuclear bomb and the Chinese Communist Revolution reinforced Kennedy’s tough-minded anticommunist side. The fact that his father despised Stalin made his political stance that much easier. At the same time, Jack realized that it was far wiser, politically, to couch his anti-Sovietism in terms of advancing global peace rather than stoking fears of an impending nuclear war. He knew that communism had to be resisted, whether one sought peace through disarmament or through massive military deterrence. American relations with the Soviets, JFK believed, had to be a mixture of aggression and accord.

In April 1950, while Kennedy was approaching his third congressional race, President Truman received National Security Council Paper Number 68 (NSC-68), a top-secret report that argued for a massive buildup of the U.S. military and the nuclear arsenal to counter the Soviet threat. This document laid the groundwork for American Cold War policy for the next two decades.

On November 7, 1950, Kennedy beat Vincent Celeste to win a third term in Congress. Throughout the Korean War, which had started earlier that year, JFK regularly called for enormous increases in the U.S. military budget. An avatar of constant vigilance against communism, he applauded Truman for authorizing the development and deployment of U.S. thermonuclear missiles, B-52 bombers, supercarriers, tanks, and other heavy weapons. But Kennedy considered Truman’s foreign policy feckless, and he regularly criticized the president for weakness against the Soviets, the stalemate in Korea, and a general unwillingness to stop the “onrushing tide of communism from engulfing all of Asia.” To the surprise of Democratic liberals, Kennedy distanced himself from the revered George C. Marshall and State Department hands such as John Fairbank and Owen Lattimore for allowing the Nationalist government of China to collapse. Although Kennedy was a traditional liberal on domestic issues such as Social Security, the minimum wage, taxes, and education, he was a pronounced anti-Soviet, pro-military hawk like few other congressmen in his party. Just as nobody—not even Senator Joe McCarthy, a family friend—could accuse JFK of being weak on communism, nobody could accuse him of being a party regular. “I never had the feeling,” Kennedy said privately, “that I needed Truman.”

In April 1950, von Braun and his group of around 125 German scientists and engineers brought to the United States by Holger Toftoy under Operation Paperclip were transferred from Texas to the Army’s Redstone Arsenal, in Huntsville, Alabama, home of the newly renamed Ordnance Guided Missile Center (OGMC). Overall, a thousand personnel were assigned to help von Braun develop what soon became the Redstone rocket. Situated in the Tennessee River Valley, surrounded by rolling hills and caves, Huntsville was a garden paradise compared with arid El Paso. There was no ambiguity about what their mission was building: tactical ballistic missiles of mass destruction, not spaceships. Toftoy, then a brigadier general, would soon command von Braun’s team in Alabama. (In early 1956, the newly formed Army Ballistic Missile Agency [ABMA], under Major General John Medaris, would take charge of the entire Huntsville operation.)

Speculation was rampant in 1951 that Kennedy would run for Senate the following year. Fresh from a five-week European tour, the young congressman testified before the Senate Foreign Relations and Armed Services Committees on how best to defend Europe against Soviet influence and control. That May, he introduced a bill seeking to restrict U.S. companies from trade with “Red China,” and in early fall he embarked on an extended trip to Asia, visiting Hong Kong, India, Vietnam, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, and Thailand. In addition to burnishing his foreign policy credentials, Kennedy’s travels confirmed his belief in the necessity of containing communism.

Around Capitol Hill, Kennedy continued to be best known as the House’s resident playboy. The Washington Post teased that the “current emotional heat wave on Capitol Hill is attributed to bachelor Representative John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts.” According to the newspaper, women working in the U.S. Capitol “peek their heads around corridors and have heart palpitations when word spreads that the young lawmaker is approaching.” Always smiling boyishly, his teeth a bright white, Kennedy inspired more than workplace crushes; his personal magnetism was an asset in selling the Democratic Party brand. The question hovering over the PT-109 heartthrob was whether he’d ever marry. Then, in May 1951, he met Jacqueline Bouvier at a dinner party and was smitten—though that didn’t stop him from chasing other women. “I knew Jack and he was a playboy,” recalled John Lane, a senior aide to Senator McMahon. Lane and Kennedy were similar in age, both Irish Catholics from New England, educated at first-rate colleges, and brimming with the ambition to make good in Washington. “A nice guy,” Lane continued, “riding around in the Cadillac convertible with the top down, living it up in Georgetown, because I lived it up there too at the same time.”

