Revelations in Rajasthan

Many western travellers go to Rajasthan for a rest at some point. One of the quietest states in India, with a relatively low population, it is also one of the friendliest and most attractive. Having now journeyed the length and breadth of this country, I decided the time had finally come to give myself a ‘holiday’ before returning to England.

Teaming up for this excursion with Jenny – who had turned up from Nepal yesterday – I boarded the noon train to Udaipur and joined her in the ladies’ compartment. It was nice and quiet in there – we were the only two occupants.

Things went well until, at 6pm, we came to Rajgarh (just up the line from Jaipur) and then our luck ran out. Firstly, the train developed a fault and stayed put in the station, awaiting repairs. Then our compartment was suddenly invaded by a large family. The parents were quiet enough, but their three boisterous children created havoc. They leapt and cavorted all over the seats, shrieking loudly the whole time. Meanwhile, the parents – making no attempt to curb their wild spirits – just smiled at them indulgently, apparently condoning their attempts to demolish the carriage. There was also a fourth child, a small baby, present. It lay in a small bundle on a seat, sound asleep through all the bedlam. The other children, not liking this non-participation at all, decided to wake it up. One of them began playfully head-butting it on the seat, while the other two shoved entire orange segments into its tiny buttonhole mouth. It wasn’t long before it too started screaming, providing a perfect backdrop to the resumed cacophony of its elder siblings.

I beat a tactical retreat at this point, leaving the stationary train for a brief foray into Rajgarh village. Poor Jenny, suffering from the heat and the children in the compartment, croaked relief as I returned to hand a bag of apples and mandarin oranges through the window. She informed me that we had now been delayed over two hours.

Shortly after the train set off again, at 8.30pm, I was shunted along by the guard to my correct sleeping berth, four carriages down from the ladies’ compartment. I found my ‘reserved’ bunk full of other passengers’ luggage. And they were most reluctant to move it. Only when I indicated that I was likely to be sick all over them unless I was allowed to lie down, did they finally relent and clear the bunk for me.

The lights in the compartment went out. The Indian below began snoring, but that was okay. I was used to that. Everything else was pleasantly quiet, and I prepared to get a good night’s sleep. Suddenly, however, another man arrived and rudely shook the snoring Indian awake. He wanted to talk to him. A loud, spirited conversation sprang up beneath my weary head. I took about ten minutes of this and then, realising that it was likely to go on all night, I told them to put a sock in it. The ‘visiting’ Indian looked up at me in astonishment. He evidently did not think that holding a loud conversation in a compartment full of sleeping people at midnight constituted any sort of nuisance. But he took the hint, and left.

A few minutes later, I heard an odd hissing noise below, and leant over the bunk to investigate. He was back. My nocturnal nemesis was now kneeling below his companion’s bunk, resuming his conversation with him by means of agitated whispers. Oh well, at least I’d tried. I put my earplugs in, and eventually drifted off to sleep.

April 15th

Arriving in Udaipur, we took a cab down the quiet, dusty streets, and booked into the Rang Niwas Palace Hotel, which in better days accommodated the Maharani of Udaipur’s guests. Over a century old, it was still however a marvellous building – set in green gardens full of exotic birds, sculpted bushes and orange-blossomed acacia trees. As we moved in. the lodge’s cocker spaniel was wearing itself out barking at a vagrant cow that had wandered in from the street. Then the cow left and all was quiet.

After a refreshing shower, we walked along to Udaipur’s magnificent City Palace. The views from its turrets and balconies were quite breathtaking, particularly those of the famous Lake Palace below and of the desert mountain range in the far distance. The palace itself was a marvel – jewelled mirrors, ornate mosaics, intricate latticework windows and colourful peacock sculptures. These treasures combined with rich silverwork, beautiful tapestries and awesomely decorated courtyards, to produce a magical effect of opulence and extravagance.

Walking down to Pichola Lake, we then took the popular speedboat ride across to the fabulous Lake Palace, situated in the middle of the landlocked waters. The place, now turned into a hotel for rich tourists (Rs300 per night for a room), had plush carpets, antique t’anka tapestries on the walls, and grandiose chandeliers and brass lamps dripping from the ceilings. Jenny and I rested in the ‘Coffee Room’, watching as flocks of sparrows swept back and forth over our heads and breathing in the sweet smell of honeysuckle emanating from the nearby tea garden. Soon, as the sun set over the metallic-red lake, we took our leave and returned back to land.

We dined this evening at the nearby Roof Garden Cafe, an excellent viewpoint from which to observe the twin royal palaces. At night, both palaces are beautifully illuminated and stand forth like a pair of gem-studded, glittering crowns on the regal brow of the hill opposite.

While we were looking at the Roof Garden’s menu – which offered COD COFFEE and FRUIT SALAD WITH RESINS – a sleek, refined Indian sat down at our table. ‘Call me God,’ he announced, translating his Hindi name, Dev, into English for us. He had seen my Walkman cassette recorder and was interested in buying it. He remembered seeing us in the Lake Palace hotel earlier, for this was where he worked, managing the coffee bar. Aged just 26, Dev was very affluent by Indian standards, managing to support a large family in a big house with three flats, and able to fully indulge his two favourite hobbies – riding powerful motorbikes, and drinking large rum and cokes. All he needed now, he reflected while smoothing his neat pencil moustache, was a rich wife. The rest of the evening he spent staring at Jenny. She looked eminently suitable.

