CHAPTER 26

Mountains and Valleys

P

ENETRATING INTO

CANAAN AND ESTABLISHING ITSELF AS AN INDEPENDENT

state didn’t solve the problem of cosmic geography for Israel.

1

If anything, it sharpened the conflict. Not only was Israel surrounded by hostile nations and their gods, but there were also pockets of divine resistance from within.

The period of the judges and the monarchy form a tale of military and spiritual struggle. On the ground, the Israelites were still hamstrung by the presence of the vestiges of the Rephaim/Nephilim who had escaped annihilation in the conquest and by incursions from enemies on the peripheries. Toward the end of the last chapter I briefly noted Joshua 11:21–23, which informed us that the eradication of the Anakim had not been total. The writer of Joshua noted in that passage that some Anakim were known to live in cities that would later become cities of the Philistines—Israel’s chief enemy during the united monarchy. Spiritually, these conflicts had high stakes, as they signaled the infiltration of other gods siphoning off Israelite worshipers into their own cults. Since believing loyalty to Yahweh was foundational to Yahweh’s protection and remaining in the land, the spiritual battle was just as much a threat as the physical one.

The books of Judges, Samuel, and Kings clearly describe the military conflict. That’s the one that’s easy to see through modern eyes and with a modern worldview. But beneath the surface there’s a war of a different nature raging. We’ll cover a few examples in this chapter.

HOLY GROUND

When Moses was told to construct the tabernacle and its equipment, the Bible tells us that God revealed a pattern for doing so (“And you will erect the tabernacle according to its plan, which you have been shown on the mountain”—Exod 26:30). Earlier, in chapter 22

, we discussed how the tabernacle description aligned with divine abodes of other gods, namely from Ugarit. We need to revisit the tabernacle here, since its history prepares us for the more permanent temple—the place where the Name would dwell.

The implication of God having Moses follow a divine pattern is that the tabernacle tent structure on earth was to be a copy of the heavenly tent—as in heaven, so on earth. The heavenly tent prototype was the heavens themselves, as Isaiah 40:22 tells us (“He is the one who sits above the circle of the earth, and its inhabitants are like grasshoppers; the one who stretches out the heavens like a veil and spreads them out like a tent to live in”). In other words, the heavens and earth were conceived of as Yahweh’s true tabernacle or temple. The earthly dwelling place erected by the Israelites mimicked the grand habitation of the cosmos.

2

The tabernacle was not only the abode of Yahweh; it was also his throne room. Yahweh sits above the circle of the earth, in his heavenly tent, on his throne above the waters that are above “the firmament,” and rests his feet on the earth (“Thus says the LORD

: ‘Heaven is my throne, and the earth is my footstool’ ”—Isaiah 66:1

ESV

).

3

The ark of the covenant was there, the sacred object associated with Yahweh’s presence—his Name.

4

The tabernacle traveled with Israel during the entire journey to the promised land. Once Israel penetrated the land, the ark of the covenant (and therefore the tabernacle structure) was situated at Bethel (Judg 20:27), a name that means “house of God.” You know Bethel by now. It was the place where Jacob had his encounter with Yahweh and the angels of his council atop the “ladder” (i.e., a ziggurat; Gen 28:10–22). It was the place where the “angels of God” appeared to him again when he was fleeing from Esau, his brother (32:1–5). It was the place where Jacob built an altar and a pillar to commemorate the appearance of the visible Yahweh (31:13; cf. 35:1–7).

5

Sometime later the tabernacle moved from Bethel to Shiloh. Once that move occurred, it was said that the “house of God” was Shiloh (Judg 18:31; 1 Sam 1:24; Jer 7:12). The Old Testament indicates that Shiloh became the place of sacrifice (Judg 21:19; 1 Sam 1:3). At Shiloh we see the boy Samuel encounter the physicalized Yahweh, the Word (1 Sam 3

).

Eli the priest later foolishly sent the ark of the covenant out to battle, and it fell into the hands of the Philistines, who took it to Ashdod and installed it in the temple of their god, Dagon. In a fascinating (and funny) incident of cosmic geography, Yahweh’s presence destroyed the statue of Dagon. First Samuel 5:5 describes the reaction of the Philistine priests: “Therefore the priests of Dagon and all who come into the house of Dagon do not tread on the threshold of Dagon in Ashdod until this very day.” This threshold was now Yahweh’s geography—they dared not walk on it.