Though Kennedy lived with a certain esprit and had found a way to use his youthful verve to draw in voters on his own terms, he worked hard to develop a more heavyweight reputation in the halls of Congress. As to his fans among the women at the Capitol, the Post added that Kennedy “assiduously dodges them with an inimitable Irish grin and sticks to his legislative duties.” Even if his team—or his father—wasn’t directly responsible for the addition of that sentence, they could have pointed to the frothy Post article as a template for hundreds of Jack Kennedy profiles to come: he was as charming as a matinee idol, but also a staunch anti-Soviet orator. Nevertheless, Kennedy didn’t earn the gravitas he sought in the House, where he chafed at the need for legislative patience. He knew you had to be in Congress many years before you had real power and influence, or an opportunity to play a historic role on substantive legislation.

Congressman Kennedy remained constantly aware of his father’s expectations, which had pointed at the White House since his sons were in swaddling clothes. The pressure to succeed may have been paternal, but the need to act quickly came from Jack himself. Friends who knew him in the House said he treated his life as though death were knocking, making the most out of every day. In this, his health was a major factor: in addition to the digestive and neurological maladies he’d endured since childhood, and which still resulted in occasional hospital stays, he also had near-constant back problems, causing bouts of blinding pain and sometimes necessitating the use of crutches. Additionally, he’d been diagnosed in 1947 with Addison’s disease, a dysfunction of the adrenal gland that can cause fatigue, abdominal and muscle pain, and depression, among other symptoms.

In his way, Kennedy seemed to have turned his pessimism about his longevity into optimism for all he wanted to accomplish, as soon as possible. And while it’s true his father prodded him to advance in politics, regularly providing money and meddling, Joseph Kennedy’s supposedly overbearing influence has been overblown. “Sometimes you read that [Jack] was a reluctant figure being dragooned into politics by his father,” recalled Charles Bartlett, a close friend of Jack’s who became a syndicated newspaper columnist. “I didn’t get that impression at all. I gathered that it was a wholesome, full-blown wish on his part.”

Jack Kennedy’s political drive was, in part, a reaction to the early deaths of his older brother, Joe Jr., and his sister Kathleen (“Kick”), who’d died in an airplane crash in 1948 at the age of twenty-eight. Close in age, these three Kennedy children had been inseparable in their youth. At thirty-four in 1951, JFK may indeed have felt he was living on borrowed time. Hungering for greatness and steeped in history, he grew eager to move beyond the stultifying House of Representatives.

WHILE KENNEDY DELIBERATED his future, the United States was taking steps that would bring it closer to space.

During World War II, three arsenals centered on the town of Huntsville had manufactured and stored ordnance for the U.S. military: the Huntsville Arsenal, the Huntsville Depot, and the Redstone Ordnance Plant. After V-J Day, these facilities were consolidated to form the Redstone Arsenal, which in June 1949 became home to the new Ordnance Rocket Center, the army’s headquarters for rocket research and development. Once von Braun had been transferred, he discovered that he loved being in northern Alabama. Huntsville was ideal for von Braun’s purposes: the Army already had well-equipped laboratories, large assembly structures, and a dependable firing range. But it wasn’t a place where he could fire large booster rockets into the sky. For that his Redstone rockets would be shipped on giant barges on the Tennessee River, which flowed into the Atlantic Ocean. Coinciding with von Braun’s move to Alabama was a new rocket launchpad at Cape Canaveral, Florida, where his “babies” would be launched toward the stars. He was frustrated that the U.S. Army was building rockets “at a tempo for peace.” Nevertheless, he remained dutiful to the Army and had a born-again Christian conversion, which gave him faith in the future. “We are,” von Braun enthused upon resettling, “going to make history here.” A further frustration for him was that his novel Mars Project, anchored in the uplifting prose of Jules Verne (but larded with empirical science), struggled to find a publisher; it was turned down by nineteen for being “too fantastic.” Nevertheless, von Braun remained convinced that landing on the moon was doable in his lifetime. And he believed Mars was reachable in the mid-twenty-first century.

Redstone became the namesake for a new class of von Braun–designed suborbital ballistic missiles that were direct descendants of the V-2 rockets, and Huntsville became an epicenter of Cold War industrial mobilization. In a strange twist, von Braun and his team were tasked with essentially building V-2s with nuclear warheads on them to be shipped to U.S. Army bases in West Germany. Faced with UN forces fighting a North Korean military armed and sponsored by both the USSR and China, the United States had to master military rocketry and begin full-scale production before attempting to make manned space voyages a reality.