April 16th

Udaipur at this time of year is incredibly hot. The sun beams down like a laser, and animals and humans alike retreat gasping into the shade, and go to sleep. Somehow, Jenny and I roused ourselves to activity. Hiring bicycles, we undertook a sightseeing tour of the city.

Cycling was surprisingly cool. We creaked happily through a number of identical sleeping streets, and arrived at Udaipur’s famous puppet exhibition, the Lok Kala Mandal. Here we were the only guests. The yawning attendant told us to sit on a carpet and wait for the puppet exhibition. Twenty minutes later, nothing had happened and we rose and left. On the way out, Jenny pointed out a wall photograph of a young native girl in full tribal regalia. The inscription read:

The Adivasi Belle from Gujarat is child-like in her ways. She combines a jazzy blouse with heavy bangling necklaces and intricate bracelets. What does she care for aesthetics? She is a child of the soil!

Behind the gardens of Sahelion ki Bari, we later came across Udaipur’s ‘Science Museum’. The most recent scientific advance depicted here was model showing how electricity was invented. Elsewhere, there was a collection of the most bizarre exhibits – some old skulls in a corner, a damaged stuffed bat (with a fox’s head) hanging off the wall, and a vast number of small animals and reptiles crammed into pint-size milk bottles. Then we came two large glass cages. The first contained a life-size model of a naked woman, with detachable breasts and a detachable face. Behind the face lurked some sort of green cancerous fungi sprouting all over the surface of the brain. In the second case stood a skeleton wearing a green and white sari. It had a broken arm, which hung limply at its side, and its lifeless skull gave us a macabre, empty grin. We concluded that it was either an ex-founder member, or the museum’s original ticket lady still waiting for her pension.

Reaching Fateh Sagar Lake, we took a small boat over to the Nehru Park, a beautifully landscaped garden island full of bright maroon, orange and green flowers and foliage. The small restaurant here served only ice-creams and drinks. We had a lot of difficulty with the ice-creams. A flock of hungry sparrows settled all around us waiting for leftovers. It was just like a scene out of The Birds.

Our final call, the Jagdish Temple, was too much for Jenny. The heat finally overpowered her, and she lay panting at the bottom, unable to get up the steps. I climbed up alone and found a group of Rajasthani women – dressed in traditional bright, flowing robes – seated within the cool interior, singing religious songs. They were accompanied by a skilled tabla-drum player, and the songs were both tuneful and atmospheric. Shortly after I had sat down to listen, a doddering old man dressed in a little white dhoti appeared and began performing a shuffling dance to the music. His hands moved to and fro restlessly as he tottered about, suggesting the spirited motion his feet would have liked to achieve had they not been so unsteady. Suddenly, the song changed and the women launched into an altogether more frenetic number. At which point, the old dotard stopped in mid-shuffle, and shambled slowly off the floor looking affronted.

After handing in my shoes at the entrance, I was compelled to view the temple itself at high speed, for the ground was now white-hot from the sun and sizzled the soles of my feet whenever I paused to look at anything.

Having returned to the Rang Niwas, I tucked into a huge plate of grapes, apples, bananas, mangos, chikus (a bit like dates) and mandarin orange segments, while chatting to one of the hotel’s owners. This was a young fresh-faced Hindu called Bahti. He had a wistful, resigned expression, particularly when talking about women and sex. Twenty-two years old, he was unhappy that caste and religious restrictions made it impossible for him to make friends with the opposite sex. The first woman he would know on an intimate basis, he confided, would be the wife ‘chosen’ for him by his mother. He had seen the woman to whom he was betrothed only twice to date, and disliked her intensely. I asked Bahti when his marriage would take place. ‘Oh, I don’t know,’ he sighed dismally. ‘My mother will take care of that. I’ll be the very last person to know.’

Finishing our supper at the air-conditioned Berry’s Restaurant in Chetak Circle, we emerged into the dark street and saw a large sign saying: ‘English and Udaipur Wines’. Fancy finding a wine shop in India, we thought, and approached it eagerly to make a purchase. I gave the proprietor an expectant smile, and asked to see his selection of wines. He looked up and replied: ‘Wine? Oh, I am sorry, but we do not have any wine just at present.’

‘No wine?’ I echoed flatly, then insisted: ‘But you’re a wine shop – it says so on your sign!’ The man gave me an apologetic look. ‘Yes, sir,’ he replied. ‘We are most certainly a wine shop. But we are not selling wine. Here, when people ask for wine, they are thinking of buying whisky or rum. Not wine.’

April 17th

After gorging ourselves on mangos, we moved out by bicycle in search of the infamous Pratap Country Inn, a hotel with such a bad reputation that it simply begged a visit. According to Bahti, it was run by a middle-aged relative of his who lured susceptible western women into his lecherous embraces by giving them free dips in his mud-hole swimming pool and free horse-riding lessons in his ramshackle stables afterwards.

