The Southgate Singers: (left to right) Tom Laughon, Paige Pinnell, John Pierson, with unidentified woman holding albums, 1963. Permission of the University of Florida, Smathers Library Special and Area Studies Collections, University Archives.

FROM HOOTENANNY TO A HARD DAY’S NIGHT

1964

“The Banana Boat Song” » Harry Belafonte

“Wipeout” » The Surfaris

“Theme from Dixie” » Duane Eddy

“The Girl from Ipanema”» Stan Getz and Astrud Gilberto

“Surfin’ USA” » The Beach Boys

“Tom Dooley” » The Kingston Trio

“Blowin’ in the Wind” » Peter, Paul, and Mary

“The Lonely Bull” » Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass

“You’ve Really Got a Hold on Me” » The Miracles

Near the end of the fifties, rock and roll music and culture seemed destined to become the passing fad so many adults had predicted or hoped for. Little Richard had found religion in 1957 and joined a seminary, and Elvis was drafted in 1958 and served two years in the Army. When Jerry Lee Lewis casually admitted in a British interview that same year that he would soon be marrying his thirteen-year-old third cousin (Lewis was twenty-two and had in fact already married her), the ensuing publicity caused an uproar, leading to the tour cancellation, while stateside Lewis was blacklisted from radio and was back to playing bars and small clubs.

On February 3, 1959, Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper (J. P. Richardson) died in a plane crash a few miles north of Clear Lake, Iowa. Later in the year Chuck Berry was arrested for being intimate with a fourteen-year-old waitress and then transporting her across state lines, violating the Mann Act and eventually landing Berry in jail. Payola, a record label practice involving the exchange of cash for radio airplay, came under congressional scrutiny in 1959, resulting in the downfall of Alan Freed, one of America’s top DJs and the man who coined the term “rock and roll.”

These were the pioneers of rock and roll, and it began to look like the party was coming to an end. However, despite what Don McLean sang in his song “American Pie,” the music didn’t die the day Holly, Valens, and Richardson did; music simply went elsewhere for a while, mainly just about everywhere.

EVERYWHERE AT ONCE

As the fifties moved into the sixties, varied styles of musical expression rose to prominence in American popular music. The Afro-Caribbean style known as calypso was one trend, presented with great success by singer Harry Belafonte, whose 1956 album Calypso was the first album to sell a million copies in a year, aided no doubt by “The Banana Boat Song.” Day-O!

During the early sixties, songs that instigated and sustained the popularity of various dance styles raced up the charts, including Chubby Checker’s “The Twist” and “Limbo Rock,” Major Lance’s “The Monkey Time,” and the Miracles’ “Come On, Do the Jerk.” Adding to the dance party was Surf music, twangy guitar instrumentals recorded by artists such as Dick Dale (“Misirlou”), the Surfaris (“Wipeout”), and the Ventures (“Walk, Don’t Run”), and vocal pop hits such as “Surfin’ USA” by the Beach Boys and “Surf City” by Jan and Dean. Motown, an independent, black-owned record label out of Detroit, whose slogan was “The Sound of Young America,” was beginning to sell millions of records by black artists such as Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye. Another musical style adding to the general pop music anarchy of the early sixties was Bossa Nova, a blend of Brazilian samba and jazz that became popular worldwide following the release of the Stan Getz and Astrud Gilberto recording “The Girl from Ipanema” in 1964, winning a Grammy for Song of the Year and now the second most recorded composition in pop music history after “Yesterday” by the Beatles.

Frank Sinatra, an artist with roots in the forties, was making best-selling albums with Count Basie and working with a new arranger named Quincy Jones. In 1962 a style of smooth mariachi-inspired Latin jazz was introduced by Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass with “The Lonely Bull.” Movie soundtracks of Broadway musicals topped the charts, and 1961’s “Hit the Road, Jack” was the second number-one song from a Greenville, Florida, musician named Ray Charles, who combined blues, gospel, rhythm and blues, and jazz in a hybrid style of his own invention called Soul.

Blues, Calypso, Twist, Surf, Soul, Motown, Bossa Nova. If it seemed that popular music in America was all over the map during these years, well—it was. But the most popular musical genre among the counterculture at the time, especially on college campuses, was folk music.