Because America had no usable missiles, the Korean War became a showplace for the air force to prove its new-kid-on-the-block importance. More than one thousand U.S. fighter pilots served in the conflict, and the most effective plane proved to be the F-86 Sabre jet, which could fly at forty-five thousand feet and was armed with machine guns for use in aerial engagements. Because the Truman administration couldn’t risk escalating the war by bombing the mainland Chinese airstrips where North Korea based its Soviet-made MiG-15 fighter jets, those American pilots were kept busy, and fought magnificently. Thirty-nine U.S. pilots attained ace status, downing five or more enemy planes, and three of these brave fliers would go on to become NASA astronauts who intersected poignantly with Kennedy’s career: Neil Armstrong, John Glenn, and Wally Schirra.

ALTHOUGH OTHER POLITICIANS typically campaigned for Senate in their forties or fifties and usually boasted a distinguished political record, thirty-five-year-old Jack Kennedy was determined to make his bid for the Senate in 1952, taking on popular Republican senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. He could have waited for 1954 and run against the more vulnerable of Massachusetts’s senators, Leverett Saltonstall, but he was loath to waste two years. JFK was fired up, and 1952 would be his year. His younger brother Robert would, for the first time, be his campaign manager. Joe Sr. started working the phones and called Connecticut senator Brien McMahon, who was going after the Democratic presidential nomination after Truman announced that he would not seek another term.

“McMahon was home ill when Joe Kennedy called him,” recalled John Lane. “I walked in when he was talking to him on the phone. He hangs up and he says, ‘Joe is going to enter Jack.’ I said, ‘Jack Kennedy for the Senate? Really? . . . My God!’ But he said, ‘I’d rather have a Kennedy in the Senate than a Lodge.’”

Gruff in the way of a friendly bear, McMahon was far unlike Jack Kennedy in temperament, but the self-described Cold War Democrat had staked out much the same ground as Kennedy, and he was someone the younger politician watched closely. In 1952, McMahon was well prepared for the presidency, his only worry being the glass ceiling of his Catholic faith, which had perhaps foiled the candidacy of New York governor Al Smith in 1928. On that score, McMahon thought perhaps he might just be the one to finish the job and win the White House—but it was not to be. Just as he started his campaign, pitching a platform of ensuring world peace through fear of atomic weapons, he was diagnosed with lung cancer and withdrew to wage a more personal battle. He died three months before the election.

Kennedy’s Senate opponent, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., was a moderate Republican from one of New England’s most prominent families. Lodge’s grandfather had been Theodore Roosevelt’s sturdiest ally in the Senate, and one of his brothers, John Davis Lodge, was currently the governor of Connecticut. Henry Lodge himself, then fifty, was a seasoned politician who had resigned from the Senate during his second term to serve in World War II, where he earned a chestful of medals for valor under fire in France and Germany. Hollywood handsome, dapper, and with a fine patrician accent, he was a formidable presence on the American political stage. Next to Lodge, almost any rival would have seemed callow, and the young Jack Kennedy seemed especially green.

But Kennedy, with three successful congressional races under his belt, waged an exemplary fight. The embodiment of poised drive, he traveled tirelessly throughout his home state, appearing before small groups that added up to hundreds of thousands of voters who could go home and say, “I met John Kennedy today.” The Saturday Evening Post reported that Kennedy was “being spoken of as the hardest campaigner Massachusetts ever produced.” Meanwhile, by backing Dwight Eisenhower, a moderate, over the conservative Robert Taft for the Republican presidential nomination that year, Lodge alienated the right wing of his party; they would stay home on Election Day. In addition, during campaign season, he was often elsewhere in the country, playing the elder statesman. Although both candidates used advertising extensively and spoke whenever possible before large Massachusetts crowds, the personal style of the Kennedy team made a difference, with brother Robert ably serving as Jack’s campaign manager and Joe Sr. exercising his phenomenal fund-raising prowess. Channeling the spirit of the times, Kennedy praised the Strategic Air Command decision to deploy Convair B-36 Peacemaker and Boeing B-47 Stratojet long-range nuclear bombers on “Reflex Alert” at overseas bases such as the purpose-built Nouasseur Air Base in French Morocco, placing them within unrefueled striking range of the Kremlin.

The 1952 campaign ground on. In late July, after he’d withdrawn from the Democratic presidential race, Brien McMahon listened to the national convention on radio from his hospital bed in Hartford and heard the Connecticut delegates award him all their votes on the first ballot. Once the other states voted, Governor Adlai Stevenson of Illinois was chosen as the Democratic standard-bearer. From his sickbed, McMahon told the convention leaders by telephone that if Stevenson won, he should immediately instruct the Atomic Energy Commission to mass-produce thousands of hydrogen bombs. A few days later, McMahon was dead. He never got to see his dream of the United States testing its first thermonuclear bomb, which occurred just months later, on November 1, 1952. In some respects, McMahon’s death was John Kennedy’s gain. As John Lane later recounted, “Kennedy told me later that if McMahon hadn’t died he [Kennedy] probably would have never gotten a chance” to run for president in 1960.

