Napoleon and the Deep South

January 3rd 1985

It was a cold, foggy morning when we landed. I was welcomed into Delhi by a flint-eyed Indian ‘businessman’, lying in wait just outside the airport. He wanted to buy my duty-free cigarettes and whisky. He was followed by six other traders, all wearing the same conspiratorial grins and all wanting exactly the same thing. The incredible prices they were offering sent my eyebrows soaring. I had just been introduced – during my first few minutes on Indian soil – to the country’s thriving black market.

On the airport bus into New Delhi, I met up again with Kevin – the only other Englishman I had seen on my flight. I found him staring out of the bus window at the busy traffic thoroughfare beyond the airport concourse. Suddenly plucked from his sleepy bedsit in Lowestoft and set down on manic Mars, his square, ruddy face wore a look of open-mouthed astonishment. The traffic resembled a stock car rally, with every driver on the road blindfolded.

Everywhere we looked, buses, coaches, auto-rickshaws, taxis and huge public carriers were hurtling down the highway, cutting each other up with total disregard for their (or anyone else’s) safety. There were indeed so many vehicles passing each other on the wrong side of the road that it was almost impossible for us to guess what the right side of the road was.

Kevin’s sense of order and propriety was grievously offended. He hopped off the bus to see what would happen if he tried crossing the road on a nearby zebra crossing. All that happened was that he nearly got run over.

Peering through my round Lennon spectacles, running a contemplative finger over my bearded lips, I wondered what Kevin was doing here. Me, I’d come looking for the ‘spiritual’ India – I had taken up Buddhism recently and wanted to know where it all started. Kevin had no such excuse. If it was a holiday he was after – watching him so rashly dice with death – I didn’t think he’d be getting one.

Teeth gritted, I took in the scene. Every vehicle, large or small, seemed to have a loud horn. And it weaved recklessly in and out of the speeding traffic, blowing its horn again and again. It was apparently the only way it expected to ever get anywhere. The collective effect of all these bus air-horns, car bleepers, rickshaw hooters and bicycle bells screeching and blaring away in competition with each other was absolutely deafening.

Our bus plunged into this chaos without warning. Two passengers having a quiet smoke outside were left behind. A couple of minutes up the road, the driver figured he’d missed a turning somewhere and ground the bus to a halt in the middle of the frantic traffic. Then he reversed it slowly back up the highway, leaning out of his window in search of the lost turning. The Red Sea of speeding vehicles bearing down on us from behind magically parted to permit this terrifying manoeuvre. One auto-rickshaw came so close, I could smell the wheels burning. Its tyres, I noted with astonishment, were not only bald. but the rubber was flapping away in loose strips along the hubcaps.

Kevin calmed his nerves by taking photographs. He managed to take a whole roll of film in just an hour. Mind you, there was a great deal to see: every few seconds we were getting tantalising glimpses of Indian life wholly unfamiliar to our jaded Western eye. Bullocks and camels strolled past, indolent and slow, impervious to the noise of the traffic. Old men and beggars were selling roasted nuts and holy blessings on the pavement. Large families of destitutes were lighting smouldering fires beside open sewers. Ragged women were scraping around in the filth and offal of the gutters for food for the next meal. Cripples and starving children lay helpless on the side of the road, empty-eyed and listless in their despair. Everywhere we looked, people were living on the bottom, bottom line. After a while, Kevin put away the camera.

Despite both coming to India alone, Kevin and I decided to take a room together this first night, at the YMCA hostel in Jai Singh Road. Little did we know it, but this was the start of a great adventure – we would be travelling together for the next two months, and covering the whole length and breadth of India.

It made sense to share accommodation in Delhi, which could be pretty pricey by Indian standards. Our double room cost us Rs135 (£10), but the Y’s facilities for guests were superb. They included two resident travel agencies, where I was able to book a bus tour of Delhi, a traditional dance entertainment for a couple of days ahead, a three-day tour of Rajasthan, and finally, a first-class train berth for Madras for the following week. The latter arrangement was a huge relief. I had heard that queuing up for train reservations in Delhi station itself was the nearest thing to purgatory for the foreign tourist.

The hostel also had a useful currency-exchange desk in the reception area. This saved guests another supposedly awful ordeal: having to change money in regular Indian banks. When, however, I appeared at this desk to make my first purchase of Indian rupees, it was deserted. But just outside the hostel entrance my problem was solved. A horde of unemployed rickshaw drivers rushed up, all wanting to buy my cash dollars on the black market. The exchange rates they offered were at least 20 per cent better than advertised by the hostel. I selected a taxi driver – a red-turbaned Sikh – and he drove me somewhere discreet to make the transaction. As he handed his money over, he warned me that if the police turned up I should be prepared to run in both directions at once.

By now, we were ready to partake of some genuine Indian cooking. Our mouths were watering at the thought of all those delicious curries, tandooris, birianis and assorted relishes for which India is so famous. What we ended up getting, in the YMCA’s gloomy restaurant, was a chicken curry – with no chicken in it. When we complained to the waiter, he fished around in the thin sauce and came up with a single sliver of chicken – about the size of a matchstick – which had been hiding behind a tomato. He gave us a triumphant grin.

Soon after coming into the vast circus of Connaught Place this evening, we attracted the attentions of a small, persistent beggar-girl. Her hair was lank and greasy, her nose was running with snot, and her whole body was painfully thin. She followed us halfway round the square, begging for just one rupee. Or the cost of a cup of coffee. What were we to do? Confronted by a tiny infant, her eyes wide with hunger, her clothes a single torn rag, her grimy little hand stretched out in a desperate plea for money, were we going to give her the price of her only meal of the day? Or were we going to be deterred by the many, many similarly impoverished and starving Indians all around, and simply turn her away?

No sooner had we ‘paid off’ the beggar girl, than we spotted three Indian workers wheeling a massive movie billboard up the road on a creaky old car. ‘SEX AND THE ANIMALS!’ shouted the poster slogan, ‘THE MOST SIGNIFICANT PICTURE EVER MADE!’ Astonished, we followed it down the road to see what was so significant about it. ‘BANISHES MAN’S GUILT AND FEAR ABOUT SEX!’ we read further, ‘ANIMALS HAVE NO SHAME!’ Proving the point, the rest of the billboard was full of tigers, horses and rhinoceroses all coupling away with big grins on their faces. We later learnt that this curious epic was the most popular film playing in India at the time – it was packing them out in every cinema throughout the country.

Stepping back in our amusement, we nearly fell down an open sewer. These gaping holes in the pavement, often full of fetid green excrement, are quite common in the area of Connaught Place. And it is very easy to fall down them, especially in the dark. Parts of this large circus are unbelievably filthy. One particular wall, for instance, ran about a hundred yards round the outermost circle of Connaught Place and had been turned into some sort of public toilet. Long lines of Indians were squatting down by it, as we passed, to relieve themselves.

We walked back to the lodge, through laughing throngs of nut-roasters, bicycle repair men and rickshaw drivers, noticing the beggars beginning to gather together round heaps of old smouldering tyres for warmth. Elsewhere, the many small herds of itinerant cows and bullocks were huddling up together also, mainly on the lawns of the public parks. It was a cold night.

January 4th

During a coach tour of the city this morning, our young Hindu guide suddenly became very excited. ‘Look, there!’ he pulled at my sleeve and pointed. All I could see was a hugely fat Sikh puttering past on a tiny motorbike. ‘You are seeing?’ exclaimed the guide. ‘Is not this man looking healthy?’

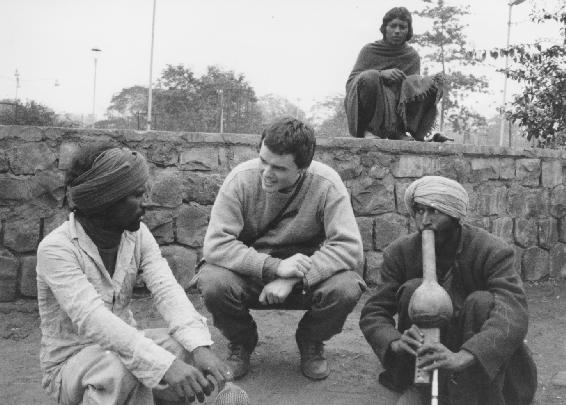

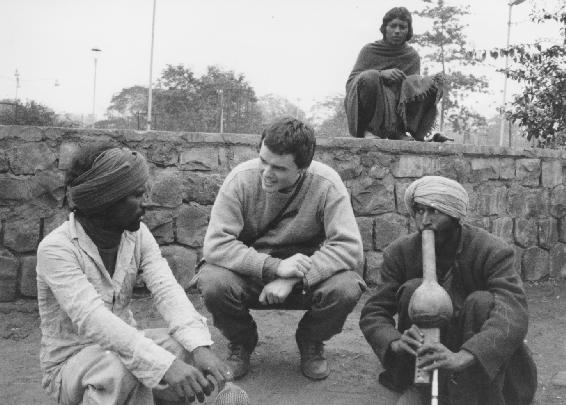

The afternoon tour took us on to Old Delhi, stopping first at Laxmi Narayan Temple. The moment the bus stopped, we were surrounded by beggars, salesmen and traders. They all had just two things to sell – a road-map of India, and a pack of ‘dirty postcards’ which were actually just photos of erotic temple-carvings. To get rid of them, I bought the road-map and Kevin the dirty postcards. This freed us to watch a local snake-charmer trying to coax two sleepy cobras out of a basket. He didn’t have a lot of luck. The snakes didn’t like the cold, and slumped back into the basket moments after showing their faces.

