CHAPTER 32

Preeminent Domain

I

N THE PREVIOUS CHAPTER WE SAW THAT THE ARRIVAL OF

JOHN THE

BAPTIST

and Jesus the messiah played out against the backdrop of a divine council passage found in Isaiah 40

. While the episodes of John’s appearance and Jesus’ baptism are familiar, the theological framework provided by Isaiah is easy to miss.

The supernatural context of Jesus’ actions and statements also frequently goes unnoticed. We have space to share only a few examples. The cosmic backdrop of the divine council worldview of the Old Testament to which you’re now acclimated will make them quite discernible. Even though they are too often taught that way, the Gospels are far more than a boring point-to-point travelogue. Consider this chapter a cure.

THIS IS MY FATHER’S WORLD

In the last chapter we saw how the Gospels portrayed the baptism of Jesus as a new exodus. The exodus, of course, was the precursor to reviving the kingdom of God in the land of promise. Israel danced while Moses sang out, “Who is like Yahweh among the gods?” As Moses led Israel through the watery chaos and the unholy ground of other gods, so Jesus, “the prophet like Moses” (Acts 3:22; 7:37), first came through the waters (his baptism) before launching the kingdom.

This mission was not only about the single land and people of Israel, whom Yahweh had created after consigning the existing nations to the dominion of lesser gods at Babel. The coming of the incarnate Yahweh was the beginning of reclaiming those nations as well

. But the gods of darkness were not going to surrender their domains without a fight—and the battle began so quickly that Jesus barely had time to dry off.

The gospel writers tell us the event that immediately followed Jesus’ baptism

was his journey into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil at the direction of the Holy Spirit (Matt 4:1; Mark 1:12; Luke 4:1–13). Think about the location: the wilderness.

The term obviously refers to a literal place, most likely the wilderness of Judea (Matt 3:1), but it’s also a metaphor for unholy ground.

We’ve seen this in one particular instance. Conceptually, the wilderness was where Israelites believed “desert demons,” including Azazel, lived. The Azazel material is especially telling, since, as I noted in our earlier discussion, Jewish practice of the Day of Atonement ritual in Jesus’ day included driving the goat “for Azazel” into the desert outside Jerusalem and pushing it over a cliff so it could not return.

1

The wilderness was a place associated with the demonic, so it’s no surprise that this is where Jesus meets the devil.

But why would the Spirit compel Jesus to go into the desert to face the devil? The answer takes us back to the previous chapter and the Gospels’ presentation of Jesus’ baptism and revival of God’s kingdom as a new exodus event. In the Old Testament, Israel, the son of God (Exod 4:23), passed through the sea (Exod 14–15

) and then ventured out into the wilderness on the way to Canaan to re-establish Yahweh’s kingdom. But Israel’s faith and loyalty to Yahweh faltered (Judg 2:11–15). They were eventually seduced by the hostile divine powers (“demons”) whose domain was the wilderness (Deut 32:15–20). Jesus, the messianic son of God and royal representative of the nation, would succeed where Israel failed. As R. T. France

notes:

The most significant key to the understanding of this story is to be found in Jesus’ three scriptural quotations. All come from Deut 6–8

, the part of Moses’ address to the Israelites before their entry into Canaan in which he reminds them of their forty years of wilderness experiences. It has been a time of preparation and of proving the faithfulness of their God. He has deliberately put them through a time of privation as an educative process. They have been learning, or should have been learning, what it means to live in trusting obedience to God.… Now another “Son of God” is in the wilderness, this time for forty days rather than forty years, as a preparation for entering into his divine calling. There in the wilderness he too faces those same tests, and he has learned the lessons which Israel had so imperfectly grasped. His Father is testing him in the school of privation, and his triumphant rebuttal of the devil’s suggestions will ensure that the filial bond can survive in spite of the conflict that lies ahead. Israel’s occupation of the promised land was at best a flawed fulfillment of the hopes with which they came to the Jordan, but this

new “Son of God” will not fail and the new Exodus (to which we have seen a number of allusions in ch. 2

) will succeed. “Where Israel of old stumbled and fell, Christ the new Israel stood firm.… The story of the testing in the wilderness is thus an elaborate typological presentation of Jesus as himself the true Israel, the ‘Son of God’ through whom God’s redemptive purpose for his people is now at last to reach its fulfillment.”

