Chapter 5

Mussel Memory

Doing science with awe and humility is a powerful act of reciprocity with the more-than-human world.

Robin Wall Kimmerer

Tell almost anyone that you’re working with freshwater mussels, and they will leap to culinary conclusions. Whether at a family reunion, a bar, or a boat ramp, people will picture your unionids as the distantly related marine mussels appearing in delicious sauces. They will furrow their brow or wrinkle their nose or grin expectantly and ask the question posed to all mussel biologists: “Can you eat ’em?”

It’s a valid question, worth investigating. Kentucky-based mussel biologist Wendell Haag informally polled people for years about eating mussels. As he encountered locals while doing field research, he turned the commonly asked question backward: “Do you eat ’em?” In twenty-five years, Haag describes in his book, he “received only one positive response, from a grizzled old-timer way out in the woods who assured me that he eats them ‘all the time.’” Later, when Haag was writing North American Freshwater Mussels—an excellent science and history read that deeply explores everything about these mussels—he decided that his research was incomplete. He had never actually eaten a freshwater mussel.

Haag had always been an outdoorsy kid, which led him to his first mussel encounter. When he was ten years old, his family went camping along the Red River in Kentucky, near his home. “While wading in the river, I stumbled onto a bed of freshwater mussels,” Haag recounts in his book. “I was stunned. I thought shells could only be found at the faraway ocean and had no idea such exotic gems lived in my own neighborhood.”

With a vague notion that he wanted to become some kind of biologist, Haag headed to Eastern Kentucky University. Since his Red River moment as a boy, Haag had cherished a fascination with these mysterious animals that lived in the river bottom. Haag’s early relationship with mussels occupied the late hours and long miles characteristic of a new passion. During his last year in college, he would throw a loaf of bread and hunk of cheese in his car on Friday afternoon, drive into the darkness, hours from home, and sleep on the ground somewhere. Saturday morning, he’d wake up and spend the entire day snorkeling a river and then sleep on the ground again. After staying in the river until dark on Sunday, Haag would climb back in his car and drive through the night to get back for classes on Monday. He did this every weekend. Mussels’ life history was still mostly uninvestigated in the mid-1980s, so opportunities to study them were wide open. Wendell Haag had found his niche.

For years, I carried in my head a formidable image of Haag. A US Fish and Wildlife Service biologist, he proliferates published scientific articles. He collaborated with Jim Stoeckel and Andrew on various research projects and served on the academic committee for Andrew’s PhD. Haag, self-described as a Draconian editor, slashed Andrew’s drafts of scientific papers and provided an especially rigorous portion of the written exams Andrew was required to complete for his PhD.

When I finally met him in person, Haag’s soft-spoken demeanor caught me off guard. He has a compact build and tousled brown hair above large round glasses. He plays the guitar and sings in a band called the Okratones. Haag loves doing research, but for fun he’d rather go out with no clipboard, no instruments, no measurements, no agenda, and just see what he finds. His interests have diversified since his college days, but he’s still that kid who gets a thrill when he visits a river and finds a mussel: “It’s like seeing an old friend.”

Determined to truly understand these old friends, Haag—accompanied by his intrepid wife and a coworker—eventually tasted them. They cooked up a sampling of freshwater mussels, including Asian clams, species of Quadrula, species of Lampsilis, and Obliquaria reflexa—the three-horned wartyback. They fried some. They boiled some. They roasted some. They made some cocktail sauce to lubricate the eating process but otherwise adhered to their goal of assessing the mussels’ flavor and ate them unadorned.

In modern Western cultures, humans have not consumed freshwater mussels with much regularity or much relish. Some cultural stigma against eating these river- bottom dwellers seems to contribute to their absence from our menus. Stigma aside, however, this aversion may exist because freshwater mussels are said to contain a disproportionate amount of putrescine, a chemical characteristic of decaying animal tissue.

Haag noted that when he ate them, the smaller mussels, including the Asian clams, were actually quite tender but almost completely lacked flavor. Feeling adventuresome, the wartyback-eating Haags tried some more hefty unionid mussels, which were a different story. “They were very tough and had an odd and disagreeable taste,” Haag reported in his book, adding, “maybe this was the putrescine.” Overall, Haag concluded, mussels taste like they smell—peculiar and pungent. While the taste testers didn’t actually become ill from eating the mussels, Haag noted, “the unpleasant memory of the flavor stayed with me for several days.”