We set out at 10.30am. By noon, we were hopelessly lost. And my bicycle had developed a flat back tyre. I left it in a repair shop we found in the middle of nowhere, and sat down with Jenny in the shade over a cup of tea. The bicycle-repair man came over to give me an offer I couldn’t refuse: the bike needed a new valve fitted and this would cost me twenty rupees. He had made sure I couldn’t refuse by removing the old valve, making an inexpensive temporary repair impossible. Piqued, I told him I couldn’t afford the new valve, and wobbled off again with the flat tyre.

We never reached the Pratap Country Inn. Somehow, we ended up at the Maharajah of Udaipur’s hunting lodge at the Hotel Shikarbadi. The only life we had seen for miles was a pondful of static water-buffalo. As we passed up to the hotel, however, a host of large white monkeys with wise, black faces darted out to greet us. So did the hotel’s strange doorman, an elderly Indian who rushed towards us in a flowing scarlet dress-coat, flourishing a long, deadly scimitar. He dismissed our show of alarm, and directed us to the restaurant for drinks. Relaxing here in cool, shaded green wicker chairs, we asked the waiter if we could possibly use the hotel’s swimming pool, for the heat had dried us to a crisp. He said he didn’t know, but would find out from the manger. The manager’s office was just round the corner, but the waiter probably decided the walk was too arduous. He preferred to use the telephone. It took him twenty minutes to get through. He spoke to the manager, and then returned to tell us that yes, we could use the pool, but it would cost us twenty rupees each. A short, hurried consultation, followed by a pooling of resources, and we agreed to pay the required fee.

The Shikarbadi had an excellent swimming pool. It had luxury tiling, was ideally positioned to catch the best of the sun, and was surrounded by reclining couches in which to get the perfect tan. The only thing it didn’t have, however, was water. We reached the edge of the pool to find it quite empty.

Somehow, despite the bicycle’s flat tyre, I negotiated the five kilometres back to Udaipur without incident. And there were some charming sights along the way, particularly of the brightly-attired Rajasthani women – their robes of yellow, green, red and orange billowing behind them as they passed by (often singing) with panniers of food or bales of hay balanced on their heads. Later, we saw an overheated elephant with a load of pots and pans on its back, standing in a ditch, cooling off in the shade of some trees with its sleeping master. Not so lucky was the heat-maddened bull which ran amok down the street as we approached the City Palace. It was so crazed, it nearly butted Jenny off her bicycle.

Back at the Roof Garden Cafe, ‘God’ turned up again. His urbane veneer of sophistication was slipping tonight. He confessed that for all his money, his good job and house, and his rich friends, he felt something lacking. He didn’t know what. To stop himself thinking about it, he asked the waiter to put on his favourite record. It was a mournful soul number which, when slurred out of the restaurant’s decrepit tape machine, crept long at a funereal pace. It opened with the ominous statement: ‘This...is...the...saddest...day...of...my...life’, and it depressed us enormously.

But Dev loved it. He said it put him in mind of a beautiful woman he had once loved who had spurned him for someone with more money. And again, he gave Jenny his undivided attention all evening.

April 18th

We only just caught the early bus out to Chittorgarh this morning. One second, the driver was leisurely consuming a sticky jellaby (sweetmeat) and sipping a cup of tea; the next, he had leapt into his small cockpit and roared the bus out of the stand. Which was rather unfortunate for Jenny, who had just sauntered off to buy us some breakfast. By the time she returned a minute later, carefully carrying two cups of cha and a bunch of bananas, the bus-rank was empty. She looked thunderstruck. It was only with difficulty that I persuaded the impetuous driver to reverse back up and collect her.

But the whole of the rest of the journey went like this. No sooner had the bus stopped, than the driver was off out of his seat to get his cup of tea, and we didn’t see hide or hair of him until, when we least expected it, he was magically back in his seat and raring to go again. It was a nerve-racking experience. The first couple of stops, we disembarked to get some tea ourselves, but no sooner had we queued up and purchased it than the driver had rematerialised in the bus, his teeth bared in a manic grin, and we had to abandon our drinks untouched and race back to the bus again before it skidded off without us.

Apart from that, the four-and-a-half hour journey was smooth and pleasant. We came into Chittorgarh relaxed, and with our plan of action ready. We had just two hours spare before our next bus left at 3pm for Ajmer. Moving into high gear we hired a rickshaw and told the driver to take us round Chittor’s main attractions as quickly as possible.

Chittorgarh is a massive fortified city with a very famous history. In olden days, whenever it was attacked and saw its position hopeless, all the men would ride out to be slaughtered in one last glorious battle while all the women and children committed suicide. Each time this happened – and there had been three such ‘Jauhars’ of note – almost the entire population of the city had been wiped out. The miracle was that it managed to restock itself each time to ready for the next mass suicide.

Our lightning tour took us up through Chittor’s seven fortified gates, into the modern Fateh Prakash Palace, and then up to the top of the impressive Tower of Victory, with a magnificent view of the whole fort ruins. We then passed round the Mahasati site – a sad, lonely place where many brave wives and concubines joined their husbands on the funeral pyres – and finished up at the lovely Padmini Palace, set in calm, tranquil courtyards and gardens. It was on the pavilion of this palace, so the story goes, that the beautiful princess Padmini stood when the emperor Alu-ud-Din saw her reflection in a mirror and fell in love. He was so infatuated that he destroyed the whole of Chittor to get her. In the end, Padmini decided to cheat him of his prize by killing herself – yet another example of this unhappy people’s remarkable talent for self-destruction.