At the back of the Red Fort, our final stop, I came across two young Hindus performing a levitation act. Lying under a large red sheet spread across the ground, they took it in turns to rise up in the air to a height of about twelve feet without any evidence of props. This spot, below the Fort and overlooking the Yamuna River, was apparently famous for local acts – rope-climbers, magicians, conjurers and dancing bears – being performed for the benefit of tourists. The Fort itself was also full of large monkeys. By the entrance of the Lahore Gate, I saw one of these inquisitive creatures assault a fat lady tourist and rob her of a bunch of bananas. Chased up the fortress walls by a fierce turbaned guard, it grinned back down on us from the battlements, a half-banana still jutting from its mouth like a Churchill cigar.

January 5th

This afternoon, we took a rickshaw into the old city of Delhi. We walked the final stretch along a long main road which had been turned into a street bazaar. The pavements were crowded with traders and salesmen selling clothes, books, watches, old boots, umbrellas, even complete sets of dentures. The iron railings by the footway were the province of astrologers, palmists, gurus, holy men, and sex specialists. This bazaar, we had earlier learnt, was also a favourite stamping ground for ‘marriage brokers’ who regarded foreign tourist as highly eligible prizes for their high-born clientele. Many Indian ladies, it seemed, would like nothing better than to marry a rich Englishman or American who would gain them a quick passage out of India. And it would be little use telling the broker you weren’t rich. The very fact that you could afford to visit his country would be conclusive proof of your great wealth.

We cut across a park towards the Jami Masjid, the world’s largest mosque, and were hailed by a succession of half-naked Indian masseurs sitting on rush mats, who were keen to give us a good massage and then to clean out our ears. Another tourist, whom we met later, told us that their services were actually very good.

What was not very good about the old city was its incredible squalor. Coming out of the central bazaar area of Chandni Chowk, we found ourselves in an impossible madhouse of congestion and noise. Adults and children alike were urinating and defecating on the streets, the public urinals having overflowed through overuse. Pitifully disfigured cripples huddled in doorways or in gutters. Scabrous rabid dogs – painfully thin and crawling with fleas – foraged weakly among the heaps of refuse. Cows and goats lay in their own dirt, swarming with flies and maggots. And into all this ploughed an urgent convoy of traffic, cutting a horn-powered swathe of din through the sea of human and animal debris and filth.

The bazaar itself was a full-scale assault on all the senses. The noise was deafening. The stench of rotting fish, vegetables and meat, and the acrid reek of offal, urine and sweat, was overpowering. And what we could see both fascinated and repelled us. In between heaped piles of excrement, legless cripples wheeled themselves about on fruit-box trolleys. On the mud-caked pavements, small swollen-stomached infants were dying of hunger. And everywhere we looked, hundreds of starving eyes followed us, begging money to relieve their misery.

In the middle of a muddy swamp (which used to be a street) appeared the Hotel Relax. ‘Welcome!’ said its filth-splattered sign, ‘Come Make Nice Comfortable Stay With Us!’ The grinning old bandit at the door spat a jet of red paan (betel-nut juice) across the street and beckoned us eagerly inside, his gaze travelling covetously over our possessions. We nodded polite refusal, and continued on our way.

We next came across a flamboyant character mixing up what looked like raspberry-coloured puke in a huge cauldron. He was surrounded by a crowd of attentive Indians, all watching his activity with silent, respectful interest. It turned out to be a cake-making demonstration. We stood and looked on for a while, and then a smartly-dressed young Hindu turned up and said, ‘Hello. You are wanting hashish?’ He made this surprising offer in a loud tone, audible to half the crowd, and in the casual, offhand manner of someone offering a friend a cigarette. Kevin quickly drew me away from the scene. He had heard that many dope-dealers in the old city were in fact police informers.

Both of us returned to the hostel in a state of shock. Kevin, however, soon rallied to show me his surprise import into the country – a parcel containing ninety-two condoms. He then disappeared into town with two Italian schoolgirls, both of whom were devout Catholics and due out on the morning bus back to Rome. Kevin, I was coming to realise, was one of life’s born optimists.

January 6th

This evening, we went to the Parsi Anjuman Hall, near Delhi Gate, to see an entertainment called ‘Dances of India’. We were expecting great things of this, the programme having promised us ‘Seventy-Five Minutes of Glorious Music, Dance and Song in all their Exquisite Finesse.’

When we came into the hall, we were surprised to see only seventeen other people in the audience. They were all shivering and huddled together for warmth, for the hall was very large and there was a gusty draught blowing through it. But then the show started, and everybody quickly forgot their discomfort. The skill and artistry of the dancers, performing many traditional Indian routines, soon held us spellbound with admiration. Particularly good, from our point of view, were the Peacock Dance (advertised as ‘a Peacock in ECSTACY during the MONSOONS’) and the Bhavai (‘the Dancers PERFORM on Sharp Swords, Tumblers and Brass Plates with Seven POTS’). During the Bhavai, one of the dancers slipped on one of her brass plates and sent it spinning off into the wings like a flying saucer. To her great credit, she kept her balance perfectly. The Seven POTS on her head barely trembled.

The auto-rickshaw we took home was little more than a motorcycle with a flimsy passenger canopy bolted over it. The suspension within was non-existent. Kevin and I bounced around inside the carriage like a couple of ricocheting bullets, and arrived back at the hostel with the fillings shaken loose from our teeth. The driver, by contrast, had spent the whole journey calmly leaning out of his cab, curious to see if his front wheel had fallen off yet.

January 7th

I spent this morning in the warm company of Mr Hardyal Sharma, a member of Nichiren Shoshu of India. This small, growing organisation marks the return of true Buddhism to the country of its origin after an absence of several hundred years, since being overshadowed by the Brahman pantheon of Hinduism. Founded by Shakyamuni (Gotama) Buddha some 3000 years ago, and revitalised by Nichiren Daishonin in 13th century Japan, Buddhism in its original, pure form is now again setting down firm roots in India.

I emerged from Mr Sharma’s house in a dense fog, and it took me well over an hour to return to the YMCA. My rickshaw driver, despite his protests to the contrary, had no idea of where he was going. Having failed to persuade me out of the cab at the Nehru Planetarium, on the other side of town, he promptly reversed a mile back up the foggy highway (with no lights on) in an attempt to terrorise me out. He had evidently become tired of patrolling the city in the freezing mist and wanted to go home. Finally, he admitted he was quite lost and began taking directions from pedestrians. The last (of many) he asked told him that he had accidentally parked right outside the YMCA. He gave me a look of triumph, then enquired whether I had any dollars to sell.

Kevin I found in the restaurant, consoling an elderly woman tourist who had just had her bag and all her money stolen. She had only taken her eyes off the bag for a moment. Her story convinced Kevin that he would have to tighten up on his personal security. He presently wore a bulky body-belt – containing his money, travellers’ cheques, airline ticket and passport – round his waist. But the woman had told him that this wasn’t sufficient. Indian pickpockets were used to unzipping waist-belts and removing their contents without the wearer’s knowledge. So Kevin decided he must locate the belt somewhere else on his person.

Back in our room, he stripped off and set to work. The belt began to work its way round his body like some kind of virulent spore. First it appeared round his right thigh, but this was no good. When he tried to walk, it simply slipped down around his ankles. Next, it turned up secured round his crotch. But this left him waddling round the room like a bandy-legged Gandhi. Then it settled round the base of his spine, just below his trouser-belt, but this felt like a truss. So he shifted it up to his chest. Now it looked like a pacemaker, and was strapped so tight he couldn’t breathe. Finally, it came to rest under his left armpit, which was where I wore mine. But the belt was so bulky, that even with a shirt on, he looked grotesquely deformed.

