OUR ANNUAL Passover Seder was, as for most Jewish families, an opportunity to eat traditional food, retell the story of Jewish liberation from oppression, and, for grown-ups, to drink the required four glasses of wine as well as other celebratory beverages. But as the children reveled in the special opportunity to guzzle Coca-Cola, my father could not restrain his disdain at the sweet kosher wine, usually Manischewitz, that seemed mandatory for the occasion. As he grew more successful in business in the 1960s and 1970s, he developed a taste for fine French wine. While he was not troubled about drinking nonkosher varieties while eating out, Passover was about Jewish tradition—and the meal often included other family members who would have been offended at using a nonkosher wine to toast Moses’s passage from the land of Egypt.

Then, one year my father made a great discovery: kosher French wine! As a child I do not recall the vineyard, but I can remember the gusto with which he announced his discovery at the Seder. Indeed, we all cheered, as the sweet Manischewitz or Mogen David had become a standing joke among the children accustomed to my father’s complaints. The Seders continued even after my parent’s divorce, as my mother and father remained on amicable terms, and I noticed that the range of kosher wines available for Passover kept expanding.

Our switch from sweet to dry kosher wines paralleled the experience of many Jewish households. Millions of nonobservant American Jews viewed Passover as the one meal each year where items had to be kosher, and it thus provided a ready (if seasonal) market for dry wines produced in accordance with Judaism’s religious requirements. Increasingly affluent observant Jews, while a far smaller group, offered a more stable market, consistent with their interest in taking advantage of the increasing range of kosher products and kosher restaurants to more readily participate in American food culture.

The progression of kosher wine from sweet to dry seems a straightforward success story, similar to the expansion of other kosher food options. What was lost, however, is less appreciated. By the late 1940s Manischewitz was the first crossover kosher product, attracting not only substantial consumption from non-Jews but also considerable cultural visibility through widespread print, radio, and television advertising. The dry kosher wines that took their place on Jewish tables have not, by and large, made their way into Christian households, and their branding as kosher is indeed a detriment in the wine marketplace, quite unlike the benefits such association served for Manischewitz. Dry kosher wine may have been “better” by the standards of discerning consumers such as my father, but it was far more marginal to American culture than sweet kosher wine in its heyday—and sold far less. Kosher wine’s progression thus is also a story of contraction to a Jewish core market, a movement strikingly at odds with the contemporaneous advance of kosher processed food.

BOREI P’RI HAGAFEN—THE FRUIT OF THE VINE

The sweet taste of traditional kosher wine had nothing to do with European Jewish traditions. Instead its character stemmed from the materials at hand for kosher winemakers—the inexpensive Concord grapes grown in New York State close to East Coast Jewish communities. Derived from the hardy domestic Vitis labrusca genus, the Concord dominated the grape market in northeastern United States. It was a reliable product, resistant to the phylloxera plague that devastated European varietals in the late nineteenth century and tough enough to endure all sorts of growing conditions, such as the chilly weather of upstate New York. Originally shipped to cities in small lots intended for direct purchase by consumers and retail stores, growers shifted to bulk railcar lots around the turn of the century as the “inexpensive wine” market burgeoned. The producers of such “inexpensive wine” were immigrants flooding into Eastern cities (especially Jews and Italians), both small entrepreneurs making commercial brands and families crafting wine at home.

The Concord’s popularity did not mean it was a good wine grape. Highly acidic, making even “sour wine” from Concord grapes required adding large amounts of sugar so that it would ferment adequately; then more would be added to the mixture to create a palatable product that masked its “foxy” taste.1

The large Jewish demand for Concord wine was not, however, primarily to drink it with meals. Instead, wine fulfilled important ceremonial religious functions in the home. Wine was part of the weekly recognition of the Sabbath and integral to the Purim and Passover ceremonies. Wine helped to mark major life passages, from the bris (circumcision) of a male infant to the blessings recited in marriage ceremony, and was served to mourners at the first meal following burial. To immigrants coming from Eastern Europe, where grapes could not grow and most wine had to be made from raisins, the plentiful supply of purple Concord grapes (and the cheap sugar that could make it into wine) was yet another example of the plentitude of their new home.

Accorded its own particular blessing, blessed are thou, oh Lord our God, King of the universe, who created the fruit of the vine, wine preparation had its own complex set of rules designed to ensure it was for Jews—alone. It was not enough that all the ingredients used to make wine, such as clarifying agents, were kosher. Jewish ceremonial uses could be traced to ancient times, the same era when their Greek and later Roman rulers also used wine in ceremonies to their pagan gods—and imbibed quite a bit themselves. To firmly separate the Jews from their polytheistic neighbors, rabbis imposed stringent requirements to ensure that the wine drunk by the Jews was not yayin nesech (wine employed in pagan rites) or stam yeinom (wine made by non-Jews). Aside from ensuring that pagan ritual wine never touched Jewish lips, this prohibition also was inspired by chatanut, concern that social interaction over wine with non-Jews could lead Jews away from the Torah and perhaps even result in intermarriage.

To build a fence against such transgressions, rabbis mandated that only Sabbath-observant Jews could participate in making kosher wine from the time the juice began to flow from the grape to when the container holding the fermented liquid was sealed. After the barrel or bottle was opened, the smallest touch and movement of the container by a non-Jew would render the wine nonkosher. As promulgated in the ancient Middle East, Jews could neither consume nor benefit from yayin nesech or stam yeinom. With the decline of pagan religions, rabbis under Christian and Muslim rule moderated these rules to permit Jews to benefit from stam yeinom, that is, to become growers and dealers of nonkosher wine. 2

Averting the pitfalls of non-Jews handling open kosher wine required making yayin mevushal—cooked wine. Maimonides explained that “if the wine of a Jew is first boiled and then touched by a heathen, it may be consumed, even from the same cup used by the heathen, because boiled wine is not suitable for a libation for an idol.” Presumably since boiled wine was meant for cooking, not sociability, young Jewish men and women also would not drink yayin mevushal with those from other religions. For the early twentieth-century immigrants who either made their own wine or bought wine from Jewish wine dealers, the question of what constituted “cooked” wine was not a pressing issue. In most cases kosher wine of this era was not mevushal, made as it was by Jews and for Jewish consumption at home or in religious ceremonies. But, in time, how to define yayin mevushal would become a major halachic concern.3

Prohibition was a watershed for kosher wine. Article 7 of the National Prohibition Act permitted home and commercial manufacture of wine for sacramental purposes, but under strict limits. Households could make no more than ten gallons annually, and complicated procedures governed distribution by rabbis to their congregants. Consider what Atlanta’s Rabbi Tobias Geffen had to do to obtain wine for Passover. With an estimate in hand of what the Jewish community needed, he would contact a company licensed to make sacramental wine to see if it could supply that amount. Once he received confirmation through return mail, the next step was to bring the receipt to the local federal alcoholic beverage bureau for endorsement and permission to ship. After receiving legal approval, Geffen would write again to the manufacturer to confirm the order. Upon receipt of the wine, he then sold it to congregants from his home so he had the money to remit payment. If Rabbi Geffen ordered too much, he would have to dig into his pocket to pay the bill; if too little came in, the whole process had to be repeated so that sufficient wine would be available for ritual use. Not surprisingly, this cumbersome system encouraged widespread home manufacturing of kosher wine.4

Prohibition also made kosher wine a convenient way to avoid alcohol restrictions, especially by organized crime. Jenna Weissman Joselit has documented that demand for “kosher” wine skyrocketed in the early years of Prohibition, with shipments to New York City tripling between 1922 and 1925 to almost 1.8 million gallons. The evident fraud behind such demand resulted in a tightening of federal control over rabbis’ abilities to obtain wine for sacramental purposes, with shipments plummeting to just under four hundred thousand gallons in 1932, prohibition’s final year. This successful effort to suppress illicit “sacramental” wine use also meant, in all likelihood, that commercial kosher wine supplies were inadequate for New York City’s Jews. Shipments in 1932 were just enough for each Jew in New York to have the required four glasses of wine during Passover, and nothing more, hardly sufficient given wine’s other ritual purposes. Home production must have filled the gap—and, when Prohibition finally ended, entrepreneurs seized the opportunity to satisfy pent-up demand with new brands for Jewish use.5

