1996

Life on Mars?

The idea of Mars as a potential abode of life was popularized in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by telescopic observers such as the American businessman and astronomer Percival Lowell, who claimed to see evidence for vast networks of linear canals crisscrossing the parched Martian plains. The media picked up on the notion, exploiting the idea of Martian inhabitants through fantastic (and highly rated) science fiction stories such as the 1938 radio adaptation of H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds.

The search for evidence of life on Mars permeated much of twentieth-century exploration of the Red Planet as well, culminating in the design and operation of a number of highly sensitive organic and biologic detection experiments on the two NASA Viking landers in 1976. While the results of those experiments are widely considered to have been negative (there was no evidence for organic molecules at either landing site, even at the parts-per-billion level), it’s not clear that the uppermost sampled surface materials, which have been exposed to harsh solar UV radiation for perhaps billions of years, should contain any organic molecules. The experiments were limited.

It was against that backdrop that in 1996 a team of NASA scientists studying samples from a meteorite called ALH84001, which was blasted off Mars and eventually fell in Antarctica, made an extraordinary claim. Inside that piece of ancient Martian rock, they claimed, was chemical, mineral, and geologic evidence for fossilized microbes—there had been life on Mars.

The astronomer Carl Sagan was fond of saying that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. In the case of ALH84001, most of the scientific community does not believe that the evidence in support of life is extraordinary—rather, there are nonbiologic explanations for each of the pieces of evidence presented by the NASA researchers. Still, the original team remains convinced. Ultimately, though, it may not matter whether there is convincing evidence of life inside ALH84001. More important may be the fact that most scientists agree that the requirements for life—liquid water, heat and energy sources, and organic molecules—were all present in the environment when this rock was on Mars. That is, ALH84001 helps us know that it was at least habitable.

SEE ALSO Mars and Its Canals (1906), SETI (1960), Vikings on Mars (1976), Cosmos: A Personal Voyage (1980).

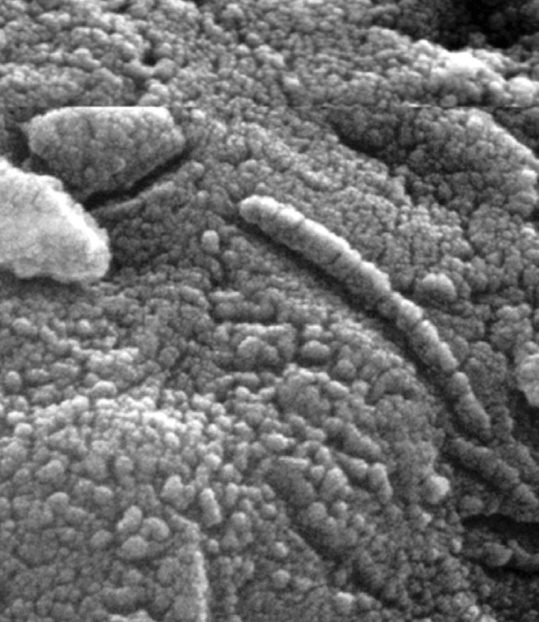

High-resolution scanning electron micrograph image of segmented, tubelike structures—fossilized microbes?—in a chip from the Martian meteorite ALH84001. The longest structure here is only about 100 nanometers wide, or about 1⁄1000th the width of a human hair and half the size of the smallest known living cells on Earth.