2

In the first temptation of Jesus, Satan tried to entice him into satisfying his hunger by turning stones to bread. The problem of hunger was, of course, an issue in Israel’s wanderings in the wilderness on the way to Canaan. Jesus responds by quoting Deuteronomy 8:3, which reads in context, “And [Yahweh] humbled you and let you go hungry, and then

he fed you with that which you did not know nor did your ancestors know, in order to make you know that not by bread alone but by all that

goes out of the mouth of Yahweh humankind shall live.” Jesus’ point was that his loyalty was to the invisible Yahweh alone; he would obey no other.

The second temptation was like the first. Satan dared Jesus to jump from the top of the temple to prove he was the son of God, whom God’s angels would protect. Jesus quotes Deuteronomy 6:16, which again is in the context of obedience to Yahweh alone: 16

“You shall not put Yahweh your God to the test, as you tested him at Massah. 17

You shall diligently keep the commandments of Yahweh your God and his legal provisions and his rules that he has commanded you” (Deut 6:16–17).

The ultimate temptation comes last, and hits directly at Jesus’ ultimate mission—to reclaim the nations that are rightfully Yahweh’s:

8

Again the devil took him to a very high mountain and showed him all the kingdoms of the world and their glory, 9

and he said to him, “I will give to you all these things, if you will fall down and worship me” (Matt 4:8–9).

Satan offered Jesus the nations that had been disinherited by Yahweh at Babel. Coming from the “ruler of this world” (John 12:31), the offer was not a hollow one. As the original rebel, the

nachash

of Genesis 3

(cf. Rev 12:9) had, by New Testament times, achieved the status of the lead opposition to Yahweh.

3

This was part of the logic of attributing the term

saṭan

to him as a proper

personal name. Recall as well that the

nachash

has been cast down to the

ʾerets

, a term that referred not only to “earth” but also the realm of the dead, Sheol.

4

The “original rebel,” whose domain became earth/Sheol,

nachash

/Satan was perceived by Second Temple and New Testament theology as primary authority over all other rebels and their domains. Consequently, his lordship over the gods who ruled the nations in the Deuteronomy 32

worldview of the Old Testament was presumed.

Had Jesus given in, it would have been an acknowledgment that Satan’s permission was needed

to possess the nations. It wasn’t. Satan presumed power and ownership of something that, ultimately, was not his but God’s. The messaging behind Jesus’ answer is clear: Yahweh will take

the nations back by his own means in his own time. He doesn’t need them to be given away in a bargain. Jesus was loyal to his Father. Since reclaiming the nations was connected with salvation and redemption from the effects of the fall in Eden, accepting Satan’s offer would have undermined the necessity of the atonement of the cross.

5

GAME ON

Immediately following this confrontation, Jesus “returned in the power of the Spirit to Galilee,” where he preached in the region’s synagogues and was rejected by those in his home town of Nazareth (Luke 4:14–15). Matthew and Mark tell us that Jesus moved out of Nazareth and went to live in Capernaum (Matt 4:12–16). At Capernaum he began his ministry with a simple but appropriate message: “Repent, because the kingdom of heaven is near” (Matt 4:17). Jesus then did two things: called his first disciples (Peter, Andrew, James, and John) and healed a demon-possessed man (Mark 1:16–28; Luke 4:31–5:11

). Let the holy war begin.

6

It might sound hard to believe, but this event is first time in the entire Bible we read about a demon being cast out of a person. No such event is ever recorded in the Old Testament. The defeat of demons, falling on the heels of Jesus’ victory over Satan’s temptations, marks the beginning of the re-establishment of the kingdom of God on earth. Jesus himself made this connection absolutely explicit: “If it is by the finger of God that I cast out demons, then the kingdom of God has come upon you” (Luke 11:20

ESV

). And since the lesser

elohim

over the nations are cast as demons in the Old Testament, the implications for our study are clear: The ministry of Jesus marked the beginning of repossession of the nations and defeat of their

elohim

.

7

In Luke’s account, Jesus preaches, heals, and casts out more demons after this initial exorcism. He also gathers more disciples. In Luke 9

, Jesus gathers his twelve disciples together and gives them power and authority over the demons, sending them out to proclaim the kingdom of God (9:1–6). The symbolic telegraphing of choosing twelve

disciples (one to correspond to each of the tribes of Israel

, Yahweh’s domain) is evident.

As if the intention wasn’t clear enough, in the next chapter Jesus does something dramatic to announce to all who understood the cosmic geography of Babel what was really happening:

After this the Lord appointed seventy others and sent them on ahead of him in pairs to every town and place where He Himself was going to come (Luke 10:1

NRSV

).

Jesus sent out seventy

disciples. The number is not accidental.