ON ELECTION DAY 1952, Kennedy won a surprise victory in his Senate race even as Republican Dwight Eisenhower won the presidency. The sixty-two-year-old Eisenhower, whose great balding head and fine smile reassured voters of his natural leadership skills, would be the first Republican to occupy the White House in twenty years. A West Point graduate, “Ike” had the distinction of a meteoric rise, climbing over three short years from the rank of colonel in 1941 to that of five-star general, and Supreme Allied Commander, by 1944. After the war, Eisenhower served as army chief of staff from November 1945 until February 1948, then retired and moved into academia as the president of Columbia University. Still looking for his next role as he entered his sixties, he was courted by both political parties, with no less than James Roosevelt, son of Franklin and Eleanor, trying to entice him onto the Democratic presidential ticket. The Republicans won out, and though conservatives hoping to control the party had their doubts about him, Ike brought their party the White House—and they, along with the rest of the nation, waited to see just what kind of president he would turn out to be.

With Harry Truman leaving the presidency with an approval rating of under 30 percent, the Democrats also faced a void of leadership as the Eighty-Third Congress convened in January 1953. Their presidential candidate, Senator Adlai Stevenson, was liked and respected, but his defeat left room for hungrier and louder Democratic voices. Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas, who became the Senate minority leader as Kennedy entered the upper house, was the prime example. Like Kennedy, Johnson had felt stifled in his earlier days in the House; moving on to the Senate in 1948, he thrived there. Even without seniority, Johnson managed to dominate through his mastery of policy and the legislative process. A born politician from Texas Hill Country, he could keep the endless minutiae of issues prioritized simultaneously with the nuances of his colleagues’ needs. Nobody in politics worked a telephone or Senate floor (and its back rooms) better than Johnson. And in person, using gesticulating hands and a surprisingly hard grip to his advantage, he came across as a force of nature.

Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota was the unabashed New Dealer among Senate Democrats at the time Kennedy arrived in the upper chamber. A doctrinaire liberal with strong ties to the labor movement, Humphrey had made his reputation at the 1948 Democratic National Convention with a rousing speech on civil rights, for which the Deep South never forgave him. Taking a Senate seat the following year, he championed lost causes and ruffled the feathers of more conservative Democrats. His colleague Robert C. Byrd of West Virginia recalled the time that Humphrey rose during a discussion of Senate committees “to demand the abolition of the Joint Committee on the Reduction of Nonessential Federal Expenditures as a nonessential expenditure.” It wasn’t as funny then as it sounds now; Humphrey’s constant questioning made enemies of many pork-hungry senators that day. By the time of Kennedy’s arrival, Humphrey had smoothed his ways and become known as a dogged legislator, someone not as manipulative as Johnson but with a fund of Minnesota decency that could bring him labor and farm support when it was needed.

Jack Kennedy avoided the rookie mistakes that Humphrey had made. After fumbling his opportunities by sidestepping House committee leadership roles from 1946 to 1952, he was more attentive and cooperative in his new Senate role, and felt revitalized working on a variety of bills and projects. Determined not to be confined to championing projects that would help only Massachusetts, he vocally supported the Saint Lawrence Seaway, disregarding his home state’s worry that connecting the Great Lakes to the Atlantic would hurt Boston’s seaport business. He also enjoyed the Senate’s clubbier, more elitist atmosphere, which harked back to his experiences in prep school and the Ivy League. Eloquence was expected, and so were manners. They weren’t always delivered, as in the case of the unpredictable Lyndon Johnson, but Kennedy could, without pretension, quote Milton’s poetry in his speeches and mention Roman philosophers, certain that he didn’t need to explain every reference to his colleagues. While he had always refused to insult audiences by simplifying his rhetoric in public, he seemed inspired to up his game in his speeches in the Senate. For Kennedy, the Senate was about power, and every member had a healthy measure of it. If he had come to the conclusion that the vast majority of representatives were irrelevant, he saw that every senator counted. Toward the end of his life, an old friend asked him what he would like to do after the presidency, and Kennedy replied that he’d like to be a senator or journalist once more.

