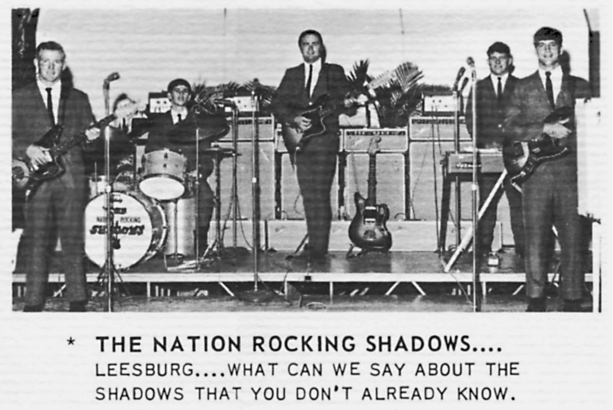

The Nation Rocking Shadows and their wall of Fender equipment.

PEOPLE GOT TO BE FREE

1967–1968

“Light My Fire,” “Hello, I Love You” » The Doors

“Kind of a Drag,” “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy”» The Buckinghams

“For What It’s Worth”» Buffalo Springfield

“Ruby Tuesday”» The Rolling Stones

“Incense and Peppermints” » Strawberry Alarm Clock

“Hello, Goodbye,” “Hey Jude” » The Beatles

“Purple Haze,” “Foxy Lady”» Jimi Hendrix

“2’s Better Than 3,” “I’m Not Alone” » Maundy Quintet

“The Little Black Egg” » The Nightcrawlers

“What a Man”» Linda Lyndell

“Time”» The Tropics

“Get Together”» The Youngbloods

“Born to Be Wild,” “Magic Carpet Ride”» Steppenwolf

“(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay”» Otis Redding

The British Invasion of the American record charts included not only the pop groups mentioned but also solo artists such as Tom Jones (“It’s Not Unusual”), Petula Clark (“Downtown”), Dusty Springfield (“Son of a Preacher Man”), and Lulu (“To Sir, With Love”). The initial influx of music from England, triggered by the success of the Beatles, lasted about two years before the American record charts were again dominated by American acts, including new rock groups with eccentric and sometimes flat-out comical names such as the Box Tops, the Cyrkle, the Left Banke, the Turtles, Count Five, the Electric Prunes, and Strawberry Alarm Clock. It was all a bit zany and a clear indication that what you listened to was different from the music appreciated by your parents. They listened to the Vogues’ “Turn Around, Look at Me,” and you listened to the Human Beinz’ “Nobody But Me,” with its opening lyric of thirty “no’s,” and there was no mistaking one musical style for the other.

Pop and rock music was straying into new territory. The Beatles had been carefully packaged by manager Brian Epstein as a wholesome pop group, singing songs about being in love (“P.S. I Love You”), losing love (“Don’t Bother Me”), giving love (“All My Loving”), and the clearly stated desire to hold hands in “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” Ed Sullivan played it safe through his booking of the Dave Clark 5 (“Glad All Over”), Gerry and the Pacemakers (“Ferry Cross the Mersey”), and the Searchers (“Sugar and Spice”). But then songs expressing a wider range of feelings came along, in the form of the Kinks’ “You Really Got Me,” described by some rock critics as the first “hard rock” song, and the Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” hardly reassuring words for the parents of a teenage girl. The innocence of the Beatles’ “I want to hold your hand” was replaced by the Rolling Stones’ blunt suggestion “Let’s spend the night together,” a lyric that Ed Sullivan requested be changed to “Let’s spend some time together” for the group’s television appearance. Mick Jagger initially refused but finally agreed, on camera rolling his eyes with each chorus. He knew the Rolling Stones’ appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show was instant nationwide exposure, and Ed knew it too. There was no bigger weekly show on television.

With the British Invasion firmly ensconced in the American cultural mainstream, another cultural force was rising up, but this time from within. This force had a lasting effect on music, fashion, and politics: the hippie.

Gainesville was rather cosmopolitan for a small college town, in large part because of the presence of the University of Florida and its large and diverse student body and faculty, and because Gainesville was a pleasant, affordable place to live for those of artistic temperament. True to the adage that birds of a feather flock together, the presence of artistic types attracted those of similar nature, and an arts culture began to develop. Although geographically tucked away in the deepest part of the South, Gainesville was far from being isolated from current cultural trends: the adults, students, and young people of Gainesville read the newspapers, listened to the radio, watched network television, and were as aware as anyone in the country of the new youth movement growing in San Francisco, more specifically in Berkeley.

GET TOGETHER

A Human Be-In gathering at Golden Gate Park on January 14, 1967, was billed as “A Gathering of the Tribes.” Attendees were asked to bring “flowers, feathers, incense, candles, banners, flags.” Twenty thousand people showed up, and speakers included LSD advocate Timothy Leary and the Beat poets Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Gary Snyder. Local San Francisco bands performed, including Jefferson Airplane, Santana, Steve Miller Band, the Grateful Dead, and Quicksilver Messenger Service. An added bonus was the widespread availability of “Owsley Acid,” provided by Owsley Stanley, the first private individual to manufacture vast quantities of LSD and whose product was well known in the Bay area for both purity and consistency. The people gathered and danced, faces were painted, bands played, bubbles and minds were blown, and self-appointed guru Leary advised the stoned crowd to “turn on, tune in, and drop out.”