Kevin confessed himself beaten, and returned the money-belt to his waist. To make it safe, however, he tied it to his person with so many pins, clips and padlocks as to foil even the most professional of thieves. The only problem was that Kevin couldn’t access it himself. Later, when he wanted to buy a simple bar of chocolate, he had to enlist the shopkeeper, his assistant and myself to help him break into his own money!

January 8th

Today we set off on our three-day coach tour of Rajasthan, arguably India’s most beautiful state. Breakfast was taken at a sleepy roadside restaurant along the way where bored elephants, moth-eaten camels and drowsy snakes were prodded into action for our benefit, then allowed to go back to sleep again.

Coming first to the Tomb of Akbar at Sikandra, we acquired a curious Indian guide with fond memories of the British Raj. He had a very military bearing, wore a swagger-stick under his arm, and sprinkled every sentence he uttered with quotations from Wordsworth or Shakespeare. His best contribution referred to the hordes of large wise-looking baboons scampering all around us. ‘Attention!’ he barked authoritatively. ‘Many a slip betwixt cup and lip! If bit or scratched by monkey, go running immediate to doctor! Get anti-rabbi jab!’

Arriving next at Agra, the warm sun having now dispersed the chill from the air, we were again surrounded by an insistent troop of salesmen, this time selling cheap plaster models of the Taj Mahal. Nobody was interested. We all wanted to see the real thing. And we were not disappointed. Our first glimpse of this incredible ‘monument to love’ dispelled all our doubts regarding its reputation. The massive white marble structure glittered like a priceless jewel in the bright midday sun, and was equally perfect to my eye whether viewed from afar or right up close. As for the interior, a note of pathos was sounded by the twin tombs of Emperor Shahjahan and his wife Mumtaz. It is said that Shahjahan, prevented from draining the public coffers further by building a tomb of his own (a replica of the Taj, in black marble) and locked up for many years by his son should he attempt it, finally elected to be buried alongside his beloved wife instead.

Proceeding on, I put my camera out of the bus window for a quick snap of the street bazaars. To my surprise, the whole street ground to a halt. Every Indian in sight stopped whatever he or she was doing, and posed for the camera. Then, the shot taken, they instantly resumed their busy, noisy activity. Later, coming out of the magnificent ‘ghost city’ of Fatehpur Sikri (deserted by its vast population after just 17 years, when the water-wells ran dry), another odd incident occurred. A young boy came up to offer me a charming marble statue in return for my socks. I padded back to the bus in my bare feet.

At our lodgings that evening, the Bharatpur Tourist Bungalow, we all crowded round the restaurant’s single one-bar heater and anxiously waited for some hot food to warm us up. The night was becoming increasingly cold. A breakfast menu appeared on our table, and I studied it. We were given a choice of PORDGE and CORN-FLEX, followed by BED TEA. Then there was SAND WITCHES, to be followed by MANGO FOUL and CARAMEL CUSTERED.

Finally, the waiter appeared and asked us what we would like. We returned the menu and told him, but he didn’t have any of it. He just waggled his head sorrowfully and said to everybody, ‘So sorry, this is not possible.’ He couldn’t tell us why it was not possible, just that it wasn’t. We couldn’t understand it. Then Kevin said, ‘Look, forget about what we want. What have you got?’ That did the trick. The waiter nodded furiously and replied, ‘Meals!’

In India, ‘meals’ are often another name for thalis. Our thalis arrived on large metal platters, and comprised a large heap of plain rice (cold) in the centre, surrounded by five small dishes of curried vegetables, chillies and curd. Most of us, unused to such food, gave the ‘meals’ a miss and sucked listlessly on our chapatis instead. Only one of our number, a ruddy-faced Australian, finished his food completely. He couldn’t speak highly enough of thalis. He assured us that we would all get used to them in time. Kevin looked at him as if he was crazy.

January 9th

Dawn saw us trudging down to the Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary in the freezing fog. Our guide told us that this was the best time of day to view the rare and exotic birds, but none of us could see anything. There was only one bird enthusiast in our party, a myopic Indian who stalked the guide relentlessly in his hope of seeing some rare snipe or giant crane. This hope dashed by the thick mist over the marshy lake-land, he settled for going duck-spotting. ‘Ah, over there!’ he would declare at regular intervals. ‘Dat is a mallarrrrd!’ And the guide would nod at him indulgently, even when (and this was often) it wasn’t a mallard at all.

‘Excuse me,’ asked Kevin over breakfast, ‘but where does your milk come from?’ The waiter stared at the thick brown scum of oily globules floating on Kevin’s coffee, and replied: ‘Baboon.’

Relaxing this afternoon on the lush green lawns of Sariska Tourist Bungalow, I watched all the others leave on a bus to the nearby nature reserve. They all wanted to see Sariska’s famous White Tiger. Hours later, they returned tired and disillusioned. They hadn’t seen anything at all, let alone the White Tiger. The bus had roared through the reserve at such speed that every animal they passed had instantly scurried for cover. All that Kevin had seen was a couple of wild pigs (who tried to head butt the bus), a rhinoceros (asleep) and a peacock (dead). The bus had finally screeched to a halt at a Monkey Temple, where the guide told everybody to go in, dong a big bell, and pray to the Monkey God for the White Tiger to appear. But nothing happened. Later on, we discovered that the last White Tiger seen in these parts had been captured years ago, and was now a stuffed exhibit in a Delhi museum.

Over supper, I met a statuesque Australian girl called Anna, who had just wasted the last two months waiting in Tibet for the Dalai Lama to show up. She said he was as difficult to see as the White Tiger. Then she introduced her ‘companion’, a small Indian man to whom she was trying to teach English. On parting, he kindly offered to show me a ‘good time’ when we next met. Corrected on his poor phrasing by Anna, he apologised and said, ‘So sorry! I mean I enjoy you next time!’

I was joined in the cold, empty drinks lounge later by the reception clerk. He was a swarthy, grinning man with bad teeth. After telling me all about his crippled grandmother, his suffering wife and his hungry children, he offered me a hashish cigarette. Then he snuggled up close, and offered me a share of his blanket. Nervous, I went off to my room. He tried to follow me in, but the sound of Kevin’s loud snores within managed to deter him. I came to my bed tired, but was unable to sleep. Outside my window, what sounded like a hundred cats were yowling away in unearthly chorus. In the morning, I found out they hadn’t been cats at all, but peacocks.

January 10th

Our bus driver excelled himself this morning. In the course of his usual game of ‘dare’ with speeding buses coming the other way, he managed to nudge a camel and cart down a deep ditch. All the Indian tourists aboard thought this highly amusing, and shouted up hearty congratulations.

The first stop today was the Amber Palace, near Jaipur. Set atop a high hill, this magnificent structure glowed like a bright yellow pearl against an impressive backdrop of rugged hillside watchtowers and fortifications. Walking up, we came through a small garden seething with giant rats. A couple of New Zealanders with us explained that the rat (and the peacock) were worshipped as animal divinities in Rajasthan. They recalled a visit to the famous Rat Temple in Bikaner, where the priests hadn’t let them in until they had taken off their shoes. Consequently, when they had entered the temple courtyard, scores of wild rats began scuttling over their bare feet and running up their trouserlegs.

On the way home to Delhi, we stopped at a ‘halfway house’ tea-shop which had been set up by the Rajasthan Tourist Board to encourage tourism. I patiently waited through the tea queue, but was sent away to buy a ‘tea coupon’. So I patiently waited through the tea coupon queue, but then found the coupon man had gone for his own tea. I patiently waited for him to return, and then he gave me a marmalade toast coupon by mistake. So I had to come back and start queuing all over again. Then the coupon man couldn’t give me a tea coupon, because all I had was a torn two-rupee note which he couldn’t change. Kevin finally lent me the money, and I got the tea coupon. The glorious words ‘One tea!’ floated back to the kitchen, and I thought I was in business. But then there was a power-cut, and when the lights came back on the tea-man had lost my coupon and I had to queue up for another one. By this time, the bus was impatiently hooting for our return and I had to forget the whole thing.

January 11th

Visiting the Odeon cinema in Connaught Place, we caught the 10am matinee showing of The Blue Lagoon in English. The audience turned out to be just as interesting as the film. Mostly Indian men in their 20s and 30s, they took a strangely lascivious delight in this innocent story of two children growing up and falling in love on a desert island. We knew that in their own films, hero and heroine were not allowed to even kiss on-screen, but the attention these two scantily-clad children received whenever they embraced or revealed bare flesh was amazing. The audience were quite beside themselves with suppressed excitement, and giggled and pointed throughout the picture. Then, just five minutes from the end - with the children being rescued and set to recover some clothing – everyone rose in unison and made a noisy exit from the cinema. When the lights came on, Kevin and I found ourselves in an empty auditorium. Well, not quite empty – there was an usher present. But he was lying fast asleep over the rear seats.