KUMBAYA

Folk music is a broad genre built of songs that were handed down from one generation to the next over hundreds of years, transmitted through performance, and usually with no known composer. The folk music revival is distinct from the origins of these songs; it began in the United States in the early fifties and had a strong presence culturally and sales-wise for around a decade. The Kingston Trio was one of the most commercially successful groups of this genre, formed in 1957 as a calypso group and whose first album included “Tom Dooley,” a folk song that sold three million copies as a single. In 1959 the Kingston Trio had four albums in the Top Ten for five consecutive weeks, a feat unmatched to this day. Folk music was hot.

Folk trio Peter, Paul, and Mary, Joan Baez, and the Kingston Trio were established top sellers by 1963. And along came Bob Dylan, whose “Blowin’ in the Wind” was to be a huge hit for Peter, Paul, and Mary in the summer of ’63, topping the record charts and selling more than a million.

The Southgate Singers: (left to right) Tom Laughon, Paige Pinnell, John Pierson, with unidentified woman holding albums, 1963. Permission of the University of Florida, Smathers Library Special and Area Studies Collections, University Archives.

The buzzword for the folk scene was hootenanny, “an informal session at which folk singers and instrumentalists perform for their own enjoyment.” Basically, a hootenanny was a folk music jam session that usually included audience sing-along on the chorus, such as the Kingston Trio’s “Tom Dooley” or Harry Belafonte’s calypso anthem “Jamaica Farewell.” It was tame and pleasant musical fare, but for many adolescent teens seeking an outlet for their hormonal urges and surging youthful adrenaline, folk music was not providing what they were looking for. You could not dance to “Tom Dooley,” merely sway a little and softly sing the mournful lyrics: “Hang down your head, Tom Dooley / hang down your head and cry / poor boy you’re bound to die.” Folk reigned. ABC’s Hootenanny was the only new music program on television that year, broadcasting college folk concerts to eleven million viewers weekly, including one show filmed at the University of Florida that featured Johnny Cash. More than two dozen magazines about folk music were published in 1963, including Sing Out! and Hootenanny. The movie Hootenanny Hoot featured folk singers Judy Henske and Johnny Cash. One Cincinnati radio station went “100 percent hootenanny” and played folk music “around the clock.” An album produced in 1963 of Gainesville “folk artists” featured performances by University of Florida students and faculty members and was called … well, you can guess what it was called.

Folk music had become the de facto protest music of society, as rock and roll had been in earlier years, yet folk lacked what rock and roll had: a driving, danceable beat. Folk music’s rhythm could best be experienced through listening to Peter, Paul, and Mary’s version of Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind,” a recording that also worked well as a lullaby.

Folk music was relatively easy to learn and play, requiring little more than an acoustic guitar, the ability to play a few chords, and a copy of Sing Out!, a popular monthly magazine featuring music articles, songs, chord charts, and lyrics.

But Gainesville and the surrounding areas in midland Florida had a musical heritage separate from this folk music revival. Any road-house with a dance floor and cold beer was just begging for live music, and musicians in the area were there to provide such a service. One such musician was a product of Florida’s musical melting pot.

JIMMY TUTTEN

Jimmy Tutten was playing in and around Gainesville from the mid-fifties through the sixties. Tutten, who grew up in nearby Waldo, now owns a business named Redneck Trailer Sales in Old Town and is a veteran north-Florida musician with an appreciation of black music and culture, particularly the songs of Jimmy Reed, a popular fifties rhythm and blues recording artist, whose songs have been favorites in the South throughout the years.

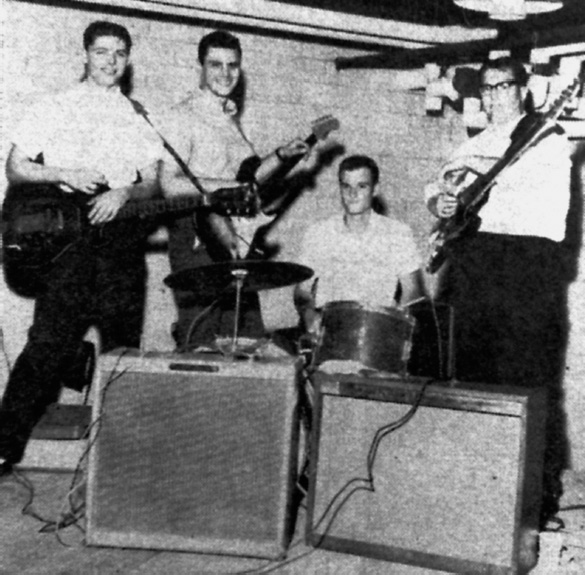

Jimmy and the Rockets, circa 1962: (left to right) Jimmy Tutten, Jim Garcia, unknown, unknown. Permission of Jim L. Garcia. Reprinted from the Independent Florida Alligator.

