1930

Discovery of Pluto

Clyde Tombaugh (1906–1997), Percival Lowell (1855–1916), William Henry Pickering (1858–1938)

The 1846 discovery of Neptune was enabled by French mathematician Urbain LeVerrier’s calculations of the likely position of a planetary-mass object that was causing variations in the orbit of Uranus. Subsequent observations of Uranus and Neptune led some astronomers to speculate that Neptune was not responsible for all the discrepancies in Uranus’s orbit—there could still be an Earth-size planet lurking way out there.

One of the astronomers who believed in this “Planet X” was Percival Lowell, the New England businessman who had founded Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, in 1894. Both he and the American astronomer William Henry Pickering generated predictions for where Planet X might be found. An unsuccessful search was carried out from Flagstaff from 1909 until Lowell’s death in 1916, when the search was put on hold during a battle over Lowell’s estate. Pickering’s own 1919 search also failed.

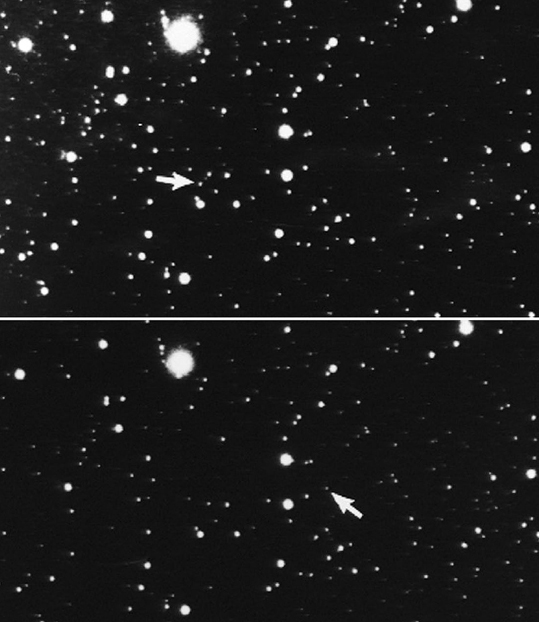

The search in Flagstaff resumed in 1929 and was placed in the hands of 23-year-old Clyde Tombaugh, a new staff member who had impressed Lowell Observatory director Vesto Slipher by sharing with Slipher the observations and sketches he made while growing up in Kansas. Tombaugh used Lowell’s 13-inch (33-centimeter) astrograph (a telescope designed to work with large photographic plates) to survey the expected regions of the sky for objects moving at the right trans-Neptunian rate. After almost a year’s effort, on February 18, 1930, he found a small, new world in the right place. A British girl won a subsequent naming contest by choosing the moniker Pluto, after the Roman god of the underworld. Ironically, modern reanalysis of the orbit of Uranus showed that there was no discrepancy beyond that which Neptune could explain; Tombaugh’s discovery of Planet X was pure skill and coincidence.

Nonetheless, for more than 75 years Pluto was the solar system’s ninth planet, orbiting out near 40 astronomical units, and now known to have five moons (one, Charon, relatively large). In the 1990s, however, it became clear that Pluto is simply one of the largest of the small icy worlds in the Kuiper Belt. In 2006, the ninth planet was controversially and unceremoniously demoted to “dwarf planet” status.

SEE ALSO Pluto and the Kuiper Belt (c. 4.5 Billion BCE), Discovery of Neptune (1846), Triton (1846), Charon (1978), Kuiper Belt Objects (1992), Demotion of Pluto (2006), Pluto Revealed! (2015).

Clyde Tombaugh’s original Pluto discovery plates from his photos taken at Lowell Observatory on January 23 (top) and January 29 (bottom), 1930. Pluto is indicated by the white arrow in each plate.