PASSOVER WAS a very special occasion for me as a child. My big moment, in what often seemed an interminable reading of our Passover Haggadah, was reciting the Four Questions (first in English, then in Hebrew), each of which asked how this night was different from all other nights. To the four answers (this night is different because …) I could have offered a fifth—I got to drink Coca-Cola in those ceremonial moments when the adults downed glasses of wine.

In my family of the early 1960s, Coke was only available on special occasions, such as Passover, or at the Sabbath meals held at my mother’s parents’ house. Otherwise, we drank milk, water, or juice. That was it. But as a child, I of course never wondered how Coke achieved the status of a drink acceptable on this Jewish holiday where observance of kosher rules was so important. Not until I began researching the history of modern kosher food did I understand how this came about.

I quickly learned that other scholars had looked at how Coca-Cola became kosher and began with those sources. The standard account had a comforting narrative and a decisive ending. In 1935 Atlanta Orthodox rabbi Tobias Geffen interceded with Atlanta-based Coca-Cola as a result of inquiries from rabbis in other cities as to the kashrus (kosher status) of this popular drink. After careful investigation of its properties, Rabbi Geffen suggested a couple of changes in the drink’s composition that were accepted by Coke for a special Passover run of the product. Subsequently, as Marcie Cohen Ferris explains, “Observant Southern Jews breathed a sigh of relief” as they could both be kosher for Passover and still enjoy an “ice cold Coke.”1

The closer I looked, however, the more holes appeared in this reassuring tale. Documents from the Coca-Cola archives showed that Coke had received rabbinic endorsement in 1931, and from a rabbi based in Chicago. If this was so, then why did Rabbi Geffen get involved at all? Newspaper articles showed that controversy still swirled around Coke’s kosher status in the late 1950s, shortly before I began drinking it at my family’s annual Passover Seder. These discrepancies pointed to a far more interesting, and profound, process of certifying kosher Coke, one that not only involved this signature beverage but also exposed one of the major challenges for proponents of kosher food in the mid-twentieth century: how to integrate concepts rooted in centuries of Jewish tradition with modern food chemistry. The struggles over Coke’s kosher status involved not only the drink itself, but the terms under which modern foods’ kosher status should be evaluated, what was necessary to do so, and what kind of knowledge was needed to assess a manufacturer’s claim that its products did, indeed, satisfy the requirements of traditional Jewish law. In this, Rabbi Geffen had to overcome the resistance of rabbis for whom such scientific knowledge did not seem necessary to determine if Coke was indeed kosher.

It turned out that Coke, as one of the first iconic American foods to seek kosher certification, was a testing ground for how kosher law could change modern food—and how, in turn, modern food would change the practice of kosher law. The debates sparked by certification of Coke taught Jewish authorities that they needed to assimilate modern food chemistry and understand ever changing manufacturing methods to assess a product’s compliance with kosher law. While Rabbi Geffen limited his intervention to Coca-Cola, contemporaneous initiatives by Organized Kashrus Laboratories, and its creator, Abraham Goldstein, generated a broad effort to incorporate scientific knowledge into the kosher certification process. In the end, it was the dynamic engagement of rabbinic authorities and food companies that yielded kosher Coke and opened the door to the widespread expansion of kosher food in America.

OF COCA-COLA AND GLYCERIN

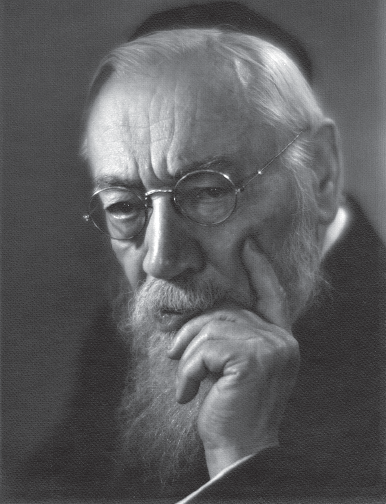

For Rabbi Geffen, the challenge of certifying Coca-Cola was only a small part of his service to preserving Judaism and strengthening observance among Jews. His unpublished memoirs do not mention this episode, instead dwelling on his many personal interventions to help Jews—ensuring the meat provided by local shochetim was in fact kosher, developing Hebrew education for local Jews, securing a get (religious divorce) for women whose husbands had left them, and aiding a Jew who had been shockingly sentenced to eight years on a Georgia chain gang. Geffen’s special role in the case of kosher Coke reflected his location in Atlanta and the wide respect in which he was held among the networks of Orthodox rabbis in the United States.

Born in Kovno, Lithuania, in 1870 (at that time part of Russia), Tobias Geffen came from a deeply religious family that sent him to the yeshiva in Slobodka, Lithuania, a prestigious institution of higher Jewish learning in Europe. After ordination, he studied with several of Lithuania’s leading rabbis before marrying and deciding to emigrate to America in 1903 following the Kishinev pogrom and the rise of anti-Semitic violence throughout Russia. After stays in New York City and Canton, Ohio, Geffen settled permanently in Atlanta in 1910. While his main responsibility was care of his congregation, Geffen was one of the few European-trained rabbis in the American South, with both his credentials and activities bringing him to the attention of Orthodox rabbis throughout the United States.

As he was the leading Orthodox rabbi in Atlanta, Coca-Cola’s headquarters, letters came to him from rabbis across the United States wanting to know if Coke conformed to Jewish dietary law. While Rabbi Geffen was not solely responsible for Coke’s eventual acceptance among observant Jews, he did correctly identify the main challenges. To determine Coke’s kashrus, he of course needed to learn what it contained—a subject jealously guarded by the company, eager indeed to keep its famed “secret ingredient” a secret. Promising complete confidentiality, Geffen obtained access to Coke’s manufacturing operations and had samples tested by impartial chemists.

FIGURE 2.1 Rabbi Tobias Geffen. Louis and Anna Geffen family papers, box OP11, Emory University Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library.