This evening, Kevin tried phoning a girl he had met on the Rajasthan tour. But he couldn’t get through. He spent two long hours at the phone, and ended up having a strange conversation with a cake-shop owner in Connaught Place.

Some people do manage to use India’s internal phone system successfully though. We’d heard someone having a very successful phone call at 5 o’clock this morning. It was an Indian guest using the public phone on our floor. He was shouting down the receiver so loudly that everybody on our corridor woke up. Each time he came to the end of a sentence, he uttered a booming ‘HA, HA, HA!’ Which made us wonder why he needed a phone at all.

January 12th

We moved out of the YMCA at noon today, and went in search of a Hindi film to pass the time while we waited for tonight’s train down to Madras. Most cinemas we came to had the ‘House Full’ sign up, and were fully booked three days ahead. We began to realise the enormous popularity movies had in India. Then we came to one cinema, the Plaza, where tickets still remained. We joined a long queue of Indian men, none of whom knew what they were queuing up for. We questioned many of them, but nobody we asked knew the title of the film, what it was about, or even what time it started.

This was the first Hindi picture either of us had ever seen, and it was really rather good. It depicted the lives of three Indian women from varying castes and social backgrounds, and described the ways in which they inter-related. The first of the women was very rich, very bored and slept a lot. The second went out to work, was married to an alcoholic husband, and suffered constant abuse from a mother-in-law. The third was a lowly servant, afflicted by the continual bad moods and childish petulance of the other two. It was all very interesting, but we couldn’t help thinking what a difficult place India must be for women, no matter what their background.

We reached New Delhi station at 6.30pm, and boarded the Grand Trunk Express bound for Madras. In view of the very lengthy (thirty-six hours) nature of this journey, we had decided to travel First Class, in air-conditioned sleeper berths. This was a mistake. We should have taken the Chair Car accommodation, but it was too late to think of that. We found ourselves in a carriage full of boisterous Indian athletes, all singing rock and roll songs. If this was not enough, we found our berths to be a simple six-by-three bare plank apiece. The prospect of lying on this for the next day and a half was daunting. To console himself, Kevin ordered some train food. It turned out to be yet another thali, and he disconsolately threw it out of the window. Our Indian friends ceased singing at 10.30pm, and the lights went out. Then, just as I was asleep, one of them began having a loud nightmare and I woke up again. It was to be a long, long night.

January 13th

The morning began with all the Indian athletes bellowing morning greetings across to each other from their bunks. Caught in the crossfire, we woke up. Kevin went for a stroll, and returned to tell me that we had been stuck in Vidisha station the past two hours, owing to a train being derailed further up the line. And a further three-hour delay was expected.

Leaning out of our window, we spotted a wizened old cha-wallah beetling up and down the platform, carrying a large aluminium teapot and a box full of earthenware teacups. As we waved and tried to gain his attention, a hail of these disposable teacups – their contents finished – began to rain down on the platform. The little old man dodged this continual flak of missiles, and picked his way through the broken crockery to serve us our teas with an air of resigned stoicism.

News of our further delay had now swept through the train. Every Indian aboard promptly swarmed onto the platform to clean their teeth. There were about six enamel double-sinks along the platform, and each one was soon surrounded by a jostling crowd of Indians brandishing their toothbrushes.

Eventually, the train moved off. Then it stopped again. Then it started, and stopped and started. By noon, we were running five hours late. Passing through Bhopal, the weather was becoming noticeably warmer, and as we pushed on southward the heat continued to gain in strength. Between Itarsi and Betel, the guard shut all the doors to the train. He informed us that this stretch was notorious for bandit-attacks on passing trains.

It was otherwise an uneventful journey. We ate a freshly cooked omelette on Nagpur platform, and very little else. Most of the time, we just played cards with the Indian athletes, or lay for hours on end on our tiny bunks, imagining the walls closing in on us. We wondered if this journey would ever end.

January 14th

I’d changed my mind. The nearest thing to purgatory for the tourist in this country was not waiting in an endless train reservation queue. It was lying endlessly in a tiny coffin-bunk in a so-called express train now running six hours late. I woke up feeling I had been on this train all my life. My whole world had shrunk to a cramped compartment six feet square. Apart from the occasional cigarette break on a station platform, the outside world might as well never have existed.

Our Indian fellow-passengers livened things up for a while by teaching us how to eat thalis. They had caught Kevin trying to throw another thali out of the window, and forced him to try eating it the ‘Indian’ way. This involved Kevin mixing all the rice, curried vegetables, chillies and peppers together in a big steaming heap of yellow mush, and then stuffing it down his throat in large dripping handfuls, muttering the while that he couldn’t remember ever having eaten anything so tasty.

We arrived in Madras forty-one claustrophobic hours after leaving Delhi. It was noon, and the heat was intense. We stumbled off the train feeling like two convicts unexpectedly reprieved from Alcatraz. Kevin’s face, I observed, was deathly pale. He looked like Lazarus recently recalled from the grave.

Madras station was a nightmare of noise, heat and unpleasant smells. We struggled quickly out, and went in search of quiet, clean lodgings. All we managed to find – it being a festival day and most places being full or closed – was the AVC Hotel in JB Street. This place was cheap but was obviously not used to Western tourists. Our room-boy, a burn-black Indian wearing a lunghi (sarong) and a permanent grin, was so fascinated with us that he followed us into our quarters and stayed there. Kevin temporarily shifted him by ordering a cup of black coffee, without sugar. The room-boy presently returned with a cup of white tea, with sugar. He beamed happily at Kevin, and Kevin glared banefully back. It was the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

The room-boy was particularly fascinated by my dirty laundry, which had just been unpacked. He couldn’t keep his eyes off it. I concluded that he must be the dhobi-wallah eager to wash it, so I stuffed the lot in his arms and said ‘Please do dhobi.’ His response was quite extraordinary. Giving a groan of emotion, he sank to his knees to kiss my feet, then retreated out of the room muttering ‘Presentation! Presentation!’ to himself. Kevin informed me that I just made a present of all my clothes to the room-boy. He was prepared to bet I would never see them again.

I saw the room-boy again though, and only minutes later. After Kevin had retired to his room, I shut my door and collapsed on my bed, pleased to be quite alone for once. But then I looked up at the ceiling, and found that I wasn’t alone at all. There was a yellow lizard staring down at me. We gazed at each other for a while, and then I got bored of waiting for it to drop on my head, and called back the room-boy to get rid of it. He came in waving a broom and proceeded to chase the lizard all over the room. Then he opened the door to let it out, and instead let another one in. I now had two yellow lizards.

Later, Kevin and I went out for some lunch, and found a good Chinese restaurant set back from Mount Road. On the entrance door, a curious sign announced:

‘We have been in this Business since long, and we have been pleasing and displeasing our customers ever since. We have been bawled out, bailed up, held up and held down, cussed and discussed, recommended and boycotted, talked to and about, burned up and burned out etc. The only reason we continue to stay in business is to see what in hell could possibly happen next!’

Eating our meal on the pleasant upper-storey, open-air verandah, we noticed many large black rooks flying in and out to dine on leftovers off the dining tables. Kevin observed them hopping his way, and polished off every scrap of food on his plate. He wasn’t going to leave them anything.

Back at the lodge, the companionable room-boy turned up again, this time to beg my best shirt off my back. I only got rid of him by taking him by the shoulders and steering him bodily out of my room. He sat outside the door and went to sleep. Except for the lizards, I was now alone. But I was feeling very hot, and decided to turn on the overhead air-fan. This was a serious error. It had only one speed – very fast indeed. Within seconds, it was whizzing round like an aeroplane propeller. A hurricane blast of air blew me off my feet and pinned me to the bed. The yellow lizard on the ceiling was plucked off its perch and sent flying across the room. Struggling up and turning the fan off again, I found the lizard lying stunned on the floor of the squat toilet. It remained in a state of concussion for the rest of the afternoon.

This evening’s stroll produced a visit to a local Hindu temple, hidden down the end of a dark, narrow backstreet. An elderly priest wearing the marks of Vishnu (vertical lines of red and white paint) on his forehead showed us around. As he proudly opened up all the shrines for viewing, he told us that today was a big festival day, and this was why all the god-figures wore garlands of flowers around their necks.

On the way out, the old man bowed to us and we bowed back. Then he felt compelled to bow again, and so we felt obliged to give another bow. This went on for some time, the three of us bobbing up and down on the temple steps, until the priest broke the monotony by suddenly darting off to get us a ‘present’. This turned out to be a bowlful of very bitter berries which we had to eat in front of him with every appearance of delight. Downing several cups of tea later on, we decided not to take any more ‘presents’ from anybody for the time being.