“The first place I did anything public was the stage at Waldo High School around 1955,” Tutten recalled. “From there we put a group together and played the Recreation Center. Back then I’d written a couple songs. We played Buddy Knox, Little Richard, Fats Domino, all the things that black people came out with, that rock and roll. I liked that music. I always liked the beat of the rhythm and blues that black people had. That was my style, what got me started. Of course you couldn’t play that stuff every place you played. We did it every place we played, but we usually had to play a lot of that other stuff with it. We had about three or four hundred songs we knew when I finally quit. It is a lot of songs. But people would request those songs. Basically, I’d get them off of records, play the records over and over, then you could go to the music store and buy the book that had the words in them. It didn’t take long to learn a song that way.”

Tutten was atypically open-minded in his musical tastes. “We played a combination of rhythm and blues, rock, and some country. I played at Bobby’s Hideaway [in nearby Waldo, Florida] six nights a week. I played a place called the Blue Eagle and for a long time too. It was out in the woods. They were country-western people, and every now and then you’d have a little ruckus out back. I did most of the singing and played the guitar also. I had a Fender and a Gibson, a Fender ‘pork chop’ [Telecaster], and a Fender amp. I liked rhythm and blues and played blues on my guitar, a little blues and some rock. Jimmy Reed, we did just about all his stuff, ‘Honest I Do’ and ‘Bright Lights, Big City,’ songs like that. We were called Jimmy and the Rockets. We played up in Georgia, Daytona Beach, Ocala, at the Rancher [Gainesville farming and ranch supply store]—back in the back of it, we’d set up back there.”

In the early sixties you can already hear the influence of black music on certain white musicians in north-central Florida who bypassed the traditional cultural boundaries separating the two races and who actively pursued listening and playing music alongside black musicians in the black community. Music was doing what it had done since the beginning of time: bringing people together. In Tutten’s words, “I used to go to 5th Avenue and sit in with the black groups there. There was a couple places I played, sit in with black bands. I knew pretty much all the guys that played music there, and they’d tell you, ‘Put your back to the wall so you can see what’s going on in here. Don’t turn your back on nobody in here, except us. We’re OK, we’ll watch out for you.’ Back then when I was doing that, I had a burgundy Gibson Les Paul. That Les Paul weighed twice as much as that Fender ‘pork chop.’ You stand up on the bandstand three or four hours with that Gibson, and you’d know it.

“There’s a lot of respect among musicians. Everybody got along real well together.”

THE CONTINENTALS

Local teenager Don Felder was into the guitar playing of Chet Atkins, early rock and roll, and the blues, especially B. B. King. Felder’s love of music and interest in playing guitar began in the late fifties and kicked into high gear when his father bought him his first electric guitar setup, a Fender Musicmaster and a tiny Fender Champ the size of a lunchbox, later upgraded to a Fender Deluxe amp more suitable for live performance.

Playing electric guitar became his obsession. Young Don practiced nightly after school, shutting the door of his bedroom after announcing that he was “doing his homework”: playing his Sears Silvertone electric guitar un-amplified, so his parents didn’t know what kind of homework he was doing. Felder soon began performing in a weekly talent contest at the State Theatre (506 W. University Ave.), preceding the Saturday kids’ movie matinee of cartoon, serial adventure, and feature movie. Admission was sometimes free with six RC Cola bottle caps.

Despite the impoverished economics of the Felder household, or perhaps because of it, music was a welcome and constant aspect of family life in their small home on NW 19th Lane. Don’s father, Charles Felder, worked at Kopper’s, a lumber treatment facility, and after returning home every night, his one luxury was listening to music from a tape library he had amassed by recording albums borrowed from friends, primarily those of swing bands from the forties.

