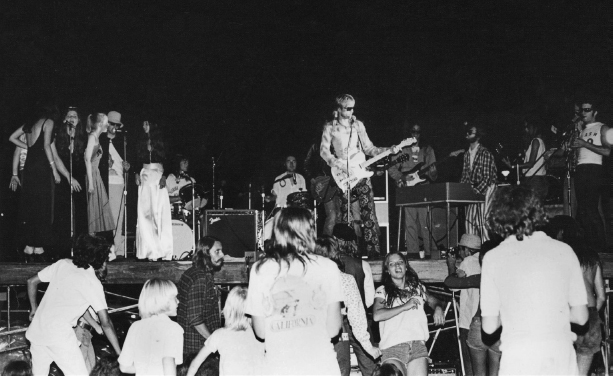

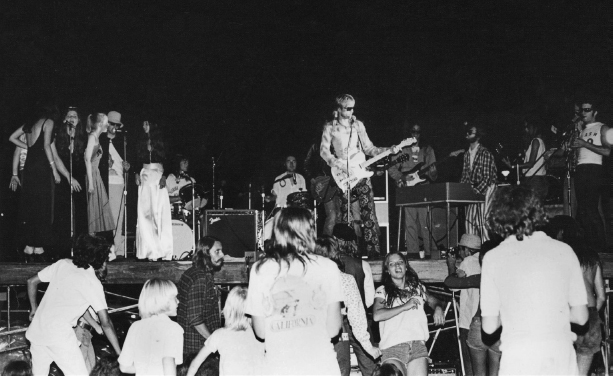

Tommy Ohmage and the Fantabulous Tornados, West Side Park, early 1974. Photograph courtesy of author.

SOMETHING IN THE AIR

1974

“The Joker” » Steve Miller

“Band on the Run”» Paul McCartney and Wings

“Benny and the Jets”» Elton John

“Until You Come Back to Me (That’s What I’m Gonna Do)”» Aretha Franklin

“Takin’ Care of Business” » Bachman-Turner Overdrive

“Radar Love” » Golden Earring

“Hello, It’s Me” » Todd Rundgren

“Hollywood Swinging” » Kool and the Gang

“Spiders and Snakes,” “Wildwood Weed” » Jim Stafford

As the seventies continued to unfold, there was something in the air besides the cloud of marijuana smoke that appeared over so many Gainesville musical events: there were big changes going on in the worlds of politics, culture, and pop music.

Ten years had passed since the Beatles’ 1964 appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show, during which time Americans absorbed the musical influences of England’s “British Invasion” and responded with our own American rock and roll. Now the pop music scene was in a sort of lull as the country struggled with multiple challenges.

GENERAL WACKINESS

Popular music tends to both shape and reflect the culture wherein it lives, and in the mid-seventies the music and culture of the United States of America was in an odd place. The Vietnam War had finally ended, but now there was a new political scandal known as Watergate that led to a Senate committee preparing for impeachment proceedings against President Richard Nixon. In August 1974 Nixon resigned from office, the first U.S. president to do so, replaced by Vice President Gerald Ford, who immediately pardoned Nixon from any possible criminal prosecution.

Even with Nixon gone, all was not well: the stock market was in a slump; inflation was at 11.5 percent; and an OPEC oil embargo resulted in gas rationing, with stations across the country posting a green flag if fuel was available and a red flag if they had run out. The national speed limit was lowered to 55 miles per hour, and “Feelings” by Morris Albert was a worldwide hit, a song whose lyrical and musical content epitomized the worst aspects of seventies soft rock.

Culturally it appeared to be a time of general wackiness as well. South Carolina evangelist Jim Bakker and his wife, Tammy Faye, founded the PTL (Praise the Lord) television ministry, soon to become a multimillion-dollar religious empire. Streaking became a popular fad, with people running naked in public as a sort of pointless prank. Ray Stevens’s latest novelty song was “The Streak,” and it streaked straight to the top of the charts.

