1862

White Dwarfs

Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (1784–1846), Alvan Clark (1804–1887), Alvan Graham Clark (1832–1897)

The second half of the nineteenth century saw the design, manufacture, and operation of larger and higher-quality telescopes by skilled astronomers and instrument makers such as William Lassell in England and Alvan Clark in America. Clark’s specialty was designing and grinding large glass refracting lenses that could be combined to yield high angular resolution and achromatic performance—free of the colored rainbow and halo artifacts that plagued many large lenses in previous refractor designs. Alvan Clark and Sons, telescope makers of Massachusetts, gained a worldwide reputation for high-quality instruments, many of which are still in operation today.

One of those Clark sons was Alvan Graham Clark, who often tested the company’s new lenses on his own astronomical research. On one such occasion, observing on January 31, 1862, from the outskirts of Boston, the younger Clark trained a new 18.5-inch (47-centimeter) refracting telescope on the bright, nearby star Sirius. In 1844 the German mathematician Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel had predicted that the bright stars Sirius and Procyon had Proper Motion changes that were caused by unseen companions. The superbly clear night and the excellent quality of the lenses enabled Clark to discover that faint companion to Sirius, now known as Sirius B.

By the early twentieth century, Sirius B was found to have a spectrum similar to Sirius itself, even though it is much fainter. It and a few other visually dim stars were soon recognized to be part of a new class of small, hot stars dubbed white dwarfs. White dwarfs are now known to be a common end result of low-mass, Sun-like stars that have run out of hydrogen fuel but are too small to have exploded into supernovas.

By analyzing their orbits and using Kepler’s Laws, white dwarfs like Sirius B have been found to be extremely dense—packing anywhere from 0.5 to 1.3 times the mass of the Sun into a volume the size of the Earth, for a density of more than 1,000,000 grams per cubic centimeter! As such, white dwarf stars are members of a special club of compact objects, also including neutron stars and black holes, that have the highest known densities of anything in the universe.

SEE ALSO Three Laws of Planetary Motion (1619), Mizar-Alcor Sextuple System (1650), Proper Motion of Stars (1718), Stellar Parallax (1838), Neutron Stars (1933), Black Holes (1965).

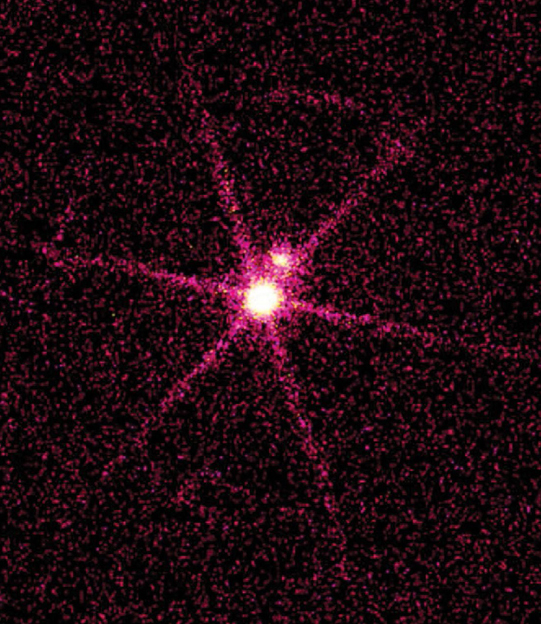

NASA Chandra Observatory X-ray image of the nearby star Sirius and its white dwarf companion, Sirius B. Sirius B is the brighter star in this image; with a surface temperature of 25,000 kelvins, it is a prodigious emitter of X-rays. In visible-wavelength light, Sirius B is actually 10,000 times dimmer than Sirius.