The Felder family also listened to weekly broadcasts on WSM Radio of Grand Ole Opry out of Nashville, and these sounds complemented Don’s fascination with rock and roll and introduced him to the guitar artistry of Chet Atkins, a regular on the show. Don created his own tape library of songs through borrowing records by Elvis, Buddy Holly, and other dawn-of-rock-and-roll performers and recording them on one channel of his home stereo tape machine, then plugging in and recording his guitar on the other channel, teaching himself the songs by playing along. Felder soon discovered that by tape recording the song at seven and a half inches per second and playing the tape back at three and three quarters, the song dropped in pitch one octave, leaving the song in the same key but now playing at half speed, allowing Felder to figure out difficult guitar passages and solos. In addition to country music and rock and roll, Felder developed a taste for blues guitar from listening to late-night broadcasts from WLAC, a Nashville radio station that featured rhythm and blues music nightly. Both radio stations broadcast with a powerful 50,000-watt signal that could be heard in Gainesville at night and as far away as the Caribbean under proper conditions. The rich musical programming on these two Nashville radio stations, combined with their strong signals, provided inspiration for many southern musicians.

Around 1960 or 1961 a friend told Don of an upcoming local performance by a famous blues guitarist. Felder eagerly agreed to attend, despite rather vague directions as to the location of the venue. Don sat in the passenger seat of the Jeep while his friend drove beyond the city limits in search of the rural locale where B. B. King was playing that night.

“They wouldn’t issue liquor licenses to clubs in ‘Colored Town,’” recalls Felder, “so the promoters would hold these illegal concerts and bars outside the city limits on these farms, and I saw B. B. King play out there when I was about fourteen or fifteen, and me and the kid who stole his dad’s Jeep were probably the only two white guys in the whole place.”

Neither Don nor his friend had the five-dollar admission charge, so they listened and watched the performer from a window. In Felder’s words, “I saw women crying and screaming ‘Tell it like it is, B. B.!’ and him standing there with his Gibson 335 or whatever it was he was playing, plugged into a Fender Super or a Fender Concert set on 10. Every knob was on 10 because I saw it when I walked up to the stage afterwards. And he played four sets, and between each set he’d walk back and sit in the back, which was the horse stall, with bales of hay in it. It was in a real barn. I have no idea where it was; we had to ride in this guy’s Jeep through cow pastures to get there. So I walked in the back door, and there was B. B., and I introduced myself and told him I’d bought this record, and I loved his playing, and he was so nice and kind.”

Felder wasn’t merely a white teenager hanging out at an illegal concert venue consisting solely of African-Americans; he was a very blond, very blue-eyed white guy of Germanic ancestry; in fact, few guys around Gainesville looked whiter than Don Felder. Wasn’t he frightened to be in what must have been an atypical social situation for a teenage kid? “I never had any trouble with anybody involved with that whole music scene, to tell you the truth. There were a couple African-American churches in Gainesville, and I’d go outside on Sunday and listen, and they played guitars and basses and drums; it had a much more energetic spirit in their music than going to the white church and singing the hymns.”

For Felder the next step was as natural as butter on grits. Don formed his band the Continentals, and for the several years of its existence, he remained the one constant as other players came and went, including drummer Jeff Williams, a university freshman who helped the band score coveted fraternity gigs; bassist Barry Scurran, up from Miami; and sax player Lee Chipley. One brief member of this ever-changing lineup was a new kid in town who had lived in Gainesville for a while back in the 1950s. His name was Stephen Stills, and he was looking for a place to stay.

HELLO, I MUST BE GOING

The path of Stephen Stills’s childhood seems to embody what scientists describe as Brownian motion: the random movement of molecules that bounce around, influenced by adjacent particles and influencing ones they encounter. The Stills family was constantly on the move as his father pursued entrepreneurial projects that varied from promoting big band artists to land development. Rather than becoming shy and withdrawn with this constant relocation, Stephen was a well-liked and highly social kid who seemed welcome wherever he went. Equally apparent were his rapidly developing musical abilities, absorbing and assimilating the various musical styles he encountered through his many travels.

