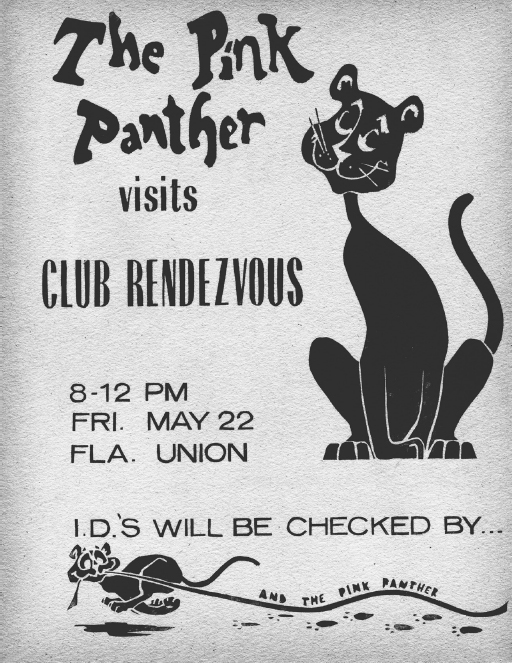

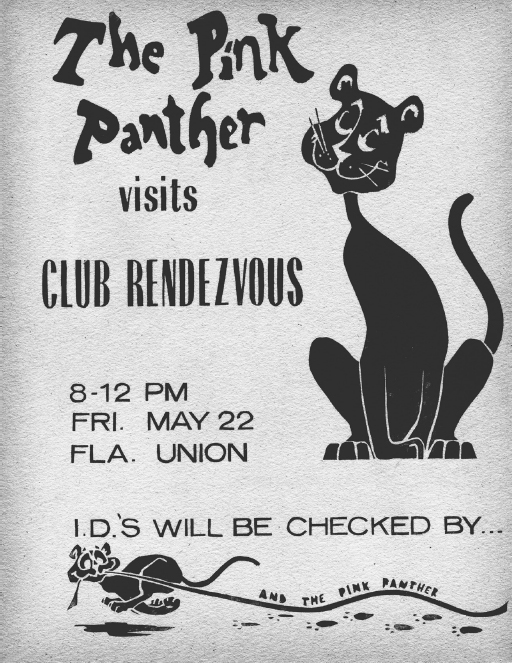

Pink Panthers performance at Club Rendezvous, May 22, 1964. Permission of the University of Florida, Smathers Library Special and Area Studies Collections, University Archives.

LONDON CALLING

1965–1966

“She Loves You” » The Beatles

“Glad All Over” » Dave Clark 5

“My Love” » Petula Clark

“A World without Love”» Peter and Gordon

“Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood” » The Animals

“I Had Too Much to Dream” » The Electric Prunes

“Dirty Water”» The Standells

“Wild Thing”» The Troggs

“Good Thing” » Paul Revere and the Raiders

One spring afternoon in 1964, a fourth-grade teacher at Gainesville’s P. K. Yonge Laboratory School gave in to his students’ pleas and allowed them to put on a classroom concert. The teacher was well aware of a recent trend in popular music that had captivated the interest of his students.

After the class returned from the cafeteria, four members of Frank McGraw’s class put on Beatles wigs (from Jolly’s Toyland) and stood in front of their classmates. Three held brooms as if they were guitars, with a fourth student sitting on a chair behind the trio, a pencil poised in each hand as the drummer. McGraw reached down and placed the needle of the record player on the 45 single of “She Loves You.” As the song began playing, the four students sang along: “She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah,” shaking their heads wildly with each “You know you should be glad / Ooo!” At the song’s final “YEAH!” the Faux Four bowed in unison just as the real Beatles had on the Ed Sullivan Show a few months previously. The audience burst into applause and laughter; the band members removed their wigs and became fourth-graders again. Seemingly in an instant, the Beatles had become part of the American cultural mainstream.

What was going on here? A few months ago few Americans had heard of the band, and now their music was on center stage around the globe. The British had invaded our country, once again, but this time with music and fashions.