6

Eventually the ark was brought to Jerusalem. At first, David placed it in

a temporary tent he had made for it (2 Sam 6:17; 2 Chr 1:3–4), under the assumption that he was going to build a temple for it.

7

Like the tabernacle, the temple contains striking imagery associated with Eden. Eden was a lush garden and a holy mountain.

8

The tabernacle’s tent enclosure contained furnishings and decorations that evoked Edenic imagery.

9

All of these motifs—tent, mountain, garden—come together in the temple, the fixed place where Yahweh was considered to dwell and order the earth and the heavens with his council.

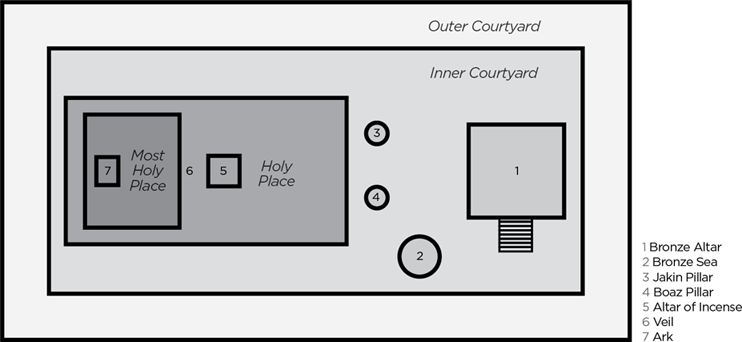

THE TEMPLE AS COSMIC TENT DWELLING

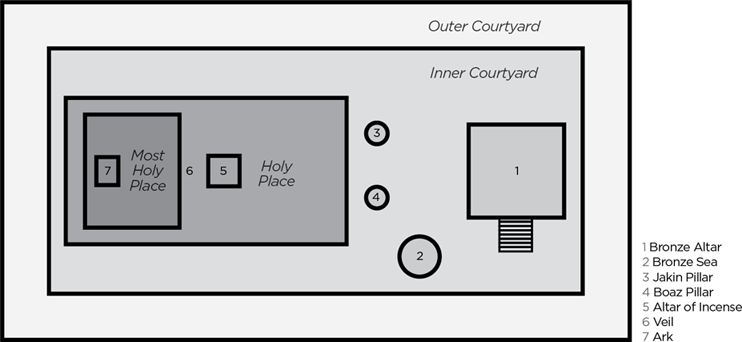

Many Bible readers assume that once the temple was built the tabernacle was forgotten or perhaps permanently dismantled. In reality, the tabernacle tent, with its holy of holies, was moved into the temple with the ark

.

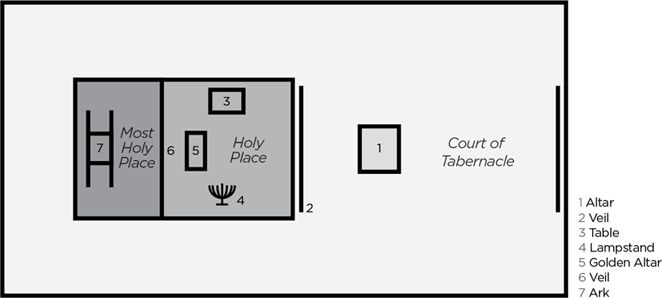

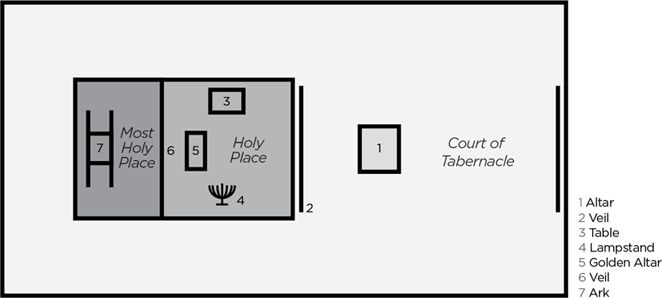

Recall that within the tabernacle was another building, completely covered with curtains, called the holy place. This room was divided in two by a veil, behind which was the holy of holies, the room that contained the ark (Exod 26

).

The inside of the temple also had this same type of inner room arrangement.