THE MUSIC GOES ROUND AND ROUND

Generally speaking these were soft and gentle times for popular music, possibly as an escape from the cultural malaise of the period. The top of the pop singles charts was constantly awash in such sonic lemonade as Roberta Flack’s “Killing Me Softly with His Song,” Paul Anka’s “(You’re) Having My Baby” (voted Worst Song of All Time in a poll conducted in 2006 by CNN.com), John Denver’s “Sunshine on My Shoulders” and “Annie’s Song,” and Terry Jacks’s “Seasons in the Sun,” a record that sold more than fourteen million copies worldwide. On the brighter side of pop music there was the intriguing “Rock On” by David Essex, Bad Company’s hard rocker “Can’t Get Enough,” the supercharged pop of “Waterloo” by Abba, “Band on the Run” by Paul McCartney and Wings, and the Rolling Stones’ “It’s Only Rock and Roll (But I Like It).” Glitter Rock showed its heavily made-up face but arrived more as a fashion statement than a specific music style, where sound and vision merged in such gender-ambiguous artists as David Bowie, Lou Reed, Elton John, Todd Rundgren, Roxy Music, and the New York Dolls, who in full makeup really did look like dolls.

Meanwhile, something else was transpiring on the dance floors of clubs in Miami and New York City, with Kool and the Gang’s rhythm and blues chart topper “Hollywood Swinging” featuring a rhythmic pulse and arrangement that hinted at a musical style soon to come.

The South had plenty of music to offer in 1974. Jacksonville’s Lynyrd Skynyrd, a band you could have heard for fifty cents in the University Auditorium a few years back, had released a second album that included the hit single “Sweet Home Alabama,” a song that rose to number eight on the charts and sold a million. Jim Stafford, a singer/songwriter from Winter Haven, released three Top Twenty singles in a row, “Spiders and Snakes,” “Wildwood Weed,” and “My Girl Bill.” Gram Parsons’s second solo album Grievous Angel was released posthumously and included performances by Emmylou Harris and Bernie Leadon. Parsons grew up in Winter Haven and is considered by many musicians and music critics to be the father of country-rock through his solo work and his role in the Byrds and the Flying Burrito Brothers. The Allman Brothers Band, despite the tragic deaths of founding members Duane Allman and bassist Berry Oakley, were now bigger than ever and had recently performed an outdoor concert along with the Grateful Dead to six hundred thousand people at the Summer Jam at Watkins Glen, New York. In the song “The South’s Gonna Do It,” Charlie Daniels name checks several southern acts, including Lynyrd Skynyrd, Wet Willie, ZZ Top, and the Marshall Tucker Band.

Musically, Florida had a lot going on, and in Gainesville the music venues continued to proliferate. On the university campus were at least eight sites that presented live music, including Florida Field, the Florida Gym, University Auditorium, Rathskeller, and various outdoor venues, such as the Museum and Arts Building, the Plaza of the Americas, Graham Pond, and the north lawn, south terrace, and Grand Ballroom of the Reitz Student Union.

If you lived on campus or just off campus in the student ghetto north of the school, at various times a few minutes’ walk south could take you to the University Auditorium to hear Todd Rundgren’s band Utopia, and a few blocks north you could hear Freddie King at the Longbranch Saloon, either show for three dollars and fifty cents. Down at the Rathskeller you could catch a set by Dion, a rock and roll singer whose career hits included “A Teenager in Love,” “Runaround Sue,” “Ruby,” and “Abraham, Martin, and John.” Venturing south of town to a supper club named the Beef and Bottle, you could catch a new comedian named Steve Martin, who told jokes in a white suit while playing banjo with a toy arrow apparently stuck through his head.

Housing was still inexpensive, and there was an abundance of rental houses where bands lived and rehearsed. The communal living culture was alive and well, and six people in a house could live inexpensively. Road Turkey rehearsed in a house on the east side, next to the Coca-Cola bottling plant; Celebration lived and rehearsed in a house near the Sin City section of town at 16th Avenue and 13th Street. Four blocks north, where a railroad bridge crossed 13th Street, was a five-acre wooded property known as the Stone Castle. David “Lefty” Wright, drummer for the Druids and Brothers Grymm and the Better Half, lived in the house built of stone there, and tenants of another house, nearer to the street, included for a time Tom Petty and the band Cowboy. Mudcrutch would set up outside and play, quickly attracting an audience from passing traffic, and Cowboy played a similar concert there with similar results. The property is now the site of Wildflower Apartments.