LOVE ME DO

A cultural phenomenon known as the British Invasion had begun. Ed Sullivan quickly responded to the unprecedented success of the Beatles’ appearances on the show by rapidly presenting more English pop groups. The next group to appear was a London band named the Dave Clark 5, who performed “Glad All Over,” a song that recently knocked the Beatles “I Want to Hold Your Hand” off the top of the British charts. Other English musical acts soon followed: the Rolling Stones, Freddie and the Dreamers, Gerry and the Pacemakers, the Searchers, Herman’s Hermits, the Animals, Billy J. Kramer with the Dakotas, the Bachelors, Peter and Gordon.

British pop groups had absorbed various aspects of American blues, rhythm and blues, rockabilly, and rock and roll music, added contributions from their own vast musical heritage, and then sent the result to America as a hybrid of both cultures. The songs and lyrics sounded fresh to our American ears, as did the names of the groups: “Groovy Kind of Love” by the Mindbenders; “Doo Wah Diddy Diddy” by Manfred Mann.

British culture was also arriving in America through the cinematic successes of Mary Poppins, My Fair Lady, and secret agent James Bond, starring in his latest movie Goldfinger. British fashion became the rage—miniskirts; Oh! de London perfume; the skinny silhouette of supermodel Twiggy; long bangs, heavy eye shadow, and straight hair on women; the fashions of London’s Carnaby Street; Beatle boots; and English Leather cologne. Within the year Gainesville’s southern culture was inundated with British pop groups on the radio and television and British fashions in magazines and on the clothing racks of department stores. Roger Miller’s 1965 song “England Swings” hit the Top Ten with lyrics extolling all things British: “England swings like a pendulum do / Bobbies on bicycles two by two / Westminster Abbey, the Tower of Big Ben / The rosy-red cheeks of the little children.”

British culture differed enough from American culture to be appealing while not being totally alien; after all, the English spoke English—more or less. In the first few years following the Beatles’ arrival, many Gainesville bands did their best to emulate the British styles in music and dress, with some band members affecting a British accent.

FOLLOW THAT DREAM

Tom Petty was among the many who were transfixed by the Beatles’ performance on the Ed Sullivan Show. As Petty commented in the documentary Runnin’ Down a Dream, “It all became clear. This is what I’m gonna do, and this is how you do it.”

Petty was already hooked on rock and roll, in part through his encounter with Elvis Presley three years earlier. Tommy’s uncle Earl owned and operated Jernigan Motion Picture Service, a business whose services included filming special events, parades, and football games and providing technical support for movies produced in and around central Florida. When Mirisch Productions arrived in July of 1961 to shoot several scenes for Elvis Presley’s upcoming movie Follow That Dream, Earl Jernigan invited his eleven-year-old nephew along to meet Presley and watch the filming.

As Petty recalled, a line of white Cadillacs pulled up to the movie site in Ocala. As car doors opened and the passengers began exiting one by one, Elvis finally stepped out, recalls Petty, “looking like nothing I’d ever seen before.”

After being introduced to Elvis and receiving a brief nod from the King, Tommy watched as Presley was forced to shoot one simple scene over and over, because of the large group of fans who broke through each time the filming began of Elvis driving up to a bank building and stepping out of the car. Petty returned to Gainesville deeply impressed.

Tom’s neighborhood friend Keith Harben had a sister who was an Elvis fan and had just moved out of the house, leaving behind her collection of Elvis Presley 45s. Petty traded his slingshot to Harben for the box of records.

And that was that. “The music just hypnotized me,” he recalls. “The hook was in really deep. I’m in about the fifth grade, and I’m playing 1950s records, and it’s all I want to talk about. Even the other kids thought it was weird. I didn’t have the faintest dream of being a musician—I just loved to listen to it.”

It was the early Presley recordings that got Tommy all shook up, songs such as “Heartbreak Hotel,” “Jailhouse Rock,” “One Night,” “Hound Dog,” and “Don’t Be Cruel,” all golden oldies by the mid-sixties.