Leaving Chittorgarh, we came to Ajmer, and caught the short connecting bus to Pushkar, arriving there shortly after dusk. A small oasis of civilisation located on the edge of the Great Thar Desert, this town had been recommended to us by many other travellers as the most pleasant place to stay in all India.

April 19th

From the parapets of the cheap but palatial Pushkar Hotel, I noted this morning that we were staying on the banks of a small inland lake. There was a fine view of the whole town, the small houses and shops glittering marble-white in the reflected light of the rising sign.

Coming down for breakfast, I met Paul, a friend from Kodai, who advised us to seek out the Krishna Restaurant, apparently the best place for food in town. It took us a long time to reach it, however. There were too many distractions. The quiet, friendly streets of Pushkar are absolutely crammed with attractive, colourful shops selling all manner of marvellous clothes, shoes, curios, souvenirs, tapestries, and wall-hangings. With the possible exception of Kathmandu, it is the very best place to meet interesting people and to buy interesting things – though the very worst place to go if one is a poor traveller living on a very tight budget. There is far too much tempting stuff to buy here, and it’s all far too cheap to resist.

By the time we reached Krishna’s for breakfast, it was lunch-time. Within, I discovered my old trekking companion, Joseph, sitting in a corner with a bag of guava pears. It was a very happy reunion, enlivened by the Krishna’s interesting menu. This offered PLAIN SLUICE, MACRONY CHEESE, VEGE SENDVICH and JEM TOST ONE PLATE. It also bore the stern warning: SUGGAR CHAGGE WILL BE EXTRA! The Krishna also had a speaking fridge. It stood in the corner and was plastered with stickers saying things like: WELCOME! and DON’T TOUCH ME! and I AM VERY COLD! It was a real conversation piece.

After a delicious fruit salad curd, followed by a curious porridge made from chapti wheat, I suggested that Jenny have her hair cut. It was getting too long for comfort in this heat. But the Indian barber we found didn’t understand English too well. Instead of cutting just one inch off, as she had requested, he left just one inch on. She now had as much hair as me – i.e. hardly any. But the result suited her well. And as her flowing auburn locks fell to the floor, Megan turned up. She had left the other Scottish girls behind in Jaipur, and had travelled over to join us here in Pushkar.