Because Kennedy’s civil-defense advocacy fell flat, he needed a signature issue, and just months after Eisenhower was sworn in, he decided he had one. At issue, remarkably, was the war hero president’s disinclination to grow the military. After only six months in the White House, in July 1953, Eisenhower pulled America out of the Korean War, which had cost more than 34,000 American lives. Following what was later dubbed his “New Look” defense strategy, Eisenhower ordered a 25 percent reduction in military funding and demanded accountability from Pentagon planners who had for years slipped their massive pork plans past the accommodating Roosevelt and Truman. The commander who had masterminded D-day, the largest naval offensive operation in the history of the world, didn’t believe in maintaining a gargantuan standing army poised for limited Korea-like ground wars. Nor did Eisenhower trust an economy dependent on weapons production for prosperity. Eight years later, in his farewell address upon leaving the presidency, Eisenhower famously warned about the dangerous influence of what he called “the military-industrial complex.” Less well remembered is that Eisenhower started his presidency on this same note, with a plea to avoid what he called the “burden of arms. . . . Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed.”

Eisenhower’s rollback of military funding perplexed Jack Kennedy, who complained that the president’s New Look, the name given to Ike’s national security and defense policy, lacked coherence. This brought Kennedy’s voice into the national debate, where his youthful dynamism stood in cosmopolitan contrast with Eisenhower’s steadier, Great Plains low-key style. But JFK’s barbs lacked bite and weren’t a mature public policy issue. For that, Kennedy kept jabbing and searching. On September 7, with the death of Joseph Stalin in March 1953 and the eventual choice of Nikita Khrushchev to become the new Soviet leader Kennedy seized the personal opportunity of this new Cold War dynamic. While Khrushchev won praise in some U.S. foreign policy circles for the de-Stalinization of the USSR, Kennedy railed against him endlessly. At the same time, he burnished his anticommunist credentials with surprisingly robust support for Senator Joseph McCarthy, who claimed that Communists had infiltrated the State Department, the CIA and the U.S. atomic weapons industry.

Although the Eisenhower administration was attempting to shrink the military overall, it supported air power, especially in its most modern incarnations. Because the United States had first-rate intercontinental bombers and had enjoyed indisputable air superiority in the Korean War, the air force had not prioritized development of ICBMs at a level comparable to that of the Soviets. But with the USSR testing a hydrogen bomb on August 12, 1953, and American scientists developing smaller, rocket-mountable nuclear devices, the air force had to catch up. Eisenhower, in his postpresidential memoir Waging Peace, criticized Truman for grossly deprioritizing long-range ballistic missile technology during his White House tenure. To put this into perspective: in Truman’s last year, defense spending appropriations for ballistic missiles was only $3 million; Eisenhower, by contrast, a few years later had jacked them up to $161 million.

On August 20, eight days after the Soviet hydrogen bomb test, the first of von Braun’s Redstone missile was test-fired by the army at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Developed over the previous three years by von Braun’s team at the OGMC, the Redstone would go on to be the workhorse of the army’s missile program. Von Braun, conditioned to the challenge of funding rocket research ever since his days with Hermann Oberth, believed he could advance his cause by framing U.S. ballistic missile development as necessary for competing with the Soviets. There were other great rocketeers in America (notably, the team assembled by Frank Malina at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory from the 1930s to the 1950s), but they didn’t have an engineering wizard-cum–media maven like von Braun to promote their engineering feats.

Von Braun loved to boast publicly that the United States was destined to become a spacefaring nation. He wrote three articles for Collier’s in 1952 that envisioned launching humans to the moon and a wheel-shaped space station. These articles made a splash. Collier’s promoted von Braun as an anti-Soviet German engineer and debonair aristocrat who loved the United States. His prose was highly readable. In one article he coined the phrase “across the space frontier” in Collier’s. Armed with an accumulation of rocket engineering knowledge, he seized the attention of the magazine’s four million readers, but his space advocacy came with a stark warning that the United States must “immediately embark on a long-range development program” or lose out to the Soviet Union. In 1953 and 1954, von Braun wrote articles for Collier’s about satellites carrying monkeys and Mars exploration.

What von Braun understood was that in a democracy, where taxpayers footed the bill, space exploration would happen only with direct and unvarnished mass appeals for international prestige, beating Russia, and being first. His McCarthy-era thesis that the United States must “conquer” space had a Manifest Destiny feel. And his notion that an American-manned space station could be constructed with existing rocket techniques and that, in addition to its uses as a scientific observatory, it could also act as an orbital fortress, dominating Earth as an impregnable launching base for atomic missiles, was alarming. It was up to the United States, von Braun argued, to see that nobody else built one first. “You should know how advertising is everything in America,” he told a friend. “The way I’m talking will get people interested [in space exploration].”