The Be-In was influential as a prototype for rock music festivals of the sixties, and the event’s large attendance confirmed the existence of a growing hippie counterculture. Gatherings known collectively as the Summer of Love occurred later in the year, when young people on summer vacation descended on the Haight-Ashbury section of San Francisco and other major cities and created a sense of community through their shared antiestablishment views and an evolving fashion sense that brought them together as a separate culture while alienating mainstream society, including the government and most parents. A growing disconnection between the Baby Boomer kids (those born between 1946 and 1964) and their parents had been dubbed the Generation Gap. “Don’t trust anyone over thirty” became a half-serious slogan among young people seeking a different approach to living from that of their parents. One mode of expressing this difference was by embracing the hippie lifestyle. But what was the ethos of this new social being?

The values of your standard-issue hippie were hard to quantify, but there were overarching themes, often summarized in bumper-sticker slogans on the back of a VW bus. A belief in nonviolence (“War Is Not Healthy for Children and Other Living Things”), peace and love (“Make Love, Not War”), freedom of personal expression in speech, dress, and grooming; political and social equality for all races, sexes, and sexual orientations; a rejection of the Cold War mentality of Us versus Them (“One Planet, One People, Please”); organized resistance against the Vietnam War (“Hell No, We Won’t Go”); exploration of communal living from communes to group housing; alternate experiential viewpoints as expressed by writers such as Carlos Castaneda (The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge); alternate architectural concepts such as Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome; living in harmony with nature; experimenting with psychedelic drugs and marijuana; sexual freedom through nontraditional relationships; a rejection of materialism; and a sense of tribalism—to name just a few. To paraphrase the opening song of the 1968 Broadway musical Hair, this was the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, and peace will guide the planets, and love will steer the stars. Many of those who participated in the hippie culture of the sixties were sincere in the belief that the world would soon become a better place if and when everyone realized that love was better than hate, and peace was better than war. Details on how to convince others of these beliefs were sketchy. Although this was naiveté in the extreme, what was wrong with promoting these ideas rather than the opposite?

A subset of the hippie culture was the Jesus Freak, a devoutly religious hippie whose goal was to convince you to confirm Jesus Christ as your personal savior, preferably right now and on the spot. This involved admitting that you were a sinner and that Jesus Christ was the Son of God and died for your sins. Getting someone to agree to these two statements was the Jesus Freak’s mission, and they diligently worked the rock festivals and other counterculture gatherings. It was a tough crowd because most hippies were there to get high and engage in sinful behavior with other like-minded souls. There was serious competition from the Hare Krishna people, who shaved their heads, wore orange robes, and chanted and danced in public, accompanied by finger cymbals. It was a wild, wild West of religious belief.

Gainesville’s relatively liberal atmosphere and a rising student activism helped create a large, very loosely organized hippie community in town, easily identified by their hair, clothing, and lifestyle. For several years a downtown shop called the Roman Sole offered leather goods and custom sandal designs, made by a craftsman who wore sandals and a beard and went by the name of Jesus. No one in Gainesville knew his real name.

Rent and food were cheap, and living arrangements were casual. An area behind Mac’s Waffle Shop at 912 West University Avenue was known as the hippie “ghetto,” and other cheap housing was available just north of campus. Finding a place to live could be as easy as going to the Krispy Kreme doughnut shop and asking if anyone had a place to stay, as Melanie Barr recalls during a 1970 visit: “I walked in with two guys too, yet the first person we asked said we could stay at his apartment. It got a little scary since a few hours after we were there, someone said the cops were outside, and in a panic some green things were flushed down the toilet. It turned out to be a false alarm!”

By 1968 Gainesville was the site of civil rights demonstrations and student-led antiwar protests, and the city had been named “The Berkeley of the South” by University of Florida professor Marshall Jones. Doran Oster, a twenty-one-year-old folk musician who lived in Gainesville at the time, remembers that feeling: “I think everybody back then, or at least people my age, felt like the government was either trying to draft you and get you killed or trying to arrest you for drug use to put you away for many years. And our relationship with the government was very tenuous.”

As the turbulent world of late-sixties political activism began to unfold, rock groups continued as a mainstay of entertainment, and many local and regional bands stayed busy playing all around the Sunshine State and beyond. One of these bands was the Maundy Quintet.

THE MAUNDY QUINTET

The Maundy Quintet is a significant band in the story of Gainesville’s rock and roll roots if only for the fact that guitarists Don Felder and Bernie Leadon eventually became members of the Eagles. But there was more to the band than that. Beyond the overall excellence of the Maundy Quintet’s musicianship and live performance, the band was a self-contained business entity, and a closer look reveals how most aspects of the music business were being covered from within the group.

First, Don Felder and Bernie Leadon were brilliant musicians, and that talent made it easier to get work. Felder was adept at learning songs very quickly, duplicating the original guitar parts on records, and showing up at rehearsals with a song already figured out before the rest of the band had learned it—an invaluable skill for anyone making their living playing in a cover band. Leadon exhibited formidable skill as an instrumentalist and as a songwriter, quickly writing the two tunes the band was to record for their single. Boomer Hough was a drummer well versed in the latest pop styles through listening to the radio and records and playing along on drums. While still a senior at GHS, Boomer was hired as a disc jockey and was on the air from 3 to 4 p.m. daily after school at WUWU, one of the Top Forty AM radio stations in town. He recalls the first record he played was “Somebody to Love” by Jefferson Airplane. Boomer’s simultaneous role as band member and radio personality raised awareness of the Maundy Quintet and increased his status around town, and with this increased standing among teens Boomer was soon promoted to hosting the coveted afternoon drive program. “They moved the station to the new Gainesville Mall,” Boomer recalls, “and that’s where it really took off because the Gainesville Mall was the biggest thing in Gainesville, and [station owner] Leon Mims had put this radio station right in the mall for everybody to walk by and actually watch you broadcast. It was great. I remember interviewing the Beach Boys, Graham Nash of the Hollies, and Buddy Ebsen, who was there to perform at Gator Growl. The crowd around that window in the Gainesville Mall was huge, and it went all the way across the mall to Kinney Shoes. I was the one that got to interview all these people because of the popularity of my afternoon drive shift.” In other words, Boomer was the local star interviewing the national and international stars.