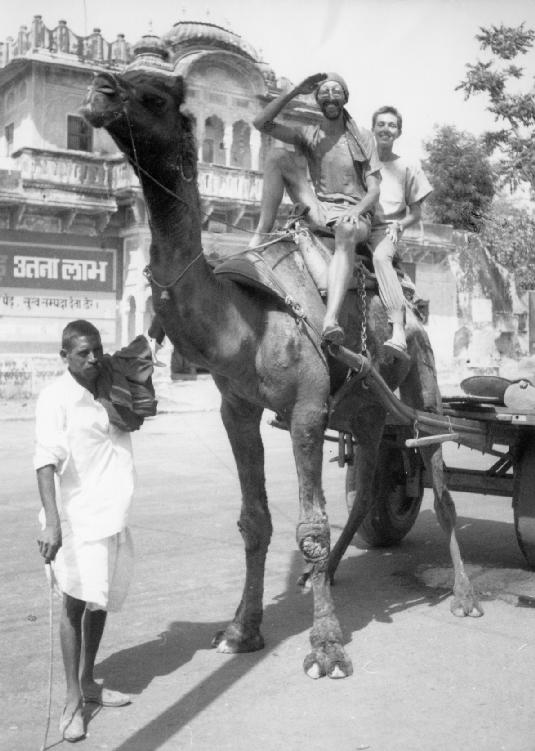

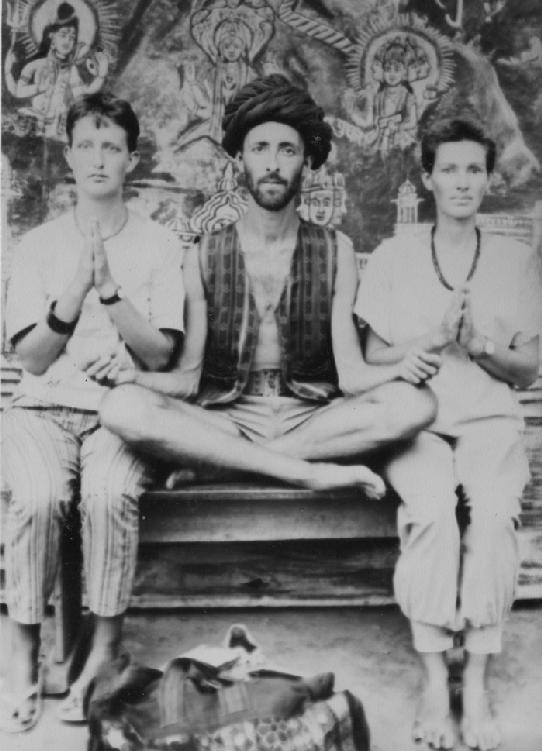

The heat of the day had now reached fireball intensity. To finance further shopping expeditions, I now sold my Walkman and we returned – part of the way on camel-back – to move all our bags over to the Sarovar Tourist Bungalow, where Joseph was staying. This turned out be the most luxurious (and least expensive) lodgings I had taken in India. My room was a tiny one – in an octagonal castle turret – but the rest of the building, and its facilities, were unsurpassed. Festoons of green plants, gardens of bright-hued trees, lawns of lush grass, beautiful views of the lake, and the awesome mountain backdrop made this the perfect spot in Pushkar in which to wind down and relax. After a few hours of basking in the sun and swimming in the lake’s calm, warm waters, we gave this place our vote for the nearest thing to paradise we’d found in all India.

We only exerted ourselves once more today – to steer Megan off to the barbers to get her hair cut too. She also emerged practically bald. Otherwise, all we found to do in Pushkar was swim, sunbathe, go shopping, and drink ice-cold Limcas and lemon sodas.

April 20th

Before it became too hot, we took an early morning trek across the rolling dunes of the desert and up to a nearby hilltop temple.

Once out of Pushkar town, the desert sands stretched before us into infinity. We crossed them in silence and came half an hour later to the foot of a giant stone causeway, some thousand feet high, which led up to the temple. Reaching the top – a hot, sweaty climb – we entered the tiny shrine to find a refreshing cup of mint tea waiting for us. It was served by an Australian girl who, dressed in native garb and fluent in Hindi, was being allowed to attend the temple. She told us that it was some two thousand years old, and had been erected in honour of the god Brahma’s first wife, Savitri.

The views were quite superb. Below us, Pushkar and its lake glistened like a bright blue tear in the eye of the surrounding desert. Barren plains and mountains lay north and south of the town, while to the rear a speck-size mule train was ambling off into miles upon miles of arid, undulating sands. We spent an hour here, then returned back down before the sun became too intense for walking.

Going back into town, we stopped off at the pink-domed Brahma Temple, apparently the only temple in all India built specifically for the god Brahma. Which we found odd, since Brahma is the central figure (Creator) in Indian mythology. The temple itself was the cleanest, quietest and most attractive we had ever come across. And all the local people paying their devotions here were extremely welcoming.

The rest of the day was spent in spending too much money. Everywhere we walked, our pockets emptied to purchase embroidered waistcoats, silk trousers, mirror-inlaid bags and all manner of baubles, bangles and beads. Our final expense of the day, however, was the most interesting – having our photograph taken by a grizzled old Indian owning an antique Victorian box-camera. It took a whole hour for him to set up his equipment and to produce a satisfactory negative. As we waited, sitting on a low bench at the roadside, our gaze shifted between the two donkeys that had begun to copulate in the middle of the street and the small girl with eight toes on her left foot who had come to supervise proceedings. The photo, when it was finally produced, was remarkable. It had the tinted, vignetted look of a picture taken last century!

Pushkar struck us at the cleanest, most relaxed place in India any of us had yet visited. It wasn’t noisy, overpopulated, stressful or anything like as dirty as most other towns or cities. The only hubbub came from the odd pack of wild dogs, the occasional shriek of a peacock and the wild chattering of temple moneys. As for the human population, they were generally sound asleep.

April 21st

Before paying our farewells to Pushkar, we made a short tour of the holy ghats lining the banks of the lake. These were charming places, with a relaxed and friendly approach to visiting tourists. Only one ghat gave us problems: the girls were instructed to make puja (devotion) to the god of the lake. They were seated on the steps of the ghat, with their feet immersed in the water, and their cupped hands were filled with flower petals, rice and coloured powder. After casting this offering into the water, they were given a dried husk of coconut each to recite the ‘Brahma Puja’ over. This prayer, which the priests expected Megan and Jenny to repeat parrot-fashion after them had a brain-washing begging routine built into it. Thus, in between various regular prayers to Brahma, there would appear the curious instruction: ‘You-give-me-twenty-one-rupees-one-hundred-and-one-rupees-no-matter-what-you-give.’ When the girls only gave the priests the time of day and no rupees at all, there were angry scowls and muttered curses all round. Even here in Pushkar, we were saddened to note, religion and money went very much hand in hand.

We went down the high street towards the Krishna Restaurant through a barrage of friendly one-liners from local people. None of these passing comments – which ranged from old favourites like ‘Good rate dollars’ and ‘You are coming from? to new curiosities like ‘First time Pushkar?’ and ‘Fruit Porridge’ – seemed to require any reply. People made them, then went on their way. Rajiv, the affable manager of the Krishna, had a lot more to say for himself. He was a 25-year old Brahmin, very concerned about his ever getting married. Not only could he not afford to keep a wife and her entire family in his house, but even if he had one, he would hardly get to see her since he had to work 14 hours a day to look after the restaurant. All this, however, was not the main problem. The main problem was that he had an elder brother. And his caste required that all the children in a family marry ‘in sequence’ – eldest first. The only way that a younger sibling could jump the queue was when elder brothers and sisters had mental or physical infirmities which made their own marriage unlikely. Rajiv’s elder brother, however, was in perfect health. And he had no intention of getting married. Which meant that Rajiv could expect to remain a bachelor for many years, perhaps the rest of his life.

