By this time, if you are the least bit Internet-savvy and the kind of person interested in crafting and DIY culture, chances are you’ve heard of Spoonflower. My friend Gart Davis and I started Spoonflower in 2008 with very little money, but an ambitious idea. We wanted to develop the first website to make it possible for people to create and sell their own fabric designs through the Internet.

Since its modest beginning in a former sock mill in downtown Mebane, North Carolina, Spoonflower has been written about in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, Better Homes & Gardens, Martha Stewart Living, and BUST, as well as in well-known magazines published in Dutch, French, Italian, Spanish, German, and Japanese. The Spoonflower website has been liked and shared, pinned and followed by many thousands of bloggers, Instagrammers, Facebook fans, and Twitterers, and it is safe to say that the once-novel concept of being able to design your own fabric has permanently entered the collective consciousness.

From my standpoint this is enormously satisfying, as you might guess: the stuff of every entrepreneur’s dreams. But, like the character in the Talking Heads song who wonders how he managed to land in the middle of the life he is living, I often find myself disoriented in the midst of Spoonflower’s success. Is this, in fact, my beautiful website? It seems odd, given my background.

This book is primarily about how to design your own fabric digitally (meaning using a computer), but we also show you how to design for other surfaces, such as wallpaper and gift wrap. Each approach to developing a digital surface design is presented in the context of a handful of projects, which we hope you will want to make and/or use as a jumping-off point for further inspiration. No particular experience is necessary to begin. We’ve included lessons and projects for novices and experts alike, from the simple (a pillow portrait of your pet) to the complex (an engineered print of a skirt pattern made from one of your own photos). Whether you’re a quilter, a crafty parent, a professional artist, or an aspiring fashion designer, there are choices here for you.

We set out to create the most approachable book possible. But I should point out that I’m not a designer. I also can’t sew. Neither can my business partner Gart, with whom I cofounded Spoonflower. In fact, not only were we new to the world of fabric and sewing when we started, neither of us knew a thing about printing or, more broadly, textiles. Asked to play casting director for the ideal founder of Spoonflower, I might have sought out someone dapper, knowledgeable, and engaging: the fashion celebrity and design guru Tim Gunn comes to mind. But, alas, I am no Tim Gunn. People who have observed the state of my desk could reasonably question the wisdom of my involvement in any venture intended to promote a more beautiful or elegant anything. Let’s not even bring up my fashion sense. And my partner Gart is, if anything, worse than I am in this respect. So how is it that either of us should have ended up in the business of introducing people to the world of surface design?

Spoonflower was my wife’s idea. Unlike me, Kim is an avid sewist (her preferred term) and fabric collector. She’s a prolific quilter, enjoys making clothes for our three daughters, and in general displays utter fearlessness when it comes to making almost anything, from soap to homemade Pop-Tarts to hats. Spoonflower came about because, in the fall of 2007, Kim was thinking about making new curtains for our den. One night after work, while I sat on the sofa reading, she described to me her vision for the curtains, which would include fabric with giant yellow polka dots. The trouble, she explained from somewhere over my shoulder, was that she had not been able to find fabric with yellow polka dots as large as the ones she imagined.

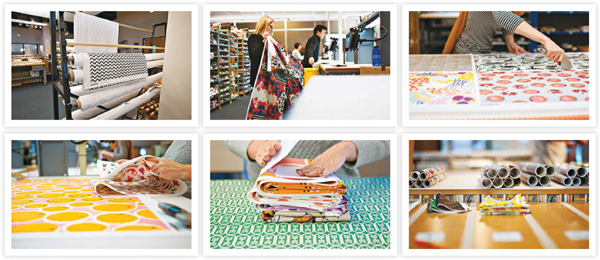

Spoonflower is a busy and colorful place! Here are some snapshots of the facility that show our process, from printing to heat-setting to lovingly packaging orders for shipment.

“Wouldn’t it be cool,” she said, “if there was a place where you could order fabric you designed yourself?” To hear her tell it, I barely looked up from my newspaper. But—and I write this on behalf of husbands everywhere—despite all appearances, I was listening. The wheels were spinning. Partly because of digital technology, we live during a time when the option to customize your own products is, to an astonishing degree, not just common, but expected. Why on earth couldn’t a person like Kim design her own fabric?

In January of 2008, not too long after my conversation with Kim about curtains, Gart and I sat down for coffee in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, to talk about the idea of starting a website that would let people create and sell their own fabric. Gart and I had worked together during the initial four years of Lulu.com, the world’s first Internet-based self-publishing tool for books, a company founded in 2002. It’s where we learned the potential and the pitfalls of self-publishing and print-on-demand. Around the same time, YouTube—which would become the king of all self-publishing sites—was also born.

Although neither of us had much money to invest, we agreed on a course of action that included talking to crafters about the idea and learning more about the technology that would be required to produce print-on-demand fabric. In 2008 there were a few services in the U.S. that offered to print custom fabric for you, but they were, by and large, quite expensive—up to $150 per yard—and none of them had Internet-based business models.

Gart and I were in a great location to learn how to make fabric. As a state whose economy had once relied heavily on textile production, North Carolina was full of textile-related resources. A week after we had coffee to discuss the idea, I was able to go a few miles down the road to Raleigh to visit a lab at North Carolina State University’s College of Textiles and see my first digital textile printer. At another institution close by, a not-for-profit called [TC]2, I was allowed to try one out. The machinery itself didn’t seem complicated. The machines I saw were just big, expensive inkjet printers, larger versions of the sort of device you might use at home to print your photos and documents. In my next conversation with Gart, I effused over a handful of printed fabric samples and relayed the conclusion of my investigations: “We should just buy a printer and try it out. It can’t be that hard.”