Wendell Haag and Andrew and I belong to a group of newcomers on the freshwater mussel scene. Long before anyone donned wet suits to study mussels, humans in North America consumed mussels as a supplementary food source and used their shells as early as ten thousand years ago. Excavated piles of discarded shells, called middens, contain large mussel shells, some fashioned into hoes and scrapers. In the Choctaw Nation—now in Oklahoma—artists carved some shells into spoons or finely made jewelry. Another practice involved burning mussel shells and then crushing them into tiny flakes that, when incorporated into clay, strengthened the Choctaws’ pottery.

These often-massive middens, however, mostly hold smaller, uncarved mussel shells, discarded after people ate the animal inside. Haag suspects that Native people avoided eating larger, tougher mussels and may have had ways of preparing mussels that improved their flavor and digestibility. “I’ll bet you could eat them fine if you got used to them,” he told me. “Especially if you were hungry.” Another possibility—given the decline of water quality and mussels’ embodiment of that water—is that mussels simply used to taste better. Native people’s use of freshwater mussels—for food or tools or art—speaks of an intimacy with creeks and rivers. A perception of subtleties and knowledge of the creek bottom must accompany a reliance on mussels for their meat or shells, especially when harvesting in moderation to preserve a steady supply.

Lacking sufficient hunger or Haag’s gastric courage, I have never cooked or tasted freshwater mussels. While living in the South, I managed to never get around to it. Eventually, I regretted missing that opportunity. Just months after we ultimately left the South and its wealth of mussels, I discussed eating mussels with newly five-year-old Sam, over a bowl of clam chowder. “I always kind of wanted to try eating mussels,” I said. “I’ll bet we could make some good mussel chowder.”

“No. We couldn’t do that,” Sam said, eyes round.

“Why?”

“Because mussels are part of the Earth!”

“Oh.”

“And to make mussel chowder, you’d have to kill them,” he added, scandalized, despite his status as an informed omnivore who delights when he has pig or deer on his plate. He leaned toward me, “You wouldn’t want to kill your favorite animals, would you?”

My favorite animals, being soft bodied, can’t live without their most salient features—hard shells—and their shells, unlike their meat, have continued to attract humans throughout recent history. Mussels don’t occupy previously existing shells like hermit crabs. Neither do they perform successive molts like crayfish do as their innards outgrow a hard exterior. Instead, mussels build their shells around themselves like snails. A mussel secretes its shell from the thin tissue called a mantle, wrapped like a cloak around the organs. As mussels mature, calcium carbonate joins material called chitin—the tough yet flimsy stuff of insects’ exterior skeletons—to form a harder composite material. This hard material is what once made mussel shells useful for tools and later lured early naturalists to collect the shells. The fascinating shell shapes also earned mussels their descriptive names, such as elktoe, rabbitsfoot, and pistolgrip.

A mussel grows at the outer edge, laying down curved rings of shell to slowly expand from lentil size to mature mussel size, which can range from the size of your thumb to the size of your face. Mussels grow their shells in layers, adding regular growth rings. Remarkably, they can live for decades, with a few species reaching one hundred years old or more. Cross sections of a shell reveal close estimates of a mussel’s age, although recent evidence suggests that mussels might not create a growth ring every year. If this is true, counting rings could underestimate mussel age, meaning that some mussels might be hundreds of years old.

Once, holding a mussel in my palm, I curled my hands around the shell, covering the outer half. What remained uncovered was an image of the mussel’s younger self, what she looked like maybe thirty years ago. At the edge of this smaller version was a defect, visible as a divot in that growth ring on both halves of the shell. Something had gouged the front edge of the mussel that year.