There were more live music venues than ever in the town. Regional bands that played included Eric Quincy Tate, Atlanta Rhythm Section, Hydra, Goose Creek Symphony, Cowboy, and Boot, formerly the Split Ends, a popular band from Port Richey, with Bruce Knox on lead guitar, and a drummer who, during his inevitable solo, played drumsticks with built-in microphones plugged into a tape-delay device, resulting in a cavalcade of sound. It was real gone, and Gainesville was alive with the sounds of music.

HEY, LET’S GO

But no matter how hip Gainesville was, a small town is a small town. Having played every venue in the region available to an unsigned musical act, Mudcrutch had now reached a turning point. Petty has said of Mudcrutch, “The whole point of the band had been to make a record.” With the release of their single “Up in Mississippi,” the band had indeed made a record and received regional airplay and a higher performance fee, but that was about it. Mudcrutch’s demo tapes were now making the rounds of the record labels in Los Angeles, or so the band thought. Most likely the tapes were in a large pile in the mailroom along with those of numerous other bands all seeking the same thing, a record contract with a major record label. Unsolicited tapes were generally ignored at major record companies.

The band decided to take matters into their own hands by going to Los Angeles and delivering the tapes in person. In late 1973 Tom Petty, guitarist Danny Roberts, and the band’s stage manager, Keith McAllister, headed west on I-10 in Roberts’s 1969 VW camper van. Soon after arriving in Los Angeles, the three began making the rounds of record companies.

The first stop was Playboy Records, where an executive of the label took them into his office and explained, “Hey guys, it’s not done this way; you just don’t walk in.” Petty recounted his reply: “‘Well, we’re here, and there’s a tape deck, so why not put it on and listen?’ He played not quite thirty seconds, then stopped the tape and said, ‘I’ve heard enough; get out of my office.’” Thus ended the first day.

The next day they dropped in at Capitol Records, whose staff member liked the tape and offered to record a demo of the band; Petty pointed out that Mudcrutch had already made a demo, and the guy had just heard it. However, this was a step in the right direction, and they moved on.

Next stop was MGM Records, whose representative listened to the tape and was more encouraging, immediately offering the band a singles deal, agreeing to record and release one song, and if it did well, then discuss the next step. “No,” Petty countered, “we’re looking for an album deal.” Still, the band had now received an offer from a major label to record and release a single.

Their final stop was London Records, the label the Rolling Stones were on in America. The label representative listened to the entire tape, Petty recounts, “and he starts clapping his hands and jumping around going, ‘This is fantastic. You’ve got a deal! I want to hear the band right away. I want to make a record. This is great!’” When Petty explained that the band was in Gainesville, Florida, the response was, “Well, go get them!”

So just like that, Mudcrutch was offered a record deal with a major label, all on the basis of a live recording of the band. Of course, every bar and concert gig the band had played, every personnel lineup Mudcrutch had been through, and every song the band had played, written, thrown away, or rewritten had brought them to this point. They were ready to make an album. On London Records.

THIS MAGIC MOMENT

The trio drove back to Gainesville, where band, wives, girlfriends, crew, and dogs prepared for the move to Los Angeles. But there was one final detail to attend to. “I do remember having to talk to Ben’s father, who was a big-time judge and was intimidating,” Petty recalled. “And I had to talk him into letting his son quit college. And I made a pretty good case.” Petty’s talking points must have been compelling, as Judge Tench agreed.

During a band rehearsal, the phone rang. Not recognizing the voice, Petty figured it was someone calling about a car they were selling in order to raise money for the trip. As he began describing the car—“Well, it’s not that good, but it’s only a hundred bucks”—the voice at the other end said, “No, no, this is Denny Cordell, and I’m calling for Mudcrutch.”

Tommy Ohmage and the Fantabulous Tornados, West Side Park, early 1974. Photograph courtesy of author.