“WINE LIKE MOTHER USED TO MAKE”

The Monarch Wine Company was the strongest entrant among the new kosher wine firms. Its founders were two friends who were in the paint business in the 1920s, Leo Star and George Robinson; they recruited George’s younger brother, Meyer, to be the new company’s attorney. When George died in 1935, Meyer took his place as the firm’s co-owner. Star kept a home in Fredonia, New York, in the heart of the upstate grape region, giving him the connections to make sacramental wine in the later years of Prohibition. Eager to expand sales when liquor once again became legal in 1933, the astute owners realized, as Robinson’s daughter Gale recalled, that “they needed a name that was well known in the Jewish world.” In an astute marketing decision, they sought out the Manischewitz food company, whose products were widely used among Jews, and negotiated an agreement to license the name for their wine. Monarch also relied on Manischewitz’s rabbis for kosher certification, ensuring that it benefited from the high regard among Jews for Manischewitz products, even though its namesake had nothing to do with actually making the wine.6

Befitting its association with Manischewitz, the wine bottle’s label was steeped in religious traditionalism. A light blue Jewish star dominated the brown label; inside the star a rabbi with a white beard, holding a prayer book in one hand and a glass of wine in the other, verified the wine’s branding as “New York State SACRAMENTAL Concord Grape Wine.” In the Hebrew text, Rabbis Itzchak Halevy Segal and Menachem Mendel Hochstein affirmed that this “wine from the fruit of the vine” was made under their supervision and “is kosher for Pesach for all of Israel.” Immediately below, if there was still any doubt about the wine’s kosher bona fides, the slogan emblazoned along the bottom declared, “WINE LIKE MOTHER USED TO MAKE,” connecting Monarch’s Manischewitz to the women during Prohibition who had made sure there was kosher wine available for their family’s use.7

FIGURE 6.1 Manischewitz wine bottle label, 1940s. From the Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York.

It was not until the end of World War II that Monarch’s Manischewitz emerged as the leading U.S. kosher wine. Before then the company’s products were not among those advertised by liquor stores and shopping emporiums for Passover use. Macy’s pushed its house Red Star brand of Concord grape wines, while liquor stores favored kosher wines by Marmok, Wirklich, Blue Diamond, and the Carmel brand produced by Jewish colonies in British Palestine. Hearns, which called itself “America’s Largest Liquor Store,” finally added Manischewitz “fine Passover wine” to its advertised specials in 1944, trumpeting its “special reserve quality” while warning it was only available in limited quantities. Gimbel’s and Macy’s added Manischewitz soon thereafter; in 1946 Manischewitz was the only brand promoted by Macy’s aside from its much cheaper Red Star varieties.8

Monarch’s wine made rapid progress in the late 1940s. The effectiveness of the Manischewitz brand name as an advertising device led two other kosher food producers, Rokeach and Streit, to offer their own varieties of kosher wine. Small brands also found space on the shelves of Jewish liquor stores, such as Shapiro’s California Wine Company, Hersh’s Hungarian Grape Products, and the Monterey Wine Company, but none had Manischewitz’s promotional resources or visibility. Regular New York Times advertisements during Passover stressed that Manischewitz was “the traditional wine for Passover.” Reaffirming the messages conveyed on its bottle label, advertisements asked readers to remember “Seder night at mother’s house, the way it used to be … and on the table, wine like mother used to make … Manischewitz Kosher wine.” Radio and even television advertising conveyed to a wide audience Monarch’s claim that Manischewitz was “America’s Largest Selling Kosher Wine.”9

Certainly, my family participated in the postwar demand for Manischewitz on Passover night. But its use did not extend far outside the Seder itself. For us, serious drinking on Passover meant imbibing slivovitz, a powerful 100-proof plum brandy that was made throughout Eastern and Central Europe, including Romania where my mother’s ancestors hailed from. As far back as I can remember, we would drink several shot glasses of slivovitz before sitting down for the Seder service and dinner. Evidently many other midcentury New Yorkers had a similar informal Passover ritual, as there were far more varieties of slivovitz advertised for Passover use in the 1930s and 1940s than brands of kosher wine. For all of Monarch’s success becoming the “traditional kosher wine,” its sales to Jews remained connected to specific rituals and holidays.

Reflecting the pattern of Jewish demand, Manischewitz sales spiked in September with the High Holy Days of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur and then again in the early spring with Passover and Purim. It had to accept returns from stores after April, as there was little demand until the end of summer. But during the 1940s the company noticed a curious phenomenon—returns actually were decreasing among retailers who held on to the wine after Jewish holidays. Clearly other customers wanted it. Then, stories began to circulate about New York’s African Americans requesting bottles of a kosher wine they called “Mani” that had a man with a beard on the label. By the early 1950s the pattern had become clear—there was substantial demand in the black community for Manischewitz wine such that Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter sales far exceeded Passover. Manischewitz had become the first crossover branded kosher product, several decades before Levy’s rye bread or Hebrew National hot dogs.10

African American affinity for kosher wine was national in scope. With a population five times the size of the Jewish community, their purchases stimulated a remarkable increase in kosher wine production. Manischewitz sold especially well in Washington, DC, Detroit, Los Angeles, and the South, while Mogen David, a similar wine made by the Wine Corporation of America, dominated Chicago and other Midwestern cities with large African American populations. Sales even grew internationally, as Monarch found customers throughout the Caribbean and northern Latin America, as well as a few locations in Asia. Kosher Concord grape wine, a product whose “annual output was once so negligible that it wasn’t isolated very carefully from the over-all statistics,” comprised 10 percent of all wine produced in America in 1953 with a total production of ten million gallons.11

The African American market for Manischewitz puzzled Morris Freedman, author of a long 1954 article in Commentary about the Monarch Wine Company. His curiosity was further piqued by the presence of reporters from African American newspapers at the inaugural tour of Monarch’s upgraded Brooklyn facilities, where the company unveiled sufficient capacity to make five million gallons annually. His own theory was that African Americans had learned of the wine through domestic servants receiving bottles of Manischewitz for the holidays from their Jewish employers. He didn’t follow up on the hint offered by one unidentified black reporter. Manischewitz is “like the wine their mothers and grandmothers used to make down South,” the unnamed reporter explained in an aside to Freedman. “Scuppernong grapes are much like Concord. You’ve got to add sugar.” It was an astute insight.12

The scuppernong grapes referred to by the reporter were the Concords of the South—or, if primacy as a wine grape is considered, Concord grapes were the scuppernongs of the North. Just as Concords grew well in chilly upstate New York, scuppernongs were unperturbed by sweltering southern weather and resistant to the fungus that devastated European grapes. Derived from native Vitis rotifundia, or muscadine grapes (much as Concord grapes were descendants of the domestic Vitis labrusca variety), scuppernongs provided wine for Southerners generations before New Englanders learned how to turn Concords into a beverage. While scuppernongs were carefully cultivated to drape over arbors, muscadine grapes were its wild cousin, growing prolific over trees, along hedgerows and fences, wherever there was enough water and sun. Scuppernong arbors were so commonplace that they provide a location for children’s play in Harper Lee’s classic To Kill a Mockingbird (1960). While used for other products, such as jams and fruit cakes, their availability meant that muscadine and scuppernong wines were widespread throughout the South.