Call him an ex-Nazi propagandist, P. T. Barnum–style marketer, or space visionary, but von Braun understood explicitly that space travel had to be couched in the spirit of American exceptionalism. This attitude went against President Eisenhower’s belief in holding down expenditures and allowing the private sector to play a large role in shrinking the size of Big Government. Von Braun’s saber rattling for the army about conquering the Soviets in space, however, was embraced by those anticommunist Democratic senators with presidential ambitions: Stuart Symington, Lyndon Johnson, and John F. Kennedy. And in 1954 the air force started developing a reconnaissance satellite program, which historians consider the first U.S. government–funded space program.

ON SEPTEMBER 12, 1953, Jack Kennedy married Jacqueline Bouvier in an elaborate wedding in Newport, Rhode Island. Proud to have descended from French aristocracy, Jackie, as she was called, once stated her ambition as being the “Overall Art Director of the Twentieth Century!” Her sense of fashion and culture leaned highbrow. She had grown up in a wealthy family with residences in Manhattan; East Hampton, Long Island; McLean, Virginia; and Newport. In 1947 she was voted Debutante of the Year at Vassar College. Many Brahmins joked that Jack Kennedy had clearly married up, that Jackie was the best thing ever to happen to the serial dater from Cape Cod. In October, the newlyweds were interviewed from their Boston apartment on Edward R. Murrow’s CBS show Person to Person, and were turned into Cold War–era celebrities.

While the Kennedys were on their honeymoon, a report that had been commissioned by the Truman administration nineteen months earlier was delivered to Eisenhower. Titled “The Present Status of the Satellite Problem” and prepared by Aristid V. Grosse, a physicist at Temple University who had worked on the Manhattan Project, the report relied heavily on interviews with von Braun and other Huntsville scientists, and laid out the certain propaganda boon that would accrue to the Soviets were they to launch a satellite before the United States. The last paragraph of the report read:

At the present time our engineering efforts in this field are limited in scope and distributed over various government agencies. It is recommended as a first step in solving the satellite problem that a small but effective committee be set up composed of our top engineers and scientists in the rocket field, with representatives of the Defense and State Departments. This Committee should report to the top levels of our government and should have for its use and evaluation, all data available to our government and industry on this subject. It should report in detail as to what steps should be taken to launch a satellite successfully into outer space and to estimate the cost and time required for such a development. It is felt that if such a committee were in existence and a definite decision taken by our government regarding the construction of a satellite, that it would fire the enthusiasm and imagination of our engineers and scientists and effectively increase our success in the whole field of rockets and guided missiles.

This Grosse report didn’t immediately jump-start the U.S. satellite program under Eisenhower. But the arguments it raised were reviewed with fresh eyes in 1954. CIA director Allen Dulles also understood that the United States needed to lead the world in satellite technology. A year after the Grosse report, Dulles wrote the Department of Defense that if the Soviets beat the United States in this field, it would be a major Cold War setback. “In addition to the cogent scientific arguments advanced in support of the development of Earth satellites,” Dulles said, “there is little doubt but what the nation that first successfully launches the Earth satellite, and thereby introduces the age of space travel, will gain incalculable international prestige and recognition. Our scientific community as well as the nation would gain invaluable respect and confidence should our country be the first to launch the satellite.”

IN THE SUMMER OF 1954, Kennedy was suffering chronic pain due to college football and war injuries, along with osteoporosis likely caused by steroid treatment for colitis and failing adrenal glands. Because of his Addison’s disease, back surgery was risky, with only a fifty-fifty chance of survival, but Jack chose to undergo the operation at a New York hospital that October. Ironically, when Lyndon Johnson suffered a heart attack on July 2, 1955, and was placed in a Washington-area hospital for seven weeks, Kennedy’s stature in the Senate rose considerably on the incorrect presumption that he was healthy and vigorous in comparison to the ailing Senate majority leader.

Speculation swirled that JFK might get the second spot on the Democrats’ 1956 presidential ticket. While the chances of defeating Eisenhower were scant (even though he’d suffered cardiac arrest in 1955), several prominent Democrats, including Johnson, chose to run for the top slot. After Adlai Stevenson won the nomination for the second time, Kennedy was among the few who sought to join the ticket, calculating that the VP slot would put him in the national limelight and position him for the top of the ticket in 1960, when the popular Eisenhower would no longer be eligible. JFK’s easy good looks and carefree smile made him an attractive guest on television, the exciting new medium for selling a candidate, even if he sometimes came off on the air as cautious and mechanical. After three ballots, Kennedy lost to Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee, a loss that deprived Jack of his stepping-stone but proved he could be taken seriously at the presidential level. What handicapped Kennedy was his vote against an Eisenhower bill to bolster farm prices. “This was the first time in his political career that Jack Kennedy had tasted defeat,” historian Robert Caro wrote in The Passage of Power, “and it was apparent that he didn’t like the feeling at all. Yet not only his words but his demeanor, if resigned and disappointed, had been gracious—the demeanor of a young man dignified, even gallant, in defeat.”