Mussels sketch a history into the most durable part of themselves. The rings etch into the outermost layer of the mussels’ three-layer shells, which is most often black or brown, sometimes with earthy yellow, green, or reddish colors. We can read clues about the years encoded into these shells, decades of river stories recorded in calcium carbonate. Wendell Haag, among others, has studied these growth rings, carefully cross dating by comparing one mussel’s rings to other mussels in the same and other rivers. He found parallels in growth rings among mussels and can even identify specific years on the shells and match them—cross-dating techniques also used by tree scientists. His findings suggest that mussels’ rings respond to large environmental influences, especially stream flow. Like the rings of tree trunks, turtle shells, and fish ear bones, mussel shells are a map of time. Through time, their shells have also been mussels’ downfall, drawing the attention of humans, whose infatuations with these shells killed many mussels.

Hiding inside a mussel’s record of the past, the shell’s most startling layer—the nacre—coats the shell interior. Mussel nacre is the stuff of pearls. Luminous and delicately hued, the nacre ranges from white to pale pink to barely lavender to deep purple. The nacre makes you want to evert the shell to display the mussel’s inner splendor, but because opening them wide kills them, we can only admire the nacre of dead mussels. On the shell of a freshly dead mussel, the nacre still shimmers brightly, but it dulls with time spent in the creek. If you want a pearly shell specimen, you must either collect a freshly dead mussel, or kill the mussel and remove the soft body from the shell. Outside the creek, and without the mussel, this nacre can endure exquisitely as shell specimens, pearls, and pearl buttons. These gleaming, durable items caught the eye of humans with an insatiable appetite for more than food or tools.

Like certain oysters, freshwater mussels can make pearls. Their mantle exudes extra nacre to surround a speck of irritating foreign material, including certain parasites, just inside their shell. Freshwater mussel pearls are typically small and oddly shaped, lacking value. It is rare to find a large or uniform pearl in mussels, such as the one that triggered a pearl rush when a carpenter in New Jersey stumbled upon a ninety-three-grain pearl in 1857. The rarity of this find only enhanced its value and fueled pearl hunters’ imaginations. Over the next forty years, crowds flocked to creeks and rivers, swarming on banks and sandbars to snatch up bivalved treasure chests.

Then-abundant mussel populations, which flourished in the still-healthy streams, shrank under the onslaught of pearl prospectors, who chased glimmering illusions of fast money. Prospectors inundated a promising mussel stream and rapidly depleted the mussels, making pearl harvest “a wildly unsustainable endeavor,” as Wendell Haag writes in North American Freshwater Mussels. When a stream’s mussel supply faded, the rush shifted elsewhere, spreading from the Northeast to places like Arkansas, Wisconsin, Tennessee, Louisiana, and Texas. By 1900, the pearl fishery folded, but a new mussel craze had taken hold.

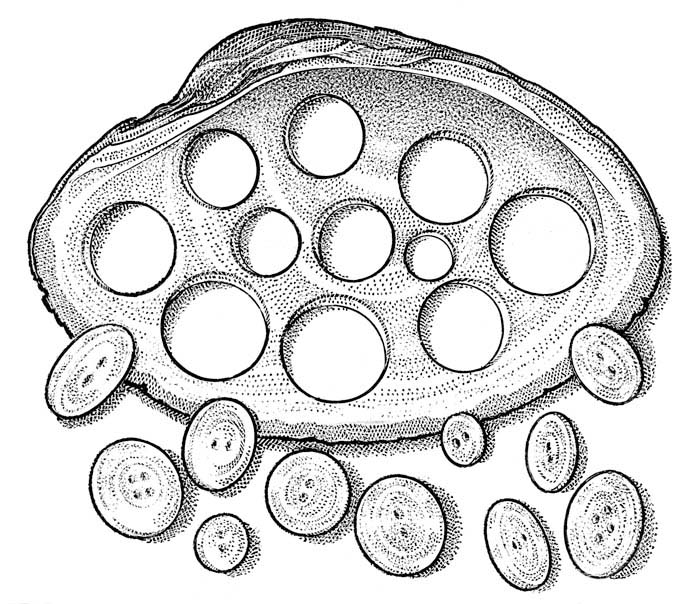

As pearl hunters were following reports of mussel populations across the country, they typically pried open a mussel, looked for pearls, and then tossed aside the seemingly worthless shell. In the 1890s, however, those shells got a new reputation. During a snapshot of time, created by a seventy-five-year blaze of industry, freshwater mussel shells appeared on clothing. More precisely, pearly circles of polished nacre served as buttons, holding almost everyone’s clothes together. The mussels whose shell bits fastened so many garments once lived in the Mississippi River, the Alabama River, and elsewhere, harvested by the thousands for their shells.