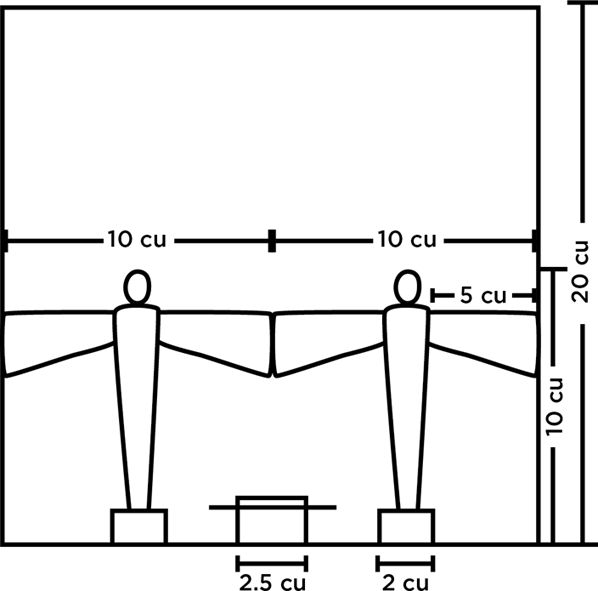

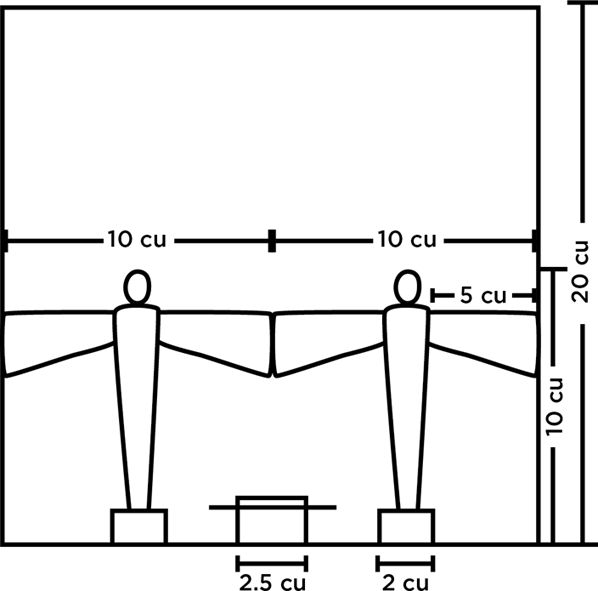

There was one major difference, though, between the inner sanctum of the temple and that of the tabernacle. The inner area of the temple had two giant cherubim in it, standing side by side, the tips of their wings stretching across to touch each other, like so:

The effect of this was that the cherubim wings formed the seat of a throne for Yahweh, and the ark was his footstool. The width and height dimensions between the cherubim can accommodate the size of the tented holy of holies. This has led some scholars to theorize that the tented holy of holies was moved

inside the temple, erected under and between the cherubim.

10

In the temple, the imagery of Yahweh on his throne and “living” in the ancient tent were both preserved.

11

THE TEMPLE AS COSMIC MOUNTAIN AND GARDEN

The Temple of Yahweh in Israel was naturally associated with a cosmic mountain dwelling like Sinai because it was situated in Jerusalem on Mount Zion, the new Sinai.

12

Psalm 48

makes this quite clear:

1

Great is the LORD

and greatly to be praised

in the city of our God!

His holy mountain

, 2

beautiful in elevation,

is the joy of all the earth,

Mount Zion

, in the far north [Lit.: heights of the north]

,

the city of the great King (Psa 48:1–2

ESV

).

Zechariah 8:3 (

ESV

) echoes the same notion: “Thus says the LORD

: I have returned to Zion and will dwell [literally, “will tabernacle”;

shakan

] in the midst of Jerusalem, and Jerusalem shall be called the faithful city, and the mountain of the LORD

of hosts, the holy mountain.”

As anyone who has been to Jerusalem knows, Mount Zion isn’t much of a mountain. It certainly isn’t located in the geographical north—it’s actually in the southern part of the country. So what’s meant by “the heights of the north”?

This description would be a familiar one to Israel’s pagan neighbors, particularly at Ugarit. It’s actually taken out of their literature. The “heights of the north” (Ugaritic: “the heights of

tsaphon

”) is the place where Baal lived and, supposedly, ran the cosmos at the behest of the high god El and the divine council.

13

The psalmist is stealing glory from Baal, restoring it to the One to whom it rightfully belongs—Yahweh. It’s a theological and literary slap in the face, another polemic.