After the Democratic ticket of Stevenson-Kefauver was defeated that November, Kennedy began preparing his run for the White House in 1960.

IN EARLY 1957, Senator Kennedy began publicly criticizing Eisenhower’s lagging missile buildup. Although Eisenhower had designated the air force’s Atlas ICBM program a top national priority in 1954, JFK believed it was too little, too late. Full of von Braun–like “the Russians are coming” alarm, he contended that Ike had neglected to properly fund both missile and satellite research and development. While Lyndon Johnson had been making many of the same arguments since the Truman administration, his criticisms had been contained largely to government settings, leaving it to Kennedy to take the case to the public. JFK’s argument caught fire on August 26, 1957, when the Soviets announced that they’d successfully tested the first nuclear-tipped ICBM capable of reaching the United States within minutes.

Kennedy railed against lackluster administration policies that, he claimed, had led to Soviet domination in ICBM development. Having been raised in a family obsessed with winning at every level, he reduced the complexities of Cold War statesmanship to a simple contest. Who was the first to have something both wanted? Who had more of something both feared? Who was ahead? Who was behind? Kennedy outlined geopolitical strategic initiatives that would allow the United States to surpass the Soviets in military strength (especially in missiles) and, at the same time, he declared, encourage peace.

On June 11, two months before the Soviet ICBM test, at long last the U.S. Air Force had launched a liquid-fueled Atlas rocket. It stayed airborne for only twenty-four seconds before imploding into a curtain of fire—seemingly proving Kennedy’s contention that America was lagging behind the USSR in ICBM capability. But the setback didn’t worry Eisenhower much. The glitches and kinks would get worked out. And the United States, he knew, was doing exceedingly well with its solid-fueled missile programs such as the Minuteman, Polaris, and Skybolt.

Advancements in technology were proving helpful to the American effort. The silicon transistor, invented at Bell Laboratories in 1954, revolutionized the world of electronics and silicon became the fundamental component upon which all space computer technology rested. (Before the transistor was perfected, the NACA in Virginia hired women, many African American, to be “human computers” performing difficult calculations by hand.) It was the transistor that helped reduce the size of the computer. In 1946, a single computer with the power of a basic PC today would have been the size of an eighteen-wheel truck and would have needed the same amount of power as a medium-size town. The first silicon transistor in 1954 was about half an inch (gargantuan compared with today, when a cluster of transistors can comfortably fit on the head of a pin), and the first commercially marketed transistor radio, the Regency TR-1, went on the appliance store market for $49.99 in 1954. Visionary aerospace engineers understood long before the general public that the more transistors that engineers could squeeze into a chip, the more speed and power efficiency one could reap.

JOHN KENNEDY FINALLY had his national issue in Eisenhower’s alleged indifference to technology. Over the next three years he’d turn the “missile gap” itself into a weapon. Experts at the time questioned the relevance of numerical advantage when it came to missiles, given that so many other factors impacted the efficacy of nuclear weapons. They also wondered where Kennedy had gleaned the hard-to-prove data that America was falling behind; by many measures, the “gap” was far smaller than he asserted. But JFK had learned that his message rang loudest when it was boiled down to a score. Realizing that sports analogies resonated with the American electorate, he had given Americans the simplest of yardsticks by which to measure a Cold War world where technological development was racing to the edge of the unknown.

Nevertheless, Kennedy was right that the Soviets had turned rocketry into an unprecedentedly potent military weapon, a Kremlin strategy that stemmed from the immediate aftermath of World War II. In May 1945, the Soviets had been aghast when the United States absconded with the top level of Nazi rocket scientists and their research, minus any coordination with their supposed allies. Even though distrust between the two nations was already brewing on many levels, the American raid of Peenemünde contributed to the Soviets’ fear that the United States sought world domination, and it acted like a cattle prod on the Soviet scientific community.

As long as Stalin was alive, the USSR proceeded as though World War II had never ended. Until his death in 1953, Stalin gave priority to the production of atomic weapons, as well as to the rocket science that would combine with it to produce the ICBM. While military technology was treated as a matter of life and death by Stalin, other sectors of the Soviet economy stalled, including consumer goods and other civilian needs. These privations gave rise to a long line of jokes in America, such as the one about a Soviet engineer rushing in to see his boss: “Sir, we have done it, we have built an atomic bomb so compact, it can fit into a suitcase!” The boss looked glum: “But where are we going to get a suitcase?”