A determined innovator named Johann Boepple, experienced at making buttons in Germany, immigrated to Illinois hoping to replace pricey imported raw button materials with local shells. He worked as a laborer and found his first mussel bed in the Sangamon River by cutting his foot on a shell. Boepple then began tinkering with making freshwater shell buttons in his spare time; he developed equipment and techniques for manufacturing buttons and made possible the North American freshwater mussel pearl button industry. He searched for just the right mussel shells—not too thin shelled, large enough for hole- punching, with superior nacre quality and abundant populations. For these reasons, the pearl industry preferred the yellow sandshell (Lampsilis teres) and the ebonyshell (Reginaia ebena), among others.

In 1891, Boepple opened the world’s first pearl button plant, and mussels rapidly became buttons. The industry grew beyond Boepple, whose aversion to mass production limited his button making. In factories mostly located in Muscatine, Iowa, circular saws punched pearl buttons from mussel shells. Muscatine, a small town whose main streets hug a wide curve of the Mississippi River, became the heart of the button industry. Visit Muscatine today and you can shop in the renovated historic downtown, called Pearl Plaza. You can eat at the Button Factory Woodfire Grille, formerly the Ronda Button Company. Or you can tour the Muscatine History and Industry Center to trace the rise and fall of pearl buttons.

Punched-out mussel shell with pearl buttons

At its peak, this impressive industry relied heavily on large mussel beds in rivers of at least twenty-two states, throughout the Midwest and into the Southeast. Thousands of people found work harvesting mussels for buttons. These shellers often lived in riverside or houseboat communities and could sell mussels as fast as they could harvest them.

Shellers collected mussels with long tongs and rakes. They also snagged mussels by taking advantage of the mussels’ reflexive closure when something poked into their slightly open shell. Several setups worked in similar ways. The crowfoot involved a bar with ropes that held hooks to snag the mussels. Brail boats employed brails—poles or boards that dangled short chains ending in hooks tipped with small beads. The boat dragged the brail along the bottom, and mussels clamped onto the beads. Other mussel hunters dove to the bottom, with or without a surface-air supply line.

In those days of abundant mussels and little regard for preserving habitat or sustainable populations, capturing mussels seemed to require less subtlety and aperture identification than our searches today. Collecting large numbers of mussels from big rivers with no intention of nesting them back into place clearly expedited the process. Mussel harvest for pearls peaked in 1916 but continued into the 1940s, significantly depleting many native mussel populations in large rivers. Some mussel species have since rebounded, after harvesting pressure stopped, just as some populations of crocodiles recovered from depletion after hunting for their skins decreased. In most places, mussel harvest missed just enough individuals to later reestablish a mussel bed. For both mussels and crocodiles, however, habitat destruction became a daunting hurdle for recovering populations.

Johann Boepple reportedly met his demise in a sadly ironic twist of bad mollusk karma. He cut his foot by stepping on a sharp mussel shell, the pink heelsplitter, Potamilus alatus—named for its wing that protrudes from the shell edge like a blade. Boepple died in 1912 of a subsequent wound infection. The pearl button industry died too, struck down by overexploitation of mussel shells, the invention and mass production of plastic buttons, and the increasing popularity of zippers.

Another multimillion-dollar mussel harvesting purpose arose: farmed pearls. This time, freshwater mussel fragments prompted oysters to form pearls. At the center of nearly every farmed pearl is a nugget of organic material, which stimulates the oyster to produce the pearl. The pearl industry found best results when using a small sphere of freshwater mussel nacre. The demand for mussel nacre in this industry, too, is now nearly obsolete, replaced with other materials.

Freshwater mussel harvest has mostly become a thing of the past. Scientists are finding that we can reap the benefits of mussels by increasing, not decreasing, their numbers and diversity in rivers. As we learn about river health and its relevance to our tenuous water supply, native freshwater mussels emerge as valuable for reasons that do not require us to destroy them.