What was a young boy to do?

C’MON, LET’S GO

The answer of course was to start a band, an idea made abundantly clear a few years later with the success of the Beatles, four guys singing and playing as a group. This group approach was sort of new as an idea. Most early rock and roll acts were singers—Roy Orbison, Chuck Berry, Elvis, Fats Domino, Little Richard. If there was a band involved, they were usually second-billed to the singer: Bill Haley and His Comets, Gene Vincent and the Blue Caps, Buddy Holly and the Crickets. A self-contained band performing their own songs and playing under a collective name such as the Beatles or the Kinks or the Who was a relative novelty as a musical entity. As Petty recalled, “the minute I saw the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show—and it’s true of thousands of guys—there was the way out. There was the way to do it. You get your friends and you’re a self-contained unit. And you make the music. And it looked like so much fun.”

Tom Petty was only one of many Gainesville teens that watched the Beatles on television that February night in 1964, but the difference was Petty acted almost immediately. “Within twenty-four hours, everything changed. I wanted a group. I set about scouring the neighborhoods for anybody that owned instruments, that could play instruments.” He located a few neighborhood kids with similar interests who gathered at his house, plugged into the one guitar amplifier, chose a song they all knew, and began to play. This sound, he recalled, was the biggest rush of his life. They were making the music.

Thus, in 1964 the Sundowners were born: Dennis Lee, drums; Richie Henson, guitar; Robert Crawford, guitar; and Tom Petty, guitar and vocals. With a repertoire of four songs—“House of the Rising Sun,” “Walk, Don’t Run” by the Ventures, and a couple more—the Sundowners played their first gig at a high school dance. None of the band members was old enough to drive, so Dennis Lee’s mother brought the group and their gear to the school in her station wagon, waited for the end of the show, and drove them home. At later gigs they asked that she drop them off down the street so no one saw that a mom was driving them around. The band rehearsed at Tommy’s house, in a backyard shed covered from floor to ceiling in carpet to deaden the sound—unsuccessfully. “The cops would come daily,” Petty recalls. “From complaints. They were really nice. They’d say, ‘You can play another hour, and then you’re gonna have to knock it off.’ This would go on every day.”

Obsessed is a term mentioned by several of the musicians profiled in this book, including Petty. “We were working guys. We were either practicing or playing all the time. We were obsessed with it. Completely.” The Sundowners practiced constantly and immediately found work every weekend, playing fraternity gigs and high-school dances.

Petty soon switched from guitar to bass, playing a Gibson EB-2 through a Fender Tremolux amp, both bought by his father, Earl, in a rare and genuine show of support. The group wore Beatle boots bought at the local self-service shoe store, and Mrs. Lee sewed band uniforms for each member: pink collarless jackets and ruffled shirts. Worn with tight black trousers, the Sundowners were striving to emulate the look of the first wave of British groups that appeared on television in later months, such as the Dave Clark 5 and the Kinks.

HERE COME THE LEADONS

Faculty members hired by the university occasionally arrived with families that included musicians, and they came from all regions of the country. The Leadon family is one such example. The University of Florida had hired Dr. Bernard Leadon as a professor of aerospace in early 1964, and with his arrival from San Diego, the population of Gainesville increased by eleven—Dr. Leadon, his wife, Ann, and their nine children.

Bernie Leadon was the eldest, born in 1947 in Minneapolis, where his mother played piano and demonstrated sheet music songs at a music store; Leadon recalls her as being a great “stride pianist,” a style that required considerable technical skill. Yet it was country and bluegrass music that fascinated him, especially banjo, admitting he was “obsessed with it, eaten up with it.”

Already musically proficient at the age of seventeen and searching for musical companionship, Bernie Leadon arrived one day at Lipham Music, the main music store in town, and asked for the name of the best local guitarist. The answer was Don Felder. Bernie called the Felder home and was told that Don was on his way home by bus from a gig in Palatka; Leadon drove to the bus depot to await Felder’s arrival.