January 15th

A toothless old man in a dirty dhoti turned up at 8am, armed with a broom and a bucket. He wanted to clean out the squat toilet. First he removed the concussed lizard and then, when my back was turned, he removed a pack of my disposable razors.

Another old man, this time a rickshaw driver cycling us up to Madras station, proved so feeble that we had to get out at every hill and give him a push up. By the time we creaked into the station, he looked so ruined that Kevin was all for calling out an ambulance.

The whole population of Madras seemed to be out on the streets today, celebrating the Spring Harvest Festival called ‘Pongol’. Many people we saw were either waving bunches of bananas about in the air, or carefully painting the horns of sacred cows. They were painting them every colour of the rainbow – one poor beast we saw had one horn daubed bright purple, and the other green and red with blue polka-dots. As we watched, a crowd of noisy children stuck a large lemon and a bunch of lighted faggots on the painted horns, and began chasing the smouldering cow down the road shouting what sounded to us like “bugger! bugger!” after it as they gave gleeful pursuit.

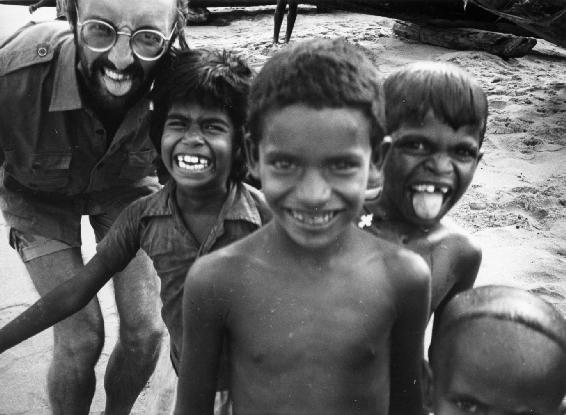

Later, we walked down to the coastline and went swimming off Elliot’s Beach. The sea here was warm, clear and refreshing, and the huge waves sweeping into land shocked us instantly out of our heat lethargy, and left our skin all a tingle. Back on the beach and drying off, we were surrounded by a crowd of curious locals. They appeared to be waiting for something. Moments later, the tide suddenly came in and we were deluged by a large wave. The waiting crowd erupted into loud laughter.

Wandering damply back to town, we came across another decorated cow. This one wore garlands of yellow flowers on its horns and had little brass bells tied round its forelegs. It was contentedly eating a pile of refuse in the gutter. We stepped round it and a local cha-shop. It was occupied by a boisterous gang of Muslim youths who insisted on buying us endless cups of very sweet tea. Kevin tried to protest that he didn’t like sugar, but they didn’t believe him. Everybody in India liked sugar, they said, and lots of it.

Our new friends wanted to hear everything we knew about English cricket and British motorbikes. But neither of us knew anything about either subject, so it was a very short conversation. Undeterred, the inquisitive party moved on to the subject of marriage. They couldn’t believe we were still unmarried. There was so much opportunity to get married in the West. Surely, they insisted, we could afford it?

Madras, we concluded by the end of today’s tour, is a strange city. The Indians here stop and stare at you all the time, and often follow you down the street. Tiny children pass by riding adult bicycles bigger than they are. Entire families of four or five people putter along on single 50cc mopeds. Herds of goats tied together with string wander aimlessly round in the middle of the traffic. Holy cows are allowed to graze and defecate on the lawns of plush banks and hotels. And groups of destitute women and children sleep in carts, on car bonnets, or simply in the gutters. The contrast between affluence and poverty, with lines of beggars sitting outside the best hotels, is in this city extremely marked.

January 16th

We decided to look for better lodgings today. But this was easier said than done. The room-boy, as expected, refused to return my laundry. So I had to refuse to pay the bill. The laundry promptly reappeared, minus a pair of red underpants. The room-boy had taken a particular shine to these. Nothing I said could persuade him to part with them.

After a long search, we found good rooms at the YMCA hostel in Pycrofts Road. My quarters here were clean and comfortable, and there wasn’t a lizard in sight. I did have problems with the air-fan again, though. This one didn’t work at all.

I went down to the rickshaw-rank to get a ride further down Pycrofts Road to the house of another Buddhist contact, Venkat Sai. None of the six rickshaw drivers I asked knew where Pycrofts Road was, even though they were sitting in it. Then a doddering old greybeard creaked up and faithfully promised he knew the way. He promptly swung off Pycrofts Road and got himself thoroughly lost. Then he took a lot of directions from passers-by, and got himself thoroughly confused. But all this didn’t deter him, just made him more resolute. He peddled off into the great unknown with such sense of clear purpose that I didn’t dare accuse him of not knowing where he was going. An hour later however, and having arrived right back where we’d started, I changed my mind. I got out of the rickshaw, thanked him for his guided tour of the city, and walked to my destination.

In the afternoon, Kevin and I decided to change some money at the Indian Overseas Bank. We sat at a desk marked ‘travellers cheques’ and waited for ten minutes. Then someone came over to tell us that this desk didn’t deal with travellers’ cheques at all. He showed us to another desk. This one didn’t have a sign saying ‘travellers cheques’, so we guessed we must be in business. We handed our passports to the desk-clerk, and he stared down at them. That’s all he did, just stared at them. Five tense minutes ticked past. Then he stopped staring at them, and gave them to another official to stare at. Both men wore such looks of intense concentration that we wondered if they’d ever seen a British passport before. The second official, suddenly aware of Kevin’s teeth grinding with frustration, emerged from his trance and returned the passports to the first official, who gave a short grunt and pushed a large heap of forms over to us to fill out. All we got for wading through this lot was a small brass token each. Kevin’s bore the number 22, and mine 29. The indicator panel above the paydesk, we noted with dismay, had just clicked to the number 49. By the time it had worked its way up to 100, and then gone from zero to our numbers, the rest of the day would be gone.

But then the indicator clicked again. It moved straight from 49 to Kevin’s number. Relieved, we collected our money, and asked for a receipt. But the paydesk didn’t issue receipts. It told us to go back to our friends with the fixation on passports, to get one. And surprise, surprise, both officials had just gone for lunch.

January 18th

Something will have to be done about these mosquitoes. Sleep was quite impossible last night. Persistent squadrons of these little bloodsuckers were diving down on me till 4 in the morning. In the end, I shut all doors and windows (ignoring the stifling heat) and lit up three ‘Tortoise’ mosquito-repellent coils. The packet promised they would drive the little monsters into a ‘deep swoon’. An hour later, with room enveloped in a dense blanket of smoke, it didn’t matter whether the mosquitoes swooned or not. They couldn’t even find me! Comforted by this thought, I finally swooned myself.

Lack of sleep made this a difficult day. Apart from which, this was a Friday and all Madras’s sightseeing spots were closed. The only place open, we were informed, was Fort St George. But when we arrived there, this was closed too. We sat on an anthill and drank an insipid cup of coffee. Then we found one place not closed – the charming 18th century St Mary’s Church. This attractive structure had stone flooring tiled with gravestones, marvellous pillar-work and mosaic–patterned ceilings. The only thing that disturbed us was all the signs prophesying a nuclear war.

The enervating heat diminished Kevin’s conversation to a minimum today. He restricted himself to two phrases only: ‘Why isn’t your meter working?’ (addressed to taxi-drivers), and ‘Has that water been boiled?’ (addressed to waiters fond of drawing table-water from next to open sewers). Otherwise, he was quite silent. Kevin had become tired of remonstrating with legions of beggars. Now he simply walked through them. Or, if necessary, over them. They seemed to respect that.

This evening we saw a quack doctor selling health cures on the street. First he used a loud football klaxon to attract a crowd, then he seized a ‘volunteer’ from the audience and held him captive with a pair of prison manacles while he poured a bottle of health tonic down his throat.

Moving on, we came across another crowd, this time piled into the entrance of a television shop. Everybody was pressed against the window watching a television set – something few of them would ever possess – being demonstrated to a customer. On the screen, a fat middle-aged Indian in incredibly tight trousers was rolling up a ski-slope backwards, singing a number one pop ballad. The massed crowds standing outside wore a uniform look of awed appreciation. They had never seen anything like it. Neither had we.

January 19th

We left the heat and chaos of Madras this morning, and travelled down to the peaceful coastal haven of Mahabilapuram. A rickshaw driver turned up at the bus depot, and offered us lodgings in his own house. We ended up with a small bare stone cell in an adjoining thatched hut. The cost was remarkably low – just three rupees (20 pence) each per night. Our ‘neighbours’ were a young couple called John and Suki, who had lived in India some years and who had gone quite ethnic in their dress. John, a dreamy loquacious individual, wore a small fez glistening with semi-precious stones, long flowing robes and a number of exotic beads and necklace. Suki was decked out in a bright ruby-red sari and had applied a thick layer of kohl to her eyes and cheekbones. As we arrived, she was playing a local folk song to her baby daughter, Kali, on an antique squeezebox.