Before our twentieth-century assaults on creeks and rivers through dams, pollution, channel erosion, and dewatering, mussels flourished. They thrived for many centuries, even while harvested by Native Americans. When the pearl rush and button industry began, rivers generally flowed unimpeded. Among the people who frequented creeks and rivers, noticing and documenting these mussels, were naturalists with skills and dedication ranging from those of a scientist to those of a dilettante. These were people who liked poking around in nature, taking away interesting things, and describing—often in excellent detail—what they found.

These early naturalists identified and studied freshwater mussels by their shells. They often called themselves conchologists. Upon collecting a mussel, the naturalist typically shucked out the animal itself and preserved the shell. Through most of the nineteenth century, these naturalists collected and named mussel species like kids grabbing candy under an open piñata. Shells were attractive specimens, easy to find and transport, lovely to display. Study of mussel biology and ecology came later. Taxonomy grew wild branching vines, fertilized by a passion for discovery. Mussels were named for their shell morphology, resulting in entertaining names—fuzzy pigtoe, orangefoot pimpleback, sheepnose, and three-horned wartyback—and some name duplications that have since caused taxonomic head-scratching. Surprisingly, many species descriptions are still recognized and even supported by genetic evidence.

Two prominent men describing mussels in the early 1800s were Philadelphia-based natural historians, Isaac Lea and Timothy Abbott Conrad. They were rivals more than colleagues and each man sparred to describe new species first. Conrad and Lea published furiously, each criticizing the other to elbow him out of scientific favor. Similarly, the eccentric naturalist Constantine Samuel Rafinesque attempted to rival his contemporary, Thomas Say, a meticulous observer. The exquisite color plates—mostly illustrated by his wife, artist, and scientific collaborator, Lucy Say—published in Thomas Say’s book, American Conchology, outshined Rafinesque’s rough sketches.

Other naturalists continued the work of describing mussel species. Several publications paved the way for detailing mussel fauna, including Synopsis of the Naiades, or Pearly Fresh-Water Mussels, by Charles Torrey Simpson. Until the mid-twentieth century, naturalists called freshwater mussels by this more poetic name, naiades, after those mythological freshwater nymphs whose lives can’t be separated from their particular creek or river. Having only a whisker of knowledge about mussel ecology, early naturalists named them with an essential accuracy.

As the twentieth century began, mollusk experts shifted from the previous conchologists to mussel biologists. They started studying the animal inside the shell. Intense mussel harvest for pearls and buttons spawned both concern for their decreasing numbers and a resulting interest in studying and propagating mussels, in part to renew the supply of mussels for harvest. In the early 1900s, taxonomists like Arnold Ortmann, who is considered the father of modern mussel ecology, analyzed mussel reproduction and theorized about why mussels live where they do, topics still being studied.

In 1910, the first large-scale mussel research began along the Mississippi River at the Fairport Biological Station in Iowa. For two years, the button maker Johann Boepple himself served as the station’s commercial shell expert and surveyed mussel beds in rivers. Using early naturalists’ shell collections and observations as a springboard, modern scientists began a trajectory of studying mussel biology and life history that continues to reveal new discoveries today.

In 2008, three notable mussel scientists published Freshwater Mussels of Alabama and the Mobile Basin in Georgia, Mississippi, and Tennessee, a book of nearly biblical significance to mussel biologists in the region. Retired US Fish and Wildlife biologist Jim Williams, who still leads mussel identification workshops and publishes scientific studies, teamed up to write the book with Alabama state mussel biologist Jeff Garner and Arthur Bogan, curator at the North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences. In contrast to this thick book’s section on early mussel studies, which features only a few pioneering individuals, the section describing recent decades of mussel research is dense with names.

As Wendell Haag writes in North American Freshwater Mussels, “This explosion of interest in freshwater mussels illustrates the curious potency of the mussel bug that has bitten unwitting naturalists for hundreds of years.” Those of us bitten by that mussel bug plunge into learning about these exquisite, vulnerable creatures, traveling widely and getting very wet in search of them. If our guard is down, we can spout embarrassingly fervent monologues about their pretty shells, their complex lives, their benthic habitats, and their plight.

