Chapter 5

Finding Melodies Where You Least Expect Them

IN THIS CHAPTER

Understanding melodies and musical frameworks

Understanding melodies and musical frameworks

Discerning melodies in speech

Discerning melodies in speech

Picking out melodies from your environment

Picking out melodies from your environment

Getting the most out of the Muse

Getting the most out of the Muse

Seeking melodies through instruments

Seeking melodies through instruments

Exercising your melodies

Exercising your melodies

What exactly is a melody? Or, from a composer’s standpoint, perhaps a more important question is: Why do you need one (or several)? Where can you find them?

To answer the first question, putting it very, very simply: A melody is a succession of notes built on a musical framework.

A melody is probably the most important part of a composition. It’s the lead line you find yourself humming after hearing a song, and it’s the part of a song that seems to be the hardest to get out of your head.

Sounds simple enough. Maybe too simple, but it’s a good start.

What Is a Musical Framework?

Obviously, throwing a random succession of notes together will almost certainly not produce a good melody. Yet many successful compositions might sound to many listeners as though that’s just what the composer did. And believe it or not, there are tools available in several computer programs that will do just that — randomize notes into musical phrases (see Chapter 2 for a brief survey of music software).

Anyone, with or without the help of technology, can come up with a succession of notes. But what makes a good melody? And just what do we mean by a musical framework?

For one thing, a musical framework is the duration of a particular section of your composition. Or to be more abstract: A musical framework is the amount of time during which you are hoping to secure the attention of your listeners.

Because music is the sculpting of time, without a framework of some kind, you don’t have music. Many times, when you’re composing, the melody itself creates or even demands a framework to grow around it. Even a lonely, solitary melody has a little rhythm built into it. (The other elements of the musical framework are the chords and instrumentation that you have chosen, which we talk about in Part 3.)

Now, where do you find melodies to go into this framework?

Finding Melody in Language

If you are ever in need of inspiration, try slipping a recording device in your pocket and heading out into the street. Go into a cafe or get on the bus, turn on your recorder, and just let the din of the other passengers’ voices wash over you. You don’t even have to listen to the recording afterwards — oftentimes, just being an active listener can be enough to get you started in learning to pay attention to the music of language.

There is so much to get from the way a person talks. Consider the rhythm of a speaker’s voice — is it clumsy, staccato, languid, legato? What about the quality of a voice — high-pitched, low-pitched, childish, aggressive? Each person is a self-playing instrument. Put two or more people together, and you’ve got the most basic orchestra.

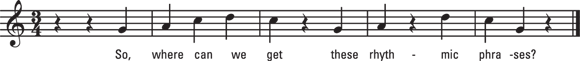

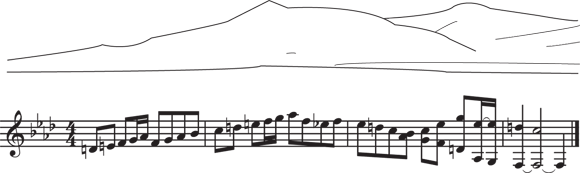

Take another look at the example of finding the rhythmic phrase in speech from Chapter 4 (Figure 5-1).

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-1: Rhythmic patterns are found everywhere in speech.

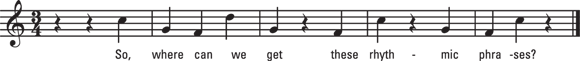

Looking at Figure 5-1, let’s see what kind of melody is suggested by this phrase. When you speak the phrase out loud, notice that some of the words rise upward in pitch, while others go down in pitch. There might be some variation in emphasis or intention when different people say the phrase, but by and large these words almost demand a natural melodic movement, something like that shown in Figure 5-2.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-2: Adding natural melodic movement to the phrase, based on the way the words rise and fall in speech.

All well and good. Now try speaking the phrase with an unnatural melodic movement, something like the one shown in Figure 5-3.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-3: Making the phrase sound wrong by adding unnatural melodic movement to it.

Now the phrase doesn’t work musically. The melody of it is off somehow. Or is it the rhythmic emphasis? See how important the elements of music are to basic spoken communications? It’s fairly easy to determine the direction that the melody wants to move in this example — and a direction where it doesn’t. We can see the basic landscape, given this phrase.

But where will we find the exact notes to give to our melody? One way would be to limit ourselves to the notes within a particular scale. In our examples, we’ve stuck to the key of C major and used notes that we know make musical sense together — that is, notes from the C major scale. So, using notes from the major scale is one very common method of finding notes.

