All of us know that the calibre of talent distinguishes great from good, winners from losers and adaptation from extinction. Having the right team playing on the field is the fundamental difference between victory and defeat.

Indra Nooyi, chairman and chief executive, PepsiCo

SOME 15 YEARS AGO, McKinsey & Company, a global management consulting firm, produced a now famous report called The War for Talent. It made the case that international companies needed to pay as much attention to how they managed their brightest employees as they did any other corporate resource. McKinsey declared that “better talent is worth fighting for” and predicted a world where the supply of talent would decrease while demand would rise. Companies would be locked in a constant and costly battle for the best people for the foreseeable future.

McKinsey’s definition of talent went far beyond managerial or leadership skills:

[Talent is] the sum of a person’s abilities … his or her intrinsic gifts, skills, knowledge, experience, intelligence, judgment, attitude, character and drive. It also includes his or her ability to learn.

In response to economic boom times between 1998 and 2001, many firms expanded rapidly and the battle to recruit and keep the best people well and truly began. The talent management function, as well as a burgeoning talent management industry, sprang up to identify, retain and develop high-flying individuals into a small, exclusive top tier of managers and leaders.

Despite several cycles of economic boom and bust, as well as the world’s most severe economic crisis, the battle for talent continues. The competition for the best staff has broadened beyond senior leadership talent. Employers are struggling to recruit sufficient numbers of highly skilled people for a wide variety of managerial and specialist positions.

At the international level, talent shortages are more severe. During the past decade, an internationally mobile group of employees, who can pick and choose where they work, has emerged. As firms in emerging markets also begin competing in the global economy, these people are in ever-greater demand.

Singapore, for example, has embarked on an intensive recruitment programme for skilled foreign workers, with more liberal criteria for eligibility to work in the country. Some 90,000 now work in the city-state, the majority from the United States, the UK, France, Australia, Japan and South Korea.

The World Economic Forum predicts good times ahead for this internationally mobile group. In its 2012 report, Stimulating Economies Through Fostering Talent Mobility, which analyses the demand and supply of skilled workers in 22 countries and 12 industries, it comments:

The coming decades will present golden opportunities for well-educated people with critical expertise. So deep and widespread will be the talent gap that individuals willing to migrate will have unprecedented options.

Annual surveys of employers worldwide between 2009 and 2013 by ManpowerGroup, a multinational human resources consulting firm, have shown steady rises in the number experiencing difficulties in recruiting skilled workers. The 2013 survey revealed that more than a third (35%) of nearly 40,000 employers worldwide are experiencing difficulties in filling vacancies. One in three employers in the United States is experiencing skills shortages; European employers are reporting similar shortages. Despite continued high unemployment in many European countries, especially those in the euro zone, more than one in four employers (26%) struggle to fill jobs because of talent shortages. Around three-quarters (73%) of responding firms say the main obstacle is a lack of people with the right level of experience, skills or knowledge to fill these positions.

Firms in the survey report the highest shortages since 2008, and over half (54%) believe that this will have a “high or medium impact” on their competitiveness. This is an increase from 42% in 2012. The jobs that are most difficult to fill include engineers, sales representatives, technicians, accounting and finance staff, managers and executives and information technology staff.

Jeffrey A. Joerres, ManpowerGroup’s chairman and CEO comments:

There is a collective awakening among the surveyed firms about the impact of talent shortages on their businesses. Globally, employers are reporting the highest talent shortages in five years. Although many companies recognise the impact these shortages will have on their bottom line, more than one in five is struggling to address the issue.

The Chartered Institute of Professional Development (CIPD)/Hays 2013 Resourcing and Talent Planning survey in the UK shows a threefold increase in the number of employers reporting difficulties in recruiting well-qualified people, from 20% in 2009 to 62% in 2013 (based on the responses of 462 UK-based HR workers). Managerial and professional vacancies are the hardest to fill (52% of responding employers said this) followed by technical specialists (46%), particularly in the manufacturing and production sector.

However, the CIPD/Hays survey revealed that some of the difficulty in recruiting is because skilled workers are reluctant to move jobs during a time of economic uncertainty. It shows that the rate of labour turnover has declined steadily since the start of the financial crisis in 2008. One in six organisations reported that a shortage of skilled job applicants has contributed to recruitment difficulties.

A phoney war?