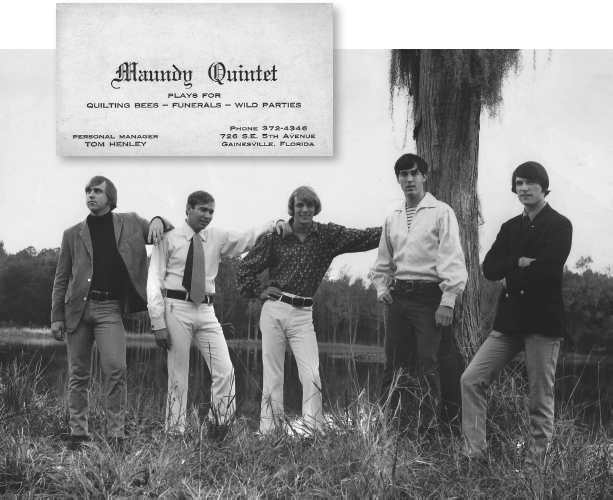

The two players became immediate friends and soon found they were both highly proficient on guitar but in differing styles. Felder played rock and roll electric guitar, and Leadon played country and bluegrass on acoustic guitar and banjo. Each taught the other what he knew, a mutually beneficial situation all around, as Felder recalls: “Bernie and I had two bands; we had the Maundy Quintet or whatever we were doing for a weekend band, and then during the week we had a bluegrass band. Bernie was a phenomenal bluegrass player; taught me how to play bluegrass flat-top and mandolin. We had three guys: Bernie, me, and this really tall guy who worked for the Florida Fish and Game Commission named Dale Crider. He played mandolin. We’d go on Monday or Tuesday night to play these little bluegrass country gigs just for fun. What little I learned about bluegrass I learned from Bernie. That was his primary and deep-rooted musical heritage and background. When we first met, he didn’t even own an electric guitar, so we went down to Lipham’s. He bought a Gretsch Tennessean, and I bought a Martin acoustic and eventually traded it and got another D-35. But we kind of shared our music together.”

Crider recalls Leadon as “the first 5-string banjo player in shorts … barefooted.”

PINK PANTHERS

Another recent Gainesville arrival was a high school sophomore from Bloomington, Indiana, named Sumner Wayne Hough, who practiced drums at ear-splitting volume in his music room, playing along with records of surf bands. “Boomer” Hough soon joined forces with singer Tom Laughon, whose father was pastor of the First Baptist Church, and along with bassist Willis Harrison and guitarist Sol Varron, the Pink Panthers were born, playing dances at the university and at the Woman’s Club for Cotillion and Junior Assembly social functions. The band was named after the stuffed pink panther Boomer had won for his girlfriend at the state fair, and it shared the stage at all of the group’s performances.

The image of a band was an important aspect of a group’s overall appeal, and the current trend in the pop world was matching uniforms, so the sewing skills of yet another Gainesville mother became part of the fabric of local rock and roll history. “My mom made us pink Nehru jackets to look like Beatle jackets,” Laughon recalls, “and we had white turtleneck shirts, and Beatle boots, and we looked like crap. We even wore wigs while we were letting our hair grow out.”

Pink Panthers performance at Club Rendezvous, May 22, 1964. Permission of the University of Florida, Smathers Library Special and Area Studies Collections, University Archives.

Eventually Sol Varron and Willis Harrison left the group, and Bernie Leadon, Don Felder, and bassist Barry Scurran joined Laughon and Hough to continue the Pink Panthers’ gigs. With the Beatles and the British Invasion in full swing, the name Pink Panthers sounded hopelessly out of date, so the band searched for a more English-sounding name. Leadon’s Catholic upbringing brought to mind Maundy Thursday, the day before Good Friday. Maundy did sound British but wasn’t enough for a band name. Tom Laughon began scanning names of currently popular groups, and when he got to the British-sounding Sir Douglas Quintet, he suggested adding the word quintet to Maundy. Ironically, Texan Doug Sahn had chosen the name Sir Douglas Quintet for his group for the same reason: it sounded British. Other American bands that chose British names included the Buckinghams and the Beau Brummels. Being English was suddenly where it was at.