The main problems turned out to be alcohol and an odd trace ingredient called glycerin. Coke used alcohol in the manufacturing process, though there was no residue left in the final drink. During most of the year this would not have posed a problem for observant households; but Passover was special. Grain provided the source for the alcohol, thereby violating the Passover rule against eating leavened bread during that special week. Drinking Coke that used grain alcohol in the processing stage was as unacceptable on Passover as placing a loaf of bread on the table. Fortunately it was not difficult for Coke’s manufacturers to obtain alcohol from fermented molasses, thereby addressing one of Geffen’s objections.

Glycerin posed a much more intractable problem. Essentially an industrial by-product, glycerin assumes independent existence during the processing of fatty oils for soap. It is simply the predominant chemical left in the residue created after the soap is extracted. In Geffen’s view, glycerin’s kosher status depended on the oil from which it came—and most of the oil used to create it was derived from animal sources, livestock bones, fats, and other parts unacceptable for food consumption. In the late nineteenth century large packinghouses developed rendering operations that boiled inedible parts into a viscous liquid sold to soap manufacturers. Such efficient use of by-products was a source of profit and also reduced the volume of foul refuse extruded from these plants. As kosher-slaughtered animals comprised only a small proportion of animals killed in a plant, it was not economical for the company to separate their bones from the body parts of nonkosher carcasses. Given this industrial practice, Geffen concluded that glycerin was treif.

But it was present in Coke in only minute quantities, less than 0.01 percent. Did such a minor ingredient necessarily make Coke treif? Kosher law, in fact, contained a permissive set of rules known as bitul (nullification) that held out the possibility that the glycerin in Coke could be considered batul—nullified—as it was such a small quantity in a large mixture. Under traditional kosher law, bitul provides that when a small amount of a nonkosher ingredient accidentally ends up in a mixture its kashrus is not affected. As the most prevalent cases of bitul apply when the offending ingredient is no more than one-sixtieth of the mixture and does not affect it materially (known as bitul b’shishim), its intent was to address simple mistakes in the kitchen. Could such a concept apply to Coke?

With careful reference to traditional Jewish law, Geffen ruled that glycerin did not qualify for the bitul exemption. Basing his opinion on a ruling by the twelfth-century French rabbi Samuel ben Meir (known as the Rashbah) and the endorsement of this ruling by Moses Isserles in the sixteenth-century Yoreh De’ah, Geffen held that bitul applied only in cases where the mixing of troubling chemicals “was accidental, fortuitous, or unpremeditated.” Because the addition of glycerin was “normal procedure” and essential to Coke’s manufacture, the resulting mixture was treif. For these reasons Geffen held that Coke was not kosher.2

Glycerin’s widespread use in processed foods and beverages made determination of its status an issue that affected many more products than simply Coke. Since it has never aroused controversy (except among observant Jews!), glycerin’s role in our food system is not well known. Glycerin is hygroscopic, hungry for water or other liquids, and slightly sweet and syrupy at room temperature. With these qualities, glycerin permeates our foods, makes sliced bread stay fresh and cakes remain moist and crumbly—as well as keeping antifreeze and our car windshield washer fluids from freezing! In fact, a 1945 book on glycerin listed over fifteen hundred uses for this amazing chemical. Its kosher status thus posed enormous challenges for food companies using it in a wide array of products.3

Coke, it seemed, could not do without glycerin—though glycerin certainly was not its famed secret ingredient. Indeed, as glycerin “finds wide employment in the preparation of base extracts for flavoring purposes,”4 it is most likely that Coke’s secret concoction was dissolved into a glycerin solution so that the taste would diffuse evenly through the syrup shipped to bottling plants. And Coke was not alone in its dilemma: all soft drink manufacturers, indeed all food manufacturers that relied on bottled flavors, had traces of glycerin in their products.

Geffen may have realized that a lot was at stake with his decision on glycerin. At issue were not only the kosher status of Coke and other products containing glycerin, but, even more, the application of bitul to all modern processed food. If glycerin could be nullified under the principle of bitul b’shishim, what other substances could attain the same exemption? Might this create an avenue for loosening kosher requirements for other ingredients that were present in foods in minuscule quantities? Fundamental questions of kosher law and modern food were at stake.

Geffen’s teshuva (ruling) reflected a stringent application of kosher law. Plausibly he could have ruled differently, since glycerin did not impart any noticeable taste to Coke and comprised far less than one-sixtieth of its volume. By those measures, Geffen could instead have held that the principle of bitul b’shishim did apply and that glycerin’s presence was thus irrelevant to Coke’s kashrus. Instead, Geffen looked at processing methods and deduced that glycerin’s importance in processing meant its kashrus was in play. By doing so he endorsed the integration of modern scientific knowledge into kosher law—and created a kosher headache for food manufacturers.

Cottonseed oil offered a fortuitous solution for the problem of nonkosher glycerin. Since it was a vegetable product, it could serve as source for kosher glycerin. Cottonseed oil production grew steadily throughout the South in the early twentieth century as a shortening that offered an alternative to butter and lard, with firms such as Procter & Gamble and Lever Brothers developing vegetable oils for home use under the brand names Crisco and Spry. Procter & Gamble already supplied Coke with glycerin, so with Coke’s considerable leverage the company agreed to refine a special batch of cottonseed oil–derived glycerin to create kosher Coke. Rabbi Geffen inspected the factory making vegetable glycerin in July 1934; satisfied, he placed his “seal on the drums containing this ingredient.” With acceptable glycerin and alcohol secured, the rabbi issued his famous teshuva in time for Passover in 1935. In subsequent years he relied on affidavits from Proctor & Gamble executives to ensure that the glycerin used in Coke “was made from vegetable sources and no animal fat.”5

This is where our happy story should end, with American Jews reassured by Rabbi Geffen’s hecksher (endorsement) on Coke bottle caps that they could now drink Coke on Passover. And indeed, when it came to Coke, all seemed fine—at least for the next twenty years. But the extension of Rabbi Geffen’s ruling was another matter; Coke was hardly the only processed food attracting the attention of observant Jews. Rabbi Geffen did not become involved further determining the kosher status of other processed products; that initiative fell to a lay Jew whose efforts would provide the underpinnings of American kosher certification organizations.