Maundy Quintet bassist Barry Scurran had moved to Gainesville from Miami to attend college, and as social director of his fraternity and eventually president, Scurran was well positioned to book the group at fraternities in town and in Tallahassee, and then throughout the state and in the Atlanta area.

Tom Laughon had begun singing at an early age, first with his family at home and later in talent shows in the family group at church camps, and eventually as a member of local folk music groups Tryon and then the Southgate Singers. “The harmony singing, that was the base mark of the Maundy Quintet,” he recalled. “I don’t know if it was from the church, or that we were in folk groups. Barry could always go up to a high falsetto; I was lead singer but basically in that baritone range; Felder sang lower than me. The band did four-part harmonies. And that’s what set us apart.”

Since the band insisted on excellence in all areas, top quality musical gear was part of the band image, and the Maundy Quintet had seen another band that had the right stuff. “Our equipment went from hodge-podge at first to Fender stuff. We had Fender Showman amps. There was a group called the Nation Rocking Shadows; they were the band that had amazing equipment, and that influenced our guys. They all wanted the best. All I wanted was the best sound system. We each had our own microphone on stage. Even Boomer would sing one or two Ringo songs. We spared no expense. Fender guitars—Don and Bernie both had three guitars each; Don had Gibson Les Pauls. Don was really into jazz riffs. He also liked a lot of hollow body guitars.”

The Nation Rocking Shadows and their wall of Fender equipment.

During the summer of 1968, the band played Ondine’s, a celebrity nightspot in New York City, where bands such as the Doors and Buffalo Springfield had appeared. Playing a New York City club was an eye-opener for this top Florida cover band that was making up to one thousand dollars a night performing songs as close to the original recording as possible. “Before we came to New York, we were doing covers,” Laughon recalls. “We were on the circuit, playing the fraternities in town, and Barry would get us gigs down in Miami at the World, a club with four stages. We’d play with the Byrds, the Turtles, pretty good bands. We were getting some good bucks. But when we went up to play Ondine’s, the bands there weren’t playing what all the bands were playing in Florida. They were doing original stuff, or would do an amazing interpretation of a Beatles song. And that’s when Barry, Bernie, and Don said, ‘Man, we gotta get some original stuff.’ That’s when we came back and really started interpreting songs differently, and when Bernie and Don said we needed to record a single. Bernie wrote ‘2’s Better Than 3’ and ‘I’m Not Alone’ very quickly; it really wasn’t a collaborative thing. He worked with Felder on both of them for a very short time—Don helped him with some of the riffs—and a week later we did the two songs live, and then we went down to H&H Productions in Tampa and recorded them. They came out on a ‘vanity’ label called Paris Tower, so there was no label promotion of the record.”

Felder recalls the sessions and the resultant increase in prestige of a band with their own record: “There was a guy named Jim Mueller, one of the leading local disc jockeys at night, and we would go out there and play live on the radio, and Jim would run a two-track and record it, and then every night that we weren’t there, he’d say, ‘Oh, and here’s the local Gainesville band, the Maundy Quintet’ and play ‘2’s Better Than 3’ over the air, and finally we started getting enough response and action so we said we need to make this into a record, and that’s when we went down to Tampa and literally recorded everything live except the background vocals. I think the lead vocal was live—it may have been an overdub—and we ordered and pressed five hundred copies ourselves. It wasn’t a legitimate record deal with a record company; it was a guy that had a studio and a lathe that could cut master discs for pressing records, and we just paid him a few hundred bucks to make this record for us. And then we sold them at gigs and went around to record stations ourselves and did interviews and got them to play our records, and Boomer was a huge asset for that because he was working at WUWU.”

Having their own record provided a huge boost for the band’s local and regional status as well as their performance fee. “2’s Better Than 3” was the most popular record for several weeks on the Gainesville radio station charts in 1967.

Listening to the two songs today provides the expected wave of nostalgia but also evidence of the high quality of Bernie Leadon’s songwriting and Don Felder’s arranging and guitar skills. The band had a distinct sound with a British undercurrent enhanced by an English-inflected vocal sound and harmony, especially the harmonies on “2’s Better Than 3,” and Leadon’s brief banjo solo on “I’m Not Alone” predates his banjo work on the Eagles’ “Take It Easy” by five years. Both these recordings sound fresh more than forty years later and are an example of what Gainesville cover bands could do when they put their minds to it. There seemed to be a lot of potential lurking in some of these garage bands playing around town.

HELL NO, WE WON’T GO

Meanwhile, the outside world was intruding on this burgeoning rock and roll culture, and it wasn’t all peace and love. For American males eighteen years or older in 1967, the outside world included the likelihood of being drafted into the army and sent to Vietnam. Bernie Leadon was certainly more interested in holding a guitar than a gun. “I had a six-month draft deferment when I was nineteen, and the lady who was the head of the local draft board called up my mom cold, right out of the phone book, and said, ‘Your son is going to be classified 1-A next month, but I happen to know there are vacancies at the Army Reserve Center [National Guard], and if I were you, I’d consider sending him over there.’”

Leadon agreed and signed up. “I left on Valentine’s Day 1967 and went to Ft. Benning, Georgia, for basic training. When I came back, I was ready to leave town to seek [my] fame and fortune.”