“To those individuals who have never worked with unionoid mussels,” Freshwater Mussels of Alabama acknowledges, “these animals may appear to be about as boring as any organism could possibly be. After all, they have no head and only one foot and spend most of their lives in the bottom of a stream or lake with only their posterior ends exposed.”

But those individuals who have worked with native mussels rapidly develop an almost reverent affection for these animals. Mussel scientists can recite Latin names and identifying characteristics for hundreds of mussel species. They also carry mussel habitat and distribution maps in their heads. They know creeks and rivers the way a deeply religious person knows sacred texts. They speak in a language of watersheds, dropping creek names and referring to shoals, sandbars, dams, and geologic features as if quoting chapters and verses. At the mention of a particular bridge crossing, these people can describe riffles and pools, feel the creekbed under their feet and hands, and discuss which mollusk species might be present or extinct there. Many of these mussel lovers belong to the Freshwater Mollusk Conservation Society, known by its members as the FMCS.

Across the continent—and the world—people who love mollusks pursue mussels. At the 2013 FMCS meeting, held along the dammed Tennessee River in northern Alabama, I soaked in the details and photos of their dedication. Dry-suited Canadians stood up to their thighs in a snowy river; Alabama biologists dove in shimmering summer heat. In one photo, grinning people with thumbs-up gestures knelt on a sandbar beside a flowing stream and piles of mussels. One photo showed a University of Oklahoma graduate student with a deep frown and thumbs-down, straddling a drought-dried research site, where her research expired with the mussels.

In laboratories, biologists held syringes, squirting things in or drawing things out between partially open mussel shells. Missouri-based biologist Chris Barnhart—collector extraordinaire of mussel images and videos—showed microscope photos where larval glochidia lay agape or clung in bubble-like cysts on sections of fish gills. Preserved slices of mussel muscle tissue on microscope slides reminded me of veterinary school and inspired bad puns, such as “check out my mussels.” Experiments or breeding programs in labs worked to keep mussels alive in captivity. Biologists rigged up experimental equipment of their own design, using aquaria, tanks, ponds, coolers, hoses, and PVC plumbing, often on a shoestring, or they sometimes used high-tech commercial gear to conduct experiments. Environmental engineer Craig Just—based in Iowa, where, he joked, the fertilizer-containing water is extra nutritious—employed sensitive equipment to measure mussels’ effects on nitrogen in the water.

Mollusk lovers seem to carry a different kind of vision and memory. They can see mussels hidden in rivers. They remember what the rivers used to be. A person who studies river-bottom animals can envision the Tennessee River’s ancient bends and shoals and the still-accumulating sediment that blankets the reservoir’s bottom. They can see into the pas, and picture the wild river. They grieve that river, which was once home to nearly seventy species of freshwater mussels.

The Upper Mississippi River, mussel biologists can tell you, was historically home to forty species of mussels. By 1900, most of the mussels were gone, primarily due to extreme pollution in the nineteenth century. With improved water quality, thanks to industry changes and better handling of sewage overflow in Minnesota’s Twin Cities, almost twenty species returned on their own.

The Higgins eye pearlymussel, Lampsilis higginsii, however, still hovered near extinction. The species suffered dramatically under the onslaught of invasive zebra mussels, which crowded onto native mussels, crippling and suffocating them. As in many rivers, the US Army Corps of Engineers maintained a nine-foot navigation channel for boat traffic through the Upper Mississippi. This channel, made by dredging the river bottom, damaged habitat for native mussels that nestled into river bottoms but facilitated movement of zebra mussels, which clung onto boats, further endangering the Higgins eye pearlymussel. Mussel lovers’ hearts clench at this type of onslaught.

So biologists and other mussel lovers began a project to save the endangered Higgins eye in the Upper Mississippi Basin. They were helping to usher in a new era of our relationship with mussels, one where cooperation among scientists, government, industry, and concerned citizens will determine these animals’ survival and the health of our rivers. One of the project leaders, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources biologist Mike Davis, has a lightly grizzled chin and a relaxed way of talking with his arms. He laughs ruefully about how he got hooked on mussels. “It’s a bad story,” he tells me.

