1906

Mars and Its Canals

Giovanni Schiaparelli (1835–1910), Percival Lowell (1855–1916)

The Martian moons Phobos and Deimos were discovered during the opposition of 1877 partially because it was an excellent and relatively rare closer-than-normal alignment between Earth and Mars. Others took advantage of the opportunity to focus on Mars itself, including the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, who created numerous maps in which he gave the planet’s “seas” (darker areas) and “continents” (brighter areas) historical Latin and Mediterranean names. He also observed fine, dark, linear features on the planet that he thought might be channels of some kind. The Italian word for “channels,” canali, was widely mistranslated into English as “canals.”

The Massachusetts industrialist, author, and astronomy enthusiast Percival Lowell became smitten with Schiaparelli’s and others’ descriptions of such linear features on Mars, and was convinced that higher-quality observations could reveal the features in more detail. In 1894 he used part of his personal family fortune to found a high-altitude observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, and to equip it with a 24-inch (61-centimeter) Alvan Clark and Sons refracting telescope. Lowell Observatory quickly became one of the world’s premier centers for astronomical research, and Lowell himself focused much of his own observing time on detailed observations and drawings of Mars.

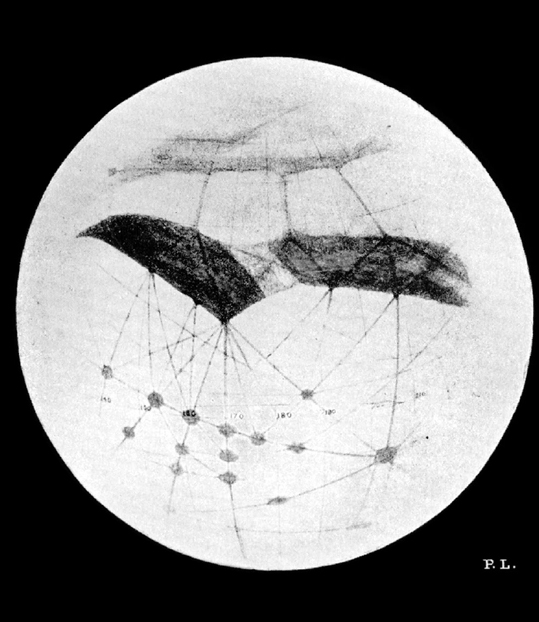

To Lowell’s eyes, Mars was crisscrossed by intricate networks of dark linear markings that could only be the work of an intelligent species. In his popular 1906 book, Mars and Its Canals, he imagined that these were alien waterways designed to bring meltwater from the polar caps down to the great equatorial cities of the Red Planet. The idea that Mars was inhabited by a race of highly skilled engineers was widely popularized.

A photograph of Percival Lowell, from around 1895.

Modern photography and space missions have showed that Schiaparelli’s and Lowell’s canals were likely just an optical illusion. But public (and scientific) fascination with Mars as a potential abode of life has remained just as strong.

SEE ALSO Mars (c. 4.5 Billion BCE), Phobos (1877), Deimos (1877), First Mars Orbiters (1971), Vikings on Mars (1976), First Rover on Mars (1997), Mars Global Surveyor (1997), Spirit and Opportunity on Mars (2004), First Humans on Mars? (~2035–2050).

One of Percival Lowell’s sketches of Mars from around 1900, showing examples of the fine, linear markings that he and some others interpreted as evidence of a large-scale network of irrigation channels on Mars. Through his work, Lowell did much to popularize the idea of life on the Red Planet.