Let’s Eat(,) Grandma!

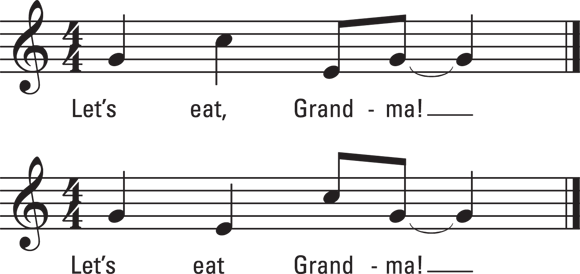

It’s fun and instructive to see how meanings can totally change depending solely on your melodic choices. Figure 5-4 shows three words with two different melodies.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-4: Two possible melodies show different possibilities from one spoken phrase.

The first version is an invitation to Grandma to join in the feast. The second one, though, sounds like an invitation for Grandma to be the feast. “Let’s eat, Grandma” is very different from “Let’s eat Grandma”!

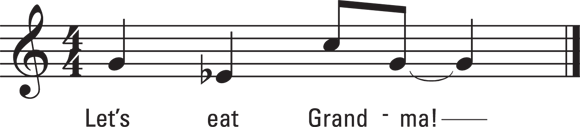

Going further, we could make the second version even darker and more threatening by using a minor scale instead of a major scale (Figure 5-5).

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-5: This is more a case of “Run, Grandma, run!”

As you can see, your choice of scale can contribute to the mood messages you are trying to convey in your music.

In the examples so far, we’ve stuck to using short phrases of language to make a point. But there is no reason why you couldn’t apply these ideas to an entire conversation — perhaps a musical transcription of your recorded bus trip.

If you are writing a song, it is essential to be respectful of the way your lyrics fit rhythmically and melodically with your music, but you don’t have to be a great lyricist to use a verbal idea as a source for your melodies. Maybe you will be the only one who knows that your famous composition started out as “Scrambled eggs, oh, baby how I love your legs” (Paul McCartney’s original lyrics for “Yesterday”).

Finding Melody in the World Around You

Just about every composer has found inspiration for a song from walking outside and blinking at the world at one point or another. Nature is a great source of inspiration; city sidewalks and noisy factories are others. Sometimes it’s just picking up the recurring rhythms of the environment and building a simple melody on top of that.

Other times, it can be as simple as stealing a bird’s song for your melody — or the quiet humming or muttering of someone walking past you on the street, or the varying pitches of a concrete saw whining across the street. Some composers even claim that when they see the throat of a newly opened flower, they hear singing in their heads. The inspiration for the greatest compositions in the world is all around you. Learning how to turn that inspiration into actual music is the challenge.

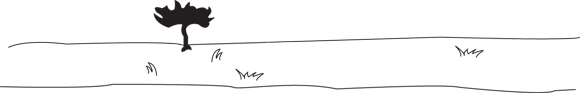

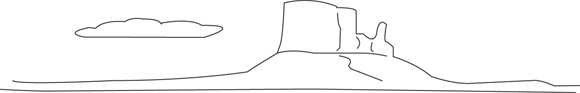

Sometimes composing a melody can be like creating a sonic dot-to-dot drawing. Many composers have attempted to recreate scenery, landscapes, cityscapes, and the activities of nature and humanity through their compositions, such as in Ferde Grofe’s “Grand Canyon Suite.” In fact, some melodies can be seen as literal landscapes on the musical staff. If you extract the basic melody from music, connect the notes on the staff, and hold it up in front of you, it looks like a dot-to-dot drawing of a scene.

If a melody is like a sonic painting of a landscape, the melody rises and dips into hills and valleys, sometimes quickly jumping up cliffs, and then just as suddenly diving into ravines.

Figures 5-6 through 5-9 show a few simple drawings. The first one has been transcribed into a melody for you. Pick a second one for you to do, and write the notes on the blank staff at the bottom of Figure 5-9.

We don’t expect you to be able to fully compose music yet. The preceding exercise is meant to show that you can draw inspiration and generally shape music around it.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-6: We translated this landscape into a melody that generally follows its contours.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-7: Here a landscape offers very subtle variation, suggesting a quiet, uncomplicated melody.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-8: This landscape has a strong, clearly shaped central feature, and so would music based on it.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-9: This is a kind of abstract, sparse “landscape,” offering a more or less regular pattern.