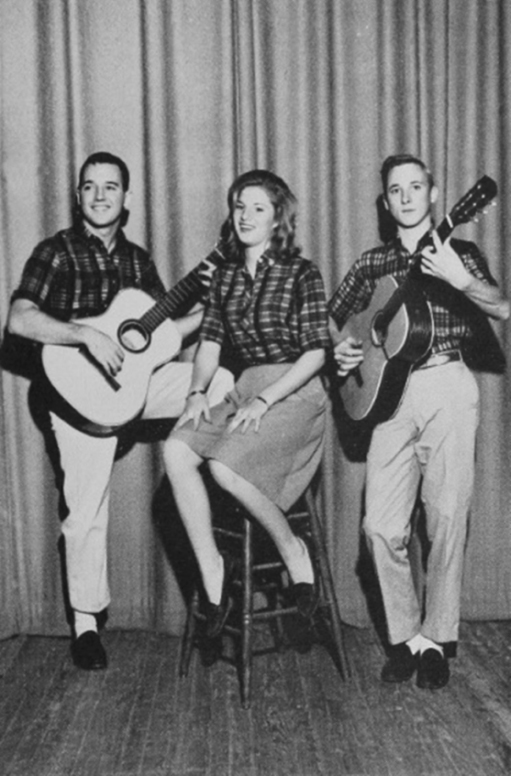

After his initial few years in Gainesville in the fifties, Stills attended Saint Leo Preparatory School north of Tampa and sixth grade at Admiral Farragut Naval Academy in St. Petersburg. He returned to Gainesville briefly during the 1959/60 school year and left Gainesville in 1960 to attend H. B. Plant High School in Tampa. By 1962 Stills was back in Gainesville and enrolled at Gainesville High School as a member of the class of ’63. He is pictured four times in the 1963 GHS yearbook: in his senior photo, playing bass drum in the band, in choir robes front and center in the chorus, and as one-third of a folk group named the Accidental Trio, with classmates Jeff Williams and Nancy Willingham.

Later in the school year he was summoned to Costa Rica by his father to help with a land development project, where Stills attended Colegio Lincoln in San Jose and where he received a certificate of graduation in late 1963. He returned to Gainesville from Costa Rica in the latter months of 1963 and stayed at the Williams home and then at the home of John Scarritt, another classmate. It was mutual friend Jeff Williams who introduced Stills to Don Felder, who recalled Stills as having a rebellious, independent streak and “one of the most distinctive voices I’d ever heard,” and they soon began playing together in the Continentals. Stills had to borrow an electric guitar to play with the group: “I was the drummer first, but Jeff couldn’t play anything. But he could keep time. And he was the one with the car and the mom that was really understanding.”

During the few months that Stills and Felder were both with the Continentals, the group played fraternity gigs (Williams’s older brother was a member of Sigma Alpha Epsilon), a dance at Teen Time (Richard Robinson was there: “The band were wearing those Kingston Trio shirts—short sleeves with the V tails worn outside pants”), the Speakeasy on NW 13th Street, the Hootenanny (later known as Dub’s), and one out-of-town performance Don Felder clearly recalls: “My mom drove us out to Palatka, and we played some Little Women’s dinner at night so we had to stay in a hotel, and she stayed in one room, and me and Stephen and the other two guys stayed in another room. We just piled in.”

Accidental Trio, Gainesville High School, 1963: (left to right) Jeff Williams, Nancy Willingham, Steve Stills.

As Felder’s mother slept through the night, her teenage son and his fellow band members drank from a bottle of Jack Daniels and bounced up and down on the bed until the frame broke, an event Stills recalled a dozen years later when he and Felder met at a Miami recording studio working on separate music projects.

Then one day in January of 1964, Stills left Gainesville. “He was just not there,” Felder recalls. “He just showed up in town, wound up playing with us, and then vanished. Next time I heard him was his voice on ‘For What It’s Worth’ on the radio, and I went, ‘Wait, I know that voice. That sounds like Stills,’ and sure enough, it was Buffalo Springfield.”

John Scarritt describes Stills’s departure from Gainesville: “I gave him a ride to the edge of town, where he hitchhiked to New Orleans. Stephen lived with Jeff [Williams] part time and me part time, and our mothers just loved him.”

With plenty of work for bands that played danceable music, local groups such as the Continentals and others were already plugging in and rocking out. The story of another Gainesville group named the Madhatters is a perfect example of how bands would form and evolve as members came and went, with at least one or more players continuing the band identity.