THE INVISIBLE CHEMIST

Parallel to Geffen’s involvement with Coke, a more comprehensive attempt to apply chemical knowledge to kosher certification was taking shape in New York City under the leadership of Abraham Goldstein. A devout Orthodox Jew and a chemist by trade, Goldstein appreciated the complex challenges of certifying kosher food long before many rabbis whose knowledge of kosher law was rooted in foods made in nonindustrial settings. Deeply concerned that Jews would stray from the religious practice of kashrus because of modern food’s allure, Goldstein devoted his life to strengthening the capacity of Jewish organizations to enforce kosher law. While not alone in his efforts, Goldstein was distinguished by the degree of his devotion to seeing chemical knowledge incorporated into the practice of kosher certification.

Goldstein’s activities are utterly absent from the official Orthodox accounts of the origins of kosher certification in America. The documentary evidence makes abundantly clear that he was the principal architect of the Orthodox Congregation’s (later the Orthodox Union) kosher certification program in the 1920s and 1930s. A member of its executive committee, he was the first person to bring charges against food vendors who violated New York State’s kosher food regulations; OU sources also credit Goldstein with devising its strategy of certifying national firms who sought to sell kosher food. He negotiated the first such agreement with Heinz foods in 1923 and oversaw the creation of the famous U within a circle symbol for its use. As he later recalled, the company “thought it impossible to use the insignia of the Union, which had ‘Kosher’ in Hebrew letters.” By 1929 he had cemented agreements with several other firms including the Loose-Wiles Sunshine Biscuit Company, Sheffield’s dairy products, Duggan’s breads and cakes, and the Jaburg Brothers’ vegetable fat company.6

Yet his name does not appear anywhere on the Orthodox Union website, nor in accounts of its history. The most egregious erasure of Goldstein’s role takes place in the Orthodox Union’s official history, published in 1997 by longtime staff member Saul Bernstein. Drawing from the same documents I perused, Bernstein overlooked the references to Goldstein as chair of the OU’s Kashrus Committee, the accolades he received in speeches delivered at OU conventions, and his official position as the OU’s chemical expert.7 These silences about Goldstein’s role more than fifty years after his death reflect both the controversies he provoked and the deep emotions he aroused in his efforts to integrate scientific knowledge with traditional Jewish law.

It took information supplied by his grandson and great-grandson to fill in important details of his life. Born in 1861, Abraham Goldstein was raised in East Prussia, at the time part of Germany, just south of Lithuania and its great center of Jewish knowledge, Vilna. He was a well-educated man before he joined the enormous wave of Jewish immigration to America in the late nineteenth century. While it is unclear how Goldstein learned chemistry, Germany was the center of this emerging scientific field, and there would have been abundant opportunities for him to do so. He arrived in New York in 1891 and, after brief sojourns in Baltimore and New Jersey, settled in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan where he pursued various opportunities using his training as a chemist. A devout man, he tried to work with the Agudath Harabonim (the Union of Orthodox Rabbis, an association of European-born rabbis) to improve kashrus standards in New York and participated in successful efforts to pass legislation in the 1910s that brought kosher food under state regulation.

FIGURE 2.2 Abraham Goldstein (sitting) with daughters (left to right) Clare, Sarah, and Rebecca. Courtesy Ezra and Monica Friedman collection.

It was only in the early 1920s, following many years of efforts to improve kosher standards, that Goldstein shifted his considerable energies to the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations, a New York–based network of Orthodox synagogues seeking to create a central organization for the Orthodox strand of Judaism throughout America. After a decade of behind-the-scenes efforts with food manufacturers, Goldstein tried to reach out to observant consumers in the early 1930s by starting a “Kashruth Column” in the Orthodox Union, the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregation’s monthly magazine. Billed as the Rabbinical Council’s “chemical expert,” Goldstein provided concrete answers to questions about particular products, and offered to investigate when he did not know the answer.8 The magazine’s small circulation limited the column’s effectiveness; usually questions from only six or so letters were addressed in each. Soon Goldstein would find a better vehicle for reaching observant Jewish consumers.

Disagreements between Goldstein and Orthodox rabbis over the role of science in kosher certification simmered throughout the 1920s and early 1930s and came into public view shortly after he founded the Organized Kashrus (OK) Laboratories in 1935. Constituted formally as an organization to advise rabbis on food science, OK’s free English-language journal, the Kosher Food Guide, gave Goldstein a platform to make his views widely known in Jewish circles. The first sentence in its March 1935 opening editorial was a clarion call for the importance of scientific knowledge in kosher certification. “The rapid changes in the process of manufacturing of new articles of foods,” he declared, “made it necessary to investigate the ingredients contained therein as well as the method of fabricating to ascertain if they do not contain trefa [treif] substances in itself or come into contact with such during the process of manufacturing.” Accompanying his robust appeal was a warning that rabbinic authorities previously had not appreciated this need. He wrote that in the past “such investigations were unfortunately not entrusted to chemists,” with the result that rabbis “were misled to state that the article in question conform[ed] to the Jewish Dietary Laws.” To the “opposition to our work,” he affirmed that in fact the same end was served, the expansion of kosher food options “in a variety equal to non-Kosher food” such as “to strengthen Judaism.”9

The Kosher Food Guide offered comprehensive lists of kosher food products as well as articles on kashrus issues Goldstein deemed important. As the most comprehensive source of information on kosher-certified food, the publication was extremely popular among observant Jews; in 1938 Goldstein noted that he received thirty to forty letters daily regarding the kashrus of particular products. With its focus on science, and its offer to serve as a chemical laboratory that could test food provided by any rabbi, Goldstein forced the issue of the relationship between modern food science and traditional kosher law. And, with his platform, he aggressively criticized rabbis who, in his opinion, had placed their hecksher on food products without making sufficient effort to understand their underlying chemical composition.