This explains why the description sounds odd in terms of Jerusalem’s actual geography. This is why Isaiah and Micah used phrases like “the mountain of the house of Yahweh” (Isa 2:2; Mic 4:1). The description is designed to make a theological point, not a geographical one. Zion is the center of the cosmos, and Yahweh and his

council are its king and administrators, not Baal.

The temple is also the Edenic garden, full of lush vegetation and animals. The description of the temple’s construction in 1 Kings 6–7

is explicit in this regard.

14

Flowers, palm trees, gourds, cypress trees, cherubim, lions, and pomegranates all adorn the temple via its carved architectural features.

In Ezekiel’s vision of the new temple (Ezek 40–48

), he saw a temple built

on a high mountain (40:2), whose courts were decorated with palm trees (40:31–34). The interior was decorated with more palm trees and cherubim (41:17–20.). Ezekiel’s temple-garden was well watered, like Eden, since a river flowed from it that supernaturally gave life to everything else (47:1–12).

In Israel’s theology, Eden, the tabernacle, Sinai, and the temple were equally the abode of Yahweh and his council. The Israelites who had the tabernacle and the temple were constantly reminded of the fact that they had the God of the cosmic mountain and the cosmic garden living in their midst, and if they obeyed him, Zion would become the kingdom domain of Yahweh, which would serve as the place to which he would regather the disinherited nations cast aside at Babel to himself. Micah 4

puts it well:

1

It shall come to pass in the latter days

that the mountain of the house of the LORD

shall be established as the highest of the mountains,

and it shall be lifted up above the hills;

and peoples shall flow to it,

2

and many nations shall come, and say:

“Come, let us go up to the mountain of the LORD

,

to the house of the God of Jacob,

that he may teach us his ways

and that we may walk in his paths.”

For out of Zion shall go forth the law,

and the word of the LORD

from Jerusalem (Mic 4:1–2

ESV

).

UNHOLY GROUND

In stark contrast to the temple, the place in Israel’s cosmic-geographical thinking where heaven and earth intersected, there were sinister places within Canaan that became associated with the powers of darkness, specifically the vestiges of the Rephaim/Nephilim bloodlines.

In our earlier discussion of the conquest we came across the Rephaim. The Rephaim were giants. Deuteronomy informed us that the Anakim were considered Rephaim (Deut 2:11), as were the Zamzummim (Deut 2:20). Og of Bashan “was left from the remnant of the Rephaim” (Deut 3:11), so that “Bashan was called the land of the Rephaim” (Deut 3:13).

Joshua 11:22 tells us that the conquest had failed to eliminate all the Anakim, that some remained in the Philistine cities of Gaza, Gath, and Ashdod. The Rephaim presence persisted in the land until the time of David. The giant Goliath, who came from Gath (1 Sam 17:4, 23), was a descendant

of the refugee Anakim/Rephaim. He had brothers, too, as we learn in 1 Chronicles 20

:

4

And after this there arose a war in Gezer with the Philistines. Then Sibbecai the Hushathite struck down Sippai, one of the descendants of the Rephaim. And they were subdued. 5

And again there was war with the Philistines. And Elhanan son of Jair struck down Lahmi, the brother of Goliath the Gittite, the shaft of whose spear was like a weaver’s beam. 6

And again there was war in Gath. And there was a very tall man there, and he had six fingers on each hand and six toes on each foot, twenty-four in all. He himself was also a descendant of the Rephaim. 7

And he taunted Israel, but Jehonathan son of Shimea, brother of David, struck him down. 8

These were born to the giants in Gath, and they fell by the hand of David and by the hand of his servants (vv. 4–8).

The Rephaim of the Transjordan in the days of Moses were associated not only with Bashan but also Ashtaroth and Edrei, two cities that, in the literature of Ugarit, were considered as marking the gateway to the underworld. In David’s time, the Rephaim were also associated with death in a more peripheral, but conceptually similar, way.

There are nearly ten references in the Old Testament to a place known as the Valley of the Rephaim. On several occasions the Philistines are described as camped there (2 Sam 5:18, 22; 23:13).

15

Joshua 15:8 and 18:16 tell us that the Valley of the Rephaim adjoined another valley—the Valley of Hinnom, also known as the Valley of the Son of Hinnom.