The moment we left Pushkar, our troubles started. Out of this oasis paradise, we were quickly thrown back into ‘real India’ again. Even getting out of the hotel was a problem. I deducted ten rupees from my bill in respect of the dhobi-wallah having dyed all my clothes purple, but the manager became awkward and had his entire staff bar the door to my exit. Rather than return home a cripple, I paid the ten rupees.

A pleasant roof-top journey on the bus back to Ajmer was followed by an arduous two hours touring round every photographic shop trying to get a sensible price for my camera. I was now low again on funds, and had to sell it. The camera eventually went for Rs800 (£20) but by this time it was far too late make Agra tonight. We decided to spend the night in Jaipur instead.

The road to Jaipur was littered with wrecked vehicles – battle-scarred victims of recent crashes – and our journey was repeatedly delayed as the roads were being cleared to allow us passage. Two crash scenes were particularly harrowing, with the offending driver of both smash-ups being set upon and beaten to a bloody pulp by the passengers of the other vehicles.

We booked into a troublesome lodge in Jaipur called the Hotel Golden. This tried to charge us a hundred-rupee ‘deposit’ (five times the room rent!) and gave us rooms in which all the door locks fell off. But this wasn’t the worst of it. The hotel’s main problem was cockroaches. It was absolutely crawling with them. I came back to my room this evening after a wholesome meal of thali to a full-scale conflict with the insect kingdom. It started when I switched on my light and noticed that the full packet of ‘Coconut Crunchies’ I had left on my table now contained just two biscuits. An army of ants, forming a neat black line from the wash-hand basin to the table, had eaten the rest. But they hadn’t done it alone. I picked up the biscuit packet, and three giant cockroaches scuttled out. I picked up the table, and scores more dropped off the bottom of it. Before I knew it, the whole room was alive with scurrying roaches. They moved devilishly fast, and had iron-hard shells. Consequently, it took me a long hour to root them all out. Then I went over to Megan and Jenny’s room to warn them against leaving any food out for insects. But they weren’t interested. They had something much worse than cockroaches to worry about. A large black rat had just run out from under Megan’s bed and was now roaming around in the room’s squat-toilet. A very uneasy night followed.

April 22nd

Our only pleasant memory of Jaipur was its ice-cream, which was delicious. A traveller over breakfast told us we should have been here during the ‘marriage season’ recently, for then the city was far more colourful and friendly. He told us that every Indian in town had rushed to get married this spring after hearing that it was an astrologically auspicious time. Every marriage had been celebrated by a big procession down the high streets. The contrast between rich and poor marriages, our friend told us, was very marked. Wedding processions for the rich had plush carriages, white horses, and guests following on, holding neon-lit tubes. The poor, however, had no such finery. All they had was a tractor. And an auto-rickshaw. The rickshaw went on ahead, with a few streamers flying from it, while the guests and the gifts chugged up the road behind it on an old tractor.

Taking the bus on to Agra, I found myself sharing a seat with a portly Indian in white Congress Party dress. He was an incurable fidget. He had a bag at his feet with a Russian-made toy truck which he was itching to play with. Every minute or so, his hands would dip helplessly into the bag to spin the truck’s wheels or to stroke its glossy paint.

Agra was again a scene of much hassle from rickshaw drivers, beggars and unemployed Indians wanting to change our dollars or to earn commissions by guiding us to cheap lodgings. Wishing to see the Taj Mahal unhampered by luggage, we left all our bags in a single cheap hotel room. The owner of this lodge insisted that I take a look at his ‘garden’, saying it would be of great interest to me. It turned out to be a small field at the back of the lodge, packed to capacity with cannabis plants.