John’s milky blue eyes glistened with emotion as he learnt that Kevin was from Suffolk, only a few miles from his own home town in England. He squatted outside our hut like a mischievous pixie and plied Kevin with an endless stream of questions about life back home. Meanwhile, I had finally located the switch to our single light-bulb, and had noticed that our cell had no furniture in it. Not even a bed. But that was okay, said John, for everyone here slept on the porch outside. It was so much cooler.

Kevin and I went up a winding dirt-track leading up to the beach. Across our path scurried a number of small, grunting pigs, while tiny green frogs leapt in and out of discarded coconut shells. Thirsty dogs lay in doorways, tongues lolling out with the heat. Naked children ran past, rolling old bicycle tyres and cheerfully laughing. Householders sat on their porches, giving us a lazy wave of welcome. The sun shone brightly, and a warm sea-breeze caressed our necks and shoulders. Yes, Mahabilapuram was going to suit us fine.

Up this road, we discovered the Village Restaurant. Not only did it have a good selection of Western music, but both its waiters could speak good English. One of them produced a giant lobster on a plate, and offered it to Kevin. The lobster snapped hopefully at Kevin’s nose, but he didn’t want it. So the waiter stuck it by the entrance, hoping that some hungry passer-by might spot it. The lobster sat obediently on its plate and waved its powerful purple claws about in enthusiastic welcome to prospective customers. But nobody accepted the invitation, and it presently sank into a dejected sulk. To wake it up again, the waiter came over and began plucking its eyeballs. The lobster promptly returned from the dead.

Coming out onto Mahabilapuram’s glorious beach, we spotted its famous Shore Temple. The guide we hired told us that this was the last of seven original sea-temples built by the Dravidian architects of the 7th century AD. The other six had already been consumed by the hungry sea, and this one would soon experience the same fate. Its only protection was a buttress-wall of large boulders, already much weakened by the continuous battering of incoming breakers.

Undeterred by the news that the previous occupant of our hut (a young American girl) had drowned here last week, we plunged into the sea and found it excellent for swimming. Even Kevin, not generally fond of the water, enjoyed romping around in these waves. They helped him forget about the thirty-six mosquito bites on his left arm.

It was impossible to be alone for long on this beach, though. Kevin managed to lose a grinning fisherman trying to sell him a brace of snapping lobsters by claiming to be vegetarian, but he hit real problems with his next visitor. This was a gap-toothed, shifty-eyed pirate –wearing just a ragged bandana and a soiled lunghi – who sat behind us for a whole hour, banging two coconuts together. You can’t imagine what the sound of two coconuts being banged together does to your nerves after a while. The grinning rogue selling them did, though. And when Kevin at last gave in, he uttered a shrill cackle of triumph and began beheading the green coconuts with a razor-sharp machete. The milk within was unpalatably sweet, but the two rupees apiece we had paid was a small price to get rid of the noise.

After an excellent supper at the Village Restaurant – which this evening was crowded with long-stay travellers and hippies dressed in colourful kaftans, baggy silk trousers and patterned waistcoats – we walked around the sleepy village’s only two main streets. All the local Indians here were either chipping away on stone sculptures for tourist sale, or coming up to ask us: ‘You have English coins for my collection?’

We returned to the seashore to view the sea-temple by night. Except for the regular wash of the waves, it was completely quiet. The temple glowed luminous-white in the reflected light of the rising moon. The sky was clear as a bell, and a fresh, clean breeze was blowing in from the sea. We sat on the temple steps, and began to feel the calm, tranquil atmosphere stealing over us and soothing our souls.

Suddenly, a strident voice broke the silence. ‘Gidday!’ it said. ‘Where’s the action?’

The voice belonged to a lively, lanky Australian called Gill, who had brought his English friend Jim out for a night stroll.

‘I’ve brought this whingeing Pom for a glim of the temple!’ explained Gill. ‘He absolutely hates temples. I’ve dragged him round every temple in South India!’

Then he began complaining about the lack of action again, and dragged us all off to a tea-stall in town where he reckoned ‘it all happens’ on a Saturday night.

Once at the tea-stall, Gill leapt forward to exclaim: ‘Okay, where’s the dancing girls?’ The old crone manning the tea-urn gazed at him in mute incomprehension. As well she might, for there were no dancing girls, there was no ‘action’, there was nothing happening here at all. Apart, that is, for six huddled Indians drinking tea and a local cow trying to climb under a low tea table.

Gill entertained us with stories of his visit to Goa. Most of the outside toilets in Goa, he informed us, had pig farms built below them. On his first trip to one of these, Gill got a nasty shock. He’d just squatted down to lower his backside over the hole in the floor (the toilet), when a low, hungry snort below him made him look between his legs. He saw a pair of beady, piggy eyes eagerly waiting for him to supply breakfast.

‘They just love foreign shit, those pigs do!’ recalled Gill. ‘They don’t move an inch when an Indian goes for a crap, but when they see a tourist coming, they’re up and off and forming a queue under that toilet with their napkins on before he’s even crossed the street!’

Kevin and I slept tonight on the porch outside our hut, sharing a tiny mattress lent us by the landlord. It provided very little padding against the bare stone floor. And for a while at least, we were busily occupied fending off invasions of ants, beetles, cockroaches and hopping frogs – all coming from the banana plantation in the nearby garden. For once, however, there were no mosquitoes.

January 2lst

We arrived at the Village Restaurant this morning before the staff had woken up. Whilst waiting for them to get dressed, we discovered the establishment’s beautiful back garden and took turns lying in its hammock, watching the world go by.

The view from the hammock was marvellous – an inland lake, calm and serene; rustic cottages and reed huts dotting the far bank; rows of lush green palm trees and banks of reeds all around, rustling gently in the cool morning breeze.

The whole day followed suit, tranquil and quiet. Even the waves pounding into the shore seemed somehow less angry, less tempestuous. We lay on the beach and did nothing at all. I remarked to Kevin that we couldn’t afford to stay in Mahabilapuram long. It was so pleasant, we might never leave.

January 22nd

The mosquitoes arrived last night. Having remembered to put on ‘Odomos’ repellent, I woke up refreshed. But Kevin and our new neighbour, Nick, didn’t wake up refreshed at all. They had both been plagued by the little vampires all night. The rest of the day, their covetous, envious eyes followed me everywhere, mentally appropriating my small tube of protective cream.

Over breakfast, tears came to Kevin’s eyes as he fought the temptation to scratch his numerous bites. He knew that if he started, he would end up flaying himself alive. So he sweated things out in moody, monastic silence until the irritation drove him out to the garden hammock, where he swung back and forth in restless bad spirits.

Sometimes I don’t credit Kevin. I mean, it’s one thing to stroll around unprotected like a walking lunch for mosquitoes. But it’s quite another to lie around all day unprotected against the fierce sun, stubbornly refusing to use any cream or oil. He returned to the hut tonight looking like a large red blister. I had never seen such a bad case of sunburn. But I had to hand it to Kevin. He has such a remarkable facility for laughing at vicissitude. His entire body burned raw-red and pocked with livid mosquito scars, he told me he was now coming down with flu into the bargain. But did all this deflate him? None of it. ‘You know something?’ he remarked over supper. ‘I don’t believe I’ve ever felt better in my life!’

The conversation came back to the subject of Goa.

‘One guy I knew,’ recalled John, ‘got the dysentery real bad in Goa. A doctor gave him an opium tablet to stick up his backside. But he’d no sooner done this than he got another attack and shot out to the squat-toilet. Well, of course there was this pig waiting down below, and it ate everything that came down – including the opium tablet. An hour of so later, the pig’s owners found it lying on its back in the high street of Goa, kicking its little legs in the air and snorting fit to burst. ‘Man,’ declared my friend, ‘that’s about the happiest-looking pig I ever saw!’

January 23rd

I woke suddenly in the dead of night, surrounded by smoke. I had set my mattress on fire. It had been ignited by the ‘Tortoise’ ring I had lit by my head to keep the mosquitoes away. It took two water-bottles to douse the fire completely, yet the damage was done. I was now left with two problems – how to explain to the landlord the charred lump missing out of his personal mattress, and where to sleep tonight, for the surviving section of it was now a waterlogged ruin. I decided to go for a walk.