Leadon eventually found both. Following his arrival in Gainesville in ’64, several of his friends living in San Diego had moved up to Los Angeles, including Chris Hillman, who was currently playing bass in the Byrds, a popular rock group that had released six singles. Their latest hit was the presciently titled “So You Want to Be a Rock ’n’ Roll Star.” Soon after Leadon’s return from basic training in the late summer of ’67, he received offers from two bands to move to Los Angeles, “bands that had record deals with members that had left, and they were going to make a second record. I decided to join the one on Capitol Records [Hearts and Flowers] because that was the label of the Beatles, the Beach Boys, and the Kingston Trio. The same producer who helped us make our record worked with Linda Ronstadt, so I played on Linda Ronstadt records. Pretty soon I was touring with her, making more money with her than I was with my little band. I changed bands every year the first four years I was out there. I worked with Ronstadt, with Dillard and Clark, and that led to the Flying Burrito Brothers with Chris Hillman, what a lot of people called the first country-rock band.”

POP FESTIVAL

The year 1967 continued to be a year of rapid change in popular culture. In June the Monterey Pop Festival was held in California and thus began the establishment of outdoor pop music festivals that continue to this day. Among the acts that performed onstage at Monterey were Jefferson Airplane, the Who, Janis Joplin, Buffalo Springfield, the Mamas and the Papas, and the Jimi Hendrix Experience, whose leader’s flamboyant stage act and revolutionary guitar playing brought the group instant acclaim.

The songs on Hendrix’s debut album, Are You Experienced, were studied carefully by guitarists around Gainesville, who, in learning them, quickly realized that trying to copy Jimi Hendrix’s guitar solos on “Purple Haze” and “Foxy Lady” was another thing altogether compared to playing three-chord rock songs such as “Mustang Sally” or “Good Lovin’.” How did Hendrix get those sounds? And where did he get those clothes?

One aspect of his sound aside from his virtuoso technique was his use of Marshall guitar amplifiers and effects pedals such as the Arbiter Fuzz-Face and the Uni-Vibe. You could buy all this music gear at Lipham Music. As for clothes, they certainly weren’t available at Stag ’n’ Drag or the Young American shop on University Avenue; you probably had to get them in New York City or London. But that became unnecessary after a local store opened that offered the fashions and lifestyle accessories of the new counterculture. The store was named the Subterranean Circus.

SUBTERRANEAN CIRCUS

In the fall of 1967, Bill Killeen stood in front of a vacant warehouse at 10 SW 7th Street and contemplated his recent decision. Killeen’s arrival in town is the story of a new Gainesville resident with an entrepreneurial spirit who saw opportunity in the thriving youth culture of the city. His timing couldn’t have been better.

Originally from Lawrence, Massachusetts, Killeen was the editor and publisher of the Charlatan, a college humor magazine he had started in the early sixties while a student at Oklahoma State University. After moving to Austin, Texas, he continued publishing, eventually relocating in Tallahassee, another college town. Monthly visits to Gainesville to sell copies of the latest Charlatan on campus led him to solicit local ads. “I realized that Gainesville was the place with the most advertising potential, and it had a bigger and hipper student body than Florida State University, so I moved down here in 1965.” Charlatan eventually became the number-one college humor magazine in the country, published from 1963 to 1967. One issue included a discreet nude photo of his girlfriend, Pamme Brewer, who happened to be a student at the University of Florida at the time, resulting in her suspension as a student and a subsequent controversy that brought national attention to the magazine, the university administration, and Bill Killeen, who was happy to trade verbal barbs with the school administration through his letters to the editor in the Florida Alligator.

With seed money from the recently defunct magazine, Killeen rented the 7th Street location for seventy-five dollars a month. He then flew with friends to New York City to buy stock for the store in Greenwich Village, returning with hundreds of posters, buttons, pins, clothing, smoking accessories, and other hippie boutique items.

The Subterranean Circus was an immediate success, a tribute to Killeen’s awareness of current social trends and the vast untapped market in Gainesville for all things counterculture. If you lived in Gainesville and had an Easy Rider movie poster on your wall, and if you wore bell-bottoms, a peace-sign button, and sandalwood beads, chances are you bought them all at the Sub Circus.

Dozens of posters printed in bright fluorescent ink glowed under ultraviolet lighting on the walls of a back room, creating an unforgettable visual effect for first-time viewers. The front counter offered a wide selection of incense, water pipes, roach clips, more than a dozen brands of rolling papers (from six-cent packs of Zig-Zag Wheat Straw to the premium Rizla rice paper at sixty cents, reserved for the wealthy hippie), and handcrafted leather goods made by local artisan Dick North, who offered items such as leather sandals, carry bags, belts, brass peace signs on leather thongs, and other accessories. A display board on the counter held novelty buttons with various mottoes: “Turn on, Tune in, Drop Out”; “Draft Beer, Not Students”; “Stamp out Reality”; “Ban the Bra.” A magazine rack near the entrance offered the latest underground comic books such as Robert Crumb’s Zap Comix and Gilbert Shelton’s Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, along with alternative periodicals unavailable anywhere else in town, such as Rolling Stone, Crawdaddy, Paul Krassner’s the Realist, and the Village Voice.

In a southern college town where clothing ran more toward the preppy styles at Stag ’n’ Drag and Donegan’s or casual wear from Sears or J. C. Penney, the Sub Circus offered the latest styles available in Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco or New York’s Greenwich Village, including the definitive hippie fashion statement, bell-bottom jeans. “We sold bell-bottoms when no other stores knew they existed,” Killeen says. “One salesman sold fifty pair the first day he worked for us. Then there was Nehru shirts and Cossack shirts. We sold so many we couldn’t stay supplied and eventually hired eighteen women to make them, under Pamme’s direction.”

Killeen bought the adjacent building and opened Silver City for clothing and fashion accessories, featuring a long curved stairway built by Ron Blair, a local musician and a skilled carpenter. The Sub Circus and Silver City became Gainesville’s one-stop destination for hippie accoutrements (and were in business until 1990, when the buildings were razed and the property became a hospital parking lot).