Scuppernong grapes shared with Concords a high acidity and a musky flavor; hence the reporter’s observation that, to make wine from either grape, “you’ve got to add sugar.” Adding abundant sugar permitted completion of fermentation and made the product palatable. And the home recipes used to make wines from Vitis rotifundia grapes were remarkably similar to those for Vitis labrusca, even though widely separated in time and place. A mid-nineteenth-century North Carolina recipe directed that for “every gallon of juice take three pounds of white sugar” to make muscadine wine. Several generations later, the 1913 Dishes and Beverages of the Old South similarly recommended using three pounds of crystallized sugar for each gallon of liquid from crushed “dead-ripe” muscadine grapes to make a wine that was “a peculiar but indescribably delicious flavor.”13

Mid-twentieth-century kosher wine recipes were remarkably similar, even as they relied on Concord grapes. Located in the Passover section of cookbooks, these wines clearly were a complement to the special foods for that holiday and replicated well-worn home recipes. Leah Leonard recommended almost the same proportion of sugar—a little over two and a half cups per gallon—and advised that it would take three months for the wine to mature, enough time to make it in the late fall and have it ready for Passover. Little wonder these domestic wines, albeit made from different grapes, tasted similar.14

African Americans used wild and home-grown grapes to make wine even after national Prohibition ended, as many areas of the South retained a ban on alcohol sales. Robert Taylor, who grew up on a farm in Utica, Mississippi, in the 1950s and would enter the wine business himself, recalled that as a youth he helped to “climb the trees” to collect muscadine grapes, which his grandmother would turn into wine. The well-off white Southerners who enjoyed scuppernong wine at home also relied on the knowledge of their African American kitchen staff. “Two black women named Josie and Lena” presided over the kitchen of Mary Elizabeth Sproull Lanier’s grandmother and doubtless were the ones who prepared her scuppernong wine, made with the conventional three pounds of sugar for every gallon of juice. Either way, knowledge and experience of home winemaking was widespread among rural African Americans, including the hundreds of thousands who traveled to New York and other cities to seek better employment opportunities.15

As the African American migrants to northern cities moved into neighborhoods that had Jewish residents—and Jewish-owned liquor stores—it was easy for them to discover the sweet wine known as Mani. Whether introduced to it through holiday gifts (as Morris Freedman surmised) or through other means, sweet Manischewitz wine tasted familiar—and was easy to obtain. Its prominent religious overtones, and label copy describing it as a sacramental wine, eased acceptance by the often devout African Americans. Similarly, the appeal to Jewish traditions through the marketing slogan “Wine like mother used to make” unintentionally carried a welcome message for African Americans with southern roots, familiar with home-made scuppernong wine, and now wanting to enjoy a northern lifestyle that included access to brand-name consumer products.

“MAN-O-MANISCHEWITZ”

Manischewitz avidly pursued black consumers in the 1950s with a multimillion dollar advertising campaign created by the Emil Mogul agency. Print advertising emphasized Manischewitz’s popularity among leading culture figures and the qualities imbued by its kosher status. The Ink Spots, a prominent African American vocal group of that era, endorsed Manischewitz in a 1950 Pittsburgh-Courier advertisement. “Manischewitz kosher wine … harmonizes with us—sweetly!” they declared. “It’s our favorite wine, too.” A 1954 advertisement in Ebony used endorsement by bebop artist Bill Eckstein to declare that those drinking Manischewitz “drink with the stars of the entertainment world to whom nothing but the finest is good enough.” The “quality and taste” enjoyed by these performers reflected how Manischewitz was “the traditional kosher wine” that could trace its history “back to Biblical days.” And to make sure there was no doubt of the connection with the wine’s kosher character, a prominent picture of the Manischewitz bottle graced both advertisements, with the serious rabbi on its label dominating the foreground.16

The company also poured money into radio spots intended to embed proper pronunciation of the Manischewitz name in the minds of black consumers—and, in so doing, add to brand recognition. Using the syncopated tag line, “Man-O-Manischewitz, What a Wine,” the Emil Mogul agency “gave very careful pronouncing instructions to the announcer,” including a phonetic spelling of the wine’s brand name, “Man-i-shev-itz” so that consumers knew how to ask for it. These promotions were placed in programs that played “race” music and were conducted by “popular local personalities” in the black community, such as Jack Surrell, the legendary DJ for Detroit’s WXYZ radio station. And these promotions always linked the wine’s quality with its kosher status; listeners were reminded that “Manischewitz is kosher wine. … That means it’s so pure, it’s also used for sacramental purposes.”17

Manischewitz advertising oriented toward Jewish consumers maintained the “Man-O-Manischewitz” tag line, but in other respects followed completely different themes. Maintenance of tradition, and of the established ways of celebrating Jewish culture, dominated its messages. “If it weren’t Manischewitz, Grandma wouldn’t serve it for Passover,” declared a 1956 advertisement in the New York Times. By including promotion for Manischewitz matzoh, gefilte fish, and macaroons and declaring “Passover-Time is Manischewitz-Time,” the advertisement also linked Monarch’s Manischewitz wine with venerable kosher products made by an entirely different company—a distinction invisible to readers.18

In the late 1950s a new advertising agency, the Lawrence Gumbiner firm, briefly tried to reposition Manischewitz as “everybody’s wine … because it tastes so good.” These efforts sought to expand sales among white consumers by deemphasizing its Jewish association and kosher status. Gumbiner shifted expenditures away from radio shows that reached African Americans and toward mainstream television. Similarly, it suspended the Ebony advertising campaign in favor of using almost its entire magazine budget for full-page glossy Life magazine advertisements featuring men and women who did not look particularly Jewish. It even halted the Passover-series New York Times advertisements that had been a centerpiece of Monarch’s promotional strategies towards Jews. These deliberate efforts to increase sales by “shatter[ing] the image of Manischewitz as a Jewish ceremonial wine” failed to make sustained headway among non-Jewish white consumers. Monarch fired the Gumbiner firm in 1960.19

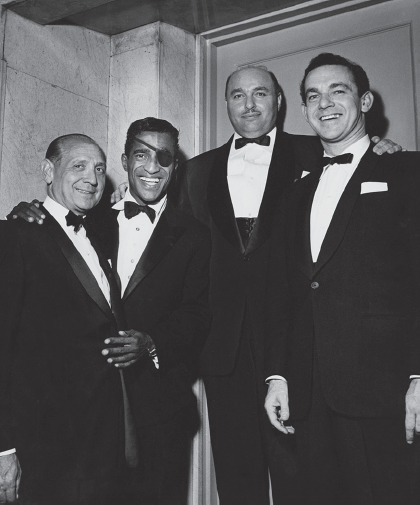

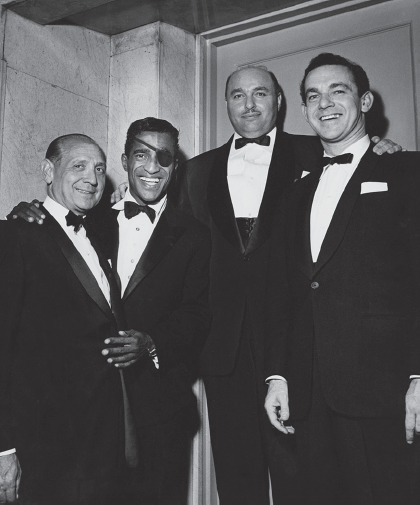

With a solid and yet limited niche market among Jews, and little evidence of interest from other white groups, the company reverted to the strategy of expanding African American demand for its products. Monarch recruited its former account executive at the Emil Mogul Advertising Agency, Nort Wyner, to become the company’s director of sales and advertising. Meyer Robinson “adored this guy,” his daughter recalled, as the creative Wyner was schooled in the new world of postwar advertising methods. Under his direction, magazine advertising shifted back to focusing on the African American market, with Ebony absorbing 85 percent of the entire magazine budget by 1973. And, in a brilliant stroke, Wyner recruited Sammy Davis Jr. (made famous as a member of the rat pack through his movies with Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin) as Manischewitz’s television front man. Nattily dressed and filmed while knocking out a seemingly impromptu tune on the piano, Davis encouraged African American men to be a bon vivant like himself by drinking Manischewitz on the rocks. A convert to Judaism who was hardly a “Richard Pryor,” as one former company executive reflected, Sammy Davis was not likely to scare off consumers who drank Manischewitz for traditional purposes.20

To increase sales, Monarch even expanded its product line directed toward African Americans. Sustained efforts went into the launch of Cream White Concord in 1968, a year whose events might have discouraged other white firms from seeking to grow sales among black consumers. While featuring the Manischewitz name, the bottle’s shape emulated a VSOP brandy, rather than the traditional design, and bore a simple and elegant label with gold lettering—and a much less visible rabbi. This appeal to upscale style reflected a common judgment among advertisers that African Americans preferred to buy the best kind of alcohol, rather than cheap brands. Seeking to build on its positive brand image, its Ebony advertisements introduced Cream White Concord by asking, “How do you tell wine lovers about a different Manischewitz wine”? While its kosher status was less evident (though still confirmed on the front label), the wine’s connection to Manischewitz and its traditional Jewish wines was a centerpiece of the company’s marketing efforts.21

FIGURE 6.2 From left to right: unidentified, Sammy Davis, Jr., Meyer Robinson, and Jack Carter. Collection of Gale Robinson.