If you were to stop and think about your choices of notes and rhythms to represent these scenes, you might also want to consider representing other unseen elements within them. For example, what other sounds — birds, waterfalls, insects — might be present, and how can they be represented musically? What sort of emotion does each scene convey to you? How can you represent and refine that emotion through tempo, choice of scale (also called mode), and instrumentation?

The visual realm is not the only one from which you can draw melodic inspiration. What does touch sound like? Soft caresses must sound different from a slap in the face, right? What about taste — can you represent taste through musical composition? What makes a piece of music bland or flavorful? And let’s not forget the sense of smell. Can a musical composition smell sweet? We’ve certainly all heard a few that stink.

Helping Your Muse Help You

One can’t overestimate the value of a good musical imagination. It is the single most powerful source for making music — if you can tap into it. The imagination is so powerful, in fact, that since long ago it has been personified as the Muse.

Because it is inside your head, though, your imagination is also the hardest source to put your finger on. Its timing is sometimes off, for one thing. The Muse can feed you melodies when you least expect them and are least prepared to do anything about them.

You can do a few things to help your Muse work more effectively for you. Here are some things the Muse needs and ideas about how to do your part to help:

-

The Muse needs space to work in.

Turn off your TV and radio, log off the Internet, turn off your cell phone, and tell your family and roommates that you are indisposed for the next, say, hour or two.

-

The Muse likes to be nourished.

Every day, expose yourself to a variety of musical influences — not just the few favorites you keep cycling through. And if you want your Muse to get real exposure to different music, do it with full attention.

-

The Muse likes to be quiet.

Music as a background often silences or distracts the Muse. It is hard to focus on what you are hearing in the mind’s ear when you’re hearing things in your physical ear. The Muse is shy. Silence often causes her to come out of hiding.

-

The Muse needs you to follow where she leads.

The Muse can’t do it all; you have to do your part. Once the Muse gives you something, run with it. Work it, play with it — above all, capture it. Write it down! Never think that you’ll remember what the Muse tells you. No matter how impressive your melody seems at the moment, it will slip out of your head just as magically as it slipped in.

-

The Muse needs you to remember what she says.

Keep a pencil and paper or a simple recording device next to your bed. The first few seconds after you wake up provide the best opportunity to clearly recall your dreams. Discipline yourself to write them down, even if there is no music in them. And when you do wake up with a strangely unfamiliar and uncharacteristic Beatles song in your head, get it down on paper or tape. It is possible that it wasn’t a Beatles song at all, but your muse playing hide-and-seek with you.

(Of course, make sure it wasn’t an actual Beatles song before you try to publish it! This is what happened with Paul McCartney when he wrote “Yesterday” — he woke up with the tune in his head, but it sounded so familiar he couldn’t believe he hadn’t heard it somewhere before. He went around worried, for weeks, asking people if they had heard it before.)

-

The Muse works for you.

If you sit at your keyboard, piano, guitar, computer, or pad and paper long enough in a patient, receptive state, your muse will show up more often than not. The muse lives in your subconscious mind, waiting for only one thing: your impassioned receptivity. Once you figure out how to turn that on, you will be on another level entirely as a composer. If you defend a routine time and place to work quietly, your muse will become trained to know when and where to make an appearance.

-

The Muse is fickle.

Of course, even if you do all of this, it doesn’t always work. That’s why we call her the Muse.

Finding Melody in Your Instrument

Once you have played an instrument for a while, you develop certain unconscious habits that are imbedded in your muscles and nerves. You can turn these habits to your advantage.

Using scales in composition

Playing scales over and over on the piano, for example, trains your hands to behave in a certain way. This hand behavior becomes second nature, and you become better at grabbing the notes of a piece of actual music. In fact, many pieces of music have melodies that are not much more than scales.

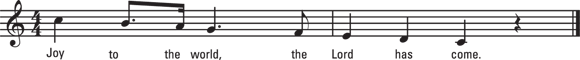

Consider “Joy to the World” (Figure 5-10).

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 5-10: “Joy to the World” uses the entire descending major scale in its melody.

The first eight notes of this incredibly famous piece are just a descending major scale — pretty easy notes to grab even for a novice musician.

So scales can definitely be used as melodies. We would get pretty tired of hearing just scales for melodies after a while, but there are tons of examples of scales, or pieces of them, appearing in melodies.

Any succession of notes that comes naturally from the mechanical skills of a musician can be used for melody. (Of course, ones that don’t come so naturally can be used, too, but that is covered in the next section.)