For a small southern town to have such a store in 1967, during the early years of the hippie counterculture, was an example of Gainesville’s acceptance and support of new social trends and newly opened businesses. The Sub Circus was known by most patrons as a “head shop” that sold everything you needed to smoke marijuana except the marijuana. Killeen preferred the term “boutique.” Business boomed.

The soundtrack accompanying this rapidly evolving cultural hubbub was the phenomenal amount of pop music being produced on both sides of the Atlantic. The young musicians of Gainesville were busy doing their part to contribute to this banquet of sound, and the first step in almost every case was playing these songs in a cover band.

RODNEY, TOM, RICKY, DICKIE, AND TOM

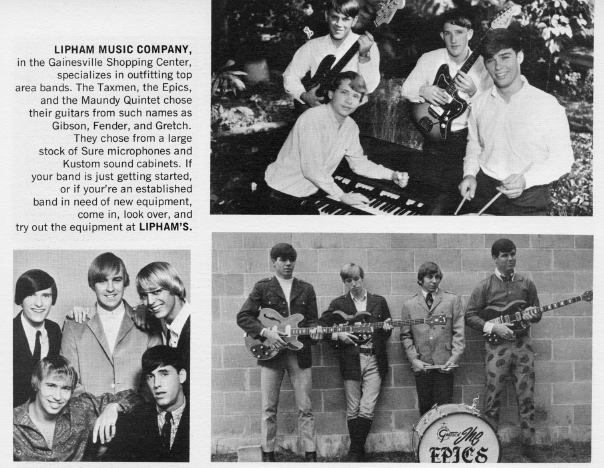

By late 1967 Tom Petty had left the Sundowners and was playing bass as a member of the Epics with drummer Dickie Underwood and the two Rucker brothers, Rodney on vocals and Ricky on rhythm guitar.

Guitarist Tom Leadon, a younger brother of Bernie, joined the band a year after Petty. In Leadon’s words, “Rodney came by with my brother Chris and invited me over to the rehearsal at Petty’s, so I went over there and listened, and they took a break, and I was showing Ricky how to play “Feel a Whole Lot Better,” by the Byrds, that Bernie had showed me. We were sitting outside in the side yard. I was just there listening and showing them a song, but the introduction had been made. The next day I walked back there and knocked on his door, and I remember being a little nervous because I didn’t hardly talk to Petty at the rehearsal, but he came to the door and asked me in, and we just sat and talked, and basically I went over there practically every day after that for about three or four years. We were pretty much inseparable.

“I started hanging around with the Epics and would work the lights for them and after a couple months they asked me to join, and Tom told me later he was pushing for that. He felt he needed a good musician, someone who could really play guitar, and I was only fourteen. The Ruckers were like eighteen, nineteen years old, but I knew more about guitar than they did, and when I joined the band, I was figuring out the records and showing everybody the chords and notes. Why else would they hire a fourteen-year-old player? So that’s how I met Petty.” The Leadon and Petty households were a few blocks apart, so Leadon walked to rehearsals.

The band played extensively around central Florida, driving in a van to gigs and occasionally staying overnight at hotels. The Rucker brothers were older than Tommy and by all accounts were your basic wild-eyed southern boys. “That’s where I kind of grew up, in the Epics, watching these guys,” Petty remembers. “They were nuts, just nuts. Just completely bonko, wild, partying, drunk. They were just crazy. But they had a really good drummer. Dickie Underwood. The guy just played the most solid beat. He could just keep time all day long. He just played great. I loved playing with him.”

The Epics: (left to right) Tom Petty, Rodney Rucker, Dickie Underwood, Ricky Rucker, Tom Leadon.

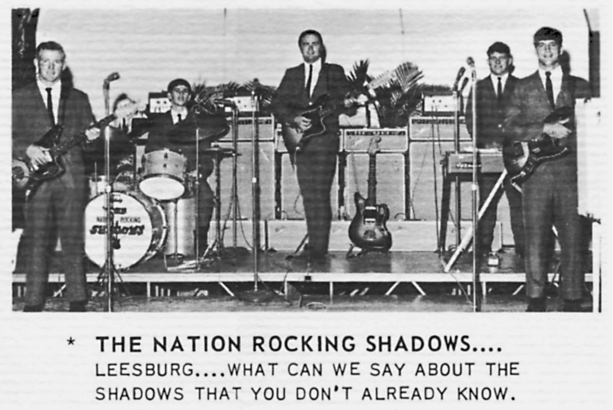

Gainesville High School 1967 yearbook ad for Lipham Music. The Taxmen: David Mason, organ; Jim Forsman, drums; Dean Lowry, guitar; Larry Lipham, bass. The Epics: (left to right) Rodney Rucker, Tom Petty, Dickie Underwood, Ricky Rucker. Maundy Quintet: (clockwise from top) Bernie Leadon, guitar; Don Felder, guitar; Barry Scurran, bass; Tom Laughon, vocals; Boomer Hough, drums.

Jim Lenahan was between bands, as out-of-work musicians often described themselves, when Ricky Rucker asked him to join the Epics as lead singer, although Rucker put it more bluntly. “I was partying with Tom and the guys all the time. At one of these parties Ricky informed me that I had just joined the band, and if I didn’t like it, he would kick my ass. I had no doubt that he could do it too, but I wanted to join anyway. That was how I replaced Rodney as vocalist.”