The contrast with efforts to sell white consumers on the new wine could not have been greater. Rather than building on Manischewitz’s reputation to promote Cream White Concord, the company sought to minimize its association with the new product. New York Times advertisements featured a hand hiding the bottle’s label, reinforced by text that advised, “Don’t let them see the label until after they taste the wine.” Consumers seeking to introduce it to their friends were counseled to dispense sips before revealing the brand so that its connection with Manischewitz would not detract from appreciation for its taste. “This is terrific,” the advertisement quoted an anonymous consumer saying. “Y’know, if I’d seen the name, I might never have believed it,” he then admits. Such pessimism conceded the circumscribed appeal of Manischewitz wine to Jews—and to all white Americans.22

Cream White Concord quickly became the company’s sales leader, largely due to African American demand—and an advertising budget that reached $4 million by the late 1970s. “The African American community was dedicated to the Manischewitz name,” reflected former company executive Marshall Goldberg, “and when they saw a new product that was packaged so beautifully, it gave them a whole new product to drink.” In 1981 Forbes magazine could declare that the typical Manischewitz drinker was an urban blue-collar African American man rather than an ethnic Jew.23

As a brand built through savvy marketing, Manischewitz wine had an outsized presence in American popular culture. In addition to displaying billboards, placing magazine, radio, and television advertisements, and developing extensive in-store displays, company president Meyer Robinson was an inveterate promoter. “When he would go someplace and introduce himself,” his daughter Gale Robinson recalled, he always would put out his hand and say, “Meyer Robinson, Manischewitz wine.” (She kidded her father that someday his approach would generate the comeback, “how do you do, Mr. Wine.”) With his wife Roslyn, Robinson frequently drove into Manhattan from their Long Island home to “go to the Copacabana and the Latin Club and that kind of thing because of the people involved”—especially disk jockeys. Robinson personally got to know prominent radio personalities such as William B. Williams, who favored playing singers such as Lena Horne and Frank Sinatra on his WNEW shows, and Barry Gray, an early pioneer of talk radio on WOR. Knowing their influence, Robinson cultivated these relationships, with the objective that they would “in some way mention Manischewitz” on the air. While the wine’s clientele may have been predominantly African American and Hispanic, its prominence was that of a kosher wine, a Jewish wine, lending a visibility to kosher products that permeated the wider American culture. When astronaut Buzz Aldrin invoked the by then iconic phrase “Man-O-Manischewitz” to capture the awe he felt stepping on the moon in 1973, he also inadvertently certified the remarkable success of a quarter-century of company marketing efforts.24

FIGURE 6.3 Buddy Hackett, Jackie Robinson, and Meyer Robinson. Collection of Gale Robinson.

Among Jews, though, Manischewitz was not doing so well. While my father may have turned up his cultured nose at sweet kosher wine, my mother increasingly viewed it as fit for “winos” rather than upwardly mobile Jews. She would tell us that alcoholics drank sweet kosher wine because it was a way of getting drunk quickly and imbibing enough calories to avoid having to spend money on food. Her prejudice was fanned by the movement of poor Puerto Ricans and African Americans into our Upper West Side neighborhood and the visible cultural changes this entailed. Business names on store fronts switched from English to Spanish, and streets that had been sedate and quiet when she walked them as a child now were lined, in the summer, with people sitting on stoops, some drinking from bottles in paper bags. Her fear was such that we were forbidden to walk between Broadway and Central Park West, except along the wide east-west crossings at 86th, 79th, and 72nd streets. In her anger at these changes, my mother did not distinguish between Manischewitz and those kosher brands that aggressively catered to the “wino” market, such as Mogen David, which produced MD “Mad Dog” 20/20—twenty-ounce bottles containing wine that was 20 percent alcohol—to compete with Thunderbird, Ripple, and other fortified high-alcohol wines. Sweet kosher wine, regardless of brand, had become a beverage tolerated only for tradition’s sake on Passover and was not to be seen in the house at other times.

Among the Orthodox, Manischewitz suffered a more fundamental challenge—doubts that it was kosher at all. For decades, the Monarch Wine Company had relied for certification on the same rabbis employed by the Manischewitz food company. The OK certification agency included Manischewitz in its Kosher Food Guide, but the Orthodox Union steadfastly refused to endorse it. “The rabbis always were the issue,” recalled Marshall Goldberg. “The Orthodox would not recognize our rabbi and the K with a circle around it on the label.” As OU’s certification program expanded, and the observant community became more demanding, Monarch’s Manischewitz suffered under a whispering campaign that it did not meet kosher norms.

Monarch faced relentless criticism from the Orthodox, as Gale Robinson recalled, for “having non-Jews working in the winery.” As job opportunities for Jews improved following World War II and new migrants moved to Brooklyn, the composition of the plant’s workforce changed accordingly. By the 1960s there were in fact “many, many non-Jews working at the plant,” Marshall Goldberg admitted, with most of the remaining Jews working “upstairs” in the chemical and scientific research areas and as salespersons, and not in the production jobs that actually made the wine. Among the Orthodox, these changes violated one of the first rules for making wine kosher—that only Sabbath-observant Jews could play a role in production from the time the grapes were crushed to when the bottle was sealed.25

Conservative Judaism, the variant that my family adhered to, was firmly behind Manischewitz. At the behest of its governing Rabbinical Assembly, Rabbi Israel Silverman delved into Jewish law to determine if the ancient requirements governing kosher wine were still applicable in the modern era. His 1964 responsum, “Are All Wines Kosher?” argued that modern production methods rendered the ancient rabbinic prohibitions obsolete. Rabbi Silverman held that mechanized operations in large factories meant that gentile production workers could not touch the wine “from the moment the grapes are placed in the crusher machine until the entire production process is complete and the wine resulting from it placed in sealed containers” even if they managed those operations. While such wine might still be stam yeinom, wine made by non-Jews, the absence of any physical contact with gentiles meant it could be permitted for Jewish consumption. Drawing on a long lineage of lenient opinions, especially those of Moses Isserles, Silverman nonetheless emphasized how dropping the rabbinic restriction on stam yeinom did not extend to permitting its use on Passover—as unacceptable leavening agents might be in the wine—and for other religious functions so as to “enhance the ritual of the mitzvah.” Manischewitz thus was not only acceptable, but, along with other Jewish-made wines, preferred for traditional uses. Conservative Jews drew on Silverman’s responsum to argue, as Rabbi Meyer Hager did a few years later, that Manischewitz was “kosher in every respect.”26

The breach between Conservative and Orthodox over non-Jewish workers in wineries was compounded by profound differences over mevushal requirements. All Manischewitz wines were mevushal to the satisfaction of its supervising rabbis—a status they translated as “boiled” rather than cooked. The machinery at the company’s disposal, however, did not heat wine to anything close to 212 degrees. Monarch relied on commercial technology initially developed to pasteurize milk to “boil” its wine; to comply with U.S. Public Health service rules, this equipment heated liquids in large vats to 145 F for thirty minutes. Since Monarch already relied on vats connected by hoses and pipes to mix wine with sugar, adjust color, and filter impurities, it was relatively straightforward to incorporate the milk pasteurization technology into its manufacturing operations. “The wine is bottled at 140 degrees,” company scientist Monroe Coven told visitors, immediately following pasteurization. Once mevushal, opened Manischewitz wine could be passed by a person of any religious persuasion at an event without compromising its kosher status. Rabbi Silverman, along with other Conservative rabbis, was satisfied that Manischewitz’s mevushal methods were in accordance with Jewish religious requirements.27