Denny Cordell was a legendary figure in the music business who as a record producer in the sixties was responsible for hit singles by Procol Harum (“Whiter Shade of Pale”), the Moody Blues (“Go Now”), and in later years for albums by Joe Cocker. Cordell was also co-owner with Leon Russell of Shelter Records, a record company with offices in Los Angeles and Tulsa. Cordell had heard Mudcrutch’s demo tape and told Petty it was the best thing he’d heard in years and suggested the band drop by Tulsa on the way to Los Angeles to meet and check out Shelter’s recording facilities.

Cordell was hoping to convince them that Shelter Records was a better choice than London Records, or as he later described it, “head ’em off at the pass.” The band agreed to visit on their way to Los Angeles and set about raising money for the trip with several local farewell concerts.

One such concert, held outdoors at Westside Park, was a one-shot musical extravaganza billed as Tommy Ohmage and the Fantabulous Tornados, with a lineup that included all the members of Mudcrutch and Road Turkey with additional musicians and backup singers. Tommy Ohmage was delivered to the stage in a Lincoln Continental, dressed tastelessly in clashing paisley clothing and an Elvis tank top. The band played an assortment of rock and roll and rhythm and blues oldies. The audience seemed to like it, and they danced.

On April Fool’s Day 1974 Mudcrutch began the trek west. After a series of automotive mishaps, the band arrived in Tulsa, and as Mudcrutch guitarist Danny Roberts recalls, “Denny Cordell took us to breakfast and told us he wanted to sign us on April 6th, 1974, after we had spent about forty-eight hours in the Church [recording] Studio.”

With an advance of five thousand dollars cash from Cordell, the band arrived in L.A., rented two houses, and began recording at the Shelter studio at the record company’s office, a two-story house off Sunset Boulevard.

It had taken just ten years and a few months for Petty to make the journey from watching the Beatles on TV to begin working on an album with his own band on a major record label.

HIPPIE ATTORNEY

There was something about Gainesville that stimulated the creative thinking of certain new arrivals. One such arrival was Jeffrey Meldon, who gradually became an active part of Gainesville’s growing music community. In the early seventies, Jeffrey Meldon was one of several liberal activists who collectively called themselves the Candle People and whose interaction with Gainesville’s music scene stemmed from their desire to contribute to the local counterculture through community involvement and organization.

Or something along those lines, as idealism ran high in those days.

They needed to start somewhere, as Meldon explains: “On the other side of Lincoln High School, there was a riding stable with about two hundred acres of woods and a rundown cabin; we rented it and called it the Candle Farm. We’d buy giant blocks of wax from the Gulf Oil Company, buy crayons at Toyland, and we’d make hippie candles, over a fire. Then we’d go to the college campus and sit outside the girls’ dorms and flirt with the girls, put our candles on a picnic blanket, and sell them.”

The group formed the Hogtown Food Co-op and an alternative school called the Windsor Learning Community. Then Meldon and company began getting involved with musicians and bands.

Jeffrey Meldon’s interest in music began at a young age through spending time in his father and uncle’s jazz club: “My father and his brother went into the jazz nightclub business in 1950 and opened a club in downtown Cleveland called the Loop Lounge, the largest jazz club between New York and Chicago at the time. It could seat about four hundred people and was one of the top jazz clubs in the country.

“That was my first exposure to music; every significant player in jazz played at this club. Charlie Parker played there for a week in 1954. My dad thought he was the hottest.” At Ohio State Meldon became social director of his fraternity and hired bands for parties, including Booker T. and the M.G.’s and Doug Clark and the Hot Nuts.

In addition to working with Rose Community in helping produce the Mudcrutch Farm festivals, Meldon had recently passed the Florida bar exams and was now practicing law. If you were busted for marijuana possession, Meldon was the attorney to call, the Hippie Lawyer. “I got my law license in November of 1971; at that point Mudcrutch was still trying to get dates, play places, so I started working with Mudcrutch in my law office. They’d come in every week or so, and we’d talk about where they could play. I got them a gig at the Holiday Inn in Lake City, Florida, which they hated because they had to play cover songs, and that’s the last thing they wanted to do. I was their booking agent for some gigs, and I was a lawyer, so they came to me for some advice. They had a young guy, Keith, who was their roadie, but Tom Petty and Tom Leadon were the guys that talked to me. So I went down to Miami to meet with Albert Teabagy; at the time he was working with a big Florida promoter. I went with some Mudcrutch tapes to try to get them some gigs. I almost had them on, but the agencies booking the lead acts always wanted their own acts to open for the headliners; they nixed the deal. So we worked together for a few more months, but my law practice was building, and Petty didn’t want to play Top Forty. I knew they were going to have to go somewhere else to make it big.”