“Mudcrutch grew out of the Epics,” Lenahan recalls. “Ricky got the idea for the name ‘Mudcrutch,’ and they changed it, keeping the same lineup. Eventually they got pissed off at Rodney for missing too many rehearsals. He was always going off hunting. They finally told him it was either hunting or the band. He said, ‘No problem. Hunting!’ Then Dickie quit the band and joined the army, and Ricky got a job teaching. Suddenly the lineup was Tom Petty, Tom Leadon, and me. We needed a drummer, but we also wanted to play, so we worked up some folk/country tunes and played one drummerless gig at a coffee shop in town called the Bent Card. That country element, which was very much Bernie Leadon’s influence, continued in Mudcrutch after we found [drummer] Randall Marsh and [guitarist] Mike Campbell.”

The Bent Card was sort of a time warp, a coffeehouse modeled after the early sixties folk music venues of Greenwich Village and located in a church building across from the college campus. The decor was Vintage Beatnik, with wooden spools for tables, a bass fiddle leaning against a wall in the corner, a small stage, and a casual atmosphere. The name referred to the warning on an IBM computer punch card not to “fold, spindle, or mutilate.”

The great process of natural selection was clearly in motion. Some members of a band remained members until something more interesting came along—a girlfriend, a job, the chance to shoot a deer—while other members thought of little else besides playing music. A number of Gainesville musicians had already made the commitment to play music, period. There was no plan B for Don Felder, Stephen Stills, Tom Petty, or Bernie Leadon.

ELECTRIC NIGHTS DOWN SOUTH

In 1968 change was in the air, politically, culturally, and musically as the pop music revolution continued with new sounds and new sights. The university presented cultural and musical events funded by various entertainment budgets and open to the public throughout the school year. Up until 1967 the Lyceum Council, staffed by university administrators and faculty with student representatives, chose the musical artists who performed the one or two major concerts per quarter or trimester, with the final decision made by faculty. Most students, however, were not interested in the soft sounds of Mantovani, Al Hirt, Glenn Yarborough, or the Brothers Four, all of whom had appeared in previous years. In the summer of 1967 Student Government Productions took over from the Lyceum Council in choosing and presenting music acts at the University of Florida, eliminating faculty input and control.

This shift in campus government was instrumental in bringing popular rock and pop acts to campus. In 1968, the university presented the Hollies, Ray Charles, Ian and Sylvia, the Fifth Dimension, Dion, the Four Tops, and Peter, Paul, and Mary. A dance billed as a “Freak-Out” at the Reitz Union ballroom featured two local acts, City Steve (a five-piece psychedelic band that included my older brother Jeff on guitar) and Gingerbread, a group with Don Felder on guitar, Chuck Newcomb (formerly of the Jades) on bass and vocals, and drummer Mike Barnett and organist and woodwind player John Winter, two former members of an Ocala band called the Incidentals. Strobe lights and loud live music were combined in an attempt to recreate a psychedelic drug trip, a concert trend that had begun in San Francisco at Fillmore West concerts.

A writer for the Florida Alligator college newspaper was clearly unimpressed as well as unclear as to the names of the two groups: “For those of us who had the fortitude to attend the Men’s Interhall Council dance Saturday night, let me congratulate you for going. Of course, the dance was the worst ‘Freak-Out’ the campus has yet seen. If any real hippies from San Francisco had bothered to show up, the hippie movement might have ended last Saturday night. The main problem was the music. Aside from the fact that ‘City Steve and his Gingerbread Men’ [sic] made vague attempts at making music, they would have done well to play charades.”

While the counterculture was taking root, clearly not all young students endorsed the hippie lifestyle and values. This was still the Deep South, and in a college town with nineteen thousand enrolled students at the University of Florida, not everyone was buying in to the Age of Aquarius.

THE MUSIC GOES ROUND AND ROUND

In 1968 there was plenty of live music in town. Local bands included Styrophoam Soule, the Rare Breed, the Epics, the Brothers Grymm, the Wrong Numbers, Airemont Classic, U.S. Males, and the Centurys. Regional bands such as Tampa’s the Tropics and the Split Ends from St. Petersburg played clubs and fraternities. James Brown brought his soul revue to Citizens Field. John Fred and his Playboy Band, a Louisiana-based group with a chart-topping single, “Judy in Disguise (With Glasses),” the title a spoof on the Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky (With Diamonds),” played at the Place (811 W. Univ. Ave.), a teens-only club that had opened the previous year in the former Rebel Lanes bowling alley. Also playing at the Place was Noah’s Ark, a regional group that included drummer Bobby Caldwell, later with Johnny Winter and Captain Beyond. Ian and Sylvia, the Four Tops, and the Fifth Dimension all played the Florida Gym. The Bent Card coffeehouse presented folk groups the In-Keepers and the Relatively Straight String Band.

The biggest show of the year, however, was on April 10 at Florida Field with the Beach Boys, Strawberry Alarm Clock, and Buffalo Springfield, whose band members included Neil Young and a twenty-three-year-old Stephen Stills, who after hitchhiking out of town four years earlier had returned to Gainesville with his own rock band and performed the Stills-penned Top Ten single “For What It’s Worth.”

It was not much of a homecoming, he recalled in a 2001 interview: “I wore a green Pierre Cardin suit, and a paisley scarf as a tie. I was very much the ‘British pop star.’ Most people didn’t know that I was there, and nobody paid any attention, and there was no review. Nobody cared. It was a Beach Boys show. I think some of my running buds were in Vietnam, and a couple more were off in other colleges, or had moved away. But I was a townie.”

A month later Bernie Leadon arrived in nearby White Springs to perform at the Florida Folk Festival, as noted in the 1968 program: “Bernie Leadon, who was raised in Gainesville, is bringing his group ‘Hearts and Flowers’ all the way from California. The group is made up of Bernie who plays banjo, guitar, mandolin and dobro; Larry Murray, Waycross, Ga., the lead singer and David Dawson, Honolulu, Hawaii, plays Appalachian autoharp. They have two Capitol records out now.”