WORRIED KOSHER CONSUMERS SPEAK OUT

To establish a dialogue with the observant Jewish public in the pages of the Kosher Food Guide, Goldstein started a column called “Questions and Answers” modeled on his “Kashruth Column” in the Orthodox Union. Unlike the Orthodox Union journal, however, the Kosher Food Guide was a widely distributed publication funded principally by advertising whose circulation quickly rose from 50,000 to 150,000 copies of each quarterly issue. The popularity of the guide’s “Questions and Answers” column was apparent in the torrent of letters sent to it from all over North America. The January 1937 issue plaintively noted that over twenty pages of questions had to be omitted due to space limitations. In a column published a year later, Goldstein answered forty-six letters sent from Toledo, Baltimore, Detroit, Philadelphia, Tulsa, Burlington (Vermont), Jessup (Pennsylvania), Carlsbad Springs (Ontario), and Atlantic City, as well as New York City. Some correspondents wrote several times, such as Mrs. M. Evans in Corsicana, Texas, who wanted to know if Gold Dust cleanser was kosher (after writing the manufacturer, Goldstein determined that it was not).

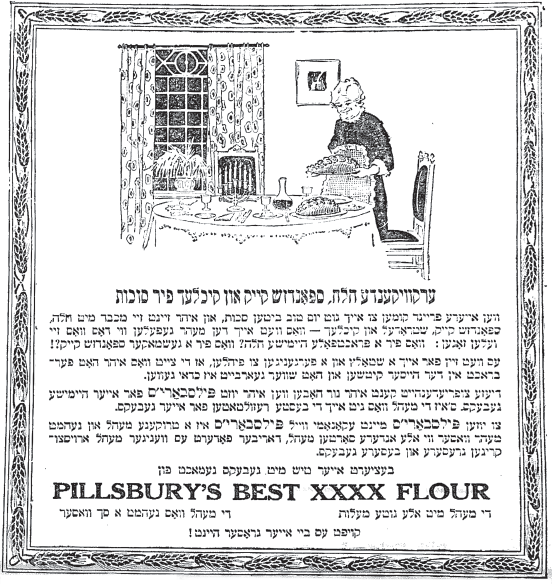

The correspondence with Goldstein indicates that concern over Coke’s kosher status was part of a larger phenomenon: observant Jews’ desire to sample the packaged foods carried by the new retail food chains such as A&P. Jews continued to patronize shops operated by coreligionists, especially for fresh items such as beef, chicken, and bread, but increasingly visited the chain stores to see what new foods were available. Women were not yet replacing home-cooked meals with convenience goods; instead, they were seeking to understand which of the new packaged goods were permissible under kosher law.

FIGURE 2.3 “Refreshing hallah, sponge cake, and cookies for Sukkos.” Advertisement for Pillsbury Best XXXX Flour, Americaner, October 18, 1919, 20. Collection of Shulamith Z. Berger, courtesy National Library of Israel, Jerusalem.

Worries about popular brands indicate the impact of chain stores on shopping patterns. Mrs. A. D. Simpson of Brooklyn, New York asked whether “White Rose Products canned, in jars, or bottles” were kosher, as did Mrs. R. J. Kalfen of Perth Amboy, New Jersey, the latter also inquiring about Campbell’s soups. Many questions concerned Ann Page products, A&P’s private label, such as those from Mr. S. Applebaum, who asked about the entire line. “Your question is too general,” Goldstein replied to his query “as there are Kosher and trefa products packaged under this trade name.”10 Befitting his care with kosher certification, Goldstein asked for identification of specific products before offering an opinion.

The longer letters indicate what observant Jews were seeing on store shelves and probably including in their families’ diets. Mrs. J. Finkelstein from Cleveland wanted to know if Kellogg and Ralston cereals were acceptable (they were), whether Crisco and Spry shortenings could be used for cooking (they could), whether paprika and vanilla could be added to food (under some conditions), if Kraft’s Miracle Whip and A&P ketchup could go onto sandwiches (yes), and whether Hershey Chocolate Syrup and A&P fruit cocktails could be included with desert (both were acceptable, though Goldstein warned that some Hershey chocolates contained milk). Mrs. William Packer from Brooklyn worried if the Zwieback crackers, lady fingers, cereal, and canned vegetables that she was feeding her baby were kosher for Passover. Goldstein kindly advised Mrs. Packer that these items were not, recommending using matzoh meal instead and steaming her own vegetables. He admitted that perhaps these would be “tedious” to make, “but what mother minds a little work for her baby.”11

Goldstein’s positive responses to Mrs. Finkelstein were unusual; more often his correspondents were disappointed by what they learned from him about popular products. Treif ingredients ruled out Gerber baby food, Kraft Velveeta and American cheese, most white breads including Wonder Bread, and popular crackers such as Ritz, Graham, and Uneeda. Some flours, a few brands of ice cream, and most varieties of peanut butter were acceptable, as was Aunt Jemima pancake mix. Wrigley’s chewing gum and Milky Way candy bars were kosher; but Dentyne gum and Baby Ruth bars were not. Goldstein moderated these disappointments by offering alternatives such as Dugan’s baked goods (including their white bread), Loose-Wiles Sunshine crackers, Reid’s Kosher Ice Cream, and the Heinz line of canned goods (including baby foods), as well as the foods made by Jewish companies such as Rokeach and Manischewitz. To Jews interested in Italian and Chinese foods, he was able to find kosher suppliers, recommending Skinner’s macaroni to Mrs. B. Fasman in Oklahoma and Toy Fong Chow Mein noodles to Mrs. D. Coplan in Pennsylvania.

The simple questions contained in these letters communicated the worries and frustrations of observant Jews seeking food for their family to eat at home or to enjoy in a public place. Much as they might want to buy the same food as Christian Americans, observant Jews realized that many appealing products did not comply with the requirements of their religion. They could look, but dared not touch. The emotional conflict between longing for and resentment of these products must have been enormous, especially for the families whose children might want a treat at Coney Island or a soda at a baseball game.