ROTARY RECONNECTION

A year later, Meldon’s childhood friend Dick Rudolph relocated to Gainesville along with his pregnant wife, Minnie Riperton, a vocalist with a five-octave range who had sung in town years ago as a member of Rotary Connection and who would eventually become well known for a song she cowrote with her husband in Gainesville.

“‘Lovin’ You’ was written (or at least inspired by the birth of Maya Rudolph) at Pirate’s Cove restaurant on Biven Arm’s Lake,” Meldon recalls. “I was having dinner out there with Dick, Minnie, and an old ‘Gator’ working for Epic Records, Larry Ellis. Minnie had written ‘Lovin’ You,’ and it was the start of her getting signed with Epic. My wife and Minnie and Dick were all interested in developing music in Gainesville and started trying to create a venue. There was an old barn in the black neighborhood that once was a juke joint called the Cotton Club, a major black music venue in the forties or fifties, but it needed too much work, so we passed. Just around then they got a call from L.A. and a contract and moved there in ’73 and made a record with Epic Records.”

Minnie Riperton’s “Lovin’ You” topped the U.S. singles chart in 1975, reached number two in the United Kingdom, and sold millions. This was the second song conceived in Gainesville that went to number one, the other being 1955’s “Heartbreak Hotel.”

IT’S SO EASY

In pursuing his desire to open a music venue, Meldon eventually settled on the Florida Theater at 233 W. University Avenue, a vacant twenties-era two-story brick building near the center of town with seating for more than a thousand. With his interest in music and a natural talent for the world of business and local politics, Meldon saw in the vacant building the same thing Bill Killeen had seen eight years ago in a vacant warehouse two blocks to the west: opportunity. “Around the end of 1973, the Jacksonville owners were interested in leasing the property. Across the street from it was a clothing store called the Young American Shop. The owner, Jim Forsman, had heard about my interest in starting a music forum, so he proposed that we go fifty-fifty on the project, and we cut a deal to do it. We went to Citizens Bank and somehow got a loan for fifty thousand dollars to renovate the theater. We needed to serve alcohol to make money, so we went to Jack McGriff [owner of the Gator Sport Shop], who was very influential in Tallahassee. He somehow got us a liquor license for the music hall for free. So we had the license.”

Locate a suitable building, find a partner, arrange a fifty-thousand-dollar bank loan, score a free liquor license, and turn a movie theater into an eight-hundred-seat concert venue. Done. There were benefits to starting a business in a small southern town if you knew how.

But how do you convince national acts to play a small college town in north-central Florida? Meldon approached various booking agencies and explained the benefits of playing the Great Southern Music Hall. “I got the names of all the agencies, CMA, William Morris, and started calling them up and said, ‘We have a place that holds eight hundred people; we can do two shows a night, Friday and Saturday, but if it’s a hot act, we’ll do it any other night.’ We wanted to get the acts at a good price; we would take them when they were between shows in Miami or Orlando or Tampa or Jacksonville and traveling to a weekend booking, and we’d take them on a Sunday or a Thursday or whatever. We could get them for a lot less if we could get them on an open day of their tour; that’s how we got our acts.”

Opening night, April 6, 1974, featured the Earl Scruggs Revue. The venue had excellent sound and was within easy walking distance if you lived near downtown. “Eventually we began to expand. There was a wine bar underneath the raked seating near the back—we had a solo artist there—and above on University Avenue we opened the Downtown Deli, a full delicatessen from lunch till after dinner. On the left side we opened the Backstage Bar; it held about a hundred people. The bar would have bands playing during the week. The Backstage Bar was our idea of having live music during the week.”