THE MADHATTERS

Many local bands were comprised of University of Florida students who met in classes, dorms, or fraternities, discovered a mutual interest in music, and decided to pool their talents. The Madhatters were one such Gainesville band that played in and around town in the first few years of the sixties, and one member’s recollections provide an insight regarding where they played and how they were paid. “There were four of us in the Madhatters,” saxophonist Bryan Grigsby recalls. “In September 1961 we played two frats and a local music venue called the Jazz Scene. I think it was a coffeehouse left over from the 1950s, located somewhere on University Ave. We got paid $60–70 a gig that month. I auditioned for that band at a local beer juke called Cason’s Grocery, a combination beer joint and grocery store located on Hawthorne Road. Alachua County was still dry in those days, and all you could get was 3.2 percent beer. In December of ’61 we played at Camp Blanding. There was a World War 2–era hall there that held dances for the locals. We gradually made more, $100–200 a gig. When Gainesville and Alachua County went wet in 1964, off-campus venues opened up as the local bars were allowed to serve stronger stuff, including Tom’s [214 NW 13th St.]—Trader Tom was one of the first to offer topless dancers; the Dungeon, at the corner of University Avenue and 13th Street; the Speakeasy on North 13th Street; the Locker Room, which became the Orleans Club, which became Dub’s Steer Room; the University Inn, which offered fancy dining surroundings and a fancy dance floor. There were also black venues located on NW 5th Avenue, such as Mom’s Kitchen. We used to jam there after hours. There was a juke out Hawthorne Road called Piero’s Blue Eagle and a heavy-duty redneck juke out where Hawthorne Road crosses Cross Creek. It doubled as a fishing camp, and the sheriff’s department rolled to it pretty often. Our band had a couple of other names too: the Uniques, which folded into the Playboys, which became the Big Beats, which became the Rare Breed.”

The story of this naturally evolving musical ensemble continues with the arrival in Gainesville of a young musician whose last name seems too good to be true. Frank Birdsong played guitar for various bands in the mid-fifties in Kissimmee, Florida, before he enrolled at the University of Florida in 1961. “It was weird how the Playboys got started,” he recalls. “I had only been on campus for about three weeks and was living in East Hall men’s dorm. One night I was sitting in my dorm room playing my guitar and had the door to the room open. I started playing and humming a song and then, down the hall, I heard a saxophone start echoing what I was playing. This went on for a while until a crowd started collecting in the hall listening to us. I finally went down the hall to see who was playing and that’s when I met Jerry White, who was to become our sax player. There was also a guy living on the same floor named Lin Thoms, who played the drums. It didn’t take long for us to put together a little combo and start playing around at some of the dorm rec rooms just for fun. We had no name, just a combo. Another dorm resident, Mike Hollifield, could play bass guitar and so we added him to the group.”

Playboys, 1963. Reprinted from the Independent Florida Alligator.

Later in the year Bill Carter enrolled at the university, and with Carter and Birdsong on guitar, a new sax player, and Randy McDaniel on bass (who didn’t own a bass, so the other members chipped in and bought him one), the Playboys were formed, named after Hugh Hefner’s new men’s magazine. The band emulated the playboy image by dressing in black slacks and white shirts topped with an ascot.

A women’s dormitory decided to have a Playboy dance with attendees dressed as Playboy bunnies, and they hired the Playboys to play. Play, boys, play! An article in the college paper ran a photo of the band happily surrounded by Playboy bunnies, and this bit of free promotion brought the group further recognition and higher performance fees, and the Playboys were one of the busiest bands on the university campus in the early sixties.

The Playboys eventually broke up as members graduated college, got married, were drafted, or were fired, and three members were put on academic suspension for flunking because of the inherent conflict of interest between studying and playing clubs until 2 a.m. Two members stayed in town and were joined by saxophonist Bryan Grigsby of the Madhatters, and guitarist Jim Garcia, who previously played with Jimmy Tutten of Jimmy and the Rockets and later with the Big Beats, becoming the house band in a club north of town named the Hootenanny. The Big Beats had also broken up, and the band’s drummer, Paul McArthur, along with Garcia and Grigsby, joined the two remaining members of the now-defunct Playboys, McDaniel and Carter, to form the Rare Breed, who played around town for several years, recorded several singles, acted as a backup group in the studio and on stage for singers, and became the house band at the Orleans, the new name for the night club called the Hootenanny before it was called Dub’s.