Frequently glycerin was the problematic ingredient, as small amounts appeared in many products. Goldstein warned that flavorings for ice cream and soda drinks often contained glycerin and that vanilla extract and almond paste, commonly used in baked goods, similarly “very often contain glycerine.” Glycerin was a huge problem for popular candies; Goldstein advised that “licorice candy very often contains glycerine” and that candies manufactured by Schraft’s, Barricini, and Fanny Farmer included many “where glycerine might be used.” He also worried that, with the incessant changes in production methods, glycerin was showing up in more and more foods, such as the new artificial sausage casings that were reaching the market in the mid-1930s.12

Glycerin’s use in nonfood products created challenges as well. Mrs. E. Ackerman in Brooklyn learned that “some lipsticks contain glycerine,” and, since glycerin coated many varieties of cellophane, Mr. R. Neuman was advised to “taste the cellophane paper. If it is sweet, glycerine has been used.” Even cleaning one’s teeth was worrisome. “Most dentrifices are prepared with glycerine,” Goldstein informed Mrs. Naomi Klein in Richmond Hills, New York, and he told Mr. A. M. Feier that “most toothpastes contain glycerine.” An observant Jew could not get a breakfast muffin, a sandwich, an ice cream cone, a candy snack, or even brush his teeth without encountering glycerin.13

Glycerin’s importance was such that its kashrus was the very first controversy addressed by Goldstein in the Kosher Food Guide. In its second issue (published at the same time as Geffen’s negotiations with Coke), he critiqued a lengthy memo by an unnamed author that contended glycerin could be kosher even if derived from nonkosher oils. The essay, originating from an unidentified firm that made glycerin, argued that glycerin was not actually in the oil from which it was derived, since it was only formed after a strong “chemical action.” Hence the author concluded that glycerin drawn from either meat or vegetable sources was kosher.

Goldstein made short work of this argument. His riposte was straightforward: a food’s kashrus depended on the material from which it was drawn—the same position as Rabbi Geffen. Glycerin intrinsically was neither treif nor kosher; what mattered was its source. And he ridiculed the unnamed author, pointing out that with his argument “lard could be Kosher, because it is not in the pig as lard. Only when it is subjected to a great heat it separates out as lard.” For this reason, Goldstein viewed all foods that contained glycerin as treif, including Coca-Cola.14

Coke’s kashrus (along with Pepsi’s status) was the subject of repeated queries. The problem, very simply, was that “Coca Cola is made with glycerine,” Goldstein warned Mr. Saul Weberman in April 1937. In 1939 Goldstein repeated this warning to Mr. L. Levy in Baltimore, and in 1942 to Mr. M. Schreiber in Philadelphia. Sounding weary, after responding to dozens of letters on this topic, in June 1943 Goldstein wrote Miss Elaine Weiss that “there has been nothing new discovered in regard to Pepsi-Cola and Coca-Cola. We still maintain that both these products contain glycerine.”15

Goldstein was unmoved by Geffen’s endorsement of Coke’s special Passover concoction, though he avoided explicit criticism of the rabbi. He told Dr. Maurice Appel in 1938, “The hechsher given by the Rabbi you mention in your letter does not alter the facts in this case. As we ourselves do not drink Coca-Cola during the year, we certainly would not drink it on Passover.” In a longer essay on the continuing challenge of glycerin in processed food, he indirectly criticized Geffen’s method of relying on Procter & Gamble statements to certify the glycerin used in Coke. Goldstein declared that “the issuance of affidavits” (a reference to the documents obtained by Geffen from Procter & Gamble) “stating that only pure vegetable oils have been used does not deserve any credence.” Goldstein probably was not aware that Rabbi Geffen had personally inspected the Proctor & Gamble factory in 1934 and thus had satisfied for himself that there was no improper taste transfer between treif and kosher glycerin during processing.16

FIGURE 2.4 Coca-Cola advertised extensively in popular Yiddish newspapers. In this one, Yiddish text on the awning reads, “Drink Coca Cola in Bottles.” Morgen Journal, July 21, 1922, 3. Collection of Shulamith Z. Berger, courtesy National Library of Israel, Jerusalem.

The principal target of Goldstein’s ire, however, was not Rabbi Geffen, but instead the first rabbi to issue a hecksher for Coke, Rabbi Shmuel Aaron Levi Pardes (1887–1956), editor of the influential Hebrew-language rabbinic journal Ha-Pardes. What Goldstein did not know is that in private Geffen had waged a strong campaign against Pardes and the very same practices that Goldstein found objectionable.

In the 1930s Pardes was one of the nation’s most prominent Orthodox rabbis. Born and educated in Poland where he established Ha-Pardes in 1913, Pardes moved to America in 1924 and settled in Chicago in 1927, where he reestablished the journal. It became the unofficial voice of the Agudath Harabonim. To finance the journal, Pardes accepted advertising from manufacturers whose products he certified as kosher, issuing a hecksher for a fee—and thereby generating a rather glaring conflict of interest.

Coca-Cola began advertising in Ha-Pardes in 1931. In March Pardes issued a teshuva, an official statement certifying Coke as kosher. In it he explained that he had visited Coke’s Atlanta plant, where he learned about the “secret ingredients” in the drink. After investigating Coke’s contents “from beginning to end,” he declared that “everything is KOSHER according to the Jewish law, and this is a drink which is permissible for all Israel to drink.” But, without any training in chemistry, and based on no more information than a visual inspection of the Cola-Cola plant, Pardes was not in a position to make such an authoritative statement.17

While Goldstein would become Pardes’s most vocal critic, Rabbi Geffen was equally an opponent of Pardes’s approach to kosher certification. Indeed, it seems that Geffen’s decision to intervene in the certification of Coke was a deliberate effort to curtail Pardes’s influence. Geffen had been profoundly concerned with Coke’s kashrus since at least February 1927, when Abraham Nachman Schwartz wrote him with information supplied by Baltimore butcher David Chertkoff that Coca-Cola used glycerin, a fat “made of the refuse of things that are impure and prohibited.” Startled by this disturbing report, Rabbi Geffen asked Georgia’s state chemist to analyze Coke’s contents. In May he learned, certainly to his dismay, that the allegation was true; the chemist certified that Coca-Cola contained 0.09 percent glycerin. At some point between then and 1932, Rabbi Geffen personally inspected Atlanta’s Coca-Cola plant and confirmed that the drink did indeed contain glycerin.18