16

In Hebrew “Valley of Hinnom” is

ge hinnom

, a phrase from which the name gehenna derives.

In New Testament times, gehenna had become a designation for the fiery realm of the dead—hell or Hades. The history of the Valley of Hinnom no doubt was part of the reason for this conception. The translated meaning of

ge hinnom

in Hebrew is most likely “valley of wailing,” an understandable description given the child sacrifice that took place there. The Valley of

Hinnom was the place where King Ahaz and King Manasseh sacrificed their own sons as burnt offerings to Molech (2 Chr 28:3; 33:6). These sacrifices took place at ritual centers called

topheth

(“burning place”), and later the Valley of Hinnom became referred to by the place name Tophet (Jer 7:32; 19:6).

The meaning and identity of Molech (Hebrew consonants, m-l-k) is hotly debated by scholars.

17

It is hard to see one clear association, however, as coincidental. Molech’s name appears in two snake charms from Ugarit in connection with the city of Ashtaroth (Ugaritic:

ʿ ṯṯrt

), the place known from the biblical accounts about Og (Deut 1:4; 9:10; 12:4).

18

Another Ugaritic text puts the god Rpu, the patron deity of the Rephaim, in Ashtaroth as well. These texts at the very least inform us that there was a close religious association between Molech and the Rephaim. This makes sense in light of the geographical relationship between the Valley of the Rephaim and the Valley of Hinnom in the Old Testament.

What’s particularly fascinating—or disturbing—is that the location of these valleys is directly adjacent to the southern side of Jerusalem, Mount Zion, the place of Yahweh’s presence in his temple.

THE SPIRITUAL VALLEY

These examples are just a sampling of the cosmic-geographical worldview of the biblical writers and their times. Spiritual conflict lurks behind a wide range of Old Testament episodes and practices. The conflict between the powers of darkness and the presence of Yahweh was an ever-present part of life for the ancient Israelite. Unfortunately, the biblical record is riddled with examples of Israelites being seduced by or embracing those powers.

Israel enjoyed a united monarchy—meaning that all twelve tribes were united under one king—through the reigns of Saul, David, and Solomon. The enterprise began poorly. The Israelites’ demand for a king (1 Sam 8

) was not a call for someone who would administer righteousness within the country and bring stability. Rather, it was a rejection of Yahweh’s ability to fight for his obedient people (1 Sam 8:20). The divine warrior of the exodus and wars against the Anakim had been cast aside for—ironically—the tallest person on

the Israelite side (1 Sam 9:2). “Make us a king like the other nations!” God gave them what they asked for, and they paid the price.

Eventually the kingdom solidified under David, the man after God’s own heart. In fact, God had picked him out specifically for the task (1 Sam 16

) and validated his status with a victory over a Rephaim giant (Goliath) in single combat. God went so far as to initiate a covenant with David, declaring that only David’s descendants would be legitimate heirs of his kingship (2 Sam 7

).

That succession lasted one generation, through the kingship of Solomon. Once Solomon was gone, the kingdom split into two kingdoms: Israel (ten tribes) to the north and Judah (two tribes), with its capital in Jerusalem. It was only a matter of time before each of them succumbed to idolatrous disloyalty to Yahweh. In the northern kingdom, it happened immediately. Jeroboam, Israel’s first rebel king, made a rebuilt Shechem his first capital city (1 Kgs 12:25). Shechem had been the place where Joshua had gathered Israel before his death to dedicate the nation to finishing the conquest and remaining pure before Yahweh (Josh 24

). Jeroboam set up cult centers (1 Kgs 12:26–33) for Baal worship in two places to mark the extent of his realm: Dan (which was in the region of Bashan, close to Mount Hermon) and Bethel (the place where Yahweh had appeared to the patriarchs).

19

The symbolism of spiritual warfare in these decisions was palpable. No one faithful to Yahweh would have missed their intended contempt. Ten of Israel’s tribes were now under the dominion of other gods. Yahweh would destroy Israel in 722

via the Assyrian Empire.

Judah, the southern kingdom, ostensibly loyal to David and Yahweh, would also fail. They too would have kings who turned from Yahweh. The Davidic dynasty eventually collapsed and Judah’s people were sent into exile in—of all places—Babylon.

We mustn’t conclude that God didn’t try to turn the hearts of his people back to himself. That’s precisely why he raised up prophets—after they had met with him and his council.