Compared with America’s scattershot, underfunded initiatives, the Soviets’ largely classified efforts in ballistic missile and satellite technology were quite advanced. In April 1955, they’d announced the formation of a Commission for Interplanetary Communications in the Astronomics Council of the USSR Academy of Sciences, to work on satellite development. Meanwhile, the Soviet missile program was well organized, leveraging captured Nazi scientists, the theoretical legacy of the late Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, and the technical wizardry of their chief rocket designer, Sergei Korolev. Luckily, however, the U.S. Army had perhaps the only rocket engineer more advanced than Korolev: von Braun.

Meanwhile, Eisenhower was most concerned about finding innovative ways to minimize a surprise Soviet missile attack—Pearl Harbor redux, only with weapons of mass destruction. The burning desire to peer into Soviet territory; to identify what Khrushchev’s military was up to; to photograph the major military posts, nuclear zones, missile factories, bomber plane runways, and the like, via U.S. strategic reconnaissance, consumed Eisenhower. At that time, in the mid-1950s, only U.S. aircraft overflight and camera-loaded high-altitude balloons were available for the huge job. Neither method was both safe and reliable. So Eisenhower decided to approve the air force’s building of high-altitude U-2 spy planes, which could ostensibly fly undetected, even over Moscow, by Soviet antiaircraft technology or advanced radar. And Eisenhower approved the development of space satellites that could, once perfected, spy on the USSR with near-zero danger of being destroyed by Soviet air defenses. These satellites had the big bonus of perhaps not being banned by international law. Space was a new field of human endeavor and lawyers had not firmly established what was legal and what was unlawful once a man-made object left Earth’s atmosphere.

For Eisenhower, establishing a doctrine of “freedom of space” was a paramount national security concern. In 1955—the same year von Braun became a naturalized U.S. citizen—Eisenhower plotted the peaceful exploration of space on pure scientific grounds. Three years before, the International Council of Scientific Unions had proposed the “International Geophysical Year” (IGY) to coincide with the high point of the eleven-year cycle of sunspot activity, occurring between July 1957 and December 1958. Uniting scientists from around the world, the IGY would allow for coordinated observation of various geophysical phenomena (including cosmic rays, the aurorae, the ionosphere, solar activity, geomagnetism, and gravity) and would encompass earth sciences such as glaciology, oceanography, meteorology, seismology, and accurate longitude and latitude determinations. Sixty-seven countries would take part, along with four thousand research institutions that would freely share their data. Promoted by the United Nations, the IGY effort won the support of both the United States and the Soviet Union, and both superpowers announced plans to launch satellites in the name of global peace.

Almost obligated to participate, Eisenhower resisted any pressure to show U.S. superiority by rushing a satellite launch, instead proposing to choose among three programs that were already on track. The first was the army’s Redstone rocket, which had been refined by von Braun and his Huntsville engineers. The air force had started late but had made impressive progress with its Atlas and Aerobee Hi rockets, while the navy had poured money into its own Project Vanguard, which hoped to launch a satellite using an upgraded Viking rocket. In the summer of 1957, either the army or air force programs, if properly funded and incentivized, could have launched an American satellite into space. The frustrating truth was that the United States had the technology and know-how to be first, but not the will.

Along with workability, optics were a deciding factor in Eisenhower’s eventual choice. On July 29, 1955, the president announced that the United States would launch a satellite in IGY. The Pentagon, after careful review, chose the navy’s Vanguard rocket because it carried a larger payload than von Braun’s Redstones. The air force proposal wasn’t taken seriously. The National Academy of Sciences and the Naval Research Laboratory were directed to join forces in planning for a Vanguard satellite launch, emphasizing the peaceful nature of America’s space program.

Disgusted that he lost, Eisenhower had established what amounted to a “design contest.” “It is a contest to get a satellite into orbit,” von Braun fumed, “and we [the army] are way ahead on this.” According to Time, in the aftermath of the president’s 1955 decision, von Braun was “specifically ordered to forget about satellite work.” All von Braun could do now was hunger for a president not named Eisenhower; he’d have to wait Ike out to find genuine enthusiasm emanating from the White House for fast-tracking satellites and, eventually, spaceships aimed at the moon. And he quietly worked with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena to be ready for a Redstone (army) launch with a satellite in case the Vanguard (navy) failed.