With this information, Rabbi Geffen must have been deeply disturbed by Pardes’s unconditional endorsement of Coke along with the news that he had come to Atlanta and inspected the Coke facility without involving Geffen, Atlanta’s leading Orthodox rabbi—a profound breach of rabbinic etiquette. Soon Geffen could see advertisements for kosher Coca-Cola in other newspapers, where local rabbis added their endorsement to the drink that was bottled in their area. Rabbi Morris N. Taxon certified Coke in Memphis, as did Rabbi Hersch Kohn in New York City; the national Hebrew-language weekly HaDoar carried Pardes endorsement as well as a message, “Rejoice in your festival with Coca Cola.” Knowing that this so-called kosher Coke contained glycerin derived at least in part from pig fat, Rabbi Geffen planned carefully how to counter the claims of a far more prominent national rabbinic leader.19

Geffen first confronted Pardes privately by writing a series of letters in 1931 challenging Coke’s certification. While those letters have not survived, Pardes’s angry retorts have, and they illustrate the profound nature of Geffen’s challenge. He accused Geffen of being the only rabbi to doubt Coke, as “there are currently rabbis all over the country who say it is kosher.” And he asserted there was no glycerin in Coke, based on affidavits from Coke’s Chicago chemist and the head of its Chicago operations, the latter promising Pardes “he would give me the whole factory” if Coke did indeed contain this troubling ingredient.20

Since Pardes would not budge, Geffen began to correspond with other Orthodox rabbis, expressing his doubts about Coke. In doing so, Rabbi Geffen could draw on the long rabbinic tradition that accorded primacy to the opinion of the rabbi who resided in the place where a questionable product originated. These letters had a dramatic impact. Many wrote to Pardes demanding an explanation, leading him to complain to Geffen that “there are now letters from all of the rabbis who provided kosher certification for Passover.” Rabbi Hersch Kohn wrote to Geffen directly, apologizing for his acceptance of Pardes’s certification and taking responsibility for his error. “I did not truly know,” he explained, “that there was in there, in Atlanta, so great and distinguished rabbi as himself, and if I had known that before, I would have addressed your scholarliness in the first place, because I, for my part, did not go to the boundaries of investigating the opinion.” Indeed, the great volume of letters sent to Geffen provoked him to issue his teshuva, as “it was very difficult for me to answer each of these inquiries.” Geffen doubtless privately conveyed this furor to the Coca-Cola company and the value of making the changes he requested in Coke’s chemistry so that none of this became public and impacted Coke’s image.21

Rabbi Geffen kept the controversy as quiet as he could, even as he moved decisively—and successfully—against Pardes. But Geffen’s intervention stopped here, his principal objective achieved; he was not inclined to extend the dispute into wider Jewish circles. Temperamentally, Abraham Goldstein had none of Geffen’s circumspection. In the pages of the Kosher Food Guide he alleged publicly that the monthly advertisements from Coke and the fees garnered from issuing the hecksher had influenced Pardes’s judgment. “Such men undermine the very foundation of our religion,” he thundered. “There is no room for such scoundrels in decent company.” Goldstein also had no leverage other than public exposure of practices he thought violated Jewish law. Since he was, by his own admission, “neither a rabbi nor the son of a rabbi,” Pardes would not deign to debate him. Cloaked in his authority as a rabbi and editor of a leading rabbinic journal, Pardes continued accepting advertisements from companies he certified—and that offered even more controversial products.22

THE IMPROBABLE “JUNKET” CONTROVERSY

The heated arguments over glycerin paled next to the vehemence of the exchanges over rennet, an enzyme used in cheese manufacturing that typically came from a calf’s fourth stomach. The origins of this explosive debate went back to 1926, when Goldstein (as the OU’s representative) met with executives of the Hansen Laboratory to ascertain the kosher status of Junket, a powdery product that, when added to milk, created custardlike deserts. The company offered six flavors and aggressively marketed the product to mothers whose babies resisted drinking milk. The rennet that gave Junket its coagulating quality came from calves that were not kosher slaughtered. Nonetheless, the company claimed the product was kosher—because the offending rennet disappeared when the mixture transformed into a thick custard. Goldstein rejected their claim, taking the same position he would later articulate with regard to glycerin—that anything taken from a treif source remained treif. Over his objections, the company secured kosher certification from Rabbi Pardes and, similar to Coke, began advertising in Ha-Pardes trumpeting the claim that it was “kosher without any fear or doubt.” Hansen Laboratories also bought large advertisements in Jewish papers and even launched a radio campaign that featured music sung by an Orthodox cantor.23

In 1936, with the Kosher Food Guide as his platform, Goldstein opened a withering assault on Pardes’s certification of Junket. His adversary responded in kind with articles in his Hebrew language publication and by securing the Orthodox Union’s backing for Junket (and leading to Hansen Laboratories placing advertisements in the OU’s journal). This “cause célèbre” over an obscure product even spilled overseas, as Goldstein and Pardes wrote to influential European rabbis to secure their support.

Goldstein’s diatribes on rennet were interspersed with further commentaries on glycerin, because to the chemist they presented the same challenge: how to track modern food production’s introduction of treif ingredients into supposedly kosher food. Since rennet and glycerin had as their source animals that were not kosher, in his view nothing containing those chemicals could be kosher. With this argument, Goldstein made a critical claim (one that paralleled Rabbi Geffen’s opinion): that bitul (nullification) could not take place with rennet, glycerin, or indeed any chemical derived from a nonkosher source that played an essential role manufacturing a particular food. His passion and unyielding language on the subject reflected a scientist’s view that an essential principle of kosher law was at stake, even as he granted that Junket, in itself, “is of very small importance to the Jewish community.”24

What worried—and infuriated—Goldstein was the blithe disregard for scientific knowledge in Pardes’s and the OU’s endorsements. They do not have the “ability to find anything in regard to the question of Junket,” he declared, “because they do not know the least thing about the Chemistry of the article.” He relied on food science, for example, to refute one of Pardes’s defenses that the rennet could become batul because the company needed to add salt, sugar, flavors, and muriatic acid to it before it was effective. This was an important claim under kosher law; if indeed the rennet was not an active ingredient, the principal of bitul b’shishim would allow it to be nullified, as it comprised far less than one-sixtieth of the final product. And, if this was the case, Junket was kosher. Goldstein ridiculed this argument as one no rabbi would make if he were “acquainted with a chemist familiar with Dairy products.” Meat processing companies added salt, muriatic acid, and occasionally boracic acid to the stomach, he explained, as part of a curing process to prevent its deterioration before extracting the rennet; those ingredients did not contribute to rennet’s subsequent coagulating effect on milk. Since it was rennet, and rennet alone, that affected the milk, it was essential to the final product, just as glycerin was for Coca-Cola; hence it could not be nullified, and, similar to Coke, the final product was treif.25

Pardes’s endorsement, however, rested as well on another element of kosher law—that the processing of the rennet had eliminated its treif origins entirely; thus the product was kosher to begin with! By making this startling claim, Pardes actually was following an accepted method of isolating a concept discussed in rabbinic commentaries and extending it to new situations. In principle, his approach was entirely, well, orthodox; but his conclusions had profound implications for kosher certification.