Employers certainly think they are experiencing talent shortages, but is this really the case? Is the current difficulty in recruiting skilled workers more to do with their reluctance to move jobs than any real decrease in their numbers?

There is an argument that genuine talent shortages would lead to rising wages and lower rates of unemployment for skilled workers such as university graduates. Yet few developed countries are seeing any rise in wages and unemployment rates have risen in many of them.

Mark Price, a labour economist at the US-based Keystone Research Center, points to the number of manufacturers complaining about the shortage of skilled workers in the United States. In 2011, there were reportedly 60,000 vacancies in qualified skilled posts within the US manufacturing sector. “If there’s a skill shortage, there have to be rises in wages,” Price says. “It’s basic economics.” Yet the evidence from organisations such as the US Bureau of Labour Statistics is that wages have either stalled or are even falling in the manufacturing sector.

Business leaders, policymakers and economists in the United States have had a vigorous debate about the possibility of a phoney war for talent. A notable figurehead for those who doubt the claims of serious skills shortages is Peter Cappelli, professor of management at the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. In his 2012 book Why Good People Cannot Get Jobs, he argues that there is no real shortage of skilled workers. He believes that the problem is a result of poor recruitment practices and “picky” employers who make unrealistic demands on workers and offer too low pay. He asserts:

The skills gap story is their [employers’] diagnosis. It’s basically saying there’s nobody out there, when in fact, it turns out it’s typically the case that employers’ requirements are crazy, they’re not paying enough or their applicant screening is so rigid that nobody gets through.

Searching forever for somebody – that purple squirrel, as they say in IT, that somebody who is so unique and so unusual, so perfect that you never [find] them – that’s not a good idea.

Cappelli points to other practices that help suggest skills shortages. American employers, he argues, are placing too great an emphasis on work experience and are turning away qualified and trained candidates. They are unwilling to provide these candidates with the training or skills that would help alleviate apparent talent shortages. Unrealistic “wish lists” are configured into applicant tracking software, again leading to the rejection of qualified candidates.

He also argues that employers are often leaving positions vacant, parcelling out the work to other employees. This is because most internal accounting systems do not help organisations calculate the true cost of unfilled positions, and there is an impression that there is an economic benefit from not filling jobs.

Research by Randstad, a multinational human resources consulting firm based in the Netherlands, confirms that external recruitment processes are taking longer and that employers are choosier. In the UK, for example, successful candidates for senior roles undergo an average of 3.4 interviews, compared with 2.6 in 2008, and for junior roles an average of 2.4 interviews, compared with 1.6.

Psychometric testing is one major reason for lengthening appointments processes. Randstad’s survey finds 29% of UK roles now involve some form of psychometric, technical or aptitude testing, compared with 14% in 2008. Vetting candidates, such as checking references and qualifications, delays the hiring process by 15.2 days on average.

Mark Bull, Randstad’s UK chief executive, says that employers have become increasingly selective when it comes to interviewing:

Prospective employees have to jump through many more hiring hoops today than they did before the recession. Employers are often looking for more bang for their buck. A skill set that was satisfactory five years ago might not be now, as employers look towards the long-term potential of new hires. It’s not enough to demonstrate you can do the job being advertised – you need to show you can develop in the role and bring something valuable to that organisation in the future.

ManpowerGroup has also noted this trend but nonetheless believes there are real talent shortages. Its 2013 survey suggests that “sluggish demand is actually exacerbating talent shortages”. Companies are being more selective about potential hires, seeking an exact match instead of taking the time to develop the skills of less-qualified applicants. Weak demand is effectively clogging up the system. The survey concludes:

If demand for their products and services was more robust, [employers] would not have the same luxury of time – hence the apparent head-scratcher of listless jobs growth and greater skills shortages.

Is it possible to reconcile static wages and large numbers of unemployed people, including university graduates in many European countries, with the complaint from business that they cannot find sufficient numbers of skilled workers? The answer, provided by Hays, a UK recruitment company, and Oxford Economics, a global forecasting and analysis company, is that wage pressure and unemployment rates are not accurate indications of skills shortages. Several factors need to be taken into account to understand the market for skilled labour. Hays and Oxford Economics pooled their data to identify seven “components” that together give a better picture of skill shortages:

- Labour-market participation. The degree to which a country’s talent pool is fully utilised; for example whether women and older workers have access to jobs.