It was 3am when I ambled up to the sea-temple. The moon was down, and it was pitch-black. For a while, it was easy to imagine myself the last person on Earth. But then, out of a dark recess of the temple ruins, came a voice. ‘Master!...Rajah!’ it hissed, ‘...you have cigarette?’

The mattress was only slightly damp by the time I returned, so I got some sleep after all. The landlord was not at all pleased when the burnt, sodden bedding came to his attention later on. He did an angry little jig on the forecourt, shouting, ‘Look! Firing! Firing!’ My apologies fell on deaf ears; he was quite inconsolable.

The Village Restaurant was absolutely packed tonight. Kevin had told everybody he’d met that this was the only place in town to get a decent cup of coffee. But the restaurant just wasn’t geared to handle 29 customers at once. The staff simply couldn’t cope. The young waiter, Charlie – normally so cool, calm and collected – was reduced to tears by the continual barrage of food orders. Imbal, a young Israeli girl we’d met earlier, sent me into the cookhouse to see what had happened to the lime lassi she’d ordered two hours previously. I found the cook spread senseless over the utensils cupboard; the pressure of work had driven him to drink. He had been trying to cook 29 suppers on two small electric hot-plates! On the way out, I found Imbal’s lime lassi. Charlie had made it an hour and half ago, but had forgotten to bring it in.

Fed up with waiting, Kevin had been consulting the rest of the guests. He called Charlie over, and told him we had all changed our orders to make things simpler. All he had to do now, said Kevin, was dish up 29 fresh boiled lobsters. Charlie looked at him aghast, and closed the restaurant.

January 24th

We reluctantly left Mahabilapuram today, and took a bus on to Kanchipuram.

There, we found lodgings at the Raja Lodge, close to the bus-stand, and went in search of food. Having had enough of thalis by now, we were looking for the only place in town reputed to have something different – the New Madras Hotel.

Along the way, we took stock of Kanchipuram itself. It was without doubt the noisiest Indian centre we had visited. Its busy streets were full of giant public carriers, the constant blast of their air-horns jangling our nerves and setting our teeth on edge. The air-horns were even left on when the vehicles were parked. As for the many shops and stores along the streets, these were either constructed from planks of uneven timber or from uneven sheets of corrugated tin. The place gave the general impression of a struggling shanty-town – heaving both with people and sacred cows. I had never seen so many cows packed into one place.

It took us a long hour to track down the New Madras Hotel. It should have taken us just ten minutes. None of the locals spoke any English. They did their best – every few steps a grinning Indian turned up to offer us a rickshaw ride or to give us some wrong directions – but we kept ending up back at the Raja Lodge. It was uncanny. And when we did come to the New Madras Hotel, it was a sheer fluke.

The restaurant was something of a disappointment. It had a rather dirty, greasy, seedy atmosphere. But it certainly had some character too. I had just received my egg biriani and stuffed paratha (spelt ‘stuffed parrot’ on the menu), when Kevin discovered a rat under his chair. He promptly leapt up and started a jig of alarm on the table. A party of Indians at the adjacent table, guessing that he was treating them to an impromptu English dance display, began stamping their feet and cheering him on with claps and whistles. By this time, the rat had disappeared. So had Kevin’s dinner. He had sent it flying when he’d jumped on the table.

January 25th

We were awoken in the morning by the Indian party occupying the rooms all around us shouting good morning to each other across the corridor. This racket commenced at 5am. These were the same Indians who had been shouting good night to each other until 12 the previous night. We wondered how they managed on just five hours sleep. We also wondered why they felt obliged to impose the same ascetic regime on poor, weary travellers like ourselves.

The morning’s breakfast – a cup of coffee and a bun – was taken at a roadside cha-house. We sat on a low wooden bench, our feet covered in a black moving carpet of flies emerging from the nearby gutters. It was decided to make a move as soon as possible.

Hailing a cycle-rickshaw, we contracted a rate of Rs15 (35 pence) to see Kanchipuram’s three most distinguished temples. After visiting the Kailasanathar (devoted to Shiva) and the imposing Kamakshiamon (dedicated to Shiva’s wife, Parvati), we came at last to the Ekambareswarer temple, which was fronted by an outstanding tower 57 metres in height. This particular temple has quite a poor reputation amongst tourists – beggars, cripples, even priests gather from miles around to hassle visitors for money.

The cripples here were the most deformed and pitiful we had yet seen. Elephantiasis is a common affliction in these parts, being easily contracted by walking barefoot in the city’s flyblown streets – the worms bore into the soles of the feet, and work their way up through the bloodstream to bloat the legs or the testicles to gigantic proportions. One victim of this appalling disease lay against a temple pillar, unable to walk. His right leg was swollen to the size of a tree-trunk. Another unfortunate passed close by, cupping testicles as big as melons between his hands. He was quite naked. It was only when I saw this that I recalled John’s story, told us in Mahabilapuram, of seeing a man wheeling his genitals down the road in a wheelbarrow – and mentally admonished myself for not taking him seriously at the time.

Back on the streets in the afternoon, we were soon worn down by an everlasting stream of Indian men pestering us with questions. They wanted to know our names, whether we were married, why we weren’t married, what our jobs were, and how much we earned. They were keen to know how old we were and how we were enjoying their country. But they were particularly curious to know which country we came from. Every person who blocked our path had the same question: ‘You are coming from?’ This was invariably followed by a monetary proposition.

Kevin got so fed up of this after a while that he decided to change his nationality. He was tired of being regarded as a walking sterling note. He was even tireder of everyone trying out the same few English phrases on him. I suggested that he tell them he was Swedish. But Kevin wasn’t satisfied with being Swedish. Sweden wasn’t half far away enough. With his luck, he’d be sure to bump into a succession of Indians who spoke fluent Swedish.

Instead, he began telling people that he came from the planet Mars. And when they didn’t believe him, he started hopping up and down in the street, flailing his arms about in a vivid re-enactment of how he had descended to Kanchipuram from a spaceship. Crowds gathered to watch him. They had never seen a Martian before.

Kevin began to gain confidence, as one by one, beggars, tradesmen and rickshaw drivers bounced off the armour of his new-found origin. Then, just as he had approached the peak of his triumph, he was stopped in his tracks by an eager young ‘businessman’ who was determined to expose his fraud.

The conversation went something like this:

‘Hello,’ said the Indian.

‘Hello!’ replied Kevin.

‘You are coming from?’

‘Mars! I am coming from Mars!’ (Kevin did a little jig, and simulated spaceship descent)

‘You are coming from England.’

‘No, I am coming from Mars. It’s a different planet.’

‘You are coming from England! You have English coins?’

‘We don’t have English coins on Mars.’

‘You are going somewhere?’

‘Yes, I am going somewhere.’

‘Where are you going?’

‘Somewhere.’

‘I take you. I show you the way.’

‘How can you show me the way? You don’t know where I am going!’

‘I take you. You have cigarette? Spare rupee?’

‘What’s a rupee? We don’t have them on Mars.’

‘You are needing dhobi? Clothes-clean? You want guide to temple?’

‘We’re allergic to temples on Mars. Go away.’

‘Where is your room? I bring real English bread-butter to room. Yum, yum! Extra-strong bottle beer also!’

‘You couldn’t get in my room. It’s a one-seater space shuttle.’

‘Yes! I bring mosquito repellent your room! Also Japanese electric-element tea-maker!’

‘No thanks. Push off.’

‘You are needing anything?’

‘No, I’m from Mars.’

‘Ah! You can send me postcard from Mars? I am collecting stamps.’

‘Oh, I give up.’

‘You are from England?’

‘Yes, you’re too sharp for me. I am from England.’

‘Ah! England! You know, I am M.A. Bachelor in English!’

‘I kind of thought you might be. Say, have you ever been to Sweden?’

Deflated, Kevin’s spirits only lifted again when we returned to the Kamakshiamon temple for the festival of the Golden Chariot. Every Tuesday and Friday, we had been told, the goddess Kamakshi (an incarnation of Parvati) was towed round the circumference of the temple grounds in a golden chariot to bless marriages. The rest of the week, Kamakshi’s chariot took it easy in an old garage some way up the road.

The Indians seemed to take Kamakshi’s blessing very seriously indeed. Few of them in this part of the world would have dreamed of getting married without it. On the occasion of our visit, an astonishing 25,000 people had come into town to pay their respects in the temple. The scene, when we arrived at 8pm, was like a Roman triumph – hordes of jostling, excited people crowding in through the narrow entrance to the courtyard within.

We had arrived just in time. Moments after we passed into the temple grounds, the crowd suddenly ceased its activity and a respectful silence descended. It was pitch black. Kevin and I peered at each other, wondering what we had let ourselves in for. Suddenly, from out of the gloom to our right, came the unmistakeable sound of an electric generator starting up. And then there was light. Kamakshi’s processional chariot, previously only a dark, dim shadow, lit up in a blaze of neon-coloured bulbs.