His source was impeccable—the opinions of the Rama, Rabbi Moses Isserles. Pardes made much of one of the Rama’s rulings that when an animal’s stomach was dried as hard as wood, milk could be carried in it as no taste or flavor would transfer. The Rama was concerned with a common practice in early modern agricultural communities of placing milk within dried calves’ stomachs to create cheese, and whether doing so created the prohibited mixture b’sar bacholov, combining meat and milk in violation of the admonition in Deuteronomy 14:21, “You shall not boil a kid in its mother’s milk.” In considering this issue, the Rama assumed that both the milk and rennet came from kosher animals and that the stomach remained in a dried state throughout the process. Since the stomach used for this practice was dry, the Rama ruled that no flavor would transfer; hence an improper mixture did not result. With this precedent, Pardes contended that the Rama’s comments supported his hecksher, and his argument that Junket was kosher, since the “taste” of the dried, powdered rennet added to milk did not transfer to the final product.

The notion of “flavor transfer” used by the Rama and Pardes translates roughly as b’lios and is a core concept of kosher law. “Under certain circumstances,” Rabbi Zushe Yosef Blech explains in his exhaustive volume Kosher Food Production, “contact between two foods allows for transfer of flavor between them.”26 As developed over centuries, b’lios is a complicated concept whose application varies widely depending on the materials in question. While there were many iterations of rabbinic opinion, there was wide agreement that dry and hard materials posed much less of a problem than warm and wet ones. The core issue remained the transfer of flavor from one to the other, and physical properties largely determined what was likely to take place. Indeed, the Rama was not alone in suggesting that once a material was “dry as wood”—as the operative phrase usually read—it would not affect the kashrus of other foods; Pardes thus had reason to believe that he was on firm ground with his ruling.

Pardes rested his claim on European production methods “where rennet powder has been manufactured for the last 50 years.” Missing from Pardes’s assessment was an awareness of how industrial meatpacking operations in the 1930s bore little resemblance to those he referenced. Twentieth-century processing operations extracted rennet from stomachs that were neither dry nor kosher. An authoritative 1927 account explained that stomachs destined to yield rennet for cheese manufacturing were “held in a dry condition until needed for use, the juices [e.g., rennet] being extracted by placing [the stomachs] in a water solution.” Drying thus only preserved the stomach until there was a need to remove the rennet, and which took place through a liquid process. Since the stomach was moist when used to supply rennet, and the rennet came from nonkosher animals, Goldstein argued that the Rama’s commentary did not provide support for Pardes’s certification. To him, it was yet another example of how traditional Jewish law could only be applied to current kashrus issues by incorporating knowledge of contemporary food production methods.27

Goldstein’s quarrel with Pardes was part of a larger argument over the place of science in kosher certification and, with that, the role of lay Jews in this process. Under Jewish law, rabbis alone had the authority to issue a hecksher declaring a product kosher and only other rabbis could dissent from his decision once made. After Goldstein established his own journal, he had his own voice, and his dissenting opinions angered the Orthodox rabbinic hierarchy, which was offended by the presumption of a lay Jew questioning their judgment and, by implication, their authority.

By the late 1930s, leading Orthodox rabbis had lost patience with Goldstein. Pardes doubtless reflected sentiment among his peers when he complained to Hungarian rabbi David Schlussel, “Your honorable Reverend has thrown his letter to common men who constantly shame learned educated men,” after Rabbi Schlussel had responded favorably to Goldstein’s query regarding rennet. Asking Pardes in print, “How much money has been paid for this false Hecksher,” or the OU if any of its members “participated in the division of this money,” did not help the tenor of the debate. The Rabbinical Council of the Orthodox Union backed Pardes and demanded that Goldstein submit Kosher Food Guide issues for rabbinic review before publication. When Goldstein refused, the OU went so far as to rewrite the minutes of its March 1936 executive council meeting to imply he had reneged on such an agreement when there was in fact no record of Goldstein accepting this requirement.28

Goldstein’s claim to superior knowledge, along with his open defiance of rabbinic authorities, led to, in effect, his excommunication from the Orthodox wing of organized Judaism. The sordid episode climaxed when a rabbinic court of Orthodox rabbis issued a proclamation that improbably branded Goldstein “a thorough ignoramus in matters Jewish” and complained that he “has impudently assumed authority to decide in matters of kashrus” thereby “assuming the authority of a rabbi.” For these transgressions the court pronounced “the unreliability of this individual in relation to kashruth,” and directed Jews “to pay no heed to the O.K. pamphlet.” Seeking to isolate Goldstein, the declaration went to rabbis and synagogues throughout New York City as well as to manufacturers that had advertised in the Kosher Food Guide. To a gentile business owner genuinely seeking to satisfy perplexing kosher requirements for his products, the conflict must have sounded like a bizarre jurisdictional dispute hardly befitting the religious authority claimed by Jewish organizations.29

GOLDSTEIN’S POSTHUMOUS VICTORY

Abraham Goldstein passed away at the end of 1944 with his publication and organization intact, but deeply embittered by the ostracism occasioned by the 1939 rabbinic proclamation. There is no evidence that advertisers withdrew from the Kosher Food Guide; indeed the listings it contained were far more extensive than in the competing guides published by the Orthodox Union. But during the remaining five years of his life there is also no indication that the Orthodox rabbinic hierarchy softened their stand toward him.