- Labour-market flexibility. The legal and regulatory environment faced by business, especially how easily immigrants can fill talent gaps.

- Wage pressure overall. Whether real wages are keeping pace with inflation.

- Wage pressure in high-skill industries. The pace at which wages in high-skill industries outpace those in low-skill industries.

- Wage pressure in high-skill occupations. Rises in wages for highly skilled workers are a short-term indication of skills shortages.

- Talent mismatches. The mismatch between the skills needed by businesses and those available, indicated by the number of long-term unemployed and job vacancies.

- Educational flexibility. Whether the education system can adapt to meet the future needs of organisations for talent, especially in the fields of mathematics and science.

With these seven measurements Hays and Oxford Economics created a “global skills index”, which they used to analyse the market for skilled labour in 27 key economies across all five regions of the world during 2012.

The result was a clear picture of skills shortages in 16 of the 27 countries. The study concluded that despite rises in unemployment around the world, particularly in North America and Europe, there is “little evidence that this has led to an easing in skill shortages. Indeed, evidence seems to point to a worsening of the situation”. Even though wage pressure is weak in the United States, the UK and Ireland, these countries are experiencing the greatest degree of “talent mismatch”, where companies are struggling to recruit the skills they need, despite a large pool of available labour.

The index reveals that skill shortages occur for varied reasons within countries. For example:

- Germany has the highest overall score for skill shortages and is experiencing wage pressures for high-skill industries and occupations; the engineering, IT, utilities and construction sectors have been particularly hard hit. There is an estimated shortage of 76,400 engineers and 38,000 IT professionals.

- France is experiencing skill shortages for different reasons. Labour-market inflexibility is stopping firms recruiting foreign talent, and there is a “talent mismatch”, where skilled workers are opting for jobs in the financial and commercial sectors instead of sectors such as engineering where there are skill shortages.

- The UK is experiencing skill shortages in sectors such as energy, banking and finance. It has one of the highest scores for talent mismatches, suggesting there is a serious gap between the skills that employers need and those available in the labour market. However, this is not leading to a rise in wages, as the UK’s relative openness to migrant labour is enabling employers to attract staff from overseas (although recent changes in employment laws suggest the country is becoming less welcoming).

- The United States has the highest overall score for skill shortages. There is a strong demand for skilled people in the oil and gas industries, life sciences and information technology. A big problem is a shortage of experienced and skilled workers but an oversupply of people at entry level. Large numbers of people are either unemployed or underemployed in semi-skilled and part-time jobs because of a lack of skills.

Overall, the index provides evidence of both genuine skill shortages and “talent mismatches”. Hays and Oxford Economics conclude:

It is clear from our report that while many graduates are out of work, particularly in Europe, at the same time the world is chronically short of particular skills … Some of the most important skills for driving growth are in shortage on a global basis …There is a serious disconnect between higher educational bodies, employers and graduates about the skills now needed in the workplace.

Demand for more advanced skills

Part of the problem for organisations and employees is that new and increased skills are required in the workplace. As economies move from being product-based to being knowledge-based, the number of specialist jobs increases. It is hard for employers and educational providers to anticipate these changes. By 2020, the European Centre for Vocational Training predicts that 81% of all jobs in the EU will require “medium and high level qualifications” because of the continuing shift towards knowledge-intensive activities.

Firms operating in knowledge-intensive industries depend on their most capable staff to help create value through intangible assets such as patents, licences and technical know-how. This is asking a lot. To operate at this level, many people need not just specialist knowledge or technical skills, but also higher cognitive skills to equip them to handle the intricacies of decision-making and change.

The twin forces of globalisation and technology have also led economies across the world to become more entwined, adding to the complexity of many jobs and occupations. Firms are now looking for individuals with a range of abilities that might include specialised skills, broader functional skills, industry expertise and knowledge of specific geographical markets.

Four broad areas of skills will be in greatest demand over the next ten years, according to Oxford Economics and Towers Watson, a global professional services firm. Based on a worldwide survey of 352 human resources managers in the first quarter of 2012 and a modelling exercise involving 46 countries and 21 industry sectors, employers will place a premium on the following:

- Digital skills. The fast-growing digital economy is increasing the demand for highly skilled technical workers. Companies are looking for staff with social-media-based skills, especially in “digital expression” and marketing literacy. Digital business skills are rated as crucial, particularly in Asia-Pacific, where e-commerce is expanding rapidly as the result of a “new digital technology war” among firms.