This convoluted story is typical of how it worked: bands formed, merged, broke up, fired members, and lost members, with no plan other than a love for performing music. The university brought students together, and some of these students were musicians freshly arrived in a college town that supported live music. Musical friendships were inevitable, and in a college town with thirteen thousand students, it happened over and over again.

Following a massive promotional campaign and plenty of hype from Ed Sullivan, on February 9, 1964, the Beatles performed five songs on the Ed Sullivan Show for seventy-three million viewers. The girls screamed, the guys stared, the critics howled, the parents shook their heads in puzzlement and outrage, and a large number of teenage boys were immediately fascinated with the idea that you could create such a reaction simply by playing music. And the Beatles quickly rose to become the most successful and influential pop music group of all time.

The Beatles’ American television debut was a jarring experience visually and musically. Everything about the group was fresh and different: the hair, the collarless matching suits, the symmetric stage appearance with McCartney’s bass guitar pointing left, Lennon’s guitar pointing right, Harrison in the middle, and drummer Ringo behind and above. The overall look, the music, and their onstage chemistry combined to form a total entertainment package that had never been seen or heard before.

A glance at the Top Ten albums at the time of the Beatles’ arrival provides us with the context of their American debut. In late January of ’64, the best-selling album in the country was The Singing Nun, a record by a Belgian nun whose folk-style song “Dominique,” sung entirely in French, had topped the singles chart the previous month, possibly the strangest song to ever do so. Three albums by the folk trio Peter, Paul, and Mary were in positions 2, 6, and 10. Elvis Presley, now ten years into his career, held two chart positions with the soundtrack for Fun in Acapulco and an album of previous hit singles. Pop vocalist Barbra Streisand and folk icon Joan Baez were also in the Top Ten, which was rounded out by the soundtrack album from the movie West Side Story and a record by Los Indios Tabajaras, a guitar duo from Brazil with the million-selling single “Maria Elena.”

You get the picture? There was no picture; it was more of a slide show, and it was smack in the middle of this disparate collection of musical expression that the Beatles landed.

One result of their appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show remains a singular achievement. Here is a list of the five best-selling pop singles for January 18, 1964:

1. “There—I’ve Said It Again!” |

Bobby Vinton |

2. “Louie, Louie” |

Kingsmen |

3. “Popsicles, Icicles” |

Murmaids |

4. “Forget Him” |

Bobby Rydell |

5. “Surfin’ Bird” |

The Trashmen |

Three months later, on April 4, 1964, the five best-selling pop singles were, in descending order, “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “Twist and Shout,” “She Loves You,” “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” and “Please Please Me.”

The Beatles had taken over the entire Top Five.

HEY, LET’S GO

The impact of the Beatles (1960–1970) on popular music and on popular culture has been well documented, and we can confidently acknowledge that the four lads from Liverpool changed rock music forever. Tom Laughon, a member of folk group the Southgate Singers and later lead singer of the Maundy Quintet, sums it up by way of example: “We all went from The Kingston Trio to being asked, ‘Are you a boy or are you a girl?’”

There are few precise moments that are a tipping point in social history, and the Beatles’ debut national television appearance is one of them. Locally there was a similar example of how the times, they were a changin,’ as illustrated on a page of the May 1, 1964, Florida Alligator college newspaper. Adjacent to an advertisement for Elvis Presley’s fourteenth movie, Kissin’ Cousins, is an ad for Muscle Beach Party, starring former Mouseketeer Annette Funicello and former teen singing idol Frankie Avalon. Accompanying Muscle Beach Party is a British newsreel from December 1963, The Beatles Come to Town.

Elvis Presley, a surf movie with two stars from a previous musical era, and the Fab Four, all on the same page. Pop culture was about to turn a corner.

In August the Beatles released their first full-length movie to commercial and critical success. Following its release, A Hard Day’s Night screened several times daily in Gainesville for months, and the Beatles had now sold eighty million records worldwide.

The transition from folk music to rock bands had begun, and all across America teenagers wanted electric guitars for Christmas. The massive Sears mail-order catalog offered several pages of musical instruments, and these pages became dog-eared and pored over by young future rock and rollers. If you were persistent and your parents finally gave in, there were several local music stores ready to help you out. The wheels of rock and roll were back in motion.