“… regnare deum super omnia Christum,

qui cruce dispensa per quattuor extima ligni

quattuor adtingit dimensum partibus orbem,

ut trahat ad uitam populos ex omnibus oris.”

(Christ reigns over all things as God, who, on the outstretched cross, reaches out through the four extremities of the wood to the four parts of the wide world, that he may draw unto life the peoples from all lands.) (Carmina, ed. by Wilhelm Hartel, Carm. XIX, 639ff., p. 140.) For the Cross as God’s “lightning” cf. “A Study in the Process of Individuation,” pars. 535f.

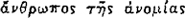

(man of lawlessness) and the

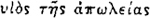

(man of lawlessness) and the  (son of perdition) who herald the coming of the Lord. This “lawless one” will set himself up in the place of God, but will finally be slain by the Lord Jesus “with the breath of his mouth.” He will work wonders

(son of perdition) who herald the coming of the Lord. This “lawless one” will set himself up in the place of God, but will finally be slain by the Lord Jesus “with the breath of his mouth.” He will work wonders

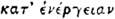

(according to the working of Satan). Above all, he will reveal himself by his lying and deceitfulness. Daniel 11 : 36ff. is regarded as a prototype.

(according to the working of Satan). Above all, he will reveal himself by his lying and deceitfulness. Daniel 11 : 36ff. is regarded as a prototype.

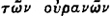

(The kingdom of God is within you [or “among you”]). “The kingdom of God cometh not with observation: neither shall they say, Lo here! or, lo there!” for it is within and everywhere. (Luke 17 : 20f.) “It is not of this [external] world.” (John 18 : 36.) The likeness of the kingdom of God to man is explicitly stated in the parable of the sower (Matthew 13 : 24. Cf. also Matthew 13 : 45, 18 : 23, 22 : 2). The papyrus fragments from Oxyrhynchus say: …

(The kingdom of God is within you [or “among you”]). “The kingdom of God cometh not with observation: neither shall they say, Lo here! or, lo there!” for it is within and everywhere. (Luke 17 : 20f.) “It is not of this [external] world.” (John 18 : 36.) The likeness of the kingdom of God to man is explicitly stated in the parable of the sower (Matthew 13 : 24. Cf. also Matthew 13 : 45, 18 : 23, 22 : 2). The papyrus fragments from Oxyrhynchus say: …  [

[

]

]  [

[ ]

] [

[

]

]

[

[ ]

]

. (The kingdom of heaven is within you, and whosoever knoweth himself shall find it. Know yourselves.) Cf. James, The Apocryphal New Testament, p. 26, and Grenfell and Hunt, New Sayings of Jesus, p. 15.

. (The kingdom of heaven is within you, and whosoever knoweth himself shall find it. Know yourselves.) Cf. James, The Apocryphal New Testament, p. 26, and Grenfell and Hunt, New Sayings of Jesus, p. 15. [

[ ]

]

,

,

.), while his mother, “being left behind in the shadow, and deprived of spiritual substance,’ there gave birth to the real “Demiurge and Pantokrator of the lower world.’ But the shadow which lies over the world is, as we know from the Gospels, the princeps huius mundi, the devil. Cf. The Writings of Irenaeus, I, pp. 45f.

.), while his mother, “being left behind in the shadow, and deprived of spiritual substance,’ there gave birth to the real “Demiurge and Pantokrator of the lower world.’ But the shadow which lies over the world is, as we know from the Gospels, the princeps huius mundi, the devil. Cf. The Writings of Irenaeus, I, pp. 45f. (grief); the male, of λoγ

(grief); the male, of λoγ (knowledge), and

(knowledge), and

…

…  . The reading

. The reading  . seems to me to make more sense.

. seems to me to make more sense. .

.

.

. (he who leads across), καρπ

(he who leads across), καρπ