The Great Southern Music Hall presented fifteen shows in their first year and became a significant concert venue, presenting the top performers of the day in the heart of a small college town. And who played there? Pull up a chair. Meldon consults his list. “Bo Diddley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Patti LaBelle, Jean Luc Ponty, Dave Brubeck, Pat Travers, Jimmy Buffett, Cowboy, Wet Willie, Molly Hatchett, Rossington Collins Band, Leo Kottke, Dan Fogelberg, Richie Havens, Jesse Colin Young, Bob Seger, Steppenwolf, Mahogany Rush, the Outlaws.

“Country Joe and the Fish, Alvin Lee, Savoy Brown, Rick Derringer, Bonnie Raitt, Doug Kershaw, Vassar Clements, Stanley Clarke, Todd Rundgren, Randy Newman, John Prine, Gamble Rogers, It’s a Beautiful Day, Jerry Jeff Walker, Muddy Waters, Jimmy Spheeris, Cheech and Chong, Elvin Bishop, Kraftwerk, Waylon Jennings, Al Kooper, Seals and Crofts, Melissa Manchester, Ray Charles—for two nights … Ray liked his champagne!—B. B. King, Steve Martin, Count Basie, Roger McGuinn, Howlin’ Wolf.

“Grover Washington, Jimmy Cliff, Peter Tosh, Hot Tuna, Quicksilver Messenger Service, the Chambers Brothers, Martin Mull, Poco, Robin Trower, the Runaways, Joan Jett, Spirit, Taj Mahal, Iron Butterfly, Blue Oyster Cult, Souther-Hillman-Furay, the Band, José Feliciano, Tim Weisberg, Leon Redbone, Sea Level, Pat Metheny, John Hartford, Billy Cobham, George Duke, Dave Bromberg, John Hammond, Johnny Winter, Al Jarreau, Gregg Allman, Head East, Johnny Shines, Herbie Mann, Chick Corea’s Return to Forever (with Stanley Clarke), Weather Report, Minnie Riperton, America, and Eric Burdon.”

Not included in this list are the many local bands that opened for these artists and those playing in the two smaller performance areas.

Unlikely scenes transpired on occasion, as recalled by local player Roger Schliefstein: “I met Frank Zappa at the Backstage Bar. I was jamming on harp with some guys in the Wine Cellar, and he was chain smoking and drinking water with his bodyguard, Baldheaded John. I asked Frank if he’d like to sit in with us in the Wine Cellar. He said, ‘Sure, why not?’ I hustled frantically back to the wine cellar to find the band, and we all agreed. I went back to the bar just in time to see some drunk UF student say, ‘Fuck you, Frank Zappa!’ and he poured a mug of beer all over Frank’s beautiful white suit. Baldheaded John picked up this little S.O.B. and literally threw him so hard through the front double doors that the kid landed clear into the right lane of University Ave. Needless to say Frank and John left the bar, and we never jammed. Frank was still trying to keep his beer-soaked cigarette alive.”

SONG OF THE SOUTH

Gainesville bands with the desire and connections to play gigs beyond the local club circuit, and whose members were not blessed with a steady job, could find bookings throughout the Southeast. Along with the long hours spent driving and playing four sets a night were moments of high adventure. Dave Grohl (Nirvana, Foo Fighters) describes this feeling when he explains, “When you’re young, you’re not afraid of what comes next. You’re excited by it.” Gregg Allman also recalls being young and having “so much want-to.” This was also the case for the Gainesville musicians who ventured beyond the city limits in search of other places to play. All roads led out of Gainesville, and US 441 and I-75 beckoned.

Bands booked out-of-town gigs in a variety of ways: through contacts such as friends from high school now in college on the entertainment board of the school or fraternity; through regional booking agencies such as the Armstrong Agency, Bee Jay, Prestige, and Blade Productions; and just as often by word-of-mouth from other bands regarding clubs or bookers. This loose collective of bars, clubs, fraternities, and other music venues spread as far north and south as you were willing to drive—north to Jacksonville, Tallahassee, Atlanta, Macon, Athens, Tuscaloosa; south to Ocala, Orlando, Tampa, and even sometimes as far south as Miami. Tracing the path of Road Turkey—now a four-piece band with Stan Lynch, Carl Patti, Steve Soar, and me—offers an example of mid-seventies band touring.

