1939

Nuclear Fusion

Hans Bethe (1906–2005), Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker (1912–2007)

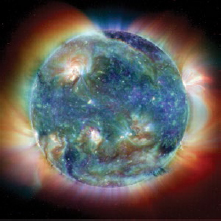

While some of the major characteristics of stellar interiors—including their extremely high pressures and temperatures—had been worked out empirically by astrophysicists such as Arthur Stanley Eddington in the 1920s, substantial uncertainties remained about just how stars generated their energy. Eddington had thought about the possibility that nuclear fusion (the fusing of lighter elements into heavier ones, with the release of energy in the process) might power stars like the Sun. But this was only speculation, based partly on early nuclear transmutation experiments (the conversion of one element to another) by Ernest Rutherford and others.

Physicists soon had the means to work out and test theories for energy generation in stars in more detail, however. Among the pioneers in this field were the German physicist Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker and the German-American nuclear physicist Hans Bethe. Between about 1937 and 1939, Bethe (in the United States) and Weizsäcker (in Germany) worked out the details of the ways that hydrogen atoms could be fused into helium at the extreme conditions near the centers of stars. Bethe’s 1939 paper, “Energy Production in Stars,” described the specific nuclear chain reactions that were likely at work in the interiors of average-mass stars like the Sun, as well as in high-mass stars.

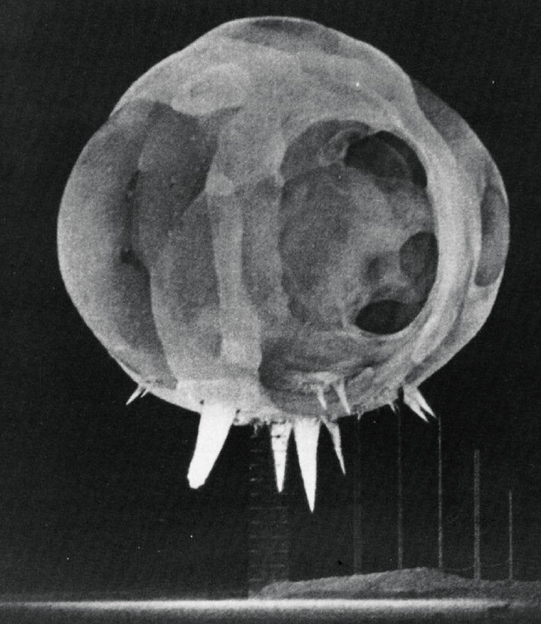

As exciting as these discoveries were scientifically, Weizsäcker, Bethe, and their colleagues knew that the nuclear genie was out of the bottle. Some nuclear synthesis chain reactions based on the same physics as reactions inside the stars could also be created artificially, releasing enormous amounts of energy. As World War II broke out, both the American and German governments set their physicists at work on the weaponization of nuclear fusion. The US effort was dubbed the Manhattan Project and involved Bethe as a leading theorist; it led to the development and detonation of the atomic bombs that ended the war, as well as the hydrogen bombs that began the long Cold War that followed.

SEE ALSO Radioactivity (1896), Eddington’s Mass-Luminosity Relation (1924), Neutrino Astronomy (1956).

The direct result of figuring out the details of how energy is generated by nuclear fusion in stars like the Sun (inset, in an extreme ultraviolet color composite from the NASA and ESA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, or SOHO, satellite) was the development of nuclear fusion weapons. This eerie nuclear fireball photograph was taken about one millisecond after the detonation of a nuclear bomb test in the Nevada desert in 1952.