North-central Florida is far from Southern California, where Stills and Leadon were both living at the time, yet both musicians returned to Florida and performed at large musical events as a normal aspect of their careers, another example of the region’s deep musical culture.

Less than a month after Buffalo Springfield performed at Florida Field, the band broke up, with a farewell live performance at Long Beach Arena on May 5, but in the ensuing years Stills and Young would repeatedly cross musical paths. Bernie’s group Hearts and Flowers also broke up the same year—bands tended to break up—and he soon joined musical forces with Doug Dillard and Gene Clark to record The Fantastic Expedition of Dillard & Clark, with Leadon co-writing six of the nine songs on the album. Meanwhile, Tom Petty was beginning to write songs for his band the Epics, a group that would eventually evolve into Mudcrutch.

NOT SO BLACK AND WHITE

Rock and roll’s roots were nurtured in a varied musical soil that included country music and rhythm and blues. Chuck Berry’s first single, “Maybellene” (originally “Mabellene”), was essentially a rewrite of an old country fiddle tune called “Ida Red.” Berry, who practically invented rock and roll guitar playing, loved country music, as did Ray Charles, whose 1959 hit “What’d I Say” was a hybrid of Latin, rock and roll, and rhythm and blues styles and had a profound effect on the Beatles early in their career, as they performed the song during their months in Hamburg. Midland Florida was a distinctly rural area, and country music was very popular. Even if your tastes ran toward rock or Motown, you could often hear a Buck Owens or George Jones tune wafting from the radio of the pickup truck next to you at a red light. Drop your car off for repair, and the radio behind the service counter might be tuned to WDVH, the local country music station. Bernie Leadon was a bluegrass and country flatpicker fanatic; his bandmate Don Felder listened to blues and jazz guitarists as well as the current pop hit parade. Music, to a musician, was simply music, an inclusive art form. Certain songs could be labeled country, blues, or gospel, but there were as many that were hybrids of all three.

Gainesville had a large black population culturally and geographically separated from whites and in several distinct neighborhoods. The Porter’s Quarters neighborhood was created in 1884 by Dr. Watson Porter, a white Canadian doctor who sold the land exclusively to blacks. With the train depot located nearby, many early residents worked for the railroad and nearby businesses. In the southwest area of town and bordered by Depot Avenue, SW 4th Avenue, South Main Street, and SW 6th Street, Porter’s Quarters was home to many black-owned businesses.

Despite the separation of the races, music brought blacks and whites together, beginning with the discovery by white musicians that they could play with black musicians on the so-called other side of the tracks and, generally speaking, were welcomed.

The majority of this cross-cultural musical collaboration occurred on NW 5th Avenue between 6th Street and 13th Street, another primarily African-American neighborhood. “Where the music was, was around 5th Avenue,” recalls musician Charles Steadham. “It was at Mom’s Kitchen, Sarah’s Place, and Red’s Two-Spot.” Originally named Seminary Avenue, NW 5th Avenue was located in the heart of Gainesville and was the business and social hub of Gainesville’s African-American community.

Mom’s Kitchen, a restaurant at 1008 NW 5th Avenue, offered live music on occasion, and directly across the street from Mom’s Kitchen was a club called Red’s Two-Spot that also presented black musical acts. Charles Steadham recalls playing there at various times with the Georgia Soul Twisters, Lavell Kamma and His 100-Hour Counts, and Weston Prim and Blacklash. A culinary highlight of the neighborhood was Y. T. Parker’s Barbecue at 1214 NW 5th Avenue. Parker served barbecued pork, beef, and goat and was renowned for his dozen or so hot sauces that ranged from mild to Super Saber Jet.

The Allegros: (left to right) Dave Jackson, vocals; Harold Fethe, guitar; Bobby McKnight, Hammond B3; Frank (last name unknown), alto saxophone. Courtesy of Harold Fethe.

Sarah McKnight owned a business variously named through the years Sarah’s Place, Sarah’s Restaurant, and Sarah’s Sandwich Shop at 732 NW 5th Avenue, a trolley-car diner and lunch counter with a wood-frame building attached to one side that served as a nightclub-styled music venue that served beer and presented blues, rhythm and blues, and jazz every Tuesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. Harold Fethe, a white college student, often sat in on guitar with the all-black house band at Sarah’s. The drums and Hammond B3 organ were permanent fixtures, and the house drummer Walter “Fat Papa” Hill was by all accounts a supremely funky player and equally known for his astounding “mouth-trombone” solos. Fethe recalls, “It was a predominantly African-American audience and band, playing soul top-40 repertoire. I learned about Sarah’s from band mates in my fraternity-circuit rock band. Hung out at Sarah’s for a year or so, got invited to play one night, got the job offer, and quit the frat-rock band. Not that we used names much, but I believe Sarah [McKnight] and her husband Bobby called the rear room The Allegro Lounge and the band The Allegros. I played there from ’64 through ’66, blues, R&B, some funky jazz, usually chosen by a series of drop-in singers or the house organist. We played ‘Mercy, Mercy, Mercy,’ ‘Summertime,’ ‘Georgia,’ ‘A Change Is Gonna Come,’ songs with an emotional message or a danceable pulse or both. I remember Lee Dorsey’s ‘Workin’ in a Coal Mine’ and Nat Adderley’s ‘Blue Concept’ were my favorites on the juke box.”

Fethe was one of several white musicians who were drawn to black rhythm and blues and black music in general. Jimmy Tutten was also a white musician who played the 5th Avenue area, as was Linda Rowland, a white singer who while growing up in Gainesville attended both white and black churches.