Maundy Quintet, circa 1966: (left to right) Bernie Leadon, Barry Scurran, Don Felder, Tom Laughon, Boomer Hough. Permission of Tom Laughon. Above: Most working bands had business cards.

The Maundy Quintet played the current popular songs and other favorites, focusing on the Top Forty hits that blared from radio speakers across the nation. The band learned songs by the Beatles, the Zombies, Lovin’ Spoonful, Booker T. and the M.G.’s, the Animals—whatever was danceable and on the pop charts or had once been on the charts and was familiar to both band and audience. When the group added local teen whiz-kid David Mason on organ, making them a six-piece band, they kept the Maundy Quintet name, explaining that you got a bonus when you hired the Maundy Quintet—a free sixth member.

With “Maundy Quintet” boldly painted in Old English script on the sides of the band van, parked daily in the Gainesville High School parking lot as Boomer attended classes, the group presented themselves as a possibly English group without actually claiming they were. What was never in doubt was the band’s musical skills.

HAIR TONIGHT, GONE TOMORROW MORNING

In Gainesville in the mid-sixties, it was almost impossible to wear your hair below your ears while still in high school. “That was the craziest part of the Maundy Quintet,” Boomer Hough remembers. “Bernie was at GHS, I was at GHS, but you couldn’t have long hair and go to school, so we wore wigs on stage; we went to May Cohen’s [department store] in Jacksonville and bought some wigs and wore them. And Bernie was trying to grow his hair out long, and he got thrown out of GHS because of his hair, and that made the front page of the Gainesville Sun. Then we started using this stuff on our hair, Dippity-Do. We’d grease our hair back so that we could grow it out long. As long as it didn’t go over your ears, you were allowed to go to high school at GHS. So we would start to grow our hair out to some degree and put this stuff in our hair to keep it so it wouldn’t go over our ears.”

Another musician who owned a wig for the same reasons was Jim Lenahan, who in junior high played drums for the Diplomats, then the Road Runners, followed by the World Shattering Agents and the Certain Amount. Lenahan had been performing since the age of five, singing on local radio shows and on the Glenn Reeves television show in Jacksonville, the same Glenn Reeves who ten years earlier had sung the original demo to “Heartbreak Hotel.” When the Certain Amount disbanded for the summer as two members left town on student break, Lenahan and keyboard player Trantham Whitley wanted to keep playing and hooked up for the summer with the Sundowners, who had a regular gig out at nearby Keystone Heights on the pier. Sundowner Tom Petty had already met Lenahan through a common bond: “I met him in high school, and he had long hair, and he was one of the five or six guys in town with long hair, so you would kind of group together so that you wouldn’t get your ass kicked. Because there was the real danger of rednecks beating the shit out of you.” Petty had somehow convinced the high school administration that his own long hair was a job requirement for playing rock music, and they agreed, although getting harassed by certain students for having long hair continued.

Playing an out-of-town gig was a step up for any band, even if it was just a few miles away in Keystone Heights. Regional bands in Florida played a much wider area of the state, and when they came to Gainesville, local musicians took notice.

Ron and the Starfires was one such band, based in Auburndale, 120 miles to the south. The band played frequently in Gainesville, averaging twenty gigs in town each year during the mid-sixties, mostly at fraternities. Lenahan remembers them as a white soul band playing mostly rhythm and blues, with a set list that included songs by Jimmy Reed, James Brown, Ray Charles, and other black artists, as well as songs by Jerry Lee Lewis and Lonnie Mack, eventually adding songs made popular by the British Invasion. By every account they were an excellent live band. “Petty and I went to see Ron and the Starfires at the Gainesville American Legion Hall in 1965,” Lenahan recalls, “and sat right in front of the stage. We were awestruck at how good they were and kept talking about it all through the set. When they took a break, Tom and I were walking out, and Ron and lead guitarist Carl Chambers stopped us and wanted to kick our asses. They thought we were laughing at them during the set. I assured them that we thought they were the best band we’d ever heard, and we became fast friends after that.”