The Orthodox did not agree. Barely a year after Silverman’s essay, Rabbi Moshe Feinstein issued what was in essence a sharp riposte, though without mentioning him by name. His responsum’s timing and content, though, indicates that it was a rejoinder to Silverman’s leniency. In it Feinstein concentrated on the issue whether conventional pasteurization was sufficient to render a wine mevushal. His challenge was to translate the traditional sensory criteria of “cooked” into a modern numerical standard. After evaluating several areas of rabbinic debate, Feinstein concluded that a reduction in wine’s volume was the proof needed to determine if it had been heated enough to be “cooked” in compliance with rabbinic requirements. Citing a chemist for support, Feinstein determined that 165 degrees F was the minimum temperature required—that is, twenty degrees warmer than the pasteurization achieved by Manischewitz using vat technology. While Rabbi Feinstein did not comment on Manischewitz explicitly, the implications of his ruling were clear; given his views, the Orthodox Union would not extend certification to Manischewitz.28

Compounding his differences with Silverman over mevushal requirements, Feinstein also did not agree that the automatic processes used by Monarch changed the traditional requirement for observant Jews to be involved in winemaking at all stages of the process. While Monarch continued to find individual Orthodox rabbis to certify its wine, without the OU seal of approval doubts remained about its kashrus.29

Monarch wine made no efforts to satisfy its Orthodox critics, even as its sales stagnated in the late 1970s. Since “the die had been cast as far as whether Manischewitz was acceptable,” reflected Goldberg, “it wasn’t really worth it” to go through the expense of obtaining OU certification. With Jews comprising at most 15 percent of Manischewitz’s customers, an advertising campaign saying, “look, we have changed,” designed to attract Orthodox consumers, didn’t make sense. “We’re certainly not going to let the tail wag the dog” was the unfortunate description of the wine’s Jewish consumers offered by Manischewitz’s advertising agency in 1981—a telling if undiplomatic admission about its consumer base.

Instead, the company looked outside the Jewish market. It acquired highly profitable distribution rights to the Chinese Tsingtao beer and invested heavily in flavored domestic wines oriented to its African American and Latino customers. In 1981 three-quarters of the company’s $4 million advertising budget went to promote Piña Coconnetta, a piña colada–flavored wine beverage, which Forbes wryly noted was “not exactly what you would call a sacramental drink.”30

With its focus remaining on sweet wines, Monarch’s owners denied in vain that there was a shift underway among assimilated Jews such as my father, along with other Americans, toward dry varieties. It may be “chic to be dry,” company sales director Cliff Adelman lectured Forbes in 1981, but in his opinion the “upward mobility-group” that preferred dry wines “represent zilch population-wise.” He would be proven wrong. The interest in French wines and California varieties made from European grapes accelerated in the 1980s, such that by 1985 80 percent of the wine consumed in America was table wine. Black consumers began to switch to dry wines as well, sending sales of Cream White Concord into a tailspin and frustrating the company’s investments in Piña Coconnetta and similar products. The reversal was so sharp that, just three years after he ridiculed Forbes for suggesting “that people drink dry,” Marshall Goldberg admitted to the New York Post that the company’s association with sweet wine “blocks some consumers from buying.” Shortly thereafter, the partners gave up and sold the Manischewitz brand to the Canandaigua Wine Company at a considerable profit, where it became just one of its stable of Concord wine brands, thereby ending this remarkable saga in American Jewish wine culture.31

“KOSHER DOESN’T HAVE TO MEAN SWEET”

The French kosher wine we started serving for Passover came, in all likelihood, from the Royal Wine Company, better known as Kedem. Initially established as the Herzog Wine and Spirits Company in Czechoslovakia in the early 1800s, the firm was one of many European wine companies created by Jews to serve both their own communities and to reach a gentile market. Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph even took note of the company, making it a supplier of wine to the crown and anointing company president Philip Herzog a baron. In the 1930s, however, the rise of Nazism forced the Herzog family into hiding, with several dying in the Holocaust. Philip’s grandson Eugene survived the war years, only to find his company in the crosshairs of the pro-Communist Czech government and its program to nationalize private firms. In 1948 Eugene fled Europe, his family’s fortune gone, and sought to create a new life in America.

Eugene joined other Jewish refugees on New York City’s Lower East Side where he looked for opportunities to use his particular expertise. While Manischewitz dominated the market, enough customers were interested in variety to support a half-dozen small companies making sweet Concord grape wines. With his knowledge of the wine business, Eugene joined the Royal Wine Company as one of eight partners in 1948; it received certification from the Kosher Food Guide in 1954.32

The founders of Kedem and Manischewitz could not have been more different. Meyer Robinson was a quintessential product of mid-century Jewish culture, descended from immigrant parents and proudly Jewish as well as deeply embedded in American culture. He was an avid Brooklyn Dodgers fan, often bringing the team to the winery for meals, and a friend to Jackie Robinson when he broke baseball’s color line. While kosher at home, and a firm believer that the Friday Sabbath dinner was sacrosanct, he was comfortable in nonkosher settings and enjoyed lobster and other dishes that were, without doubt, treif.

FIGURE 6.4 Brooklyn Dodgers at Monarch Wine. Collection of Gale Robinson.

The Herzog family was instead part of a post–World War II Jewish refugee generation that carried with them lived experiences and vivid memories of the efforts of the Nazis and Soviet Communists to eradicate Judaism. Deeply embedded in Jewish Orthodoxy, the five Herzog children attended yeshiva; one became a rabbi. While Monarch Wine’s owners looked to associations with American life to brand their wine—selecting the well-known Manischewitz name to aid marketing efforts—Eugene Herzog’s choice was embedded in Jewish tradition and his family’s European odyssey. He drew from the emotional Hashiveinu prayer familiar to synagogue-attending Jews, sung by the congregation when the traditional scrolls of the holy Torah were returned to the ceremonial ark where it was kept between services. Its closing stanza, Chadesh yameinu ke-kedem, translates as “renew our days as before,” with ke-kedem meaning, “as before.” “It was a wish,” reflected Eugene’s son David. “That’s what my father wanted,” for the family’s fortunes to return, “as before.” The name was both a brand and an expression of hope among a particular generation of Jews, the post–World War II refugees, that their life in America would permit a restoration of the pious Orthodox communities wiped out by the Holocaust.33

While the wine’s name may not have had meaning for consumers unfamiliar with Jewish synagogue rituals, it did telegraph to postwar Jewish immigrants that Kedem was a wine for them, one produced by observant Jews from their own community. Nonetheless, the Royal Wine Company struggled for several decades. Each partner produced and named their own wine; adding so many choices to an already crowded marketplace meant none did very well. The company survived largely due to its contract to distribute the Israeli Carmel wines, which naturally had distinctive appeal. Gradually Herzog bought out his associates, finally becoming sole owner in 1958 when the final partner left, amicably, taking with him the Carmel distribution business.

Herzog turned the Royal Wine Company into a family business, depending heavily on his sons’ labor. “He had his kids working their butt off,” recalled David. As a yeshiva student in his early teens, David Herzog would return home to help harvest grapes in the fall, then again to help the company through the busy Purim and Passover season. “Seven days after my wedding,” he reflected with a smile, “I was loading trucks.”34

Seeking new market niches for his grape products, Eugene Herzog developed Kedem grape juice in the late 1950s. It was a boon for the company, with sales boosted by Passover consumption and crossover demand in Puerto Rico and in other Latino markets. For its core kosher consumers, Herzog produced a new naturally sweetened Concord wine, using grape juice concentrate rather than sugar to improve its taste. Together, these products gave the Royal Wine Company something distinctive in the marketplace, generating both income and visibility for its Kedem brand.

Herzog also sought to make inroads among the Orthodox—already skittish about the kashrus of Manischewitz—by securing OU certification for Kedem wine and grape juice in 1970; by the mid-1970s, Kedem was the only wine producer with the OU’s imprimatur. At the same time that Manischewitz was aggressively seeking non-Jewish consumers, Kedem was busy consolidating its position as the Orthodox Union’s preferred kosher wine.35

Kedem also began to explore alternatives to sweet kosher wine entirely, especially as David Herzog assumed a larger role in the company’s operations. The youngest of Eugene’s sons, David had left the family business to work as a Wall Street analyst for almost six years. Upon returning to Kedem in the early 1970s, David brought a new attention to marketing to a company that had been principally focused on production. “Because of my Wall Street background,” he recalled, “I saw the world in different angles.” What he especially learned was that in order to reach new customers “you have to give them something unique.” Since Kedem was too small to “beat up” on bigger companies by competing directly, it had to look for market niches that were not yet occupied.