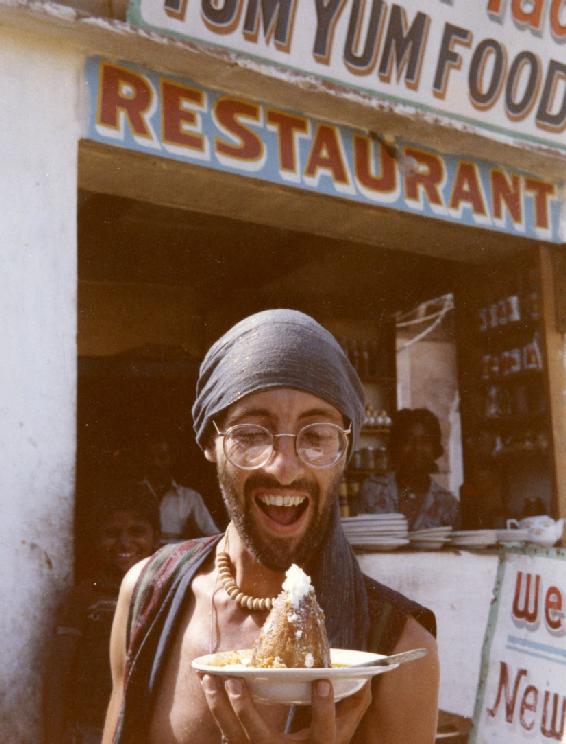

Taking rickshaws to the Taj, we dropped off at Joney’s Place, a restaurant much recommended by travellers. It is owned by a happy young Indian (Joney) who combines a real interest in Westerners with service of very fine food. After welcoming us to his establishment, he asked us to sign his ‘guest book’ which was full of tributes (often humorous) from satisfied customers, and then he gave us his YUM YUM MEENU. This contained a ‘big breakfast’ of PORICLG and CORNFX, ONE POID EGG, and YOGURT PANKAGE. Joney was particularly keen that we try his STAFFED POT (stuffed potatoes) and VEG BOMB (?). So we did. They were excellent.

We came into the Taj by the quiet South Gate. By the entrance, a small Limca stand was advertising its wares: ‘LOOK HERE’, said its sign. ‘MAY I EXCUSE YOU FOR VERY ICE-COLD DRINK OF FREEZ?’

My second tour round the Taj Mahal was altogether more satisfying than the first one. Primarily, because the intense heat was now on the decline, and the blinding-white light playing on the marble monument had been replaced by a warm, orange-cream glow which rested very easy on the eye. Seated on the green lawns, we again marvelled at the ageless quality of this structure. It hardly seemed the work of human hands. Which is probably what its architect, the cruel Shah Jahan wanted people to think and why he (apparently) had the hands chopped off all the principal sculptors, lest they duplicated their remarkable achievement.

We were so taken with the Taj that we hopped on the 6.45pm train back to New Delhi only just before it pulled out of the station. This was the famous ‘Taj Express’ – the nearest thing to luxury travel for ordinary passengers that India can provide. Not only was there no crowding and lots of room but it was very well air-conditioned and very clean. Best of all, in view of the aching calluses on our backsides, it had well-padded seats. There was even a drinks service available – a man moving up and down the train selling ice-cold bottles of some fizzy drink called ‘Tingler’.

Back in Delhi at 10pm, we returned to the Hotel Queen. Only to find it half demolished! It was in the process of being radically ‘redecorated’. We had to share the one room left vacant between the three of us. And as we moved in, the hammers and mallets went back to work outside. Would our room be still standing when we woke in the morning? Or would it be just a heap of rubble like the others, with us buried under it?

April 23rd

Most of this day was spent queuing up for cinema tickets. Delhi was going wild about the arrival of Shiva Ka Insaaf, India’s first 3-D movie, and we decided to see what all the fuss was about. It was a fateful decision. The size of the seething ticket queue outside the Sheila cinema was formidable. And the ticket window was regularly infiltrated by people who could not be bothered to queue up, or by touts buying blocks of tickets to sell on the streets at inflated prices. Every so often a policeman would appear with a heavy lathi club to drive these interlopers off, but even when beaten soundly over the head they got up smiling and began pushing in again.

I got in at the back of the queue at 10am. By the time I had reached the front, it was noon. And just as I was about to hand my money through the forest of other hands pressed in the ticket window, it mysteriously closed ‘for lunch’. Poor Megan, sizzling away on the white-hot pavements, nearly burst into tears at this point. To retrieve the situation, I tracked down the cinema manager and he promised to have three tickets waiting for us at 3pm.So we went away and came back again at 3pm, and asked for our tickets. But they weren’t there. The manger had forgotten. I ground my teeth, and prepared to rejoin the milling scrum of people ‘queuing’ round the ticket window. Suddenly, the situation was saved. A helpful Indian, seeing our predicament, jumped the entire queue for us and procured us three tickets. He did it simply out of the kindness of his heart. And he did it in two minutes flat.

The last event of the day was a musical entertainment outside the Metropolis Restaurant. A tabla-drum player, accompanied by a flautist and squeezebox player, was hammering out a frenetic, hypnotic rhythm in the road, with members of the large, pressing audience being invited to dance to the beat. One local boy promptly did such a good impersonation of a whirling dervish that some appreciative observer stuck a filthy two-rupee note in his open mouth. The clean-cut youth didn’t like this at all. He stopped dancing, spat the money out, wiped his mouth, and strode off looking mortified.

April 24th

Queuing up to see Shiva Ka Insaaf outside the cinema, all eyes were fixed on Jenny and Megan. They were the only women in the queue. But as we filed up to the entrance, attention quickly switched from them to something far more interesting – a determined assault on the entrance door by hordes of Indians trying to get in without tickets. They dashed up the steps, got clubbed down again by a flurry of flashing lathis, scraped themselves bleeding off the ground, and dived straight back in again. The cinema manager, dispensing 3-D spectacles at the door, surveyed this with growing excitement. At last, no longer able to contain himself, he vaulted over the ticket barrier, snatched one of the lathis out of a policeman’s hands, and waded into the crowd of illegal entrants, cracking as many heads as possible before reluctantly returning to his post.