INTOLERANCE

The presence of the University of Florida was one of several factors that made Gainesville a liberal oasis in a conservative state, but even still, the city population included those who were extremely conservative. With roads from nearby rural towns such as Archer, Newberry, Hawthorne, Waldo, and Williston all converging in Gainesville, there was often quite a mix of people routinely in town, farmers and professors and businessmen, whites and blacks, young and old, the highly educated along with the barely literate. Along with this convergence came variously expressed hostile attitudes toward race, hair length, and fashion choices. Stated more directly: there were some intolerant people in Gainesville and the surrounding areas who expressed their disapproval with physical violence. Redneck was not a term applied to every rural Floridian, just to the violence-prone and actively intolerant among them.

It was hard to tell whom rednecks hated more: African-Americans because of their color, or white males who had long hair. It appeared that the latter drove rednecks the most crazy. Everybody knew that being African-American was not a choice, but growing your hair long was. “Ain’t you a cute girl” was the least of what you’d hear. The routine went roughly like this: you were insulted to your face as a “sissy,” a “girl,” or a “queer,” instant fighting words to a redneck, and when you didn’t respond with an offer to fight, you were perceived as weak or afraid, emboldening them even more. And so it went. One GHS graduate now in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame recalled being grabbed by one of the high school varsity football players and hung upside down by his heels from the second-story school walkway because of his long hair. Based on this action and the relentless threats from other students to “kick his ass after school,” he carried a tear gas pen with him for protection.

This was no joke. In certain areas of Gainesville up through the mid-seventies, you showed up with long hair at your own peril. You were careful where you went around town. This oppressive atmosphere inadvertently created a strong bond among long-haired musicians and encouraged an instant sense of community.

But despite the constant threat of harassment, hair continued to grow, and Gainesville bands continued to form and find employment. Bands were playing all around town at fraternities, bars, college dances, roadside lounges, teen dances, and gym sock hops: the Druids, the Playboys, the 5 of Us, the Birdwatchers, the Casanovas, the Henchmen, the Limits of Persuasion, the Epics, the U.S. Males, the Centurys, and regional acts such as Leesburg’s the Nation Rocking Shadows and Ron and the Starfires.

PLUG ME IN

Bands needed musical equipment to perform: electric guitars, bass guitars, drum sets, an organ or electric piano, and microphones and speaker cabinets and a sound system for vocals. Gainesville’s music stores were only too happy to oblige. The Beatles indirectly helped sell millions of dollars’ worth of musical equipment through inspiring the creation of bands that wanted the same brand and model instruments and amplifiers as those used by the Fab Four.

Lillian’s Music Store (112 SE 1st St.) in the heart of downtown was the oldest music store in Gainesville, a small mom-and-pop business with a genteel clientele of piano teachers and students, stocked with sheet music and a few acoustic guitars, a piano or two, and glass-paneled wooden counters displaying the usual assortment of metronomes, tuning forks, and Marine Band harmonicas. Lillian’s was where you might go to buy a spare guitar string or a graded piano instruction book, but that was about it.

West of downtown at 1226 W. University Avenue was Marvin Kay’s Music Center, a small annex of the main music store in Jacksonville. Nestled in a row of small storefronts that are still there today, Marvin Kay’s sold electric guitars, amplifiers, drums, and related musical gear for the rock musician. Located a few blocks east of 13th Street—the name of US 441 as it ran through the city—Marvin Kay’s was a convenient stop for out-of-town bands, and with the university campus just a block away, the store catered to the nearby student population.

But the place to be, the store where most Gainesville musicians eventually found themselves hanging out, was Lipham Music.