Rowland eventually began singing in a local band called the Mark IVs that included saxophonist Charles Steadham, a white musician with a similar passion for black music. Linda changed her stage name to Linda Lyndell, Charles Steadham became Charlie Blade, and they both began playing extensively around the South, primarily as the only white members of all-black rhythm and blues acts. Charlie went one step further to virtually reinvent himself as a light-skinned or mixed-race African-American, dyeing his hair and goatee jet black and straightening it in a “process,” wearing sunglasses at all times, and taking on the cultural mannerisms of an African-American saxophone player in a rhythm and blues band. Lyndell so impressed local audiences with her soulful singing that Gainesville businessman and club owner Wayne “Dub” Thomas took an interest in her career and financed some demonstration recordings. The producer of these demo tapes brought Linda to Memphis to record for Stax Records, where she released two singles, the second one, “What a Man,” reaching number fifty in the Billboard rhythm and blues charts.

This unlikely career achievement, being white and having a hit on Stax Records, was marred by racism: Lyndell was an attractive white woman who had embraced African-American culture both professionally and socially. With the attention she got from the press—a white woman who sings with soul—she received death threats from white supremacist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and retired from performing soon after. One listen to “What a Man” makes it obvious that she had the voice to make it as a soul singer. Blade continued his role as a white musician playing in black rhythm and blues acts. By 1969 he had assembled a Gainesville band called the Midnight Playboys, featuring vocalist Weston Prim. The band was renamed Weston Prim and Blacklash and played for years in and around Gainesville at black venues such as the Cunningham’s Country Club and the Village Gate and at the university. “Linda did a television show with us on WUFT-TV,” recalls Steadham, “because we were an integrated band. It evolved from when integrated bands were not in demand to when they were. It was a time of transition. But again, the music was ahead of the general public.” Lyndell and Steadham continued working together, often the only white players in black bands. “Linda and I used to commute from Gainesville to South Florida to play on some weekdays and on weekends. During the week she had to be back at work in Gainesville at eight in the morning, and I had to be in class at UF. We would commute to Ft. Lauderdale to play with this band, Lavell Kamma and the 100-Hour Counts, leave there at three in the morning, and I’d drive ninety miles an hour on the turnpike and get Linda back to work just in time—thankfully there was no traffic at that time of night.”

Soul bands, as black rhythm and blues acts were sometimes called, were very popular at Gainesville’s fraternity parties because you could really dance to the songs. One regional group from Chapel Hill, North Carolina, was a particular favorite in Gainesville and other college towns: Doug Clark and the Hot Nuts. Geared for the college crowd, they specialized in bawdy party tunes just this side of obscene. Singer Doug Clark’s signature tune was “Hot Nuts,” with a chorus that consisted of “Hot nuts, hot nuts / Get ’em from the peanut man. / Hot nuts, hot nuts / Get ’em any way you can,” followed by Clark’s apparently endless supply of risqué couplets along the lines of “See the girl dressed in green? / She goes down like a submarine” or “See that guy from Florida State? / That’s where they teach you to masturbate.” They often dressed outrageously; one New Year’s Eve gig they performed in pink jockstraps and transparent raincoats. At the stroke of midnight, they removed the raincoats. The group played Dub’s and the Rathskeller in Gainesville many times.

Meanwhile, the line between black and white music was being blurred with groups such as Sly and the Family Stone (“Dance to the Music”), Booker T. and the M.G.’s (“Green Onions”), and later with the Allman Brothers Band, all three groups with a mixed-race lineup. Society may have drawn racial boundaries, but apparently music was not willing to cooperate.

You simply could not determine a musician’s color solely through the sound of their musical expression, especially in the South. Anyone listening to Wilson Pickett’s vocals on “Land of 1,000 Dances” would rightfully assume that Wilson Pickett was black—he was—and based on the feel and sound of the music behind his vocals, one would reasonably assume that his exceedingly funky backing band was also black—but they weren’t. Of the nine musicians backing Pickett on the song on May 11, 1966, seven were white boys with an astonishing facility for playing soul music, members of the FAME Recording Studio rhythm section, down in the Muscle Shoals area of Alabama, white guys who played with a black feel. Or was it simply playing with feeling?

It was commonly known among Gainesville bands that to play fraternities, your set list would be enhanced by songs such as Eddie Floyd’s “Knock on Wood,” Pickett’s “Mustang Sally” and “Land of 1000 Dances,” “I Feel Good” by James Brown, and if you really wanted to get down and stay there, “Tighten Up” by Archie Bell and the Drells or “Walking the Dog” by Rufus Thomas, among the dozens of rhythm and blues classics to choose from. There was a strong presence of black music just below the surface in the Gainesville music scene that white players absorbed both directly, by learning songs by black performers, and indirectly just through living in a town in the Deep South with a large African-American population that, while segregated, resided near the center of town rather than in an outer district. Gainesville had soul.

Although white players with a love and a feel for black musical styles were generally welcomed at black musical venues, black musicians could not necessarily show up at white venues expecting a similar level of acceptance. Gene Middleton was a black singer who performed occasionally at Dub’s, backed by the Rare Breed, the (white) house band, whose sax player Bryan Grigsby recalled how “Middleton was allowed to sit with us between sets, but he had to come in the back door.”

There were exceptions. Bobby Griffin, a black musician, played piano at the upscale dining room of the University Inn, a motel that allowed black and interracial dining groups. Owner Nat Pozin, whose social attitudes were not the norm, could not purchase a house in the adjacent Kirkwood neighborhood because it was a “restricted” community—no Jews allowed. Gainesville was a relatively liberal town, but there was still prejudice to spare against Jews, hippies, blacks. You could take your pick.