8

Seventy is the

number of nations listed in Genesis 10

that were dispossessed at Babel. The seventy “return with joy” (Luke 10:17) and announce to Jesus, “Lord, even the demons are subject to us in your name!” Jesus’ response is telling: “I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven” (10:18). The implications are clear: Jesus’ ministry is the beginning of the end for Satan and the gods of the nations. The great reversal is underway.

9

GROUND ZERO: The Gates of Hell

The spiritual skirmishes against the powers of darkness are evident throughout Jesus’ ministry. One of the more dramatic is described in Matthew 16:13–20. Jesus goes with his disciples to the district of Caesarea Philippi. On the way he asks the famous question, “Who do people say that I am?” Peter answers, “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.” Jesus commends Peter:

Blessed are you, Simon Bar-Jonah! For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father who is in heaven. 18

And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it (Matt 16:17–18

ESV

).

This passage is among the most controversial in the Bible, as it is a focal point of debate between Roman Catholics, who reference it to argue that the passage makes Peter the leader of the original church (and thus the first pope) and those who oppose that idea. There’s actually something much more cosmic

going on here. The location of the incident—Caesarea Philippi—and the reference to the “gates of hell” provide the context for the “rock” of which Jesus is speaking.

The location of Caesarea Philippi should be familiar from our earlier discussions about the wars against the giant clans.

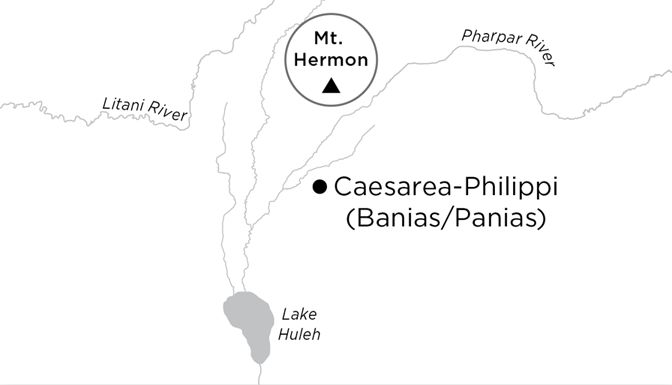

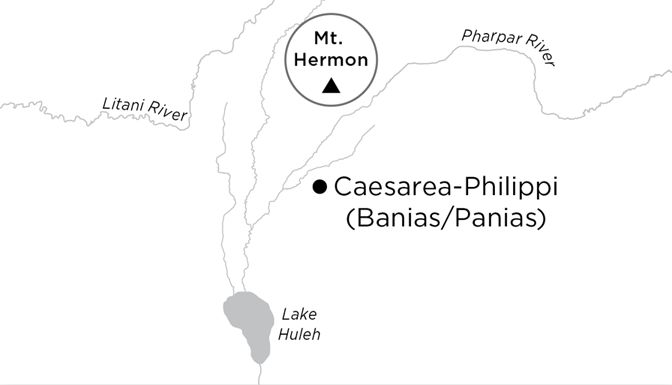

Caesarea Philippi is adjacent to the Pharpar River. Noting this geography, we can see exactly where Jesus was when he uttered the famous words about “this rock” and the “gates of hell” to Peter.

Caesarea Philippi was located in the northern part of the Old Testament region of Bashan, the “place of the serpent,” at the foot of Mount Hermon.

10

Things hadn’t changed much by Jesus’ day, at least in terms of spiritual control. You may have noticed on these maps that Caesarea Philippi was also called “Panias.” The early church historian Eusebius notes: “Until today the mount in front of Panias and Lebanon is known as Hermon and it is respected by nations as a sanctuary.”

11

The site was famous in the ancient world as a center of the worship of Pan and for a temple to the high god Zeus, considered in Jesus’ day to be incarnate in Augustus Caesar.

12

As one authority notes:

More than twenty temples have been surveyed on Mt. Hermon and its environs. This is an unprecedented number in comparison with other regions of the Phoenician coast. They appear to be the ancient cult sites of the Mt. Hermon population and represent the Canaanite/Phoenician concept of open-air cult centers dedicated, evidently, to the celestial gods.

13

The reference in the quotation to “celestial gods” takes our minds back to the “host of heaven,” the sons of God who were put in authority over the nations at Babel (Deut 32:8–9) who were not to be worshiped by Israelites (Deut 4:19–20; 17:3; 29:25).

The basis for Catholicism’s contention that the Church is built on Peter’s leadership is that his name means “stone.”