TALK TO BUSTER

Lipham Music eventually became known as the social hub for most every rock and roll musician in Gainesville and midland Florida, a music store located at 1004 N. Main Street, in the south corner of the Gainesville Shopping Center, a business where at various times three current Rock and Roll Hall of Fame members worked behind the counter: Tommy, Don, and Bernie.

Buster Lipham was born in El Paso, Texas. In the early fifties the family moved to Midland, Texas, where his father, T. V. (Theron Velford), worked at Wimple Music. Sent by the store’s owner to a music trade show in Chicago, T. V. met C. Asbury Gridley, a dapper man with a pencil-thin moustache, who dressed like a Hollywood actor and who owned several Gridley’s music stores in the South, including one in Gainesville, Florida. Gridley was looking for someone to manage and eventually purchase the stores. T. V. agreed to manage them, and the Lipham family soon relocated from Texas to Tallahassee, Florida.

Keeping track of five stores in two states kept T. V. Lipham constantly on the road, accompanied by young Buster, but he was soon given an ultimatum by Mrs. Lipham: choose one store or find a new wife. With marriage intact, the Liphams moved to Gainesville in 1954, where Gridley Music (1025 W. University Ave.) prospered; by 1960, he had moved to the larger space in the new Gainesville Shopping Center and after a year or so renamed the store Lipham Music.

As a longtime dealer in the major music brands and with generous floor space for the latest music gear, Lipham Music was perfectly positioned for what happened four years later: a vast demand for musical gear triggered by the bands of the British Invasion and the Beatles’ global success.

“That was a beautiful time,” Buster recalls in 2012, as he glances through photos of the showroom floor from the mid-sixties. “The Beatles made rock and roll happen for everybody. Everybody was going to be a star. We had more garage bands than you could shake a stick at. We sold Farfisa Combo Compact Deluxe organs, Hofner basses, and Rickenbacker guitars like crazy. It was 1967 when Tom Petty was working for us … everybody hung out at the store on Saturdays.”

Buster was a warm, personable, energetic, and shrewd businessman intent on expanding the store to meet the explosive demand for rock and roll musical equipment. Having grown up in Gainesville, Buster was a part of the local community and comfortable in dealing with the wide variety of clientele of different ages, backgrounds, and musical interests who patronized the store. Certain aspects of his approach to business enabled many young players to get their hands on top musical instruments and begin playing in bands and earning money. Lipham was an enabler of rock and roll in the best sense of the word.

It was simpler time with a level of trust unimaginable today. The music store offered credit terms to teenagers, and with a small down payment you could go home with musical gear, and generally speaking, you had a year to pay it off.

The weekly visits to make payments brought you to the store often, and while you were there, you would meet and hear other musicians as they tried out guitars and amps, developing an informal sense of community among players. Drummer Stan Lynch recalls that the weekly payment amount wasn’t specified; you paid what you could, and the amount would be duly noted on a card along with the date of payment.

Lipham Music guitar rack, late sixties. Permission of Buster Lipham.

A teenager walking around Lipham’s was akin to a kid in a candy store, gazing up at the very same brands and models of musical instruments played by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones and the Kinks, hanging on the wall behind the counter by the dozens: new Fender, Rickenbacker, Mosrite, and Gibson electric guitars and Martin acoustic guitars. On a shelf overhead were stacks of drum sets: Ludwig and Gretsch and Rogers and Slingerland. On the showroom floor were rows of amplifiers by Fender, Gibson, Sunn, Standell, and Kustom, a brand whose over-the-top metallic-sparkle tuck-and-roll Naugahyde covering was reminiscent of custom hot-rod upholstery.

The back half of the store was a piano and organ showroom run by T. V., and Buster gradually took over the rock band side of the business as his father concentrated on piano and organ sales, later moving that part of the business across the street in a separate location, opening up even more floor space.