Dry kosher wine would become just that “something unique” for Kedem. In the late 1970s, David fortuitously encountered a Jewish winemaker from France who was touring Kedem’s upstate New York winery; he asked if Kedem would be interested in distributing his kosher Bordeaux wine in the United States. David’s brother Yankel demurred, as he felt the French wine would cut into their own sales; but David argued for experimenting with a dry wine the company had not actually made. “The world is changing,” he recalled telling his brother. “People start to drink more dry wines.” So he gambled by buying one shipping container amounting to 750 cases; at the time “a lot of money to us.”

For a leading Jewish company to sell dry French wine for use on Passover was news—at least among those who followed wine. The New York Times’s well-known wine critic, Frank Prial, took note of Kedem’s audacious move. The “Royal Kedem line of kosher wines,” he announced in his April 5, 1978 “Wine Talk” column, “now includes three imported Bordeaux” all of which, he quickly reassured startled readers, were “strictly kosher” and “bordeaux superieure in rating.” To those “elderly traditionalists” who wrote in to him promising to “wreak various types of mayhem” if forced to drink anything but traditional kosher wine, he admonished, “we are talking about dry wine. Dry is not the opposite of wet in the wine world; it is the opposite of sweet.”36

Prial’s widely read column was a sensation in the New York metropolitan area. By the end of the day Kedem had sold out its entire stock, much to the frustration of some liquor stores, which had been initially wary of this peculiar new thing, dry kosher wine. “That was the beginning of our imported wines,” Herzog recalled.

With this success, David Herzog sought to expand the company’s imported wines to include Italian vintages. Going through his father’s old files, he discovered one labeled “Italy” that contained an unsigned agreement to make a kosher Asti Spumante wine through the Bartenura winery. While the Italian company was interested, Eugene explained that Kedem had been unable to locate the Sabbath-observant Jews it needed to make the wine as required by kosher law; the deal had fallen through. With his father’s encouragement, David tried again. He located the winery, and then secured help from the Orthodox rabbis for Milan’s Jewish community to recruit workers to handle operations for a special production run of kosher wine. Kedem paid for this help, thereby funding significant improvements in the facilities available to Milan’s Jews.

With a growing stable of dry kosher wines, Kedem decided to go on the offensive. In 1982, just as Manischewitz’s troubles were growing, Kedem launched a remarkably successful marketing campaign around the slogan “Kosher needn’t be sweet—just special,” and declared, in case readers didn’t get the point, that “special means Kedem.” Large advertisements reinforced the company’s message by including pictures of its “special” wines: a French Bordeaux, Italian Bartenura Soave, Spanish Ararbanel Rioja, and Kedem’s own California Chenin Blanc. The advertisements, appearing in small Jewish periodicals such as the Jewish Chronicle of Pittsburgh and the Kashrus Newsletter as well as the New York Times, appealed to refinement rather than tradition, promising that Kedem’s wines were “specially selected for the finesse and character that lingers happily on your palate.” The slogan was so compelling that New York’s Garnet liquor store used a slightly modified version, “Passover wines (needn’t be sweet just special)” and listed its kosher inventory by nation of origin—just as it did nonkosher wines.37

The Royal Wine Company steadily expanded its stable of dry wines with a strategy of adding more imported varieties. Drawing on its successful Bartenura experience, Kedem sought out relationships with Orthodox synagogues abroad whose rabbis and members could be drawn on to produce kosher runs of local wines. “In most places we have local communities who have been trained to do the work,” Herzog explained to Montreal Gazette wine critic Bill Zacharkiw, doing so “under the supervision of the estates’ winemaker.” Some of these relationships developed into virtual international outposts of the Kedem Company that could be flexibly enlisted to make wine. Its crew of Argentine Jews also did service in Chile to create kosher wine there, and a pool of thirty-five reliable Sabbath-observant Jews based in Western Europe produced kosher wine on fifteen to twenty estates in France, Spain, and Portugal. It was a brilliant way of economically expanding Kedem’s inventory; using already active vineyards to make kosher wine allowed the company to benefit from the credibility of established brands. The appeal of Kedem’s wines among observant Jews is apparent; Passover sales that had once comprised 80 percent of the company’s business had fallen to 35 percent by 1990. The company was now selling a great deal of its wine throughout the year to Jews wishing to have it with dinner and on special occasions.38

While expanding its line of dry wines, Kedem also sought to increase sales of its traditional Concord grape vintages by eroding Manischewitz’s standing among observant Jews. Its advertisements prominently displayed the OU symbol, the endorsement denied to Monarch’s wines, a quiet but unmistakable affirmation of Kedem’s superior adherence to kosher standards. In public statements, Kedem spokespersons consistently reinforced Jewish doubts about Manischewitz by emphasizing its nonwhite customer base. “We target the Jewish market,” David Herzog told the New York Times in 1984. “Manischewitz targets the entire sweet wine market, which includes many blacks and Hispanics.” A couple of years later he made the same point to a Long Island paper widely read by observant Jews, asserting (with slight exaggeration) that “90 percent of their [Manischewitz’s] sales are not going to the kosher market.” As Kedem also sought sales among non-Jews, Herzog’s comments were disingenuous. But they did serve the objective of branding Manischewitz as a wine that was not really meant for observant Jews, despite its kosher lineage.39

Kedem continued to air similar themes even after Manischewitz’s new owner, the Canandaigua Wine Company, secured OU certification. A radio and point-of-sale campaign in 1991 purported that Jewish consumers had selected Kedem over Manischewitz in a head-to-head competition—sponsored, of course, by the Royal Wine Company. The radio advertisements featured two men with Yiddish accents expressing their preference for Kedem, while point-of-sale ads showed, as the Los Angeles Times reported, “a bottle of Kedem standing upright over a knocked down bottle of Manischewitz, and was headed, ‘The chosen one.’” The attack, not only on Manischewitz’s taste but on its legitimacy as a kosher wine, was reaffirmed by a Kedem spokesperson who, according to the newspaper, “sought to question Manischewitz’s Jewish credentials by noting that much of its success derives from the popularity of Manischewitz among non-Jews, especially blacks.” Outraged by the campaign, conducted during the 1991 Passover season and based on a dubious competition, Canandaigua secured a court order forcing Kedem to remove the advertisements from radio stations and liquor stores. By that time, however, the damage already was done.40

Despite its success among Jewish consumers, wine critics nonetheless viewed Kedem’s early dry wines as “mediocre,” in the blunt statement of Baltimore wine columnist Michael Dresser. Frank Prial, generally one of Kedem’s boosters, nonetheless advised wine consumers in 1991 to just “try the lower-priced” of the company’s Herzog Cabernets, as “it may fulfill all your needs.”41 Recognizing the need for greater winemaking expertise, the Herzogs hired Peter Sterns to head up the company’s wine operations. After a career with the large California companies of Robert Mondavi and J. Lohr, Sterns had made a name in kosher wine through his work with the acclaimed Israeli Golan Heights Winery in the 1980s. Familiar with both California grapes and kosher practices, he was able to steer Kedem toward far better vintages, and, in 2005, to open its own California winery in Oxnard, just north of Los Angeles.42

Kedem’s owners realized as well that improving mevushal technology was integral to creating better wines. The best wine grapes and vintages could be undone by the demands of heating wine to make it mevushal. In so doing, however, the large Royal Wine Company actually lagged behind newer innovative companies. The true breakthroughs in making high-quality kosher dry wine took place among small winemakers who figured out how to adapt technology developed for pasteurization of fruit juice to make kosher wine mevushal. And these winemakers came not from the Jewish traditions of the East Coast, but instead from California’s efflorescent new wine industry.