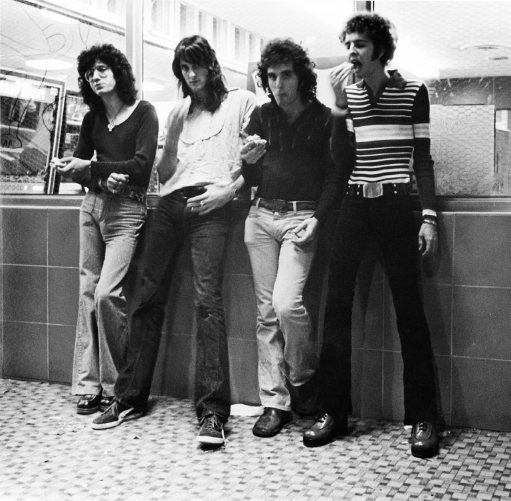

Road Turkey in front of the College Inn, 1974: (left to right) Carl Patti, Stan Lynch, Marty Jourard, Steve Soar. Photograph by author.

In February 1974 Road Turkey played an outdoor show at the university’s North Union Lawn. The next month the band spent eleven days in Cocoa Beach, first at the Pillow Talk Lounge in the Satellite Motel, an aging relic from the fifties, playing from 9 p.m. to 1 a.m. the first few nights and 9 p.m. to 3:30 a.m. the next three. The following week the band found a better gig down the road at George’s Steaks, a club that presented two bands nightly from 9 p.m. to 7 a.m. The Flaming Danger Brothers performed the first shift on Monday but were fired, so Road Turkey played from 9 p.m. to 1 a.m. for four nights, until New Days Ahead headlined Friday and Saturday, shifting Road Turkey to the 2 a.m. to 7 a.m. slot. Customers of this beach bar during the graveyard shift in the mid-seventies included insomniacs, transvestites, drug dealers, prostitutes, night-shift workers not ready to go home yet, and other people of the night.

In June the band played on the North Union Lawn, in August a three-day gig at Our Place, a jock bar in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Neither band, nor patrons, nor bar owner were happy about the booking. Whatever they wanted, it wasn’t us. Venturing from Gainesville to other southern towns was an eye-opening experience. Not every town had a large hippie population; long hair was uncommon; and the eclectic nature of a Gainesville band’s set list was not always welcomed with open ears. “Do y’all play any songs we’ve heard before?” was one of the more polite comments.

By September Road Turkey hit the road, five in a van, towing a U-Haul trailer rented from Tubby’s ’66 service station “for two days,” kept for weeks, and returned late at night. No one at the gas station seemed to notice or care.

The band was booked by the Armstrong Agency out of Macon, Georgia, for four nights at Uncle Sam’s, a large club with two stages just outside the city, built and owned by Capricorn Records president Phil Walden as a sort of personal hangout and concert facility for acts on his record label. Road Turkey alternated sets with Eric Quincy Tate on separate stages, and the band stayed at the Courtesy Court across the highway for ten dollars a night.

While setting up gear the first night playing the club, we noticed a Triumph “chopper” motorcycle parked inside the club’s liquor stockroom, heavily chromed and customized, with Maltese Cross rearview mirrors and extended front forks. The motorcycle was Gregg’s, the bartender explained, but they wouldn’t let Gregg drive home the previous night. Taking the prudent course, a policeman drove Allman home personally in his police cruiser. The bartender put it this way: “We don’t want fifteen million down the drain.” In Macon they looked out for their own.

A visit to Macon’s H&H Restaurant revealed the reverence in which the Allman Brothers Band was held in the town, with the walls of the soul food restaurant adorned with photographs of the band in earlier years, and a painting of Duane Allman playing guitar in heaven, complete with angel wings and a halo, sitting on a cloud. At the H&H, for two dollars and five cents you could eat fried chicken with butterbeans, collard greens, and macaroni and cheese, washed down with a Mason jar of iced tea and finished off with a slice of sweet potato pie.