The musical gear came in and soon went out, every guitar amplifier emblazoned with a Lipham Music logo on the grille cloth, a promotional gimmick similar to the license plate frames automobile dealers included on each new car. A band onstage became an advertisement for the music store. Buster took promotion a step further. “I had a deal with bands. I said if you buy your equipment from me, and you have a band van or trailer, I’ll pay to have it lettered with your band name, as long as I can add, ‘Equipped by Lipham’s.’” By Buster’s count he had seventeen bands driving around Florida and the southeast with the store name on the van.

Lipham Music supplied the tools of the trade to a thriving band scene, and although it was undoubtedly a for-profit enterprise, the store provided much more than merchandise and is inseparable from the story of Gainesville’s rock and roll roots. The musicians and the store served one another; players met other players there, heard other players there, and lusted after the same shiny new guitars that hung behind the counter saying, “hold me … try me … buy me!” The store made money. The music scene had a place you could hang out.

IT WON’T BE LONG

The year 1964 was a very good year for the Beatles. With a song at the top of the U.S. record charts when they arrived in February for their television appearances, four short months later the Beatles had every reason to feel fine with the release of their first full-length movie, A Hard Day’s Night, which consisted of following the Beatles around London as they went about the business of being the Beatles, including several staged performances of the band playing songs from the soundtrack album. The movie also introduced a new aspect of the band: they were funny lads, with none of the posh mannerisms of the British upper class, and each member had a distinct personality. The Beatles were the real thing and were charting their own individual path through the pop music marketplace. And they made it look so simple: two guitars, bass, and drums. Sing and play.

With the Beatles showing what was possible, everything was in place for Gainesville teens if they wanted to start or join a band. You decided on the name—which was better, Sound Dimension or the Kensington Squires?—you worked on the band image, learned songs, and, of primal importance, learned to play guitar or bass or drums or how to sing. You learned this by copying the records as closely as possible, or you asked someone who knew how to play the song to show you the chords. And there were so many songs to choose from.

The architecture of the basic rock band—drums, bass, guitar, and vocals—became the musical foundation of countless hit records in the years that followed, and this basic instrument lineup continues to this day. Additional layers of sound were available: 12-string acoustic or electric guitar, saxophone and trumpet, orchestral enhancements (strings), sitars, organs, and pianos and other keyboard instruments added texture and variety, but underneath it all was the foundation of drums and bass and electric guitar. Bob Dylan brought this rock band sound to his “Like a Rolling Stone” in the summer of 1965, alienating his folk audience while scoring a number-two single (just below the Beatles’ “Help”) and attracting a large new audience all at once.

In the two years following the Beatles’ appearance on Ed Sullivan, British music groups and acts were a dominating presence in the airwaves in both radio and television. Along with these British sounds was a quickly evolving American pop music scene with its own rich variety: black Motown acts such as the Supremes, Stevie Wonder, the Four Tops; white pop groups such as the Beach Boys, the Young Rascals, the Four Seasons; psychedelic pop by the Electric Prunes; and the garage-band sounds of the Standells’ “Dirty Water.” A bold new world of sound was coming from home as well as from across the Atlantic.

All during this heady time Gainesville was, as usual, teeming with teenagers and college students who listened to the AM radio and bought singles and albums down at the Record Bar or Top Tunes or at variety stores like G. C. Murphy or Woolworth. You could dance to these songs, and bands who learned them could get work at the fraternities, teen centers, recreation centers, and parties, maybe even at the grand opening of the new Sears in the Gainesville Mall. For musicians there were plenty of places around town you could play. Go ahead—start a band or join one. Bring your dad along to Lipham Music, have him talk to Buster, and maybe you could leave the store with a new set of Ludwig Hollywood drums identical to Ringo Starr’s kit, eventually paid off through the money you earned playing at Westside Recreation Center or at the Place or the Woman’s Club.

There was a lot to like about being in a band. Making money indoors at night was a lot more fun than making money outdoors during the day, delivering papers or mowing lawns, especially in the summer. To the bored and frustrated teenager, there didn’t seem to be a downside to learning to play guitar or drums or bass, forming a band, and then getting paid to play cool songs.

There wasn’t a downside. All around Gainesville and all across the country, rock bands began to form.