Each musician has strengths and weaknesses in her playing technique. If you were to get two or three guitar players to improvise freely on the guitar, each of them would bring idiosyncrasies to the task. But because they have certain trained habits, just the act of grabbing a few seemingly random notes has the potential of generating excellent melodic ideas.

On the other hand, many musicians think everything they play is golden. Sometimes it’s hard to evaluate your own work. Criticism is better than praise in this context most of the time. Find someone you can bounce ideas off. If you are receiving constructive criticism, and the criticism makes some sense to you, you are on the right track.

Using music theory in composition

With enough knowledge of music theory and a familiarity with the mechanics and languages of instruments, a composer can invent melodies. These melodies emerge from the possibilities within scales, modes, keys, and the techniques and limitations of the musicians who will be required to play them.

For example, a composer who knows how far a breath can get a musician on a clarinet — and the range of the instrument and its limits in terms of speed and versatility — can write melodies for that instrument largely out of theoretical abstraction. Just throw possibilities and challenges at the instrument based on a mode or mood that you are trying to convey. At one moment, you can create fast-moving, frenetic phrases that jump about like grasshoppers, and at the next, you can conjure pensive, provocative themes to be traded and danced around by the instruments.

This type of melodic composition demands an intimate knowledge of both music theory and the demands of playing each instrument. It can lead to many powerful results, although the composer often doesn’t have such a clear idea of what the result will be until the music is played. It can be hard to hear these things in your head.

Using musical gestures as compositional tools

Many composers use musical gestures to connect themselves to their music, from tapping their foot or clapping their hands while humming the beginning of a tune to writing a piece of music inspired by the movement of people or things around them. The music accompanying dance performances is sometimes written independently of the dance itself — such as Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring” and the resulting ballet performance — while most folk music is written to accompany an existing dance style and follows fairly strict compositional guidelines. Other times, a dance is set against one piece of music, and a composer is brought in to compose new music for the performance by watching the performers and turning their movements into music. In dance performances, music is intended to heighten the sense of joy or tragedy or longing that the choreographer is trying to communicate to the audience without using any words except the movement of the bodies on stage.

Exercises

The following exercises help you practice putting together your own musical phrases and finding the melody for your songs.

-

Keep working with language.

Short or long phrases are rich sources of rhythms and melodies. See if you can fit a couple of different phrases together in a way that makes rhythmic or melodic sense. Take the melody you found in language phrases, and see if you can fit a different phrase into the music. Write the phrase once and then write a variation. Read poetry for inspiration.

-

While listening to a piece of music, draw freely.

Take a crayon, pen, or pencil and freely draw, moving your pencil along with the flow and contours of the music. You can draw abstract shapes, or if you prefer, something the music reminds you of. If you’re using a colored pen or crayon, pay attention to the colors suggested and use them.

- Draw the landscapes suggested by the melodic movements of a piece of music.

-

Come up with a short melody to describe the scene outside your front door.

Add two or three more elements from the scene to it — a car driving by, a dog barking, a squirrel skittering past, the baby across the street screaming — and see how much of the individual parts of the scene you can put together. Your neighborhood has a soundtrack — what is it?

-

Sit quietly with the TV and the radio turned off and listen to your breathing.

Does a rhythm or melody bubble up? Be prepared with paper and pencil. Keep paper and pencil next to your bed. Force yourself to write something down every morning immediately after waking up. Even a single word or a measure of music could help you get in touch with your muse. Have an instrument nearby that is ready to go. Take your guitar out of the case and leave it sitting in a stand, ready to play. If you get a melody in your head, force yourself to write it in the key you heard it in inside your head. This will help keep your material from all sounding the same.

-

Sit at your instrument and just let your hands land on the notes.

If you don’t come up with something good right away, keep repeating the mediocre things until they lead to something better. Trust your hands. If you hear something unusual or dissonant, don’t throw it away — work with it. How will you resolve the ideas?

-

Try writing a few phrases of random notes keeping within a key or mode.

Think of a specific instrument when you write. If it is a wind instrument, remember that the musician needs to breathe. If it is a stringed instrument, keep the bowing and picking in mind. Just fill up some measures without thinking too much about how it might sound. Then try playing what you wrote. Make adjustments where necessary.

Music is a metaphorical language, and language is descriptive by nature. Your job as composer is to describe an emotion through your choice of rhythm and melody — among other things.

Music is a metaphorical language, and language is descriptive by nature. Your job as composer is to describe an emotion through your choice of rhythm and melody — among other things. Learn to be a pack rat. Keep all your ideas.

Learn to be a pack rat. Keep all your ideas.