- Agile thinking. In a period of sustained uncertainty, where economic, political and market conditions can change suddenly, agile thinking and scenario planning are vital. Those respondents from industries with high levels of regulatory and environmental uncertainty, such as life sciences and energy and mining, highlighted the importance of agile thinking. Respondents said that the ability to prepare for multiple scenarios is especially important. HR managers also put a high premium on innovative thinking, dealing with complexity and managing paradox.

- Interpersonal and communication skills. Overall, HR managers predict that co-creativity (collaborating with others) and brainstorming skills will be greatly in demand, as will relationship building and teamwork skills. Oxford Economics points out that this reflects the continued corporate shift from a “command-and-control organisation to a more fluid and collaborative style”. As companies move to a “networked” corporate world, relationships with suppliers, outsourcing partners and even customers will become more dispersed and more complex. It will take skill to manage these networks and build consensus and collaboration with network partners.

- Global operating skills. The ability to manage diverse employees is seen as the most important global operating skill over the next 5–10 years. In the United States, the top global operating skill was understanding international business. According to Jeff Immelt, chairman and CEO of General Electric, employees need skills in both “glocalisation” (where home-market products and services are tailored to the tastes of overseas customers) and reverse innovation (where staff in emerging markets lead innovation and then the company applies these new ideas to mature markets).

McKinsey’s research suggests that this “skill inflation” is occurring in many jobs. There has been a significant increase in the number of jobs involving “interaction work” in developed economies – that is, non-routine jobs involving intensive human interactions, complex decision-making and an understanding of context. In the United States, for instance, some 4.1m new jobs involving interaction work were created between 2001 and 2009, compared with a loss of 2.7m “transaction”-based jobs, where work exchanges are routine, automated and often scripted.

The quantity and quality of graduates

Countries are not producing sufficient numbers of highly educated people to keep pace with the needs of employers and to sustain economic development. This is the case in both emerging markets and developed economies, as an analysis of the global labour force by the McKinsey Global Institute in 2012 shows. The research, covering 70 countries which account for 96% of global GDP, suggests a global shortfall of 38m–40m college-educated workers by 2020.

Although the rate of “tertiary educational attainment” has doubled since 1980, advanced economies (some 25 countries with the highest GDP per head in 2010) will have 16m–18m too few graduates by 2020. Demand is likely to outstrip supply because of the expected expansion of knowledge-intensive sectors in advanced economies. In the United States, the gap could reach 1.5m graduates by the end of this decade. Even China, which has rapidly expanded tertiary education, is forecast to have a shortfall of 23m graduates by 2020.

There is as much a problem with the quality of graduates as their quantity. Work by the World Economic Forum (WEF) shows a growing problem of employability among graduates in many countries. Employability is defined as the skills graduates need to gain employment and work effectively in a company. These include technical skills, industry-based skills and more generic soft skills such as adaptability, time management and the ability to communicate well.

Employers in a number of countries (including China, Russia, Brazil, Italy, Spain and Turkey) expressed concerns about the level of employability of graduates. In China, for example, although 6.4m students graduated in 2009, 2m were still looking for a job one year later. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences reported that many of these students lacked the skills required by employers.

Only a small number of graduate schools in India comply with international standards. According to the International Institute for Labour Studies, only 25% of Indian graduates and 20% of Russian graduates are considered employable by multinationals. The WEF says there is an urgent need for governments, educational institutions and employers to collaborate to provide graduates with more relevant education and training. But if graduates are to keep pace with changes in the workplace, employers need to help them keep learning and developing throughout their careers.

Demographic trends

Changing demographics are likely to cause substantial shifts in the size and age of workforces around the world. Employers will need to take account of these shifts when they draw up their plans for “sourcing” talented workers, as well as how they manage their existing pool of talented employees.

The war for talent will intensify, given that the global workforce is predicted to decrease over the next two decades at a time when the demand for advanced skills is expected to increase substantially as a result of globalisation and advances in technology. The WEF warns that “the global economy is approaching a demographic shock of a scale not seen since the Middle Ages”. It predicts that by 2020, for every five workers who retire, only four young workers will enter the workforce in the majority of OECD countries.