Ernest Weir’s Hagafen winery (still in operation) was the pacesetter among the new California-based kosher wine operations. Weir had twenty-four years of experience in California wineries such as Domain Chandon before he set out, in 1980, to create his own kosher vineyard. He later attributed his inspiration to memories of attending Passover Seders in his late teens, “our best holiday of the year,” and yet having to drink “this wine that we hate.” Schooled in the boutique wine making methods that had proliferated in California since the late 1960s, Weir was able to create high-quality kosher wine at Hagafen. After a decade of operations, the Wine Spectator accorded his kosher Cabernet Sauvignon a strong 91 rating (out of 100)—far better than Kedem’s California and European wines, which it termed merely “reliable.”43

Not far from Hagafen, another influential vineyard drew on European traditions to make some of its wine kosher. The St. Supery Winery was founded by Robert Skalli, heir to a wealthy French-Algerian family with deep roots in the wine trade. Seeking a foothold in California as part of the family’s global wine business, Skalli established St. Supery in California’s Pope Valley in 1981 and appointed Michaela Rodeno (who had worked with Ernie Weir at Domain Chandon) as its CEO. Drawing from European practices familiar to the Jewish Skalli family, St. Supery brought in rabbinic supervision so it could prepare a short run of a kosher for Passover wine called Mount Madrona.44

Hagafen and St. Supery quickly had to address the difficult challenge of making their wine mevushal. Weir originally resisted, concerned that doing so “might be harmful to the quality of the wine.” But the initial “acceptance—or lack of acceptance” of his new kosher wine made him realize that making it mevushal would allow it to be “served in a hotel or in a restaurant” and thus increase sales, as “it really wouldn’t matter who touched the wine.” Still concerned about the effect heating wine would have on its quality, Weir departed from past mevushal practices by adapting the flash pasteurization methods used in fruit juice manufacturing. Employing fundamentally different technology than Manischewitz’s large, heated vats made it possible for Hagafen to produce high-quality mevushal wine.

Vat pasteurization, by all accounts, was hard on wine, much as it might have worked adequately for milk. The contents of the large tanks (holding up to fifty thousand gallons) took time to heat to 145 F and then had to be held at that temperature for thirty minutes, a slow process with deleterious effects. In a typical complaint about vat-pasteurized wines, Chicago Sun-Times wine critic Dee Coutelle complained that most “had a boiled character, lacking weight and body.” These were damning phrases for consumers wanting good wine.45

Flash pasteurization, known as “high temperature short time” (HTST) pasteurization by the trade, had more potential to produce good mevushal wine. The technology first emerged in the U.S. fruit juice industry when scientists determined that sterilization at high temperatures required far less time than at lower temperatures; pasteurization that took thirty minutes at 145 F could be achieved in a few seconds at 185 F. The HTST systems relied on heat exchangers that used closed pipes containing the juice to pass adjacent to plates or coils heated by scalding hot water; the two liquids never touched. Heating destroyed enzymes and bacteria that could spoil the juice, and units also typically contained cooling sections that could reduce the temperature rapidly to avoid discoloration or loss of nutrients. With skyrocketing demand for apple and orange juice in the 1950s and 1960s, equipment firms developed sophisticated systems that allowed precise control over the temperature to which the liquid was heated and the length of time it remained in that state; the appeal for winemakers seeking a gentler mevushal process is evident.46

With California’s large agriculture industry, Weir had ample opportunity to experiment with flash pasteurization units. In 1985 he rented the HTST equipment of an apple juice manufacturer located an hour away to successfully produce his first mevushal wine. He recalled that the unit “could set the temperature to exactly where I wanted [180],” so it met Rabbi Moshe Feinstein’s standard, and then “chill it immediately” to 60 F. In an extraordinary contrast to the slow (and damaging) vat procedure, the HTST unit could bring a quart of wine to the mevushal temperature in under two seconds and then cool it down just as fast. Soon Weir discovered a more convenient unit—one at St. Supery, just twenty minutes by car. St. Supery had in turn bought it from the Weinstock winery, a short-lived kosher operation, which in all likelihood had obtained it from a juice producer. In the mid-1990s St. Supery’s “mevushalatar”—as workers referred to it—was used by Kedem as well as by Hagafen and St. Supery to create mevushal wines.47

Modifying HTST systems designed to make apple juice for the exacting production of wine was not as easy as it may sound. For HTST systems to heat (and cool) liquids so quickly, consistently, and thoroughly, filtering systems needed to first remove solids and impurities that could impair the machine’s effects. Additionally, pipes had to be designed in such a manner that complex fluid dynamics rotated the liquid to ensure equal exposure to the heating elements. Wine producers had to choose between parallel pipes or plates to heat and cool the liquid and decide the placement within the manufacturing process: just after pressing the grapes and before fermentation or as the last stage before bottling. Modifying HTST systems for mevushal purposes and to create high-quality wine quickly became a place for widespread tinkering with existing technology to better adapt it to wine production—and to create competitive advantage.

Kedem’s initial efforts to adapt HTST technology began in the late 1980s and continued steadily thereafter. “We did a study with UC-Davis,” David Herzog recalled, and “spent a lot of money with them on the mevushal process.” (Some sources indicate that these expenditures were in excess of $1 million.)48 While the Davis researchers helped the company, there were “certain things they didn’t pick up”; subsequent improvements were developed internally by “knowledgeable people” on its staff. Kedem experimented with “different systems of chilling, different systems of heating, different systems of filtrations,” Herzog explained, “so that everything just works right.” Knowledge and techniques accrued through these efforts were proprietary and not shared publicly. “There’s only three people, four people who know it,” Herzog explained about Kedem’s closely held mevushal technology, “and all the last name is Herzog.”

Ernie Weir similarly experimented with several HTST systems for his mevushal process. After using the old Weinstock equipment for a number of years, he bought an “off the shelf” unit the manufacturer had adapted for his specific requirements and “integrated into a new system of heating and cooling.” While successful, Weir remained watchful of opportunities to improve his technology. Similar to Herzog, Weir explained that he “was not at liberty to describe” the machinery, as doing so might give other firms a “competitive advantage.”

Driving the expensive process of creating mevushal wines was the desire to expand sales to hotels, restaurants, and caterers for large events. The likely presence of non-Jewish staff whose touch would render non-mevushal wine nonkosher compelled this choice. “We can’t sell a caterer or restaurant wine which is not mevushal,” Herzog explained. Simply opening up the bar mitzvah and wedding market was a boon, as maintaining the kashrus of these events when there was a non-Jewish wait staff required serving mevushal wine.

Systematically making kosher wine mevushal helped reach additional markets—but it also placed new burdens on its acceptance outside observant Jewish circles. Heating wine, albeit briefly, to 180 F profoundly affected its chemistry; if performed before fermentation (the usual practice for white wines), new enzymes had to be introduced to replace those destroyed in HTST systems. Heating wine after fermentation (the general practice for reds) killed the enzymes that aged it, significantly affecting maturation in the bottle. In the case of Manischewitz, the mevushal process was an asset, as it meant the wine kept longer without spoiling, even if not refrigerated. But halting wine’s aging process was abhorrent to discerning consumers and vastly reduced mevushal wine’s appeal outside Jewish circles.

Wine commentators universally panned mevushal processes as damaging to wine, no matter how carefully it was done. Few were as blunt as Jay McInerey, who advised wine buyers “to look at the label, and if the label is mevushal, pass it over. Walk on by. Or, better yet, run.” Even Israeli wine critic Daniel Rogov, with evident sympathy for kosher wines, nonetheless wrote that, with “very few exceptions,” mevushal wines “are incapable of developing in the bottle” and unfortunately often impart “a ‘cooked’ sensation to the nose and palate.” Non-mevushal kosher wine did not encounter the same disdain. The same commentators who heaped abuse on mevushal wines exempted non-mevushal wines from their complaints. McInerey (presumably having run away from wines with a mevushal designation) had only the highest praise for Israel’s Yarden, whose wines of “real distinction and character” were good enough “to tempt the heathen palate.”49

The very success of the relatively small number of non-mevushal wines, however, only entrenched mevushal wine’s status as kosher’s poor cousin. Winemakers unintentionally reinforced this distinction by generally placing lower quality—and hence less expensive—vintages in their mevushal line. “Bad wine pasteurized is still bad wine” Weir complained; making it so created “a self-fulfilling prophecy” that mevushal wine was “the worst wine in the winery.” The economics of the kosher wine business drove this practice. Since mevushal wines were intended for use in social settings, especially large events where the sponsors chose the wine rather than those who actually drank it, less expensive wines were the clear choice for this purpose. And since mevushal wines could not achieve the same prices as non-mevushal varieties, it did not make sense to use better vintages for these occasions. Instead, more expensive, non-mevushal wines were more likely to be drunk by observant Jews in private settings where the presence of a non-Jewish wait staff was not an issue—and where the higher price point was a less important concern.