Within a few years, though, Goldstein’s views would be vindicated, along with his message to attend to scientific knowledge and the technicalities of food manufacturing systems. In 1952, with the support of many influential rabbis in Israel and the United States, leading Orthodox Rabbi Eliezer Silver proclaimed an issur (a ban) that declared Junket treif. Even though Silver was a member of the rabbinic court that had denounced Goldstein for his advocacy of the same position, there was no admission of the history behind the issur. Concerned Jews remembered nonetheless; Abraham’s son George Goldstein, now editor of the Kosher Food Guide, gloried in the decision, writing that “the layman who dared to tell the truth, and was shunted and pushed aside, is now proven to be right.” He could also express gratitude toward the hundreds of Jews who wrote to the journal in the decision’s aftermath thanking the Kosher Food Guide for its stands.30

Rabbi Silver’s reversal on rennet conceded (without admitting so) that lay knowledge was necessary to correctly define kosher requirements for contemporary foods. Rabbi Geffen had pioneered such a methodological shift in rabbinic circles in the 1920s and 1930s, and Abraham Goldstein had relentlessly argued for such an approach in the 1930s and 1940s. Finally, in the 1950s, the core institutions of Orthodox Judaism accepted the need to understand science and technology so as to effectively enforce kosher law. Ironically, doing so also brought Coke’s kosher status back under a close lens.

In 1957 a huge public controversy erupted over Coke’s kashrus. Glycerin was, yet again, the main issue. It turned out that the allegedly kosher glycerin supplied by Procter & Gamble was manufactured in the same plant, and on the same equipment, used to process nonkosher meat-based glycerin. Procter & Gamble could still provide affidavits certifying that the glycerin supplied for kosher Coke was made only from vegetable sources, and since they were unfamiliar with the concept of b’lios probably felt that they were in full compliance with kosher requirements—when in fact they were not. In an adept extension of b’lios from the home to the industrial factory, Rabbi Eliezer Silver (who broke the scandal) compared Procter & Gamble’s action to “frying ham in a skillet, and then placing kosher meat in the same skillet.” To satisfy the highly publicized complaints, Procter & Gamble constructed a parallel production line for vegetable-based glycerin at a cost of $30,000.31

Eighty-seven by this time, Geffen was not actively involved in Coca-Cola’s certification and could be forgiven for not clambering over the glycerin manufacturing operations he had inspected in 1934 as a much younger man. For many years he had received annual affidavits from Proctor & Gamble certifying that the glycerin supplied to Coke “was made from vegetable sources and from no animal fat.” However, Proctor & Gamble had never informed Geffen that it was now using different technology to refine glycerin, in all likelihood unaware that doing so created a new problem of b’lios.

When Geffen had first certified Coke, glycerin producers generally used a batch processing method where they emptied the entire contents of a railroad tank car into processing containers that cooked and filtered the liquids. The “special process” alluded to by Procter & Gamble probably referred to the segregation of cottonseed oil in these processing chambers, from which came the vegetable-based glycerin that went to Coke’s Atlanta plant. Fatty oil processors by the 1950s had developed a more efficient continuous-flow system where separate processing stages were connected by pipes, making complete segregation of a vegetable-based glycerin batch far more difficult to achieve. While the vegetable oil may have been processed in a separate tank, the common network of pipes conveying the glycerin output to successive processing stages meant that it came into contact with the meat-based product that had passed through the same pipes.32 To Procter & Gamble, glycerin production simply had been modernized, but to kosher certifiers the kashrus of this ingredient—and with it, all the products it went into—had been irretrievably compromised by the transfer of taste from treif materials.

The response by Coca-Cola and Proctor & Gamble was, nonetheless, consistent with their acceptance of kosher strictures two decades earlier. Their chemists probably found the uproar hard to understand; after all, there was absolutely no difference in the chemistry of vegetable-based product intended for kosher Coke and the meat-based glycerin that supposedly contaminated it. Yet they accepted the need to invest tens of thousands of dollars to accommodate Jewish religions requirements. Doubtless Rabbi Geffen and George Goldstein were in the end pleased by the outcome.

A great deal was necessary, therefore, for my family to feel comfortable letting me drink Coke on Passover. While fabrication of a kosher glycerin was critical to developing kosher Coke and kosher versions of processed foods, that accomplishment, however important, was not the most significant outcome of this episode. Even more fundamental was the consensus of rabbinic thought generated by the debate over glycerin’s kashrus (along with rennet) that modern food science and manufacturing methods needed to be understood to apply traditional kosher law in the modern era. Rabbi Silver’s decisive interventions aptly captured such acceptance, as he was one of Goldstein’s bitterest opponents but also a revered Orthodox rabbi whose opinions commanded deep respect among the most traditional segments of the Orthodox community.33

Glycerin was one of the early ingredients employed by food chemists to facilitate the creation of processed foods, and the agreement among Orthodox authorities on the importance of its origins had profound implications for other ingredients. Accepting as kosher foods containing glycerin under the concept of bitul would have established a loose kashrus principle applicable in theory to many food ingredients. Rennet’s importance was not principally in its effect on Junket’s kashrus (indeed the product soon faded from the marketplace), but as part of the same conceptual conundrum as glycerin. The eventual accord among Orthodox rabbis for a narrow interpretation of bitul and a stringent scientific inspection of all ingredients’ origins established a critical kashrus requirement for many postwar packaged food products. Similarly, enforcement of the principle of b’lios in manufacturing operations would have an enormous impact on the requirements for manufacturers wishing to secure kosher status for their goods. Kosher certification of processed food was still in its infancy in 1960, but the process through which Coke had become kosher augured well for the future development of modern food acceptable to observant Jews.34

Far greater challenges, however, lay ahead, with the emergence of many packaged foods in whose contents lurked a multitude of ingredients unknown to the sages of Jewish law. Cake mixes, frozen dinners, and other easy-to-make foods spread in the 1950s and 1960s as food preparation time shrank in American homes. Observant Jewish homemakers naturally wanted to make use of these new and wonderful products, but they also had to worry whether they were kosher. Ironically, a critical battle affecting all these foods erupted around a seemingly innocuous if ubiquitous dessert—Jell-O—that was one of the first packaged “convenience” foods.