For the first time ever, the EU’s working-age population (aged 20–64) is decreasing from a peak of 308.2m in 2012. The number of workers is likely to drop to 265m by 2060. These demographic shifts, which may be tempered by people working longer, would be even bigger but for an assumed net inflow of over 1m (mostly young) migrants a year.

Ageing populations, especially in North America and Europe, will lead to large numbers of experienced workers retiring, with a corresponding loss of skills and experience. According to the US Census Bureau, 10,000 Americans will retire every day between 2010 and 2030. And according to the European Commission, on average, Germany, France and Italy have the oldest population. Germany’s declining birth rate, which now stands at 1.38 children per women, has led to predictions of an economic decline in the next two decades.

An ageing population could offer new possibilities for employers and skilled workers, but it could also create a new set of problems. There could be a new willingness to retain the skills of older workers. In the United States, Germany and Italy, there is active consideration of how skilled older workers can be encouraged and supported to continue working. For example, Germany’s Cologne Institute for Economic Research recently urged employers to build more attractive working environments to retain employers aged 55 and over. This might require redesigning roles and taking into account health-care benefits as much as pay.

Conversely, employers might find that retaining older workers blocks the career development of younger employees. There is also the possibility that lower-paid employees (who are likely to be less skilled), rather than their more skilled and better-paid peers, will want to take up any offers of continuing employment. The Pew Research Center, an American think-tank, suggests that six in ten of American workers aged between 50 and 61 may have to postpone retirement because they cannot afford to stop work, but just how their wishes can or will be accommodated by employers remains to be seen.

Employers may still have some way to go before they think about older workers as a valuable source of talent. Research from both sides of the Atlantic suggests that employers are reluctant to recruit unemployed older workers, even qualified and experienced ones. Age discrimination is cited as one likely reason that, in the first quarter of 2012, 40% of older unemployed workers (aged between 50 and 59) in the United States had been out of work for a least one year.

In the UK, a 2013 study by the Age and Employment Network covering 729 unemployed workers explored the reasons why they could not obtain full-time work. It concluded that “age discrimination” is rife among employers. Many of the respondents were highly skilled: 47% were managers or senior officials; 43% had a degree or an equivalent qualification; and 57% had some kind of professional qualification. Despite their experience, 18% of the respondents had been unemployed for 6–12 months, 19% for more than one year and 31% for more than two years.

Insufficient skills did not appear to be a problem; three out of four respondents said they had the right skills for their occupation and industry, with managers and officials being most confident. However, the most significant factor affecting their ability to get work was the attitudes (or prejudices) of employers – 83% said recruiters viewed them as too old, and 72% said they saw them as “too experienced or overqualified”.

Working populations are also becoming more ethnically diverse, and this may also require employers to confront assumptions or prejudices that might stop them tapping into this growing pool of talent. In the United States, if current trends continue, the demographic profile of the workforce will change dramatically by the middle of this century, according to new population projections developed by the Pew Research Center. It predicts that the population will rise from 296m in 2005 to 438m in 2050, and that new immigrants and their descendants will account for 82% of the growth. Of the 117m people added to the population through new immigration, 67m will be the immigrants themselves, 47m will be their children and 3m will be their grandchildren.

Talent management to the rescue?

There seems no doubt that highly capable employees are in short supply and that employers must make strenuous efforts to find them, keep developing their abilities and make sure that they are not poached by rival firms. Are talent management strategies up to the challenge?

Research for this book reveals that there is an established approach to making the most of gifted employees, but it is beginning to look outmoded and ineffective in the face of the global fight for talent. There is evidence that senior managers and HR managers are highly dissatisfied with their talent programmes, and are looking for new ways to make sure that high-flying employees are identified and nurtured.

During the past decade a model of good practice has been developed which most organisations with a reputation and track record of success in this field try to follow. This model encompasses:

- Links to graduate entry schemes. For decades before the term was commonly used, talent management strategies have been closely linked to graduate entry schemes with selection processes (often assessment centres, psychological tests, etc) designed to spot potential talent.