14

For sure there is wordplay going on in Peter’s confession, but I would suggest there is also an important double entendre: the “rock” refers to the mountain location

where Jesus makes the statement. When viewed from this perspective, Peter confesses Jesus as the Christ, the Son of the living God, at “this rock” (this mountain

—Mount Hermon). Why? This place was considered the “gates of hell,” the gateway to the realm of the dead, in Old Testament times.

15

The theological messaging couldn’t be more dramatic. Jesus says he will build his church—and the “gates of hell” will not prevail against it. We often

think of this phrase as though God’s people are in a posture of having to bravely fend off Satan and his demons. This simply isn’t correct. Gates are defensive structures, not offensive weapons. The kingdom of God is the aggressor.

16

Jesus begins at ground zero in the cosmic geography of both testaments to announce the great reversal. It is the gates of hell that are under assault

—and they will not

hold up against the Church. Hell will one day be Satan’s tomb

.

BAITING THE ENEMY

It’s hard to imagine, but the conflict ratchets up one more notch after Peter’s confession.

Mount Hermon, as readers will recall, was the place where, in Jewish literature such as the book of 1 Enoch, the sons of God of Genesis 6:1–4 chose to launch their rebellion against Yahweh. Jesus had one more statement to make to his unseen enemies.

Matthew, Mark, and Luke all agree that the next event in the ministry of Jesus after Peter’s confession was the transfiguration:

2

And after six days Jesus took with him Peter and James and John, and led them up a high mountain by themselves. And he was transfigured before them, 3

and his clothes became radiant, intensely white, as no one on earth could bleach them. 4

And there appeared to them Elijah with Moses, and they were talking with Jesus. 5

And Peter said to Jesus, “Rabbi, it is good that we are here. Let us make three tents, one for you and one for Moses and one for Elijah.” 6

For he did not know what to say, for they were terrified. 7

And a cloud overshadowed them, and a voice came out of the cloud, “This is my beloved Son; listen to him.” 8

And suddenly, looking around, they no longer saw anyone with them but Jesus only (Mark 9:2–8

ESV

).

We’ve already learned the significance of “beloved” with respect to Jesus—that it is a divinely affixed title marking the rightful heir to David’s throne and, therefore, the kingdom of God on earth.

17

Our focus here is on the event itself.

In early church tradition, the location of the mount of transfiguration was believed by many to be Mount Tabor.

18

The earliest witness to this tradition

is the fourth century AD

.

19

The gospels themselves give no name, and so the tradition has no biblical precedent. Mount Hermon is also much higher than Tabor (8,500 feet vs. 1,843 feet), which would fit better with the description of a “high mountain” by Mark (and in Matt 17:1).

20

Some scholars still hold to the Tabor identification, but many have come to agree that the close proximity of Caesarea Philippi to Mount Hermon and the symbolic-religious associations that relationship entails make Mount Hermon the logical choice for the transfiguration.

21

The imagery is striking. We’ve seen already that the Jewish tradition about the descent of the Watchers, the sons of God of Genesis 6:1–4, informed the writings of Peter and Jude. Now we see that the transfiguration of Jesus takes place on the same location identified by that tradition. Jesus picks Mount Hermon to reveal to Peter, James, and John exactly who he is—the embodied glory-essence of God, the divine Name made visible by incarnation. The meaning is just as transparent: I’m putting the hostile powers of the unseen world on notice. I’ve come to earth to take back what is mine. The kingdom of God is at hand.

The account of Peter’s confession at the foot of Mount Hermon and the revelation of the transfiguration on its unholy slopes marked a key transition point in Jesus’ life, particularly as the Gospel of Mark presents it. After he throws down the gauntlet at the transfiguration, he begins to move toward Jerusalem to his death. One scholar puts it this way:

Mark not only presents a consistent and historically probable account of the movements of Jesus during the last weeks or months of his life … indeed there is good reason for accepting the account as historically accurate. How long the period was cannot be determined. But it begins with Peter’s Confession near Caesarea Philippi and a practically simultaneous conviction or announcement on Jesus’ part that he could not expect such recognition from the multitudes or the authorities, but that he must appear in Jerusalem and there in some

way or measure suffer the woes of the last days before the kingdom of God could come.

22

The enemy knows who Jesus is, but, as noted earlier, the forces of darkness do not know the plan.

23

Jesus has baited them into action, and act they will. He has given them the rope, and they will eagerly hang themselves with it. Jesus will go to Jerusalem to drink from the cup that the Father has planned for him. But the instrument of death will be the catalyst that launches the kingdom of God in its full force.