The film itself was gloriously bizarre. It featured a meek, mild-mannered and incredibly obsequious Hindi youth who kept changing into a super-hero called ‘Shiva’. Shiva was very fat and wore a kinky leather outfit, complete with black mask, flowing black cape and pointy-toed black booties. He had gained his incredible Shiva-powers (overtaking villainous Chevrolets on a Shiva-bicycle, head-butting gymnasium punch-bags for hours on end without apparent brain damage, and leaping over a swimming pool full of floating logs for a big helping of Shiva-samosas) by praying at a Muslim mosque, a Catholic church and a Hindu temple. Oh, and by dedicating himself to falling off high buildings for worthy causes.

Whenever the portly hero arrived, the film soundtrack erupted in a triumphant blare of noise, and a whispered chant of ‘shiva!...Shiva!...SHIVA!’ built up to a bellowed boom in the background. This was just in case the audience hadn’t guessed who was coming. When not dressed in leather and prancing around doing good deeds, Shiva was a feeble news reporter cowering under the petulant criticism and cross intolerance of the ‘heroine’, his editor. All she had to recommend her (as far as we could see) was a pretty good singing voice. Which meant that the otherwise omniscient Shiva was completely blind to her other failings. Like all other Indian film heroes he was a hopeless sucker for a good song.

The film as a whole, despite tidal waves of charging, militant music announcing every dramatic 3-D effect, was hugely enjoyable. It put us in just the right mood to enjoy our other main event of the day – visiting a luxury swimming pool in one of Delhi’s plush hotels. This was something I had been looking forward to for months, having heard that for a reasonable charge poor tourists like ourselves could avail themselves of the very best hotel facilities that India could provide.

Our first choice, the Imperial Hotel in Janpath, was too expensive. But then we came to the nearby Hotel Kanishka, which charged only Rs25 each for use of its luxury pool and associated mod cons. We spent a marvellous afternoon there, lying on sun-beds, swimming, and having drinks brought out to us by the pool. It gave us a glimpse of how the rich tourist in India can expect to live.

Leaving the restful, enclosed haven of the hotel, however, it was back to real India again. We found ourselves stranded at the wrong end of town, every rickshaw and taxi in Delhi having decided to go on strike while we lazed obliviously by the pool. It took us a long hour trampling round the city to find just one young rickshaw ‘blackleg’ who would defy the strike to take us home.

I packed and made ready to leave India. Then, with the approach of evening, I took the girls down to Gobind’s for a farewell meal. It was a small affair of fruit salad and curd, with lemon tea, taken on the upstairs balcony. From here, I took my last look at Indian life passing by on the streets below. It was the same as usual: a busy, chaotic, yet strangely harmonious potpourri of noise, colour and smells. Beggars huddled in doorways, children cried and laughed and ran wild, rickshaws bleeped and hooted and ploughed onwards relentlessly, sacred cows lay unconcerned in the middle of the road, and tourists picked their way carefully round the excrement and the gaping open sewers on the pavements. It almost seemed ordinary now.

Two events alone remained in my memory long after this last view of Delhi had passed. The first was when an angry old Sikh nabbed two young thieves in the act of robbing the till of his restaurant next door. Both of the youths were also Sikhs, but this didn’t stop the old man whacking them round the head with a large club. It also didn’t stop the typical curious crowd of onlookers gathering from miles around to watch. But were the young reprobates repentant of their crime? None of it. They just rubbed their cracked heads and grinned and giggled like naughty children who enjoyed the attention and who would doubtless repeat the offence at the earliest possible opportunity. Even when a couple of passing policemen on a motorbike chopped them down with well-aimed lathi blows to the back of the knees, they showed no remorse, but simply got up and strolled off laughing.

And the second was the sight of a dazed young Westerner staggering down the street below us. Like many long-stay backpackers in India, he had sustained an injury, and wore a dirty bandage round his wrist. He was also doped up to his eyeballs. So much so indeed, that he had no control over his movements and simply tottered up and down the dark road bumping into Indian pedestrians.

My final trip with the girls was to the Connaught Place bus-rank, which ran a late-night service to Delhi airport. Somehow, all three of us (together with my luggage) managed to squeeze into a single cycle-rickshaw. The ride was remarkable in that it restored my faith in Indian rickshaw drivers. The young cyclist made no complaints the whole way, despite his very heavy load. He made no demands for black-market business, just smiled and got on with his job. I was so impressed with him that when he asked me for two rupees at the bus-rank, I gave him ten. Caught completely by surprise as this vast sum (actually less than £1), he gave the note a big kiss and beamed us a smile of eternal gratitude.

I paid my farewells to Megan and Jenny over a cup of coffee in the quiet Palace Restaurant, near the bus-rank. We were the last three guests of the day, and the waiters hovered around us anxiously, waiting for us to leave and let them go to bed. This last restaurant I visited in India, somewhat appropriately, turned out to have the most deliciously mis-spelt menu – including mouth-watering specialities like CHICKEN MARRY LAND, CHICKEN STRONGOFF, BRAIN CURRY, BOMBOO SHOOT and CHICKEN GOBLET. The ‘piece de resistance’, to our mind, was however a Chinese dish called FRIED WANTON. And not only could you have your ‘wanton’ fried, but any which way you wanted her – including WANTON, VEG OR NON-VEG, or WANTON, ONE PLATE, or even WANTON AND CHIPS!