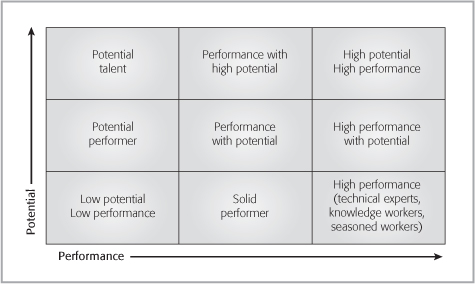

- Early identification of potential and performance. Even if this does not occur at graduate entry levels, early identification of both potential and performance form part of most talent management strategies. A popular and commonly used tool to achieve this is the “nine-box grid” (see Figure 1.1), often used in a group setting, which provides multiple perspectives of employees’ skills and potential.

- Targeted and tailored support, development and career planning. Once “talented” individuals have been identified, they receive targeted and tailored support development and career planning. This may include study opportunities on sponsored MBA or other postgraduate programmes, senior management development programmes (delivered either internally or at prestigious business schools) and systematic cross-disciplinary and cross-geography job rotation to make sure that individuals have management experience in key functions connected to the business strategy. In recent years, particularly in the case of women and ethnic minorities, personalised career management has been supported by coaching, mentoring and the use of “sponsors” (senior managers who champion an individual for promotion).

- Long-term succession planning linked to talent “pipelines”. Roles filled through this talent “pool” are planned sometimes decades in advance through a complex system of succession planning and talent “pipelines”. The progress of individuals towards their allotted roles is reviewed regularly (often on a quarterly or twice-yearly basis) by talent review committees made up of a combination of specialist HR managers, line managers and members of the senior management team. Often the organisation’s chief executive or other board members chair these committees. This ensures that the roles under scrutiny are linked closely to the requirements of the business strategy and the wishes of stakeholders and shareholders (institutional shareholders are now looking closely at organisations’ succession-planning processes when making investment decisions).

- Exposure to senior management. Often with the backing of the chief executive, prospective candidates for senior roles in the talent pipeline are systematically exposed to the organisation’s existing senior management through formal and informal briefings, workshops and discussion groups. Ensuring that this occurs has become an important role for the chief executive (see Indra Nooyi’s comments in chapter 2).

A 2011 CIPD report provides a snapshot of talent management approaches in UK-based businesses:

- Talent management activities are most commonly focused on two groups – high-potential employees (77% of responding firms said this) and senior managers (64% of responding firms).

- Small and medium-sized firms (SMEs) use talent management more than do larger organisations (more than 250 employees) both to attract key staff (41% of SMEs compared with 20% of larger firms) and to retain them (50% of SMEs compared with 35% of larger firms).

- Some 77% of very large firms (more than 5,000 employees) have talent management programmes, and some 66% of them focus their efforts on senior managers.

Talent is a relative concept

By and large, companies formulate their own definitions of talent and potential. It is safe to say that talented people are highly intelligent and gifted, with a particular blend of skills, knowledge and personal attributes. However, most organisations define talent in the context of their business or industry. Individuals are given the label of talented because they have attributes that are of great value to the business and hard to develop or replicate in others.

The firms featured in the case studies in this book have their own definitions of talent, but the common focus is on individuals who either make, or have the potential to make, a disproportionately strong impact on their part of the business. In other words, their knowledge and skill make such a difference that their organisations can ill-afford to lose them.

In some of the case studies, a star employee is someone with rare specialist skills. These skills are in great demand in the labour market and rival companies may be trying to poach these individuals. However, the majority of the case studies focus on leadership ability, and the firms featured arrived at a definition of talent by identifying key roles in the organisation that needed to be filled by the most capable individuals in the immediate or medium-term future (that is, succession planning).

Organisations have different talent requirements, which mirror the size and complexity of the business. These definitions or “talent profiles” effectively segment talent and form the basis of different talent pools. These could include, for example:

- technical specialists, especially in areas key to the organisation’s core capabilities;

- individuals with hard-to-recruit skills;

- bright individuals from underrepresented groups whom the organisation wishes to advance into more senior positions;

- the best-performing graduates or school leavers;

- managers with the potential to move into senior management positions at the local, national or international level.

Regardless of the mix of specialist and management/leadership skills, talent is usually defined in terms of exceptional performance or high potential. The weighting of these two attributes is decided by senior managers in line with the organisation’s immediate and long-term priorities. There is often an implicit judgment about selecting individuals whose behaviour and values fit with those of the organisation.

How performance and potential are measured is for senior managers to decide. In many cases, the definition of exceptional performance is laid out in competency frameworks and appraisal systems. Defining high potential can be more difficult and might include a range of assessment tools such as development centres, psychometric testing and, inevitably, the personal judgment of those whose insights into talent are widely respected.