From Macon the band drove to Atlanta and stayed at a friend’s house, as potential gigs fell through, finally playing one night at Alex Cooley’s Electric Ballroom for one hundred dollars, opening for Mother’s Finest.

In October the band played four nights at the Whippin’ Post in Tampa and were rehired for New Year’s Eve weekend for one hundred and fifty dollars a night. Later in the month Gerry Greenhouse filled in for ailing drummer Stan Lynch, and the band played an apartment complex in Atlanta for one hundred and seventy dollars and an abortive series of nights in Athens, Georgia, at the Hedges, where local favorites Dixie Grease were asked to play alternate sets using our equipment after the owner decided he just didn’t like Road Turkey. That he was describing our booking agent as “that hook-nose Jew in Atlanta” directly to two Jews in the band made it a bit more amusing.

Venturing outside the bubble of “hippie city” Gainesville into the mainstream Deep South was often a reality check for bands that wrongfully assumed the easygoing atmosphere of their hometown was shared by other cities. Generally speaking, it wasn’t.

Thanksgiving weekend back in Gainesville, the band played the Granfalloon, a music club previously the King’s Food Host restaurant, then back to Atlanta later in the year at Hot ’Lana, playing alternate sets with Mazer. A party for the Vero Beach Fireman’s Association in central Florida was followed by one final run in Tampa at the Whippin’ Post for New Year’s Eve week, with Benmont Tench driving down to hang out and jam. Musicians did that sort of thing.

At this level, working bands very much toured on the cheap, sometimes sleeping four or five to a motel room or just as often on someone’s living-room floor in a sleeping bag. But you were young and playing music and getting paid and occasionally laid and seeing more of the great big world beyond your hometown. And adventure or near-disaster lay just beyond the next rise in the road.

LAUGH, LAUGH

The Gainesville band scene had its own unique sense of humor. How else to explain band names such as Mudcrutch? Road Turkey? Fat Chance? Tight Shoes? Froggy and the Magic Twangers? Or the Master Gators, a hastily assembled group of musicians that played a Gators’ basketball game halftime show and received a big laugh when their name was announced over the loudspeaker. Band names such as Mr. Poundit and the Master Race, RGF, Fresh Meat, Flash and the Cosmic Blades, Uncle Funnel, Good Things to Eat, and Mr. Moose seemed to indicate a certain playfulness because, despite inevitable conflicts between band members, and between bands and club owners, despite the inevitable drunken cries of bar patrons demanding “Free Bird,” playing in a band had genuine moments of high comedy.

FLY LIKE AN EAGLE

Meanwhile, way out west in Los Angeles, Mudcrutch were recording tracks for Shelter Records, and Don Felder was officially a member of the Eagles, soon after the band listened to his guitar work on two tracks, “Good Day in Hell” and “Already Gone.” At twenty-seven years old Felder was a veteran of playing and recording music, a consummate guitarist with an intense drive and work ethic that was beginning to pay off. Ten years previously, Bernie Leadon had asked Buster Lipham the name of the best guitarist in town; ten years later record producer Bill Szymczyk asked the Eagles if they knew of “any good incendiary guitar players” who might bring the group’s sound closer in style to the big guitar-driven sounds of Led Zeppelin and the Who. In both cases the answer to the question was Don Felder.

The first day in the studio, Bernie greeted his bandmate from the Maundy Quintet days, and Felder wondered later if Leadon had mixed feelings about his arrival and Glenn Frey’s stated intent of steering the band away from country and toward rock. To put it in Felder’s own words, “Glenn wanted to speed things up and Bernie wanted to slow things down.” On the Border was released in March of 1974 and within two months had achieved gold record status, the Eagles’ fastest-selling album yet, with “The Best of My Love” reaching number one and selling more than a million. Now, two Gainesville boys were in a chart-topping band.

By the end of the year, the Eagles began work on a new album, One of These Nights, with Felder arranging the title track’s intro and bass guitar part as well as playing “incendiary” guitar. Bernie Leadon, however, was increasingly downhearted with the direction the Eagles were taking and with his diminishing role as a songwriter and founding member. Change was in the air.