What a sight it was! The entire carriage was plated with 24-carat gold and was festooned with bright flowers, garlands, taffeta and silk tassels. The tiny model of Kamakshi was completely buried in all this decoration. The solid gold figurines of her attendant deities and the two red and gold fairground horses ranged around her on the chariot, were brilliantly illuminated. A great howl of awed appreciation rose up from the crowd.

I had never seen a god propelled by a diesel tractor before. The carriage began to move slowly forward, followed by a troupe of musicians playing an eerie, hypnotic rhythm on squeezebox, horns and drums. An elderly fat priest forced his way up to me through the crowd, and gripped my arm. ‘You see?’ he proclaimed, his face radiant with joy. ‘You see how wonderful is our god? You think that this is all begging. But it is not begging!’ I tried to direct his attention to the growing crowd of acquisitive infants around us, all chanting ‘Rajah! Master! You have pen? You have cigarette? You give rupees?’, but he sprang away the next second – still crowing with ill-suppressed glee – without giving them a second glance.

The processional car stopped four times in all, once at each corner of the massive temple grounds. On each occasion, the two temple elephants heading the procession were drawn to a halt, and a succession of firecrackers and rockets were lit practically under their trunks. They appeared remarkably unmoved by all this commotion. It was impossible for Kevin and me to remain unmoved, however. The combined effect of the jostling, cheering crowds, the wailing, insistent ceremonial music, the smoke and smells of fireworks and incense, and the devilish features of the ghostly gopurams, shot into relief by the bright glow of Kamakshi’s flaming chariot, was the most magical, mystical experience we had had in India to date.

A lot of the magic went out of it, however, when I caught sight of what the temple priest on top of the chariot itself was up to. Each time the car came to a stop, he would stretch his hand out to the multitudes below for their money. Most of them had by this time worked themselves up into such a trance of religious ecstacy, that they were prepared to give him the shirts off their backs. Many people were waving large fistfuls of banknotes in the air, desperate to get his attention. When he looked their way and took their cash, they were so grateful they kissed his feet and fell sobbing to the ground. After collecting everybody’s money, the priest offered it to the Kamakshi figurine on the car behind him, waved a smoke-laden chasuble up and down in front of it, and told all the donors that their marriages had been blessed by Heaven. To conclude the ritual, he knocked a number of flaming incense-coals from the chasuble to the ground. Wherever the coals landed, the crowd fell to their knees groaning and paid them tearful, grateful homage. It was all very emotional.

January 26th

Today we made the acquaintance of Netaji. More accurately, he made the acquaintance of us. And once adopted by Netaji, we couldn’t get rid of him. The moment we showed him the slightest interest, we became his parents, his brothers, his mentors and his best friends. This whole day revolved exclusively around Netaji. He would have liked nothing better, we concluded, than for the rest of our lives to revolve exclusively around Netaji. His desire for our friendship was so powerful and consuming, we couldn’t comprehend it. Let alone reciprocate it.

Netaji first appeared early this morning. He came offering to take our clothes to a dhobi for washing. He returned an hour later with the clothes cleaned, and squatted down on Kevin’s bed for a nice long chat. He remained there the rest of the morning. We learnt that he was seventeen years old (though he looked only twelve) and was still at school. What Netaji hadn’t learnt at school simply wasn’t worth knowing. He gave me the names of every cricketer in every English cricket team over the past ten years. Then he told me how much milk was produced in Sweden last year. Then he told me a whole host of ‘interesting facts’, such as how long it took to build the QE II and other famous ships.

As I listened to this incredible monologue (it went on for two hours without a single pause), I took stock of Netaji. On first impression, he looked like so many other Indian boys – with the usual shock of sleek black hair, the familiar grinning set of brilliant-white teeth, the eager, moist-brown eyes, the clear-skinned but hungry features, and the wiry, undernourished body. But then I noticed the deep scar tracing a jagged path down from his lip to the base of his chin. I asked him what had caused this. He replied that as an infant he had been sitting on the side of the road when a bullock-drawn haywain had passed by. The wheels of the cart had a vicious circle of sharp wire spokes fanning out from the axles. One of the spokes had caught his lip, and had raked the entire left side of his face open.

Netaji informed us that this accident had deprived him of speech for over a year. Kevin and I exchanged a meaningful look. Could Netaji be making up for lost time? We gazed at him in dismay. Would his stream of inconsequential chatter ever come to a stop?

Netaji told us that today was Independence Day in India. He wanted to go somewhere to help us celebrate it. We tried to protest, but he wasn’t to be denied.

‘We go see temple!’ he announced, his bared teeth gleaming in the light of the dim room’s single bulb.

‘No, Netaji! We’ve seen enough temples!’ we protested. ‘Why don’t you go home?’

He shook his head. ‘Parents away for weekend. I stay with you. We go to temple. We go to temple now.’

Kevin groaned and rolled his eyes. He was trying to decide which was worse: going round another boring temple, or spending the whole weekend with Netaji.

Actually, the Varatha Temple which he took us to was well worth the visit. The massive rajagopuram (temple tower) had just been renovated, and was most impressive. So was the wide, spacious Marriage Hall – supported by one hundred finely carved pillars – within. It looked out over a large ghat containing two small temples. ‘Every twelve years god comes,’ explained Netaji. ‘He comes as animal, and each time he comes, new temple built in water tank.’ I looked at the ghat, and did a rapid mental calculation. In another hundred years, there would be so many temples in there to commemorate Vishnu’s visits that he wouldn’t be able to come anymore.

Netaji asked us if we were hungry and then, without waiting for a response, ran off out of sight. He returned with three banana leaves full of what appeared to be a mush of greasy, bright yellow maggots. ‘Sweets!’ announced Netaji. ‘Yum, yum!’ He told us it was a mixture of lemon-rice, ladau (sugar) and onions. Kevin’s face registered absolute disgust. Netaji didn’t seem offended when we gave him our portions. He ate the lot, and thoroughly enjoyed it.

We had planned to lose Netaji outside the temple, but he had other plans. ‘We go see film!’ he said. ‘English film! You like!’

Actually, this didn’t sound a bad idea at all, so we decided to string along. Off the bus back in Kanchipuram, Netaji sprinted off – with no warning – down a backstreet. We followed at a run. Neither of us had any idea why we were running. We were quite breathless by the time we caught up with him, having scurried down a bewildering warren of hidden lanes and narrow alleys. I clung onto Netaji, and demanded an explanation.

‘We run quick! Friends no see, parents no find out!’ he replied.

‘Parents no find out what?’ I quizzed him.

‘Parents no find we go see sex film!’ tittered Netaji.

We looked at him in alarm.

‘Yes!’ exulted Netaji, clapping his hands together in excitement. ‘Sexy film! English sexy film! You like!’

Before we had a chance to protest, he had dragged us inside the nearby cinema and thrust us down into two empty seats. Then he ran off to another part of the dark interior and sat somewhere else. He apologised that this was necessary, since it wouldn’t do for him to be recognised in such an establishment with two foreigners. Before leaving, he assured us that we would love this film. It was the most popular movie playing in town.

The film was called Together With Love. It wasn’t a sex film at all, but an educational film for expectant mothers! The screen was alive with heavily pregnant ladies wallowing around doing exercises on the floor of a pre-natal classroom. Some sort of raucous American commentary was going on in the background. It was so loud as to be completely unintelligible. Kevin and I held our hands to our ears, and looked around at the audience in the cinema. They were all men. All we could see of them was rows of staring, excited eyes and grinning teeth. Everybody was riveted to the screen. The only times there was any reaction was when a naked female breast loomed onto the screen, and then a ripple of nervous, lascivious laughter swept through the audience. We were quite at a loss to understand this – all the breasts which came into view were heavily swollen with milk, and generally had a thirsty baby attached to them.

Kevin and I suffered twenty minutes of this curious spectacle, and then left the cinema. Netaji leapt out of his seat and followed us outside. On the walk back into town, we tried again and again to lose him down one or other of the numerous backstreets, but with no success. Whenever we thought we’d finally given him the slip, back he’d pop into sight laughing and skipping along about ten yards ahead of us. He never came any closer, and was never farther away. At this distance, he could both pretend he didn’t know us (in case his friends or parents turned up) and yet be pretty sure of retaining his hold on our company. Netaji was a very sharp cookie indeed.

We did get rid of him in the end, though. Back at the lodge, Netaji got collared by five chums on the roof who wanted him to share a hash cigarette with them. This offer proved irresistible, Netaji’s vigilance slipped for a moment, and we bolted thankfully out into the freedom of the streets.