Decades ago, Davis started his career as a commercial fisherman. When the price per pound of freshwater mussel shell exceeded the price of fish, he and his buddy switched to mussels. They got a homemade hookah rig that used an air compressor connected to part of a car air conditioner. Mussel hunters—both scientists and harvesters—have used these rigs, and more sophisticated variations of them, to provide surface air to a diver through a long tube, allowing the person to remain at river bottom without an air tank, or scuba gear. This hookah rig’s small engine and the rest of the contraption were screwed onto a piece of plywood. The problem was, Davis recalls, that the air intake was right next to the engine exhaust. If the wind was blowing right, you could taste the exhaust. They fixed that part right away.

Using this refurbished hookah rig as a surface-air supply, Davis dove into the Mississippi River for mussels. One summer of mussel harvest sparked his interest in the diverse mussels he found. Curious, he started reading about them and was eventually compelled to return to college after a fifteen-year absence. After he graduated, Davis took a job at the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, where he has worked ever since. As a fisherman, he never guessed that he would eventually work to restore the river and mussels that he had once harvested to support his livelihood.

With funding from the Army Corps of Engineers, the Higgins eye mussel project leaders found their starting point a bit awkward. First, they needed the Corps to stop dredging the navigation channel. After negotiations succeeded in changing the dredging, the next step was to reintroduce Higgins eye mussels to the Mississippi River.

Preparing for reintroduction, the team began propagating Higgins eye pearlymussels, very carefully. At the propagation facility, they used syringes to gently extract larval mussels from brooding females. Then they squirted those larvae directly onto fish gills, inoculating the fish with these mussel hitchhikers. Volunteers stood side by side like a bucket brigade, inoculating fish by hand, working to douse the fire of extinction. After two weeks, they collected juvenile Higgins eyes as the offspring dropped off the fish. Then they released the juveniles into the wild. It didn’t work.

The team ultimately tried multiple methods of reintroduction. They inoculated fish with mussel larvae on-site, along the river, and then released larvae-infested fish straight back into the Mississippi. With luck, the larvae would transform into juveniles and drop from the fish in opportune locations. The success of this technique proved difficult to monitor, as the Mississippi River is a big place to hunt for new beds of baby mussels.

The scientists tried placing larvae-infested fish in big cages in the river, limiting the distribution of juvenile mussel nurseries. It didn’t work. They tried stocking young adult Higgins eye pearlymussels—forty-three thousand of them, which looked like a pile of lentils—in specific sites. A crew in wet suits distributed them on the river bottom in a grid pattern for easy monitoring but returned to find many mussel shells munched and broken open. Apparently, grouping the mussels in a grid formed a nice buffet for mussel predators. After that, the team tried standing on the boat and scattering the juvenile mussels more randomly, like wedding guests tossing rice. Still no luck.

The scientists finally tried placing the juvenile mussels themselves into a closed cage in the river. They returned the first year to find only three tiny living mussels, which they named Larry, Moe, and Curly. The next year, however, Larry, Moe, and Curly had grown respectably. They later found new little recruits.

This process of propagation and reintroduction is a precarious one, requiring more delicacy and teamwork than mussel harvests or studies of the past. So many people, shoulder to shoulder, agonized over these specks of mussel for many hours across many seasons. Each mussel itself was like a whooping crane chick parented by biologists, coaxed and carried to safe habitat. Hearing their failures and long-awaited successes described at the level of individual mussels surprised me. As a veterinarian, I work to save individual lives, but ecology—I previously assumed—looked only at populations and systems. The ecology of extinction, like most emergency measures, seemed to depart from the ordinary.

On the Upper Mississippi, the team’s efforts began to succeed. The Higgins eye pearlymussel population started to wobble ahead on its own, a kid on a bicycle when the parental hand first lets go. The scientists began to find gravid females. After four growing seasons, half of the female mussels were brooding larvae. They even observed some natural genetic variation emerging, as evidenced by variation in shell color. “If your mussels come in red, green, and yellow, and you get back red, green, and yellow mussels,” Mike Davis notes playfully, “you’re doing something right.”