Over the next eight weeks or so, Gart and I hurried to develop a rudimentary version of the service we envisioned. When we launched at the end of May 2008, a special invitation was required to use Spoonflower. Invited visitors could upload a single image, preview it, and add up to three yards of fabric to a shopping cart. Over the summer, working from a waiting list, we approved invitations at a rate of a hundred or so new members per week. In July, our confidence had swelled to such a degree that Gart and I took out a loan to buy our own printer and began to look for a space. In August, we moved into a hot-as-blazes former sock mill, which became our first office. By October, a few months later, we finally allowed the thousands of people on our waiting list to use Spoonflower for the first time. Just a few months later, the New York Times ran a piece on Spoonflower on the cover of its Home section titled, “You Design It, They Print It.”

The trouble was, we really couldn’t print much of anything at that point. The printer on which we had spent our meager savings—along with a second printer we’d purchased just before Christmas—was breaking down. We had more customers and orders every day, but were struggling to print any usable fabric. We knew we had to buy new printers, but because the economy had more or less collapsed at that point, no bank seemed willing to lend us the money. With our printers hobbling along, customers and orders were stacking up and our young startup was struggling to pull together the resources we needed to grow. We got some money from NC IDEA, a local technology grant program. A relative of our ink supplier gave us a personal loan. Kim and I scraped a little more cash out of our home equity.

While things looked pretty grim from a financial standpoint, the Spoonflower community was growing. And our customers, many of whom were following the progress of our little startup soap opera, remained enthusiastic and encouraging. And eventually we did get a loan, we did buy more printers, and we managed to keep the business alive and expanding to meet the demand for custom-printed fabric. Two years after we started, Spoonflower moved from the dusty old mill in Mebane to an office down the road in Durham, where our employees gained the benefit of air conditioning and a break room with a kitchen. Today, our office is a bright and bustling place. We have many printers that run around the clock, churning out fabric and paper designs uploaded to our site from all over the world. Our merry crew has grown to over a hundred. We print wallpaper and gift wrap, as well as fabric, and we have an entire R&D team dedicated to exploring and pushing the limits of the technology so we can extend the power of creative individuals to make beautiful things.

So, what began with an idea for new curtains for our living room has now spun out into yet another, perhaps revolutionary, direction: a book. I am reminded of something someone said to me a couple of months after we launched Spoonflower, when the site still required an invitation to join. The person who said it was Colene McCord, a 70-year-old woman from Knoxville, Tennessee, who was a lifelong friend of my mother. She raised her eyebrows with astonishment when I explained our new business idea. “That’s amazing! You know all my life I’ve wanted to design fabric. Really. When I lie in bed at night and I can’t sleep, that’s what I do. I design fabric in my mind.” Colene is not a designer or an illustrator. She doesn’t have skill with a computer. She is a creative person, a person interested in self-expression and beauty and design and pattern. Many, many people share a passion for such expression. It’s a thread that runs through many panels of their lives, perhaps showing up as cooking in one person, as gardening in the next. This book is about the joy of making something mingled with the challenge of learning new things. Thanks for picking it up. I can’t wait to see what you do with it.

Early on in Spoonflower’s history, we developed the idea of holding fabric design contests that anyone could enter. Each week, we would announce a theme, take submissions, and then post all the entries on the same day on our website. Visitors could vote for the designs they liked best. We wanted to make the contest low-key and fun, with a nominal prize of free fabric. We had two goals: first, engage designers by giving them a new challenge each week, and second, showcase designs and photos of printed fabric to inspire new visitors to our site.

At the beginning, the themes of our contests were quite simple—Halloween, Christmas, and so on—but over time they evolved to become more arcane so each contest would be unique. Because we wanted to encourage new work, we also tried to develop themes that would dissuade people from entering designs they’d already created. Surrealist Fruit. Steampunk. Tattoos. Tessellations. Robots. Cocktails. We held a contest for fabric designs created exclusively using crayons, and another for designs featuring fish that used a set palette of colors. We developed a discipline around the weekly contests that included the invention of themes and outreach like a weekly email and Facebook post; an entire section of the site became devoted to administering contests, and we developed code to run it. We’ve now had hundreds of these contests and have yet to repeat a theme!

A contest devoted to fabric designs was novel, and from the beginning it attracted talented aspiring and experienced designers from all over. Because the voting in Spoonflower contests was open to anyone, it exposed the work of the entrants to lots of new people, some of whom created accounts, “favorited” the designs they liked, left nice comments, bought yardage in our Marketplace (our onsite shop), or kindly shared the fabrics and artists they discovered through social media. Artists like Deborah van de Leijgraaf (bora), a young mom and former art student from the Netherlands, and Samarra Khaja (sammyk), another young mother and graphic artist who lived in New York, began to acquire fans and followers through the exposure they gained from winning Spoonflower contests. Many people used our contests as a creative challenge, such as Mathew and Matthea den Boer. At the beginning of 2011, this sleepless young couple in Toronto were in the midst of surviving their baby’s first year and decided to keep their creative juices alive by entering every Spoonflower contest—one per week—for twelve months. They came in 96th place in the first contest they entered in January. But over the long weeks of winter and spring, the two creatives began to master the art of fabric design. In the first week of August, they won their first contest, which had a coffee theme. They won another before December, when their long year of challenges came to a close.

Eventually, our little community began to attract some big-time attention. Fabric companies much larger than Spoonflower began to follow our contests and to mine the images on our site and on our Facebook and Flickr pages for promising talent. We never saw this as anything but a validation of the idea behind Spoonflower. Unlike a traditional fabric company or retailer we don’t have to worry about losing talent because our product, in the end, is not an aesthetic or a set of selected work, but a technology platform that can be used by anyone. We welcome you to try it, too!