Organisations often use a nine-box grid to map individuals in terms of potential and performance (see Figure 1.1). Existing performance-management processes will be relied upon to keep monitoring and improving the performance of weak or solid performers. Technical specialists are often grouped in the bottom right box and the organisation, while valuing them highly, may not feel they need any extra opportunities to fulfil their potential. A talent management programme will generally focus on individuals in the top right box.

Some organisations opt for the simple solution of automatically placing a percentage of its top performers, identified through existing appraisal processes, into a talent pool. At Network Rail, for example, the talent pool was created for individuals who had reached the two uppermost bands for senior managers. However, the company has other selection criteria. Managers must be capable of moving up an additional band (into the highest senior management band or the director-level band) and be capable of moving across Network Rail as well as upwards. Approximately 100 managers constitute the talent pool at any one time.

Other organisations favour informal approaches to defining talent and identifying high-flyers. In an international manufacturing company, there is an informal network of senior HR managers who keep an eye on promising employees. Known as “TalentWatch”, the network both identifies talented individuals and promotes their advancement by ensuring they are allocated to temporary “special projects”, which will stretch them and enhance their personal reputation.

Well-established – but not well done

After a decade of experimentation, many companies still struggle with their talent strategies and are by no means confident that their approaches will guarantee enough leaders and specialists of the right calibre for their current and future needs.

A global survey by the Boston Consultancy Group (BCG) in 2010 suggests that many companies do not have a clear strategy for finding and keeping the best people. Covering 5,561 business leaders from 109 countries, the survey revealed that:

- some 60% of respondents said they lacked a well-defined strategy to source talent or to address their succession challenges;

- more than 33% ranked their company as having no strategy at all, and only 2% cited a strong, comprehensive strategy;

- on average, respondents said their chief executives and other senior managers spent less than nine days a year on activities related to talent management;

- talent management activities were narrowly focused, mainly on high-potential employees, with promising junior employees receiving least attention;

- only 1% of respondents said talent plans were aligned with the company’s business-planning cycle.

BCG concluded that too many companies are “relying on serendipity to meet their current and future talent needs, incurring unnecessary business risk”.

Even human resources managers doubt their own track record in talent management. A 2012 McKinsey study describes HR staff as nearly “paralysed” by the scale of challenges facing them, with many feeling they are failing to keep pace with an unpredictable business environment. They identified talent management as a particularly daunting area. Only 32% had “high confidence” in their talent strategy or actions.

Emily Lawson, head of McKinsey’s global human capital practice, says the uncertainties of the current business environment are making it genuinely difficult for firms to assess the effectiveness of their strategies. She comments:

I can count on the fingers of two hands the robust talent strategies that I have actually seen – where the numbers have been done robustly and are modelled three to five years out where it is clearly understood what it is going to take to compete in a particular market. I think it is very hard.

Talent strategies take a long time to play out. There is still a misalignment between what goes on inside companies and what would strategically benefit them in terms of talent. Also in the wake of the 2008 downturn, companies stopped undertaking a lot of the discretionary activities in areas like career planning and mentoring that play such an important part in the process.

Can talent still be “managed”?

For all this focused investment of time, effort and financial resources, the question remains: can the current model of talent management help companies compete in an intensely competitive and global market for talent?

The research for this book suggests that there are a number of assumptions underpinning the current model that may no longer be relevant, including:

- management and leadership potential can be spotted early;

- this definition of potential will still be relevant in five or even ten years’ time;

- getting to the top young is good for the organisation;

- if you get senior management right, it will help the business;

- career moves can be planned and achieved;

- the concept of systematic development is sound and should be managed by the company;

- the individuals under the spotlight are willing pawns in the game.

The last point is the most important one.

Spotting potential

Taking hard and fast judgments about potential is difficult enough in stable times, but in an unpredictable environment they become risky. As outlined above, the fast pace of change in some industries is making it difficult for firms to anticipate the skills they will need to compete successfully. This is a blind spot for many firms, often because the definition of what constitutes talent is heavily influenced by the existing senior management team. This increases the danger of firms producing an over-homogeneous pool of successors at a time when many experts and simple common sense stress the need for diversity – a theme that is explored in more depth in chapter 4.