Kosher wine advocates sought ammunition against critics by supporting research challenging the “anti-mevushal” consensus. With funding provided by several kosher wine companies, University of California-Davis graduate student Shlomo (also Shiki) Rauchberger conducted taste tests to see if a panel of judges could discern the difference between mevushal and non-mevushal Cabernet Sauvignon. Sampling included a recently bottled Cabernet and one aged for one hundred days; in both cases the panel could not taste the difference. As his 1992 study remains unpublished either in print or on the Internet, its methodology could not be reviewed, leading many oenologists to question its veracity. As some pointed out, aging wine just over three months was hardly enough time to test the mevushal process’s effect on a wine’s maturation after bottling. Nonetheless, Rauchberger’s study has lived on as an asset for pro-mevushal positions, morphing from an unpublished paper prepared by a graduate student with industry funding into a study graced by the salubrious lineage of coming from “one of the top wine-making schools in the United States.”50

The spin on the Rauchberger paper did not convince critics; but diligent efforts by kosher winemakers did soften a few hearts—and even palates. Daniel Rogov endorsed Hagafen’s mevushal wines as “among the very best kosher wines anywhere” and thus as proof that “in some cases” the mevushal process was not harmful. Even Jay McInerery granted that among the wines on Kedem’s Baron Herzog label there were a few mevushal varieties (such as its “outstanding” Special Reserve Chardonnay) where there was “little, if any, deleterious effect on the finished wine.” In these cases the great care with which winemakers deployed flash pasteurization technology allowed their mevushal wines to pass muster.51

Kedem was able to ride the Jewish component of the remarkable increase in dry wine consumption after 1980; David Herzog, in that respect, was as insightful as Meyer Robinson in seeing and pursuing new opportunities and, in so doing, built a thriving and dynamic company.

Such success, however, did not alter the broad consensus among wine authorities—and wine consumers—that kosher wine was, in general, inferior to nonkosher varieties. Disdain among tastemakers for the sweet Concord wine of Manischewitz cast a long shadow, and the muttering about cooked mevushal wine hindered any dramatic reversal of attitudes. Not surprisingly, then, the new dry kosher wines did not generate much interest outside the Jewish market. A large New York purveyor of kosher wines admitted in 2008 that “his clients instinctively go to the non-kosher section when they want to buy first-rate wines.” His few “converts” to dry kosher wine tended to be Reform Jews who wanted to support the “kosher movement.”52 The kosher designation may have helped kosher wine producers gain sales among non-Jews for a generation following World War II, but by the late twentieth century kosher was instead an obstacle to breaking into the gentile marketplace.

PASSOVER, AGAIN

Attending my mother’s 2010 Passover Seder, the last one before her death, we were able to enjoy a wide range of kosher wines to complement our meal. After getting ready for the service with glasses of slivovitz, we experimented with several French Burgundies and a California Cabernet as we celebrated, in the way we had for forty years, the Jewish exodus from Egypt. Elijah certainly would have had a fine wine to sip if he entered when we opened the door for him, certainly better than the days when Manischewitz or Mogen David filled his cup. And with the discussion naturally turning to my kosher food book, which seemed to be taking so long to complete, my mother reflected on the extensive selection of kosher wine in her neighborhood liquor store.

The family Seder moved to my southeastern Pennsylvania home after her death in 2011; obtaining kosher wine for those events was a far different experience than in Manhattan. Pennsylvania’s state liquor stores in my area scarcely seemed to notice the existence of dry kosher wine, and the private wine stores in nearby northern Delaware relegated kosher wine to an obscure section in the back where it battled organic and local wines for shelf space. Kedem’s Baron Herzog reds were for sale and offered a welcome alternative to Manischewitz, but it is doubtful that the stores’ non-Jewish patrons even noticed that kosher wine was available unless they stumbled across it looking for other unusual varieties defined by how they were made rather than where they were from.

My personal experience indicates how kosher wine’s great contemporary success providing quality wine for the Jewish market took place alongside its marginalization in non-Jewish circles. Sales figures, to the extent available, show that dry kosher wine was far less able than Manischewitz and Mogen David to attract non-Jewish consumers. While Kedem does not make its annual sales public, journalistic accounts give a rough picture in 2010: around 1 million gallons of grape juice, 1.5 to 3 million gallons of traditional Concord grape wine, .5 million gallons of dry kosher wine from its Oxnard plant, and an unknown quantity imported from its many international affiliates. Taking the highest estimates and assuming that imports were equal to Kedem’s entire domestic production of dry kosher wine gives annual sales of 5 million gallons—half of total kosher wine production in the early 1950s and far less than Manischewitz’s peak output of 13 million gallons in the late 1970s. Indeed, industry estimates in 2010 of a $28 million national market for kosher wines are still less than half the value of Manischewitz’s wine sales in 1979—even if the effect of inflation is ignored.53

Kosher wine’s visibility faded even more dramatically than its consumption by non-Jews. A 1957 survey of five hundred people in New York City, Los Angeles, and Detroit, composed equally of Jews, white gentiles, and African Americans, showed an astonishing awareness of Manischewitz: 72 percent recalled seeing a Manischewitz advertisement on television, almost half had heard a radio spot, and one-third remembered a newspaper advertisement.54 Such prominence allowed Manischewitz to be invoked in comedy routines, songs, and even by an astronaut standing on the moon. Indeed, its cultural presence remains strong enough for Lauryn Hill to feel confident listeners would understand the lyrics “Now I be breakin’ bread sippin Manischewitz wine” in her 1998 apocalyptic ballad “Final Hour.”

Kosher wine’s evolution from sweet to dry is thus not a simple story of “success.” Every Passover, newspaper recommendations for Passover wines contain a similar refrain—once we suffered with Manischewitz, but now we need not suffer anymore with the many good kosher wines available. The story of my family’s switch from Manischewitz is regularly echoed in other writers’ recollections and indeed constitutes a tried and true narrative for how kosher wine is better than it used to be. Such an argument usually is discursively connected to the wider success of kosher food in the past twenty years as a type of product appealing not only to observant Jews but also to middle-class consumers who believe that kosher certification makes the food better—healthier, safer—than nonkosher varieties.

FIGURE 6.5 Rabbi and Meyer Robinson at Monarch Wine. Collection of Gale Robinson.

Such a narrative hides in plain sight the remarkable achievement of Manischewitz wine as the first crossover branded kosher product. It was so successful in American culture that 80 percent of its customers in the mid-1950s were not Jewish—even though it was an aggressively kosher product. With such dramatic accomplishments, why isn’t Manischewitz considered a kosher success story? Why is it a negative reference point, its very rejection by Jews and other Americans a sign of progress?

Manischewitz’s success, very simply, disrupts the narrative offered by contemporary promoters of kosher food who stress its attraction to consumers with disposable income willing to pay more for food that seems healthier—especially the white middle-class consumers who also buy organic foods for the same reason. These were not the people who made kosher wine so popular. Instead, Manischewitz’s remarkable appeal was principally to African Americans, not middle-class whites. Seeing blacks as a market for kosher products is not part of this narrative—for that matter, neither is a wine favored by Sammy Davis Jr. as well as blue-collar African American men kicking back after a day of work.

That said, there is an additional complication to the “success” story of dry kosher wine—the enduring antipathy among non-Jewish white Americans. White gentile consumers were never particularly interested in kosher wine, even when they drank sweet Concord grape products that differed little from Manischewitz, instead preferring brands not associated with Jews. With the widespread growth of kosher varieties since 1985 that are easily as good as conventional dry wines, the kosher designation nonetheless continues to carry a stigma. Such deep-seated attitudes suggest that the integration of kosher food with American culture remains fraught, with a troubling incompatibility remaining between some Jewish ritual food practices and mainstream American culture. Kosher wine’s challenges, however, would find an even deeper resonance in the difficult saga of kosher beef, detailed in the next two chapters.