Chris Benko, vice-president of global talent management at Merck, an American pharmaceutical company, comments:

Transforming the company and the way we think about talent is very challenging … Most of the formative experiences of our senior leaders were in the late 1990s and the early part of this century – which was a heyday for the pharmaceutical industry.

Now we need to move leaders pass their comfort zones to think about what it is going to take to develop in a way that is contrary to what led to their success and the success of our company.

Some organisations have no time for high-potential development schemes. Liane Hornsey, vice-president of people operations at Google, a multinational corporation specialising in internet-related services and products, says that she “detests” such schemes. Google, by contrast, offers all its employees the opportunity to put themselves forward for promotion based on their track record and performance:

We never hire because we have to get a task done. Every single hire that we make, be that in the most junior of roles, be that in the most junior customer service position for example, we will hire someone who we think has the potential to be a very senior leader.

In firms that adopt this approach, a strong culture that motivates bright employees to put themselves forward for advancement and development plays a far more important role than the detailed systems and processes for talent selection and development. Responsibility for career management and development is shared more effectively between the individual and the organisation. Getting the culture right is crucial, as Hornsey stresses:

Over I don’t know how many years, I have learned one thing. And that one thing is that if you don’t have a fertile soil in which you plant seeds, it doesn’t matter how intellectually robust and how brilliant your processes and your programmes are, they will fail. But if you have a robust soil, and a brilliant culture, the processes and the programmes can be pretty weak but they will work – because having the right culture is absolutely the bedrock to making sure you develop talent.

Talent-based culture is covered in more detail in chapter 5.

Keeping pace with business needs

Traditional talent management has generally focused on an integrated set of activities to make sure that there is a reliable supply of seasoned managers who will form the next generation of senior managers and leaders. Much of the focus of HR staff has been on activities and programmes which, although important, have arguably taken on a life of their own. This is covered in more detail in Chapter 3.

Becky Snow, global talent director at Mars, points out that talent management schemes are like huge tankers that are slow to manoeuvre if the organisation decides (or is forced) to move in different directions at short notice – an increasing likelihood in an uncertain and volatile world (see Chapter 3). Steering this tanker has prevented talent heads from playing a sufficiently strategic role in the business. If companies are to compete for talent effectively, they need to pay much more attention to achieving a tighter alignment between the needs of a business and the product of its talent management strategies. This is explored in more depth in Chapter 2.

Too much focus on the top

Most talent strategies focus heavily on getting a small number of people to the top of the organisation – often at the expense of everyone else. Yet there is less and less of a guarantee that the genuinely talented people the company seeks for its senior roles are willing or eager to invest their lives and their careers in reaching this goal.

Conventional talent management schemes rarely accommodate:

- mavericks and outsiders who are creative and innovative in their thinking but do not perform well using traditional appraisal measures;

- those with entrepreneurial aspirations who are frustrated by the lack of opportunity to engage in business start-up activities or (more cynically) use a corporate career as a stepping stone to launch their own enterprise (in both cases the organisation loses precious skills that it badly needs);

- late starters or those recruited later in their careers who are normally too old to be on the high-flyer track even though they might vary the pool of talent at the organisation’s disposal;

- those in peripheral careers within the company (technology, research, data processing) or those who want to make sideways moves for personal reasons or because they prefer the line of work;

- those who are not sufficiently motivated by the prize on offer to pay the price they have to pay to climb the corporate ladder.

Chapters 4 and 6 explore how talent strategies need to be broadened to appeal to the needs and wants of these largely untapped groups of employees.

Conclusion: willing pawns?

Traditional talent management assumes that high-flying employees want to get to the top of the pile and will do whatever their firms require to get there. However, a new generation of talented workers may not be willing or motivated to stay with one employer for long, whatever the financial rewards and career opportunities on offer.

This makes long-term career planning much more difficult for organisations. Chapter 6 looks at how firms can retain the skills and creativity of former workers through associate and consultancy positions or by creating internal structures that enable intrapreneurs – those with entrepreneurial skills and aspirations who are willing to work inside organisations – to engage in business start-up activity and ideas incubators. These new relationships and work arrangements will help organisations anticipate and respond quickly to changes in the marketplace.

The following chapters look at how firms are changing their talent strategies in a volatile business environment where gifted employees have the ability to pursue opportunities virtually anywhere in the world.